Abstract

Qualitative description (QD) is a term that is widely used to describe qualitative studies of health care and nursing-related phenomena. However, limited discussions regarding QD are found in the existing literature. In this systematic review, we identified characteristics of methods and findings reported in research articles published in 2014 whose authors identified the work as QD. After searching and screening, data were extracted from the sample of 55 QD articles and examined to characterize research objectives, design justification, theoretical/philosophical frameworks, sampling and sample size, data collection and sources, data analysis, and presentation of findings. In this review, three primary findings were identified. First, despite inconsistencies, most articles included characteristics consistent with limited, available QD definitions and descriptions. Next, flexibility or variability of methods was common and desirable for obtaining rich data and achieving understanding of a phenomenon. Finally, justification for how a QD approach was chosen and why it would be an appropriate fit for a particular study was limited in the sample and, therefore, in need of increased attention. Based on these findings, recommendations include encouragement to researchers to provide as many details as possible regarding the methods of their QD study so that readers can determine whether the methods used were reasonable and effective in producing useful findings.

Keywords: qualitative description, qualitative research, systematic review

Qualitative description (QD) is a label used in qualitative research for studies which are descriptive in nature, particularly for examining health care and nursing-related phenomena (Polit & Beck, 2009, 2014). QD is a widely cited research tradition and has been identified as important and appropriate for research questions focused on discovering the who, what, and where of events or experiences and gaining insights from informants regarding a poorly understood phenomenon. It is also the label of choice when a straight description of a phenomenon is desired or information is sought to develop and refine questionnaires or interventions (Neergaard et al., 2009; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2005).

Despite many strengths and frequent citations of its use, limited discussions regarding QD are found in qualitative research textbooks and publications. To the best of our knowledge, only seven articles include specific guidance on how to design, implement, analyze, or report the results of a QD study (Milne & Oberle, 2005; Neergaard, Olesen, Andersen, & Sondergaard, 2009; Sandelowski, 2000, 2010; Sullivan-Bolyai, Bova, & Harper, 2005; Vaismoradi, Turunen, & Bondas, 2013; Willis, Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, & Zichi-Cohen, 2016). Furthermore, little is known about characteristics of QD as reported in journal-published, nursing-related, qualitative studies. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to describe specific characteristics of methods and findings of studies reported in journal articles (published in 2014) self-labeled as QD. In this review, we did not have a goal to judge whether QD was done correctly but rather to report on the features of the methods and findings.

Features of QD

Several QD design features and techniques have been described in the literature. First, researchers generally draw from a naturalistic perspective and examine a phenomenon in its natural state (Sandelowski, 2000). Second, QD has been described as less theoretical compared to other qualitative approaches (Neergaard et al., 2009), facilitating flexibility in commitment to a theory or framework when designing and conducting a study (Sandelowski, 2000, 2010). For example, researchers may or may not decide to begin with a theory of the targeted phenomenon and do not need to stay committed to a theory or framework if their investigations take them down another path (Sandelowski, 2010). Third, data collection strategies typically involve individual and/or focus group interviews with minimal to semi-structured interview guides (Neergaard et al., 2009; Sandelowski, 2000). Fourth, researchers commonly employ purposeful sampling techniques such as maximum variation sampling which has been described as being useful for obtaining broad insights and rich information (Neergaard et al., 2009; Sandelowski, 2000). Fifth, content analysis (and in many cases, supplemented by descriptive quantitative data to describe the study sample) is considered a primary strategy for data analysis (Neergaard et al., 2009; Sandelowski, 2000). In some instances thematic analysis may also be used to analyze data; however, experts suggest care should be taken that this type of analysis is not confused with content analysis (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). These data analysis approaches allow researchers to stay close to the data and as such, interpretation is of low-inference (Neergaard et al., 2009), meaning that different researchers will agree more readily on the same findings even if they do not choose to present the findings in the same way (Sandelowski, 2000). Finally, representation of study findings in published reports is expected to be straightforward, including comprehensive descriptive summaries and accurate details of the data collected, and presented in a way that makes sense to the reader (Neergaard et al., 2009; Sandelowski, 2000).

It is also important to acknowledge that variations in methods or techniques may be appropriate across QD studies (Sandelowski, 2010). For example, when consistent with the study goals, decisions may be made to use techniques from other qualitative traditions, such as employing a constant comparative analytic approach typically associated with grounded theory (Sandelowski, 2000).

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Screening

The PubMed electronic database was searched for articles written in English and published from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014, using the terms, “qualitative descriptive study,” “qualitative descriptive design,” and “qualitative description,” combined with “nursing.” This specific publication year, “2014,” was chosen because it was the most recent full year at the time of beginning this systematic review. As we did not intend to identify trends in QD approaches over time, it seemed reasonable to focus on the nursing QD studies published in a certain year. The inclusion criterion for this review was data-based, nursing-related, research articles in which authors used the terms QD, qualitative descriptive study, or qualitative descriptive design in their titles or abstracts as well as in the main texts of the publication.

All articles yielded through an initial search in PubMed were exported into EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, 2014), a reference management software, and duplicates were removed. Next, titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine if the publication met inclusion criteria; all articles meeting inclusion criteria were then read independently in full by two authors (HK and JS) to determine if the terms – QD or qualitative descriptive study/design – were clearly stated in the main texts. Any articles in which researchers did not specifically state these key terms in the main text were then excluded, even if the terms had been used in the study title or abstract. In one article, for example, although “qualitative descriptive study” was reported in the published abstract, the researchers reported a “qualitative exploratory design” in the main text of the article (Sundqvist & Carlsson, 2014); therefore, this article was excluded from our review. Despite the possibility that there may be other QD studies published in 2014 that were not labeled as such, to facilitate our screening process we only included articles where the researchers clearly used our search terms for their approach. Finally, the two authors compared, discussed, and reconciled their lists of articles with a third author (CB).

