Abstract

Although the human liver comprises approximately 2.8% of the body weight, it plays a central role in the control of energy metabolism. While the biochemistry of energy substrates such as glucose, fatty acids, and ketone bodies in the liver is well understood, many aspects of the overall control system for hepatic metabolism remain largely unknown. These include mechanisms underlying the ascertainment of its energy metabolism status by the liver, and the way in which this information is used to communicate and function together with adipose tissues and other organs involved in energy metabolism.

This review article summarizes hepatic control of energy metabolism via the autonomic nervous system.

Keywords: Autonomic nerves, Energy metabolism, Liver, Adipose tissue, Lipolysis

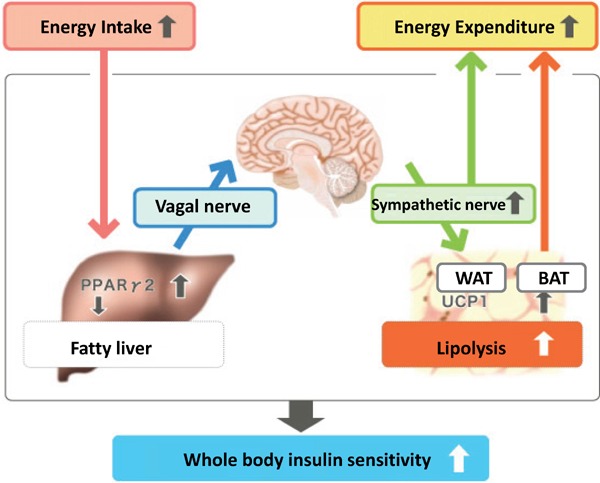

In 2006, Katagiri et al. of Tohoku University reported in Science Magazine the existence of a liver-brain-adipose-neural axis (Fig. 1)1). They discovered a control mechanism wherein when there is an excess accumulation of neutral fat in the liver (i.e., fatty liver), the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve sends signals to break down fats; after passing through the liver-brain-adipose-neural axis, these signals finally activate the sympathetic nervous system to enhance lipolysis in white adipose tissue.

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of accelerated lipolysis in fatty liver diseases

Cited from: Yamada T. Inter-organ communications mediate crosstalk between glucose and energy metabolism. (Review) Diabetol Int. 4(3): 149–155. 2013

This important discovery proved that with hyperalimentation, afferent nerve signals (vagal nerve signals) transmitted by hepatic proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) accelerate lipolysis and energy consumption, and contribute to the maintenance of body-weight homeostasis during the amelioration of diabetes.

Hepatic-origin Autonomic Nervous System Signaling with Glycogen Depletion

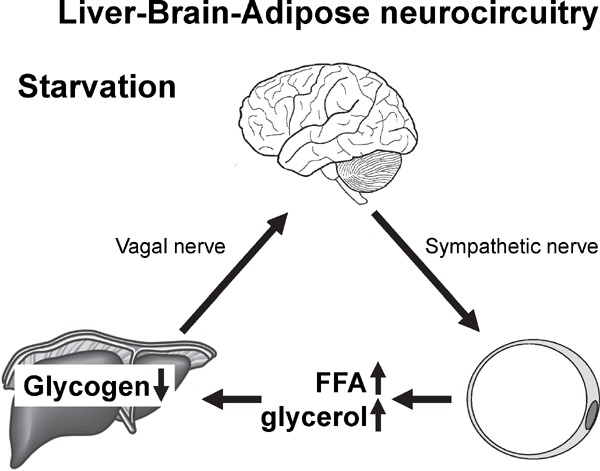

After the discovery of the liver-brain-adipose-neural axis, we sought to learn more about the related physiological functions of this pathway. Fig. 2 shows our finding that this neural axis plays an important role in fat mobilization during fasting2).

Fig. 2.

