Abstract

Trimethylation of histone H3K36 is a chromatin mark associated with active gene expression, which has been implicated in coupling transcription with mRNA splicing and DNA damage response. SETD2 is a major H3K36 trimethyltransferase, which has been implicated as a tumor suppressor in mammals. Here, we report the regulation of SETD2 protein stability by the proteasome system, and the identification of SPOP, a key subunit of the CUL3 ubiquitin E3 ligase complex, as a SETD2-interacting protein. We demonstrate that SPOP is critically involved in SETD2 stability control and that the SPOP/CUL3 complex is responsible for SETD2 polyubiquitination both in vivo and in vitro. ChIP-Seq analysis and biochemical experiments demonstrate that modulation of SPOP expression confers differential H3K36me3 on SETD2 target genes, and induce H3K36me3-coupled alternative splicing events. Together, these findings establish a functional connection between oncogenic SPOP and tumor suppressive SETD2 in the dynamic regulation of gene expression on chromatin.

INTRODUCTION

The methylation of lysine 36 of histone H3 (H3K36) is one of the most conserved epigenetic modification events across species. In S. cerevisiae, H3K36 di- and trimethylation are usually localized within the transcribed regions of active genes. Such modification appears to help stabilize the genome by inhibiting nucleosome exchange and preventing cryptic transcription via the recruitment of histone deacetylase Rpd3 (1–3). Set2 is the sole enzyme for catalyzing all three methyl forms of H3K36 in yeast. It has been shown to interact with RNA polymerase II through its C terminal Set2-Rpb1 interacting (SRI) domain to mediate Pol II recruitment to chromatin (4). The disruption of the interaction leads to Set2 destabilization (5).

Unlike yeast, multiple enzymes have been reported to have the capacity to methylate H3K36 in mammals, including SET domain containing 2 (SETD2), nuclear receptor binding SET domain protein 1, Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome candidate 1 (WHSC1), Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome candidate 1-like 1 (WHSC1L1), PR domain 9 and ash1 (absent, small or homeotic)-like (ASH1L) (1,6–8). Among these, SETD2 is the closest homologue of yeast Set2 and the major enzyme for H3K36 trimethylation in mammalian cells (9,10). The human SETD2 is a large protein of 2564 amino acids, including the conserved C-terminal SRI domain for interaction with RNA Pol II and a SET domain responsible for catalyzing substrate methylation. Interestingly, it also carries a unique uncharacterized N-terminal sequence of over 1400 amino acids, which is not conserved in either Drosophila or yeast.

SETD2-mediated H3K36 trimethylation has been implicated in the regulation of alternative splicing and DNA mismatch repair in mammalian cells (11,12). On several model genes, such as pyruvate kinase isozymes M2 (PKM2), tropomyosin 1 (TPM1) and tropomyosin 2 (TPM2), H3K36 trimethylation appears to influence splice site selection by facilitating the recruitment of MORF-related gene 15 (MRG15) and polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1 (PTB) to chromatin (11). A more recent study identified another histone modification reader, zinc finger, MYND-type containing 11 (ZMYND11, also known as BS69), which selectively recognizes H3.3K36me3 to cause large-scale intron retention (13). In addition, both SETD2 and H3K36 trimethylation have been implicated in DNA damage repair, critical for tumorigenesis (12,14–16). It has unclear whether SETD2-regulated splicing plays role in tumorigenesis.

SETD2 has been reported to be a putative tumor suppressor gene in several cancer types, including clear cell renal carcinoma (CCRC), breast cancer and acute leukemia (17–23). CCRC has been linked to mutations or abnormal expression of an ubiquitin ligase von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL), which is responsible for repressing hypoxia-induced gene expression (17,24). Besides SETD2, several groups have recently identified additional genes mutated or abnormally expressed in CCRC, including lysine (K)-specific demethylase 5C (KDM5C), lysine (K)-specific demethylase 6A (KDM6A), polybromo 1 (PBRM1) and speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) (17–19,25–27). However, it has been unclear how these genes might be functionally connected during tumorigenesis.

Interestingly, SPOP was initially identified as a nuclear protein that exhibits a speckled localization pattern characteristic of splicing factors (28). A more recent study established that SPOP forms an ubiquitin E3 ligase complex with cullin 3 (CUL3) and ring-box 1 (ROC1/RBX1), together poly-ubiquitinating substrates with K48 ubiquitin chains to promote protein degradation via the proteasome pathway (29). The established substrates for SPOP include death-domain associated protein, macro H2A, nuclear receptor coactivator 3 and phosphatase and tensin homolog in mammals, as well as cubitus interruptus in Drosophila (30–35). These findings suggest that SPOP may play a key role in modulating various gene networks during tumorigenesis. Opposite to these oncogenic activities, however, SPOP has also been suggested as a tumor suppressor in prostate cancer (33,36,37), thus implying that SPOP might exert opposite functions in different biological contexts.

In the present study, we connect SPOP to SETD2 by demonstrating SPOP as a specific ubiquitin E3 ligase for this H3K36 methyltransferase, and show that SPOP regulates histone H3K36 trimethylation and alternative splicing through modulating the stability of SETD2 on chromatin. These findings establish a key post-translational mechanism for controlling gene-specific H3K36 trimethylation levels on chromatin, which appears to modulate a variety of chromatin-coupled events during tumorigenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents

HEK293 and 769-P cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and 1x penicillin/streptomycin (HyClone) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Antibodies against Flag-epitope (Sigma), HA-epitope (Sigma), Myc-epitope (Abclonal), EGFP (Abmart), β-Actin (CWBIO), CUL3 (Epitomics) and ROC1 (Epitomics) were purchased from indicated commercial sources. Rabbit anti-SETD2 antibodies were raised and now commercial available at Abclonal. Mouse anti-SPOP antibodies were raised at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, CAS.

Yeast two hybrid screen

cDNA fragments of SETD2 encoding amino acids 504–803 (B1), 804–1103 (B2) and 1104–1403 (B3) were respectively inserted in-frame into the Gal4 DNA-binding domain vector pGBT (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The human HEK293 cell cDNA library (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was screened as described (38). Approximate 1 × 106, 1.2 × 106 and 5 × 105 clones were screened with the above three baits, respectively.

Protein expression in bacteria and GST purification

Individual cDNA sequences were cloned into pGEX-KG vector. The constructs were transformed into BL-21 bacteria, which were induced with 0.2 mM IPTG at 18°C for 4 h. The harvested cells were sonicated and the lysates were centrifuged at 10 000 ×g for 1 h. Recombinant proteins were purified from the supernatant with Glutathione Sepharose 4 according to manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare). Protein concentration was quantified by the Qubit 2.0 (Invitrogen).

Immunoprecipitation

Cultured cells were harvested and lysed in NP40 Lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40) or high salt lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 0.35 M NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5% triton X-100, 1 mM DTT) in the presence of proteinase inhibitors. After removing insoluble particles, the supernatant was incubated with protein G beads (GE Healthcare) and specific antibody at 4°C for 4 h. The beads were spin down and washed three times with lysis buffer. After the final wash, SDS loading buffer was added to the beads to release proteins for SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

GST pulldown assays

GST-SPOP or GST was incubated with glutathione–sepharose beads in binding buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 5% Glycerol, 1% bovine serum albumin) at 4°C for 40 min. The beads were then washed twice with binding buffer, and mixed with HEK293 cell lysate containing wild-type or mutant Flag-tagged SETD2 proteins. Samples were incubated at 4°C for 1 h and followed by washing 3 times with binding buffer. Finally, SDS loading buffer was added and samples were heated to 95°C for 5 min for SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from collected cells with RNA extraction kit (Yuanpinghao) according to manufacturer's instruction. The amount of mRNA was quantified with Qubit (Invitrogen). Approximately 1 µg of total RNA was used for reverse transcription with a first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Toyobo). Real-time PCR was then performed with My-IQ (Biorad) according to the manufacturer's standard protocol. β-actin was used to normalize the amount of each sample. Assays were repeated at least three times. Data shown were average values ± SD. Primer sequences are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Protein expression by baculovirus in insect cells

Proteins was expressed and purified by using Invitrogen BacPAKTM baculovirus expression system. The cDNA sequences of CUL3, ROC1 and SPOP were cloned into pBacPAK9 vector. The SPOP expression vector contains both His and Flag tags at its N terminus. The plasmids were transfected into SF9 cell and viruses were harvested 4 days later. SF9 cells were infected by the viruses and harvested 3 days later. Protein complexes were purified with both Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) and Flag agarose (Sigma).

