Abstract

Aim: We investigated the safety and efficacy of a long-term combination therapy with fenofibrate and ezetimibe in Japanese patients with combined hyperlipidemia, in comparison with fenofibrate or ezetimibe alone.

Methods: The study was a three-arm parallel-group, open-label randomized trial. Eligible patients were assigned to a combination therapy with fenofibrate (200 mg/day in capsule form or 160 mg/day in tablet form) and ezetimibe (10 mg/day), the fenofibrate monotherapy, or the ezetimibe monotherapy, which lasted for 52 weeks. The changes in serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides were the primary outcomes.

Results: A total of 236 patients were assigned to one of the three treatments, and the number of patients included in the final analysis was 107 in the combination therapy, 52 in the fenofibrate monotherapy, and 51 in the ezetimibe monotherapy. Mean ± SD changes in LDL cholesterol were −24.2% ± 14.7% with combination therapy, −16.0% ± 16.0% with fenofibrate alone, and −17.4% ± 10.1% with ezetimibe alone. The combination therapy resulted in a significantly greater reduction in LDL cholesterol as compared with each monotherapy (p < 0.01 for each). The corresponding values for triglycerides were −40.0% ± 29.5%, −40.1% ± 28.7%, and −3.4% ± 32.6%, respectively. Fenofibrate use was associated with some changes in laboratory measurements, but there was no differential adverse effect between the combination therapy and fenofibrate monotherapy.

Conclusion: The combination therapy with fenofibrate and ezetimibe substantially reduces concentrations of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides and is safe in a long-term treatment in Japanese patients with combined hyperlipidemia.

Keywords: Combined hyperlipidemia, LDL cholesterol, Triglycerides, Fenofibrate, Ezetimibe

Introduction

Combined hyperlipidemia is characterized by elevated concentrations of serum cholesterol and triglycerides (TG). The most important element in lipid management is satisfactory reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). However, TG is also independently associated with cardiovascular events, and the combined hyperlipidemia is related to an elevated risk of cardiovascular diseases. More recently, hypertriglyceridemia is reported to predict the development of diabetes in non-obese patients1). Thus, the intensive therapy for combined hyperlipidemia is important.

Generally, combined hyperlipidemia is treated with statin and fibrate, with statin and nicotinic acid derivative in combination, or with fibrate alone2). Although statin–fibrate combination therapy provides potent effects, such treatment may increase the risk of rhabdomyolysis3). Therefore, a more effective and safer drug regimen has been sought for treating patients with combined hyperlipidemia. The desired regimen would allow the use of fibrates, which are highly effective in lowering TG, in combination with a non-statin agent.

The fibrate, fenofibrate, reduces LDL-C concentration by 18%–25%4–6). Although this reduction is not as great as that achieved with strong statins, fenofibrate also reduces TG by 40%–48% and increases high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) by 35%–36%, which improves the overall lipid profile4–6). Results from most of the intervention studies (such as DAIS and FIELD) have shown that fenofibrate inhibits macrovascular events, such as coronary artery disease and microvascular events, in diabetic patients7, 8).

Ezetimibe, a new cholesterol-absorption inhibitor is widely used in Japan, reduces LDL-C by approximately 18%. In a recent large-scale clinical study, cardiovascular events were reduced by 2.0% with ezetimibe plus statin than with statin alone (32.7% and 34.7% incidence in the statin–ezetimibe group and statin-only group, respectively)9).

The present study was a three-group randomized study in patients with combined hyperlipidemia to compare the efficacy of a long-term combination therapy with fenofibrate and ezetimibe and also to compare the safety of this combination therapy with fenofibrate alone or ezetimibe alone.

Aim

To determine the efficacy and long-term safety of combination therapy with fenofibrate and ezetimibe in comparison with fenofibrate alone and ezetimibe alone in patients with combined hyperlipidemia.

Methods

Patients

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible patients were men and women aged between 20 and 75 years at the time of obtaining informed consent. Patients were required to have a TG concentration of 200–400 mg/dL and LDL-C concentration of ≥140 mg/dL as calculated by the Friedewald formula10) at screening, in accordance with the 2007 Guidelines for Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases11).

Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria at entry: 1) use of probucol within the previous year; 2) familial hypercholesterolemia; 3) drug-induced hyperlipidemia from steroids or other drugs; 4) history or complication of malignant tumor, pancreatitis, gallstones, gallbladder disease, drug abuse, alcoholism, recent myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular disorder (within 3 months before the study), cardiac arrhythmia requiring drug treatment, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, or serious liver or renal disorder; 5) drug hypersensitivity including history of hypersensitivity to fenofibrate or ezetimibe; 6) problems related to discontinuing prohibited drugs; 7) patients who were pregnant, lactating, possibly pregnant, or planning to become pregnant; 8) participation in other clinical research such as clinical trials; 9) condition successfully controlled by current anti-hyperlipidemic drug; 10) participation otherwise judged inappropriate by the study physicians. Patients were also excluded if the screening tests resulted in a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of ≥8%, aspartate amino-transferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations twice the upper limits of the institutional reference range or ≥ 80 IU/L, or serum creatinine level of ≥ 1.5 mg/dL.

Study Design

This study was a three-arm parallel-group, open-label randomized trial enrolling patients at 50 study centers throughout Japan. Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1:1 ratio to one of three therapies (combination therapy with fenofibrate and ezetimibe, fenofibrate alone, or ezetimibe alone) for 52 weeks. If patients were under medication for dyslipidemia, the study began with a 4-week washout period, which was followed by a 4-week observation period and 52-week treatment period. Treatment-naïve patients did not go through the washout period. During the observation period, patients who had been screened for eligibility were enrolled and randomly assigned. This study was implemented in ordinary outpatient clinics, and the participating physicians used pharmaceutical products available on the market in Japan.

The allocation schedule was created by a data center (Medical Toukei Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Random numbers were generated with the SAS for Windows release 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) statistical software program. A central registration system at the data center was used to ensure that allocation was concealed from other researchers. Dynamic allocation was used to balance the groups on the following six factors: 1) institution (study site); 2) LDL-C concentrations < 160 mg/mL on a screening test at the beginning of the observation period; 3) TG concentrations < 300 mg/mL on a screening test at the beginning of the observation period; 4) sex; 5) age < 65 years; 6) presence or absence of diabetes (diagnosed diabetes or an HbA1c concentration of ≥ 6.2%). A biostatistician created a dynamic allocation algorithm, which was not disclosed to study doctors, study collaborators, or the clinical trial office.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical principles for clinical studies in Japan. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of each participating center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Treatment Regimen

The patients in the combination group received fenofibrate (either 2 capsules of Lipidil® 100 mg/capsule or 2 tablets of Lipidil® 80 mg/tablet) plus ezetimibe (1 tablet of Zetia® 10 mg). The patients in the fenofibrate group received fenofibrate (either 2 capsules of Lipidil® 100 mg/capsule or 2 tablets of Lipidil® 80 mg/tablet). The patients in the ezetimibe group received ezetimibe (1 tablet of Zetia® 10 mg). The study physicians selected either the Lipidil® 100 mg capsule or Lipidil® 80 mg tablet, whichever was already in use at that institution.

All three groups took the study drug once daily, after a meal, for 52 weeks. Generally, the medications were taken after the evening meal. If patients had to take the medications at a time other than after-meal in the evening, they were instructed to take the drug or drugs at the same time throughout the study. The combination therapy patients were instructed to take both study drugs at the same time. Throughout the study, patients continued their normal exercise and diet routines. Adherence to the protocol was ascertained by interview at each visit to the study center.

Outpatient Visits and Laboratory Tests

Outpatient visits were scheduled at the start of treatment period and at 4, 8, 12, 24, and 52 weeks (or at the time of discontinuation). At each visit, serum lipid, HbA1c, and other specified measurements were performed at the central laboratory. Laboratory tests, except the above measurements and physical examination, were performed at each individual study site. In addition to these stipulated visits, patients received a regular examination at least every 3 months so that adverse events could be evaluated.

