Abstract

Future perspectives of transgender youth and their caregivers may be shaped by knowledge of discrimination and adverse mental health among transgender adults. Qualitative data from the Trans Youth Family Study were used to examine how transgender and gender nonconforming (TGN) youth and their caregivers imagine the youth's future. A community-based sample of 16 families (16 TGN youth, ages 7-18 years, and 29 caregivers) was recruited from two regions in the United States. Participants completed in-person qualitative interviews and surveys. Interview transcripts were analyzed using grounded theory methodology for coding procedures. Analyses yielded 104 higher order themes across 45 interviews, with eight prominent themes: comparing experiences with others, gender affirming hormones, gender affirming surgery, gender norms, questioning whether the youth is really transgender, expectations for romantic relationships, uncertainty about the future, and worries about physical and emotional safety. A conceptual model of future perspectives in TGN youth and caregivers is presented and clinical implications are discussed.

Keywords: transgender youth, gender identity, family, parent-child relationships, future orientation

As the field of psychology as a whole has moved from pathologizing transgender individuals (Drescher, 2010), toward affirming and understanding their experiences, counseling psychology has played a critical role in guiding clinical service provision and conducting research, which affirms transgender identities. Transgender and gender nonconforming (TGN) individuals have a different gender identity and/or expression than their sex assigned at birth. “Transgender” is generally conceptualized as an umbrella term that encompasses a number of diverse gender identities including: genderqueer, trans woman, trans man, agender, and transsexual, amongst a host of other terms (Davidson, 2007). Conversely, the term “cisgender” is used to describe individuals for whom their gender identity is aligned with their sex assigned at birth.

The literature on transgender individuals has grown extensively and rapidly in recent years, with the experiences of transgender youth and their families in particular obtaining more specific attention. A great deal has been learned about psychological and medical service provision to transgender youth and their families (e.g., Coolhart, Baker, Farmer, Malaney, & Shipman, 2013; Edwards-Leeper & Spack, 2012; Vance, Halpern-Felsher, & Rosenthal, 2015), barriers to appropriate care for transgender youth (Gridley et al., 2016; Vance et al., 2015), discrimination and stigma faced by transgender youth (e.g., Ignatavicius, 2013; McGuire, Anderson, Toomey, & Russel, 2010; Veale et al., 2015), the important role family support plays in supporting the psychological well-being of transgender youth (Simons, Schrager, Clark, Belzer, & Olson, 2013; Travers et al., 2012; Veale et al., 2015), and the identity processes and resilience of transgender youth (e.g., Difulvio, 2015; Grossman, D'Augelli, & Frank, 2011; Pollock & Eyre, 2012; Singh, Meng, Hansen, 2014; Testa, Jimenez, & Rankin, 2014).

Although recent scholarship has begun to provide a better understanding of the experiences and needs of transgender youth and their families, there is still much work that needs to be done. In particular, there is a very limited understanding of how transgender youth and their families conceptualize the future of transgender youth. Although some studies of transgender youth have investigated important contributors to future orientation or future perspectives (i.e., how people think about the future), such as the broader social context and the more proximate family system, no study has explicitly examined the future perspectives of transgender youth and their families. The aim of this exploratory qualitative study was to examine transgender and gender nonconforming (TGN) youths’ and caregivers’ perceptions of the youth's future in light of the youth's gender identity, and in turn, use this data to inform counseling interventions.

Future Perspectives

Future perspectives can be defined as “the images humans develop regarding the future, as consciously represented and self-reported” (Seginer, 2009, p. 3). In taking a thematic approach to understanding future perspectives, reviews of the literature (Massey, Gebhardt, & Garnefski, 2008, Nurmi, 1991, Seginer, 2009) have found that six life domains tend to predominate the future orientation of youth: education, work and career, marriage and family, self-concerns (i.e., general images of the self, mood states, and personality characteristics), others (i.e., general images of other individuals like friends and family), and collective issues (i.e., images of society, one's community, one's nation, and the world). However, the specific content of future perspectives and other life domains that might be salient for youth may vary greatly depending on social and familial contextual factors, such as the beliefs, values, norms, and living conditions youth experience. Future perspectives across life domains tend to reflect major developmental tasks of adolescence and early adulthood and manifest through hopes, goals, and expectations (e.g., wanting to pursue a particular job or career, hoping to be happy or courageous), as well as fears and concerns (e.g., fearing failure at school or future divorce).

In a study focused exclusively on caregivers of transgender youth, caregivers expressed fears for their children's safety, happiness, and adjustment (Hill & Menvielle, 2009). Given that parental beliefs and future perspectives have been shown to influence how cisgender adolescents think about their future (Seginer & Mahajna, in press; Seginer & Shoyer, 2012), it may be that these fears also influence the future perspectives of transgender youth. Among transgender adults, future perspectives have been investigated in the form of anticipated stigma (Golub & Gamarel, 2013) and potentially traumatic events (Shipherd, Maguen, Skidmore, & Abramovitz, 2011); however, these studies are focused on specific aspects of future perspectives and are limited to specific populations in the transgender community. No studies have explicitly sought to understand how both transgender youth and caregivers conceptualize their futures across various life domains.

Among cisgender adolescents, future perspectives are associated with various life outcomes, including: academic achievement (Scholtens, Rydell, & Yang-Wallentin, 2013); violent behaviors (Stoddard, Zimmerman, & Bauermeister, 2011); identity formation (Sharp & Coatsworth, 2012); and adult alcohol use, civic behaviors, and social roles (Finlay et al., 2015). Future perspectives have also been shown to explain the association between traumatic events and depression, loneliness, and self-esteem among youth (Zhang et al., 2009). Among young adults, future thinking partially explains the association between suicide motivation and depressive symptoms and the association between suicide motivation and hopelessness (Chin & Holden, 2013). Additionally, parental support and acceptance are associated with cisgender youth having positive expectations and a greater sense of personal control over the future (Lanz & Rosnati, 2002; Pulkkinen, 1990; Seginer, Vermulst, & Shoyer, 2004). Although no studies have explicitly examined the future perspectives of transgender youth, the social and family contexts which influence the development of future orientation (Massey et al., 2008; Nurmi, 1991, Seginer, 2009), have received attention in the literature.

Social Context, Discrimination, and Mental Health

In the United States, when people exhibit behaviors or present themselves in ways that do not conform to the gender norms associated with their sex assigned at birth (i.e., are gender nonconforming) they are likely to experience negative repercussions for the violation of those gender norms (Ohbuchi et al., 2004). The U.S. National Transgender Discrimination Survey, which sampled nearly 6,500 transgender adults, found that 12% of participants who expressed their transgender identity or exhibited gender nonconformity in grades K-12 reported being sexually assaulted by another student, a teacher, or a staff member; and 35% reported being physically assaulted and 78% reported experiencing harassment (Grant et al., 2011). The Canadian Trans Youth Health Survey found that two thirds of the 923 youth surveyed reported discrimination based on their gender identity, 70% had experienced sexual harassment, and 36% were physically threatened or injured during the last year (Veal et al., 2015).

In addition to discrimination and victimization, transgender individuals face alarming rates of adverse mental health outcomes, including suicide attempts reported by 41% of transgender adults (Grant et al., 2011); rates of depression ranging from 44-65%, and rates of anxiety ranging from 33-45% (Bockting, et al., 2013; Budge, Adelson, & Howard, 2013, Tebbe & Moradi, 2016). These rates are substantially higher than the general U.S. adult population, in which 4.6% of adults report attempting suicide (Nock, Hwang, Sampson, & Kessler, 2006), 6.7% of adults report having at least one major depressive episode over a 12 month period, and 11.1% report a diagnosable anxiety disorder over a 12 month period (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). In a study of youth who receive care from an urban clinic, transgender youth were found to be at two to three times higher risk than matched cisgender controls for non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, depression, and anxiety (Reisner et al., 2015). Minority stress theory postulates that stigma, victimization, and other forms of discrimination experienced by TGN people are the primary contributors to adverse mental health outcomes in this population (Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Meyer, 2003). Therefore, the high rates of suicide attempts, depression, and anxiety among transgender people result from the adversity transgender people face.

