Abstract

Background

Higher body mass index (BMI) is associated with incident colorectal cancer (CRC) but not consistently with CRC survival. Whether weight gain or loss is associated with CRC survival is largely unknown.

Methods

We identified 2,781 patients from Kaiser Permanente Northern California diagnosed with stages I-III CRC between 2006-2011 with weight and height measurements within 3 months of diagnosis and ~18 months post diagnosis. We evaluated associations between weight change and CRC-specific and overall mortality, adjusted for sociodemographics, disease severity, and treatment.

Results

Following completion of treatment and recovery from stage I-III CRC, loss of at least 10% of baseline weight was associated with significantly worse CRC-specific mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 3.20; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.33-4.39; P trend <0.0001) and overall mortality (HR 3.27; 95% CI, 2.56-4.18; P trend <0.0001). For every 5% loss of baseline weight, there was a 41% increased risk of CRC-specific mortality (95% CI, 29%-56%). Weight gain was not significantly associated with CRC-specific mortality (P trend=0.54) or overall mortality (P trend=0.27). The associations were largely unchanged after restricting analyses to exclude patients who died within 6 months and 12 months of the second weight measurement. No significant interactions were demonstrated for weight loss or gain by gender, stage, primary tumor location, or baseline BMI.

Conclusions

Weight loss after diagnosis was associated with worse CRC-specific mortality and overall mortality. Reverse causation does not appear to explain our findings.

Impact

Understanding mechanistic underpinnings for the association of weight to worse mortality is important to improving patient outcomes.

Keywords: Body mass index, weight change, survival, mortality, colorectal cancer

INTRODUCTION

Higher body mass index (BMI) has been associated with the risk of many cancer types.(1) In a systematic review of studies examining the association between BMI and the risk of colorectal cancer, with inclusion of over seven million subjects and over 93,000 cases, having a BMI of 23.0-24.9, 25.0-27.4, 27.5-29.9 and ≥ 30.0 kilogram (kg)/meter(m)2 was associated with 14%, 19%, 24% and 41% increased risks of developing CRC (CRC), compared to BMI <23 kg/m2. (2) The impact of excess adiposity on outcomes in CRC survivors has been less certain. Prospective observational cohort studies in colon and/or rectal cancer survivors have only shown a modest association with outcomes. (3-13) When detected, the association has primarily been restricted to those with BMI ≥ 35 mg/m2 (class II and III obesity), with approximately 25% worse disease-free survival.(6, 7, 9, 13) Further, some studies have demonstrated a U-shaped curve with potential optimal BMI in the overweight range.(14) Studies have also varied in timing of ascertainment of exposure (prior to diagnosis, at diagnosis and after diagnosis/surgery).(15)

Once diagnosed with CRC, patients seek to know what actions can be taken to improve their outcomes, including changes to diet, level of exercise and weight. While many patients and providers assume that losing weight if overweight or obese would be beneficial and weight gain would be detrimental towards their cancer outcomes, few studies have examined weight change in CRC survivors.(16) In contrast, the breast cancer literature has several studies testing the association with change in weight and outcomes, with gain in weight associated with increased risk of recurrence and/or mortality in some (17-20) but not others (21-23) studies; furthermore, many of those studies have shown that large weight loss may also increase risk of recurrence and/or mortality.

Using electronic medical record (EMR) data collected as a part of standard clinical care, where weight and height were routinely measured at clinic visits, within Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), we sought to examine change in weight from diagnosis to approximately 18 months after diagnosis and the associations with CRC-specific and overall mortality. Given that KPNC is an integrated health care delivery system and patients receive all of their clinical care within the system, we derived the largest observational cohort to date of stage I – III CRC survivors with availability of multiple weight measurements as well as annotated demographics, tumor characteristics and treatment data.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Study Population

The study cohort was derived from the KPNC cancer registry with ascertainment of all patients diagnosed with Stage I-III invasive CRC between 2006 and 2011, ages 18-80 with weight and CT imaging around time of diagnosis (as part of a project called C-SCANS; n=3409). This analysis of weight change after diagnosis was derived from the C-SCANS cohort, with the requirement of a baseline weight within 3 months of CRC diagnosis and prior to surgery and a follow-up weight approximately 18 months after diagnosis (range 15-21). Of the 3,409 patients in the C-SCANS cohort, 2,781 had weight measurements meeting these timing criteria. The study was approved by the KPNC institutional review board.

Data Collection

Percent Weight Change

Height and weight were measured and input to the EMR by medical assistants using standard procedures in the clinical practices of KPNC. BMI was computed in kilograms per meter squared. Change in weight was calculated by subtracting at diagnosis weight from weight after diagnosis and percentage change was calculated by dividing that weight difference by at diagnosis weight and multiplied by 100 (median time between 2 weight measures = 17.9 months [range 12.7 - 23.0 months]). We created categories of weight change by intervals of 5% (large loss ≥10%, moderate loss 5-9.9%, stable (−4.9 to +4.9%), modest gain 5-9.9%, large gain ≥10%).

Clinical variables and endpoints

We obtained information on prognostic factors, including disease stage, tumor characteristics, and receipt of chemotherapy or radiation from the KPNC Cancer Registry and the medical record. In addition, sociodemographics from the EMR were extracted and considered in multivariate models. Data on CRC-specific and overall mortality were obtained from the KPNC computerized mortality file, which is comprised of data from the California State Department of Vital Statistics, U.S. Social Security Administration, and KPNC utilization data sources. Deaths were considered “CRC-specific” if CRC was listed as a cause of death on the death certificate.

Statistical analysis

We used age-adjusted and multivariate-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models to examine associations between percent weight change and CRC-specific and overall mortality. Time was computed from the time of the follow-up weight measure to time of event or study end. To address possible reverse causality, we conducted sensitivity analyses, eliminating deaths occurring within 6 months and 12 months of the second weight measurement as well as considered “early” events (within 3 years of the second weight measurement) separately from later deaths.