In vitro ubiquitination assays

The plasmids and purified proteins of E1, E2 and Ub are gifts of Dr Wei Li from Institute of Zoology, CAS. SETD2 fragments were expressed and purified from bacteria. The SPOP/CUL3/ROC1 complex was expressed with the baculovirus expression system and purified from insect cells. In vitro ubiquitination assays were carried out by adding E1(0.2 μg), 6His-UbcH5b(2 μg), GST-HA-SETD2-B3(5 μg), 6His-Ub(5 μg), SPOP-Cul3-ROC1 complex in ubiquitination buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM ATP,10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM DTT) to a final volume of 50 μl. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and stopped with 1% SDS. The samples were heated at 95°C for 5 min and diluted 10-fold in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40,1 mM DTT, 1 mM Aprotinin, 1 mM Leupeptin) for immunoprecipitation or immunoblot analysis.

ChIP assays

ChIP assay was performed as previously described (39). Briefly, approximately 1 × 107 cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde and then quenched with glycine. The cells were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline and then harvested in ChIP lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA). DNA was sonicated to 400–600 bp. After centrifugation, four volumes of ChIP dilution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) were added to the supernatant. The lysate was then incubated with protein G beads and antibodies at 4°C overnight. The beads were washed 5 times and DNA was eluted by Chip elution buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, 1% SDS, 30 μg/ml proteinase K). The eluent was incubated at 65°C overnight and DNA was extracted with DNA purification kit (Sangon). Purified DNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR with Biorad MyIQ. Assays were repeated at least three times, and data shown were average values ± SD.

RNA-Seq and analysis of alternative splicing

A total of 10 μg of RNA mixture was used for mRNA purification and RNA-Seq library preparation. Quality control was evaluated on Agilent 2100 and sequencing was performed on Illumina Hiseq4000 platform with 150 paired end mode. Approximately 90 million reads were generated for each sample, and the data presented were based on two independent RNA-seq experiments.

Quality control for raw sequencing data was performed by FastQC v0.10.1. Low quality reads and adaptor contamination were removed by Cutadapt 1.8.3. After quality control and data filtering, reads were aligned to the reference genome hg19 by TopHat v2.0.10, allowing 2 mismatches per read and only concordant paired end reads were accepted for downstream analysis. MATS.3.0.8 beta and rmats2sashimiplot were used for alternative splicing analysis and related significant splicing events plot. Splicing events were accepted as significant with FDR < 0.05. Functional analysis and Gene Ontology (GO) analysis were performed by DAVID. GO plot R package was used for GO analysis plot and R version 3.2.2 was used for some custom analysis.

ChIP-Seq sequencing and ChIP-Seq data analysis

ChIP-Seq was performed by using Rubicon ThruPLEX DNA-seq kit according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, ChIPed DNA and matched input DNA were prepared for end repair and ‘A’ tailing, adaptor ligation and library amplification. ChIP-Seq sequencing was performed on Illumina HiSeq2500 platform with 50 bp single end sequencing. The data presented were based on two independent experiments.

Quality control was performed with FastQC. CutAdapt was next used to trim low quality bases and adaptor sequences. Bowtie was used for data mapping to the hg19 reference genome, allowing two mismatches. Samtools was used to remove PCR-duplicated reads and only unique mapped reads were kept for downstream analysis. ChIP-Seq peaks calling was performed by MACS with P-value 1e-6. Genes that showed altered H3K36me3 levels were identified after normalizing all data to reads per million. The line plot of ChIP-Seq enrichment was performed by ngs.plot.

Data access

All genomic data were available at the GEO database under the accession number GSE75270.

RESULTS

Regulation of SETD2 protein stability by the proteasome system

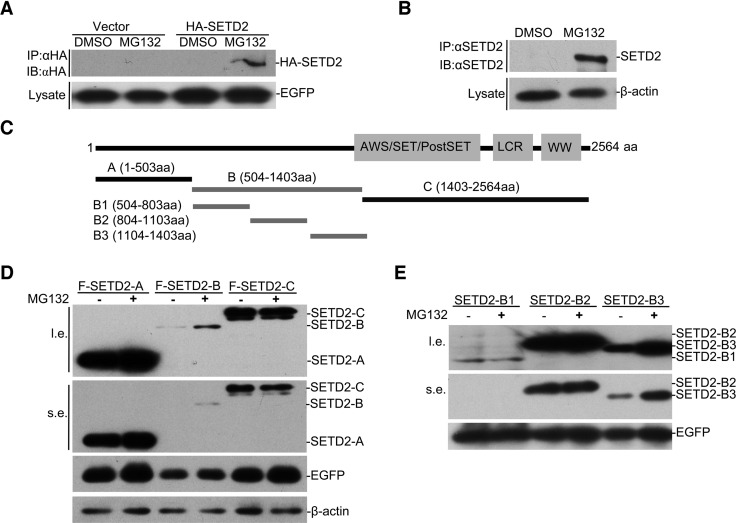

It is well known that SETD2 is expressed at low levels in mammalian cells, which is difficult to detect by Western blot in total cell lysate (12). To determine its contribution to histone H3K36 methylation, we attempted to overexpress FLAG or HA-tagged exogenous SETD2 in HEK293 cells, and to our surprise, we hardly detected the exogenous protein by Western blot with either anti-Flag or anti-HA antibodies, while co-transfected EGFP was well expressed (Figure 1A). Both endogenous and exogenous SETD2 mRNAs were readily detectable (data not shown), implying that the SETD2 protein might be subjected to stringent translational and/or post-translational control in the cell. To test this hypothesis, we treated the cell with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, finding that the treatment significantly increased the levels of both endogenous and exogenous SETD2 (Figure 1A and B). These data strongly suggest that SETD2 is tightly regulated at the protein stability level by the proteasome system.

Figure 1.

SPOP regulates SETD2 stability in a proteasome-dependent manner. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-SETD2 or empty vector followed by DMSO or MG132 (10 μM) treatment. EGFP was co-transfected as control. HA immunoprecipitation and Western blot were carried out. (B) HEK293 cells were treated with DMSO or MG132 (10 μM) for 12 h. Endogenous SETD2 was immunoprecipitated and blotted with antibody against SETD2. β-actin served as control. (C) Schematic representation of SETD2 deletion mutants tagged with FLAG or HA. (D and E) Identification of the E3 ligase target region of SETD2. HEK293 cells were transfected with different Flag-tagged truncations of SETD2 for 48 h and then treated with or without MG132 (10 μM) for 12 h. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot (IB) with anti-FLAG antibody.

To localize the region(s) in SETD2 responsible for proteasome-mediated degradation, we separately expressed a series of SETD2 segments (Figure 1C). We found that both fragment A and C were well expressed and neither exhibited obvious change in response to MG132 treatment. In contrast, fragment B was poorly expressed and sensitive to MG132 (Figure 1D), suggesting that this segment contains a signal for protein degradation. By further dissecting this fragment, we found that fragment B1 was poor expressed but not proteasome-dependent, while B3 showed selective sensitivity to MG132 (Figure 1E). These observations indicate that the B segment harbors two distinct signals for regulating SETD2 expression at the protein level, and B3 fragment accounts for post-translational degradation by the proteasome.