Study Selection

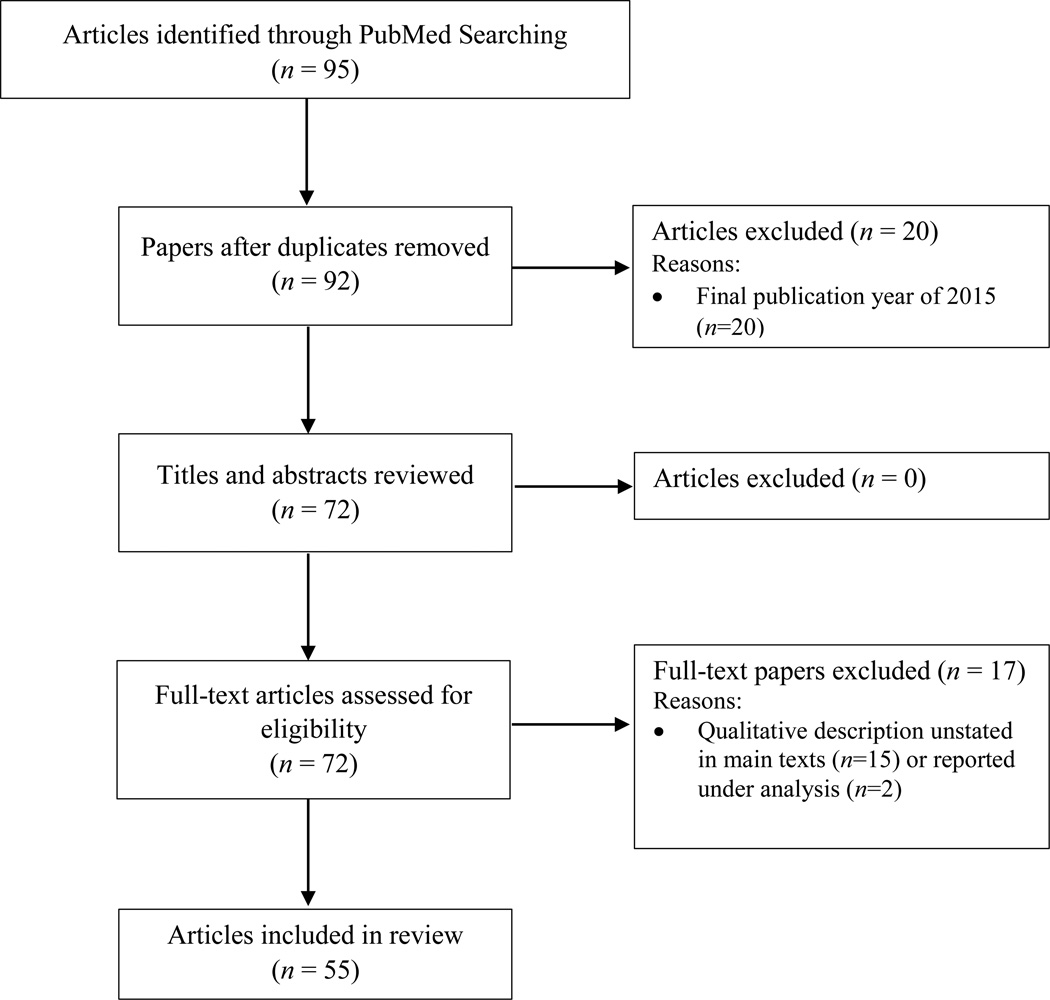

Initially, although the year 2014 was specifically requested, 95 articles were identified (due to ahead of print/Epub) and exported into the EndNote program. Three duplicate publications were removed and the 20 articles with final publication dates of 2015 were also excluded. The remaining 72 articles were then screened by examining titles, abstracts, and full-texts. Based on our inclusion criteria, 15 (of 72) were then excluded because QD or QD design/study was not identified in the main text. We then re-examined the remaining 57 articles and excluded two additional articles that did not meet inclusion criteria (e.g., QD was only reported as an analytic approach in the data analysis section). The remaining 55 publications met inclusion criteria and comprised the sample for our systematic review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Study Selection

Of the 55 publications, 23 originated from North America (17 in the United States; 6 in Canada), 12 from Asia, 11 from Europe, 7 from Australia and New Zealand, and 2 from South America. Eleven studies were part of larger research projects and two of them were reported as part of larger mixed-methods studies. Four were described as a secondary analysis.

Quality Appraisal Process

Following the identification of the 55 publications, two authors (HK and JS) independently examined each article using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist (CASP, 2013). The CASP was chosen to determine the general adequacy (or rigor) of the qualitative studies included in this review as the CASP criteria are generic and intend to be applied to qualitative studies in general. In addition, the CASP was useful because we were able to examine the internal consistency between study aims and methods and between study aims and findings as well as the usefulness of findings (CASP, 2013). The CASP consists of 10 main questions with several sub-questions to consider when making a decision about the main question (CASP, 2013). The first two questions have reviewers examine the clarity of study aims and appropriateness of using qualitative research to achieve the aims. With the next eight questions, reviewers assess study design, sampling, data collection, and analysis as well as the clarity of the study’s results statement and the value of the research. We used the seven questions and 17 sub-questions related to methods and statement of findings to evaluate the articles. The results of this process are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

CASP Questions and Quality Appraisal Results (N = 55)

| CASP Questions • CASP Subquestions |

Results |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can’t tell | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | ||||||

| • Did the researcher justify the research design? | 26 | 47.3 | 28 | 50.9 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | ||||||

| • Did the researcher explain how the participants were selected? | 44 | 80 | 6 | 10.9 | 5 | 9.1 |

| Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | ||||||

| • Was the setting for data collection justified? | 31 | 56.4 | 21 | 38.2 | 3 | 5.4 |

| • Was it clear how data were collected e.g., focus group, semistructured interview etc.? | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| • Did the researcher justify the methods chosen? | 13 | 23.6 | 41 | 74.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Did the researcher make the methods explicit e.g., for the interview method, was there an indication of how interviews were conducted, or did they use a topic guide? | 51 | 92.7 | 4 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| • Was the form of data clear e.g., tape recordings, video materials, notes, etc.? | 54 | 98.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Did the researcher discuss saturation of data? | 20 | 36.4 | 35 | 63.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | ||||||

| • Did the researcher critically examine their own role, potential bias, and influence during data collection, including sample recruitment and choice of location | 4 | 7.3 | 50 | 90.9 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | ||||||

| • Was there sufficient detail about how the research was explained to participants for the reader to assess whether ethical standards were maintained? | 49 | 89.1 | 4 | 7.3 | 2 | 3.6 |

| • Was approval sought from an ethics committee? | 51 | 92.7 | 4 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | ||||||

| • Was there an in-depth description of the analysis process? | 46 | 83.6 | 9 | 16.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| • Was thematic or content analysis used. If so, was it clear how the categories/themes derived from the data? | 51 | 92.7 | 3 | 5.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Did the researcher critically examine their own role, potential bias and influence during analysis and selection of data for presentation? | 20 | 36.4 | 30 | 54.5 | 5 | 9.1 |

| Was there a clear statement of findings? | ||||||

| • Were the findings explicit? | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| • Did the researcher discuss the credibility of their findings (e.g., triangulation) | 46 | 83.6 | 8 | 14.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Were the findings discussed in relation to the original research question? | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note. The CASP questions are adapted from “10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research,” by Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2013, retrieved from http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf. Its license can be found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

Once articles were assessed by the two authors independently, all three authors discussed and reconciled our assessment. No articles were excluded based on CASP results; rather, results were used to depict the general adequacy (or rigor) of all 55 articles meeting inclusion criteria for our systematic review. In addition, the CASP was included to enhance our examination of the relationship between the methods and the usefulness of the findings documented in each of the QD articles included in this review.

Process for Data Extraction and Analysis

To further assess each of the 55 articles, data were extracted on: (a) research objectives, (b) design justification, (c) theoretical or philosophical framework, (d) sampling and sample size, (e) data collection and data sources, (f) data analysis, and (g) presentation of findings (see Table 2). We discussed extracted data and identified common and unique features in the articles included in our systematic review. Findings are described in detail below and in Table 3.

Table 2.

Elements for Data Extraction

| Elements | Data Extraction |

|---|---|

| Research objectives | • Verbs used in objectives or aims |

| • Focuses of study | |

| Design justification | • If the article cited references for qualitative description |

| • If the article offered rationale to choose qualitative description | |

| • References cited | |

| • Rationale reported | |

| Theoretical or

philosophical frameworks |

• If the article has theoretical or philosophical frameworks for study |

| • Theoretical or philosophical frameworks reported | |

| • How the frameworks were used in data collection and analysis | |

| Sampling and sample sizes | • Sampling strategies (e.g., purposeful sampling, maximum variation) |

| • Sample size | |

| Data collection and sources | • Data collection techniques (e.g., individual or focus-group interviews, interview guide, surveys, field notes) |

| Data analysis | • Data analysis techniques (e.g., qualitative content analysis, thematic analysis, constant comparison) |

| • If data saturation was achieved | |

| Presentation of findings | • Statement of findings |

| • Consistency with research objectives |

Table 3.