The disparities seen across mental health outcomes may themselves reveal aspects of future perspectives expressed by some transgender youth. Suicide and suicidal behaviors have demonstrated a consistent relationship to hopelessness (Klonsky, May, & Saffer, 2016), which itself represents negative expectancies about the future (Beck, 1974). Negative views about the future are also one component of the cognitive triad formulated by Beck to conceptualize depression (Beck, 1976), and anxiety itself is characterized by worry or “apprehensive expectation” over the future (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The social context of discrimination and victimization experienced by transgender youth and the resultant minority stress they experience could therefore lead to fears, concerns, and negative views of the future, which may then lead to the mental health disparities that have been observed.

Although these disparities indicate a need for mental health services, an important aspect of the social context for transgender youths’ lives is the presence of significant barriers to accessing gender-affirmative mental and physical healthcare in the United States. Transgender youth and their caregivers have identified a number of these barriers, including: a lack of accessible healthcare providers who work with children and have training in gender affirming care; a lack of consistency in protocol use; use of incorrect names or pronouns; gatekeeping and lack of coordinated care; delayed or limited access to pubertal blocking medications and hormones; and exclusion from insurance policies (Gridley, et al., 2016). Healthcare providers themselves have identified a lack of training, limited to no exposure to transgender patients, lack of qualified mental health clinicians, and difficulty obtaining insurance reimbursement for transgender-related care (Vance et al., 2015). Without appropriate access to care, transgender youth may have difficulty realizing the future they see for themselves and these barriers likely influence the hopes, goals, expectations, fears, and concerns they have related to their futures.

Family Support

Although transgender individuals are disproportionately subject to adversity, transgender youth who receive higher levels of support from their families have been shown to experience better mental health outcomes, including: lower likelihood of engaging in non-suicidal self-injury, lower rates of suicidal ideation, fewer suicide attempts, fewer depressive symptoms, a decreased sense of burdensomeness stemming from the youth's transgender identity, higher self-esteem, and higher levels of life satisfaction (Simons, et al., 2013; Travers et al., 2012; Veale et al., 2015). Although family support may play a critical role in sustaining the mental health and well-being of transgender youth, few studies have examined the experiences of caregivers of transgender youth. Caregivers may have a range of reactions when they first learn about their transgender youth's gender identity including surprise, feeling a sense of loss, supporting the youth with love, viewing their youth's gender-nonconformity as a phase, seeing the youth's gender identity as a symptom of a resolvable psychological issue, psychologically abusing the youth, or physically abusing the youth (Grossman, D'Augelli, Howell, & Hubbard, 2005; Tishelman, Kaufman, Edwards-Leeper, Mandel, Shumer, & Spack, 2015). Some of these reactions may be associated with how caregivers see the future of their transgender child and the way transgender youth see their own future.

Current Study

Given the influence of social and familial contextual factors on future orientation, the unique social context of transgender youth, the importance of family support to the well-being of transgender youth, and the relationship between future orientation and various outcomes related to mental health that have been found among cisgender youth, the aim of the current exploratory study was to examine how TGN youth and their caregivers perceive the youth's future in light of the youth's transgender identity. Specifically, the study sought to answer the following research questions: 1) What are the primary themes and life domains around which TGN youth and their families focus their future perspectives, 2) How does the unique social context of TGN youth influence the way TGN youth and their caregivers think about the youth's future? and 3) How might the themes and life domains of future perspectives identified by TGN youth and their caregivers relate to one another? Qualitative data were analyzed from TGN youth and caregiver interviews from the Trans Youth Family Study, a multi-site mixed methods study of families with TGN youth.

Method

Participants

Participants were 16 families, including 16 TGN youth, ages 7-18 years (M = 12.55, SD = 3.86), and 29 cisgender (non-transgender) caregivers (Total individual N = 45). Youth self-identified their current gender identity as trans boy (n = 9), trans girl (n = 5), gender fluid boy (n = 1), and girlish boy (n = 1). Caregivers included mothers (n = 17), fathers (n = 11), and one grandparent. Other sample demographics are reported in Table 1. Participants were recruited from lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community organizations and support networks for families with transgender youth in New England and the lower Midwestern United States, as well as via snowball sampling. Youth were eligible to participate in the study if they were age 5-18 years and identified with a different gender from their assigned birth sex (e.g., transgender, trans) or were gender nonconforming. Caregivers were eligible to participate if they had a youth who met the above criteria. Youth and at least one caregiver were required to participate in the study together. Volunteers were asked to participate in a study about the experiences of transgender youth and their caregivers, including emotional experiences and perceptions of the youth's gender identity.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics for Transgender Youth and Caregivers from the Trans Youth Family Study

| Measure | Youth (N = 16) | Caregivers (N = 29) | Families (N = 16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M (SD) | 12.55 (3.86) | 47.45 (7.06) | |

| Sex assigned at birth, % (n) | |||

| Female | 56.3 (9) | 62.1 (18) | |

| Male | 43.8 (7) | 37.9 (11) | |

| Current gender identity, % (n) | |||

| Cisgender woman | 62.1 (18) | ||

| Cisgender man | 37.9 (11) | ||

| Trans girl/girl | 31.3 (5) | ||

| Trans boy/boy | 56.3 (9) | ||

| Other | 12.5 (2) | ||

| Race/ethnicity, % (n) | |||

| White | 87.5 (14) | 75.9 (22) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3.4 (1) | ||

| Multiracial/other | 12.5 (2) | 20.7 (6) | |

| Education, % (n) | |||

| High school diploma/GED | 3.4 (1) | ||

| Some college | 6.9 (2) | ||

| College degree | 48.3 (14) | ||

| Graduate degree | 41.4 (12) | ||

| Individual income, % (n) | |||

| $10,000-30,000 | 10.3 (3) | ||

| $30,001-60,000 | 24.1 (7) | ||

| $60,001-100,000 | 24.1 (7) | ||

| ≥ $100,001 | 37.9 (11) | ||

| Retired | 3.4 (1) | ||

| County of origin, % (n) | |||

| U.S. | 89.7 (26) | ||

| Non-U.S. | 10.3 (3) | ||

| Current geographic location, % (n) | |||

| New England | 81.3 (13) | ||

| Midwest | 18.8 (3) | ||

| Sexual orientation, % (n) | |||

| Heterosexual/straight | 31.3 (5) | 82.8 (24) | |

| Bisexual | 12.5 (2) | 6.9 (2) | |

| Lesbian/gay | 6.3 (1) | 6.9 (2) | |

| Pansexual | 6.3 91) | ||

| Unsure | 43.8 (7) | ||

| Other | 3.4 (1) | ||

| Relationship status, % (n) | |||

| Single | 3.4 (1) | ||

| Married | 79.3 (23) | ||

| Living with partner (unmarried) | 6.9 (2) | ||

| Separated/divorced | 10.3 (3) | ||

| Widowed | 3.4 (1) |

Notes. Caregiver age range: 34-63 years. Youth age range: 7-18 years. All cisgender men were fathers. 17 out of 18 cisgender women were mothers; 1 was a grandmother. Other gender identities included gender-variant and “girlish boy.” Frequencies for languages used at home, religion practiced at home, and relationship status were overlapping because participants could choose or write in more than one option.