Endpoints

Samples for the analysis of endpoints were tested at a central laboratory to avoid bias in assessment.

Primary Endpoints

The primary endpoints were the percent changes in LDL-C and TG concentrations. Percent change was calculated as [(mean value during treatment − mean value at baseline)/mean value at baseline] × 100. The mean value at baseline was defined as the mean of values measured at two data points before treatment initiation (generally week −4 and week 0). Mean value during treatment was calculated as the mean of values measured at 3 points in time [generally week 12, week 24, and week 52 (or at discontinuation)].

Secondary Endpoints

The secondary endpoints were the incidence of adverse events, including the incidence of gallstones detected by abdominal ultrasound; the incidence of abnormal findings for safety variables, including laboratory tests and physical examination; and the percent change in HDL-C, calculated as [(mean value during treatment − mean value at baseline)/mean value at baseline] × 100. Abnormal findings for laboratory tests were defined as those values that exceeded the standard range for that institution, as stipulated in the safety criteria with CTCAE Version 4.0 (v4.03: June 14, 2010) (see Supplementary Table 1).

Supplementary Table 1. Definition of abnormal level (items measured at individual study centers).

| Laboratory test | Standard reference range |

|---|---|

| WBC [/µL] | < 3000/µL, ≥2-fold increase from week 0 |

| RBC [104/µL] | 550 × 104/µL, < the lower limit of the reference range |

| Hemoglobin [g/dL] | > 2 g/dL increase above the upper limit of the reference range |

| Hematocrit [g/dL] | Change of ≥ − 10% or + 10% from week 0 |

| Platelet count§ [104/µL] | < 7.5 × 104/µL |

| Leukocyte percent (basophils)§ [%] | — |

| Leukocyte percent (eosinophils)§ [%] | — |

| Leukocyte percent (neutrophils)§ [%] | < 1500/µL |

| Leukocyte percent (lymphocytes)§ [%] | < 800/µL, > 4000 µL |

| Leukocyte percent (monocytes)§ [%] | — |

| Total protein [g/dL] | > 1 g/dL decrease from week 0 |

| Albumin [g/dL] | <3 g/dL |

| Total bilirubin [g/dL] | > 1.5-fold the upper limit of the reference range |

| AST (GOT) [IU/L] | > 3.0-fold the upper limit of the reference range |

| ALT (GPT) [IU/L] | > 3.0-fold the upper limit of the reference range |

| ALP [IU/L] | > 2.5-fold the upper limit of the reference range |

| LDH [IU/L] | > the upper limit of the reference range |

| Cholinesterase [IU/L] | > the upper limit of the reference range |

| gamma-GTP [IU/L] | > the upper limit of the reference range |

| Uric acid [mg/dL] | > the upper limit of the reference range |

| BUN [mg/dL] | — |

| Creatinine [mg/dL] | > 1.5-fold the upper limit of the reference range |

| Na [mEq/L] | < the lower limit or > the upper limit of the reference range |

| Cl [mEq/L] | — |

| K [nEq/L] | > 5.5 mEq, <the lower limit of the reference range |

| Ca [mg/dL] | > 11.5 mg/dL, < 8.0 mg/dL |

| P [mg/dL] | < 2.5 mg/dL |

| Blood glucose [mg/dL] | > 160 mg/dL, < 55 mg/dL |

| CPK [IU/L] | > 2.5-fold the upper limit of the reference range |

| Qualitative urine (glucose) | ≥ ±, + (−is normal) |

| Qualitative urine (protein) | ≥ 2+ |

| Qualitative urine (urobilinogen) | ≥ + |

| Specific gravity | — |

| pH | — |

| Qualitative (occult blood) | ≥ ±, + (−is normal) |

The reference range was based on the definition at each study center.

To be investigated only if abnormalities are noted in WBC.

WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; AST (GOT), aspartate aminotransferase; ALT (GPT), alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; GTP, guanosine 5′-triphosphate; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CPK, creatine phosphokinase

Other Exploratory Endpoints

Exploratory endpoints consisted of the following: 1) percent change in other lipid variables [high-sensitivity assays for lipoprotein lipase (LPL), remnant lipoprotein cholesterol (RemL-C), LDL particle size, HDL particle size, apolipoprotein (apo) A-I, A-II, B, B-48, C-II, C-III, E, and phospholipid hydroperoxide]; 2) non-lipid variables [high-sensitivity assay for C-reactive protein (hsCRP), adiponectin]; 3) percent change in lipid variables in patients with familial combined hyperlipidemia; and 4) trends in concentrations of serum lipid subclasses. The percent change was calculated as [(mean value during treatment − mean value at baseline)/mean value at baseline] × 100 for apo A-I, A-II, B, C-II, C-III and E, or [(measured value at the end of treatment − measured value at baseline)/measured value at baseline] × 100 for high-sensitivity assays for LPL, RemL-C, LDL particle size, HDL particle size, apo B-48, phospholipid hydroperoxide and non-lipid variables.

Statistical Methods

The main analysis set was defined as all eligible patients who received study drug(s) at least once after assignment. Under the assumptions based on the results from the previous trials12–14), a sample size of 120 in the combination group, 60 in the fenofibrate group, and 60 in the ezetimibe group would provide a statistical power of ≥ 90% for both hypotheses of the superiority of the combination to fenofibrate alone and ezetimibe alone. Allowing for a 15% dropout rate, the sample size was thus set at 140 patients in the combination group, 70 patients in the fenofibrate group, and 70 patients in the ezetimibe group. Within-group changes in the parameters were assessed by paired t-test. Between-group differences in mean change of the parameters of the primary interest were assessed using unpaired t-tests. Adjustment for multiple-group comparisons was made using the Hochberg procedure15) by setting a single-sided alpha of 0.025. The percentages of categorical variables for between-group differences were compared using Fisher's exact test. Safety parameters were descriptively summarized for each group and were compared between groups. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS for Windows release 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All reported p values were two-sided.

Results

Patients were enrolled from March 2009 to December 2012, and the study was completed in December 2013. Clinics accounted for 58% of the 31 participating centers and 83.8% of patients were enrolled through clinics.

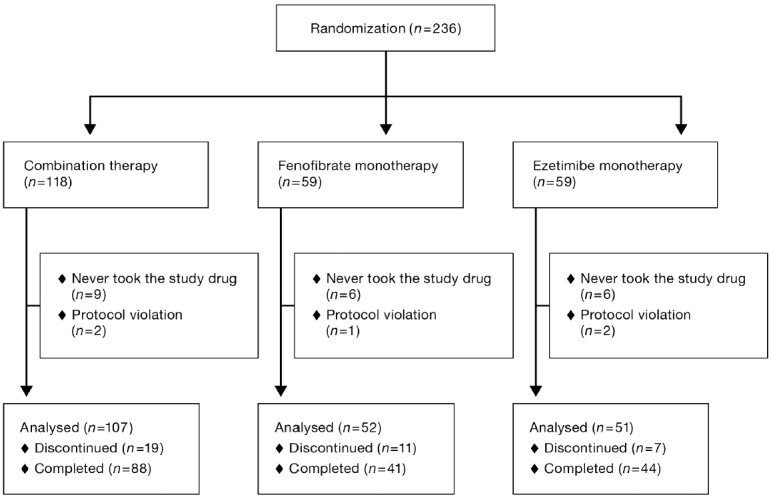

In all, 118 patients were enrolled in the combination group, 59 in the fenofibrate group, and 59 in the ezetimibe group. Of these, 9 patients in the combination group and 6 patients each in the fenofibrate and ezetimibe groups were never treated with the study drug or drugs. Moreover, 2 patients in the combination group, 1 in the fenofibrate group, and 2 in the ezetimibe group were removed for protocol violations because of administration of the wrong study drug for their assigned group, leaving a total sample of 107 patients in the combination group, 52 in the fenofibrate group, and 51 in the ezetimibe group. Of the patients who completed the 52-week treatments, 12 patients were found to have been ineligible (9 in the combination group, 1 in the fenofibrate group, and 2 in the ezetimibe group). These patients were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient enrollment by the study group