Data Extraction and Analysis Results

| Authors Country |

Research Objectives |

Design justification |

Theoretical/ philosophical frameworks |

Sampling/ sample size |

Data collection and data sources |

Data analysis | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adams et al. (2014) • USA |

• Explore • Responses to communication strategies |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

Not reported (NR) |

• Purposive sampling/ maximum variation • 32 family members |

• Interviews • Observations • Review of daily flow sheet • Demographics |

• Inductive and deductive qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Five themes about family members’ perceptions of nursing communication approaches |

|

Ahlin, Ericson-Lidman, Norberg, and Strandberg (2014) • Sweden |

• Describe • Experiences of using guidelines in daily practice |

• (-) Reference • (+) Rationale • Part of a research program |

NR | • Unspecified • 8 care providers |

• Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

One theme and seven subthemes about care providers’ experiences of using guidelines in daily practice |

|

Al-Zadjali, Keller, Larkey, and Evans (2014) • USA |

• Examine • Culturally specific views of processes and causes of midlife weight gain |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

Health belief model and Kleiman’s explanatory model |

• Unspecified • 19 adults |

• Semistructured, individual interview |

• Conventional content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Three main categories (from the model) and eight subthemes about causes of weight gain in midlife |

|

Asemani et al. (2014) • Iran |

• Explore • Factors initiating responsibility among medical trainees |

• (-) Reference • (+) Rationale |

NR | • Convenience, snowball, and maximum variation sampling • 15 trainees and other professionals |

• Semistructured, individual interview • Interview guide |

• Conventional content analysis • Constant comparison • (+) Data saturation |

Two themes and individual and non- individual-based factors per theme |

|

Atefi, Abdullah, Wong, and Mazlom (2014) • Iran |

• Explore • Factors related to job satisfaction and dissatisfaction |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Convenience sampling • 85 nurses |

• Semistructured focus group interviews • Interview guide |

• Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Three main themes and associated factors regarding job satisfaction and dissatisfaction |

|

Ballangrud, Hall-Lord, Persenius, and Hedelin (2014) • Norway |

• Describe • Perceptions on simulation-based team training |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Strategic sampling • 18 registered nurses |

• Semistructured individual interviews |

• Inductive content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

One main category, three categories, and six sub- categories regarding nurses’ perceptions on simulation-based team training |

|

Benavides-Vaello et al. (2014) • USA |

• Determine • Barriers and supports for attending college and nursing school |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Unspecified • 45 students |

• Focus-group interviews • Using Photovoice and SHOWeD |

• Constant comparison • (-) Data saturation |

Five themes about facilitators and barriers |

|

Bernhard, Zielinski, Ackerson, and English (2014) • USA |

• Explore • Reasons for choosing home birth and birth experiences |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Purposeful sampling • 20 women |

• Semistructured focus-group interviews • Interview guide • Field notes |

• Qualitative content analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Five common themes and concepts about reasons for choosing home birth based on their birth experiences |

|

Bradford and Maude (2014) • New Zealand |

• Explore • Normal fetal activity related to hunger and satiation |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) • Denzin & Lincoln (2011) |

NR | • Purposive sampling • 19 pregnant women |

• Semistructured individual interviews • Open-ended questions |

• Inductive qualitative content analysis • Descriptive statistical analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Four patterns regarding fetal activities in relation to meal anticipation, maternal hunger, maternal meal consummation, and maternal satiety |

|

Canzan, Heilemann, Saiani, Mortari, and Ambrosi (2014) • Italy |

• Explore, describe, and compare • perceptions of nursing caring |

• (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

NR | • Purposive sampling • 20 nurses and 20 patients |

• Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide • Field notes during interviews |

• Unspecified various analytic strategies including constant comparison • (-) Data saturation |

Nursing caring from both patients’ and nurses’ perspectives – a summary of data in visible caring and invisible caring |

|

Chan and Lopez (2014) • Hong Kong |

• Address • How to reduce coronary heart disease risks |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Secondary analysis • Sandelowski (2000) • Neergaard et al (2009) |

NR | • Convenience and snowball sampling • 105 patients |

• Focus-group interviews • Interview guide |

• Content analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Four categories about patients’ abilities to reduce coronary heart disease |

|

Chen, Tsai, Lee, and Lee (2014) • Taiwan |

• Explore • Reasons for young–old people not killing themselves |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Convenience sampling • 31 older adults |

• Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide • Observation with memos/reflective journal |

• Content analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Six themes regarding reasons for not committing to suicide |

|

Cleveland and Bonugli (2014) • USA |

• Explore • Neonatal intensive care unit experiences |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

NR | • Purposive sampling and convenience sample • 15 mothers |

• Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Qualitative content analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Four themes about participants’ experiences of neonatal intensive care unit |

|

DeBruyn, Ochoa-Marin, and Semenic (2014) • Colombia |

• Investigate • Barriers/facilitators to implementing evidence-based nursing |

• (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

Ottawa model for research use: knowledge translation framework |

• Convenience sampling • 13 nursing professionals |

• Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Inductive qualitative content analysis • Constant comparison • (-) Data saturation |

Four main barriers and potential facilitators to evidence-based nursing |

|

Ewens, Chapman, Tulloch, and Hendricks (2014) • Australia |

• Explore • Perceptions and utilization of diaries |

• (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

NR | • Unspecified • 19 patients and families |

• Responses to open-ended questions on survey |

• Unspecified analysis strategy • (-) Data saturation |

Five themes regarding perceptions on use of diaries and descriptive statistics using frequencies of utilization |

|

Fantasia, Sutherland, Fontenot, and Ierardi (2014) • USA |

• Explore • Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about sexual consent |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Part of a larger mixed-method study |

Theory of planned behavior |

• Purposive sampling • snowball sampling • 26 women |

• Semistructured focus-group interviews • Interview guide |

• Content analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Three main categories and subthemes regarding sexual consent |

|

Friman, Wahlberg, Mattiasson, and Ebbeskog (2014) • Sweden |

• Describe • Experiences of knowledge development in wound management |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale: weak • Krippendorf (2004) |

NR | • Purposive sampling • 16 district nurses |

• Individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Three categories and eleven sub-categories about knowledge development experiences in wound management |

|

Gaughan, Logan, Sethna, and Mott (2014) • USA |

• Describe • Parental-pain journey, beliefs about pain, and attitudes/behaviors related to children’s responses |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) • Milne & Oberle (2005) • Part of a larger mixed methods study |

NR | • Purposive sampling • 9 parents |

• Individual interviews • One open- ended question |

• Qualitative content analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Two main themes, categories, and subcategories about parents’ experiences of observing children’s pain |

|

Hart and Mareno (2014) • USA |

• Describe • Challenges and barriers in providing culturally competent care |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) • Secondary analysis |

NR | • Stratified sampling • 253 nurses |

• Written responses to 2 open-ended questions on survey |

• Thematic analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Three themes regarding challenges/barriers |

|

Hasman, Kjaergaard, and Esbensen (2014) • Denmark |

• Describe • Experiences of childbirth |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • A substudy |

NR | • Purposive sampling with maximum variation • Partners of 10 women |

• Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Three themes and four subthemes about partners’ experiences of women’s childbirth |

|

Higgins, van der Riet, Sneesby, and Good (2014) • Australia |

• Explore • Perceptions about medical nutrition and hydration at the end of life |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Borbasi et al (2008) |

NR | • Purposeful sampling • 10 nurses |

• Focus-group interviews |

• “analyzed thematically” • (-) Data saturation |

One main theme and four subthemes regarding nurses’ perceptions on EOL- related medical nutrition and hydration |

|

Holland, Christensen, Shone, Kearney, and Kitzman (2014) • USA |

• Describe • Reasons for leaving a home visiting program early |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Convenience sample • 32 mothers, nurses, and nurse supervisors |