In determining potential confounders in our regression model, we examined variables associated with CRC-specific mortality outcomes in previous epidemiologic studies and those suggested in preliminary analyses. Generally, inclusion of potential confounders in our final regression models were evaluated based on comparison of the regression coefficients both adjusted and unadjusted for the potential confounder under consideration, including the confounder if one or more of the regression coefficients changes by ≥10%. The proportional hazards assumption was met testing by Wald chi-square (P values: 0.67 for CRC-mortality and 0.73 for overall mortality). Restricted cubic splines were fitted to test the non-linear relationship of weight change and CRC survival.

We conducted analyses stratified by stage, BMI, site of primary tumor, gender, and age. Interactions were tested in a model with the main effect, the covariate of interest and a cross-product of the two. P-value reported is a Wald chi-square test. We also conducted tests of proportionality with variable by time interactions. Tests of statistical significance were two-sided. Significant results denote p-values ≤ 0.05 and were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.(24)

RESULTS

At KPNC, 2,781 patients diagnosed with stage I, II or III CRC between 2006 and 2011 were identified meeting cohort entry criteria. Of the 2,781 CRC patients, 549 died of any cause and 311 died of CRC, with median follow-up of 4.2 years (range 0.1-8.1 years), based on last update of death records through June 15, 2015.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics by percent weight change from diagnosis to follow-up are shown in Table 1. When compared to the overall cohort distribution of baseline characteristics, subjects that had large weight loss (≥10%) were more commonly female, stage III, had poorly differentiated tumors, had rectal primary tumors, and received chemotherapy and/or radiation. By contrast, those with large weight gain (≥10%) were more commonly stage II and III, had proximal colon cancer and received chemotherapy.

Table 1. Selected characteristics according to categories of percentage weight change in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California population of colorectal cancer patients diagnosed from 2006-2011 (N=2,781).

| % Weight Change (range 15-21 months post diagnosis) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Loss (≥10%) |

Modest Loss (5-9.9%) |

Stable (−4.9-4.9%) |

Modest Gain (5-9.9%) |

Large Gain (≥10%) |

Overall | |

| N | 239 | 309 | 1460 | 453 | 320 | 2781 |

| Median change(kg) | −14.0 | −6.8 | 0.0 | 7.0 | 14.2 | 1.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Median Age at Diagnosis (Years) | ||||||

| 63 | 64 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 63 | |

| Sex (%) | ||||||

| Female | 62.8 | 55.0 | 47.3 | 51.2 | 49.4 | 50.4 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| White | 71.8 | 65.7 | 65.1 | 65.1 | 61.3 | 65.3 |

| Black | 7.6 | 5.5 | 8.0 | 5.3 | 7.5 | 7.2 |

| Hispanic | 10.1 | 11.0 | 10.2 | 12.6 | 14.7 | 11.2 |

| Asian | 10.1 | 16.5 | 16.3 | 16.8 | 15.6 | 15.8 |

| Other | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| BMI at Baseline (%), kg/m2 | ||||||

| <25 | 22.2 | 29.5 | 30.5 | 35.1 | 47.2 | 32.4 |

| 25-<30 | 31.8 | 38.8 | 36.2 | 39.5 | 32.5 | 36.2 |

| 30-<35 | 22.2 | 19.7 | 21.0 | 17.7 | 15.3 | 19.7 |

| >=35 | 23.8 | 12.0 | 12.3 | 7.7 | 5.0 | 11.7 |

| BMI at Follow-up (%), kg/m2 | ||||||

| <25 | 53.1 | 45.0 | 29.8 | 23.6 | 17.8 | 31.1 |

| 25-<30 | 26.4 | 31.7 | 36.5 | 38.2 | 32.2 | 34.9 |

| 30-<35 | 11.7 | 16.5 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 31.9 | 21.5 |

| >=35 | 8.8 | 6.8 | 12.2 | 15.7 | 18.1 | 12.5 |

| Tumor Stage (%) | ||||||

| I | 20.1 | 28.2 | 32.9 | 27.4 | 17.8 | 28.7 |

| II | 28.5 | 31.4 | 29.9 | 37.1 | 39.1 | 32.1 |

| III | 51.5 | 40.5 | 37.2 | 35.5 | 43.1 | 39.2 |

| Grade of differentiation (%) | ||||||

| Well | 7.1 | 3.6 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 7.2 | 6.8 |

| Moderate | 66.9 | 80.9 | 78.4 | 73.7 | 76.3 | 76.7 |

| Poor | 20.1 | 11.7 | 10.5 | 12.1 | 12.2 | 11.9 |

| Undifferentiated | 5.9 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 4.7 |

| Missing | 7.1 | 3.6 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 7.2 | 6.8 |

| Site of Primary Cancer (%) | ||||||

| Proximal | 43.1 | 43.4 | 42.1 | 49.9 | 51.6 | 44.7 |

| Distal | 17.6 | 21.4 | 28.4 | 26.5 | 25.9 | 26.1 |

| Rectal | 39.3 | 35.3 | 29.5 | 23.6 | 22.5 | 29.2 |

| Treatment (%) | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | 61.7 | 49.7 | 44.7 | 44.8 | 52.5 | 47.6 |