Researchers

The authors of this study represented a diversity of perspectives stemming from varying life experiences related to holding different social positions and identities. Katz-Wise is a White queer (non-heterosexual) cisgender female research scientist and instructor who is trained in developmental psychology, gender and women's studies, and social epidemiology and has expertise in research with transgender youth and families. Budge is a White queer (non-heterosexual) female professor of counseling psychology with expertise in research with transgender populations. Katz-Wise and Budge are co-Principal Investigators of this study. Orovecz is a White gay male doctoral student in counseling psychology and focuses his work on LGBTQ issues and crisis and suicide prevention and intervention. Nguyen is a Vietnamese-American gay male medical student. Nava-Coulter is a bi-racial queer graduate student in sociology, whose work focuses on gender and sexuality. Finally, Thomson is a White queer (non-heterosexual) cisgender clinical child and adolescent psychologist. The first five authors were interviewers and Thomson was part of the on-call mental health team for the study. Katz-Wise, Nguyen, and Nava-Coulter completed the data analysis and Katz-Wise, Budge, Nguyen, and Nava-Coulter participated in formulating a conceptual model from the themes identified during analysis. Other members of the research team who assisted in conducting and transcribing interviews were graduate students in counseling psychology, clinical psychology, public health, and human development.

When we began this analysis, we were unable to locate any previous literature that had examined future perspectives in families with transgender youth. Therefore, our assumptions were largely based on team members’ previous experiences with transgender research and the general impressions of the team members based on conducting interviews for the study. We began with the assumption that exposure to adverse outcomes (e.g., discrimination, mental health issues) experienced by transgender individuals in the media and outside of the participants’ families would shape participants’ thoughts about the youth's future as it relates to their gender identity. We expected caregivers to be more future-orientated than youth and to have a more negative outlook of the youth's future than the youth themselves. Finally, we expected that participants’ future perspectives might differ based on the age of the youth, how much time had passed since the youth came out as transgender, and how their coming out was received by family and friends.

Measures

The interview protocols for TGN youth and caregivers were semi-structured and developed for the current study. Separate developmentally appropriate interview protocols were developed for TGN youth age 5-11 years, TGN youth age 12-18 years, and caregivers. Interview questions addressed perceptions of the youth's gender identity development, emotions and coping related to the youth's gender identity, effects of the youth's gender identity on relationships within and outside of the family, and support needs. The primary interview questions of interest for the current study assessed effects of the youth's gender identity on the youth's future; however, each transcript was analyzed as a whole for themes related to future perspectives. Caregivers were asked to “Describe the future that you imagine for your child, considering their gender identity” with the following probes: “How do you think your child's gender identity might affect their future?” and “How has your thinking about this changed compared to when you first learned about your child's gender identity?” Youth age 5-11 years were asked “When you grow up, how do you think your life might be different from your friends?” and youth age 12-18 years were asked “How do you think your transgender identity will affect your future?” If youth age 5-11 years did not mention their gender identity, they were probed regarding whether they thought their life might be different based on their current gender identity.

Procedure

Study sessions were conducted between April and October 2013 in participants’ homes or at the researchers’ institutions. All participants gave informed assent/consent prior to participating. Study sessions lasted approximately two hours and consisted of one-on-one in-person semi-structured qualitative interviews with each family member in separate rooms, followed by completion of a short quantitative survey. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by graduate students from the researchers’ institutions. Participants were not offered compensation for participating in this study due to funding constraints. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each study site.

Analytic Methodology

Interview transcripts were analyzed by Katz-Wise, Nguyen, and Nava-Coulter using grounded theory methodology for the coding procedures (Charmaz, 2014). Data from youth and caregivers were combined because the interview protocols for the two types of participants contained parallel questions that yielded similar content and themes. Prior to beginning the coding procedures, the coders met to discuss and document their biases and assumptions. These notes were revisited throughout the analytic phases, as well as during the writing of this report. First, two coders completed initial (line by line) coding separately for each transcript and came to consensus, during which any discrepancies in the coding were discussed and resolved. During this phase, lines from the transcript were coded into more concise statements. Second, two coders completed focused coding, in which line by line codes were categorized into higher order codes by consensus. Line by line codes could be categorized into more than one higher order code. The first two phases were completed for each transcript prior to moving on to the next transcript to allow for constant comparison. Higher order codes were created across all participants without regard to participant type (e.g., youth vs. caregivers, mothers vs. fathers). Third, all members of the research team completed the theoretical coding phase. In this phase, higher order codes were placed into broader themes and a conceptual model was generated to describe the phenomenon of perspectives of TGN youths’ futures. Prior to theoretical coding, Budge audited the results of the first two coding phases by reviewing the categorization of line by line codes into higher order codes.

Results

Conceptualizations of Future Perspectives

Future perspectives have been defined rather broadly as images of the future that are “consciously represented and self-reported” (Seginer, 2009, p. 3), without reference to the timeframe of future. In the current study, we identified three different conceptualizations of future perspectives: 1) past conceptualizations of the future, 2) conceptualizations of the short-term future, and 3) conceptualizations of the long-term future. Past conceptualizations of the future were present in participants’ narratives when they reflected on how they thought about the future at an earlier time. For instance, caregivers of older TGN youth talked about when their child first came out as transgender and how they anticipated their child's future at that point. This was often contrasted with feeling differently about the youth's future now that the youth was older. Conceptualizations of the short-term future were present in participants’ narratives when they expressed concerns related to the youth's immediate future, such as worries related to summer camp or school in the weeks or months following the interview. Finally, conceptualizations of the long-term future were present in participants’ narratives when they expressed concerns related to the youth's individual long-term future and/or the long-term future of the larger society, such as discussions of college for younger youth, or marriage for youth of any age. The long-term future of the larger society was described in thinking about acceptance of TGN individuals and transgender rights. The classification of short-term vs. long-term future was interpreted on an individual participant basis, as short-term and long-term may be different for TGN youth of different ages or at different stages of transgender identity development.

Conceptual Model of Future Perspectives

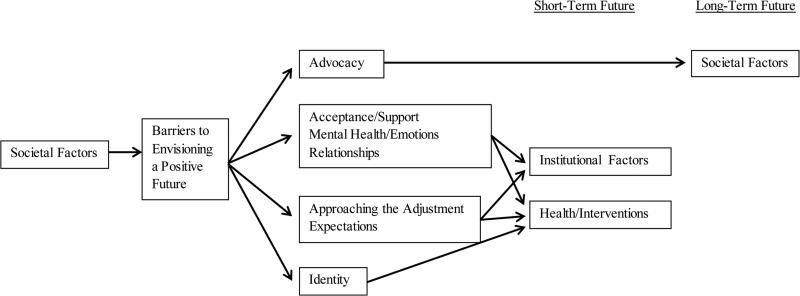

We identified 104 higher order themes overall across the 45 interviews. The full list of higher order codes, the number of line by line codes within each code by type of participant (youth vs. caregiver), and the broader theme in which each code was placed is shown in Table 2. Below we describe higher order codes in the model that were considered prominent, as represented by 20 or more line by line codes. When there was more than one prominent code, we describe a subset of the codes. The higher order codes were categorized into broader themes, which were organized into a conceptual model of future perspectives (Figure 1). In the model, themes represent a primarily linear process, with interplay among different contextual factors. Societal factors appear on the left-hand and right-hand side of the model to represent the beginning and end of the process. These types of factors were experiences that represented societal-level institutions (e.g., religion), social constructs (e.g., gender norms), and societal attitudes toward TGN individuals. Moving from left to right in the model, societal factors created barriers to envisioning a positive future for families with TGN youth, such as anticipating experiences of discrimination and rejection. These barriers then influenced a number of other experiences, which were grouped into four categories: 1) advocacy; 2) acceptance/support, mental health/emotions, relationships; 3) approaching the adjustment, expectations; and 4) identity. Categories 2 and 3 combined multiple larger themes because they were thematically related. Continuing to move toward the right-hand side of the model, these experiences then informed institutional factors (e.g., school, employment) and health/interventions in the individual youth's short-term future and society's long-term future.