Identification of SPOP as a SETD2-interacting protein

We first chose to focus on the mechanism underlying the regulation of SETD2 protein stability by carrying out a yeast two-hybrid screen to identify SETD2-interacting proteins. Using B3 as a bait, we identified several candidate SETD2-interacting proteins, one of which corresponds to most of the amino acid residues of SPOP, a ubiquitin E3 ligase previously established to be part of the complex with CUL3 and ROC1 (29).

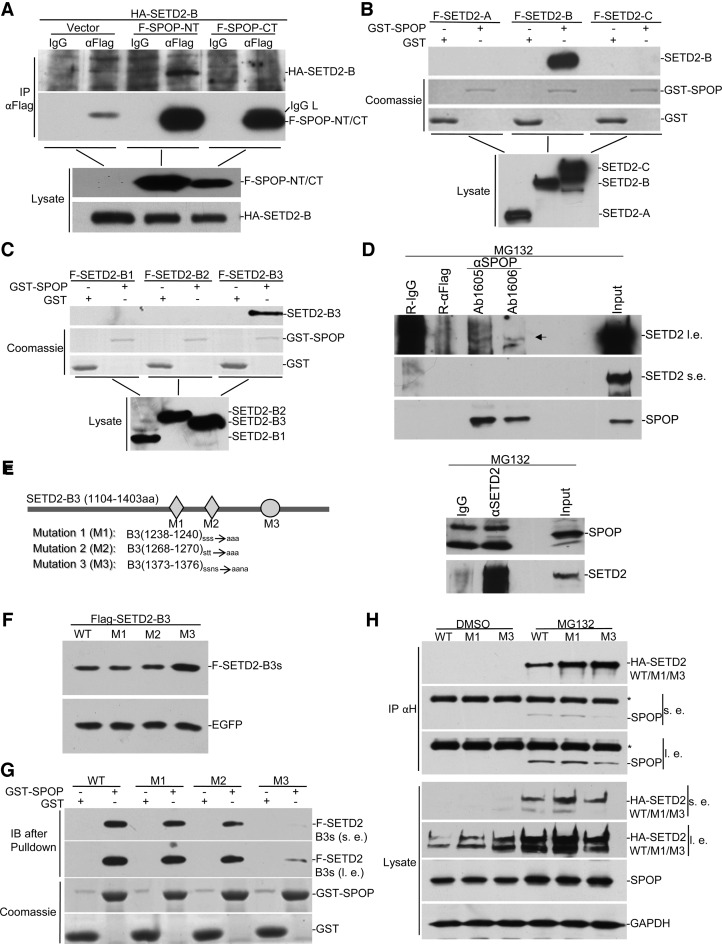

To confirm the interaction between SPOP and SETD2, we performed co-immunoprecipitation and GST-pulldown assays. Previous experiments indicated that the C-terminal BTB domain in SPOP interacts with CUL3, and its N-terminal MACH domain is responsible for substrate recognition (29). We thus tested the prediction that SETD2 might directly interact with the MACH domain of SPOP by co-expressing SETD2-B with either the N- or C-terminal fragment of SPOP in HEK293 cells, finding that SETD2 indeed interacted with the N-, but not C-terminal, portion of SPOP (Figure 2A). The GST pulldown assay further confirmed the direct interaction of bacterially expressed SPOP with both SETD2-B and B3 fragments (Figure 2B and C). The full-length SETD2 protein is difficult to detect in the cell, thus preventing verification of its interaction with SPOP under standard conditions; however, the presence of MG132, we detected the interaction between the endogenous SETD2 and SPOP (Figure 2D). Because of strong background with rabbit IgG at the size of SETD2, we utilized rabbit anti-Flag as negative control in this analysis (Figure 2D upper). Two different anti-SPOP antibodies both pulled down SETD2 (Figure 2D upper), and endogenous SETD2 also pulled down SPOP (Figure 2D bottom). Despite relatively weak signals, the results clearly showed the interaction between endogenous SETD2 and SPOP.

Figure 2.

SPOP interacts with SETD2. (A) HA-SETD2-B. was transfected into HEK293 with FLAG-SPOP-NT or FLAG-SPOP-CT. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG, followed by anti-HA Western blot. (B and C) SETD2 domains were mapped for SPOP binding by GST pulldown. GST-SPOP was expressed and purified from bacteria. FLAG-tagged different fragments of SETD2 were expressed in HEK293 and lysates were subject to GST pulldown assays. (D) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous SETD2 and SPOP. HEK293 cell were treated with MG132 and co-immunoprecipitation was carried out with SETD2 antibody and two different SPOP antibodies, as indicated. (E) Schematic representation of mutations of predicted SPOP binding sites. (F) HEK293 cells were transfected with equal amounts of EGFP and FLAG-tagged SETD2-B3 mutants. Lysates were assayed by Western blot. (G) The wild type and mutants of SETD2-B3 fragment were subjected to GST-pulldown as in B and C. SPOP pulled down less M3 compared with wild type and other mutants. (H) The wild type and the M1 and M3 versions of full-length SETD2 were respectively expressed in HEK293 cells together with FLAG-SPOP. *indicates IgG heavy chain, s.e. for short exposure, and l. e. for long exposure.

Previous structural analysis of SPOP substrates revealed the involvement of a conserved motif for interaction with the MACH domain (29). We surveyed for such motif in SETD2 and identified three putative SPOP binding sites in the B3 segment. We mutated the essential serine or threonine to alanine in each site (Figure 2E) and tested the effect of each mutant on increasing the stability of SETD2 in transfected HEK293 cells. We found that only mutant M3 became more stable compared to its wild type counterpart (Figure 2F). We also used the GST pulldown assay to determine the impact of each mutant on the interaction with SPOP, finding again that the M3 mutant bound much less efficiently with GST-SPOP, while all other three mutants showed no obvious difference (Figure 2G). We detected the interaction of full-length SETD2 with SPOP in the presence of MG132, which was only impaired by M3 mutation (Figure 2H).

