Abstract

Introduction

Ocular infections remain an important cause of blindness worldwide and represent a challenging public health concern. In this regard, microbial keratitis due to fungal, bacterial, or viral infection can result in significant vision loss secondary to corneal scarring or surface irregularity. Left untreated corneal perforation and endophthalmitis can result, leading to loss of the eye. Rigorously studied animal models of disease pathogenesis have provided novel information that suggests new modes of treatment that may be efficacious clinically and emerging clinical data is supportive of some of these discoveries.

Areas covered

This review focuses on advances in our understanding of disease pathogenesis in animal models and clinical studies and how these relate to improved clinical treatment. We also discuss a novel approach to treatment of microbial keratitis due to infection with these bacterial pathogens using PACK-CXL and recommend increased basic and clinical studies to address and refine the efficacy of this procedure.

Expert commentary

Because resistance to antibiotics has developed over time to these bacterial pathogens, caution must be exercised in treatment. Attractive novel modes of treatment that hold new promise for further investigation include lipid based therapy, as well as use of small molecules that bind deleterious specific host responsive molecules and use of microRNA based therapies.

Keywords: Microbial keratitis, animal models, pathogenesis, clinical studies, treatment

1. Fungal keratitis

1.1 Background

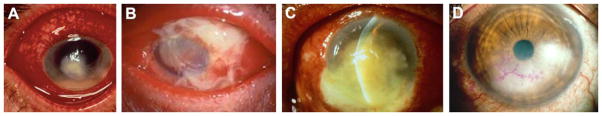

Fungal keratitis is an important cause of blindness worldwide and in industrialized countries such as the United States, contact lens wear is the primary risk factor [1–3], often associated with biofilm formation [4]. However, in disease resulting from trauma, ocular damage caused by plant material, insects or branches contaminated with fungal spores [5–7] are causative. After penetrating the corneal epithelium, conidia germinate and pass throughout the stroma and despite treatment, transplant is often required. In China and India, agricultural work is the major risk factor; fungal keratitis increases during the harvest season, because of increased airborne soil and contaminated plant materials [5–7, 8, 9]. In the corneal stroma, Aspergillus and Fusarium conidia germinate, and hyphae penetrate the stroma, causing ulceration, extreme pain, and visual impairment (Fig. 1A). Patients with fungal keratitis are immunocompetent compared with pulmonary or systemic fungally infected patients [10–13]. In fact, keratitis patients mount a vigorous immune response to Aspergillus and Fusarium hyphae characterized by infiltration of innate immune cells and upregulation of pro-inflammatory, chemotactic, and regulatory cytokines.

Figure 1.

Infectious keratitis. Shown are clinical infections of the eye due to fungal (Fusarium) disease (A); gram positive bacterial, S. aureus (B); gram negative bacterial, P. aeruginosa (C); and virus, HSV-1 (D) pathogens. Photos are courtesy of Dr. Mark McDermott, MD and Elicia Eby, MD, Kresge Eye Institute, Detroit, MI.

Innate immunity

1.2.1 PMN

Leal et al. [14] used both mouse model systems and human neutrophils (PMN) and found that these cells produced NADPH oxidase to control the growth of fungi. PMN antifungal activity depended on CD18, rather than the β-glucan receptor dectin-1. They also found that inhibiting thioredoxin increased the sensitivity of fungal hyphae to PMN-mediated killing in vitro. Others, [15] studied the effects of calprotectin, abundant in PMN, and showed that both zinc and manganese binding contribute to calprotectin’s anti-hyphal activity. However, PMN calprotectin played no role in killing intracellular fungal conidia. These studies demonstrated a stage-specific susceptibility of fungi (A. fumigatu) to zinc and manganese chelation by PMN-derived calprotectin. Leal et al. [16] also found that that dectin-1 dependent IL-6 production regulated expression of heme and siderophore binding proteins in infected mice. They also found that human PMN synthesize lipocalin-1 that restricts fungal growth. The studies may be supportive in considering alternative or adjunctive clinical treatment for corneal fungal disease.

1.2.2 IL-17 producing T cells

Taylor et al. [17] reported that mice that were immunized with fungal conidia before corneal infection had improved fungal killing and less opaque corneas compared to unimmunized animals. Immunity was associated with recruitment of PMN that produced IL-17, and T cells producing IL-17, but not IFN-γ. Karthikeyan et al. [18] tested the relevance of these animal data to human disease and examined IL-17 production in PMN from fungal keratitis patients, as well as uninfected people in southern India. IL-17 was detected in all groups, but levels were significantly higher in PMN from keratitis patients. They also reported no significant difference in plasma IL-17 when comparing patients with keratitis and normal controls.

1.2.3 TLRs, dectin-1 and cytokines

Toll-like receptors (TLR) and lectin-like-receptors play an important role in the innate immune response to fungi such as Candida albicans (C. albicans [19–21], resulting in cytokine production [22, 23]. Dectin-1 is a main fungal recognition component, and mice that are deficient in this molecule are more susceptible to fungal infection [24, 25]. In fact, it is dectin-1 amplification of TLR2- and TLR4 that facilitates production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [26] and apart from the TLRs, enhances IL-17, IL-6 and IL-10 [27]. Ferwerda et al. [28] in a clinical study reported that mutations in dectin-1 led to defective production of several cytokines after β-glucan challenge. Nonetheless, fungal phagocytosis and killing were normal.

2. Contact lenses and biofilms

Silicone hydrogel lenses with greater oxygen diffusion have not been found to reduce the risk of microbial keratitis [29], as was anticipated. In this regard, work in mice by Mukherjee et al. [30] showed that Fusarium grown as a biofilm on silicone hydrogel material induces keratitis upon injury to the cornea. They also showed that the ability to form biofilms is key in the pathogenesis of Fusarium in this animal model, and is likely true for human disease as well.

3. Drug treatments for fungal infection of the cornea

Twelve randomized controlled trials were conducted mainly in India [31]. The studies were small and at risk of bias, which meant that for most treatments it was impossible to determine which was better. However, three trials of just under 450 patients, compared topical natamycin to voriconazole. Solid evidence showed that patients receiving natamycin fared better in the sense that they were less likely to require a transplant (Table 1) when compared with patients treated with voriconazole. Dosage of natamycin was tested in a rabbit model [32]. They found that an optimized dosing schedule maintained natamycin concentration above tenfold of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) 90 and was based upon instillation every 5 hours. In addition, a 1/5th dose reduction of nanoformulation was effective. Whether this would improve clinical treatment with the drug has not been tested.

Table 1.

Experimental and Current Treatment Methods for Common Keratitis Inducing Microorganisms

| Organism

|

Class

|

Name

|

Target

|

References

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fusarium/Aspergillis | antifungal | natamycin | interferes with formation of fungal cell wall | 31, 32 |

| azole antifungal | topical voriconazole | interferes with formation of fungal cell wall | 31 | |

|

| ||||

| S. aureus | antibiotic | besifloxacin | DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV | 48, 50 |

| antibody | HCAbs | PVL leukocidins LukS-PV, LukF-PV | 51, 52 | |

| natural/alternative agents | Lysostaphin LasA (staphylolysin) |

bacterial peptidoglycan layer and cell wall | 35 | |

|

| ||||

| P. aeruginosa | Natural agents | resolvin E1 (RvE1) | reduction of proinflammatroy cytokines and PMN infiltration | 76 |

| glycyrrhizin | HMGB1 | Hazlett (unpublished data) | ||

| antibiotics | fluoroquinolones (3 & 4th generation) | DNA gyrase | 62 | |

|

| ||||

| Fungal/Bacterial | biomechanical | photoactivated chromophore for infectious keratitis (PACK-CXL) | creates new collagen/proteoglycan bonds antimicrobial | 82, 83, 84 |

|

| ||||

| Herpes virus | antiviral | topical ganciclovir gel | disrupts viral DNA synthesis | 90 |

| chemical (drug) | cyclosporine (CsA) | immunosupressant | 115 | |

4. Bacterial keratitis

4.1 Background

Bacterial keratitis is a devastating ocular infection that can lead to blindness if adequate and timely treatment is not initiated. There are many risk factors for bacterial keratitis including ocular trauma, surgery, immunosuppression, and contact lens use. As of 2014, there are 40.9 million contact lens wearers over 18 years of age in the USA, accounting for 1 million visits to health care professionals for keratitis, at an estimated cost of $175 million [33]. The species of the invading organism and the virulence factors they utilize determines the pathogenesis of the infection [34].