• Semistructured, individual interviews • Focus-group interviews • Interview guide |

• Inductive content analysis • Constant comparison approach • (+) Data saturation |

Three sets of reasons for leaving a home visiting program |

|

Johansson, Hildingsson, and Fenwick (2014) • Sweden |

• Explore and describe • Beliefs and attitudes around the decision for a caesarean section |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Pollit & Beck (2012) • Burns & Grove (2005) |

NR | • Unspecified • 21 males |

• Individual telephone interviews |

• Thematic analysis • Constant comparison approach • (-) Data saturation |

Two themes and subthemes in relation to the research objective |

|

Kao and Tsai (2014) • Taiwan |

• Explore • Illness experiences of early onset of knee osteoarthritis |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Pope & Mays (1995) • Polit & Beck (2004) • Part of a large research series |

NR | • Purposive sampling • 17 adults |

• Semistructured, Individual interviews • Interview guide • Memo/field notes (observations) |

• Inductive content analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Three major themes and nine subthemes regarding experiences of early onset-knee osteoarthritis |

|

Kerr, McKay, Klim, Kelly, and McCann (2014) • Australia |

• Explore • Perceptions about bedside handover (new model) by nurses |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowsk (2000) • Neergaard et al. (2009) |

NR | • Purposive sampling • 30 patients |

• Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Thematic content analysis • (-) Data analysis |

Two dominant themes and related subthemes regarding patients’ thoughts about nurses’ bedside handover |

|

Kneck, Fagerberg, Eriksson, and Lundman (2014) • Sweden |

• Identify • Patterns in learning when living with diabetes |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Purposive sampling with variations in age and sex • 13 participants |

• Semistructured, individual interviews (3 times over 3 years) |

• Saldana’s (2003) analysis process • Inductive qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Five main patterns of learning when living with diabetes for three years following diagnosis |

|

Larocque et al. (2014) • Canada |

• Evaluate • Book chat intervention based on a novel Still Alice |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Part of a larger research project |

NR | • Unspecified • 11 long-term- care staff |

• Questionnaire with two open- ended questions |

• Thematic content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Five themes (positive comments) about the book chat with brief description |

|

Li, Lee, Chen, Jeng, and Chen (2014) • Taiwan |

• Explore • Facilitators and barriers to implementing smoking- cessation counseling services |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Unspecified • 16 nurse- counselors |

• Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Inductive content analysis • Constant comparison • (-) Data saturation |

Two themes and eight subthemes about facilitators and barriers described using 2-4 quotations per subtheme |

|

Lux, Hutcheson, and Peden (2014) • USA |

• Identify • Educational strategies to manage disruptive behavior |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Part of a larger study |

NR | • Unspecified • 9 nurses |

• Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Content analysis procedures • (-) Data saturation |

Two main themes regarding education strategies for nurse educators |

|

Lyndon et al. (2014) • USA |

• Explore • Experiences of difficulty resolving patient- related concerns |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Secondary analysis |

NR | • Unspecified • 1932 physician, nursing, and midwifery professionals |

• E-mail survey with multiple- choice and free- text responses |

• Inductive thematic analysis • Descriptive statistics • (-) Data saturation |

One overarching theme and four subthemes about professionals’ experiences of difficulty resolving patient-related concerns |

|

L. Ma (2014) • Singapore |

• Explicate • Experience of quality of life for older adults |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Parse (2001) |

Parse’s human becoming paradigm |

• Unspecified • 10 elderly residents |

• Individual interviews • Interview questions presented (Parse) |

• Unspecified analysis techniques • (-) Data saturation |

Three themes presented using both participants’ language and the researcher’s language |

|

F. Ma, Li, Liang, Bai, and Song (2014) • China |

• Explore • Perspectives on learning about caring |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Purposeful sampling • 20 nursing students |

• Focus-group interviews • Interview guide |

• Conventional content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Four categories and associated subcategories about facilitators and challenges to learning about caring |

|

Marcinowicz, Abramowicz, Zarzycka, Abramowicz, and Konstantynowicz (2014) • Poland |

• Describe and assess • Components of the patient–nurse relationship and pediatric-ward amenities |

• (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

NR | • Purposeful, maximum variation sampling • 26 parents or caregivers and 22 children |

• Individual interviews |

• Qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Five main topics described from the perspectives of children and parents |

|

Martorella, Boitor, Michaud, and Gelinas (2014) • Canada |

• Evaluate • Acceptability and feasibility of hand-massage therapy |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Secondary to a RCT |

Focused on feasibility and acceptability |

• Unspecified • 40 patients |

• Semistructured, individual interviews • Field notes • Video recording |

• Thematic analysis for acceptability • Quantitative ratings of video items for feasibility • (-) Data analysis |

Summary of data focusing on predetermined indicators of acceptability and descriptive statistics to present feasibility |

|

McDonough, Callans, and Carroll (2014) • USA |

• Understand • Challenges occurring during transitions of care |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) • Part of a larger study |

NR | • Convenience sample • 22 nurses |

• Focus groups • Interview guide |

• Qualitative content analysis methods • (+) Data analysis |

Three themes about challenges regarding transitions of care: |

|

McGilton, Boscart, Brown, and Bowers (2014) • Canada |

• Understand • Factors that influence nurses’ retention in their current job |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Purposeful sampling • 41 nurses |

• Focus-group interviews • Interview guide |

• Directed content analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Nurses’ reasons to stay and leave their current job |

|

Michael, O'Callaghan, Baird, Hiscock, and Clayton (2014) • Australia |

• Extend • Understanding of caregivers’ views on advance care planning |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) • Grounded theory overtone |

NR | • Theoretical sampling • 18 caregivers |

• Semistructured focus group and individual interviews • Interview guide • Vignette technique |

• Inductive, cyclic, and constant comparative analysis • (-) Data analysis |

Three themes regarding caregivers’ perceptions on advance care planning |

|

Miller (2014) • USA |

• Describe • Outcomes older adults with epilepsy hope to achieve in management |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Unspecified • 20 patients |

• Individual interview |

• Conventional content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Six main themes and associated subthemes regarding what older adults hoped to achieve in management of their epilepsy |

|

Oosterveld-Vlug et al. (2014) • The Netherlands |

• Gain • Experience of personal dignity and factors influencing it |

• (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

Model of dignity in illness |

• Maximum variation sampling • 30 nursing home residents |

• Individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Thematic analysis • Constant comparison • (+) Data saturation |

The threatening effect of illness and three domains being threatened by illness in relation to participants’ experiences of personal dignity |

|

Oruche, Draucker, Alkhattab, Knopf, and Mazurcyk (2014) • USA |

• Identify and describe • Needs in mental health services and “ideal” program |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) • There is a primary study |

NR | • Unspecified • 52 family members |

• Semistructured, individual and focus-group interviews |

• “Standard content analytic procedures” with case-ordered meta-matrix • (-) Data saturation |

Two main topics – (a) intervention modalities that would fit family members’ needs in mental health services and (b) topics that programs should address |

|

O'Shea (2014) • USA |

• “What are the perceptions of staff nurses regarding palliative care…?” |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Purposive, convenience sampling • 18 nurses |

