Abstract

Objective To quantify the cost effectiveness of a government policy combining targeted industry agreements and public education to reduce sodium intake in 183 countries worldwide.

Design Global modeling study.

Setting 183 countries.

Population Full adult population in each country.

Intervention A “soft regulation” national policy that combines targeted industry agreements, government monitoring, and public education to reduce population sodium intake, modeled on the recent successful UK program. To account for heterogeneity in efficacy across countries, a range of scenarios were evaluated, including 10%, 30%, 0.5 g/day, and 1.5 g/day sodium reductions achieved over 10 years. We characterized global sodium intakes, blood pressure levels, effects of sodium on blood pressure and of blood pressure on cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease rates in 2010, each by age and sex, in 183 countries. Country specific costs of a sodium reduction policy were estimated using the World Health Organization Noncommunicable Disease Costing Tool. Country specific impacts on mortality and disability adjusted life years (DALYs) were modeled using comparative risk assessment. We only evaluated program costs, without incorporating potential healthcare savings from prevented events, to provide conservative estimates of cost effectiveness

Main outcome measure Cost effectiveness ratio, evaluated as purchasing power parity adjusted international dollars (equivalent to the country specific purchasing power of US$) per DALY saved over 10 years.

Results Worldwide, a 10% reduction in sodium consumption over 10 years within each country was projected to avert approximately 5.8 million DALYs/year related to cardiovascular diseases, at a population weighted mean cost of I$1.13 per capita over the 10 year intervention. The population weighted mean cost effectiveness ratio was approximately I$204/DALY. Across nine world regions, estimated cost effectiveness of sodium reduction was best in South Asia (I$116/DALY); across the world’s 30 most populous countries, best in Uzbekistan (I$26.08/DALY) and Myanmar (I$33.30/DALY). Cost effectiveness was lowest in Australia/New Zealand (I$880/DALY, or 0.02×gross domestic product (GDP) per capita), although still substantially better than standard thresholds for cost effective (<3.0×GDP per capita) or highly cost effective (<1.0×GDP per capita) interventions. Most (96.0%) of the world’s adult population lived in countries in which this intervention had a cost effectiveness ratio <0.1×GDP per capita, and 99.6% in countries with a cost effectiveness ratio <1.0×GDP per capita.

Conclusion A government “soft regulation” strategy combining targeted industry agreements and public education to reduce dietary sodium is projected to be highly cost effective worldwide, even without accounting for potential healthcare savings.

Introduction

Excessive sodium consumption is common and linked to cardiovascular burdens in most countries. Overall, 181 of 187 countries, representing 99.2% of the global adult population, have mean sodium intakes exceeding the World Health Organization recommended maximum of 2 g/day.1 Based on this threshold, an estimated 1 648 000 annual deaths from cardiovascular diseases worldwide were attributable to excess dietary sodium in 2010.2 Accordingly, the 2013 United Nations’ Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases has prioritized sodium reduction as one of nine key targets for all member nations in 2013-20.3

A potential barrier for implementation of this recommendation is cost. Many countries have limited resources for health interventions, requiring careful assessment of costs and cost effectiveness. Several countries now have national programs that include a specific aim of reducing population sodium intake; for instance, as of 2012, 29 European nations, consisting of all EU Member States as well as Norway and Switzerland, had salt reduction initiatives in place.4 Yet the cost effectiveness of such efforts globally is uncertain. While prior studies have estimated sodium reduction policies to be highly cost effective, or even cost saving, in specific countries, the potential cost effectiveness of such strategies has been analyzed for only a handful of nations and regions, mostly focused on high income nations, and in ways that are not generally comparable.5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

To address this key gap in knowledge, we assessed the cost effectiveness of sodium reduction strategies in 183 nations, based on the most up to date available data on age specific and sex specific sodium intakes, blood pressure levels, and cardiovascular disease burdens worldwide, the dose-response effects of sodium on blood pressure and of blood pressure on cardiovascular disease, and nation specific costs for each component of the intervention. Together, these allowed us to model and estimate, using comparable and consistent methods, the cost effectiveness of sodium reduction strategies for every country.

Methods

Sodium reduction intervention

We modeled the effects and costs of a 10 year government “soft regulation” policy to reduce population sodium consumption (see supplementary eTable 1 for details of the model assumptions). The intervention program was modeled on recent experience in the UK15 and included government supported industry agreements to reduce sodium in processed foods, government monitoring of industry compliance, and a public health campaign targeting consumer choices. In the UK, for example, this intervention was based on collaboration between national government offices focused on nutrition (Food Standards Agency) and health (ministers of public health), together with non-governmental advocacy organizations (Consensus Action on Salt & Health). The program applied sustained pressure on food manufacturers to pursue progressive reformulation, reinforced by food group specific targets, independent monitoring, and a sustained media campaign against excess salt intake. The program we modeled was thus more robust and costly than simple “voluntary reformulation.”

We assumed the intervention would scale up linearly over 10 years, with one 10th of the total sodium reduction in the first year, two 10ths in the second, and so on, reaching full efficacy in the final year. We recognized that alternative programs, such as mandatory regulation, would likely have larger effects, reduce sodium consumption more quickly, and at lower cost, but may be less politically feasible in many countries.

Intervention costs

Country specific resource needs and costs were derived using the WHO-CHOICE database,16 which includes detailed component specific estimates of inputs (ingredients) required for each intervention stage for each country’s government and the estimated unit price for each input in that country including for example costs of human resources, training, meetings, supplies, equipment, and mass media (see supplementary eMethods). To facilitate comparisons between countries, we converted all costs to international dollars (I$) (see supplementary eMethods), which account for each nation’s currency as well as purchasing power parity.17 One I$ in any given country can be interpreted as the funds needed to purchase the same amounts of goods or services in that country as one US$ would purchase in the US. For countries with lower incomes than the US, conversion of our findings from I$ to US$ would substantially increase the apparent cost effectiveness (ie, the cost in US$ per disability adjusted life year (DALY) saved would be much lower). We summed costs by year to calculate the total cost of the 10 year intervention for each country, with 3% annual discounting.