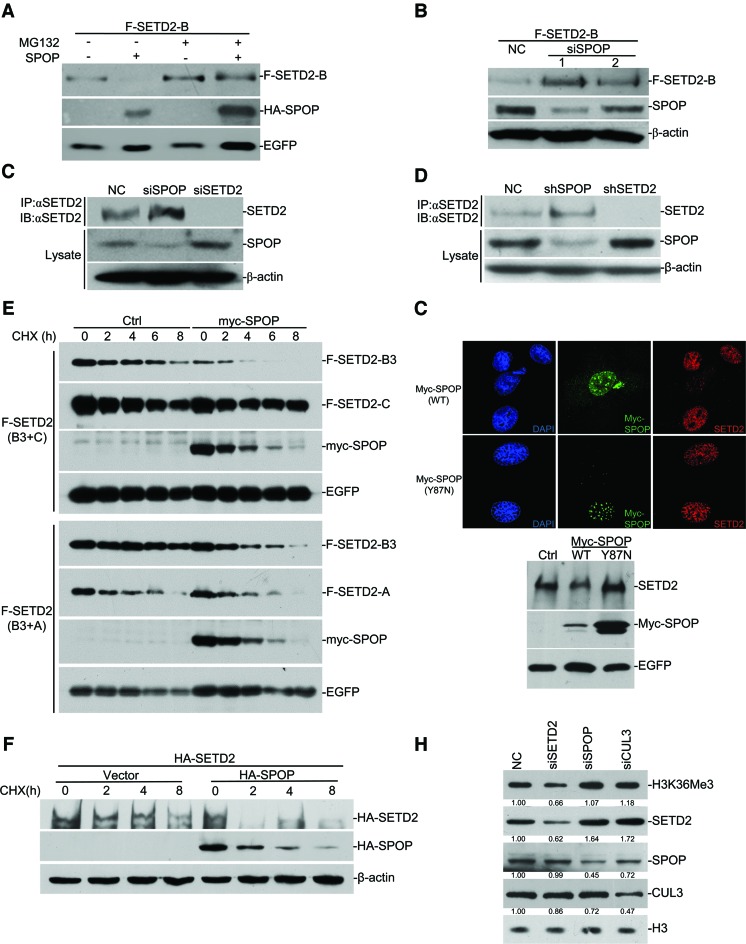

Control of SETD2 stability by SPOP

Having established SPOP as a SETD2-interacting protein, we next tested the possibility that the SPOP/CUL3/ROC1 complex functions as an E3 ligase for SETD2. We first co-transfected SETD2-B with SPOP in HEK293 cells, finding that SETD2-B protein level decreased upon SPOP overexpression and the effect could be prevented by MG132 (Figure 3A). Conversely, knockdown of SPOP with two independent siRNAs increased the SETD2-B protein level in transfected HEK293 cells (Figure 3B). We made similar observations on the endogenous SETD2, by either transient knockdown of SPOP with siRNA (Figure 3C) or stable knockdown of SPOP using shRNA (Figure 3D). Cells transfected with Flag-SETD2-B3 and HA-SPOP were treated with cycloheximide to measure the protein decay rate and SETD2 fragment A or C was tested as control. The results indicated SETD2-B3 fragment was degraded faster in response to overexpressed SPOP, while SETD2-A or -C had no difference with or without SPOP (Figure 3E). Co-expression of HA-SPOP also significantly increased the decay rate of HA-tagged full-length SETD2 (Figure 3F). Immunofluorescent staining indicated that the exogenous expressed SPOP has a speckle-like distribution, which was probably related nuclear speckle as reported previously (28). Expression of wild-type SPOP greatly decreased the endogenous SETD2 in the cell, but not SPOP Y87N (36), a dead ligase mutant (Figure 3G). CUL3 is one of core subunits for the SPOP E3 ligase complex. As expected, its depletion increased SETD2 and H3K36me3 levels in the cell (Figure 3H). These data suggest that SPOP controls SETD2 stability, likely acting as part of the E3 ligase for SETD2 in mammalian cells.

Figure 3.

SPOP regulates SETD2 stability. (A) FLAG-SETD2-B. was expressed in HEK293 cells with or without HA-SPOP for 48 h. MG132 (10 μM) was added as indicated. Lysates were subjected to Western blot with indicated antibodies. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with siRNAs against SPOP or negative control siRNA (NC) for 12 h, followed by FLAG-SETD2-B transfection. Lysates were assayed with Western blot as indicated. (C) HEK293 cells were transfected with NC, SPOP or SETD2 siRNA for 72 h. Lysates were immunoprecipitated and assayed with western as indicated. (D) Lysates of stable cell lines containing SETD2, SPOP or control shRNA were assayed by Western blot with the antibodies as indicated. (E) FLAG-SETD2-B3 and MYC-SPOP were co-expressed in HEK293 cells, together with FLAG-SETD2-C (upper) or FLAG-SETD2-A (bottom). Western blotting was performed after cycloheximide (CHX) treatment with indicated time. (F) HA-tagged SETD2 full-length protein was expressed in HEK293 cells with or without HA-SPOP. The cells were then treated with CHX and blotted as indicated. (G) Wild type or Y87N enzymatic dead mutant SPOP was expressed and endogenous SETD2 was assayed by immunofluorescent staining and Western blot. (H) SPOP, CUL3 and SETD2 were knocked down by siRNA, and the total H3K36me3 levels were measured by Western blot. The numbers under the figure represent the relative protein fold change compared with NC.

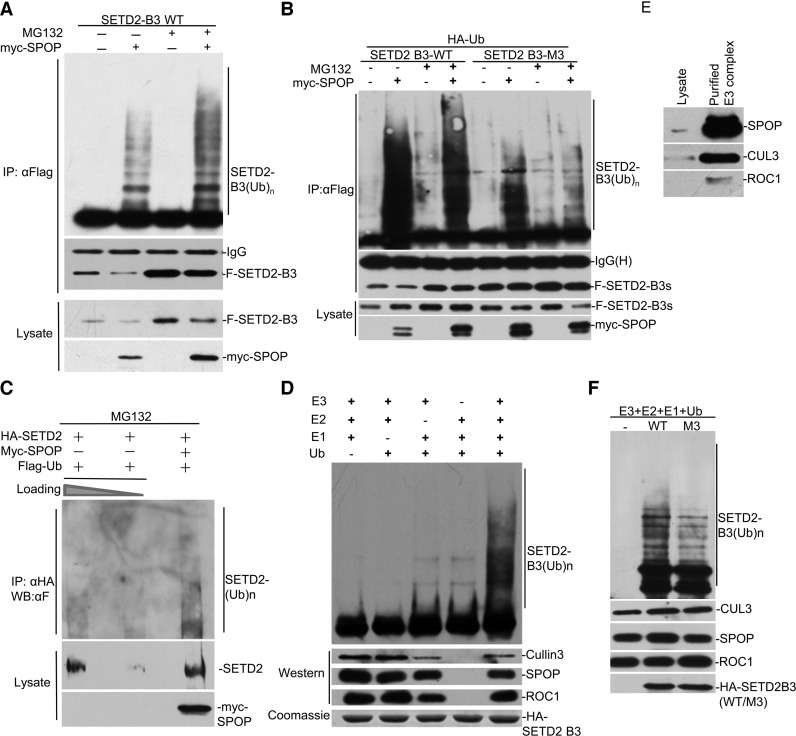

SETD2 poly-ubiquitination catalyzed by SPOP/CUL3/ROC1 complex

To determine whether SPOP has the capacity to ubiquitinate SETD2, we performed in vivo and in vitro ubiquitination assays. Because the molecular weight of full-length SETD2 is close to 300 kD, which tends to obscure the resolution of ubiquitinated bands on SDS-PAGE, we performed ubiquitination assays on the SETD2-B3 segment instead. We expressed FLAG-SETD2-B3 and HA-ubiquitin in HEK293 cells with or without co-expressing Myc-tagged SPOP. The lysate was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG followed by Western blotting analysis with anti-HA antibody. We found that co-expression with SPOP significantly increased poly-ubiquitination of SETD2-B3 and MG132 further enhanced the extent of poly-ubiquitination (Figure 4A). As expected, the SPOP binding-deficient mutant M3 significantly attenuated the poly-ubiquitination reaction (Figure 4B). We also successfully observed the increased signal of SETD2 poly-ubiquitination with SPOP co-expression (Figure 4C). We further tested whether SPOP-mediated ubiquitination of SETD2 was dependent on lysine 48 or 63 of ubiquitin by replacing wild-type ubiquitin with either the K48 only or the K63 only form. The results showed that SPOP exclusively promoted poly-ubiquitination at the K48 site (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 4.

SPOP complex ubiquitinates SETD2 in vivo and in vitro. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with MYC-SPOP, HA-ubiquitin, FLAG-SETD2-B3 as indicated, followed by MG132 treatment for 12 h. Lysates were immunoprecipitated and Western blotted as indicated. The shifted smear corresponded to poly-ubiquitinated SETD2. (B) FLAG-SETD2-B3 or FLAG-SETD2-B3 (M3) was subjected for ubiquitination assay as in (E). (C) In vivo ubiquitination assay was carried out with HA-tagged full-length SETD2 in the cell. The lysate without SPOP was loaded into the left two lanes with different amounts. (D and E) His-Flag-SPOP, ROC1 and CUL3 were co-expressed by baculovirus and purified as described in the Experimental Procedures. Purified SPOP/CUL/ROC1 complex was incubated with or without E1, E2 and Ub. (F) Purified wild-type SETD2-B3 and the M3 mutant were tested as substrates, respectively, and in vitro ubiqutination assay was carried out as (G).