• Semistructured and focus-group interviews • Interview guide |

• Ritchie and Spencer’s framework for data analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Five thematic categories and associated subcategories about nurses’ perceptions of palliative care |

|

Peacock, Hammond-Collins, and Forbes (2014) • Canada |

• Describe • Experience of caring for a relative with dementia |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000; 2010) • Secondary analysis • Phenomenological overtone |

NR | • Purposive sampling • 11 bereaved family members |

• Individual interviews • 27 transcripts from the primary study |

• Unspecified • (-) Data saturation |

Five major themes regarding the journey with dementia from the time prior to diagnosis and into bereavement |

|

Peterson et al. (2014) • Canada |

• Describe Experience of fetal fibronectin testing |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2010) • Vaismoradi, Turunen, & Bondas (2013) |

NR | • Unspecified • 17 women |

• Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Conventional content analysis • (+) Data saturation |

One overarching theme, three themes, and six subthemes about women’s experiences of fetal fibronectin testing |

|

Raphael, Waterworth, and Gott (2014) • New Zealand |

• Explore • Role of nurses in providing palliative and end-of-life care |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Pope & Mays (2006) • Part of a larger study |

NR | • Purposeful sampling • 21 nurses |

• Semistructured individual interviews |

• Thematic analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Three themes about practice nurses’ experiences in providing palliative and end-of-life care |

|

Santos, Sandelowski, and Gualda (2014) • Brazil |

• Understand • Experience with postnatal depression |

• (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

NR | • Purposeful, criterion sampling • 15 women with postnatal depression |

• Minimally structured, individual interviews |

• Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Two themes – women’s “bad thoughts” and their four types of responses to fear of harm (with frequencies) |

|

Sharp et al. (2014) • Australia |

• Understand • Experience of peripherally inserted central catheter insertion |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

NR | • Purposeful sampling • 10 patients |

• Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation |

Four themes regarding patients’ experiences of peripherally inserted central catheter insertion |

|

Soule (2014) • USA |

• Discover • Context, values, and background meaning of cultural competency |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

Focused on cultural competence |

• Purposive, maximum variation, and network • 20 experts |

• Semistructured, individual interviews |

• Within-case and across-case analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Three themes regarding cultural competency |

|

Stegenga and Macpherson (2014) • USA |

• Explore and describe • Cancer experience |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Neegaard et al (2009) |

NR | • Unspecified • 15 patients |

• Longitudinal individual interviews (4 time points) • 40 interviews |

• Inductive content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Processes and themes about adolescent identify work and cancer identify work across the illness trajectory |

|

Sturesson and Ziegert (2014) • Sweden |

• Explore • Experiences of giving support to patients during the transition |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

Focused on support and transition |

• Unspecified (but likely purposeful sampling) • 8 nurses |

• Semistructured Individual interviews • Interview guide |

• Content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

One theme, three main categories, and eight associated categories |

|

Tseng, Chen, and Wang (2014) • Taiwan |

• Describe • Process of women’s recovery from stillbirth |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000) |

NR | • Purposeful sampling • 21 women |

• Individual interview techniques |

• Inductive analytic approaches (Thorne, 2004) • (+) Data saturation |

Three stages (themes) regarding the recovery process of Taiwanese women with stillbirth |

|

Vaismoradi, Jordan, Turunen, and Bondas (2014) • Iran |

• Describe • Perspectives of causes of medication errors |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2010) |

NR | • Purposeful sampling • 24 nursing students |

• Focus-group interviews • Observations with notes |

• Content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Two main themes about nursing students’ perceptions on causes of medication errors |

|

Valizadeh et al. (2014) • Iran |

• Explore • Image of nursing |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Purposeful sampling • 18 male nurses |

• Semistructured individual, interviews • Field notes |

• Content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Two main views (themes) on nursing presented with subthemes per view |

|

Villar, Celdran, Faba, and Serrat (2014) • Spain |

• Ascertain • Barriers to sexual expression |

• (-) Reference • (-) Rationale |

NR | • Maximum variation • 100 staff and residents |

• Semistructured, individual interview |

• Content analysis • (-) Data saturation |

40% of participants without identification of barriers and 60% with seven most cited barriers to sexual expression in the long-term care setting |

|

Wiens, Babenko-Mould, and Iwasiw (2014) • Canada |

• Explore • Perceptions of empowerment in academic nursing environments |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000, 2010) |

Theories of structural power in organizations and psychological empowerment |

• Unspecified • 8 clinical instructors |

• Semistructured, individual • interview guide |

• Unspecified (but used pre-determined concepts) • (+) Data saturation |

Structural empowerment and psychological empowerment described using predetermined concepts |

|

Zhang, Shan, and Jiang (2014) • China |

• Investigate • Meaning of life and health experience with chronic illness |

• (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski (2000, 2010) |

Positive health philosophy |

• Purposive, convenience sampling • 11 patients |

• Individual interviews • Observations of daily behavior with field notes |

• Thematic analysis • (-) Data saturation |

Four themes regarding the meaning of life and health when living with chronic illnesses |

Note. NR = not reported

Findings

Quality Appraisal Results

Justification for use of a QD design was evident in close to half (47.3%) of the 55 publications. While most researchers clearly described recruitment strategies (80%) and data collection methods (100%), justification for how the study setting was selected was only identified in 38.2% of the articles and almost 75% of the articles did not include any reason for the choice of data collection methods (e.g., focus-group interviews). In the vast majority (90.9%) of the articles, researchers did not explain their involvement and positionality during the process of recruitment and data collection or during data analysis (63.6%). Ethical standards were reported in greater than 89% of all articles and most articles included an in-depth description of data analysis (83.6%) and development of categories or themes (92.7%). Finally, all researchers clearly stated their findings in relation to research questions/objectives. Researchers of 83.3% of the articles discussed the credibility of their findings (see Table 1).

Research Objectives

In statements of study objectives and/or questions, the most frequently used verbs were “explore” (n = 22) and “describe” (n = 17). Researchers also used “identify” (n = 3), “understand” (n = 4), or “investigate” (n = 2). Most articles focused on participants’ experiences related to certain phenomena (n = 18), facilitators/challenges/factors/reasons (n = 14), perceptions about specific care/nursing practice/interventions (n = 11), and knowledge/attitudes/beliefs (n = 3).

Design Justification

A total of 30 articles included references for QD. The most frequently cited references (n = 23) were “Whatever happened to qualitative description?” (Sandelowski, 2000) and “What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited” (Sandelowski, 2010). Other references cited included “Qualitative description – the poor cousin of health research?” (Neergaard et al., 2009), “Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research” (Pope & Mays, 1995), and general research textbooks (Polit & Beck, 2004, 2012).

In 26 articles (and not necessarily the same as those citing specific references to QD), researchers provided a rationale for selecting QD. Most researchers chose QD because this approach aims to produce a straight description and comprehensive summary of the phenomenon of interest using participants’ language and staying close to the data (or using low inference).

Authors of two articles distinctly stated a QD design, yet also acknowledged grounded-theory or phenomenological overtones by adopting some techniques from these qualitative traditions (Michael, O'Callaghan, Baird, Hiscock, & Clayton, 2014; Peacock, Hammond-Collins, & Forbes, 2014). For example, Michael et al. (2014, p. 1066) reported:

The research used a qualitative descriptive design with grounded theory overtones (Sandelowski, 2000). We sought to provide a comprehensive summary of participants’ views through theoretical sampling; multiple data sources (focus groups [FGs] and interviews); inductive, cyclic, and constant comparative analysis; and condensation of data into thematic representations (Corbin & Strauss, 1990, 2008).