Table 2.

Higher Order Themes and Number of Line By Line Codes

| Category | Higher Order Theme | Total Line by Line Codes | Line by Line Codes from Caregiver Interviews | Line by Line Codes from Youth Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Societal Factors | Comparing experiences | 60 | 53 | 7 |

| Gender norms | 43 | 42 | 1 | |

| Passing | 19 | 11 | 8 | |

| Societal views of LGBTQ issues | 11 | 8 | 3 | |

| Fitting in | 9 | 8 | 1 | |

| Social interactions | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Living as identified gender will be easier | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Religion | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Barriers to envisioning a positive future | Discrimination | 27 | 24 | 3 |

| Policies and rights | 23 | 21 | 2 | |

| Insurance and finances | 21 | 17 | 4 | |

| Romantic relationships – concerns | 18 | 15 | 3 | |

| Rejection | 17 | 14 | 3 | |

| Discrimination – bullying | 14 | 14 | 0 | |

| Discrimination – employment | 11 | 7 | 4 | |

| Legal issues (e.g., official documents) | 10 | 7 | 3 | |

| Perceived as unusual | 7 | 7 | 0 | |

| Barriers to gender affirming treatment | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Attractiveness | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Difficulty imagining youth's future | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Advocacy | Activism | 25 | 23 | 2 |

| Knowledge/education about transgender | 14 | 14 | 0 | |

| Helping others | 12 | 11 | 1 | |

| Acceptance/support | Supportive communities – youth | 31 | 28 | 3 |

| Supportive communities – caregivers/family | 27 | 27 | 0 | |

| Being a good caregiver | 26 | 26 | 0 | |

| Wanting the best for youth | 25 | 25 | 0 | |

| Acceptance-interpersonal | 24 | 21 | 3 | |

| Acceptance-broad | 21 | 16 | 5 | |

| Being a good caregiver – support | 18 | 18 | 0 | |

| Being a good caregiver – skills & preparation | 15 | 15 | 0 | |

| Being a good caregiver – protection | 10 | 10 | 0 | |

| Seeking support/resources | 9 | 8 | 1 | |

| Mental health/emotions | Worry about safety – physical and emotional | 48 | 46 | 2 |

| Emotions – fear | 34 | 34 | 0 | |

| General worry about future | 31 | 30 | 1 | |

| Mental health – happiness | 22 | 21 | 1 | |

| Emotions – positive | 16 | 15 | 1 | |

| Mental health | 15 | 14 | 1 | |

| Emotions – sadness/grief | 14 | 14 | 0 | |

| Emotions – anxiety | 13 | 13 | 0 | |

| Reassurance | 12 | 12 | 0 | |

| Comfort with body | 11 | 11 | 0 | |

| Emotions – hardship | 10 | 10 | 0 | |

| Mental health – suicidality | 7 | 7 | 0 | |

| Relationships | Friendships | 24 | 18 | 6 |

| Caregiver-child relationship | 22 | 19 | 3 | |

| Caregiver discordance or agreement | 17 | 17 | 0 | |

| Relationships with extended family | 14 | 14 | 0 | |

| Parent-parent relationship | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Effect of having transgender sibling | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Approaching the adjustment | Uncertainty about the future | 39 | 34 | 5 |

| Is my child really transgender? | 36 | 34 | 2 | |

| Planning/preparation | 34 | 30 | 4 | |

| Decision-making about being out | 28 | 12 | 16 | |

| Desire for certainty | 14 | 14 | 0 | |

| Perseverance/determination | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Avoidance of thinking about youth's future | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Going with the flow/being flexible | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Origin of being transgender | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Expectations | Romantic relationships – expectations | 35 | 23 | 12 |

| Expectations about coming out | 31 | 20 | 11 | |

| Self-sufficiency | 30 | 30 | 0 | |

| Ideal expectations for youth's future | 29 | 24 | 5 | |

| Societal views of LGBTQ issues – hopes for future | 27 | 25 | 2 | |

| General expectations about youth's/family's future | 23 | 20 | 3 | |

| Youth's future family | 23 | 21 | 2 | |

| Difficult future/challenges | 19 | 18 | 1 | |

| Normative expectations | 15 | 15 | 0 | |

| Sexual orientation – caregiver expectations | 15 | 15 | 0 | |

| Change in expectations | 13 | 12 | 1 | |

| Reproduction | 10 | 9 | 1 | |

| Positive effects of being transgender | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Transgender identity won't affect future | 6 | 1 | 5 | |

| Sexual activity | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Identity | Authenticity | 28 | 27 | 1 |

| Personality and behavior | 23 | 23 | 0 | |

| Desire to be another gender | 19 | 18 | 1 | |

| Names | 17 | 14 | 3 | |

| Transition process | 17 | 13 | 4 | |

| Sexual orientation – youth self-identification | 10 | 6 | 4 | |

| Emphasis on youth's transgender identity | 8 | 3 | 5 | |

| Genitals | 8 | 8 | 0 | |

| Self-fulfillment | 8 | 8 | 0 | |

| Fluidity of transgender identity | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Gender spectrum/genderqueer | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Maintaining attributes | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Institutional factors | Camp | 34 | 27 | 7 |

| School – pre-college | 32 | 26 | 6 | |

| Employment/career – youth, specific careers | 30 | 14 | 16 | |

| Employment/career – youth, work issues | 28 | 16 | 12 | |

| College | 14 | 11 | ||

| Changing schools/moving cities | 13 | 9 | 4 | |

| Facilities (e.g., bathroom) | 12 | 9 | 3 | |

| Employment/career – caregiver | 10 | 10 | 0 | |

| College – housing | 7 | 7 | 0 | |

| Health/Interventions | Gender affirming treatment – hormones | 45 | 42 | 3 |

| Gender affirming treatment – surgery | 37 | 27 | 10 | |

| Gender affirming treatment – feelings | 32 | 30 | 2 | |

| Professional help | 30 | 27 | 3 | |

| Gender affirming treatment | 13 | 12 | 1 | |

| Puberty | 9 | 9 | 0 | |

| Health | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

Figure.

Conceptual model of transgender youths’ and caregivers’ future perspectives.

Societal Factors

As described above in the conceptual model, societal factors first influenced barriers to envisioning a positive future and then affected perceptions of the long-term future. The two most prominent higher order codes (represented by 20 or more line by line codes) in societal factors were comparing experiences with others and gender norms. In imagining the youth's future, participants compared the youth's experiences with other TGN youth and adults, cisgender youth, and lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) individuals. One youth participant compared himself with other TGN individuals when describing his short-term future: “...a lot of people, [being transgender] sort of affects their future. I haven't really let it affect my future. I still get good grades; I've graduated with honors, I'm going to a good university...” (Trans boy, age 18 years).

For some caregivers, meeting or talking to TGN adults gave them perspective on their child's long-term future. A mother of a trans boy, age 18 years, described talking to a trans man about his experience,

I said ‘Listen, thank you for talking to me. I really want to ask you some invasive questions, because I need to understand what is coming down the road for us. I need to know your journey so that I can understand what ours might be.’