We modeled only governmental intervention costs, for several reasons. First, this cost is most relevant to budget constrained governments, since the program cost must be borne directly and immediately. Second, net industry sector costs for product reformulation in each country would be difficult to determine because once the relevant reformulation has been undertaken in any single country, the knowledge of that reformulation can be extended with much less additional cost to other countries. For example, multinational companies transfer improved recipes and reformulation strategies across borders with no cost, as do food scientists moving between firms, and so on. Third, in contrast to recent US models,10 11 we did not include estimated healthcare savings or increased productivity from prevented cardiovascular disease events because such savings could, in theory, be partly offset by new downstream health events resulting from enhanced survival18 19 and because comparable healthcare and productivity costing data are available for a minority of countries globally. Because including such cost savings would be optimal according to many cost effectiveness guidelines, our results for overall cost effectiveness should be considered a conservative estimate.

Heterogeneity in intervention costs and effectiveness

Though the WHO costing framework already accounted for some sources of variation by country in terms of resources required and nation specific costs, we recognized that details of planning, development, and implementation might further vary from country to country beyond what is captured by the costing tool. We also recognized that achieved effectiveness would vary from country to country. Our base model assumed an average cost of this framework (already adjusted for in-country differences in resource use and costs, according to the WHO costing tool), and an average effectiveness. To understand the robustness of our findings to these assumptions, we tested widely varying costs—including variations in resource use and cost of between 0.25-fold and fivefold the base—and varying intervention effectiveness, including 10% and 30% proportional reductions and 0.5 g/day and 1.5 g/day absolute reductions in sodium intake over 10 years. Plausible intervention effectiveness was informed by experiences in the UK, which achieved a 14.7% (0.6 g/day) reduction in population sodium intake over 10 years,20 and Turkey, which reported a more rapid 16% (1.2 g/day) reduction over four years.21 Together, these findings provided a broad range of possible scenarios against which to evaluate the cost effectiveness of the intervention.

Intervention impact on DALYs

Using data on population demographics, sodium consumption, blood pressure levels, and rates of cardiovascular disease, each in 26 strata by age and sex within each country,2 we estimated the number of disability adjusted life years that would be averted by the intervention in each country for each year between 2011 and 2020. Risk reduction in each age-sex-country stratum was calculated from the effect of sodium reduction on systolic blood pressure, including variation in this effect by age, race, and hypertensive status; and the effect of blood pressure reduction on cardiovascular disease, including variation in this effect by age.2 The final comparative risk assessment model incorporated each of these sources of heterogeneity, as well as their uncertainty. Stratum specific effects, accounting for underlying demographics and baseline cardiovascular disease rates, were summed to derive national (or regional) effects (see supplementary eMethods for details on these inputs and their modeling).

While some prior observational studies suggest a J-shaped relation between sodium intake and cardiovascular disease,22 this could be explained by potential biases of sodium assessment in observational studies (see supplementary eMethods).23 In extended follow-up of sodium reduction trials that overcame many of these limitations, linear risk reductions were seen, including lower risk with intakes less than 2.3 g/day.24 We recognized that while the precise optimal level of sodium intake remains controversial, every major national and international organization that has reviewed all the evidence has concluded that high sodium intake increases cardiovascular disease risk and that lowering sodium intake reduces such risk, with optimal identified intakes ranging from less than 1.2 g/day to less than 2.4 g/day.2 We used an optimal intake of 2.0 g/day (WHO) for our main analysis. For any sodium reductions below this level, we modeled neither additional benefit nor risk, consistent with recent Institute of Medicine conclusions.25 In sensitivity analyses, we also evaluated lower (1.0 g/day) and higher (3.0 g/day) thresholds for optimal intake.

Our modeling further utilized known strengths of blood pressure as “an exemplar surrogate endpoint for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity.”26 Prospective cohort studies suggest log-linear associations between systolic blood pressure and cardiovascular disease events, down to around 110 mm Hg27; and randomized controlled trials indicate that benefits of blood pressure lowering interventions are largely proportional to the magnitude of blood pressure reduction, rather than the specific intervention, with similar proportional reductions in cardiovascular disease events down to pretreatment blood pressures of around 110 mm Hg.27 28 29 In our model, we assumed a log-linear dose-response between blood pressure and cardiovascular disease until a systolic blood pressure level of 115 mm Hg, below which we assumed no further lowering of risk. Given the relatively rapid reductions in cardiovascular disease events in randomized trials of blood pressure lowering therapies, and the prolonged period of our intervention (10 years), we did not model any lag and assumed concurrent gradual benefits in both blood pressure reduction and cardiovascular disease.

Cost effectiveness ratios

To calculate the cost effectiveness ratio for each country, we divided the total effect on DALYs by the total cost of the intervention over 10 years. We compared these cost effectiveness ratios to WHO benchmarks, which define a cost effectiveness ratio <3×gross domestic product (GDP) per capita as cost effective, and <1×GDP per capita as highly cost effective.30 We appreciated the potential limitations of these WHO benchmarks31 yet also their practicality for multinational studies such as this. To quantify statistical uncertainty, we used probabilistic sensitivity analyses based on 1000 Monte Carlo simulations to derive 95% uncertainty intervals, with varying inputs for sodium use, blood pressure levels, effects of sodium on blood pressure, and effects of blood pressure on cardiovascular disease (see supplementary eMethods).