Authors of four additional articles included language suggestive of a grounded-theory or phenomenological tradition, e.g., by employing a constant comparison technique or translating themes stated in participants’ language into the primary language of the researchers during data analysis (Asemani et al., 2014; Li, Lee, Chen, Jeng, & Chen, 2014; Ma, 2014; Soule, 2014). Additionally, Li et al. (2014) specifically reported use of a grounded-theory approach.

Theoretical or Philosophical Framework

In most (n = 48) articles, researchers did not specify any theoretical or philosophical framework. Of those articles in which a framework or philosophical stance was included, the authors of five articles described the framework as guiding the development of an interview guide (Al-Zadjali, Keller, Larkey, & Evans, 2014; DeBruyn, Ochoa-Marin, & Semenic, 2014; Fantasia, Sutherland, Fontenot, & Ierardi, 2014; Ma, 2014; Wiens, Babenko-Mould, & Iwasiw, 2014). In two articles, data analysis was described as including key concepts of a framework being used as pre-determined codes or categories (Al-Zadjali et al., 2014; Wiens et al., 2014). Oosterveld-Vlug et al. (2014) and Zhang, Shan, and Jiang (2014) discussed a conceptual model and underlying philosophy in detail in the background or discussion section, although the model and philosophy were not described as being used in developing interview questions or analyzing data.

Sampling and Sample Size

In 38 of the 55 articles, researchers reported ‘purposeful sampling’ or some derivation of purposeful sampling such as convenience (n = 10), maximum variation (n = 8), snowball (n = 3), and theoretical sampling (n = 1). In three instances (Asemani et al., 2014; Chan & Lopez, 2014; Soule, 2014), multiple sampling strategies were described, for example, a combination of snowball, convenience, and maximum variation sampling. In articles where maximum variation sampling was employed, “variation” referred to seeking diversity in participants’ demographics (n = 7; e.g., age, gender, and education level), while one article did not include details regarding how their maximum variation sampling strategy was operationalized (Marcinowicz, Abramowicz, Zarzycka, Abramowicz, & Konstantynowicz, 2014). Authors of 17 articles did not specify their sampling techniques.

Sample sizes ranged from 8 to 1,932 with nine studies in the 8–10 participant range and 24 studies in the 11–20 participant range. The participant range of 21–30 and 31–50 was reported in eight articles each. Six studies included more than 50 participants. Two of these articles depicted quite large sample sizes (N=253, Hart & Mareno, 2014; N=1,932, Lyndon et al., 2014) and the authors of these articles described the use of survey instruments and analysis of responses to open-ended questions. This was in contrast to studies with smaller sample sizes where individual interviews and focus groups were more commonly employed.

Data Collection and Data Sources

In a majority of studies, researchers collected data through individual (n = 39) and/or focus-group (n = 14) interviews that were semistructured. Most researchers reported that interviews were audiotaped (n = 51) and interview guides were described as the primary data collection tool in 29 of the 51 studies. In some cases, researchers also described additional data sources, for example, taking memos or field notes during participant observation sessions or as a way to reflect their thoughts about interviews (n = 10). Written responses to open-ended questions in survey questionnaires were another type of data source in a small number of studies (n = 4).

Data Analysis

The analysis strategy most commonly used in the QD studies included in this review was qualitative content analysis (n = 30). Among the studies where this technique was used, most researchers described an inductive approach; researchers of two studies analyzed data both inductively and deductively. Thematic analysis was adopted in 14 studies and the constant comparison technique in 10 studies. In nine studies, researchers employed multiple techniques to analyze data including qualitative content analysis with constant comparison (Asemani et al., 2014; DeBruyn et al., 2014; Holland, Christensen, Shone, Kearney, & Kitzman, 2014; Li et al., 2014) and thematic analysis with constant comparison (Johansson, Hildingsson, & Fenwick, 2014; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., 2014). In addition, five teams conducted descriptive statistical analysis using both quantitative and qualitative data and counting the frequencies of codes/themes (Ewens, Chapman, Tulloch, & Hendricks, 2014; Miller, 2014; Santos, Sandelowski, & Gualda, 2014; Villar, Celdran, Faba, & Serrat, 2014) or targeted events through video monitoring (Martorella, Boitor, Michaud, & Gelinas, 2014). Tseng, Chen, and Wang (2014) cited Thorne, Reimer Kirkham, and O’Flynn-Magee (2004)’s interpretive description as the inductive analytic approach. In five out of 55 articles, researchers did not specifically name their analysis strategies, despite including descriptions about procedural aspects of data analysis. Researchers of 20 studies reported that data saturation for their themes was achieved.

Presentation of Findings

Researchers described participants’ experiences of health care, interventions, or illnesses in 18 articles and presented straightforward, focused, detailed descriptions of facilitators, challenges, factors, reasons, and causes in 15 articles. Participants’ perceptions of specific care, interventions, or programs were described in detail in 11 articles. All researchers presented their findings with extensive descriptions including themes or categories. In 25 of 55 articles, figures or tables were also presented to illustrate or summarize the findings. In addition, the authors of three articles summarized, organized, and described their data using key concepts of conceptual models (Al-Zadjali et al., 2014; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., 2014; Wiens et al., 2014). Martorella et al. (2014) assessed acceptability and feasibility of hand massage therapy and arranged their findings in relation to pre-determined indicators of acceptability and feasibility. In one longitudinal QD study (Kneck, Fagerberg, Eriksson, & Lundman, 2014), the researchers presented the findings as several key patterns of learning for persons living with diabetes; in another longitudinal QD study (Stegenga & Macpherson, 2014), findings were presented as processes and themes regarding patients’ identity work across the cancer trajectory. In another two studies, the researchers described and compared themes or categories from two different perspectives, such as patients and nurses (Canzan, Heilemann, Saiani, Mortari, & Ambrosi, 2014) or parents and children (Marcinowicz et al., 2014). Additionally, Ma (2014) reported themes using both participants’ language and the researcher’s language.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we examined and reported specific characteristics of methods and findings reported in journal articles self-identified as QD and published during one calendar year. To accomplish this we identified 55 articles that met inclusion criteria, performed a quality appraisal following CASP guidelines, and extracted and analyzed data focusing on QD features. In general, three primary findings emerged. First, despite inconsistencies, most QD publications had the characteristics that were originally observed by Sandelowski (2000) and summarized by other limited available QD literature. Next, there are no clear boundaries in methods used in the QD studies included in this review; in a number of studies, researchers adopted and combined techniques originating from other qualitative traditions to obtain rich data and increase their understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. Finally, justification for how QD was chosen and why it would be an appropriate fit for a particular study is an area in need of increased attention.

In general, the overall characteristics were consistent with design features of QD studies described in the literature (Neergaard et al., 2009; Sandelowski, 2000, 2010; Vaismoradi et al., 2013). For example, many authors reported that study objectives were to describe or explore participants’ experiences and factors related to certain phenomena, events, or interventions. In most cases, these authors cited Sandelowski (2000) as a reference for this particular characteristic. It was rare that theoretical or philosophical frameworks were identified, which also is consistent with descriptions of QD. In most studies, researchers used purposeful sampling and its derivative sampling techniques, collected data through interviews, and analyzed data using qualitative content analysis or thematic analysis. Moreover, all researchers presented focused or comprehensive, descriptive summaries of data including themes or categories answering their research questions. These characteristics do not indicate that there are correct ways to do QD studies; rather, they demonstrate how others designed and produced QD studies.