At times, talking to a TGN adult was reassuring to caregivers, as in the narrative of a father of a trans boy, age 15 years,

...just to meet a happy, healthy, well-adjusted male and to see that [child] could end up being a happy, healthy, well-adjusted male was like such an amazing relief...I think that helped so much. Just that this doesn't have to be a freak show. It doesn't have to be bizarre. This doesn't have to be, you know, somebody with tattoos all over their body...this can just be a happy, healthy, well-adjusted male child.

Gender norms was a prominent code within the broader theme of societal factors that included appearance (e.g., body size, clothing, hair length and style), personality and behavior (e.g., being sensitive), interests (e.g., sports), and gender roles (e.g., careers). In one parent's past conceptualization of the future, she described concern about her child's future romantic relationships due to his body size being atypical for a male, “I used to worry in the beginning...he's so small, whose gonna love him? I worried about his physical size...I worried that that would hold him back from having a future with somebody” (Mother of a trans boy, age 18 years). An 8-year-old youth participant who identified as a “girlish boy” similarly worried about other people's reactions related to gender norms in the long-term future, as told by his mother,

He said [to me], ‘But I'm not going to get married, because if I married a boy I'd want to be the bride...I would want to wear a dress and people would laugh at me because I'm marrying a boy and I'd be wearing a dress.

Barriers to envisioning a positive future

Societal factors produced barriers to envisioning a positive future for families with TGN youth. Barriers included prominent higher order codes such as: general discrimination, insurance and finances, and policies and rights. Participants talked about specific types of discrimination, such as bullying and employment-based discrimination, but also discrimination in general. Some participants described actual experiences with discrimination, as seen in a parent's description of an interaction that her child experienced, “...his girlfriend's mother freaked out and said, ‘You're disgusting’ and forbid her from seeing him” (Mother of a trans boy, age 18 years), which made the participant realize that discrimination will be a part of her child's future life, both in the short-term and long-term. Other participants anticipated discrimination based on their knowledge about discrimination among other TGN individuals.

The theme of insurance and finances arose primarily in relation to gender affirming treatments for the TGN youth, such as pubertal blockers, hormone therapy, and surgical procedures. A youth participant described the complexities of navigating insurance as a TGN individual, in terms of their long-term future, “...all my medical stuff is still listed as female, which I was advised to do because that way if you get cervical cancer or breast cancer or whatever your insurance will cover it” (Trans boy, age 17 years). Regarding finances in the long-term future, one parent said, “...it's a financial concern, just that I'll be able to afford the therapies that [my child] needs” (Mother of a trans boy, age 10 years).

Participants also discussed policies and rights, such as non-discrimination policies in school settings and TGN rights more generally. Many caregivers described how policies and laws shaped how they thought about their child's future. A father of a trans girl, age 8 years, talked about hoping for change to happen at all the schools in the district regarding non-discrimination policies, saying “...once that happens...then I'll feel more comfortable about middle school and high school.” A mother of a trans girl, age 15 years, talked about societal change more broadly in relation to how she imagines her child's long-term future now, compared to when her child came out as transgender 12 years prior,

I think it's more positive because I see that the United States is changing...the laws are passing that are good laws that are going to protect [child] and give her the same rights that everybody else has in the country.

Advocacy

The barriers to envisioning a positive future anticipated by family members appeared to influence other experiences, such as advocacy. The most prominent code in advocacy was activism. Having a TGN youth in the family prompted some participants to engage in activism related to transgender rights. As a mother of a trans girl, age 13 years, described,

We've taken...the opportunity to do some advocacy...to make this world a better place for [child], you know, to raise awareness and to make it more familiar. I think about all the kids in her class that will go, ‘Oh yeah, I had a kid in my class that was trans,’ like no big deal, you know.

For some participants, activism was a form of empowerment and created opportunities for the youth's long-term future, as in the narrative of a trans girl, age 15 years,

I think [being transgender] has definitely given me options for what I can do for a career. I know that I can always fall back on activism and stuff, maybe like something in law regarding this type of situation. So it's given me a firm basis for everything.

Acceptance/support, mental health/emotions, relationships

Barriers to envisioning a positive future anticipated by family members also affected experiences related to acceptance/support, mental health/emotions, and relationships. These three themes were grouped together because acceptance/support from others was directly associated with participants’ mental/health/emotions and relationships and vice versa.

Acceptance/support

Acceptance/support included prominent higher order codes such as: being a good caregiver, supportive communities for the youth, supportive communities for the caregivers and family, and wanting the best for the youth. The concept of being a good caregiver emerged in a number of different higher order codes found primarily among caregiver participants, including wanting to protect their child, wanting to give their child skills and prepare them for the future, and providing support. One parent described being a good parent in relation to her child's short-term future, “...the safest, smartest thing I could do is get this child on the path to being who he feels like he is so that he can start feeling like he belongs” (Mother of a trans boy, age 15 years). A father of a trans girl, age 15 years, described wanting to give his child skills for their long-term future,

...the next thing for me as a parent, as a tactical dad, is to try to get [child] life skills to take care of herself, and I'm having some challenges with that because all the life skills that I have...aren't any good for a trans kid...how do you teach ‘em when you don't know?

Supportive communities for the youth and caregivers primarily referred to the importance of such communities to the participants’ long-term future well-being. As one parent said, “I think friends and community are a big part of living a fulfilled life; I think those are still very possible [for child]” (Mother of a trans boy, age 17 years). Similarly, many caregivers talked about wanting the best for their child in both the short-term and long-term future. One parent described this sentiment in relation to her child undergoing a gender transition, “I want a happy, adjusted child who feels good about himself and who feels good about the world and if [gender transition] is what it takes, then that's what it takes. Let's get going!” (Mother of a trans boy, age 15 years).

Mental health/emotions

Mental health/emotions included prominent higher order codes such as fear, general worry about the future, worries about physical and emotional safety, and happiness. Caregivers expressed fear about a number of different aspects of their child's short-term and long-term future, including gender affirming medical treatments (e.g., surgery) and interacting with other people, as a father of a trans boy, age 15 years, said:

It's one thing to think of your kid as trans. It's another thing thinking of your kid in the hospital going through surgeries and going through gender reassignment, going through all kinds of hormonal treatments and things like that...[it's] very scary. It's very upsetting to me, and it's taking it from an abstraction to a reality.

Caregivers’ worries about physical and emotional safety were largely related to anticipated violence against their child because of their child's transgender identity. One parent said she worries about her child's short-term future in that, “...[child] will go to a playdate at someone's house and they'll be like a psycho-conservative person who goes and kills children like that 'cause they're doing a favor to the world” (Mother of a trans girl, age 7 years). In contrast to the other prominent themes within mental health/emotions, many participants described happiness in the youth's future. In one parent's past conceptualization of the future, she described first learning about her child's transgender identity: “...when we first went down this road, you know, it was harder to picture [child] as happy as she is right now” (Mother of a trans girl, age 14 years).

Relationships

Relationships included prominent higher order codes such as friendships and caregiver-child relationships. Participants often described friendships in terms of acceptance and rejection, especially in relation to being out as transgender. One mother of a trans boy, age 10 years, described that her child was “worried about how his friends were going to react” in the short-term future when he first came out as transgender. Another youth participant anticipated friendships in the short-term future of college, “...you don't make friends because you're trans...I don't really want the fact that I'm trans to decide whether someone's going to be my friend or hang out with me” (Trans boy, age 18 years).