| Radiation | 29.0 | 22.7 | 14.9 | 13.2 | 13.4 | 16.5 |

Percent Weight Change and Outcomes

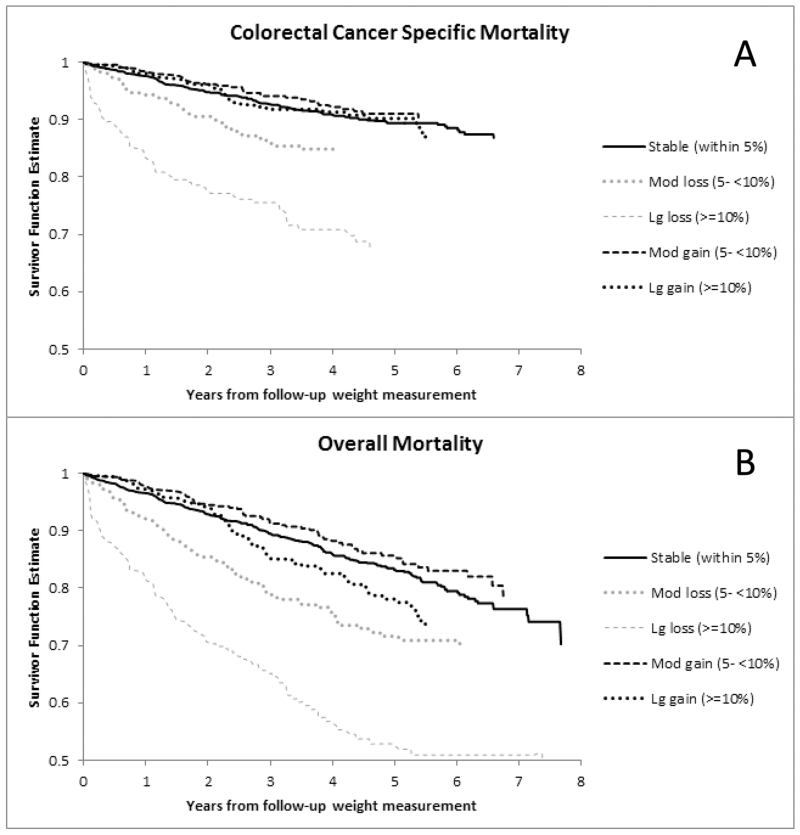

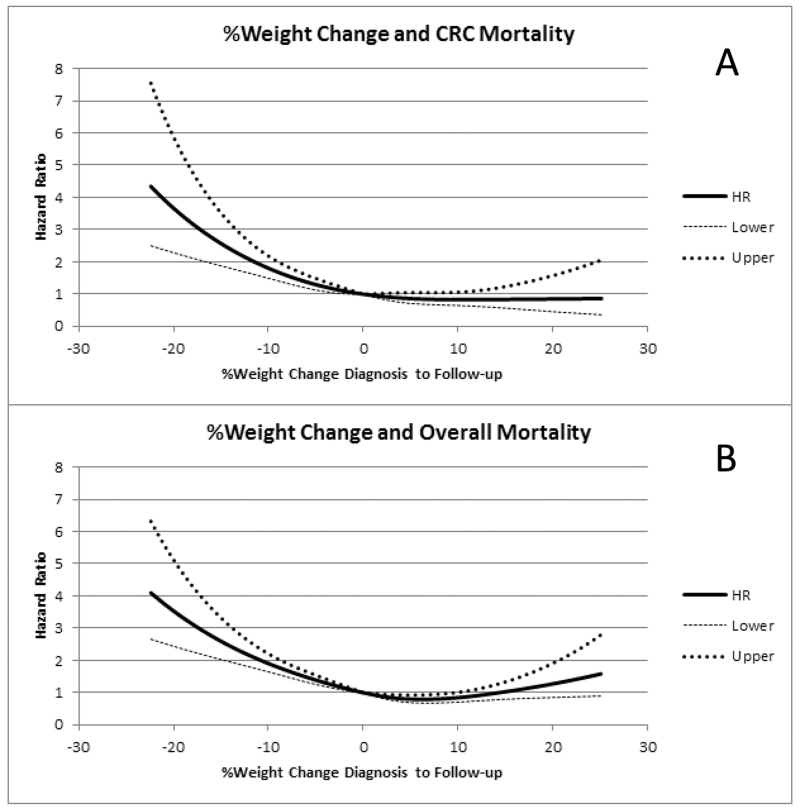

In models adjusted for age, gender, and race, CRC-specific mortality was significantly associated with both large and modest weight loss (P trend < 0.0001) and overall mortality was significantly associated with both large and modest weight loss (P trend < 0.0001), while weight gain was not associated with any mortality outcomes (Table 2). After adjustment for other potential confounders (stage, grade of differentiation, site of primary tumor, receipt of chemotherapy or radiation therapy and baseline weight), weight loss remained significantly associated with CRC-specific mortality (HR 1.58; 95% CI 1.12-2.23 with moderate loss and HR 3.20; 95% CI 2.33-4.39 with large loss; P trend < 0.0001). In categorical analysis, large and moderate weight losses were also significantly associated with overall mortality (HR 3.27; 95% CI 2.56-4.18 and HR 1.74; 95% CI 1.34-2.25, respectively; P trend < 0.0001 in fully adjusted models). In contrast, weight gain was not associated with CRC-specific mortality (P trend = 0.54) nor overall mortality (P trend = 0.27). Figure 1 demonstrates unadjusted survival curves for these categories while Figure 2 provides adjusted spline curve representations of continuous weight change as function of hazard. For every 2% loss in weight, there was a 15% increase in CRC-specific mortality (95% CI, 11%-19%). Additionally, for every 5% loss in weight there was a 41% increase in CRC-specific mortality (95% CI, 29%-56%). Consideration of BMI change did not demonstrate any meaningfully different observations, when BMI loss was associated with worse CRC-specific and overall mortality while BMI gain was not associated with outcomes (data not shown).