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

Cost effectiveness of sodium reduction by national income level and region

Taking into account local prices, currencies, and purchasing power, the relative contributions of each intervention component to the total 10 year cost differed appreciably between countries (see supplementary eFigure 1). For instance, costs of supplies and equipment, meetings, and training were uniformly low (averaging I$0.01 per capita, I$0.01 per capita, and I$0.04 per capita, respectively), whereas costs of human resources and mass media were much higher and more variable across countries. Globally, average purchasing power parity adjusted costs for human resources (personnel salaries) were I$0.27 per capita, but with a ninefold range comparing high income (I$0.93) with low income (I$0.10) countries. Human resources were most costly in Australia/New Zealand (I$1.26 per capita), Western Europe (I$1.03), and Canada/US (I$0.82); and lowest in South Asia (I$0.06). Mass media costs were generally the most expensive component of the intervention: I$0.80 per capita globally, I$1.07 for high income nations, and I$0.44 for low income nations. They represented the most costly component of the intervention in every region except for Australia/New Zealand, Canada/US, and Western Europe, where human resources was the most costly component.

Globally, the estimated average cost effectiveness ratio of the 10 year intervention was approximately I$204 per DALY saved (95% uncertainty interval I$149 to I$322) (table 1). This did not include potential savings from lower healthcare costs or higher productivity owing to averted cardiovascular disease events, which would each further improve the estimated cost effectiveness. The estimated cost effectiveness ratio was lowest (best) in lower middle income (I$111, I$81 to I$175) and upper middle income countries (I$146, I$109 to I$223), higher in low income countries (I$215, I$139 to I$400), and highest in high income countries (I$465, I$341 to I$724). By region, the lowest cost effectiveness ratios were in South Asia and East/Southeast Asia (I$116 and I$123, respectively). In Central Asia/Eastern and Central Europe, high intervention efficacy partly offset its higher projected cost, generating the next best cost effectiveness ratio (I$211, I$157 to I$324).

Table 1.

Cost effectiveness by income and geographic region of a national government supported policy intervention to reduce sodium consumption by 10% over 10 years*

| Variables | Population characteristics | Costs/capita (I$) (10 year total) | Total DALYs averted per year (average) | 10 year intervention | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult population (millions) | Sodium (g/day) (95% UI) | SBP (mm Hg) (95% UI) | Intervention cost | GDP | All CVD (95% UI) | CHD† (95% UI) | Stroke (95% UI) | Other CVD (95% UI) | I$/DALY (95% UI) | ||||

| Total | Weighted average | Weighted average | Weighted average | Weighted average | Total | Total | Total | Total | Weighted average | ||||

| World‡ | 3818 | 4.0 (3.5 to 4.4) | 126 (121 to 132) | 1.13 | 13 529 | 5 781 193 (3 839 910 to 7 649 940) | 2 426 749 (1 592 687 to 3 251 879) | 2 318 402 (1 560 469 to 3 035 231) | 1 036 042 (688 446 to 1 368 222) | 204 (149 to 322) | |||

| High income§ | 755 | 4.0 (3.6 to 4.3) | 127 (122 to 133) | 2.07 | 38 818 | 783 883 (510 386 to 1 054 176) | 396 007 (259 797 to 534 578) | 222 376 (146 908 to 295 486) | 165 500 (107 651 to 221 276) | 465 (341 to 724) | |||

| Upper middle income | 1528 | 4.4 (4.0 to 4.8) | 127 (122 to 132) | 1.09 | 11 001 | 2 660 459 (1 763 649 to 3 486 628) | 1 003 729 (652 361 to 1 333 710) | 1 237 874 (838 534 to 1 617 955) | 418 856 (280 732 to 547 912) | 146 (109 to 223) | |||

| Lower middle income | 1212 | 3.7 (3.3 to 4.3) | 124 (119 to 130) | 0.74 | 4100 | 1 940 077 (1 267 576 to 2 587 018) | 902 273 (578 668 to 1 217 060) | 679 192 (451 077 to 905 715) | 358 612 (234 396 to 476 896) | 111 (81 to 175) | |||

| Low income | 323 | 3.1 (2.3 to 3.8) | 126 (118 to 135) | 0.62 | 1456 | 396 773 (269 537 to 527 676) | 124 739 (84 056 to 166 821) | 178 959 (121 972 to 236 400) | 93 075 (62 353 to 124 737) | 215 (139 to 400) | |||

| Australia and New Zealand | 17 | 3.4 (3.3 to 3.7) | 124 (117 to 131) | 2.63 | 40 181 | 11 254 (7 189 to 15 198) | 6 659 (4 217 to 9 081) | 2 495 (1 588 to 3 357) | 2 100 (1 333 to 2 876) | 880 (646 to 1382) | |||

| Canada and US | 226 | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) | 123 (118 to 127) | 1.67 | 48 940 | 238 357 (156 342 to 326 196) | 136 604 (88 092 to 189 180) | 48 032 (31 392 to 64 965) | 53 721 (34 784 to 72 166) | 350 (257 to 537) | |||

| Central Asia/Eastern and Central Europe | 273 | 4.3 (3.6 to 5.0) | 133 (126 to 140) | 2.71 | 14 833 | 944 059 (615 884 to 1 245 547) | 530 472 (347 931 to 707 931) | 307 475 (204 004 to 403 720) | 106 112 (69 804 to 140 615) | 211 (157 to 324) | |||

| East and Southeast Asia | 1354 | 4.6 (4.3 to 5.1) | 126 (121 to 130) | 0.83 | 10 777 | 2 139 880 (1 428 092 to 2 809 299) | 617 817 (405 227 to 826 603) | 1 176 978 (793 689 to 1 535 809) | 345 084 (230 836 to 449 547) | 123 (93 to 184) | |||