4.2 Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)

S. aureus was first identified after isolation from a surgical abscess by Sir Alexander Ogston in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1880 [35]. S. aureus is a leading cause of keratitis worldwide. From 1993–2012, S. aureus accounted for 25.2% of 1576 bacterial keratitis isolates with other staphylococcus species comprising 9.5% [36]. S. aureus possesses a number of factors that allow for increased host adhesion, cytolytic activity against host cells, and the ability to evade the innate immune system and is therefore considered the most virulent of the Staphylococcus species [36].

4.3 Adherence

S. aureus uses collagen and fibronectin to adhere to corneal epithelial cells, thus initiating keratitis. A rabbit model, in which contact lenses soaked in S. aureus strains containing the collagen-binding adhesin (Cna+) or its isogenic mutant lacking the adhesin (Cna−) were placed on the injured cornea and outcome showed that Cna significantly contributed to bacterial adherence and colonization of the cornea [37]. The ability of S. aureus to adhere to and invade host cells via fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBP) was examined in vitro using cultured human corneal epithelial cells (HCEC). These studies found that FnBP may allow binding to the corneal epithelium, and that ligation of the appropriate receptor (α5β1 integrin is proposed) leads to actin polymerization, formation of endocytic vesicles and invasion [38].

5. Toxins

5.1 Alpha toxin

The most studied virulence factors of S. aureus are its toxins. Alpha (α)-toxin is lytic to red blood cells and a series of leukocytes, but not PMN [39] and a model using rabbits confirmed that S. aureus α-toxin is a major factor in pathogenesis. Direct application of purified α-toxin led to erosion of the corneal epithelium and stromal edema [40]. It binds to a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 (ADAM10), a high affinity α-toxin receptor, resulting in conformational changes that are required for binding to eukaryotic cells. In addition to mediating the toxicity of α-toxin, this binding leads to disruption of focal adhesions [41, 42], such as E-cadherin in epithelial cells, resulting in loss of epithelial barrier function allowing pore formation [43]. In addition, iritis, including blanching and loss of light constriction reflex resulted after treatment with purified α-toxin. In support of these findings, strains of S. aureus, deficient in α-toxin caused less corneal edema than the wild type parent strain [40].

5.2 Beta toxin

Similar testing of beta (β)-toxin showed that purified β-toxin elicited an edematous reaction of the sclera. This response was consistent with the fact that β-toxin is known to exhibit sphingomyelinase activity and was active on the excessive sphingomyelin content of the scleral epithelial cell membrane. Mutant bacteria, lacking β-toxin were less virulent [40].

5.3 Delta toxin

S. aureus delta (δ)-toxin, δ-hemolysin, is a phenol-soluble modulin (PSM). Small, amphipathic peptides with detergent like properties, PSMs have multiple functions in staphylococcal infections and can be highly cytolytic. Most strains of S. aureus produce PSMs and it is this type of toxin, specifically PSMα and leukocidin LukAB (LukGH) that lyse PMN after bacterial phagocytosis. This mechanism is extremely important for the elevated toxicity found in the most aggressive S. aureus strains [39].

6. Experimental models

Most of the experimental models examining virulence factors for S. aureus have used in vitro systems or rabbit models, the latter of which is lacking in reagents to facilitate investigation of the host response and its contribution to corneal damage. Nonetheless, a study using C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice examined the immune response to a clinical and laboratory strain of S. aureus. They found that unlike Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) keratitis, C57BL/6 mice were resistant to S. aureus infection, whereas, BALB/c mice were susceptible. The results from this study also demonstrated that the strain of S. aureus may be critical in determining the host response and clinical outcome of infection. The two strains of S. aureus not only produced different severity of infection, but showed that viable bacterial number, infiltrating PMN number and cytokine production differed between mouse strains. In addition, anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 were significantly higher in resistant C57BL/6 mice, supporting the tenet that they are protective in S. aureus induced keratitis [44].

7. Clinical assessment and treatment

Due to the serious, sight-threatening potential of bacterial keratitis, early diagnosis and identification of the infecting species is critical for adequate treatment. Patients with keratitis often present with one or more symptoms including eye pain, decreased vision, redness, or tearing [34]. Treatment with a fortified antibiotic (cefazolin 5% and tobramycin or gentamicin 1.4%) [45] is often initiated prior to receiving results of bacterial smears or cultures. This is common in instances for ulcers less than 2 mm in dimension, when broad-spectrum antibiotics may be started if smears are negative and before culture reports are available [36]. Because of their broad-spectrum anti-bacterial activity and relatively low toxicity, topical fluoroquinolones, particularly gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin have become important treatment options for common ocular bacterial infections [46]. They also possess added advantages to fortified antibiotics in terms of longer shelf life, and better stability without requiring refrigeration [45]. Topical ocular application of antibiotics is the most convenient route of administration, however, it is extremely labor intensive and involves application of drops every half hour for 48 hours or longer. In addition, adjunctive treatment using topical steroids was shown in a multicentric, randomized clinical trial Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial (SCUT) to provide no added benefit for S. aureus [47]. The unique structure of the eye, the physicochemical properties o antibiotics, and emerging antibiotic resistance of many S. aureus strains pose significant challenges to treating this devastating disease (Fig. 1 B).

8. Challenges and developing new treatments

Use of MIC is the most common measure of in vitro susceptibility. When evaluating systemic therapy, the MIC combined with the pharmacokinetics (PK) of the drugs to determine the pharmacodynamic (PD) indices can differentiate susceptible from non-susceptible pathogen populations [46]. It must be noted that there are no susceptibility standards for topical therapy. Topical ocular antibiotics may likely result in higher concentrations at the corneal surface than would be present following systemic administration. Unfortunately, these concentrations are quickly diminished by reflex tearing and blinking after instillation. Since there is currently no standard to measure efficacy of topical therapies, it must be assumed that antibiotic concentrations reached in the ocular tissues are at an equal or greater concentration than would be seen in the serum [36]. Studies have been done in animal and human models to determine PK concentration of topical antibiotics used in ocular disease. Combining this information with MIC data provides the potential to predict clinical efficacy [46], however the issues with drug delivery are only one of the many challenges to treating ocular infections.

9. Resistant strains

The development of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is a significant clinical problem with regards to appropriate and effective treatment. Resistance has developed over time and is due to many factors: extended prophylaxis, overuse of antibiotics for systemic infections, in agriculture, sub-therapeutic doses and misuse for non-bacterial infections, as well as specific bacterial species, that predispose them to resistance [48]. Emergence of MRSA strains, resistant to the most commonly used fluoroquinolones has resulted in the necessity to develop new antimicrobials for bacterial keratitis. Besifloxacin, the first topical chlorofluoroquinolone was developed solely for ophthalmic use. It inhibits DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, ubiquitous in bacteria and essential for bacterial survival [49] (Table 1). The importance of this dual functionality is that two mutations would be necessary to convey resistance and it is equally effective against gram positive and gram negative organisms. As it is not indicated for systemic use, the possibility of developing resistance subsequent to systemic treatment is not a factor. It has been shown to be effective in a rabbit model of keratitis and reduced MRSA colony-forming units more effectively than gatifloxacin or moxifloxacin [48]. A retrospective study showed that besifloxacin treatment of human cases of bacterial keratitis yielded no serious adverse effects and had low incidences of corneal scarring or neovascularization similar to that seen with moxifloxacin treatment [50].