Distribution of patient characteristics (sex, age, BMI, prior medical history, complications, and familial combined hyperlipidemia) was well-balanced across the three groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient characteristics at baseline by study group.

| Combination (n = 107) |

Fenofibrate (n = 52) |

Ezetimibe (n = 51) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 63 (58.9) | 31 (59.6) | 29 (56.9) |

| Age, years [mean ± SD] | 55.8 ± 12.6 | 58.3 ± 10.4 | 58.5 ± 10.0 |

| BMI, kg/m2 [mean ± SD] | 27.0 ± 4.4 | 25.2 ± 2.9 | 26.5 ± 3.7 |

| Medical history, n (%) | 7 (6.5) | 3 (5.8) | 4 (7.8) |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Angina, n (%) | 3 (2.8) | 3 (5.8) | 1 (2.0) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other, n (%) | 4 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.8) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 69 (64.5) | 31 (59.6) | 30 (58.8) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 22 (20.6) | 10 (19.2) | 10 (19.6) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 45 (42.1) | 24 (46.2) | 25 (49.0) |

| Thyroid disease, n (%) | 4 (3.7) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (2.0) |

| Other, n (%) | 18 (16.8) | 5 (9.6) | 4 (7.8) |

| Familial combined hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 5 (4.7) | 5 (9.6) | 1 (2.0) |

Drug compliance status was tracked through patient interviews at each clinic. Reponses for the drug use were recorded as “almost all the time,” “about 3/4 of the time,” “about half the time,” or “almost none of the time.” At week 52, the percentage of patients who took the drug “almost all the time” was nearly the same among the three groups (93.1% in the combination therapy group, 89.2% in the fenofibrate group, and 92.1% in the ezetimibe group).

Efficacy

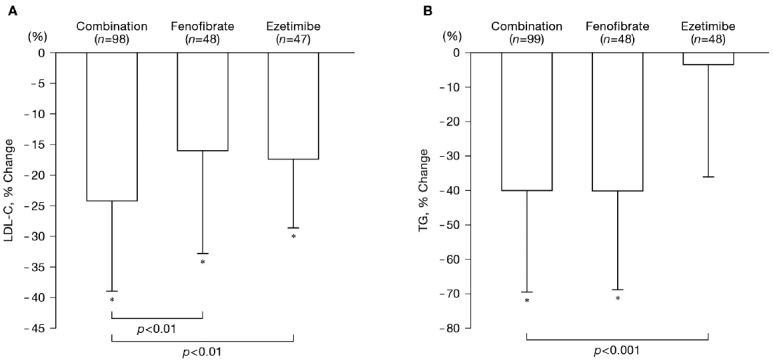

The mean values of percent changes during treatment of LDL-C and TG are shown in Fig. 2. The percent change in LDL-C from baseline was −24.2% ± 14.7% in the combination group, −16.0% ± 16.0% in the fenofibrate group, and −17.4% ± 10.1% in the ezetimibe group; improvement in LDL-C was significantly better in the combination group than in the fenofibrate group or ezetimibe group (p < 0.01). The percent change in TG from baseline was −40.0% ± 29.5% in the combination group, −40.1% ± 28.7% in the fenofibrate group, and −3.4% ± 32.6% in the ezetimibe group; improvement in TG was significantly better in the combination group than in the ezetimibe group (p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Changes in LDL-C and TG during treatment by the study group

The mean value at baseline was defined as the mean of values of week −4 and week 0. Mean value during treatment was calculated as the mean of values of week 12, week 24, and week 52 (or at discontinuation).

*p < 0.05 (vs. Baseline for percent change), by one-sample t-test

p values between treatment groups were single-sided for between-group comparison by two-sample t-test.

LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides

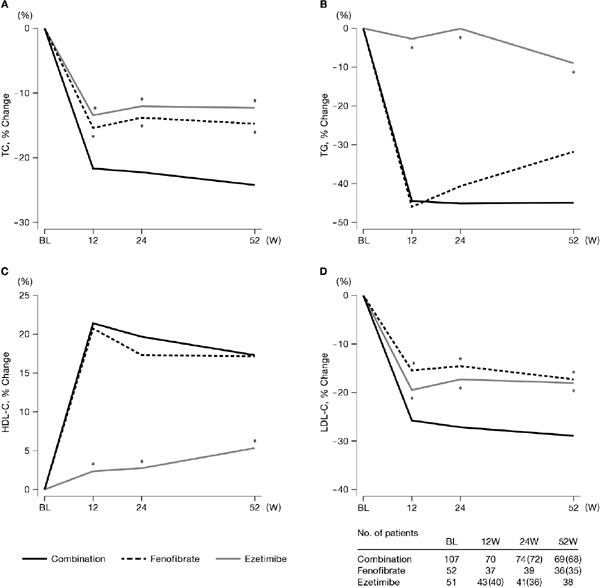

Concentrations of all four lipids [total cholesterol (TC), TG, HDL-C, and LDL-C] at baseline and week 52 and mean percent changes from baseline to week 52 are shown in Table 2. These data were specifically calculated for the percent change between the values at baseline and week 52. Mean LDL-C concentration at 52 weeks was significantly lower in the combination group than in the fenofibrate or ezetimibe group, and mean TG concentration at 52 weeks was also significantly lower in the combination group than in the ezetimibe group (Table 2). Concentrations of all four lipids (TC, TG, HDL-C, and LDL-C) improved significantly from baseline at week 52 in the combination and fenofibrate group. HDL-C remained unchanged in the ezetimibe group. Time course in percent change in TC, LDL-C, TG, and HDL-C are shown in Fig. 3. TC and LDL-C concentrations decreased sharply until week 12 in all three groups, after which the decreased levels were maintained until week 52. TC decreased by 22%–24% in the combination group, by 15% in the fenofibrate group, and by 12%–13% in the ezetimibe group. LDL-C decreased more substantially, i.e., by 26%–29% in the combination group, by 15%–17% in the fenofibrate group, and by 18%–19% in the ezetimibe group. TG concentrations decreased sharply in the combination and fenofibrate groups until week 12 (−44.5% ± 27.0% in the combination group and −46.0% ± 24.0% in the fenofibrate group), after which the concentrations slightly increased in the fenofibrate group, although the decreased levels were sustained in the combination group. The decrease in TG concentrations in the ezetimibe group was not evident. Concentrations of HDL-C increased sharply until week 12 in both the combination (21.4% ± 17.0%) and fenofibrate groups (20.7% ± 19.2%), and the increases were almost stable in both the groups. HDL-C concentration increased modestly in the ezetimibe group, but the change was not statistically significant (Fig. 3).

Table 2. Serum lipid concentrations at baseline and week 52 and percent changes at week 52 by study group.

| Parameters | Combination |

Fenofibrate |

Ezetimibe |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | ||

| TC (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 263 ± 30 | 52 | 268 ± 34 | 51 | 268 ± 28 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 197 ± 28 | 36 | 227 ± 34 | 38 | 233 ± 26 | |

| %Change | 69 | −24.2 ± 10.6* | 36 | −14.8 ± 11.4* | 38 | −12.3 ± 7.9* | |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| TG (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 266 ± 77 | 52 | 266 ± 106 | 51 | 263 ± 107 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 138 ± 74 | 36 | 172 ± 93 | 38 | 224 ± 68 | |

| %Change | 69 | −44.9 ± 27.3* | 36 | −31.8 ± 45.6* | 38 | −9.0 ± 24.7* | |

| p = 0.068 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 47 ± 10 | 52 | 46 ± 10 | 51 | 46 ± 9 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 53 ± 13 | 36 | 51 ± 14 | 38 | 50 ± 16 | |

| %Change | 69 | 17.3 ± 17.5* | 36 | 17.2 ± 23.9* | 38 | 5.3 ± 16.3 | |

| p = 0.972 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 166 ± 27 | 52 | 173 ± 31 | 51 | 171 ± 23 |

| Week 52 | 68 | 117 ± 26 | 35 | 141 ± 29 | 38 | 138 ± 23 | |

| %Change | 68 | −28.9 ± 15.8* | 35 | −17.3 ± 14.3* | 38 | −18.1 ± 11.5* | |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

Mean values at baseline were based on the average of multiple measurements during the pretreatment period (week −4 to week 0).

p values represent the comparison of the percent changes between the combination group and the specified group by two-sample t-test (two-sided).

p < 0.05 for the within-group comparison by one sample t-test.

TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Fig. 3.

Time course of changes in lipid variables by the study group

The mean value at baseline was defined as the mean of values of week −4 and week 0.

Numbers within ( ) indicate number of patients for LDL-C.

*p < 0.05 (vs. Combination for percent change from baseline), two-sided for between-group comparison by two-sample t-test.

TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; BL, baseline

Apolipoproteins followed nearly the same pattern as observed for the four lipids. Particle size increased significantly for LDL and decreased significantly for HDL in the combination and fenofibrate groups, but not in the ezetimibe group. None of the three groups showed any changes in phospholipid hydroperoxide or hsCRP concentration. In the analysis, the individuals' measurements during the treatment were averaged (Table 3).

Table 3. Serum apolipoproteins and lipid-related parameters at base and week 52 and percent changes at 52 weeks by study group.

| Parameters | Combination |

Fenofibrate |

Ezetimibe |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | ||

| Apo A-I (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 137 ± 18 | 52 | 134 ± 18 | 51 | 137 ± 19 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 144 ± 19 | 36 | 141 ± 21 | 38 | 139 ± 29 | |

| %Change | 69 | 7.7 ± 9.1* | 36 | 8.5 ± 13.1* | 38 | 0.9 ± 11.3 | |

| p = 0.702 | p = 0.001 | ||||||

| Apo A-II (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 32 ± 5 | 52 | 30 ± 4 | 51 | 31 ± 4 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 42 ± 9 | 36 | 39 ± 10 | 38 | 31 ± 5 | |

| %Change | 69 | 33.7 ± 25.5* | 36 | 30.1 ± 29.6* | 38 | −0.5 ± 9.3 | |

| p = 0.512 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Apo B (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 130 ± 17 | 52 | 133 ± 20 | 51 | 134 ± 19 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 89 ± 19 | 36 | 105 ± 22 | 38 | 113 ± 13 | |

| %Change | 69 | −31.5 ± 13.1* | 36 | −21.7 ± 14.4* | 38 | −15.2 ± 8.7* | |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Apo B-48 (µg/mL) | Baselinea | 105 | 11.4 ± 7.7 | 52 | 11.0 ± 7.5 | 50 | 10.0 ± 7.0 |

| Week 52 | 67 | 5.1 ± 3.7 | 35 | 6.8 ± 4.8 | 38 | 8.8 ± 5.1 | |

| %Change | 67 | −33.7 ± 56.4* | 35 | −17.9 ± 98.9 | 38 | 5.7 ± 60.4 | |

| p = 0.305 | p = 0.001 | ||||||

| Apo C-II (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 52 | 6.8 ± 1.8 | 51 | 7.1 ± 1.9 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 5.3 ± 1.7 | 36 | 5.8 ± 2.0 | 38 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | |

| %Change | 69 | −20.9 ± 18.9* | 36 | −15.7 ± 23.3* | 38 | −0.2 ± 18.4 | |

| p = 0.220 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Apo C-III (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 14.1 ± 3.2 | 52 | 13.9 ± 3.6 | 51 | 14.4 ± 3.7 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 9.7 ± 3.5 | 36 | 10.6 ± 3.3 | 38 | 13.8 ± 3.9 | |

| %Change | 69 | −29.3 ± 18.2* | 36 | −21.8 ± 24.7* | 38 | −2.2 ± 25.3 | |

| p = 0.081 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Apo E (mg/dL) | Baseline | 107 | 5.2 ± 1.1 | 52 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 51 | 5.2 ± 1.4 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 36 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 38 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | |

| %Change | 69 | −24.1 ± 15.4* | 36 | −18.3 ± 21.0* | 38 | −6.9 ± 18.2* | |

| p = 0.111 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| RemL-C (mg/dL) | Baselinea | 105 | 19.7 ± 11.0 | 52 | 20.2 ± 14.9 | 50 | 20.8 ± 21.5 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 8.3 ± 5.1 | 36 | 12.1 ± 7.2 | 38 | 16.3 ± 6.1 | |

| %Change | 69 | −46.1 ± 37.3* | 36 | −17.4 ± 93.1 | 38 | −3.2 ± 38.8 | |

| p = 0.026 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| LDL particle size | Baselinea | 105 | 25.9 ± 0.6 | 52 | 25.9 ± 0.8 | 49 | 25.8 ± 0.6 |

| (nm) | Week 52 | 69 | 26.7 ± 0.6 | 36 | 26.6 ± 0.6 | 38 | 25.9 ± 0.6 |

| %Change | 69 | 3.4 ± 2.9* | 36 | 3.4 ± 2.8* | 38 | 0.5 ± 2.2 | |

| p = 0.996 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| HDL particle size | Baselinea | 105 | 10.5 ± 0.3 | 52 | 10.5 ± 0.3 | 49 | 10.5 ± 0.3 |

| (nm) | Week 52 | 69 | 10.4 ± 0.2 | 36 | 10.4 ± 0.2 | 38 | 10.5 ± 0.3 |

| %Change | 69 | −0.9 ± 1.8* | 36 | −0.7 ± 1.5* | 38 | 0.4 ± 1.7 | |

| p = 0.712 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Phospholipid | Baselinea | 95 | 349 ± 282 | 47 | 320 ± 217 | 45 | 313 ± 449 |

| hydroperoxide | Week 52 | 69 | 294 ± 236 | 36 | 261 ± 224 | 37 | 264 ± 226 |

| (nmol/L) | %Change | 60 | −0.9 ± 48.1 | 31 | −11.1 ± 34.1 | 33 | 9.0 ± 49.9 |

| p = 0.294 | p = 0.352 | ||||||

| hsCRP (mg/dL) | Baselinea | 105 | 0.16 ± 0.21 | 52 | 0.15 ± 0.20 | 50 | 0.19 ± 0.23 |

| Week 52 | 69 | 0.13 ± 0.18 | 36 | 0.09 ± 0.13 | 38 | 0.19 ± 0.22 | |

| %Change | 69 | 30.3 ± 264.0 | 36 | −3.0 ± 78.4 | 38 | 123.9 ± 406.3 | |

| p = 0.462 | p = 0.152 | ||||||

Mean values at baseline were based on the average of multiple measurements during the pretreatment period (week −4 to week 0)

p values represent the comparison of the percent changes between the combination group and the specified group by two-sample t-test (two-sided).

A single measurement at week 0

p < 0.05 for the within-group comparison by one sample t-test.

Apo, apolipoprotein; RemL-C, remnant-like lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hsCRP high-sensitivity assay for C-reactive protein

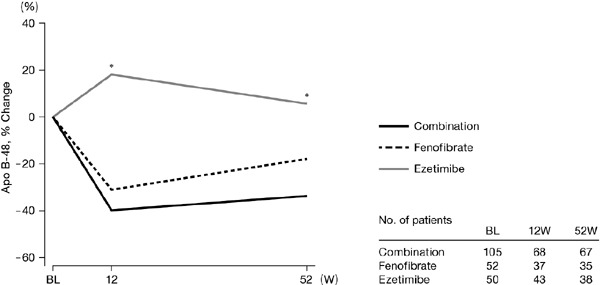

Concentrations of apo B-48 improved significantly more in the combination group than in the ezetimibe group (p < 0.001). Changes in apo B-48 were nearly the same as those in the combination and fenofibrate groups, which decreased slightly after week 12 (−39.8% ± 42.4% in the combination group and −31.0% ± 95.5% in the fenofibrate group). At week 52, changes in apo B-48 were −33.7% ± 56.4% in the combination group and −17.9% ± 98.9% in the fenofibrate group. The apo B-48 values in the ezetimibe group increased until week 12 (18.1% ± 90.4%) and then tended to decrease, returning to near-baseline value by week 52 (5.7% ± 60.4%) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Time course of change in apo B-48 by the study group

The mean value at baseline was defined as the mean of values of week 0.