In several studies, researchers combined techniques that originated from other qualitative traditions for sampling, data collection, and analysis. This flexibility or variability, a key feature of recently published QD studies, may indicate that there are no clear boundaries in designing QD studies. Sandelowski (2010) articulated: “in the actual world of research practice, methods bleed into each other; they are so much messier than textbook depictions” (p. 81). Hammersley (2007) also observed:

“We are not so much faced with a set of clearly differentiated qualitative approaches as with a complex landscape of variable practice in which the inhabitants use a range of labels (‘ethnography’, ‘discourse analysis’, ‘life history work’, narrative study’, ……, and so on) in diverse and open-ended ways in order to characterize their orientation, and probably do this somewhat differently across audiences and occasions” (p. 293).

This concept of having no clear boundaries in methods when designing a QD study should enable researchers to obtain rich data and produce a comprehensive summary of data through various data collection and analysis approaches to answer their research questions. For example, using an ethnographical approach (e.g., participant observation) in data collection for a QD study may facilitate an in-depth description of participants’ nonverbal expressions and interactions with others and their environment as well as situations or events in which researchers are interested (Kawulich, 2005). One example found in our review is that Adams et al. (2014) explored family members’ responses to nursing communication strategies for patients in intensive care units (ICUs). In this study, researchers conducted interviews with family members, observed interactions between healthcare providers, patients, and family members in ICUs, attended ICU rounds and family meetings, and took field notes about their observations and reflections. Accordingly, the variability in methods provided Adams and colleagues (2014) with many different aspects of data that were then used to complement participants’ interviews (i.e., data triangulation). Moreover, by using a constant comparison technique in addition to qualitative content analysis or thematic analysis in QD studies, researchers compare each case with others looking for similarities and differences as well as reasoning why differences exist, to generate more general understanding of phenomena of interest (Thorne, 2000). In fact, this constant comparison analysis is compatible with qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis and we found several examples of using this approach in studies we reviewed (Asemani et al., 2014; DeBruyn et al., 2014; Holland et al., 2014; Johansson et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., 2014).

However, this flexibility or variability in methods of QD studies may cause readers’ as well as researchers’ confusion in designing and often labeling qualitative studies (Neergaard et al., 2009). Especially, it could be difficult for scholars unfamiliar with qualitative studies to differentiate QD studies with “hues, tones, and textures” of qualitative traditions (Sandelowski, 2000, p. 337) from grounded theory, phenomenological, and ethnographical research. In fact, the major difference is in the presentation of the findings (or outcomes of qualitative research) (Neergaard et al., 2009; Sandelowski, 2000). The final products of grounded theory, phenomenological, and ethnographical research are a generation of a theory, a description of the meaning or essence of people’s lived experience, and an in-depth, narrative description about certain culture, respectively, through researchers’ intensive/deep interpretations, reflections, and/or transformation of data (Streubert & Carpenter, 2011). In contrast, QD studies result in “a rich, straight description” of experiences, perceptions, or events using language from the collected data (Neergaard et al., 2009) through low-inference (or data-near) interpretations during data analysis (Sandelowski, 2000, 2010). This feature is consistent with our finding regarding presentation of findings: in all QD articles included in this systematic review, the researchers presented focused or comprehensive, descriptive summaries to their research questions.

Finally, an explanation or justification of why a QD approach was chosen or appropriate for the study aims was not found in more than half of studies in the sample. While other qualitative approaches, including grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, and narrative analysis, are used to better understand people’s thoughts, behaviors, and situations regarding certain phenomena (Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2005), as noted above, the results will likely read differently than those for a QD study (Carter & Little, 2007). Therefore, it is important that researchers accurately label and justify their choices of approach, particularly for studies focused on participants’ experiences, which could be addressed with other qualitative traditions. Justifying one’s research epistemology, methodology, and methods allows readers to evaluate these choices for internal consistency, provides context to assist in understanding the findings, and contributes to the transparency of choices, all of which enhance the rigor of the study (Carter & Little, 2007; Wu, Thompson, Aroian, McQuaid, & Deatrick, 2016).

Use of the CASP tool drew our attention to the credibility and usefulness of the findings of the QD studies included in this review. Although justification for study design and methods was lacking in many articles, most authors reported techniques of recruitment, data collection, and analysis that appeared. Internal consistencies among study objectives, methods, and findings were achieved in most studies, increasing readers’ confidence that the findings of these studies are credible and useful in understanding under-explored phenomenon of interest.

In summary, our findings support the notion that many scholars employ QD and include a variety of commonly observed characteristics in their study design and subsequent publications. Based on our review, we found that QD as a scholarly approach allows flexibility as research questions and study findings emerge. We encourage authors to provide as many details as possible regarding how QD was chosen for a particular study as well as details regarding methods to facilitate readers’ understanding and evaluation of the study design and rigor. We acknowledge the challenge of strict word limitation with submissions to print journals; potential solutions include collaboration with journal editors and staff to consider creative use of charts or tables, or using more citations and less text in background sections so that methods sections are robust.

Limitations

Several limitations of this review deserve mention. First, only articles where researchers explicitly stated in the main body of the article that a QD design was employed were included. In contrast, articles labeled as QD in only the title or abstract, or without their research design named were not examined due to the lack of certainty that the researchers actually carried out a QD study. As a result, we may have excluded some studies where a QD design was followed. Second, only one database was searched and therefore we did not identify or describe potential studies following a QD approach that were published in non-PubMed databases. Third, our review is limited by reliance on what was included in the published version of a study. In some cases, this may have been a result of word limits or specific styles imposed by journals, or inconsistent reporting preferences of authors and may have limited our ability to appraise the general adequacy with the CASP tool and examine specific characteristics of these studies.

Conclusions

A systematic review was conducted by examining QD research articles focused on nursing-related phenomena and published in one calendar year. Current patterns include some characteristics of QD studies consistent with the previous observations described in the literature, a focus on the flexibility or variability of methods in QD studies, and a need for increased explanations of why QD was an appropriate label for a particular study. Based on these findings, recommendations include encouragement to authors to provide as many details as possible regarding the methods of their QD study. In this way, readers can thoroughly consider and examine if the methods used were effective and reasonable in producing credible and useful findings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the John A. Hartford Foundation’s National Hartford Centers of Gerontological Nursing Excellence Award Program.

Hyejin Kim is a Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA Predoctoral Fellow (F31NR015702) and 2013–2015 National Hartford Centers of Gerontological Nursing Excellence Patricia G. Archbold Scholar. Justine Sefcik is a Ruth L. Kirschstein Predoctoral Fellow (F31NR015693) through the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Hyejin Kim, MSN, CRNP, Doctoral Candidate, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Justine S. Sefcik, MS, RN, Doctoral Candidate, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Christine Bradway, PhD, CRNP, FAAN, Associate Professor of Gerontological Nursing, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