10. Targeting virulence factors

The focus on development of new, more effective antibiotics to combat resistance is only one way to pursue treatment of S. aureus. New strategies that target staphylococcal virulence factors rather than killing the bacteria have become popular, as these treatments will be less likely to lead to resistance. The production of toxins by S. aureus, specifically the leukocidins, provide an attractive objective for development of novel treatments. Unfortunately, to interfere with the function of one leukocidin is not sufficient to dampen the virulence of the organism. A more effective tactic would be to shut down Pmt, an ABC transporter that is needed for the secretion of all PSM peptides. Absence of Pmt results in bacterial death due to the accumulation of dangerous cytosolic levels of PSM. Blocking Pmt action with a monoclonal antibody would abolish the activity of an entire family of toxins with multiple functions in the pathogenesis of S. aureus in addition to the possibility of being applicable to other staphylococcal strains. The amount of required antibody would be less than if blocking the toxins separately, as there are fewer Pmt transporters to block when compared to individual toxins. The challenge to creating such a treatment is finding a monoclonal antibody with the ability to penetrate the bacterial cell wall to reach the Pmt system located in the membrane [51]. To this end, humanized heavy chain-only (HCab) antibodies against Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) components (LukS-PV, LukF-PV), with an engineered tetravalent bispecific HCab (Table 1) tested in vitro and in vivo in a rabbit model prevented toxin binding and pore formation. These HCabs inhibited inflammatory reactions and tissue destruction and show potential for use as a complement to antimicrobial treatments [52].

The use of already existing agents to treat MRSA is also being studied. Lysostaphin is a zinc metalloproteinase extracted from S. simulans that lyses S. aureus by disrupting its peptidoglycan layer (Table 1). It is effective in MRSA keratitis and endophthalmitis [35]. Las A protease (staphylolysin) targets the peptidoglycan of S. aureus and was comparable to vancomycin when treatment was begun early. Surprisingly it was more effective when treatment was begun in the late phase of infection, suggesting that Las A can lyse bacterial cell walls during the stationary growth phase [35].

With the advancement of research on anti-staphylococcal drugs, the future of therapy is much less ominous than in years past. Despite the fact that a broadly protective vaccine against staphylococcal infections is still unattainable, new antibiotics, anti-virulence drugs and antibodies as alternative treatments that are in pre-clinical development will facilitate better control staphylococcal infections and allow further investigation into more efficacious therapeutics.

11. Pseudomonas aeruginosa

P. aeruginosa is a gram negative bacterium found widely dispersed in the environment [53] and causes both acute and chronic infections in humans. P. aeruginosa acute infections include bacterial keratitis, otitis externa, bacteremia, pneumonia and burn wound infections, while lung inflammation in cystic fibrosis is one of the most severe chronic infections caused by this bacterium [54]. Keratitis is one of the most severe infections of the eye and it is one of the leading causes of corneal ulcers worldwide [55]. Use of soft, extended wear contact lenses is the major risk factor in the US and other developed countries, whereas trauma to the eye, especially in agricultural accidents, is the major risk factor in less industrialized areas [56]. Pseudomonas keratitis presents as a suppurative stromal infiltrate with mucopurulent exudate, epithelial edema, yellowish coagulative necrosis with stromal ulceration and a ring infiltrate in the paracentral cornea surrounding corneal ulcers, [55] (Fig. 1C). If untreated, or non-responsive to topical treatment, perforation may occur which may necessitate a transplant which is a medical hardship; economically, an annual cost to treat keratitis in the US is a financial burden as well [33, 56].

11.1 Virulence factors

P. aeruginosa expresses numerous virulence factors including cell associated structures such as pili and non-pili adhesins and extracellular products including proteases, hemolysins, exoenzymes and exotoxins. These are required for P. aeruginosa to invade the cornea and exert resistance against host defense mechanisms to cause host tissue damage. Since the corneal surface is protected by antibacterial agents and the tightly packed nature of the corneal epithelium, infection typically requires a breach in the epithelial barrier which may result from use of contact lenses, immunodeficiency and/or ocular trauma [57, 58]. As the first step in pathogenesis, pili, non-pili adhesins and the glycocalyx of P. aeruginosa mediate attachment to the altered corneal epithelium, binding to corneal epithelial receptors. The glycocalyx also prevents phagocytosis of invading P. aeruginosa by host immune cells [54]. P. aeruginosa releases several extracellular products that facilitate stromal invasion of the bacterium causing corneal tissue damage. Proteases such as elastase and alkaline protease degrade basement membrane and extracellular matrix and cause cell lysis [56]. In addition, these proteases and exotoxin A interfere with host defenses by degrading proteins such as immunoglobulin A and surfactant protein D [54]. Further, ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of exotoxin A inactivates elongation factor 2, inhibiting host protein synthesis [56]. Invasion and dissemination of P. aeruginosa is also facilitated by exotoxins released by the type III secretion system (TIIISS) which secretes exoS, exoT and exoU. ExoS and exoT activity promote bacterial survival and spreading by inducing apoptosis of infiltrating PMN [57]. ExoU has phospholipase activity and promotes stromal tissue necrosis and inflammation [57].

12. Host response

During an infection, P. aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and flagella bind to host cell surface receptors including, but not limited to, TLR2, TLR4 and TLR5 [58]. Interactions initiate a signaling cascade in resident macrophages and corneal epithelial cells to produce inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines, which then promote recruitment of inflammatory cells such as PMN to the site of infection. These cells are essential for eradication of invading bacteria, but their excessive, uncontrolled activation also contributes to the severity of pseudomonas keratitis [55,58]. For instance, elevated expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) and IL-1β, known chemoattractants for PMN [55] is consistent with increased disease severity, PMN infiltrate and bacterial load detected in P. aeruginosa infected susceptible C57BL/6 mice (cornea perforates) compared to resistant BALB/c mice (cornea heals) [55]. Inhibition of IL-1β improves disease outcome in C57BL/6 mice with reduced PMN in the infected cornea. In addition to phagocytosis, PMN recruited to the corneal stroma produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) including collagenases to prevent microbial dissemination [58]. However, ROS and MMPs also cause bystander damage to the cornea by disrupting the collagen matrix which causes corneal scarring, loss of corneal clarity and impaired visual acuity. Other studies [59] showed that HIF-1α, a transcription factor, is essential for effective PMN bacterial killing, antimicrobial peptide production and PMN apoptosis. In addition to PMN, CD4+ T cells and Langerhans cells, the latter especially in contact lens wear, migrate to the site of infection and contribute to the host immune response against P. aeruginosa [55]. It was shown that depleting CD4+ T cells in infected C57BL/6 mice prevented corneal perforation, while in controls, corneal perforation was observed 7 days after infection [55]. More recently, Suryawanshi et al. [60] found that infection in C57BL/6 mice also induced a strong Th17 mediated corneal pathology and that treatment with galectin-1 was efficacious. In contrast IL-10 was found of importance in the resistance response of BALB/c mice as recombinant IL-10 treatment rescued rapamycin treated mice that had decreased IL-10 levels, improving disease outcome [61].