To demonstrate that the SPOP/CUL3/ROC1 complex is able to directly ubiquitinate SETD2, we expressed SPOP/CUL3/ROC1 by baculovirus in insect cells and purified the complex by tandem affinity chromatography via the FLAG and His tag (Figure 4D and E, see Materials and Methods). We next used this purified complex to perform in vitro ubiquitination assay using bacterially expressed SETD2-B3 as a substrate. In the presence of E1, E2 and ubiquitin, the SPOP/CUL3/ROC1 complex was highly active in poly-ubiquitinating SETD2-B3 in vitro (Figure 4D). The M3 mutant showed much less ubiquitination in vitro relative to the wild-type protein (Figure 4F). These data strongly suggest that the SPOP/CUL3/ROC1 complex is a bona fide ubiquitin E3 ligase for SETD2.

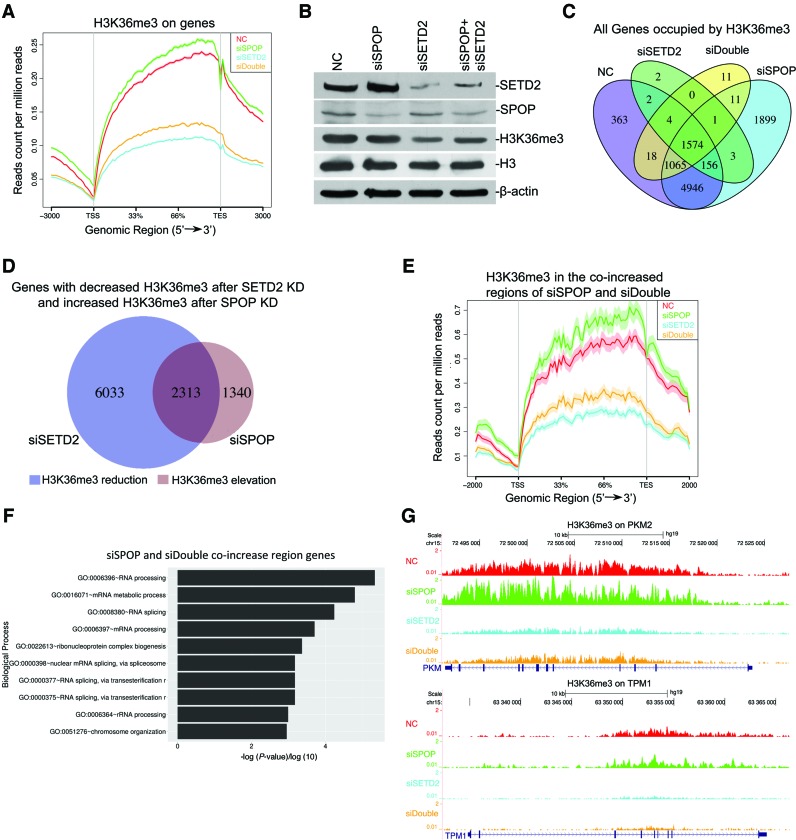

SPOP-regulated histone H3K36 trimethylation

Having established the E3 ligase function of SPOP for SETD2, we then determined how this system might contribute to the regulation of H3K36me3. We perform H3K36me3 ChIP-seq before and after knocking down SPOP and SETD2, either alone or in combination. Based on two independent ChIP-seq experiments, which established the reproducibility of the data (Supplementary Figure S2A), we validated the main genomic distribution of H3K36me3 on introns, as reported earlier (Supplementary Figure S2B) (40). Significantly, global analysis showed that SPOP knockdown increased H3K36me3, while SETD2 knockdown dramatically reduced this modification, which largely cancelled the effect of SPOP knockdown (Figure 5A and B). We calculated the numbers of genes occupied by H3K36me3 in the four samples, finding that SETD2 knockdown decreased H3K36me3 on ∼80% of genes, which is consistent with the previous report that SETD2 is a major H3K36me3 methyltransferase in the cell (Figure 5C) (10). The genes that showed elevated H3K36me3 after SPOP knockdown were largely overlapped with those with down-regulated H3K36me3 after SETD2 knockdown (Figure 5D). Interestingly, the overlapped genes from our analysis are enriched with cell cycle and transcription regulation, implicating their potential roles in cancers induced by SPOP and/or SETD2 (Supplementary Figure S2C). We conclude from these data that SPOP negatively regulates H3K36me3 by modulating SETD2 stability.

Figure 5.

Genome-wide analysis of H3K36me3 regulated by SPOP. (A) SPOP and SETD2 were knocked down by specific siRNAs separately or together in HEK293 cells. Line plot shows H3K36me3 enrichment levels in the gene body under different conditions. (B) SPOP and SETD2 were knocked down by siRNA separately or together and Western blotting was carried out to monitor knockdown efficiency. (C) H3K36me3 enrichment on the whole body of each gene locus was calculated after RPM (read per million) normalized. Venn diagram shows various overlaps of genes occupied by H3K36me3 in the cells described in (A). (D) Venn diagram shows the comparison between genes showing down-regulated H3K36me3 after SETD2 knockdown and those showing up-regulated H3K36me3 after SPOP knockdown. (E) Genes with H3K36me3 elevation both in SPOP knockdown versus control and co-knockdown versus SETD2 knockdown were selected with the Line plot showing H3K36me3 levels on their gene bodies. (F) Gene Ontology analysis shows the enriched biological processes of the genes in (F). (G) Landscape of H3K36me3 distribution on PKM and TPM1.