Table 2. Weight Change and Survival: Diagnosis to Follow-up.

| % Weight Change [Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Large Loss (≥10%) |

Modest Loss (5-9.9%) |

Stable (−4.9-4.9%) |

Modest Gain (5-9.9%) |

Large Gain (≥10%) |

P Loss | P Gain | |

| Colorectal Cancer Specific-Mortality | |||||||

| # Events / At risk | 65/239 | 43/309 | 136/1460 | 35/453 | 32/320 | ||

| Minimally Adjusted * | 3.82 (2.83-5.15) | 1.66 (1.18-2.35) | Referent | 0.83 (0.57-1.20) | 1.09 (0.74-1.60) | <0.0001 | 0.26 |

| Fully Adjusted ** | 3.20 (2.33-4.39) | 1.58 (1.12-2.23) | Referent | 0.84 (0.58-1.22) | 0.93 (0.63-1.37) | <0.0001 | 0.54 |

| Overall Mortality | |||||||

| # Events / At risk | 104/239 | 79/309 | 235/1460 | 63/453 | 68/320 | ||

| Minimally Adjusted * | 3.59 (2.84-4.53) | 1.76 (1.36-2.27) | Referent | 0.85 (0.64-1.12) | 1.33 (1.01-1.74) | <0.0001 | 0.11 |

| Fully Adjusted ** | 3.27 (2.56-4.18) | 1.74 (1.34-2.25) | Referent | 0.86 (0.65-1.14) | 1.20 (0.91-1.58) | <0.0001 | 0.27 |

|

|

|||||||

Adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), gender, and race

Adjusted for age and weight at diagnosis (continuous), gender (female versus male), race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic or Asian versus non-Hispanic white), stage (II or III versus I), grade (moderate or poorly/undifferentiated versus well differentiated), chemotherapy (not received versus received), radiation therapy (not received versus received), and cancer site (colon versus rectal).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier curves for Colorectal Cancer Specific Death (A) and Overall Mortality (B) by Categories of Percentage Weight Change Within 3 months Diagnosis (prior to surgery) and 15-21 months After Diagnosis

Figure 2.

Adjusted Spline curves for Colorectal Cancer Specific Death (A) and Overall Mortality (B) as Continuous Percentage Weight Change Within 3 months Diagnosis (prior to surgery) and 15-21 months after diagnosis

In sensitivity analyses to address the potential for significant weight loss portending imminent death, we restricted analyses to patients alive at least 6 months after the second weight measurement (excluding 55 patients). Weight loss remained significantly associated with CRC-specific mortality (Ptrend = <0.0001) and overall mortality (Ptrend < 0.0001). Weight gain was not significantly associated with CRC-specific mortality (Ptrend = 0.34) or overall mortality (Ptrend = 0.12). Results were similar when we further excluded deaths that occurred within 12 months of the second weight measurement (excluding 117 patients). Weight loss predicted higher CRC-specific (Ptrend =0.003) and overall mortality (Ptrend < 0.0001), and weight gain was not associated with CRC-specific mortality (Ptrend = 0.42), though was borderline-associated with overall mortality (Ptrend = 0.08).

We considered mortality bias in our analyses. The associations we observed for large weight loss remained unchanged when limiting outcomes to within first three years after follow-up weight or only considered outcomes beyond three years after follow-up weight. For example, in analyses of CRC-specific mortality, large weight loss had an associated HR 3.71 (95% CI, 2.61-5.29) when restricting analyses to only events within first 3 years and a HR 2.39 (1.14-5.01) when restricting analyses to only events that occur beyond first 3 years. No significant associations were observed with weight gain in similar analyses by time of event.

Stratified analyses

In stratified analyses, there were no apparent differences by gender, site of primary tumor, stage of disease, smoking status, presence or absense of significant comorbidities, baseline BMI or receipt of chemotherapy (all P interactions > 0.05) for weight loss. There was a significant association for age for weight loss and overall mortality (P interaction =0.03) though the direction of the associations were similar for below and above median age. Two subgroup analyses for weight loss were of particular interest, by stage at diagnosis and baseline BMI (Table 3). Despite the number of events being low in stage I disease, there was consistency of point estimates for large weight loss for each stage of disease in both CRC-specific (P interaction = 0.95) and overall mortality (P interaction = 0.48). Similarly, regardless of baseline BMI, large weight loss was associated with worse CRC-specific mortality (P interaction = 0.96) and overall mortality (Pinteraction = 0.69).

Table 3. Multivariate Adjusted Weight Loss and Survival by Stage and Baseline BMI: Diagnosis to Follow-up.

| # Events |

Large Loss (≥10%) |

Modest Loss (5-9.9%) |

Stable (−4.9-4.9%) |

P Loss | P interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer Specific-Mortality | ||||||

| Stage I (N=797) | 24 | 6.76 (1.93-23.6) | 1.63 (0.44-6.02) | Referent | 0.03 | |

| Stage II (N=894) | 72 | 2.42 (1.19-4.93) | 1.48 (0.72-3.07) | Referent | 0.01 | |

| Stage III (N=1090) | 215 | 3.44 (2.37-5.00) | 1.59 (1.05-2.41) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.95 |

| BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 (N=835) | 93 | 3.22 (1.67-6.23) | 1.46 (0.77-2.78) | Referent | 0.01 | |

| BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2 (N=1014) | 106 | 3.72 (2.17-6.39) | 1.66 (0.91-3.00) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (N=889) | 103 | 2.68 (1.62-4.43) | 1.30 (0.68-2.51) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.96 |

| Chemotherapy (N=1315) | 219 | 3.02 (2.10-4.35) | 1.28 (0.83-1.97) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| No Chemotherapy (N=1447) | 88 | 4.07 (2.14-7.74) | 2.44 (1.35-4.43) | Referent | 0.0001 | 0.19 |

| Age <63 (N=1392) | 154 | 3.76 (2.39-5.92) | 1.41 (0.82-2.42) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Age >=63 (N=1389) | 157 | 2.94 (1.89-4.58) | 1.74 (1.10-2.74) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.63 |

| Men (N=1380) | 154 | 3.54 (2.19-5.73) | 1.33 (0.78-2.26) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.45 |

| Women (N=1401) | 157 | 2.96 (1.93-4.52) | 1.81 (1.14-2.87) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Colon (N=1969) | 208 | 3.67 (2.48-5.45) | 1.33 (0.84-2.11) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.21 |