| Latin America and Caribbean | 316 | 3.5 (3.1 to 3.9) | 126 (120 to 133) | 0.93 | 12 505 | 325 607 (212 912 to 437 512) | 140 529 (90 822 to 191 668) | 110 632 (72 322 to 146 709) | 74 446 (48 485 to 99 236) | 236 (171 to 375) | |||

| North Africa and Middle East | 225 | 3.9 (3.3 to 4.7) | 125 (118 to 131) | 1.31 | 12 436 | 367 829 (235 762 to 498 060) | 171 883 (109 403 to 233 374) | 112 826 (72 727 to 152 981) | 83 120 (53 259 to 111 970) | 300 (215 to 490) | |||

| South Asia | 786 | 3.7 (3.4 to 4.1) | 123 (117 to 128) | 0.74 | 3551 | 1 136 614 (733 267 to 1 534 026) | 582 096 (364 382 to 791 879) | 331 062 (218 435 to 444 645) | 223 456 (143 221 to 299 264) | 116 (85 to 182) | |||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 320 | 2.5 (2.0 to 3.0) | 130 (123 to 137) | 0.83 | 2743 | 335 053 (202 998 to 468 036) | 95 140 (58 076 to 133 355) | 156 910 (95 447 to 218 782) | 83 003 (50 151 to 116 135) | 255 (166 to 473) | |||

| Western Europe | 301 | 3.8 (3.5 to 4.3) | 130 (124 to 136) | 1.98 | 35 676 | 282 541 (183 440 to 380 484) | 145 548 (94 348 to 196 380) | 71 992 (46 942 to 96 720) | 65 000 (41 894 to 87 414) | 477 (350 to 744) | |||

DALYs=disability adjusted life years; UI=uncertainty interval; SBP=systolic blood pressure; GDP=gross domestic product; CVD=cardiovascular disease; CHD=coronary heart disease.

*National program including: public health campaign targeting consumer knowledge and choices, government supported industry agreements to reduce sodium in processed foods to specific targets, and government monitoring of industry compliance. These results reflect the total effect over a 10 year policy intervention that includes planning (year 1), development (year 2), partial implementation (years 3-5), and full implementation (years 6-10). To enable comparisons between countries, all costs were evaluated in international dollars (I$), accounting for each nation’s currency and purchasing power parity. One I$ in any given country can be interpreted as the funds needed to purchase the same amounts of goods or services in that country as one US$ would purchase in the US. For countries with lower income than in the US, conversion of our findings from I$ to US$ would substantially increase the apparent cost effectiveness (ie, the cost in US$ per DALY saved would be much lower).

†Stroke includes ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic and other non-ischemic stroke; and other CVD includes aortic aneurysm, atrial fibrillation and flutter, cardiomyopathy and myocarditis, endocarditis, hypertensive heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, rheumatic heart disease, and other cardiovascular and circulatory diseases.

‡In 2010 globally, the total burden of CVD was 295 035 800 DALYs, of which CHD accounted for 129 819 900 DALYs, stroke 102 232 300 DALYs, and other CVD 62 983 600 DALYs. There were 14 669 000 total CVD deaths, of which 6 963 000 were CHD deaths, 5 798 000 stroke deaths, and 1 909 000 other CVD deaths. The numbers of deaths in each subtype may not exactly sum to the total CVD deaths owing to rounding.

§Income categorizations are based on the World Bank classification system (http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups).

Effectiveness, cost, and cost effectiveness by country

Across individual countries, the estimated intervention efficacy, in terms of DALYs averted per 1000 people, was highest in Kazakhstan (23.0, 95% uncertainty interval 15.6 to 29.8), Georgia (21.6, 14.3 to 28.3), Belarus (19.8, 12.8 to 26.9), Ukraine (19.0, 12.3 to 25.9), Mongolia (18.9, 12.1 to 25.0), and Russia (18.8, 12.2 to 25.5) (see supplementary eTable 3). The relative rankings of these nations should be considered in the context of the uncertainty in the estimates that preclude, for example, confirming statistically significant differences in efficacy between Kazakhstan and Russia. Yet, the range of estimated efficacy across the 183 nations was large—for example, compared with the countries above, much lower in Jamaica (1.9, 1.1 to 2.7), Qatar (1.4, 0.8 to 1.9), Rwanda (1.3, 0.6 to 2.3), and Kenya (0.4, 0.2 to 0.7).

Per capita, estimated 10 year intervention cost was lowest in Myanmar, Vietnam, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (each I$0.31), Thailand (I$0.33), Nepal (I$0.40), and Uzbekistan (I$0.41) (see supplementary eTable 3). A total of 68 countries had estimated 10 year intervention costs of less than I$1.00 per capita. For 84 countries, estimated costs were between I$1.00 and I$9.99, for 19 countries, between I$10 and I$29.99, and for 12, greater than I$30.