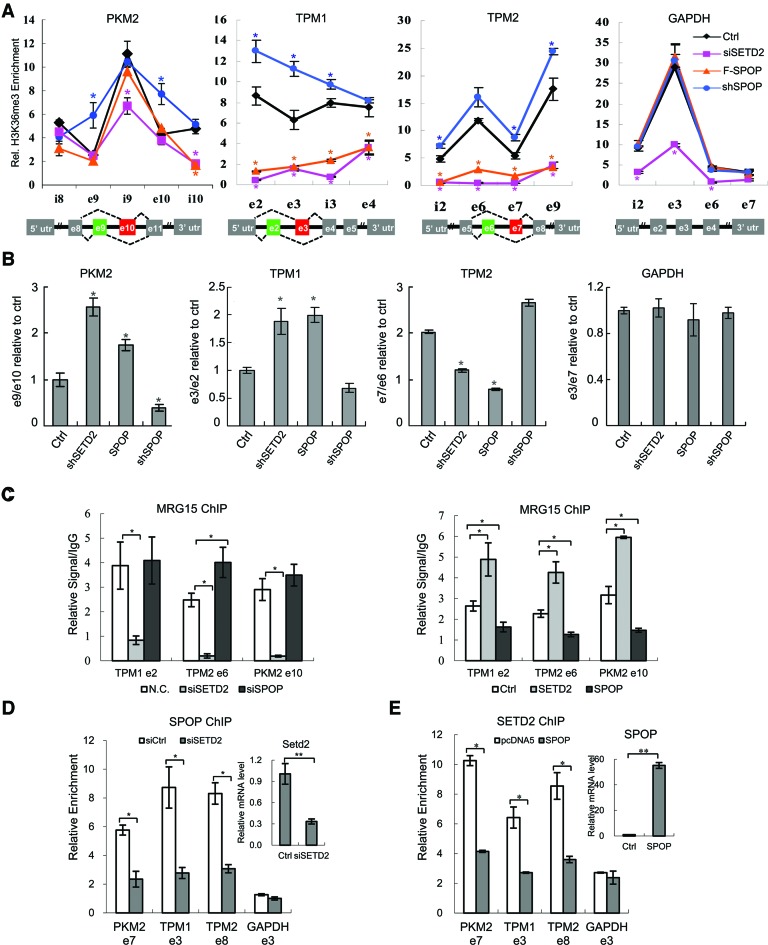

H3K36me3-coupled mRNA alternative splicing

Our ChIP-Seq data indicated that H3K36me3 on a large number of genes responded to SPOP and SETD2 knockdowns in opposite directions (Figure 5D). We therefore selected the genes that showed H3K36me3 up regulation in both SPOP knockdown and SPOP/SETD2 double knockdown cells, (Figure 5E and Supplementary Figure S2D), which likely correspond to the genes sensitive to SPOP-regulated SETD2 degradation. Interestingly, GO analysis of these genes revealed that they are enriched in biological processes related to RNA processing and splicing (Figure 5F). In light of a previous study on H3K36me3 regulated splicing on PKM2, TPM1 and TPM2 (11), we examined and found that H3K36me3 on these model genes were indeed regulated by SPOP (Figure 5G). By ChIP-qPCR, we confirmed that SETD2 knockdown and SPOP overexpression significantly reduced, while SPOP knockdown increased, H3K36me3 levels on these genes (Figure 6A). In contrast, while SETD2 knockdown decreased H3K36me3 on the GAPDH gene, neither SPOP knockdown nor overexpression showed detectable effect (Figure 6A). To further confirm the regulation of these genes by both SETD2 and SPOP, we double-knocked down SETD2 and SPOP and found that H3K36me3 levels on PKM2 and TPM2 were restored to control levels (Supplementary Figure S3A).

Figure 6.

SPOP modulates H3K36me3 on SETD2 target genes. (A) ChIP analysis of H3K36me3 on PKM2, TPM1, TPM2 and GAPDH genes in SETD2 shRNA, SPOP shRNA and SPOP overexpression stable cell lines. Y-axis represents relative signals of H3K36me3 over H3. (B) Specific primers were designed to detect the indicated exons of PKM2, TPM1 and TPM2, as reported (11), and individual alternative splicing events were measured by quantitative PCR and represented by the ratios of different exons. GAPDH was used as control. (C) ChIP analysis of MRG15 on TPM1, TPM2 and PKM2 genes under indicated conditions. Y-axis represents relative MRG15 signals over IgG control. (D) ChIP analysis of SPOP on PKM2, TPM1, TPM2 and GAPDH genes in SETD2 knockdown cells. Y-axis represents relative SPOP signals over IgG control. (E) ChIP analysis of SETD2 on PKM2, TPM1, TPM2 and GAPDH genes in SPOP overexpression cells. Y-axis represents relative SETD2 signals over IgG control. *P-value < 0.05; **P-value < 0.01. n = 3.

We next examined alternative splicing of these genes by semi-quantitative PCR and found that SETD2 knockdown induced splicing in PKM2, TPM1 and TPM2 (Figure 6B). Consistent with its role in regulating SETD2 stability, SPOP overexpression caused similar changes to those induced by SETD2 knockdown, and SPOP knockdown altered splicing of these genes in the opposite direction (Figure 6B). The double knockdown of SETD2 and SPOP rescued the phenotype caused by deficiency of single genes (Supplementary Figure S3B). MRG15 was previously shown to bind H3K36me3 and modulate alternative splicing (11). ChIP-qPCR analysis with MRG15 antibody showed that SPOP knockdown increased chromatin-bound MRG15 on these genes while overexpression caused the opposite effects (Figure 6C). Together, these data strongly suggest a role of SPOP in H3K36me3-regulated alternative splicing by modulating SETD2 stability.

Interaction of SPOP with chromatin to locally regulate SETD2 stability

To pursue the mechanism for the selective effect of SPOP on SETD2 target genes, we hypothesized that SPOP might have its own targeting specificity on chromatin. We tested this hypothesis by performing ChIP-qPCR on a panel of SETD2 sensitive genes that were differentially modulated by SPOP. We first examined our home-made anti-SPOP antibodies to assure their suitability for ChIP assays (Supplementary Figure S3C and S3D) and found that SPOP bound strongly on PKM2, TPM1 and TPM2, but near the background level on GAPDH, and importantly, SETD2 knockdown reduced SPOP binding on all three target genes (Figure 6D). We performed a converse experiment with anti-SETD2, finding that SETD2 bound all four target genes examined, and SPOP overexpression reduced SETD2 binding on PKM2, TPM1 and TPM2, but not on GAPDH (Figure 6E). Together, these findings suggest that SPOP may be associated with chromatin through its interaction with SETD2 rather than direct binding. In contrast, SETD2 could clearly bind to other target genes in the absence of SPOP, which provides a reasonable account for SPOP-modulated H3K36me3 on only a subset of SETD2 target genes.

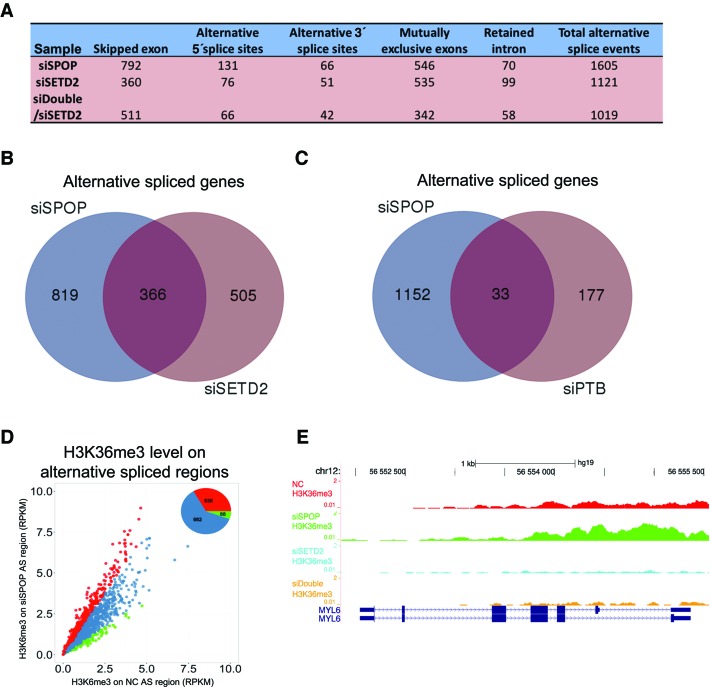

Transcriptome analysis revealed alternative splicing regulated by SPOP

We performed RNA-Seq to further illustrate the regulatory functions of SPOP and SETD2 in alternative splicing. Over 1000 altered splicing events were detected in each sample (Figure 7A, and Supplementary Table S2–S4), some of which were verified by RT-PCR (Supplementary Figure S4A–E), and a large number of alternative spliced genes in SPOP and SETD2 knockdown were overlapped (Figure 7B). We also compared our data with those from a published study (41), noting ∼20% of SPOP-regulated genes were also regulated by PTB (Figure 7C), suggesting these genes are co-regulated by SPOP and PTB. We also analyzed 24 genes implicated in RNA processing identified in Figure 5G and found that 8 of them showed induced alternative splicing in response to SPOP knockdown (Supplementary Figure S4F), indicating that SPOP may regulate splicing through modulating alternative splicing of splicing regulators.

Figure 7.