| Rectal (N=812) | 103 | 2.98 (1.75-5.06) | 2.17 (1.26-3.76) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Smoking-Never (N=1307) | 129 | 2.31 (1.33-4.00) | 1.55 (0.94-2.58) | Referent | 0.003 | 0.55 |

| Smoking-Former (N=1149) | 138 | 3.87 (2.45-6.13) | 1.84 (1.10-3.07) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Smoking-Current (N=322) | 44 | 5.21 (2.08-13.02) | 0.72 (0.16-3.31) | Referent | 0.003 | |

| No significant comorbidities (N=1941) |

196 | 2.94 (1.97-4.38) |

1.47 (0.94-2.28) |

Referent | <0.0001 | 0.89 |

| Significant comorbidities at diagnosis (N=840) |

115 | 3.76 (2.23-6.34) | 1.80 (1.02-3.17) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Overall Mortality | ||||||

| Stage I (N=797) | 87 | 6.01 (3.16-11.4) | 2.34 (1.23-4.46) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Stage II (N=894) | 168 | 2.17 (1.34-3.51) | 1.36 (0.83-2.23) | Referent | 0.0001 | |

| Stage III (N=1090) | 294 | 3.50 (2.52-4.85) | 1.80 (1.27-2.55) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.48 |

| BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 (N=835) | 164 | 4.20 (2.58-6.85) | 1.50 (0.91-2.48) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2 (N=1014) | 193 | 3.17 (2.07-4.84) | 2.22 (1.47-3.35) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (N=889) | 176 | 2.83 (1.91-4.20) | 1.31 (0.80-2.15) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.69 |

| Chemotherapy (N=1315) | 296 | 3.05 (2.22-4.17) | 1.36 (0.94-1.96) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| No Chemotherapy (N=1447) | 247 | 3.72 (2.51-5.52) | 2.27 (1.57-3.27) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.09 |

| Age <63 (N=1392) | 212 | 4.14 (2.83-6.04) | 1.21 (0.74-1.98) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Age >=63 (N=1389) | 337 | 2.98 (2.16-4.16) | 2.12 (1.56-2.88) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.03 |

| Men (N=1380) | 285 | 3.40 (2.35-4.91) | 1.84 (1.27-2.65) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.85 |

| Women (N=1401) | 264 | 2.98 (2.13-4.16) | 1.54 (1.07-2.21) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Colon (N=1969) | 389 | 3.76 (2.79-5.07) | 1.58 (1.14-2.19) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.12 |

| Rectal (N=812) | 160 | 2.64 (1.71-4.08) | 2.12 (1.37-3.28) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Smoking-Never (N=1307) | 199 | 2.23 (1.39-3.59) | 1.55 (1.03-2.34) | Referent | 0.0001 | 0.41 |

| Smoking-Former (N=1149) | 264 | 3.80 (2.69-5.38) | 2.07 (1.44-2.98) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| Smoking-Current (N=322) | 85 | 6.12 (3.16-11.83) | 1.30 (0.51-3.29) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

| No significant comorbidities (N=1941) |

298 | 2.68 (1.90-3.78) | 1.42 (0.98-2.05) | Referent | <0.0001 | 0.43 |

| Significant comorbidities at diagnosis (N=840) |

251 | 3.90 (2.73-5.57) | 2.04 (1.41-2.94) | Referent | <0.0001 | |

Adjusted for age and weight at diagnosis (continuous), gender (female versus male), race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic or Asian versus non-Hispanic white), stage (II or III versus I), grade (moderate or poorly/undifferentiated versus well differentiated), chemotherapy (not received versus received), radiation therapy (not received versus received), and cancer site (colon versus rectal).

Weight gain was not significantly associated with CRC-specific mortality or overall mortality in any specific subset of the cohort by demographics or tumor characteristics (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In a population-based cohort housed within an integrated health care delivery system, patients with stage I-III CRC who lost ≥10% weight within 18 months after diagnosis experienced significantly increased risks of CRC-specific and overall mortality. This association was significant regardless of disease stage at diagnosis and whether patients were initially normal weight, overweight or obese. This association further persisted in sensitivity analyses considering reverse causation by restricting the examination to patients not having an event within 6 months and 12 months of the second weight measurement. In contrast, weight gain was not associated with CRC-specific mortality or overall mortality.

The KPNC cohort in this study is the largest to date to test association of weight change after CRC diagnosis with outcomes, allowing for more robust subgroup analyses. To our knowledge, only 3 other studies have reported on change in weight and mortality in CRC survivors. (7)(12)(25) Baade and colleagues ascertained weight and height prior to diagnosis, 5 months and 12 months after diagnosis in a population-based study of stage I-III CRC survivors in Queensland, Australia. (25) Weight loss was significantly associated with increased CRC-specific and overall mortality when considering change in weight prior to diagnosis and 5 months post-diagnosis, as well as change from 5 and 12 months post-diagnosis. Weight gain between pre-diagnosis and 5 months post-diagnosis was associated with increased risk of CRC-specific mortality (HR 1.63, 95% CI 1.02-2.61) but not overall mortality; however, neither CRC-specific nor overall mortality was significantly related to weight gain from 5-12 months post diagnosis. Similarly, Campbell et. al. reported significant associations between weight loss from pre-diagnosis to post-diagnosis and increased risk of CRC-specific and overall mortality but not weight gain in the Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort.(12) Meyerhardt and colleagues similarly found significant associations with worse disease-free and overall survival for weight loss (greater than 5 kg) but not weight gain between weights at time of initiation of chemotherapy to 15 months after completion of chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer patients participating in a National Cancer Institute-sponsored adjuvant chemotherapy trial.(7) Our study confirms these findings in a larger, population-based dataset including patients with stage I – III disease and evaluated by baseline (at diagnosis) BMI. The advantage of our study is use of a baseline clinic-measured weight within 3 months of diagnosis and prior to surgery, a measure truly reflective of the patient’s adiposity at diagnosis (prior studies either utilized recall weight prior to diagnosis,(25) self-report weights years prior to diagnosis (12) or post surgery weight (7)).