*p < 0.05 (vs. Combination for percent change from baseline), two-sided for between-group comparison by two-sample t-test.

Apo, apolipoprotein; BL, baseline

Safety

There were no significant differences in percent-ages of categorical variables for main abnormal laboratory findings among the three groups, except that instances of red blood cell count below the lower limit of the standard reference range were significantly fewer in the ezetimibe group than in the fenofibrate group (p = 0.011) (Table 4). The final instances of hemoglobin below the lower limit of the standard reference range at the last visit tended to be fewer in the ezetimibe group than in the fenofibrate group (p = 0.067). Instances of uric acid exceeding the upper limit of the reference range at the last visit tended to be fewer in the combination group (p = 0.05) or in fenofibrate group (p = 0.053) than in the ezetimibe group. There were no patients who had AST (GOT) or ALT (GPT) exceeding the upper limit of the standard reference range at week 0 or the last visit.

Table 4. Proportions of patients with abnormal laboratory values by study group.

| Laboratory test | Definition of abnormal value | Combination % (n) |

Fenofibrate % (n) |

Ezetimibe % (n) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red blood cell count | Lower than the minimum of the standard range | Week 0 Last visit |

7.4 (7/94) 14.3 (14/98) |

7.7 (3/39) 26.7 (12/45) |

5.1 (2/39) 6.4 (3/47) |

| Hemoglobin | Lower than the minimum of the standard range§ | Week 0 Last visit |

8.4 (8/95) 14.3 (14/98) |

2.5 (1/40) 20.0 (9/45) |

5.1 (2/39) 6.4 (3/47) |

| Serum CPK | Higher than 2.5 times the maximum of the standard range | Week 0 Last visit |

1.0 (1/96) 0.0 (0/97) |

0.0 (0/41) 0.0 (0/45) |

0.0 (0/42) 0.0 (0/45) |

| Serum uric acid | Higher than the maximum of the standard range | Week 0 Last visit |

19.0 (19/100) 11.0 (11/100) |

25.0 (11/44) 8.3 (4/48) |

23.3 (10/43) 25.0 (12/48) |

| Serum creatinine | Higher than 1.5 times the maximum of the standard range | Week 0 Last visit |

0.0 (0/100) 1.0 (1/100) |

0.0 (0/44) 0.0 (0/48) |

0.0 (0/43) 4.2 (2/48) |

Values in parentheses are number of patients with abnormal value as denominator and total number of patients at the specified time as numerator.

The values for the last visit were based on the most recent visit during the treatment period (weeks 4, 8, 12, 24 or 52 or at the time of discontinuation).

In this study, abnormal hemoglobin findings were defined as “2 g/dL above the upper limit of the reference range,” and 0% of patients in any of the three groups met that definition either at week 0 or at the last visit. However, a number of patients showed hemoglobin levels lower than the standard reference range. Those findings have been included here for reference.

CPK, creatine phosphokinase

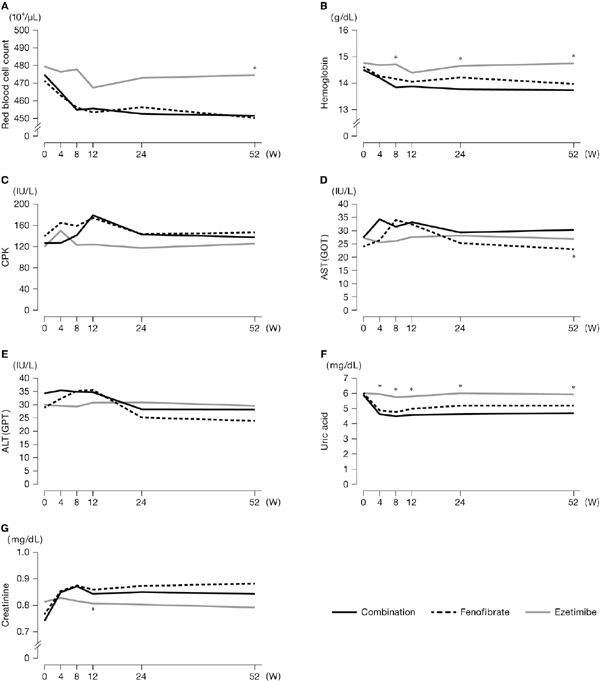

A comparison over time of actual values for laboratory tests showed that, overall, changes over time were similar between the combination and fenofibrate groups (Fig. 5, see Supplementary Table 2). Throughout the duration of the study, values for red blood cell count, hemoglobin, and uric acid were lower in the combination and fenofibrate groups than in the ezetimibe group. Creatinine increased in the combination and fenofibrate groups during the early treatment period, after which the increased level was maintained until week 52. No major changes were noted in the ezetimibe group. There were almost no changes in creatine phosphokinase (CPK), AST, or ALT among the three groups.

Fig. 5.

Time course of laboratory values

*p < 0.05 (vs. Combination value for the same week), two-sided for between-group comparison by Wilcoxon test.

CPK, creatine phosphokinase; AST (GOT), aspartate aminotransferase; ALT (GPT), alanine aminotransferase

Supplementary Table 2. Time course of laboratory values.

| Variable | Group | Weeks |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 24 | 52 | ||

| Red blood cell count, 104/µL | Combination | 475 ± 49 (94) | 465 ± 50* (73) | 455 ± 54* (61) | 456 ± 56* (65) | 453 ± 50* (69) | 452 ± 55* (68) |

| Fenofibrate | 471 ± 42 (39) | 463 ± 45* (37) | 456 ± 42* (35) | 453 ± 48* (34) | 456 ± 42* (35) | 450 ± 45* (34) | |

| Ezetimibe | 479 ± 49 (39) | 476 ± 49 (36) | 478 ± 49 (33) | 467 ± 46 (36) | 473 ± 45 (37) | 475 ± 43*§ (36) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | Combination | 14.5 ± 1.5 (95) | 14.2 ± 1.5* (74) | 13.8 ± 1.6* (62) | 13.9 ± 1.7* (66) | 13.8 ± 1.4* (70) | 13.7 ± 1.7* (68) |

| Fenofibrate | 14.6 ± 1.3 (40) | 14.3 ± 1.3* (38) | 14.2 ± 1.3* (36) | 14.1 ± 1.4* (35) | 14.2 ± 1.3 (36) | 14.0 ± 1.3* (34) | |

| Ezetimibe | 14.8 ± 1.7 (39) | 14.7 ± 1.7 (36) | 14.7 ± 1.6§ (33) | 14.4 ± 1.6 (36) | 14.7 ± 1.6§ (37) | 14.7 ± 1.4§ (36) | |

| CPK, IU/L | Combination | 127 ± 96 (96) | 127 ± 63 (78) | 142 ± 95* (65) | 179 ± 189* (69) | 143 ± 96* (70) | 138 ± 86* (70) |

| Fenofibrate | 140 ± 94 (41) | 165 ± 186 (40) | 159 ± 125 (37) | 174 ± 145 (34) | 143 ± 105 (34) | 147 ± 88 (33) | |

| Ezetimibe | 120 ± 54 (42) | 150 ± 152 (39) | 123 ± 48 (35) | 124 ± 56 (39) | 117 ± 47 (39) | 126 ± 45 (33) | |

| AST (GOT), IU/L | Combination | 27 ± 12 (100) | 34 ± 38 (83) | 32 ± 16 (69) | 33 ± 18* (70) | 29 ± 16 (72) | 30 ± 18 (70) |