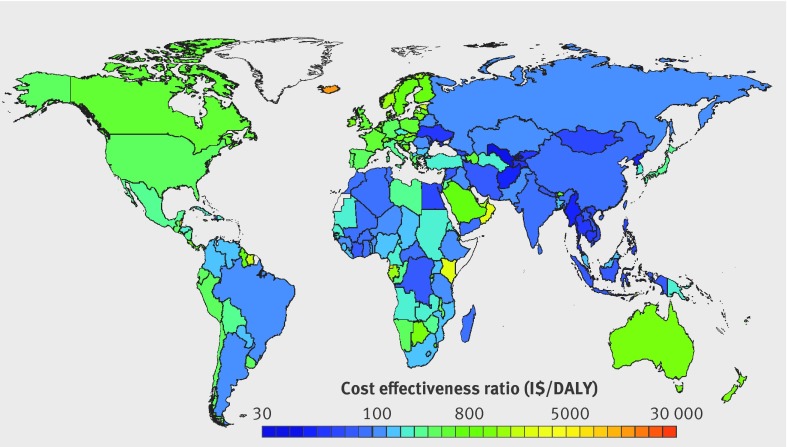

Estimated national cost effectiveness ratios were correspondingly variable (fig 1). Uzbekistan’s was lowest (best) at I$26.08/DALY (95% uncertainty interval 20.08 to 39.02), followed by Myanmar (I$33.30, 25.10 to 50.46). Twenty eight countries had estimated cost effectiveness ratios below I$100/DALY, and 112 more, below I$1000/DALY. Eleven nations, all small, had estimated cost effectiveness ratios between I$10 000 and I$30 000/DALY (see supplementary eTable 3).

Fig 1 Cost effectiveness (purchasing power adjusted I$/disability adjusted life year) by country of a national policy intervention to reduce sodium consumption by 10%

WHO benchmarks for cost effectiveness

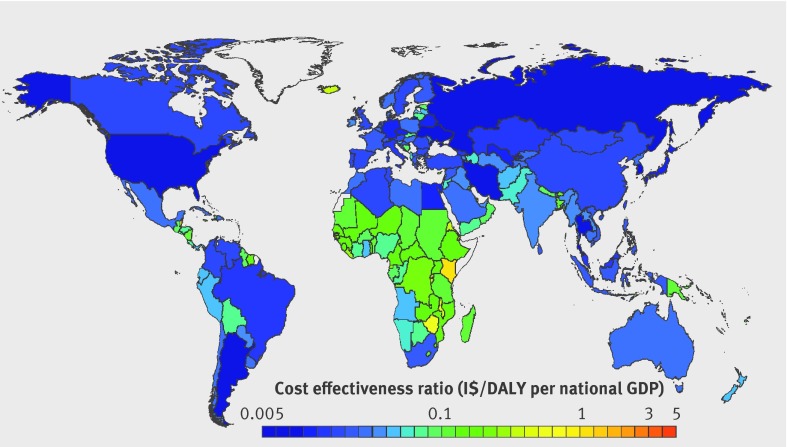

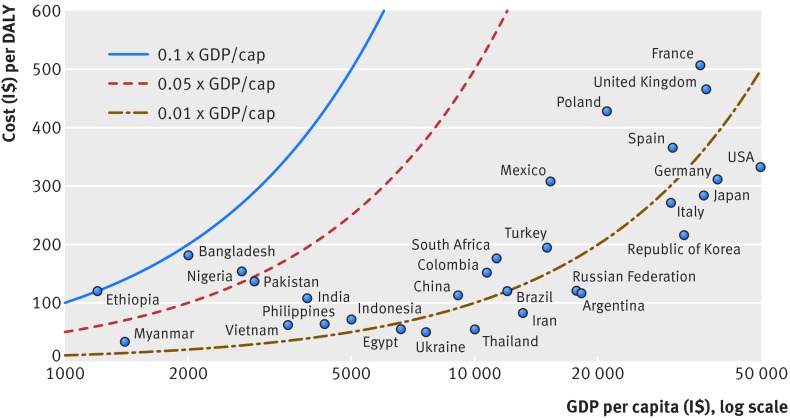

In comparison with WHO benchmarks (cost effectiveness ratio <3×GDP per capita is cost effective, <1×GDP per capita, highly cost effective),30 the 10 year sodium reduction intervention was estimated to be highly cost effective globally. Across all 183 countries, the estimated cost effectiveness ratio of this policy intervention was >3×GDP per capita in only one nation (Marshall Islands: 4.7×GDP per capita), between 3×GDP per capita and 1×GDP per capita in six nations (Kenya, Tonga, Kiribati, Samoa, Micronesia, Comoros), and highly cost effective in all other nations (fig 2). Indeed, in 130 countries, representing more than 96% of the world’s population, the estimated cost effectiveness ratio was <0.1×GDP per capita, far below usual cost effectiveness thresholds. This included each of the world’s 20 most populous countries (fig 3).

Fig 2 Cost effectiveness (purchasing power adjusted I$/disability adjusted life year (DALY) as a multiple of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita) by country of a national policy intervention to reduce sodium consumption by 10%

Fig 3 Affordability of a national policy intervention to reduce sodium consumption by 10% in the world’s 20 most populous countries. Each point represents the cost effectiveness of the intervention (I$/disability adjusted life year (DALY)) for a given country against that country’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (I$), adjusted for purchasing power. The lines represent 0.01×, 0.05×, and 0.1×GDP per capita, selected as reasonable fractions against which to compare our estimates of affordability. Notably, each of these thresholds is substantially lower than the World Health Organization benchmarks for an intervention being cost effective (<3.0×GDP per capita) or highly cost effective (<1.0×GDP per capita). For example, Nigeria and Bangladesh, being to the right of the blue line and to the left of the red dotted line, have a cost effectiveness ratio less than 0.1×GDP per capita but greater than 0.05×GDP per capita

Potential heterogeneity of effectiveness and costs

A national policy intervention to reduce sodium intake remained highly cost effective globally and by world region when we considered alternative effectiveness (proportional reduction of 30%, absolute reduction of 0.5 g/day or 1.5 g/day); and alternative thresholds of optimal intake (the level at which further sodium reduction produces no further health benefits) of 3.0 g/day or 1.0 g/day (table 2). Generally, achieving larger sodium reduction targets (eg, 30%, 1.5 g/day) was more cost effective (see supplementary eFigure 2), but even modest achieved reductions (10% or 0.5 g/day over 10 years) were highly cost effective. Under any of these scenarios, the estimated cost effectiveness ratio was <0.05×GDP per capita in nearly every world region. In Sub-Saharan Africa, owing to generally low sodium intakes in that region, the estimated cost effectiveness ratio was <0.1×GDP per capita when the optimal intake threshold was 1.0 g/day or 2.0 g/day, but up to 6.0×GDP per capita when it was assumed to be 3.0 g/day.