13. Antibiotics

The objective of antibiotic therapy is to rapidly eliminate the corneal pathogen. Monotherapy with fourth generation fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin or gatifloxacin are the current, most commonly used antibiotic therapy [62]. However, P. aeruginosa has high ability to trigger antibiotic resistance mechanisms making them difficult to eradicate even using current treatments [63]. For instance, inefficient porins in the P. aeruginosa outer membrane limit the rate of antibiotic penetration to the bacterial cell which results in efflux pump overexpression and enzymatic antibiotic modification [63]. In addition P. aeruginosa acquires spontaneous genetic mutations based on the antibiotic therapy and the environment and transfers those mutated genetic elements horizontally between cells, further reducing its susceptibility to antibiotics [63]. Recently, it was reported that inappropriate use of antibiotics along with other risk factors caused a breakthrough resistance in P. aeruginosa, which resulted in emergence of multi-drug resistant (MDR), extensively drug resistant (EXD) and pan-drug resistant (PDR) P. aeruginosa strains with no or minimum effective antibiotic therapy [63, 64]. Encounter with these highly resistant bacteria poses immense therapeutic challenge. For instance recurrence of P. aeruginosa ocular infections after cataract surgery or epipolis laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (epi-LASIK) are mostly MDR, requiring reconstituted systemic antibiotics for topical use and advanced surgical procedures to treat the disease [65].

14. Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid therapy is used with the aim of reducing the host inflammatory response initiated by bacterial toxins and the lytic enzymes released by PMN, which obstructs corneal healing after infection [66]. However in P. aeruginosa keratitis, corticosteroid treatment may slow corneal wound healing, extend the infection period and induce stromal thinning and perforation. It was also reported that patients receiving corticosteroids before P. aeruginosa keratitis are at high risk for adverse effects of keratitis [47]. The impact of adjunctive corticosteroid therapy given concurrently with antibiotics to treat P. aeruginosa keratitis is controversial. In this regard, Sy et al. [67] performed a sub analysis on data collected in the SCUT to particularly analyze the impact of adjunctive corticosteroid therapy on the clinical outcome of P. aeruginosa keratitis. No significant benefit nor worsening effects were seen with corticosteroids. However, another sub-group analysis of SCUT focusing on cytotoxic (ExoU) vs invasive (ExoS) subtypes of P. aeruginosa revealed that adjunctive corticosteroid therapy initiated at 48 h after antibiotic treatment is beneficial for resolution of keratitis caused by invasive strains [68, 69].

15. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and proteins

15.1 Beta defensins

β-defensins are natural peptides produced by corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells. These peptides are cationic and interact with bacterial membranes composed of negatively charged LPS. Such interaction enhances bacterial cell membrane permeability and cell lysis [70]. Using siRNA knockdown of mouse beta defensins (mBD) mBD2 and mBD3 in C57BL/6 mice, it was reported that both mBD2 and 3 enhanced resistance to disease [71]. Studies also revealed that mBD2 and mBD3 function together to regulate the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators, PMN infiltrate and bacterial load in the infected cornea.

15.2 VIP and other peptides

Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) is an anti-inflammatory neuropeptide with multiple functions that was shown to balance pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the P. aeruginosa infected cornea and protect C57BL/6 mice against corneal perforation [72].

OH-CATH30 is a natural peptide found in snakes. Li and coworkers [73] reported that OH-CATH30 is protective in keratitis induced by 10 different antibiotic resistant clinical isolates of pseudomonas. Using a rabbit keratitis model they showed OH-CATH30 itself, or as an adjunctive therapy with levofloxacin, reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β), leukocyte infiltration, bacterial load and improved disease. OH-CATH30 demonstrates an approximately 6 μg/mL MIC for the P. aeruginosa strains tested [73].

Thrombomodulin is a multi-domain transmembrane protein with anti-inflammatory properties found in corneal epithelium and stromal cells. Using a P. aeruginosa infected C57BL/6 mouse model, McClellan et al. [74] reported that treatment with the recombinant protein protects against pseudomonas keratitis. Treatment reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines while upregulating anti-inflammatory molecules, but did not decrease levels of the alarmin high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) which is a good target for treatment, as it is upregulated later in disease, making it attractive clinically.

Despite demonstrating various protective effects of AMPs and proteins for P. aeruginosa induced keratitis, there are challenges to clinical use. These small peptides and proteins act effectively in their native α-helical or β-sheet confirmation. However, extraction or synthetic conditions, as well as enrichment (for instance to add tags to facilitate delivery to the cell) may lead to adoption of a random coiled structure instead of the native confirmation which would retard the activity of these molecules. In addition, the ability of these molecules to penetrate the cornea, the residence time and the stability in the ocular environment in the presence of a wide variety of proteases and other inhibitors are other issues of concern which must be addressed.

16. New frontiers in treatment

16.1 Lipid-based therapy

Lipid based therapy uses essential fatty acids, resolvins and cyclooxygenase inhibitors to modulate inflammatory processes associated with the ocular surface such as bacterial keratitis [75]. Resolvins are metabolites of the polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [75]. Resolvin E1 (RvE1), a metabolite of EPA demonstrates anti-inflammatory effects by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production, PMN migration and tissue destruction. Further RvE1 also promotes PMN clearance by recruiting non-inflammatory monocytes and macrophages [75]. Recently, using a C57BL/6 mouse model, Lee and coworkers [76] revealed that RvE1 treatment protects against corneal infection induced by LPS, and antibiotic killed S. aureus or P. aeruginosa. RvE1 treatment significantly decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in human PMN and corneal epithelial cells (IL-8, IL-6, CXCL1), murine macrophages (IL-1β, TNF-α, CXCL1) and murine cornea (CXCL1). Further RvE1 treatment inhibited PMN infiltrate to the corneal stroma and reduced corneal thickness and haze. These data suggest that RvE1 could hold promise as an effective adjunctive therapy to treat ocular infections caused by P. aeruginosa (Table 1).

LPS (lipid A), binds to TLR4 to initiateTLR4/MD-2 signaling inducing the host immune response. Eritoran is structurally similar to lipid A and acts as a TLR4 antagonist. Eritoran tetrasodium (E5564) inhibited LPS or P. aeruginosa induced corneal infection by reducing chemokine production and the PMN infiltrate [77].

Despite, the successful application of lipid-based therapy (such as RvE1 and Eritoran) to treat ocular infections in pre-clinical models, their use in a clinical setting is still challenging. For instance, in order to treat ocular infections in humans these lipids need to be enriched and further characterized. However, their structural complexity restricts such requirements.

16.2 High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)

HMGB1, a small 215 amino acid protein is an alarmin, belonging to the family of danger associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) which amplify inflammatory reactions. HMGB1 is an extracellular mediator of pro-inflammatory responses and strategies to inhibit the molecule in various diseases are being tested. McClellan et al. [78] reported that silencing HMGB1 using small interfering RNA (siHMGB1) significantly improved disease outcome of pseudomonas keratitis in susceptible C57BL/6 mice. HMGB1 knockdown downregulated pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, while upregulating anti-inflammatory cytokines. Treatment also downregulated IL-1β and MIP-2, reducing the PMN infiltrate. Since knockdown of HMGB1 would not be desirable clinically, this group (Hazlett laboratory) is pursuing use of other molecules such as glycyrrhizin, a natural anti-inflammatory and antiviral triterpene, to reduce HMGB1. Preliminary experiments in mice using invasive (clinical isolate) and cytotoxic (ATCC strain 19660) pseudomonas strains, revealed that treatment reduced HMGB1 levels, bacterial plate count, inflammatory consequences and disease outcome, even when topical treatment was delayed for 6 hours after infection (Hazlett, unpublished data) (Table 1).

16.3 MicroRNA (miR)

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs ubiquitously expressed in diverse organisms that function to post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression. Many miRNAs expressed at the ocular surface are upregulated in response to microbial virulence factors and function to regulate ocular innate immunity; included are miR-132, miR-17-92 and miR-155 [79]. miR-155 regulates differentiation and function of regulatory and helper T cells, as well as pro-inflammatory cytokine expression [79]. Using P. aeruginosa infected C57BL/6 mice, control or miR-155 knockout and corneal scraping samples from human patients with P. aeruginosa keratitis, Yang et al. [79] reported that upregulation of miR-155 expression in response to P. aeruginosa suppresses bacterial clearance and enhances corneal susceptibility. This study also reported that miR-155 was significantly upregulated in macrophages, but not PMN. Upregulation of miR-155 prevented macrophage mediated P. aeruginosa phagocytosis and bacterial killing by targeting Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb). In addition, knockdown of the miR-183/96/182 cluster [80] in mice enhanced resistance to P. aeruginosa infection compared to their wild type littermates [81]. Inactivation of miR-183/96/182 downregulated the expression pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, MIP-2), neuropeptides (substance P), PMN infiltrate and bacterial load in the infected cornea, while significantly decreasing the severity of corneal disease [81]. Since miR-155 and miR-183/96/182 knockout mice demonstrate more resistance to P. aeruginosa infection compared to control groups, targeting these miRNA may provide a novel, clinical approach to treat keratitis.