| Fenofibrate | 24 ± 10 (44) | 26 ± 12* (42) | 34 ± 32* (38) | 32 ± 21* (36) | 25 ± 10 (37) | 23 ± 7§ (35) | |

| Ezetimibe | 27 ± 12 (44) | 26 ± 9 (40) | 26 ± 11 (36) | 28 ± 12 (39) | 28 ± 13 (39) | 27 ± 9 (35) | |

| ALT (GPT), IU/L | Combination | 34 ± 23 (100) | 35 ± 30 (83) | 35 ± 24 (69) | 35 ± 25 (70) | 28 ± 17* (72) | 28 ± 23* (70) |

| Fenofibrate | 29 ± 16 (44) | 32 ± 25 (42) | 35 ± 29 (38) | 36 ± 23 (36) | 25 ± 14 (37) | 24 ± 14* (35) | |

| Ezetimibe | 30 ± 18 (44) | 30 ± 18 (40) | 29 ± 22 (36) | 31 ± 18 (39) | 31 ± 18 (39) | 30 ± 13 (34) | |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | Combination | 5.9 ± 1.5 (100) | 4.6 ± 1.2* (80) | 4.5 ± 1.2* (66) | 4.6 ± 1.2* (70) | 4.6 ± 1.3* (72) | 4.7 ± 1.3* (70) |

| Fenofibrate | 6.0 ± 1.4 (44) | 4.9 ± 1.5* (42) | 4.8 ± 1.2* (38) | 5.0 ± 1.6* (36) | 5.2 ± 1.6* (37) | 5.2 ± 1.5* (35) | |

| Ezetimibe | 6.0 ± 1.4 (43) | 6.0 ± 1.4§ (40) | 5.8 ± 1.4§ (36) | 5.8 ± 1.5*§ (39) | 6.0 ± 1.3§ (39) | 5.9 ± 1.5§ (35) | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | Combination | 0.74 ± 0.16 (100) | 0.85 ± 0.18* (80) | 0.87 ± 0.23* (66) | 0.84 ± 0.18* (70) | 0.85 ± 0.29* (72) | 0.84 ± 0.21* (70) |

| Fenofibrate | 0.77 ± 0.20 (44) | 0.85 ± 0.20* (42) | 0.88 ± 0.21* (38) | 0.86 ± 0.20* (36) | 0.87 ± 0.16* (37) | 0.88 ± 0.21* (35) | |

| Ezetimibe | 0.81 ± 0.22 (43) | 0.83 ± 0.24 (40) | 0.82 ± 0.25 (36) | 0.81 ± 0.27§ (39) | 0.80 ± 0.21 (39) | 0.79 ± 0.23 (35) | |

Values are means ± SD and numbers of patients (in parentheses)

p < 0.05 (vs Baseline), one-sample Wilcoxon test;

p < 0.05 (vs Combination value for the same week), two-sided for between-group comparison by Wilcoxon test.

CPK, creatine phosphokinase; AST (GOT), aspartate aminotransferase; ALT (GPT), alanine aminotransferase

The overall incidence of adverse events was 14.0% (15 patients) in the combination group, 11.5% (6 patients) in the fenofibrate group, and 2.0% (1 patient) in the ezetimibe group (Table 5). The incidence in the combination group did not differ markedly from that in the fenofibrate group. The most frequently occurring adverse events were considered to be benign. In addition to the adverse events in Table 5, there was 1 event each of right lower back pain, reflux esophagitis, acute upper respiratory inflammation, lumber vertebral herniated disk, itching of hands and body, finger proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint pain, pain in both knees, back pain, general malaise, ureteral stone, and phlegm in the combination group and of cough asthma, cold, acute bronchitis, and nephropathy in the fenofibrate group. The CRE-increase shown in Table 5 was based on a physicians' report and occurred in a different patient than the one reported with nephropathy. In the patient with CRE-increase, creatinine values trended from 0.57 mg/dL at week 0 to 0.73 mg/dL at week 4, 0.71 mg/dL at week 8, 0.74 mg/dL at week 12, 0.81 mg/dL at week 24, and 0.66 mg/dL at week 52. Based on these changes in time course, the event was not considered clinically problematic. The overall incidence of adverse events was significantly lower in the ezetimibe group than in the combination group (p = 0.022), primarily because of a low incidence of increased AST and ALT, liver function abnormalities, and abdominal pain in the ezetimibe group. One instance of fatal arrhythmia occurred in the fenofibrate group. However, the primary doctor concluded that there was no causal relationship between the arrhythmia and fenofibrate administration.

Table 5. Physician's report of adverse events during the treatment period.

| Reported adverse episode | Combination n = 107 |

Fenofibrate n = 52 |

Ezetimibe n = 51 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | n of episodes | % (n) | n of episodes | % (n) | n of episodes | |

| Total | 14.0% (15) | 23 | 11.5% (6) | 16 | 2.0%* (1) | 1 |

| AST-increase | 2.8% (3) | 3 | 3.8% (2) | 2 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| ALT-increase | 1.9% (2) | 2 | 3.8% (2) | 2 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Stomachache | 2.8% (3) | 3 | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Liver dysfunction | 1.9% (2) | 2 | 1.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Muscle contraction | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 3.8% (2) | 2 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Creatinine level increase | 0.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Liver function test values increase | 0.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Liver function increase (liver function abnormalities) | 0.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Gallstone | 0.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| CRE-increase | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 1.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Edema | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 1.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Liver disorder | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 1.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Nephropathy | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 1.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Precordial pain | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 1.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Lethal arrhythmia | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 1.9% (1) | 1 | 0.0% (0) | 0 |

| Hyperuricemia | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 0.0% (0) | 0 | 2.0% (1) | 1 |

p < 0.05 (vs Combination), between-group comparison by Fisher's exact test.

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase

Gallstones detected by abdominal ultrasound had developed by week 52 in only 2 patients (2.8%) in the combination therapy group; one of those events was reported by the physician as having developed during the study.

Other Exploratory Endpoints

The number of patients with familial combined hyperlipidemia was too small to evaluate. This diagnosis was based on the judgement of the physician in charge of each patient; thus, it is possible that some cases were missed. Changes in serum lipid subclass did not differ significantly between baseline and week 52.

Discussion

We compared combination therapy with fenofibrate and ezetimibe to each drug alone in patients with combined hyperlipidemia. Combination therapy was more effective than either drug alone and had a safety profile similar to that for fenofibrate monotherapy.

Fenofibrate activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) within the hepatocyte nucleus. This activation affects the development of various proteins related to lipid metabolism and improves lipid metabolism4–6). In contrast, ezetimibe inhibits the transport of cholesterol by Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 (NPC1L1), a cholesterol transporter present on the small intestine brush border membrane. This inhibition reduces the absorption of biliary and dietary cholesterol from the small intestine16–18).

Because fenofibrate and ezetimibe have different mechanisms of action, their combined use is expected to yield more favorable lipid profile than the use of either fenofibrate or ezetimibe alone. The combination is of particular interest because it does not involve the use of statins, which have been linked to an increased risk of rhabdomyolysis.

Fenofibrate increases cholesterol excretion through the bile and has been associated with increased gallstone formation. One case with gallstone was observed; however, it was not concluded that the fenofibrate–ezetimibe combination increased the risk of gall stone formation. Little is known about how the use of this combined therapy may affect other adverse reactions that are observed with either fenofibrate or ezetimibe in monotherapy.

Several studies in Europe and the United States have evaluated the effectiveness and safety of combined therapy with fenofibrate and ezetimibe19, 20). Neither of these studies focused on Japanese patients, and the use of a single-arm design made it difficult to obtain sufficient information for the assessment of safety and efficacy of the fenofibrate–ezetimibe combination. Moreover, although combination therapy with bezafibrate and ezetimibe was investigated in a prospective observational study in Japan21), that study also used a single-arm design, which prevented the assessment of safety and efficacy of combination therapy in comparison with that of fibrate and ezetimibe alone.