Transcriptome regulated by SPOP and SETD2. (A) Alternative splicing events regulated by SPOP and SETD2 in HEK293 cells. (B) Venn diagram shows overlapped alternative splicing events in response to SPOP and SETD2 knockdown. (C) Venn diagram shows overlapped alternative splicing events regulated by SPOP and PTB. (D) The Scatterplot shows the H3K36me3 levels on alternative spliced sites in SPOP knockdown and control cells. Compared to blue-labeled sites, red represent the sites with higher H3K36me3 in SPOP knockdown cells and green dots for the sites with lower H3K36me3. (E) H3K36me3 levels on MYL6, a typical alternative spliced gene identified in RNA-Seq analysis.

To further strengthen the relationship between alternative splicing and H3K36me3 regulated by SPOP, we analyzed the H3K36me3 levels around the alternative spliced sites, and found that one-third of these sites (535 of 1605 sites) contained higher H3K36me3 in the cells after SPOP depletion, in comparison with the control, while only ∼5% (88 of 1605 sites) had lower signals (Figure 7D). This is illustrated on an exemplary gene on which SPOP or SETD2 knockdown enhanced or reduced H3K36me3 (Figure 7E), which was correlated to altered splicing, as verified by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Supplementary Figure S4B and S4D). These data suggest that SPOP may function via modulating SETD2 stability to globally regulate alternative splicing in mammalian cells.

DISCUSSION

We report the SPOP/CUL3/ROC1 complex as an ubiquitin E3 ligase for SETD2, a key enzyme in epigenetic regulation. We provide evidence that SPOP directly interacts with SETD2, thereby regulating SETD2 activities on a large subset of genes. This pathway is particularly pertinent to regulated splicing via modulating the H3K36me3 levels in the cell, and our data provide additional support to the involvement of MRG15 and PTB in chromatin-coupled splicing, which has been shown as one splicing repressor and mainly regulates mutually exclusive exons (11,41). Our analysis suggests that the events regulated by SETD2 and SPOP include many alternative splicing types, but mainly exon exclusion (Figure 7A), which supports the role of PTB in alternative splicing regulated by SPOP and SETD2. A more recent study revealed another H3K36me3 reader, BS69/ZMYND11, responsible for various exon skipping and intron retention events detected (13). It will be interesting in future studies to determine how SPOP might be involved in alternative splicing regulated by BS69/ZMYND11 or other potential H3K36me3 readers.

An early study showed that disruption of the interaction between Set2 and RNA Pol II leads to Set2 destabilization in yeast (5). Because the fragment recognized by SPOP uncovered in our study is not conserved in yeast, the mechanism described here is likely limited to higher eukaryotes.

Our Western blotting results suggest that SPOP knockdown elevated ∼10% of H3K36me3 in the cell (Figure 5C), while the immunostaining result show that SPOP overexpression had a dramatic effect on SETD2 (Figure 3F). These likely reflect incomplete SPOP knockdown by siRNA and the dominant effect of overexpressed SPOP, although it is also possible that endogenous SPOP may selectively regulates a subset of SETD2 target genes. Considering the localization of SPOP in nuclear speckles (28), we speculate that SPOP may preferentially regulate SETD2 stability on chromatin with spatial proximity to nuclear speckles.

Our findings also have important implications in the biological functions of both SPOP and SETD2, as both have been suggested to play critical roles in CCRC, where SPOP was proposed to function as an oncogene whereas SETD2 as a tumor suppressor (27,35). Because their functions are now converged on regulated H3K36 trimethylation and chromatin-coupled alternative splicing, our findings provide a new angle to understand how defects in SPOP and SETD2 may contribute to kidney cancer. Interestingly, SPOP has been suggested to have an oncogenic function in CCRC, but a tumor suppressive role in prostate cancer (27,33,35–37,42). It is possible that SPOP, besides negatively regulating H3K36me3 levels, may have distinct specificity on other substrates in different cancers. It will be interesting to test this hypothesis by comparing the function of SPOP in these two tumor models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Wei Li of Institute of Zoology, CAS, for sharing purified E1, E2 and ubiquitin used in ubiquitination assays, and Dr Man Mohan of Shanghai Jiaotong University for manuscript editing and discussion.

This work was supported by grants from National Key Research and Development Plan of China (2016YFA0502100), National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, 2012CB518700 and 2011CB504206), National Natural Science Foundation of China to M.W. (31470771 and 31521091) and L.L. (31200653 and 31370866). The authors also acknowlede the support of the 973 programs (2011CB811300 and 2012CB910800) to X.D.F.