16.4 Corneal cross-linking

Corneal cross-linking (CXL) and more specifically, PACK-CXL (photoactivated chromophore for infectious keratitis-CXL) is a new therapeutic approach to treat infectious corneal diseases [82]. The technique employs riboflavin drops and 365 nm ultraviolet-A light to generate additional cross-links in the cornea. Specifically, the riboflavin acts as a chromophore and releases free radicals, creating new bonds between collagen fibers and proteoglycans. These additional cross-links increase the overall biomechanical strength of the cornea [82].

In a small trial, five patients were enrolled including three patients with mycobacterial keratitis and two others with fungal keratitis [82]. All cases had been unresponsive to regular topical and systemic treatment and had developed corneal melting. CXL was effective not only in stabilizing a melted cornea, but more importantly, in killing pathogens of different origins in advanced and therapy-resistant keratitis. Additional case studies on the effect of CXL treatment on melting corneas showed similar results [82, reviewed]. Larger trials also showed that the technique was efficacious [82]. In fact, in advanced cases of corneal melting, in the majority of cases seen, melting was stabilized and emergent a chaud keratoplasty avoided [83].

CXL might be effective not only in treating advanced ulcerative infectious keratitis as an adjuvant, but also for treating early-stage bacterial infiltrates as first-line treatment. CXL’s antimicrobial effect is due to the effect of UV light interacting with riboflavin as the chromophore. UV light damages both the DNA and RNA of pathogens and renders them inactive [82, reviewed]. As microbial resistance to antibiotics increases, new lines of treatment will be needed and thus CXL may be a promising alternative or adjunct to current therapy. Both a recent animal study [84] using S. aureus induced ulcers in the rabbit as a model and a study involving 32 patients with moderate bacterial corneal ulcers [85] provide positive data to support this tenet. In fact, in the patient study, CXL treatment accelerated epithelial healing and shortened treatment time. Nonetheless, as pointed out by Chan et al. [86] questions and lack of consensus around the use of CXL for infectious keratitis remain. More basic and clinical studies appear warranted as the potential for this technique to resolve many current issues in the care of infectious keratitis patients appears promising. In addition, as pointed out in a recent review, careful modification of CXL to improve its efficiency could lead to improved treatment in specific clinical settings and for select pathogens [83].

17. Herpes Stromal Keratitis (HSK)

17.1 Background

Corneal infection with herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) remains a leading cause of unilateral infectious corneal blindness in the United States and worldwide [87]. The majority of corneal HSV-1 infection is not the outcome of primary ocular infection, but in response to reactivation of latent virus from the sensory neurons of the trigeminal ganglion (TG). Once reactivated, infectious virus or viral proteins traffic through axons of TG’s ophthalmic branch and enters into the corneal epithelium via sensory nerve terminals [88]. Frequently, infection of the corneal epithelium causes the development of herpes epithelial keratitis (HEK), an outcome of viral cytopathic effects [89]. Virus induced epithelial lesions are mostly self-limiting but heal more rapidly when given topical or oral anti-viral drug treatment such as trifluridine solution, vidarabine ointment or acyclovir and famciclovir, respectively. In addition, topical ganciclovir ophthalmic gel (0.15%) is widely used to treat acute herpetic keratitis [90]. The advantage of ganciclovir treatment involves low corneal toxicity, gel formulation and the less frequent applications required in comparison to other anti-viral drugs (Table 1). However, recurrent corneal epithelial infection with HSV-1 can have stromal involvement with or without damage to overlying corneal epithelium and is known as herpes stromal keratitis (HSK). In patients, HSK can be necrotizing, involving corneal epithelial defect, non-necrotizing or a mix of both [91]. Stromal inflammation is the hallmark of both clinical categories of HSK. Clinical signs of HSK involve stromal opacity, edema, and neovascularization of an inflamed cornea and require immediate medical attention (Fig. 1D).

18. Current drug treatments for HSK and shortcomings

The multicenter clinical trial conducted as part of herpetic eye disease study (HEDS) determined that topical anti-viral therapy (1% trifluridine ophthalmic solution) given along with a tapering dose of topical corticosteroids was effective in significantly reducing the stromal inflammation and progression of HSK [92, 93]. On the other hand, long-term oral acyclovir prophylactic treatment given to patients with a history of stromal involvement was shown to prevent the recurrence of herpetic corneal disease [94]. However, long term treatment with acyclovir is effective against replicating virus but does not prevent viral reactivation. Similarly, recurrent use of corticosteroids for a longer time-period to control HSV-1 induced stromal inflammation may result in the development of glaucoma or cataract. Thus, there is pressing need to develop novel experimental approaches to either prevent the development of HSK or control ongoing stromal inflammation in order to preclude penetrating keratoplasty, the final outcome for scarred corneas.

19. Recent developments in understanding viral clearance and pathogenesis of HSK

The current understanding of HSK is largely derived from experiments carried out in murine models. Studies in mice after primary ocular HSV-1 infection have shown the involvement of immune system components in viral clearance and pathogenesis of HSK.

19.1 Innate and adaptive immunity mediated control of ocular HSV-1 infection

PMN are long considered as key immune cells involved in controlling viral load in HSV-1 infected corneas. However, recent findings, using reagents to specifically deplete PMN, showed that inflammatory monocytes (IM), but not PMN, play an important role in controlling viral load at an early time-point after corneal HSV-1 infection [95]. Early depletion of corneal resident dendritic cells (DCs) was shown to reduce the influx of NK cells in infected corneas suggesting the indirect role of corneal DCs in controlling HSV-1 infection [96]. In addition, type I interferon produced by corneal epithelial cells in HSV-1 infected corneas has been shown to control viral load by recruiting IM [95]. Type I interferon production in response to HSV-1 infection is independent of TLR signaling and is regulated by a novel innate DNA sensor (IFI-16) [97]. Even though innate immune cells are essential in controlling viral load in HSV-1 infected corneas, the importance of adaptive immunity, especially CD8+ T cells, in the clearance of HSV-1 from infected corneas has recently been shown in a mouse model of primary ocular HSV-1 infection [98]. However, it is not clear whether these cells are cytopathic and are involved in causing corneal epithelial or stromal tissue damage by degranulation of their cytotoxic granules.

19.2 Role of IL-17 and Foxp3+ Treg in HSK pathogenesis

Seminal studies carried out in murine models have shown CD4+ T cells as a principle mediator of HSK [99]. After ocular HSV-1 infection, infiltrating but not resident corneal DCs were shown to take up viral antigens and traffic to draining lymph nodes to prime virus specific CD4+ T cells [100]. The latter migrate to infected corneas and orchestrate tissue damage. Recently, IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells were detected in inflamed corneas during later stages of disease and IL-17−/− mice were shown to develop significantly reduced ocular lesions [101]. IL-17 producing gamma delta (γδ) T cells also were shown to infiltrate HSV-1 infected corneas at early time points after infection. However, it is not clear whether IL-17 production by γδ T cells during active viral infection is beneficial or not. IL-17 expression has also been noted in human HSK patients, suggesting the involvement of this cytokine in HSK pathogenesis [102]. Because of the involvement of pathogenic CD4+ T cells in HSK, the role of Foxp3 expressing regulatory CD4+ T cells in controlling HSK was studied in a mouse model. In vivo treatment with the fungal metabolite drug FTY720 was shown to increase the Foxp3+ Treg population, significantly diminishing HSV-1 induced ocular lesions [103]. However, discontinuation of the treatment resulted in relapsed inflammatory lesions. Similarly, in vivo expansion of Foxp3+ Tregs during the early stages of corneal HSV-1 infection, using IL-2/anti-IL-2 complex, was shown to reduce the development of HSK lesions but, the increased Treg therapy was not effective once pathogenic CD4+ T cells were primed and infiltrated the infected corneas, a more clinical situation [104]. Together, these studies suggest that increasing the Foxp3+ Treg population alone is not an effective approach to control ongoing stromal keratitis lesions.