Glycogen shortage during fasting triggers liver.brain.

adipose neurocircuitry to facilitate fat utilization Cited from; Izumida Y et al: Glycogen shortage during fasting triggers liver-brain-adipose neurocircuitry to facilitate fat utilization. Nat Commun. 2013; 4: 2316.

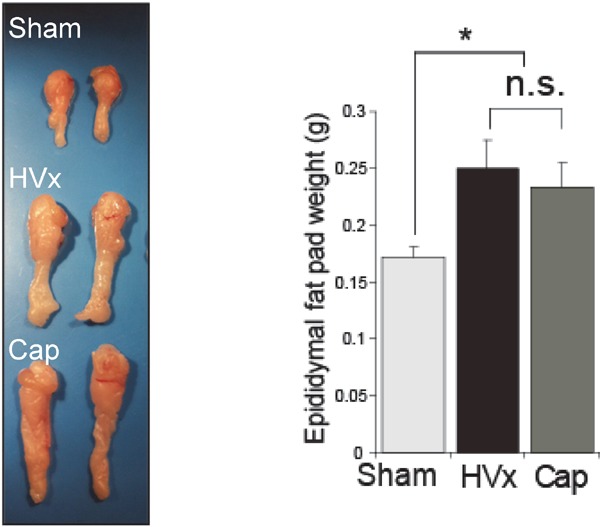

When the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve is surgically removed (hepatic vagotomy, HVx), the decline in visceral fat (epididymal-area fat) during fasting becomes moderate (Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained even when the ascending neuronal path of the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve was interrupted by capsaicin (Cap). Notably, effects on adipose tissue were limited only to visceral fat; no effects were seen for subcutaneous fat. Whole-body changes in energy metabolism were analyzed using gas expiration analysis. Although no differences were observed for oxygen consumption rates, significant differences were observed for respiratory quotient (RQ) and fat utilization rates, with the hepatic vagotomy group (HVx group) showing reduced fat utilization during fasting.

Fig. 3.

Selective HVx preserves fasting fat pad mass

Cited from; Izumida Y et al: Glycogen shortage during fasting triggers liver-brain-adipose neurocircuitry to facilitate fat utilization. Nat Commun. 2013; 4: 2316.

For adipose tissue, promoted lipolysis caused by the activation of sympathetic nerve pathways was observed; we were able to visualize a significant decline in cAMP signals in the HVx group using an in vivo imaging system, wherein cAMP signaling—the intracellular second messenger in sympathetic nerve activation— was visualized by luminescence.

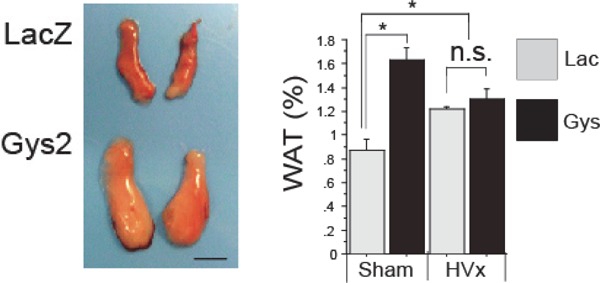

Further, detailed investigation of temporal changes in the output of hepatic-origin fasting-response neuronal signals revealed that differences between the HVx and control group (Sham group) started occurring at the same time when glycogen storage was depleting. We observed that when the overexpression of glycogen synthase 2 (Gys2) was induced using adenovirus and glycogen was preloaded, lipolysis was suppressed, and the difference between the two groups was canceled by the HVx (Fig. 4). Conversely, when the Gys2 was knocked down by RNA interference, the decrease in liver glycogen content caused further acceleration of lipolysis during fasting.

Fig. 4.

Hepatic glycogen loading cancels liver.brain.adipose axis activation

Cited from; Izumida Y et al: Glycogen shortage during fasting triggers liver-brain-adipose neurocircuitry to facilitate fat utilization.

Nat Commun. 2013; 4: 2316.