Table 2.

Variation in cost effectiveness depending on heterogeneity of both intervention efficacy and optimal level of sodium intake by income and geographic region.* Values are I$/disability adjusted life years (DALYs) unless stated otherwise

| Variables | Per capita (I$) | 0.05×GDP/capita (I$) | Optimal sodium intake 1 g/day | Optimal sodium intake 2 g/day | Optimal sodium intake 3 g/day | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention cost | GDP | 10% | 30% | 0.5 g | 1.5 g | 10% | 30% | 0.5 g | 1.5 g | 10% | 30% | 0.5 g | 1.5 g | ||||

| World | 1.13 | 13 553 | 678 | 202 (155 to 307) | 66 (50 to 102) | 158 (121 to 241) | 51 (39 to 78) | 204 (149 to 322) | 72 (52 to 119) | 160 (117 to 251) | 60 (43 to 99) | 7572 (1549 to 238 812) | 7217 (1174 to 219 444) | 14 013 (1401 to 228 971) | 3952 (1527 to 221 668) | ||

| High income† | 2.03 | 38 818 | 1941 | 480 (365 to 731) | 156 (118 to 242) | 378 (288 to 583) | 122 (93 to 188) | 465 (341 to 724) | 156 (114 to 251) | 369 (270 to 573) | 126 (92 to 199) | 511 (371 to 831) | 198 (140 to 327) | 410 (291 to 693) | 176 (125 to 292) | ||

| Upper middle income | 1.06 | 11 001 | 550 | 150 (117 to 224) | 49 (37 to 74) | 127 (99 to 190) | 41 (32 to 61) | 146 (109 to 223) | 49 (37 to 78) | 123 (92 to 186) | 44 (32 to 67) | 192 (133 to 346) | 89 (57 to 185) | 162 (110 to 319) | 85 (55 to 194) | ||

| Lower middle income | 0.72 | 4115 | 206 | 113 (86 to 174) | 37 (28 to 58) | 82 (63 to 125) | 26 (20 to 41) | 111 (81 to 175) | 38 (28 to 61) | 81 (59 to 127) | 30 (21 to 48) | 150 (101 to 271) | 68 (43 to 138) | 113 (75 to 217) | 63 (40 to 130) | ||

| Low income | 0.80 | 1456 | 73 | 130 (97 to 207) | 43 (32 to 69) | 75 (56 to 117) | 27 (20 to 44) | 215 (139 to 400) | 110 (68 to 212) | 142 (93 to 266) | 101 (61 to 208) | 87 264 (16 506 to 2 832 119) | 84 582 (13 187 to 2 604 509) | 16 4290 (15 143 to 2 715 885) | 48 004 (17 437 to 2 630 998) | ||

| Australia and New Zealand | 2.63 | 40 181 | 2009 | 891 (675 to 1358) | 292 (218 to 451) | 622 (465 to 954) | 203 (152 to 315) | 880 (646 to 1382) | 300 (215 to 477) | 621 (455 to 955) | 221 (159 to 344) | 1037 (755 to 1675) | 427 (305 to 691) | 753 (538 to 1238) | 374 (269 to 586) | ||

| Canada and US | 1.67 | 48 940 | 2447 | 361 (275 to 543) | 118 (89 to 178) | 264 (201 to 405) | 86 (65 to 132) | 350 (257 to 537) | 118 (87 to 187) | 259 (190 to 399) | 89 (66 to 138) | 389 (287 to 616) | 153 (111 to 245) | 294 (210 to 483) | 133 (96 to 212) | ||

| Central Asia/Eastern and Central Europe | 2.59 | 14 833 | 742 | 220 (170 to 330) | 72 (54 to 109) | 185 (143 to 279) | 60 (46 to 90) | 211 (157 to 324) | 70 (52 to 112) | 179 (133 to 270) | 60 (44 to 91) | 220 (161 to 349) | 81 (58 to 129) | 188 (136 to 308) | 73 (53 to 117) | ||

| East and Southeast Asia | 0.82 | 10 777 | 539 | 130 (102 to 190) | 42 (33 to 62) | 124 (97 to 183) | 40 (31 to 59) | 123 (93 to 184) | 40 (31 to 63) | 118 (89 to 174) | 39 (29 to 59) | 129 (94 to 214) | 48 (33 to 87) | 122 (88 to 209) | 47 (33 to 88) | ||

| Latin America and Caribbean | 0.87 | 12 505 | 625 | 233 (176 to 358) | 76 (57 to 120) | 151 (116 to 235) | 50 (37 to 77) | 236 (171 to 375) | 83 (60 to 137) | 157 (114 to 249) | 64 (46 to 104) | 415 (271 to 795) | 228 (136 to 504) | 309 (196 to 705) | 217 (130 to 549) | ||

| North Africa and Middle East | 1.33 | 12 436 | 622 | 314 (234 to 501) | 102 (76 to 167) | 253 (190 to 409) | 81 (60 to 130) | 300 (215 to 490) | 100 (71 to 173) | 245 (177 to 406) | 84 (59 to 139) | 325 (227 to 563) | 123 (83 to 216) | 268 (184 to 482) | 111 (76 to 196) | ||