19.3 Role of hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in HSK

One of the prominent features of HSK involves neovascularization of infected corneas. Blood vessels sprouting from the limbal area were shown to invade the avascular cornea after ocular HSV-1 infection. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) produced in HSV-1 infected corneas plays an important role in corneal neovascularization. In addition, it is documented that HSV-1 infection reduces the bioavailability of soluble VEGF receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1), a molecule that chelates and inactivates VEGF [105]. The reduction of sVEGFR-1 requires MMP-9 produced by infiltrating PMN in infected corneas. Although VEGF-A is considered as a major player in neovascularization of HSV-1 infected corneas, the possibility of anti-angiogenic or other angiogenic factors in regulating VEGF-A action in virus infected corneas cannot be ruled out. Mice lacking Robo4, an endothelial receptor that counteracts VEGF downstream signaling, have been shown to have increased angiogenesis compared with control mice after ocular HSV-1 infection [106]. On the other hand, microRNA 132 (miR-132) is reported to enhance VEGF-A mediated angiogenic action and silencing miR-132, using anti-miR-132 nanoparticles, reduced angiogenesis in HSV-1 infected corneas [107]. In addition to neovascularization, HSV-1 infected corneas have recently been shown to have extensions of lymphatic vessels from the limbal region. Unlike non-infectious lymphangiogenesis reported during corneal transplantation, HSV-1 induced lymphangiogenesis is dependent on VEGF-A produced by virus infected corneal epithelial cells [108]. In addition to VEGF-A, VEGF-C released from CD8+ T cells infiltrating the infected corneas have also been shown to promote the invasion of lymphatic vessels into central cornea [98]. Lastly, pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 potentiate the action of VEGF to promote virus induced lymphangiogenesis in infected corneas [109]. Additional studies are warranted to define the clinical significance of lymphangiogenesis in regulating HSK pathogenesis.

20. Novel aspects of altered corneal homeostasis in HSK

In addition to involvement of immune components in the pathogenesis of HSK, the alteration in homeostasis of corneal resident cells may also play an important role in initiation and or progression of HSK. In a recent study, using in vivo confocal microscopy, changes in corneal nerve density and branching of nerve trunks were determined in patients with herpes simplex keratitis. The study showed that in comparison to normal subjects, HSV-1 infected patients display a significant reduction in corneal nerve density and loss of corneal sensation in both infected as well the contralateral eye [110]. Similarly, in a mouse model of HSK, reduced corneal innervation was detected in the corneal epithelium during the clinical period of disease [111, 112]. Suturing of eyelids (tarsorrhaphy), after ocular HSV-1 infection, prevented the corneal desiccation and loss of corneal nerves. Tarsorrhaphy reduced the severity of HSK suggesting that inhibiting the retraction of nerves from infected corneas could play an important role in controlling HSK severity. Corneal nerve terminals are in close association with superficial corneal epithelial cells and thus, alteration in the corneal epithelium of HSV-1 infected eyes may have an effect on corneal innervation. In fact, a hyperreflective phenotype of desquamating superficial corneal epithelial cells is reported in diseased eyes of patients with herpes simplex keratitis, suggesting an altered corneal epithelial morphology [113]. Future studies should determine the underlying cause of alteration in corneal epithelial morphology in HSK patients and whether pharmaceutical approaches to maintain normal corneal epithelial morphology have an effect on underlying stromal inflammation in diseased corneas.

21. Future perspective in management of HSK

HSK is primarily due to reactivation of latent virus from TG and thus, novel approaches including the development of a therapeutic vaccine to keep the virus in latency should decrease the incidence of HSK. Thus, there is a strong need to understand the neurobiology and immunology of HSV-1 latency. In humans, HSK frequently follows previous episodes of HSV epithelial keratitis but not all clinical cases of HEK result in the development of HSK. Similarly, in a mouse model of primary ocular HSV-1 infection, not all eyes infected with HSV-1 develop severe stromal keratitis even though infected corneas are infiltrated with immune cells [114]. Thus, better understanding of the events involved in transition of HEK to HSK could provide a novel approach to prevent the development of HSK. Therapeutically, alternative approaches to corticosteroid treatment are required to manage ongoing HSK. One such approach involves the use of topical cyclosporine (Table 1), which has been shown to effectively resolve stromal inflammation in a small group of patients with non-necrotizing or necrotizing HSK [115].

22. Expert commentary

Corneal infections remain an important cause of blindness throughout the world and are a challenging public health concern with the need for more effective treatment. In this regard, microbial keratitis due to fungal, bacterial, or viral infection, particularly HSV, can result in significant vision loss secondary to corneal scarring and other adverse events. If treatment for fungal or bacterial keratitis is delayed or if left untreated, corneal perforation and endophthalmitis can result, leading to loss of the eye. Rigorously studied animal models of disease pathogenesis reveal the interplay between host and microbe and have provided novel information that target various signaling pathways or new modes of treatment that may be efficacious clinically; emerging clinical data is supportive of some of these discoveries and more studies are needed in this area. Because resistance to antibiotics has developed over time to these bacterial pathogens, caution must be exercised in treatment, as overuse for systemic infections, in agriculture, sub-therapeutic doses and misuse for non-bacterial infections, remain problematic. Attractive novel modes of treatment that hold new promise for further investigation include lipid based therapy, as well as use of small molecules that bind deleterious specific host responsive molecules and use of microRNA based therapies. For bacterial and fungal pathogens, PACK-CXL potentially could become an alternative to standard antibiotic therapy for treatment of these corneal infections, reducing the global burden of microbial resistance to antibiotics and other therapeutic agents. For herpetic infections, instead of transplantation of whole corneas that are at high risk for failure, deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) to remove only inflamed corneal stroma and replacement of only that area may prove more clinically relevant.

23. Five-year view

Improved treatment for ocular bacterial and viral infections is anticipated based upon a plethora of excellent animal and clinical data that is expected to be refined and optimized for clinical efficacy over the next several years. More cautious use of antibiotics, curtailing their overuse systemically, as well as development of new therapies involving lipid based treatments, targeting of toxins, microRNA based therapeutics as well as use of small molecules that downregulate the host inflammatory response, especially to danger associated molecular pattern molecules, such as HMGB1, is anticipated. Therapeutically, alternative approaches to corticosteroid treatment, such as topical cyclosporine to manage ongoing HSK will be utilized. PACK-CXL (for bacterial) and DALK (for HSK) procedures will also potentially provide better management and outcome for keratitis patients.

24. Key Issues.

Antibiotic resistance and its consequences for treatment.

Rigorous studies on efficacy of PACK CXL needed.

New modes of treatment-how to get to clinical testing.

Targeting of microbial virulence factors-is it enough.

Targeting toxins-effectiveness of this approach.

Modulation of host immune response to better control bystander damage.

Immune response to HSV-angiogenesis and transplant of high risk corneas.