The theme of caregiver-child relationships was also prominent when considering the youth's future. In past conceptualizations of the future, some participants described future thoughts about these relationships when the youth first came out as transgender, “...[child] and I weren't gonna have a stereotypical father-son relationships...I felt a loss for that” (Father of a trans girl, age 8 years). Other caregivers described their relationship with their child going forward into the short-term and long-term future, as in one parent's narrative: “...hopefully [child] will keep our relationship strong, and [both parents] are trying to be as open as we can about anything so that [child] knows that she can...come to us” (Mother of a trans boy, age 10 years).

Approaching the Adjustment and Expectations

Barriers to envisioning a positive future anticipated by family members also affected experiences in two additional areas: approaching the adjustment and expectations. These two themes were grouped together because they both represented cognitive processes related to how the participants thought about the youth's future.

Approaching the adjustment

Approaching the adjustment included prominent higher order codes such as decision-making about being out, is my child really transgender? and uncertainty about the future. Decision-making about being out was typically described in relation to different contexts, such as future school, employment, and extended family gatherings. A mother of a trans boy, age 9 years, described moving to a new town in relation to her son's short-term future:

I asked him: ‘How do you want me to enroll you in this school? Do you want me to enroll you as who you were before or do you want me to enroll you as who you are now?’ And he says: ‘I only want to be known as [child's chosen name]. I only want to be known as a boy. I don't want to be known as the boy who used to be a girl. I don't wanna have to answer questions because people don't understand.

Many caregivers questioned whether their child was really transgender. This was more typical among caregivers of younger children who had recently come out as transgender, than it was among caregivers of adolescents who had been out for some time. A mother of a “girlish boy,” age 8 years, described this uncertainty in thinking about her child's short-term and long-term future:

...he will say technically ‘I'm a boy,’ but...one day there was just me, my younger sister, and him and he put his arms around us and was like ‘I guess it's just us girls now.’ So I think he really identifies and whether that's just a super sensitive new age guy or maybe he's just really meant to be a girl. I don't know.

Uncertainty about the youth's future was expressed by both youth and caregivers, but primarily by the latter. The youngest youth participants often had not thought about their future yet, as one youth participant said “I don't really think about it that much” (Trans boy, age 10 years). But for some caregivers, the uncertainty held more weight and was sometimes described as “scary.” A father of a trans boy, age 15 years, described this process in thinking about the long-term future:

...when I start thinking about the future I get very scared, and I don't know what it holds but I'm sure we'll meet it head on and that's all I can say. Yeah, I really don't know, it gets me nervous.

Expectations

Expectations included prominent higher order codes such as ideal expectations for the youth's future, expectations for romantic relationships, and hopes for the future regarding societal views of LGBTQ issues. Ideal expectations for the youth's future were often described by caregivers as past conceptualizations of the future in the time period before their child came out as TGN. One parent described how her expectations for her child changed when her child came out as transgender: “He was gonna be top 5% of his class, do anything. The world was open to him with all his talents and that just went out the door...I felt like the rug was pulled out from under me” (Mother of a trans boy, age 18 years). A trans girl, age 15 years, described ideal expectations for her long-term future in terms of life goals:

...to carry out my transition, get the [sexual reassignment surgery] and just become fully female... it's gonna be kind of strange after that ‘cause I would have accomplished my quest and I'll be like, ‘I don't know what to do now!’

Expectations for the youth's future romantic relationships were discussed by both youth and caregivers. These expectations related to the timing of romantic relationships (e.g., waiting until the youth is older), being out regarding the youth's TGN identity, and finding partners who are accepting. As one parent described, in relation to their child's long-term future: “...you want [child] to have success with relationships, that sort of thing....the typical human experience, marriage and that sort of thing” (Father of a trans girl, age 13 years). A youth participant talked about how his gender identity might affect romantic relationships in the short-term or long-term future: “If it does, then they weren't the one for me” (Trans boy, age 18 years).

Participants’ hopes for the long-term future regarding LGBTQ issues in society often compared transgender rights to LGB rights, and were generally optimistic. A father of a trans boy, age 15 years, compared transgender issues to LGB issues:

...there's a lot more paths than there used to be...there's a lot of acceptance that wasn't there even a year or two or five years ago, much less ten or twenty years ago...I think [transgender] is the next frontier in acceptance.

As another parent said: “I think that this is going to help the whole world think about gender in a different way that is more about what we feel inside” (Mother of a trans boy, age 10 years).

Identity

Barriers to envisioning a positive future anticipated by family members also affected experiences related to the youth's transgender identity. Identity included prominent higher order codes such as authenticity and personality and behavior. Participants described the concept of authenticity in terms of the child being who they are. One parent described the youth's coming out process, regarding their short-term and long-term future: “...she's figured it out and it makes sense to her and that's who she wants to be moving forward...” (Father of a trans girl, age 13 years). Another parent described hoping that the family can contribute to the youth's authenticity in the short-term or long-term future: “I feel hopeful that we are going to be able to do the things that are going to help [child] feel or to present and look like the boy he feels inside, and the man” (Mother of a trans boy, age 10 years).

Personality and behavior arose in participants’ narratives primarily when caregivers described the youth in ways that were not necessarily gendered or related to the youth's transgender identity (e.g., “popular” or “compassionate”). At times, descriptions of the youth's personality and behavior were related to gender or to the youth's transgender identity, as in one parent's description of their child's long-term future: “I think [being transgender] is going to grow his confidence and compassion for people. I think he's going to be a kind of man that's very nurturing and very wild and energetic” (Mother of a trans boy, age 10 years).

Institutional Factors

The three thematic categories of 1) acceptance, support/mental health, and emotions/relationships; 2) approaching the adjustment, expectations; and 3) identity were all related to thoughts about the youth's future in the short-term, including institutional factors and health/interventions. Institutional factors included prominent higher order codes such as camp, pre-college school, college, work-related issues in the youth's future employment/career, and specific careers for the youth in the youth's future employment/career. Many caregivers of younger youth anticipated experiences related to camp and school prior to college. One parent described her feelings about an upcoming camp experience for her child in the short-term future: “[Child] just found out today that [the school] is not gonna let him room with boys for the 6th grade camp. And so, we are so disappointed” (Mother of a trans boy, age 11 years). A youth participant described anticipating bathroom use at school: “I wouldn't even want to think about what would happen at school if I tried to use the guy's bathroom, which I am not allowed to until I physically transition and have bottom surgery” (Trans boy, age 15 years). Many of the older youth anticipated college and their future employment in the short-term future. One youth participant described an upcoming move for college: “I'm going to a new school in a different country and I don't know anyone, I don't really want to be known as the trans kid anymore” (Trans boy, age 18 years). Another youth participant anticipated challenges with employment in their short-term future when asked by the interviewer how they thought their transgender identity will affect their future: “...finding jobs, ‘cause like, most people don't accept it...Hopefully for the future, for me, I'll be able to have a good job, education, and everything” (Trans girl, age 13 years).

Health/Interventions

Health/interventions included prominent higher order codes such as feelings about gender affirming treatment and professional help. Discussion of gender affirming treatments was common among the participants. Caregivers expressed a number of different emotions and feelings related to their child undergoing gender affirming treatments, including fear, concern, sadness, nervousness, and feeling overwhelmed. One parent described feeling overwhelmed when faced with gender affirming procedures that were potentially in her child's short-term future: “I think going to the daylong conference and learning about the surgery, timing, and the blockers and all that stuff was overwhelming” (Mother of a “girlish boy,” age 8 years). Another parent described feeling sadness related to his child having gender affirming surgery: “...there's a sadness there because you feel like, you know, your body's perfect already, I'm not convinced your body's gonna be better when you alter it surgically” (Father of a trans boy, age 17 years). Many participants had already sought professional help related to the youth's TGN identity and anticipated more professional help in the short-term future, primarily in the form of mental health therapists and doctors. As a mother of a “girlish boy,” age 8 years, said:

I feel like my hope is that he will be okay with who he is and as a family we will feel like we'll find the right care providers to help us make whatever decision we will need to make.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine how TGN youth and their caregivers perceive the youth's future in light of the youths’ gender identity. Two previous studies have examined how transgender adults consider aspects of their future: anticipated stigma (Golub & Gamarel, 2013) and potentially traumatic events (Shipherd et al., 2011). However, these perspectives provide a snapshot of specific types of anticipated future outcomes for transgender adults, rather than examining how transgender youth think about their future in general. This study is the first of its kind to explore the future perspectives of TGN individuals from both youth and caregivers’ perspectives.