The next question we addressed was how the decline in stored glycogen was recognized within the liver. In particular, we wondered whether the depletion of glycogen itself could be detected, or a decline in the quantity of glycogen degradation products (e.g., glucose-1-phosphate) had to be detected. To determine this, we performed RNA interference on a glycogen phosphorylase liver-type gene (Pygl); adenoviral shRNA (Pygl-i) was expressed in the liver, which targets Pygl. When glycogenolysis was suppressed by this RNA interference, the liver glycogen content was elevated and this in turn led to a decrease in lipolysis in the adipose tissue. This result demonstrates that the shortage of glycogen, but not that of the downstream metabolites, is the key to triggering the neurocircuitry. Thus, the glycogen quantity itself, and not the glycogen degradation product should be monitored.

These experimental results revealed that glycogen storage levels in the liver are monitored by some kind of mechanism. When glycogen stores are nearly depleted during starvation, the liver-brain-adiposeneural axis is activated and fat utilization is accelerated; thereby, the energy source shifts from carbohydrates to fats.

Hepatic-origin Autonomic Nervous System Signals with Excess Glucose and Amino Acids

In addition to their analysis of hepatic-origin autonomic nervous system signals after accumulation of excessive fatty acids, Katagiri et al. analyzed and recently reported the effects of neuronal signals on white and brown adipose tissue after excessive glucose uptake, and after excessive uptake of amino acids (AAs) by the liver3, 4).

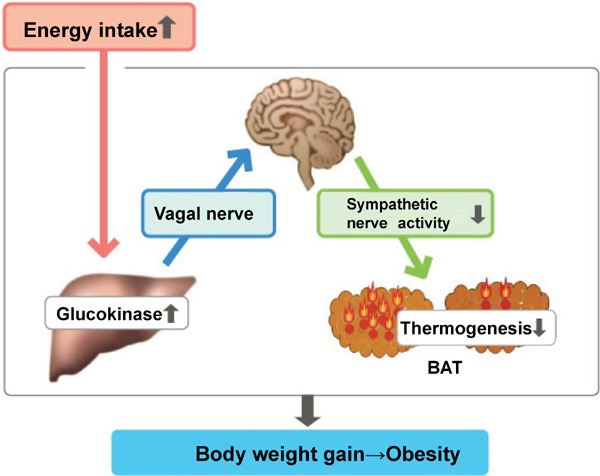

According to their report, when there is an excess of hepatic glucose uptake, neural modulation suppresses thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue (BAT) (Fig. 5). That is, when there is excessive glucokinase expression in the liver that accelerates glucose uptake, changes in glycometabolism occur in the liver. Signals elicited from these changes are communicated via vagal afferent nerves, which when received, reduce sympathetic nervous activity from the medulla oblongata to BAT; thermogenesis in BAT is suppressed, and fat accumulation is accelerated. This mechanism is considered responsible for reduced energy consumption in response to increased energy uptake. From this perspective, it can be considered as an economizing mechanism at the individual organism level.

Fig. 5.

Hepatic glucokinase modulates obesity predisposition by regulating BAT thermogenesis via neural signals

Cited from: Yamada T. Inter-organ communications mediate crosstalk between glucose and energy metabolism. (Review) Diabetol Int. 4(3): 149–155. 2013