In addition, the safety of fenofibrate–ezetimibe combination therapy has not yet been investigated in Japanese patients, and the package inserts for these two drugs contain some limitations on combined use. Clearly, there is a gap in our data on the efficacy and safety of the combination of fenofibrate and ezetimibe in Japan. This clinical study was conducted to help fill that gap.

Efficacy

Lipid Variables

In 52 weeks of treatment, LDL-C concentrations decreased more in the combination group than in the fenofibrate and ezetimibe groups. In the combination group, TG decreased and HDL-C increased at about the same rates as that with fenofibrate alone and significantly more than that with ezetimibe alone. These results were consistent with those reported earlier19, 20).

Changes over time showed that TG initially decreased in the fenofibrate monotherapy group, with the greatest percent reduction at week 12, and then gradually increased. This increase did not occur in the combination group, where the maximum percent reduction was sustained through week 52. The reasons for this increase remain poorly understood at this point, but the phenomenon definitely occurs in clinical settings. Because TG is easily influenced by the effects of meals, among other factors, those phenomena may be related to the results from long-term follow-up observation (attenuation from anticipated values in the fenofibrate group). Although ezetimibe alone has no pronounced TG-reducing effect, its mechanism of actions suggests that it inhibits TG synthesis in the small intestine22), which may explain the relatively stable results that were obtained with combination therapy. Consideration of such effects is warranted.

Lipid-related Characteristics

Between treatment baseline and week 52, concentrations of apo A-I, A-II, B, B-48, C-II, C-III, E, and RemL-C changed significantly in the combination group; concentrations of apo A-I, A-II, B, C-II, C-III, and E changed significantly in the fenofibrate group; and concentrations of apo B, and E changed significantly in the ezetimibe group. The combination group differed significantly from the fenofibrate group in concentrations of apo B, and RemL-C, and from the ezetimibe group in concentrations of apo A-I, A-II, B, B-48, C-II, C-III, E, and RemL-C. All lipid variables and almost all lipid-related variables improved in the combination group. The fenofibrate group improved primarily in TG-related variables, and the ezetimibe group improved primarily in LDL-C-related variables.

Changes over time in apo B-48, a TG-related variable, were similar to the overall trends in TG. The importance of apo B-48 in the risk of cardiovascular events is unknown, but elevated apo B-48 has recently been reported to be associated with reduced kidney function and kidney disorders23). Further study is anticipated.

LDL particle size increased significantly in the combination and fenofibrate groups, and HDL particle size decreased significantly in both the groups. No such changes were noted in the ezetimibe group. These findings suggest that particle size improved as TG was reduced.

We found no significant changes in phospholipid hydroperoxide from baseline to after administration.

Other Characteristics

HsCRP, which may reflect effects such as the inhibition of inflammation due to lipid reduction, did not change between baseline and week 52. No changes in BMI were noted in any of the groups throughout the duration of the study.

Safety

Adverse Events

The incidence of adverse events was significantly higher in the combination group than in the ezetimibe group. However, no individual adverse events occurred especially frequently, and there were no particular concerns about increased risk from combination therapy. Increases in AST and ALT were noted in the combination and fenofibrate groups, as were instances of abnormal liver function. However, the two groups did not differ significantly, and combination therapy was not considered to be associated with increased risk.

We found no gallstones in patients treated with fenofibrate or ezetimibe alone, but they were found in two patients in the combination group. For combination therapy in ordinary clinical practice, caution is warranted regarding potential gallstone development.

Abnormal Laboratory Results

Liver function-related adverse events were noted in the combination and fenofibrate groups. However, all test values were within the standard reference ranges in all patients with adverse events. These events were considered to be comparatively mild.

Creatinine concentrations increased significantly from baseline in the combination and fenofibrate groups. However, the two groups did not differ significantly in this study, which suggests that the risk of combination therapy should be no greater than that of fenofibrate monotherapy in actual clinical practice.

Uric acid concentrations were significantly lower at week 52 than at baseline in the combination and fenofibrate groups, but were unchanged in the ezetimibe group. Fenofibrate reduces uric acid concentrations; the mechanism of action appears to be the inhibition of URAT1, a transporter that is present in the proximal renal tubules and that mediates uric acid resorption24). In this study, the combination and fenofibrate groups showed similarly reduced uric acid concentrations, suggesting that the action of fenofibrate was similar in both the groups.

Hemoglobin concentrations decreased significantly during the study, in both the combination and fenofibrate groups. Decreased hemoglobin concentration, although rare, is a known adverse reaction to fenofibrate. The cause is unknown. In this study, the incidence of decreased hemoglobin did not differ between the combination and fenofibrate groups, and combination therapy was not associated with an increased risk of safety problems.

Limitations of the Study

The study was not a placebo-controlled comparative study; hence, caution is required in interpreting the study data. Though measurements were performed at a central laboratory for serum lipids, lipid-related variables, and HbA1c to avoid bias in assessment, other laboratory tests were conducted under various conditions at the individual study centers, which may have reduced reliability. This study was limited to patients with combined hyperlipidemia. It is desirable to investigate the safety and efficacy of coadministration of fenofibrate and ezetimibe in patients with lipid disorders who come from a wide variety of backgrounds. Because fenofibrate and ezetimibe have different mechanisms of action, a wide range of effects can be expected from combination therapy. Further detailed study of the effects of combination therapy on physiological functions other than lipid variables may provide important new findings that will be useful in a clinical setting.

Conclusions

Our results support the conclusions that combination therapy with fenofibrate and ezetimibe is safe for long-term use in patients with combined hyperlipidemia and that it substantially reduced LDL-C and TG concentrations in Japanese patients.

Acknowledgements

The research funds for the EFECTL study were provided to the Comprehensive Support Project for Clinical Research of Lifestyle-Related Disease of the Public Health Research Foundation, the Secretariat of the study, by Aska Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., the manufacturer of fenofibrate. EDIT, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) provided medical writing and editing of the manuscript for submission, which was funded by the Comprehensive Support Project for Clinical Research of Lifestyle-Related Disease of the Public Health Research Foundation. The authors have final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Notes of Grant Support

The funder, the Comprehensive Support Project for Clinical Research of Lifestyle-Related Disease of the Public Health Research Foundation, worked on overall management of the study as the Secretariat. Neither the funder nor the sponsor, Aska Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. had any role in study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Special Thanks to

Our sincere thanks to everyone who was involved in this study: the physicians, staff, support personnel, and especially the participating patients.

Clinical Trial Registration Number: UMIN000001224

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure

Shinichi Oikawa reports research funding from the Kidney Foundation, Japan, Astellas Pharma Inc. Shizuya Yamashita reports honoraria from MSD K.K., Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., Kowa Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co., Ltd., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Medical Review Co., Ltd. and Skylight Biotech, Inc., and clinical research funding from Nippon Boehringer-Ingelheim Co., Ltd., Kyowa Medex Co., Ltd. and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and scholarship grants from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co., Ltd., Kowa Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Nippon Boehringer-Ingelheim Co., Ltd., AstraZeneca K.K., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., MSD K.K., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., and courses endowed from Izumisano City, Kaizuka City. Jun Sasaki reports research funding from Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., and scholarship grants from Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited. Noriaki Nakaya and Suminori Kono have no conflict interest.

Appendix

The following persons participated in this study.