The theme of societal factors was particularly important as these factors impacted all of the constructs throughout the conceptual model. Research on social comparison indicates that the future is constructed through anticipated outcomes as compared to similar individuals (e.g., Buunk, 1998; Crosby, 1976). Findings from the current study replicate these concepts; youth and caregivers do not have access to many role models, but the ones they do have will shape hopes, fears, excitement, and worry as the youth continue through their identity process. TGN youth and caregivers in the current study grappled with how to fit in as the youth's gender identity develops, with worries primarily revolving around appearance and gender expectations. West and Zimmerman (1987) contend that individuals are constantly “doing gender,” in that humans intentionally or unintentionally participate in gendered situations and perceptions that reinforce gender norms. Schilt and Westbrook's (2009) research on gender norms and how transgender adults “do gender,” indicates that transgender individuals use cisnormative ways of being gendered to feel normal; however, this research was primarily focused on how transgender adults’ sexualized relationships are gendered. The current study extends previous research by examining gender norms that may exist for TGN youth and how caregivers may reinforce these norms.

Barriers to envisioning a positive future that were described by youth and their caregivers were directly related to how families perceived societal factors. Although research on future perspectives indicates that youth share their fears and concerns related to the future (Seginer, 2009), the individuals in the current study reported barriers that most other youth do not encounter. Research with transgender youth indicates that experiences of discrimination (Grossman & D'Augelli, 2006), difficulty with the healthcare system (Vance et al., 2015), and challenges with policies and legal issues (McGuire et al., 2010) are common. In the current study, anticipated discrimination was based on two factors: a) experiencing discrimination firsthand, thus setting the stage for future experiences; and b) hearing about other TGN individuals’ experiences of discrimination. Previous research with transgender individuals indicates that anticipated negative events and emotions fuel perceptions that all interpersonal interactions are going to be difficult (Budge, Orovecz, & Thai, 2015); however, this anticipation can be both protective and harmful (Link, Wells, Phelan, & Yang, 2015). Participants in this study also described issues in the foreseeable future with insurance companies, such as affording health-care related costs. Although this is a common concern for many families, the burden of covering medical expenses that are not covered by insurance can be financially devastating (Sanchez, Sanchez, & Danoff, 2009). Even if all insurance companies agree to cover transgender-related health care in the future, the stress of anticipating navigating insurance coverage remains.

While many of the future perspectives in this study were rooted in stress and worry as a result of anticipated barriers to envisioning a positive future, TGN youth and caregivers were also hopeful about laws and policies changing for the better. This finding is in line with research that indicates that transgender individuals have positive responses (momentum, hope, and positive emotions) to seeing positive changes in popular culture and laws, which in turn fuels additional change and hope (e.g., Budge et al., 2015; Hines, 2007). This finding is also in line with future perspectives research that highlights hope in contrast to fear (Seginer, 2009). In the current study, caregivers described hope for continued connection among family members and openness regarding unknown future experiences. Retrospective research indicates that transgender adults wished that their family members had reacted in many of the ways the caregivers did within this study (Riley, Clemson, & Sitharthan, 2013).

Upon acknowledging anticipated barriers to envisioning a positive future, three interpersonal themes arose, which were grouped together in the conceptual model: acceptance/support, mental health/emotions, and relationships. A common finding from many psychological studies regarding transgender individuals includes the importance of social support (e.g., Budge et al., 2013; Bockting et al., 2013; Nemoto, Bodeker, & Iwamoto, 2011). The findings from the current study are no exception to this common strategy of coping with anticipated barriers. One finding that deviates from previous research is the concept of caregivers wanting to help their child counter the barriers that the youth may experience in the future, specifically giving the youth skills to deal with future adversity. The caregivers from this sample were overwhelmingly supportive, which suggests that there may be a connection between initial family support and preparation to handle difficulty. Previous research with racial and ethnic minority populations indicates that this type of preparation for youth with minority identities is an essential component of coping and resilience (Hughes & Johnson, 2001; Phinney & Chavira, 1995).

In contrast to the interpersonal reactions to barriers listed above, there were two themes that described cognitive processes that were related to barriers to envisioning a positive future: approaching the adjustment and expectations. All of the TGN youth and caregivers described their thought processes as they were planning for the changes ahead. For example, participants indicated that there were many future decisions to be made and there was uncertainty about identity and what the future might hold. This finding follows initial scholarship on future perspectives describing how uncertain or pessimistic thoughts occur for “socially deprived groups” (Trommsdorff, 1983). The expectations that were described in the current study were primarily focused on the family's value system (e.g., expectations for romantic relationships and independence) or societal expectations (e.g., coming out, sexual orientation). Previous research related to transgender individuals and expectations has focused on transition-related outcomes (e.g., Katz-Wise & Budge, 2015).

The fourth theme related to barriers to envisioning a positive future was identity. Much of previous research conducted with transgender youth has focused on the youth's current transgender identity (e.g., Burgess, 2000; Grossman & D'Augelli, 2006; Pollack & Eyre, 2012); many of the future processes in this study follow the same themes from previous research. As with the current study, previous studies have noted that in the face of barriers, allowing oneself to be authentic regarding gender identity can be incredibly empowering (Singh et al., 2014). As well, research on cisgender youth and future perspectives indicates that confidence about hopes and plans materializing are related to identity processes, thus assisting with exploration and commitment of identity (Seginer & Noyman, 2007). The current findings add to previous research by highlighting that youth and their caregivers wanted the youth to find their authentic self, while also maintaining other non-transgender aspects of their personality and self.

The participants in this study also described shorter-term future aspirations for youth. TGN youth and caregivers described worries and hopes for how the youth will navigate institutions, such as secondary school, college, and camps. In the model, future perspectives related to institutional factors were directly related to interpersonal and cognitive processes associated with youths’ transition and identity experiences. Although institutional factors can be, and are, a part of these experiences, the youths’ future was typically framed logistically (e.g., negotiating bathrooms). However, it was common for youth to express hope for being stealth by being in environments where no one had prior knowledge of their transgender identity.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

There were several limitations to the current study. First, we approached this research question using an exploratory design and framework. As with any exploratory study, there are limitations to how participants are recruited and the generalizability of the information provided. For example, there is a wide range of developmental processes that occur from the ages of 7-18 years, particularly among TGN youth; we acknowledge that future perspectives will look entirely different for youth at age 7 years versus age 18 years. However, the amount of overlap—given the wide age difference—is telling of how close the shared experiences of TGN youth are, even with sample limitations. Future research should determine the different developmental trajectories of future expectations for youth, based on the age at which a youth realized their TGN identity. In addition, future research should quantitatively capture the differences between short-term and long-term expectations to determine the impact on life-functioning and well-being.