Author contributions: K.Z., L.G.J. and X.W. performed most of the experiments; P.J.L. prepared samples for high throughput sequencing and analyzed the data; K.H. performed the yeast two hybrid screen and identified and characterized SPOP; Y.Z. contributed to some experiments; B.Y., C.S. and G.W. helped sequencing and bioinformatics analysis of data, M.W. directed the project and wrote the manuscript. X.D.F., L.L. and M.W. discussed and edited the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Key Research and Development Plan of China [2016YFA0502100]; National Basic Research Program of China [973 Program, 2012CB518700 and 2011CB504206]; National Natural Science Foundation of China to Min Wu [31470771 and 31521091] and Lianyun Li [31200653 and 31370866]; 973 programs [2011CB811300 and 2012CB910800 to X.D.F.]. Funding for open access charge: National Natural Science Foundation of China [31470771 and 31521091]; National Basic Research Program of China [973 Program, 2012CB518700].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wagner E.J., Carpenter P.B. Understanding the language of Lys36 methylation at histone H3. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:115–126. doi: 10.1038/nrm3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venkatesh S., Smolle M., Li H., Gogol M.M., Saint M., Kumar S., Natarajan K., Workman J.L. Set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 suppresses histone exchange on transcribed genes. Nature. 2012;489:452–455. doi: 10.1038/nature11326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keogh M.C., Kurdistani S.K., Morris S.A., Ahn S.H., Podolny V., Collins S.R., Schuldiner M., Chin K., Punna T., Thompson N.J., et al. Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell. 2005;123:593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kizer K.O., Phatnani H.P., Shibata Y., Hall H., Greenleaf A.L., Strahl B.D. A novel domain in Set2 mediates RNA polymerase II interaction and couples histone H3 K36 methylation with transcript elongation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:3305–3316. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3305-3316.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs S.M., Kizer K.O., Braberg H., Krogan N.J., Strahl B.D. RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain phosphorylation regulates protein stability of the Set2 methyltransferase and histone H3 di- and trimethylation at lysine 36. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:3249–3256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.273953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman S., Sowa M.E., Ottinger M., Smith J.A., Shi Y., Harper J.W., Howley P.M. The Brd4 extraterminal domain confers transcription activation independent of pTEFb by recruiting multiple proteins, including NSD3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:2641–2652. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01341-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y., Trojer P., Xu C.F., Cheung P., Kuo A., Drury W.J., 3rd, Qiao Q., Neubert T.A., Xu R.M., Gozani O, et al. The target of the NSD family of histone lysine methyltransferases depends on the nature of the substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:34283–34295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.034462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eram M.S., Bustos S.P., Lima-Fernandes E., Siarheyeva A., Senisterra G., Hajian T., Chau I., Duan S., Wu H., Dombrovski L., et al. Trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 36 by human methyltransferase PRDM9 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:12177–12188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.523183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoh S.M., Lucas J.S., Jones K.A. The Iws1:Spt6:CTD complex controls cotranscriptional mRNA biosynthesis and HYPB/Setd2-mediated histone H3K36 methylation. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3422–3434. doi: 10.1101/gad.1720008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edmunds J.W., Mahadevan L.C., Clayton A.L. Dynamic histone H3 methylation during gene induction: HYPB/Setd2 mediates all H3K36 trimethylation. EMBO J. 2008;27:406–420. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luco R.F., Pan Q., Tominaga K., Blencowe B.J., Pereira-Smith O.M., Misteli T. Regulation of alternative splicing by histone modifications. Science. 2010;327:996–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1184208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li F., Mao G., Tong D., Huang J., Gu L., Yang W., Li G.M. The histone mark H3K36me3 regulates human DNA mismatch repair through its interaction with MutSalpha. Cell. 2013;153:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo R., Zheng L., Park J.W., Lv R., Chen H., Jiao F., Xu W., Mu S., Wen H., Qiu J., et al. BS69/ZMYND11 reads and connects histone H3.3 lysine 36 trimethylation-decorated chromatin to regulated pre-mRNA processing. Mol. Cell. 2014;56:298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfister S.X., Ahrabi S., Zalmas L.P., Sarkar S., Aymard F., Bachrati C.Z., Helleday T., Legube G., La Thangue N.B., Porter A.C., et al. SETD2-dependent histone H3K36 trimethylation is required for homologous recombination repair and genome stability. Cell Rep. 2014;7:2006–2018. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carvalho S., Vitor A.C., Sridhara S.C., Martins F.B., Raposo A.C., Desterro J.M., Ferreira J., de Almeida S.F. SETD2 is required for DNA double-strand break repair and activation of the p53-mediated checkpoint. eLife. 2014:e02482. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aymard F., Bugler B., Schmidt C.K., Guillou E., Caron P., Briois S., Iacovoni J.S., Daburon V., Miller K.M., Jackson S.P., et al. Transcriptionally active chromatin recruits homologous recombination at DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:366–374. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larkin J., Goh X.Y., Vetter M., Pickering L., Swanton C. Epigenetic regulation in RCC: opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2012;9:147–155. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varela I., Tarpey P., Raine K., Huang D., Ong C.K., Stephens P., Davies H., Jones D., Lin M.L., Teague J., et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;469:539–542. doi: 10.1038/nature09639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalgliesh G.L., Furge K., Greenman C., Chen L., Bignell G., Butler A., Davies H., Edkins S., Hardy C., Latimer C., et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon J.M., Hacker K.E., Singh D., Brannon A.R., Parker J.S., Weiser M., Ho T.H., Kuan P.F., Jonasch E., Furey T.S., et al. Variation in chromatin accessibility in human kidney cancer links H3K36 methyltransferase loss with widespread RNA processing defects. Genome Res. 2013;24:241–250. doi: 10.1101/gr.158253.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu X., He F., Zeng H., Ling S., Chen A., Wang Y., Yan X., Wei W., Pang Y., Cheng H., et al. Identification of functional cooperative mutations of SETD2 in human acute leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:287–293. doi: 10.1038/ng.2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J., Ding L., Holmfeldt L., Wu G., Heatley S.L., Payne-Turner D., Easton J., Chen X., Wang J., Rusch M., et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481:157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al Sarakbi W., Sasi W., Jiang W.G., Roberts T., Newbold R.F., Mokbel K. The mRNA expression of SETD2 in human breast cancer: correlation with clinico-pathological parameters. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:290. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linehan W.M., Srinivasan R., Schmidt L.S. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: A metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2010;7:277–285. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duns G., Hofstra R.M., Sietzema J.G., Hollema H., van Duivenbode I., Kuik A., Giezen C., Jan O., Bergsma J.J., Bijnen H., et al. Targeted exome sequencing in clear cell renal cell carcinoma tumors suggests aberrant chromatin regulation as a crucial step in ccRCC development. Hum. Mutat. 2012;33:1059–1062. doi: 10.1002/humu.22090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J., Ghanim M., Xue L., Brown C.D., Iossifov I., Angeletti C., Hua S., Negre N., Ludwig M., Stricker T., et al. Analysis of Drosophila segmentation network identifies a JNK pathway factor overexpressed in kidney cancer. Science. 2009;323:1218–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.1157669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagai Y., Kojima T., Muro Y., Hachiya T., Nishizawa Y., Wakabayashi T., Hagiwara M. Identification of a novel nuclear speckle-type protein, SPOP. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:23–26. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhuang M., Calabrese M.F., Liu J., Waddell M.B., Nourse A., Hammel M., Miller D.J., Walden H., Duda D.M., Seyedin S.N., et al. Structures of SPOP-substrate complexes: insights into molecular architectures of BTB-Cul3 ubiquitin ligases. Mol. Cell. 2009;36:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q., Zhang L., Wang B., Ou C.Y., Chien C.T., Jiang J. A hedgehog-induced BTB protein modulates hedgehog signaling by degrading Ci/Gli transcription factor. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon J.E., La M., Oh K.H., Oh Y.M., Kim G.R., Seol J.H., Baek S.H., Chiba T., Tanaka K., Bang O.S., et al. BTB domain-containing speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) serves as an adaptor of Daxx for ubiquitination by Cul3-based ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:12664–12672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez-Munoz I., Lund A.H., van der Stoop P., Boutsma E., Muijrers I., Verhoeven E., Nusinow D.A., Panning B., Marahrens Y., van Lohuizen M. Stable X chromosome inactivation involves the PRC1 Polycomb complex and requires histone MACROH2A1 and the CULLIN3/SPOP ubiquitin E3 ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:7635–7640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408918102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geng C., He B., Xu L., Barbieri C.E., Eedunuri V.K., Chew S.A., Zimmermann M., Bond R., Shou J., Li C., et al. Prostate cancer-associated mutations in speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) regulate steroid receptor coactivator 3 protein turnover. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:6997–7002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304502110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li C., Ao J., Fu J., Lee D.F., Xu J., Lonard D., O'Malley B.W. Tumor-suppressor role for the SPOP ubiquitin ligase in signal-dependent proteolysis of the oncogenic co-activator SRC-3/AIB1. Oncogene. 2011;30:4350–4364. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li G., Ci W., Karmakar S., Chen K., Dhar R., Fan Z., Guo Z., Zhang J., Ke Y., Wang L., et al. SPOP promotes tumorigenesis by acting as a key regulatory hub in kidney cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:455–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theurillat J.P., Udeshi N.D., Errington W.J., Svinkina T., Baca S.C., Pop M., Wild P.J., Blattner M., Groner A.C., Rubin M.A., et al. Prostate cancer. Ubiquitylome analysis identifies dysregulation of effector substrates in SPOP-mutant prostate cancer. Science. 2014;346:85–89. doi: 10.1126/science.1250255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geng C., Rajapakshe K., Shah S.S., Shou J., Eedunuri V.K., Foley C., Fiskus W., Rajendran M., Chew S.A., Zimmermann M., et al. Androgen receptor is the key transcriptional mediator of the tumor suppressor SPOP in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5631–5643. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu M., Xu L.G., Zhai Z., Shu H.B. SINK is a p65-interacting negative regulator of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:27072–27079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu M., Wang P.F., Lee J.S., Martin-Brown S., Florens L., Washburn M., Shilatifard A. Molecular regulation of H3K4 trimethylation by Wdr82, a component of human Set1/COMPASS. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:7337–7344. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00976-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim S., Kim H., Fong N., Erickson B., Bentley D.L. Pre-mRNA splicing is a determinant of histone H3K36 methylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:13564–13569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109475108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Llorian M., Schwartz S., Clark T.A., Hollander D., Tan L.Y., Spellman R., Gordon A., Schweitzer A.C., Grange P. de la., Ast G., et al. Position-dependent alternative splicing activity revealed by global profiling of alternative splicing events regulated by PTB. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:1114–1123. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbieri C.E., Baca S.C., Lawrence M.S., Demichelis F., Blattner M., Theurillat J.P., White T.A., Stojanov P., Van Allen E., Stransky N., et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent SPOP, FOXA1 and MED12 mutations in prostate cancer. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:685–689. doi: 10.1038/ng.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]