References

- Adams JA, Anderson RA, Docherty SL, Tulsky JA, Steinhauser KE, Bailey DE., Jr Nursing strategies to support family members of ICU patients at high risk of dying. Heart & Lung. 2014;43(5):406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlin J, Ericson-Lidman E, Norberg A, Strandberg G. Care providers' experiences of guidelines in daily work at a municipal residential care facility for older people. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2014;28(2):355–363. doi: 10.1111/scs.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zadjali M, Keller C, Larkey L, Evans B. GCC women: causes and processes of midlife weight gain. Health Care for Women International. 2014;35(11–12):1267–1286. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.900557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asemani O, Iman MT, Moattari M, Tabei SZ, Sharif F, Khayyer M. An exploratory study on the elements that might affect medical students' and residents' responsibility during clinical training. Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine. 2014;7:8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atefi N, Abdullah KL, Wong LP, Mazlom R. Factors influencing registered nurses perception of their overall job satisfaction: a qualitative study. International Nursing Review. 2014;61(3):352–360. doi: 10.1111/inr.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballangrud R, Hall-Lord ML, Persenius M, Hedelin B. Intensive care nurses' perceptions of simulation-based team training for building patient safety in intensive care: a descriptive qualitative study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2014;30(4):179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides-Vaello S, Katz JR, Peterson JC, Allen CB, Paul R, Charette-Bluff AL, Morris P. Nursing and health sciences workforce diversity research using. PhotoVoice: a college and high school student participatory project. Journal of Nursing Education. 2014;53(4):217–222. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20130326-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard C, Zielinski R, Ackerson K, English J. Home birth after hospital birth: women's choices and reflections. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2014;59(2):160–166. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbasi S, Jackson D, Langford RW. Navigating the maze of nursing research: An interactive learning adventure. 2nd. New South Wales, Australia: Mosby/Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford B, Maude R. Fetal response to maternal hunger and satiation - novel finding from a qualitative descriptive study of maternal perception of fetal movements. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14:288. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns N, Grove SK. The practice of nursing research: Conduct, critique, & utilization. 5th. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Canzan F, Heilemann MV, Saiani L, Mortari L, Ambrosi E. Visible and invisible caring in nursing from the perspectives of patients and nurses in the gerontological context. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2014;28(4):732–740. doi: 10.1111/scs.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SM, Littler M. Justifying knowledge, justifying methods, taking action: Epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(10):1316–1328. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP 2013) 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Oxford: CASP; 2013. Retrieved from http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Chan CW, Lopez V. A qualitative descriptive study of risk reduction for coronary disease among the Hong Kong Chinese. Public Health Nursing. 2014;31(4):327–335. doi: 10.1111/phn.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YJ, Tsai YF, Lee SH, Lee HL. Protective factors against suicide among young-old Chinese outpatients. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:372. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland LM, Bonugli R. Experiences of mothers of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome in the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2014;43(3):318–329. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JM, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons and evaluation criteria. Qualitative Sociology. 1990;13(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- DeBruyn RR, Ochoa-Marin SC, Semenic S. Barriers and facilitators to evidence-based nursing in Colombia: perspectives of nurse educators, nurse researchers and graduate students. Investigación y Educación en Enfermería. 2014;32(1):9–21. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v32n1a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The Discipline and practice of qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ewens B, Chapman R, Tulloch A, Hendricks JM. ICU survivors' utilisation of diaries post discharge: a qualitative descriptive study. Australian Critical Care. 2014;27(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantasia HC, Sutherland MA, Fontenot H, Ierardi JA. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about contraceptive and sexual consent negotiation among college women. Journal of Forensic Nursing. 2014;10(4):199–207. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friman A, Wahlberg AC, Mattiasson AC, Ebbeskog B. District nurses' knowledge development in wound management: ongoing learning without organizational support. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2014;15(4):386–395. doi: 10.1017/S1463423613000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaughan V, Logan D, Sethna N, Mott S. Parents' perspective of their journey caring for a child with chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Management Nursing. 2014;15(1):246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley M. The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education. 2007;30(3):287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hart PL, Mareno N. Cultural challenges and barriers through the voices of nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014;23(15–16):2223–2232. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasman K, Kjaergaard H, Esbensen BA. Fathers' experience of childbirth when non-progressive labour occurs and augmentation is established. A qualitative study. Sexual & Reproductive HealthCare. 2014;5(2):69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins I, van der Riet P, Sneesby L, Good P. Nutrition and hydration in dying patients: the perceptions of acute care nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014;23(17–18):2609–2617. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland ML, Christensen JJ, Shone LP, Kearney MH, Kitzman HJ. Women's reasons for attrition from a nurse home visiting program. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2014;43(1):61–70. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson M, Hildingsson I, Fenwick J. 'As long as they are safe--birth mode does not matter' Swedish fathers' experiences of decision-making around caesarean section. Women and Birth. 2014;27(3):208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao MH, Tsai YF. Illness experiences in middle-aged adults with early-stage knee osteoarthritis: findings from a qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014;70(7):1564–1572. doi: 10.1111/jan.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawulich BB. Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2005;6(2) Art. 43. Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/466/997. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr D, McKay K, Klim S, Kelly AM, McCann T. Attitudes of emergency department patients about handover at the bedside. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014;23(11–12):1685–1693. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneck A, Fagerberg I, Eriksson LE, Lundman B. Living with diabetes - development of learning patterns over a 3-year period. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2014;9:24375. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v9.24375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Larocque N, Schotsman C, Kaasalainen S, Crawshaw D, McAiney C, Brazil E. Using a book chat to improve attitudes and perceptions of long-term care staff about dementia. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2014;40(5):46–52. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20140110-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li IC, Lee SY, Chen CY, Jeng YQ, Chen YC. Facilitators and barriers to effective smoking cessation: counselling services for inpatients from nurse-counsellors' perspectives--a qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11(5):4782–4798. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110504782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lux KM, Hutcheson JB, Peden AR. Ending disruptive behavior: staff nurse recommendations to nurse educators. Nurse Education in Practice. 2014;14(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Zlatnik MG, Maxfield DG, Lewis A, McMillan C, Kennedy HP. Contributions of clinical disconnections and unresolved conflict to failures in intrapartum safety. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2014;43(1):2–12. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F, Li J, Liang H, Bai Y, Song J. Baccalaureate nursing students' perspectives on learning about caring in China: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Medical Education. 2014;14:42. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L. A humanbecoming qualitative descriptive study on quality of life with older adults. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2014;27(2):132–141. doi: 10.1177/0894318414522656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinowicz L, Abramowicz P, Zarzycka D, Abramowicz M, Konstantynowicz J. How hospitalized children and parents perceive nurses and hospital amenities: A qualitative descriptive study in Poland. Journal of Child Health Care. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1367493514551313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorella G, Boitor M, Michaud C, Gelinas C. Feasibility and acceptability of hand massage therapy for pain management of postoperative cardiac surgery patients in the intensive care unit. Heart & Lung. 2014;43(5):437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough A, Callans KM, Carroll DL. Understanding the challenges during transitions of care for children with critical airway conditions. ORL Head and Neck Nursing. 2014;32(4):12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGilton KS, Boscart VM, Brown M, Bowers B. Making tradeoffs between the reasons to leave and reasons to stay employed in long-term care homes: perspectives of licensed nursing staff. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2014;51(6):917–926. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael N, O'Callaghan C, Baird A, Hiscock N, Clayton J. Cancer caregivers advocate a patient- and family-centered approach to advance care planning. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2014;47(6):1064–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Patient-centered outcomes in older adults with epilepsy. Seizure. 2014;23(8):592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne J, Oberle K. Enhancing rigor in qualitative description: a case study. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2005;32(6):413–420. doi: 10.1097/00152192-200511000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, Sondergaard J. Qualitative description - the poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2009;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea MF. Staff nurses' perceptions regarding palliative care for hospitalized older adults. The American Journal of Nursing. 2014;114(11):26–34. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000456424.02398.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterveld-Vlug MG, Pasman HR, van Gennip IE, Muller MT, Willems DL, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Dignity and the factors that influence it according to nursing home residents: a qualitative interview study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014;70(1):97–106. doi: 10.1111/jan.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oruche UM, Draucker C, Alkhattab H, Knopf A, Mazurcyk J. Interventions for family members of adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2014;27(3):99–108. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parse RR. Qualitative inquiry: The path of sciencing. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Barlett; 2001. [Google Scholar]