TGN youth and caregivers were asked different questions about perceptions of the youth's future, which may have shaped participants’ responses; however, the transcripts as a whole were analyzed for future-related themes, rather than limiting analyses to participants’ responses to future-related questions. Furthermore, TGN youth and caregivers’ interview transcripts were analyzed together, rather than separately. It is possible that analyzing them separately may have yielded different results; however, the themes and conceptual model that emerged from this analysis represent the experiences of both TGN youth and their caregivers. Table 2 reports the number of line by line codes from caregiver vs. youth interviews, which readers may consult for more detailed information regarding which themes appeared in interviews from TGN youth and caregivers.

Another limitation is that the majority of the families were White and upper-middle class. This sample provides a snapshot of the future perspectives of families that fit within this demographic, and is not likely to be representative of families of color and/or from lower socioeconomic (SES) backgrounds. Families of color may have different perceptions of transgender youths’ futures, specifically related to knowledge of higher rates of victimization among transgender individuals of color (Grant et al., 2011); these concerns were not represented within the current dataset. As well, families in the current study displayed a certain amount of economic privilege; for families from lower SES backgrounds, anticipating costly gender affirming medical treatments may impact future perceptions. Future research should focus on the unique future perspectives of families who experience economic and racial marginalization. In addition, caregivers in this study were overwhelmingly supportive of their TGN child; therefore, the results from the current study may not represent families with unsupportive caregiver(s). Future research should focus on interventions that specifically target future perspectives to determine if there are ways to address barriers to envisioning a positive future and interpersonal expectations, and overcome fears regarding uncertainty and negative expectations for the future. Future research should also determine if the current model fits for families who are not as supportive of TGN youth to determine how anticipated events/situations differ based on level of acceptance.

Implications for Practice

There are several implications for counseling psychologists based on the findings from the current study. It will be important to involve all family members in mental health interventions regarding fears and hopes for the youths’ future. This assessment will provide counseling psychologists with a clear understanding of the actual and anticipated barriers to envisioning a positive future faced within the family and lend to specific interpersonally or cognitively-based interventions. For example, some of the cognitive processes that occurred in this study were related to having specific expectations related to a child's future that are no longer relevant once they identify as TGN; the adjustment of these expectations will focus on interventions that address cognitive flexibility and managing affect (such as disappointment and grief) that follow this process. In Budge's work with TGN youth and their families, it is not typically clinically indicated for youth to hear all of the fears their family members have related to their future. Youth appear to internalize the stress of their family members. Instead, it might be useful for all family members to write down their fears and for the therapist to aggregate themes from the writings to assist with a family intervention. It can also be useful for the therapist to ask family members to process their fears with others, so as not to overburden each other (and specifically the youth) with concerns.

If families tend to discuss more uncertainty about how to proceed with decision-making or about how the youth's future identity, cognitive behavioral interventions geared toward transgender individuals (e.g., Austin & Craig, 2015) and mindfulness-based and acceptance and commitment (ACT) exercises (Gerhart, 2012; McHugh, 2011) can help families cope with ambiguity and uncertainty. One intervention that might enhance planning for the future is an exercise in which the therapist outlines themes from the current study on separate sheets of paper and asks each family member to list their expectations and worries based on each theme. Then, family members can discuss coping mechanisms and how they want to work together as a family on each of these issues. This exercise can assist family members in understanding each other's expectations and derive developmentally-appropriate problem solving for each family member.

The research in the current study indicates that caregivers are concerned about what will occur if a child “changes their mind” (a developmentally appropriate evolution of identity exploration); in Budge's clinical practice this is a frequent concern of caregivers of TGN youth. Much of psychoeducation focuses on normalizing identity development and fluidity in youth, and sharing findings from research indicating no long-term negative psychological effects of youth being affirmed with their current gender identity and identifying differently later. It is also useful to discuss the process of how the family wants to communicate if a youth is questioning aspects of their gender process and how the family can support and problem solve these issues. It is our hope that the current study will contribute to a new understanding of family dynamics regarding future perspectives for TGN youth, and will jumpstart a new line of research in which family dynamics and family interventions are created and researched for effectiveness.

Public Significance Statement.

This research suggests that transgender and gender nonconforming (TGN) youth and their caregivers perceptions of the youth's future are related to societal norms about gender and knowledge of discrimination against transgender individuals. Clinical work and interventions for families with TGN youth should consider how TGN youth and caregivers are thinking about the youth's future and how this may impact the family's ability to support the youth in their gender transition.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Katz-Wise was funded by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (K99HD082340). This work was presented at the National Transgender Health Summit in 2015. We would like to thank the following individuals for contributing their time to this research as consultants, interviewers, and coders: Scott Leibowitz, S. Bryn Austin, Kate McLaughlin, Danielle Alexander, Sebastian Barr, Yasmeen Chism, Jacob Eleazer, Kaleigh Flanagan, Clare Gervasi, Ariel Glantz, Dylan Hiner, Cheré Hunter, Amaya Perez-Brumer, Jackson Painter, Brian Rood, Patrick Sherwood, and Jayden Thai. We would also like to thank the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Expression (SOGIE) Working Group at Boston Children's Hospital and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and the Trans* Lab at the University of Louisville for their invaluable feedback. Finally, we would especially like to thank the youth and families who shared their stories with us.

Contributor Information

Sabra L. Katz-Wise, Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children's Hospital, Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

Stephanie L. Budge, Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, WI.

Joe J. Orovecz, Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Wisconsin – Madison.

Bradford Nguyen, School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, CA.

Brett Nava-Coulter, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA.

Katharine Thomson, Department of Psychiatry, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC.: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, Craig SL. Transgender affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy: Clinical considerations and applications. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice. 2015;46:21–29. doi:10.1037/a0038642. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Beck a T., Weissman a, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. doi:10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:943–951. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Adelson JL, Howard KA. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:545–557. doi: 10.1037/a0031774. doi:10.1037/a0031774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Katz-Wise SL, Tebbe EN, Howard KA, Schneider CL, Rodriguez A. Transgender emotional and coping processes: Facilitative and avoidant coping throughout gender transitioning. The Counseling Psychologist. 2013;41:601–647. doi:10.1177/0011000011432753. [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Orovecz JJ, Thai JL. Trans men's positive emotions: The interaction of gender identity and emotion labels. The Counseling Psychologist. 2015;43:404–434. doi: 10.1177/0011000014565715. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess C. Internal and external stress factors associated with the identity development of transgendered youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2000;10:35–47. doi:10.1300/J041v10n03_03. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk B. Social comparison and optimism about one's relational future: Order effects in social judgment. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1998;28:777–786. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; London: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Holden RR. Multidimensional future time perspective as moderators of the relationships between suicide motivation, preparation, and its predictors. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2013;43:395–405. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12025. doi:10.1111/sltb.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolhart D, Baker A, Farmer S, Malaney M, Shipman D. Therapy with transsexual youth and their families: A clinical tool for assessing youth's readiness for gender transition. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2013;39:223–243. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00283.x. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby F. A model of egoistical relative deprivation. Psychological Review. 1976;83:85–113. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.83.2.85. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M. Seeking refuge under the umbrella: Inclusion, exclusion, and organizing within the category transgender. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2007;4:60–80. doi:10.1525/srsp.2007.4.4.60. [Google Scholar]

- Difulvio GT. Experiencing violence and enacting resilience: The case story of a transgender youth. Violence Against Women. 2015;21:1385–1405. doi: 10.1177/1077801214545022. doi:10.1177/1077801214545022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher J. Queer diagnoses: Parallels and contrasts in the history of homosexuality, gender variance, and the diagnostic and statistical manual. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:427–460. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9531-5. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards-Leeper L, Spack NP. Psychological evaluation and medical treatment of transgender youth in an interdisciplinary “Gender Management Service” (GeMS) in a major pediatric center. Journal of Homosexuality. 2012;59:321–336. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.653302. doi:10.1080/00918369.2012.653302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]