While it is not known if weight loss after diagnosis is intended or unintentional, a key question is whether weight loss is a marker of disease progression or whether it influences the disease outcome. An assumption of prior reports is that the association of weight loss with increased CRC-specific and overall mortality is due to reverse causality. While this may in part be true, several observations in our data suggest additional potential explanations for our findings. First, the results remained largely unchanged even after excluding patients who died within 6 months and 12 months of the post diagnosis weight measurement. Second, the effects are apparent even among Stage 1 disease. Finally, weight loss in the first 18 months post-diagnosis is still associated with poor survival for deaths occurring later in the survival period (> 3 years post diagnosis). One potential explanation is that weight loss is frequently accompanied by loss of muscle mass and may lead to sarcopenia (ie. muscle depletion independent of adiposity). (26, 27) This may be especially pertinent to CRC survivors since at diagnosis approximately 35% of this population is already at risk for poor survival based on their low muscle level (unpublished data) and weight loss likely leads to further decreases in muscle mass. Adequate muscle mass, and possibly greater muscle mass than noncancer patients, has been shown to be a strong determinant of overall mortality in several studies of cancer patients. (28-39) Studies of CRC patients with advanced disease found that muscle wasting was associated with worse recurrence-free and/or overall survival(40) as well as poor response to chemotherapy.(41) Persons with low muscle mass experience elevated low-grade systemic inflammation,(42) and altered mitochondrial function,(43, 44) both of which may influence cancer progression . Additionally because skeletal muscle is primarily responsible for insulin-mediated glucose uptake and disposal, progressive loss of muscle mass may promote insulin resistance(45-47) which in of itself has been related to poorer outcomes in cancer survivors.(48) It has also been demonstrated that tumor growth, inactivity post surgery and chemotherapy may all lead to proteolysis, further supporting the requirement for adequate muscle mass.(49, 50) Furthermore, loss of muscle mass typically results in a decrease in physical activity(42) and there are now a number of studies that physically active colorectal cancer survivors have improved outcomes,(51) hypothesized to be related improvements in hyperinsulinemia and/or insulin sensitivity, reduced inflammation or alteration in vitamin D levels and metabolism. Thus, several potential mechanistic pathways, all pointing to weight loss potentiating the risk of sarcopenia, may explain our findings. Nonetheless, the role of fat loss in this population is less clear particularly since there are different types of fat with potentially different roles on cancer survival in the context of weight loss.(52-55)

The lack of interaction between weight loss and baseline BMI suggests that even weight loss in obese patients may not necessarily have a positive effect. It is nonetheless important to consider that recent evidence in several chronic conditions including cancer, suggests that having a high BMI has no protective effect in the presence of sarcopenia, and that it is the latter condition rather than adipose tissue that associates with poor prognosis.(56) While we observed no interaction by BMI, the magnitude of risk was substantially less for the obese (who in general have more muscle mass) than the normal weight and overweight, also suggesting that considering muscle mass status before weight loss may be important . Therefore, the apparent “obesity paradox” may instead represent a “BMI paradox”(57) confounded by the lack of distinctive contributions of muscle versus adiposity tissue on survival outcomes. Future body composition studies are needed to clarify our findings. Additionally, while this dataset cannot determine etiology of weight loss, it demonstrates that weight loss in the first 18 months post-diagnosis is not infrequent (~20%) and it leads one to reconsider automatically advising weight loss in obese and overweight CRC patients in the immediate post-diagnosis period without understanding who will lose weight or the mechanisms underlying weight loss and mortality, and influences of muscle mass status. Further research should examine whether weight loss in the more distant post-diagnosis period may have beneficial effects.

The lack of association with weight gain and outcomes may have several possible explanations. One argument supporting the negative impact of weight gain in women with breast cancer is that weight gain leads to increases in circulating estrogens.(58) In CRC survivors, increased estrogen may be protective, as seen in an analysis of hormone replacement therapy in survivors.(59) Alternatively, while other factors related to energy balance have been implicated in outcomes of colorectal cancer survivors, including physical inactivity, high Western pattern diet and diets high in glycemic load and sugar sweetened beverages, (60) studies have not consistently demonstrated association between weight or BMI and outcomes in colorectal cancer survivors.(15, 61) Therefore, similarly one would not necessarily expect weight gain after diagnosis to negatively impact patient survival. Finally, gain in adipose tissue may have mixed effects on prognosis depending on distribution of fat, as shown in a recent study in gastric cancer in which subcutaneous fat was associated with an improved survival while visceral fat was associated with a worse survival.(62)

There are strengths and limitations in this study that should be considered when interpreting the findings. KPNC represents a diverse integrated health care delivery system with use of clinical pathways to standardize patient care. KPNC represents approximately 30% of the California insured population and is highly representative except at the very lowest end of the socioeconomic spectrum.(63) Thus, compared to cohorts derived from clinical trials, this population should be more generalizable to the overall CRC population. Use of the EMR allows for prospective data collection, avoiding recall biases. However, the EMR lacks comprehensive data on patient factors that may be associated with the exposure of interest, including diet and physical activity as well as measures of fraility. While the current KPNC EMR does not allow for accurate determination of exact time of cancer recurrence, and weight loss could be related to undocumented recurrences, the vast majority of CRC survivors who develop recurrent disease die of the disease and, thus, CRC-specific mortality should be a reasonable surrogate of recurrence.

In conclusion, loss of weight approximately one year after diagnosis is associated with worse CRC-specific mortality and overall mortality whereas gain was not associated with outcomes in CRC survivors. While reverse causality may partially explain these findings, other potential explanations warrant further research as therapeutic interventions may be needed if sarcopenia or inadequate muscle mass is a mechanism underlying this association. Ongoing efforts in this cohort are measuring muscle mass from computer tomography scans to examine associations of baseline body composition and change in body composition on outcomes.