| South Asia | 0.74 | 3551 | 178 | 121 (92 to 187) | 40 (30 to 61) | 91 (70 to 140) | 29 (22 to 45) | 116 (85 to 182) | 39 (29 to 62) | 88 (65 to 138) | 30 (22 to 48) | 126 (91 to 205) | 49 (34 to 79) | 98 (69 to 167) | 42 (30 to 70) | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1.01 | 2769 | 138 | 161 (120 to 256) | 53 (39 to 85) | 80 (59 to 122) | 30 (22 to 48) | 255 (166 to 473) | 127 (80 to 242) | 155 (101 to 289) | 115 (70 to 236) | 88 269 (16 762 to 2 859 366) | 85 502 (13 376 to 26 29504) | 165 968 (15 351 to 2 741 935) | 48 337 (17 666 to 2 656 245) | ||

| Western Europe | 2.00 | 35 676 | 1784 | 489 (371 to 742) | 160 (120 to 246) | 374 (283 to 573) | 121 (92 to 186) | 477 (350 to 744) | 160 (118 to 256) | 367 (268 to 565) | 126 (92 to 197) | 528 (387 to 845) | 205 (146 to 329) | 412 (294 to 687) | 180 (128 to 288) | ||

GDP=gross domestic product.

*A national government supported sodium reduction intervention may have differing effectiveness in different settings. To test the robustness of findings to different assumptions, varying effectiveness levels were evaluated—including 10% and 30% proportional reductions and 0.5 g/day and 1.5 g/day absolute reductions in sodium intake. In addition, the optimal level of sodium intake remains uncertain. 1.0 g/day, 2.0 g/day, and 3.0 g/day were evaluated as varying optimal levels of sodium intake: the threshold at which further reductions in intake lead to no further cardiovascular disease benefits.

†Income categorizations are based on the World Bank classification system (http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups).

As expected, cost effectiveness ratios were sensitive to variations in estimated intervention cost. We evaluated the proportion of the world’s adult population living in countries with a cost effectiveness ratio (I$/DALY) <0.05×GDP per capita and <0.5×GDP per capita, for varying intervention costs that were 25%, 50%, 150%, 200%, or 500% of baseline cost estimates (see supplementary eFigure 3). For a 10% reduction in sodium intake, under the base case scenario for cost estimates, 89% of the global adult population would live in countries with a cost effectiveness ratio <0.05×GDP per capita. This decreased to 23% of the global adult population if costs were fivefold higher, 68% if costs were twofold higher, and 85% if costs were 1.5-fold higher. In contrast, 96% of the global adult population would live in countries with a cost effectiveness ratio <0.05×GDP per capita if costs were half as large, and 99% if costs were one quarter as large. For a 30% reduction in sodium intake, the corresponding figures for a benchmark of <0.05×GDP per capita were 85%, 92%, 96%, 98%, 99.1%, and 99.3% of the global adult population based on intervention costs that were 500%, 200%, 150%, 50%, or 25% of the baseline cost estimates, respectively. We also made comparisons against a cost effectiveness ratio benchmark <0.5×GDP per capita, still substantially below the WHO criterion of 1×GDP per capita as highly cost effective. For a 10% reduction in sodium intake, even if the intervention costs were fivefold greater than the baseline estimate, 96% of the world’s population would live in countries with a cost effectiveness ratio <0.5×GDP per capita; and for a 30% reduction in sodium intake, 99% would.

Discussion

We found that a government “soft regulation” policy intervention to reduce national sodium consumption by 10% over 10 years was projected to be highly cost effective in nearly every country in the world (<1×gross domestic product (GDP) per capita per disability life year (DALY) saved), and remarkably cost effective (<0.05×GDP per capita per DALY) in most countries. Hundreds of thousands of deaths, and millions of DALYs, were estimated to be potentially averted annually, at low cost.

Comparison with other prevention strategies

These cost effectiveness ratios compare very favorably with other prevention strategies. For example, “best buy” pharmacologic interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease in high income countries have much higher estimated cost effectiveness ratios, such as $21 000/DALY or more for primary prevention with statin drugs and $6000/DALY or more for secondary prevention with β blockers.32 33 By contrast, for this national government supported intervention to reduce sodium intake by 10% over 10 years, we project an average cost effectiveness ratio of I$465/DALY in high income countries. Similarly, our projected cost effectiveness ratio of I$143/DALY in low income and middle income countries compares favorably with an estimated cost effectiveness ratio of I$900/DALY for a cardiovascular disease combination pill (“polypill”) targeted at high risk people in developing countries.34 Notably, most of these prior pharmacologic cost effectiveness ratios included estimated health savings from averted cardiovascular disease events, which produces substantially more favorable cost effectiveness ratios than if estimated health savings are omitted, as in our analysis.33 34

Our novel results, together with prior studies in selected countries,5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 provide evidence that a national policy for reduction in sodium intake is highly cost effective, and substantially more so than even highly cost effective medical prevention strategies. This advantage likely arises from several factors. This policy is relatively inexpensive to implement, utilizing system wide “soft regulation” rather than provision of individual level medical care. It also decreases cardiovascular risk at a population level, such that even small changes in distributions of risk factors translate into large clinical benefits,35 as compared with more intensive strategies delivered only to a subset of people. Thus, there are meaningful “returns to scale” on both the cost side and the effect side. This suggests that a national reduction in sodium intake is a “best buy” for governments, deserving careful consideration for adoption by countries worldwide.