Principal Investigators: Shinichi Oikawa

Steering Committee: Shinichi Oikawa, Shizuya Yamashita, Noriaki Nakaya, Jun Sasaki, Suminori Kono, Teruo Miyazawa, Kiyotaka Nakagawa

Data Center: Medical TOUKEI Corporation (Tokyo, Japan)

Investigators: Masumi Ai (Tanaka Clinic), Toshihide Arai (Arai Clinic), Takanori Boku (Saiseikai Suita Hospital), Ryuichirou Imawatari (Imawatari Clinic), Masafumi Kakei (Saitama Medical Center Jichi Medical University), Fumitaka Kamada (Kamada Clinic), Masahiro Kamegai (Chiyoda Clinic), Mitsuhiko Kawaguchi (Kawaguchi Medical Clinic), Tatsuya Kobayashi (Kosei Clinic), Hidetoshi Kotake (Tsurugaya Clinic), Atsushi Kuno (Kuno Clinic), Kosuke Mabuchi (Kanda Clinic), Yasushi Mitsugi (Jyuzen Hospital), Hiroshi Miyata (Sugimoto Clinic), Yoshifumi Mizuno (Mizuno Clinic), Daiki Morishita (Shinmura Hospital), Satoshi Murao (Takamatsu Hospital), Osamu Nakano (Nakano Clinic), Noriaki Nakaya (Nakaya Clinic), Shinichi Oikawa (Nippon Medical School Hospital), Takeshi Okuda (Okuda Clinic), Atsuyuki Ohno (Kasai Shoikai Hospital), Nobuo Ono (Ono Clinic), Masayuki Ootaki (Tenjinmae Clinic), Ichiro Sakuma (Caress Sapporo Hokko Memorial Hospital), Yasunori Sawayama (Japanese Red Cross Fukuoka Hospital), Tetsuya Tagami (National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center), Takao Uozumi (Wagougaoka Clinic), Hiroaki Yagyu (Jichi Medical University Hospital), Haruaki Yamamoto (Yamamoto Clinic), Tomohiko Yoshida (Yoshida Clinic)

References

- 1). Fujihara K, Sugawara A, Heianza Y, Sairenchi T, Irie F, Iso H, Doi M, Shimano H, Watanabe H, Sone H, Ota H: Utility of the triglyceride level for predicting incident diabetes mellitus according to the fasting status and body mass index category: The Ibaraki Prefectural Health Study. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2014; 21: 1152-1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Japan Atherosclerosis Society: Hyperlipidemia Treatment Guide 2013, Japan Atherosclerosis Society, Tokyo, Japan, 2013. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 3). Jacobson TA, Zimmerman FH: Fibrates in combination with statins in the management of dyslipidemia. J Clin Hypertens, 2006; 8: 35-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Schoonjans K, Peinado-Onsurbe J, Lefebvre AM, Heyman RA, Briggs M, Deeb S, Staels B, Auwerx J: PPARα and Par activators direct a distinct tissue-specific transcriptional response via a PPRE in the lipoprotein lipase gene. EMBO J, 1996; 15: 5336-5348 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Staels B, Vu-Dac N, Kosykh VA, Saladin R, Fruchart JC, Dallongeville J, Auwrex J: Fibrates downregulate apolipoprotein C-III expression independent of induction of peroxisomal acyl coenzyme A oxidase. A potential mechanism for the hypolipidemic action of fibrates. J Clin Invest, 1995; 95: 705-712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Schoonjans K, Staels B, Auwerx J: Role of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) in mediating the effects of fibrates and fatty acids on gene expression. J Lipid Res, 1996; 37: 907-925 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study Investigators: Effect of fenofibrate on progression of coronary-artery disease in type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study, a randomised study. Lancet, 2001; 357: 905-910 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Keech A, Simes RJ, Barter P, Best J, Scott R, Taskinen MR, Forder P, Pillai A, Davis T, Glasziou P, Drury P, Kesäniemi YA, Sullivan D, Hunt D, Colman P, d'Emden M, Whiting M, Ehnholm C, Laakso M, FIELD study investigators : Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2005; 366: 1849-1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, Darius H, Lewis BS, Ophuis TO, Jukema JW, De Ferrari GM, Ruzyllo W, De Lucca P, Im K, Bohula EA, Reist C, Wiviott SD, Tershakovec AM, Musliner TA, Braunwald E, Califf RM, IMPROVE-IT Investigators : Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med, 2015; 372: 2387-2397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem, 1972; 18: 499-502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Japan Atherosclerosis Society: Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Guidelines for Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases 2007, Japan Atherosclerosis Society, Tokyo, Japan, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Goto Y, Saito Y, Itakura H, Hata Y, Nakaya N, Mabuchi H, Nakai T, Hidaka H, Kita T, Matsuzawa Y, Tsushima M: Clinical efficacy of GRS-001 (fenofibrate) in longterm treatment on hyperlipidemia. Geriat Med, 1995; 33: 909-938 (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 13). Yamada N, Saito Y, Nakaya N, Teramoto T, Oikawa S, Yamashita S, Tsushima M, Yamamoto A: Clinical evaluation of ezetimibe in long-term treatment in patients with hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Therap Med, 2007; 23: 523-554 (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 14). Mabuchi H, Goto Y, Nakai T, Hidaka H, Kita T, Tsushima M, Matsuzawa Y: Study on the usefulness of GRS-001 in hyperlipidemia. Double-blind group comparison trial using clinofibrate tablet as the reference drug. Clin Eval, 1995; 23: 247-305 (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 15). Hochberg Y: A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika, 1988; 75: 800-802 [Google Scholar]

- 16). Altmann SW, Davis HR, Jr, Zhu LJ, Yao X, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Iyer SP, Maguire M, Golovko A, Zeng M, Wang L, Murgolo N, Graziano MP: Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 protein is critical for intestinal cholesterol absorption. Science, 2004; 303: 1201-1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Davis HR, Jr, Zhu LJ, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Maguire M, Liu J, Yao X, Iyer SP, Lam MH, Lund EG, Detmers PA, Graziano MP, Altmann SW: Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 (NPC1L1) is the intestinal phytosterol and cholesterol transporter and a key modulator of whole-body cholesterol homeostasis. J Biol Chem, 2004; 279: 33586-33592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Garcia-Calvo M, Lisnock J, Bull HG, Hawes BE, Burnett DA, Braun MP, Crona JH, Davis HR, Jr, Dean DC, Detmers PA, Graziano MP, Hughes M, Macintyre DE, Ogawa A, O'neill KA, Iyer SP, Shevell DE, Smith MM, Tang YS, Makarewicz AM, Ujjainwalla F, Altmann SW, Chapman KT, Thornberry NA: The target of ezetimibe is Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005; 102: 8132-8137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Farnier M, Freeman MW, Macdonell G, Perevozskaya I, Davies MJ, Mitchel YB, Gumbiner B, Ezetimibe Study Group : Efficacy and safety of the coadministration of ezetimibe with fenofibrate in patients with mixed hyperlipidaemia. Eur Heart J, 2005; 26: 897-905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Mckenney JM, Farnier M, Lo KW, Bays HE, Perevozkaya I, Carlson G, Davies MJ, Mitchel YB, Gumbiner B: Safety and efficacy of long-term co-administration of fenofibrate and ezetimibe in patients with mixed hyperlipidemia. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2006; 47: 1584-1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Teramoto T, Abe K, Taneyama T: Safety and efficacy of long-term combination therapy with bezafibrate and ezetimibe in patients with dyslipidemia in the prospective, observational J-COMPATIBLE study. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2013; 12: 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Sandoval JC, Nakagawa-Toyama Y, Masuda D, Tochino Y, Nakaoka H, Kawase R, Yuasa-Kawase M, Nakatani K, Inagaki M, Tsubakio-Yamamoto K, Ohama T, Matsuyama A, Nishida M, Ishigami M, Komuro I, Yamashita S: Molecular mechanisms of ezetimibe-induced attenuation of postprandial hypertriglyceridemia. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2010; 17: 914-924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Okubo M, Hanada H, Matsui M, Hidaka Y, Masuda D, Sakata Y, Yamashita S: Serum apolipoprotein B-48 concentration is associated with a reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate and increased proteinuria. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2014; 21: 974-982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Uetake D, Ohno I, Ichida K, Yamaguchi Y, Saikawa H, Endou H, Hosoya T: Effect of fenofibrate on uric acid metabolism and urate transporter 1. Intern Med, 2010; 49: 89-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]