Treatment window clinically must be adequate for targeting of host response.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors were supported by NIH/NEI R01EY016058 and P30EY004068 grants and a 2012 Alcon Research award received by L. Hazlett. S. Suvas has received the grant NIH/NEI R01 R01EY022417. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

Papers of special note have been annotated as:

* Of interest

** Of considerable interest

- 1.Gaujoux T, Chatel MA, Chaumeil C, et al. Outbreak of contact lens-related Fusarium keratitis in France. Cornea. 2008;27:1018–1021. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318173144d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang DC, Grant GB, O’Donnell K, et al. Multistate outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solution. JAMA. 2006;296:953–963. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khor WB, Aung T, Saw SM, et al. An outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with contact lens wear in Singapore. JAMA. 2006;295:2867–2873. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.24.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imamura Y, Chandra J, Mukherjee PK, et al. Fusarium and Candida albicans biofilms on soft contact lenses: model development, influence of lens type, and susceptibility to lens care solutions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:171–182. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00387-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Meenakshi R, et al. Microbial keratitis in South India: influence of risk factors, climate, and geographical variation. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:61–69. doi: 10.1080/09286580601001347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Meenakshi R, et al. Analysis of the risk factors predisposing to fungal, bacterial and Acanthamoeba keratitis in south India. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:749–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie L, Zhong W, Shi W, Sun S. Spectrum of fungal keratitis in north China. Ophthalmol. 2006;113:1943–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Sun S, Jing Y, et al. Spectrum of fungal keratitis in central China. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37:763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira M, Ribeiro H, Delgado JL, et al. The effects of meteorological factors on airborne fungal spore concentration in two areas differing in urbanisation level. Int J Biometeorol. 2009;53:61–73. doi: 10.1007/s00484-008-0191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddiqui S, Anderson VL, Hilligoss DM, et al. Fulminant mulch pneumonitis: an emergency presentation of chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:673–681. doi: 10.1086/520985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martire B, Rondelli R, Soresina A, et al. Clinical features, long-term follow-up and outcome of a large cohort of patients with chronic granulomatous disease: an Italian multicenter study. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallien S, Fournier S, Porcher R, et al. Therapeutic outcome and prognostic factors of invasive aspergillosis in an infectious disease department: a review of 34 cases. Infection. 2008;36:533–538. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-7375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denning DW, Follansbee SE, Scolaro M, et al. Pulmonary aspergillosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:654–662. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103073241003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leal SM, Jr, Vareechon C, Cowden S, et al. Fungal antioxidant pathways promote survival against neutrophils during infection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2482–2498. doi: 10.1172/JCI63239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark HL, Jhingran A, Sun Y, et al. Zinc and manganese chelation by neutrophil S100A8/A9 (calprotectin) limits extracellular Aspergillus fumigatus hyphal growth and corneal infection. J Immunol. 2016;96:336–344. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *16.Leal SM, Jr, Roy S, Vareechon C, et al. Targeting iron acquisition blocks infection with the fungal pathogens Aspergillus fumigatus and Fusarium oxysporum. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(7):e1003436. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003436. Experimental novel finding showing targeting iron acquisition block infections with fungal pathogens. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor PR, Leal SM, Jr, Sun Y, et al. Aspergillus and Fusarium corneal infections are regulated by Th17 cells and IL-17 producing neutrophils. J Immunol. 2014;192(7):3319–3327. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karthikeyan RS, Leal SM, Jr, Prajna NV, et al. Expression of innate and adaptive immune mediators in human corneal tissue infected with Aspergillus or Fusarium. J Inf Dis. 2015;211:130–134. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Netea MG, Brown GD, Kullberg BJ, et al. An integrated model of the recognition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:67–78. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Netea MG, Gow NA, Munro CA, et al. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1642–1650. doi: 10.1172/JCI27114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jouault T, Ibata-Ombetta S, Takeuchi O, et al. Candida albicans phospholipomannan is sensed through Toll-like receptors. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:165–172. doi: 10.1086/375784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown GD, Herre J, Williams DL, et al. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of beta glucans. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1119–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Canavera SJ, et al. Collaborative induction of inflammatory responses by dectin-1 and Toll-like receptor 2. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1107–1117. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor PR, Tsoni SV, Willment JA, et al. Dectin-1 is required for beta-glucan recognition and control of fungal infection. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:31–38. doi: 10.1038/ni1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saijo S, Fujikado N, Furuta T, et al. Dectin-1 is required for host defense against Pneumocystis carinii but not against Candida albicans. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:39–46. doi: 10.1038/ni1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dennehy KM, Ferwerda G, Faro-Trindade I, et al. Syk kinase is required for collaborative cytokine production induced through Dectin-1 and Toll-like receptors. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:500–506. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gow NA, Netea MG, Munro CA, et al. Immune recognition of Candida albicans beta-glucan by dectin-1. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1565–1571. doi: 10.1086/523110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferwerda B, Ferwerda G, Plantinga TS, et al. Human dectin-1 deficiency and mucocutaneous fungal infections. N Eng J Med. 2009:1760–1767. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans DJ, Fleiszig SMJ. Microbial keratitis: could contact lens material affect disease pathogenesis? Eye Contact Lens. 2013;39(1):73–78. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e318275b473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Yu C, et al. Characterization of fusarium keratitis outbreak isolates: Contribution of biofilms to antimicrobial resistance and pathogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:4450–4457. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **31.FlorCruz NV, Evans JR. Medical interventions for fungal keratitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004241.pub4. Art. No.: CD004241. Review identified 12 randomised controlled trials that included 981 people; the evidence is current up to March 2015. The trials were mainly conducted in India and many were found to be underpowered. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandasana H, Prasad YD, Chhonker YS, et al. Corneal targeted nanoparticles for sustained natamycin delivery and their PK/PD indices: An approach to reduce dose and dosing frequency. Internl J Pharm. 2014;477:317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cope JR, Collier AS, Rao MM, et al. Contact lens wearer demographics and risk behaviors for contact lens-related eye infections-United States, 2014. CDC-MMWR. 2015;64(32):865–870. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6432a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouhenni R, Dunmire J, Rowe T, Bates J. Proteomics in the study of bacterial keratitis. Proteomes. 2015;3:496–511. doi: 10.3390/proteomes3040496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **35.Mah FS, Davidson R, Holland EJ, et al. Current knowledge about and recommendations for ocular methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40:1894–1908. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.09.023. Recommendations made based on evidence-based review to treat and possibly reduce the overall problem of this pathogen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *36.Chang VS, Dhaliwal DK, Raju L, Kowalski RP. Antibiotic resistance in the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus keratitis: a 20-year review. Cornea. 2015;34(6):698–703. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000431. Comparison of resistance patterns of methicillin resistant and/or susceptible S. aureus keratitis isolates with common topically applied ophthalmic antimicrobials. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhem MN, Lech EM, Patti JM, et al. The collagen-binding adhesion is a virulence factor in Staphylococcus aureus keratitis. Infect Immun. 2000;68(6):3776–3779. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3776-3779.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jett BD, Gilmore MS. Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by human corneal epithelial cells: role of bacterial fibronectin-binding proteins and host cell factors. Infect Immun. 2002;70(8):4697–4700. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4697-4700.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otto M. Staphylococcus aureus toxins. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014 Feb 01;:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Callaghan RJ, Callegan MC, Moreau JM, et al. Specific roles of alpha-toxin and beta-toxin during Staphylococcus aureus cornea infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65(5):1571–1578. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1571-1578.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inoshima I, Inoshima N, Wilke GA, et al. A Staphylococcus aureus pore-forming toxin subverts the activity of ADAM10 to cause lethal infection in mice. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1310–1314. doi: 10.1038/nm.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilke GA, Bubeck Wardenburg J. Role of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 in Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin-mediated cellular injury. PNAS. 2010;107(30):13473–13478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001815107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nygaard TK, Pallister KB, DuMont AL, et al. Alpha-toxin induces programmed cell death of human T cells, B cells, and monocytes during USA300 infection. PLos One. 2012;7(5):e36532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hume EBH, Cole N, Khan S, et al. A Staphylococcus aureus mouse keratitis topical infection model: cytokine balance in different strains of mice. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gokhale NS. Medical management approach to infectious keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:215–220. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.40360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Segreti J, Jones RN, Bertino JS. Challenges in assessing microbial susceptibility and predicting clinical response to newer-generation fluoroquinolones. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2012;28(1):3–11. doi: 10.1089/jop.2011.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, et al. Corticosteriods for bacterial keratitis: The steroids for corneal ulcers trial (SCUT) Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:143–150. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deschenes J, Blondeau J. Besifloxacin in the management of bacterial infections of the ocular surface. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015;50(3):184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vuong C, Yeh AJ, Cheung GTC, Otto M. Investigational drugs to treat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25(1):73–93. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2016.1109077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schechter BA, Parekh JG, Trattler W. Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0. 6% in the treatment of bacterial keratitis: a retrospective safety surveillance study. J Ocular Pharmacol Ther. 2015;31(2):114–121. doi: 10.1089/jop.2014.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chatterjee SS, Otto M. How can Staphylococcus aureus phenol-soluble modulins be targeted to inhibit infection? Future Microbiol. 2013;8(6):693–696. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laventie BJ, Rademaker HJ, Saleh M, et al. Heavy chain-only antibodies and tetravalent bispecific antibody neutralizing Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxins. PNAS. 2011;108(39):16404–16409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102265108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willcox MD. Management and treatment of contact lens-related Pseudomonas keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:919–924. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S25168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoge R, Pelzer A, Rosenau F, et al. Microbiology book series. Spain: Weapons of a pathogen: proteases and their role in virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa; pp. 383–395. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hazlett LD. Corneal response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004;23:1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eby AM, Hazlett LD. Pseudomonas keratitis, a review of where we’ve been and what lies ahead. J Microb Biochem Technol. 2015;7:453–457. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun Y, Karmakar M, Taylor PR, et al. ExoS and ExoT ADP ribosyltransferase activities mediate Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis by promoting neutrophil apoptosis and bacterial survival. J Immunol. 2012;188:1884–1895. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pearlman E, Sun Y, Roy S, et al. Host defense at the ocular surface. Int Rev Immunol. 2013;32:4–18. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.749400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berger EA, McClellan SA, Vistisen KS, Hazlett LD. HIF-1alpha is essential for effective PMN bacterial killing, antimicrobial peptide production and apoptosis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003457. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suryawanshi A, Cao Z, Thitiprasert T, et al. Galectin-1-mediated suppression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced corneal immunopathology. J Immunol. 2013;190:6397–6409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Foldenauer ME, McClellan SA, Berger EA, Hazlett LD. Mammalian target of rapamycin regulates IL-10 and resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infection. J Immunol. 2013;190:5649–5658. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solanki S, Rathi M, Khanduja S, et al. Recent trends: Medical management of infectious keratitis. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2015;8:83–85. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.159104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Breidenstein EB, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Hancock RE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fernandes M, Vira D, Medikonda R, et al. Extensively and pan-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis: clinical features, risk factors, and outcome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;254:315–322. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharma N, Jindal A, Bali SJ, et al. Recalcitrant Pseudomonas keratitis after epipolis laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Optom. 2012;95:460–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2012.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tallab RT, Stone DU. Corticosteroids as a therapy for bacterial keratitis: an evidence-based review of ‘who, when and why’. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307955. published online 7 january 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sy A, Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis: outcomes and response to corticosteroid treatment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:267–272. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borkar DS, Fleiszig SM, Leong C, et al. Association between cytotoxic and invasive Pseudomonas aeruginosa and clinical outcomes in bacterial keratitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:147–153. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ni N, Srinivasan M, McLeod SD, Acharya NR, Lietman TM, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Use of adjunctive topical corticosteroids in bacterial keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016 doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000273. published online 19 April 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brandt CR. Peptide therapeutics for treating ocular surface infections. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2014;30:691–699. doi: 10.1089/jop.2014.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu M, McClellan SA, Barrett RP, et al. Beta-defensins 2 and 3 together promote resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. J Immunol. 2009;183:8054–8060. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Szliter E, Lighvani S, Barrett RP, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide balances pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected cornea and protects against corneal perforation. J Immunol. 2007;178:1105–1114. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li SA, Liu J, Xiang Y, et al. Therapeutic potential of the antimicrobial peptide OH-CATH30 for antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3144–3150. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00095-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McClellan SA, Ekanayaka SA, Li C, et al. Thrombomodulin protects against bacterial keratitis, is anti-Inflammatory, but not angiogenic. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:8091–8100. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lim A, Wenk MR, Tong L. Lipid-based therapy for ocular surface inflammation and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:736–748. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *76.Lee JE, Sun Y, Gjorstrup P, et al. Inhibition of corneal inflammation by the resolvin E1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:2728–2736. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15982. Found that resolvin E1 blocked P. aeruginosa and S. aureus corneal inflammation either alone or with antibiotics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sun Y, Pearlman E. Inhibition of corneal inflammation by the TLR4 antagonist Eritoran tetrasodium (E5564) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1247–1254. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *78.McClellan S, Jiang X, Barrett R, et al. High-mobility group box 1: a novel target for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. J Immunol. 2015;94:1776–1787. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401684. First experimental report on HMGB1 in P. aeruginosa keratitis (clinical isolate and laboratory strain) identifying reduction of this molecule as clinically attractive. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang K, Wu M, Li M, et al. miR-155 suppresses bacterial clearance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced keratitis by targeting Rheb. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:89–98. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lumayag S, Haldin CE, Corbett NJ, et al. Inactivation of the microRNA-183/96/182 cluster results in syndromic retinal degeneration. PNAS. 2013;110(6):e507–516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212655110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Muraleedharan CK, McClellan SA, Barrett RP, et al. Inactivation of the miR-183/96/182 cluster decreases the severity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:1506–1517. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tabibian D, Richoz O, Hafezi F. PACK-CXL: Corneal cross-linking for treatment of infectious keratitis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2015;10:77–80. doi: 10.4103/2008-322X.156122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tabibian D, Mazzota C, Hafezi F. PACK-CXL: Corneal cross-linking in infectious keratitis. Eye Vis (London) 2016;19:3–11. doi: 10.1186/s40662-016-0042-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tal K, Gal-Or O, Pillar S, et al. Efficacy of Primary Collagen Cross-Linking with Photoactivated Chromophore (PACK-CXL) for the Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus-Induced Corneal Ulcers. Cornea. 2015;34(10):1281–1286. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bamdad S, Malekhosseini H, Khosravi A. Ultraviolet A/riboflavin collagen cross-linking for treatment of moderate bacterial corneal ulcers. Cornea. 2015;34(4):402–406. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **86.Chan TCY, Lau TWS, Lee JWY, et al. Corneal collagen cross-linking for infectious keratitis: an update of clinical studies. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2015;93:689–696. doi: 10.1111/aos.12754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Young RC, Hodge DO, Liesegang TJ, Baratz KH. Incidence, recurrence, and outcomes of herpes simplex virus eye disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–2007: the effect of oral antiviral prophylaxis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(9):1178–1183. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shimeld C, Hill TJ, Blyth WA, Easty DL. Reactivation of latent infection and induction of recurrent herpetic eye disease in mice. J Gen Virol. 1990;71(Pt 2):397–404. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-2-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liesegang TJ. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis and anterior uveitis. Cornea. 1999;18(2):127–143. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Colin J. Ganciclovir ophthalmic gel, 0. 15%: a valuable tool for treating ocular herpes. Clin Ophthalmol. 2007;1(4):441–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Holland EJ, Schwartz GS. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea. 1999;18(2):144–154. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199903000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Barron BA, Gee L, Hauck WW, et al. Herpetic Eye Disease Study. A controlled trial of oral acyclovir for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(12):1871–1882. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(13)31155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]