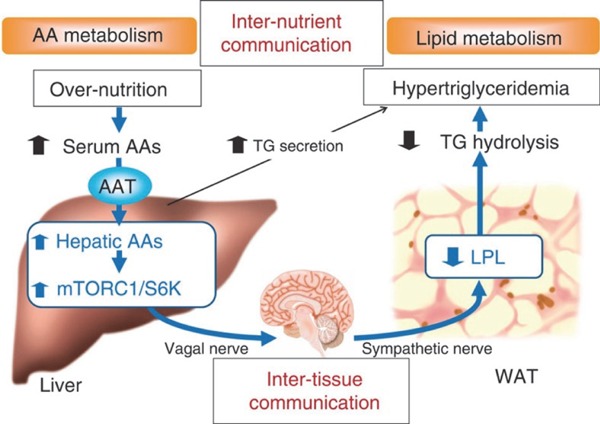

When the same method is used to induce excess hepatic expression of SNAT2, an AA transporter, an unexpected result was a marked presentation of hypertriglyceridemia (Fig. 6)4). Excess AA uptake in the liver activates mTORC1/S6K, and neuronal signals originating from there pass through the hepatic branch of the vagus-brain-sympathetic nerve axis; this in turn was found to suppress adipocyte lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and triglyceride degradation in the blood.

Fig. 6.

link between hepatic AA metabolism and WAT function

Cited from; Imai J et al: Regulation of pancreatic beta cell mass by neuronal signals from the liver. Science 2008; 322: 1250-1254.

Although hyperalimentation is considered to lead to hyperlipidemia, it is now clear that autonomic regulation is one of the involved mechanisms.

Conclusions

Katagiri et al. have also reported that hepatic activation of extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) signaling induced pancreatic beta cell proliferation5); these signals were also relayed along the hepatic branch of the vagus-brain-sympathetic nerve axis.

Conventionally, organs involved in energy metabolism such as the liver, adipose tissue, etc., are considered to be linked, and work together via humoral factors such as insulin and glucagon. In reality, however, stored energy quantities within each of these organs fluctuate temporally. Linking these organs so that they can effectively function together, as described above, fine-tuning the regulatory mechanisms mediated via the autonomic nervous system plays an essential role.

Although nerve signals have been shown to be essential in regulating energy metabolism, the actual natures of these nerve signals are still unknown. Further research to comprehend these nerve signals is essential for the entire spectrum of knowledge, from understanding their mechanisms, to using this information for therapeutic applications.

References

- 1). Uno K, Katagiri H, Yamada T, Ishigaki Y, Ogihara T, Imai J, Hasegawa Y, Gao J, Kaneko K, Iwasaki H, Ishihara H, Sasano H, Inukai K, Mizuguchi H, Asano T, Shiota M, Nakazato M, Oka Y: Neuronal pathway from the liver modulates energy expenditure and systemic insulin sensitivity. Science 2006; 312: 1656-1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Izumida Y, Yahagi N, Takeuchi Y, Nishi M, Shikama A, Takarada A, Masuda Y, Kubota M, Matsuzaka T, Nakagawa Y, Iizuka Y, Itaka K, Kataoka K, Shioda S, Niijima A, Yamada T, Katagiri H, Nagai R, Yamada N, Kadowaki T, Shimano H: Glycogen shortage during fasting triggers liver-brain-adipose neurocircuitry to facilitate fat utilization. Nat Commun. 2013; 4: 2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Tsukita S, Yamada T, Uno K, Takahashi K, Kaneko K, Ishigaki Y, Imai J, Hasegawa Y, Sawada S, Ishihara H, Oka Y, Katagiri H: Hepatic glucokinase modulates obesity predisposition by regulating BAT thermogenesis via neural signals. Cell Metab. 2012; 16: 825-832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Uno K, Yamada T, Ishigaki Y, Imai J, Hasegawa Y, Sawada S, Kaneko K, Ono H, Asano T, Oka Y, Katagiri H: A hepatic amino acid/mTOR/S6K-dependent signalling pathway modulates systemic lipid metabolism via neuronal signals. Nat Commun. 2015; 6: 7940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Imai J, Katagiri H, Yamada T, Ishigaki Y, Suzuki T, Kudo H, Uno K, Hasegawa Y, Gao J, Kaneko K, Ishihara H, Niijima A, Nakazato M, Asano T, Minokoshi Y, Oka Y: Regulation of pancreatic beta cell mass by neuronal signals from the liver. Science 2008; 322: 1250-1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]