Financial Support/Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA175011 to B. J. Caan and R01 CA149222 to J.A. Meyerhardt.). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health or Kaiser Permanent Northern California.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ning Y, Wang L, Giovannucci EL. A quantitative analysis of body mass index and colorectal cancer: findings from 56 observational studies. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2010;11:19–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tartter PI, Slater G, Papatestas AE, Aufses AH., Jr. Cholesterol, weight, height, Quetelet’s index, and colon cancer recurrence. J Surg Oncol. 1984;27:232–5. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930270407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyerhardt JA, Catalano PJ, Haller DG, Mayer RJ, Benson AB, 3rd, Macdonald JS, et al. Influence of body mass index on outcomes and treatment-related toxicity in patients with colon carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:484–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyerhardt JA, Tepper JE, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis DR, McCollum AD, Brady D, et al. Impact of body mass index on outcomes and treatment-related toxicity in patients with stage II and III rectal cancer: findings from Intergroup Trial 0114. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:648–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dignam JJ, Polite BN, Yothers G, Raich P, Colangelo L, O’Connell MJ, et al. Body mass index and outcomes in patients who receive adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1647–54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Nelson H, et al. Impact of body mass index and weight change after treatment on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4109–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hines R, Shanmugam C, Waterbor J, McGwin G, Funkhouser E, Coffey C, et al. Effect of Comorbidity and Body Mass Index on the Survival of African-American and Caucasian Patients With Colon Cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:5798–806. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Sargent DJ, O’Connell MJ, Rankin C. Obesity is an independent prognostic variable in colon cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1884–93. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuiper JG, Phipps AI, Neuhouser ML, Chlebowski RT, Thomson CA, Irwin ML, et al. Recreational physical activity, body mass index, and survival in women with colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1939–48. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin CC, Kuo YH, Yeh CY, Chen JS, Tang R, Changchien CR, et al. Role of body mass index in colon cancer patients in Taiwan. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4191–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell PT, Newton CC, Dehal AN, Jacobs EJ, Patel AV, Gapstur SM. Impact of body mass index on survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis: the Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:42–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Yothers G, Benson A, Seitz JF, Labianca R, et al. Body mass index at diagnosis and survival among colon cancer patients enrolled in clinical trials of adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2013;119:1528–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renehan AG. The ‘obesity paradox’ and survival after colorectal cancer: true or false? Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2014;25:1419–22. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0436-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkin E, O’Reilly DA, Sherlock DJ, Manoharan P, Renehan AG. Excess adiposity and survival in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2014;15:434–51. doi: 10.1111/obr.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otto SJ, Korfage IJ, Polinder S, van der Heide A, de Vries E, Rietjens JA, et al. Association of change in physical activity and body weight with quality of life and mortality in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke CH, Chen WY, Rosner B, Holmes MD. Weight, weight gain, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1370–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camoriano JK, Loprinzi CL, Ingle JN, Therneau TM, Krook JE, Veeder MH. Weight change in women treated with adjuvant therapy or observed following mastectomy for node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1327–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.8.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fedele P, Orlando L, Schiavone P, Quaranta A, Lapolla AM, De Pasquale M, et al. BMI variation increases recurrence risk in women with early-stage breast cancer. Future oncology. 2014;10:2459–68. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thivat E, Therondel S, Lapirot O, Abrial C, Gimbergues P, Gadea E, et al. Weight change during chemotherapy changes the prognosis in non metastatic breast cancer for the worse. BMC cancer. 2010;10:648. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caan BJ, Emond JA, Natarajan L, Castillo A, Gunderson EP, Habel L, et al. Post-diagnosis weight gain and breast cancer recurrence in women with early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99:47–57. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9179-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caan BJ, Kwan ML, Hartzell G, Castillo A, Slattery ML, Sternfeld B, et al. Pre-diagnosis body mass index, post-diagnosis weight change, and prognosis among women with early stage breast cancer. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2008;19:1319–28. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeon YW, Lim ST, Choi HJ, Suh YJ. Weight change and its impact on prognosis after adjuvant TAC (docetaxel-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy in Korean women with node-positive breast cancer. Medical oncology. 2014;31:849. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1:43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baade PD, Meng X, Youl PH, Aitken JF, Dunn J, Chambers SK. The impact of body mass index and physical activity on mortality among patients with colorectal cancer in Queensland, Australia. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2011;20:1410–20. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cederholm TE, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Rolland Y. Toward a definition of sarcopenia. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2011;27:341–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rolland Y, Abellan van Kan G, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Vellas B. Cachexia versus sarcopenia. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2011;14:15–21. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328340c2c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukushima H, Yokoyama M, Nakanishi Y, Tobisu K, Koga F. Sarcopenia as a prognostic biomarker of advanced urothelial carcinoma. PloS one. 2015;10:e0115895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iritani S, Imai K, Takai K, Hanai T, Ideta T, Miyazaki T, et al. Skeletal muscle depletion is an independent prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of gastroenterology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0964-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanic H, Kraut-Tauzia J, Modzelewski R, Clatot F, Mareschal S, Picquenot JM, et al. Sarcopenia is an independent prognostic factor in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2014;55:817–23. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.816421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyamoto Y, Baba Y, Sakamoto Y, Ohuchi M, Tokunaga R, Kurashige J, et al. Sarcopenia is a Negative Prognostic Factor After Curative Resection of Colorectal Cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2015 doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozola Zalite I, Zykus R, Francisco Gonzalez M, Saygili F, Pukitis A, Gaujoux S, et al. Influence of cachexia and sarcopenia on survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A systematic review. Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parsons HA, Baracos VE, Dhillon N, Hong DS, Kurzrock R. Body composition, symptoms, and survival in advanced cancer patients referred to a phase I service. PloS one. 2012;7:e29330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng P, Hyder O, Firoozmand A, Kneuertz P, Schulick RD, Huang D, et al. Impact of sarcopenia on outcomes following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2012;16:1478–86. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1923-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng PD, van Vledder MG, Tsai S, de Jong MC, Makary M, Ng J, et al. Sarcopenia negatively impacts short-term outcomes in patients undergoing hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastasis. HPB : the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2011;13:439–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Psutka SP, Carrasco A, Schmit GD, Moynagh MR, Boorjian SA, Frank I, et al. Sarcopenia in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy: impact on cancer-specific and all-cause mortality. Cancer. 2014;120:2910–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith AB, Deal AM, Yu H, Boyd B, Matthews J, Wallen EM, et al. Sarcopenia as a predictor of complications and survival following radical cystectomy. The Journal of urology. 2014;191:1714–20. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Vledder MG, Levolger S, Ayez N, Verhoef C, Tran TC, Ijzermans JN. Body composition and outcome in patients undergoing resection of colorectal liver metastases. The British journal of surgery. 2012;99:550–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voron T, Tselikas L, Pietrasz D, Pigneur F, Laurent A, Compagnon P, et al. Sarcopenia Impacts on Short- and Long-term Results of Hepatectomy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Annals of surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyamoto Y, Baba Y, Sakamoto Y, Ohuchi M, Tokunaga R, Kurashige J, et al. Negative Impact of Skeletal Muscle Loss after Systemic Chemotherapy in Patients with Unresectable Colorectal Cancer. PloS one. 2015;10:e0129742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barret M, Antoun S, Dalban C, Malka D, Mansourbakht T, Zaanan A, et al. Sarcopenia is linked to treatment toxicity in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Nutrition and cancer. 2014;66:583–9. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.894103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roubenoff R. Physical activity, inflammation, and muscle loss. Nutrition reviews. 2007;65:S208–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calvani R, Joseph AM, Adhihetty PJ, Miccheli A, Bossola M, Leeuwenburgh C, et al. Mitochondrial pathways in sarcopenia of aging and disuse muscle atrophy. Biological chemistry. 2013;394:393–414. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marzetti E, Calvani R, Cesari M, Buford TW, Lorenzi M, Behnke BJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and sarcopenia of aging: from signaling pathways to clinical trials. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2013;45:2288–301. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guillet C, Boirie Y. Insulin resistance: a contributing factor to age-related muscle mass loss? Diabetes & metabolism. 2005;31(Spec No 2):5S20–5S6. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(05)73648-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kohara K. Sarcopenic obesity in aging population: current status and future directions for research. Endocrine. 2014;45:15–25. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-9992-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srikanthan P, Hevener AL, Karlamangla AS. Sarcopenia exacerbates obesity-associated insulin resistance and dysglycemia: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. PloS one. 2010;5:e10805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sridhar SS, Goodwin PJ. Insulin-insulin-like growth factor axis and colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:165–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melstrom LG, Melstrom KA, Jr., Ding XZ, Adrian TE. Mechanisms of skeletal muscle degradation and its therapy in cancer cachexia. Histology and histopathology. 2007;22:805–14. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith KL, Tisdale MJ. Increased protein degradation and decreased protein synthesis in skeletal muscle during cancer cachexia. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:680–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Je Y, Jeon JY, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA. Association between physical activity and mortality in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1905–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsoli M, Schweiger M, Vanniasinghe AS, Painter A, Zechner R, Clarke S, et al. Depletion of white adipose tissue in cancer cachexia syndrome is associated with inflammatory signaling and disrupted circadian regulation. PloS one. 2014;9:e92966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murphy KT, Struk A, Malcontenti-Wilson C, Christophi C, Lynch GS. Physiological characterization of a mouse model of cachexia in colorectal liver metastases. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2013;304:R854–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00057.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy RA, Wilke MS, Perrine M, Pawlowicz M, Mourtzakis M, Lieffers JR, et al. Loss of adipose tissue and plasma phospholipids: relationship to survival in advanced cancer patients. Clinical nutrition. 2010;29:482–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kliewer KL, Ke JY, Tian M, Cole RM, Andridge RR, Belury MA. Adipose tissue lipolysis and energy metabolism in early cancer cachexia in mice. Cancer biology & therapy. 2015;16:886–97. doi: 10.4161/15384047.2014.987075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonzalez MC, Pastore CA, Orlandi SP, Heymsfield SB. Obesity paradox in cancer: new insights provided by body composition. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2014;99:999–1005. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.071399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bozorgmanesh M, Arshi B, Sheikholeslami F, Azizi F, Hadaegh F. No Obesity Paradox-BMI Incapable of Adequately Capturing the Relation of Obesity with All-Cause Mortality: An Inception Diabetes Cohort Study. International journal of endocrinology. 2014;2014:282089. doi: 10.1155/2014/282089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cleary MP, Grossmann ME. Minireview: Obesity and breast cancer: the estrogen connection. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2537–42. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan JA, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS. Hormone replacement therapy and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5680–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee J, Jeon JY, Meyerhardt JA. Diet and lifestyle in survivors of colorectal cancer. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2015;29:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schlesinger S, Siegert S, Koch M, Walter J, Heits N, Hinz S, et al. Postdiagnosis body mass index and risk of mortality in colorectal cancer survivors: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2014;25:1407–18. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li XT, Tang L, Chen Y, Li YL, Zhang XP, Sun YS. Visceral and subcutaneous fat as new independent predictive factors of survival in locally advanced gastric carcinoma patients treated with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2015;141:1237–47. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1893-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gordon NP. Similarity of the Adult Kaiser Permanente Membership in Northern California to the Insured and General Population in Northern California: Statistics from the 2011 California Health Interview Survey. Feb 8, 2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]