Despite differences in modeling methods, other studies of sodium reduction interventions in selected nations have also found them to be extremely cost effective.5 9 10 11 13 Many of these prior analyses incorporated estimated health system savings from averted cardiovascular disease events, which generally rendered the interventions not only cost effective but also actually cost saving—that is, with dominant cost effectiveness ratios less than zero. For example, one analysis in the US estimated that a 0.4 g/day (about 11%) sodium reduction over 10 years would save from $4bn to $7bn in healthcare costs.10 Some analyses further accounted for productivity gains from reduced morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease, further increasing cost savings. Investigations that, like ours, calculated only intervention costs and DALYs averted, without including any estimates of health system savings, arrived at similar cost effectiveness ratios for comparable regions (eg, I$561 for western Europe36 versus our cost effectiveness ratio of I$477 in that region).

Our investigation builds on and substantially extends such prior analyses of potential sodium reduction interventions in several important respects. First, most included only a single high income nation.5 10 11 13 One prior analysis included 23 more varied nations but only estimated averted deaths, rather than DALYs,7 preventing comparison with other cost effectiveness ratios. In contrast with prior analyses, we also jointly incorporated heterogeneity in blood pressure effects of sodium reduction by age, race, and hypertensive status, providing more accurate estimates for the impact on cardiovascular disease. Additionally, our analysis of 183 countries using consistent methods enabled us to explore sources of heterogeneity and sensitivity in estimated cost effectiveness across diverse nations and regions.

Sources of heterogeneity

Differences in intervention costs were one of the major drivers of varying cost effectiveness ratios. The large variation of human resource and mass media costs across countries suggests potential savings from multinational efforts to reduce sodium intake, which could benefit from economies of scale. For instance, the new European Union Salt Reduction Framework, which monitors national sodium reduction initiatives and supports implementation efforts across multiple member nations,4 could be emulated elsewhere. Consistent with the relevance of scale, the 20 countries with highest per capita intervention costs all had national populations of less than 500 000 adults. The higher cost of mass media, compared with other intervention components, further suggests a need for research on how best to target such resources. The recent finding37 that salt reduction in the UK arose largely from product reformulation rather than changes in consumer choice suggests that, in countries where most dietary sodium comes from processed food (eg, 77% in the US38), the robustness and compliance with industry targets may be more relevant than mass media components. On the other hand, public awareness of sodium in foods and health effects could be essential for generating sufficient public and policy maker pressure on industry to meet stated targets. In nations with lower proportions of manufactured food, industry focused efforts might lead to smaller absolute reductions in sodium intake. Yet many such countries also have lower baseline levels of sodium consumption,1 so that proportional reductions might be similar. In comparison, for certain Asian nations such as China, substantial amounts of sodium are added at home, making education and media efforts more relevant. Nevertheless, even with an up to fivefold increase in total costs, our multinational investigation suggests that a government supported program to reduce sodium intake would be highly cost effective for nearly every country in the world.

Our findings were robust to differing thresholds for optimal sodium intake. While the precise optimal level of sodium intake remains uncertain,25 to our knowledge ours is the first cost effectiveness analysis to evaluate the relevance of this uncertainty to policy. We found that this threshold influences relative cost effectiveness only in countries with the lowest intakes, with little effect in most others. For example, cost effectiveness ratios increase notably in Sub-Saharan Africa when the threshold is raised from 2.0 g/day to 3.0 g/day, but relatively little in most other nations (table 2).

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our analysis has several strengths. The model used comparable and consistent methods to estimate cost effectiveness in 183 countries, including contemporary data on age, sex, and nation specific distributions of sodium consumption, blood pressure, and rates of cardiovascular disease. Blood pressure effects of sodium reduction were derived from meta-analysis of randomized trials, accounting for differences by age, race, and hypertension; and the cardiovascular effects of blood pressure lowering from pooled analysis of prospective studies, accounting for age. The modeled intervention included a realistic scale-up trajectory and target sodium reduction. The cost estimates incorporated country specific demographic, economic, and health data, together with results from cross country non-traded input price regressions, to produce credible estimates of national prices. We incorporated uncertainty in multiple input parameters (measures of sodium exposure, distributions of blood pressure, effects of sodium on blood pressure, effects of blood pressure on cardiovascular disease) by multi-way probabilistic Monte Carlo simulations, and additional uncertainty in intervention effectiveness and intervention costs by separate sensitivity analyses.

Potential limitations should be considered. The estimates of sodium consumption, blood pressure levels, and rates of cardiovascular disease were based on raw data covering most but not all of the global population, with hierarchical estimation of the remainder.1 39 40 Our estimates of health benefits accounted only for cardiovascular disease, whereas high sodium intake is also associated with vascular stiffness, renal dysfunction, and stomach cancer, independent of blood pressure levels.41 42 43 We did not account for possible unintended consequences of the intervention, such as changes in population choices of overall foods consumed. We did not model health system savings from averted cardiovascular disease events. Better cardiovascular health may produce compression of disease and costs into the last years of life, reducing overall morbidity and lifetime costs, but modeling such potential health transitions and treatment costs for every nation globally is not yet feasible. We did not evaluate potential effects on disparities within countries; for instance, food product reformulation to reduce sodium intake in England has been estimated to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular disease.44 Our models are based on a 10 year intervention period including planning, development, and staged implementation. Over the longer term, intervention costs may decrease, while lifetime health benefits might also increase. Thus, these findings should be considered a platform on which to base intermediate term policies, recognizing that longer term effectiveness should also be evaluated. Our assumptions about intervention implementation may differ in various real world situations, producing larger or smaller costs and effect sizes. However, our analyses of the sensitivity of our findings to variations in costs and effectiveness demonstrated that overall cost effectiveness was highly robust to alternative assumptions. We did not evaluate other potential strategies to reduce sodium intake, such as mandatory quality standards, taxation, complementary state or community initiatives, or multi-component approaches, such as seen in Japan and Finland.45 46 47 These might produce similar or even greater reductions in sodium intake at less cost, but are also perhaps less feasible in certain nations.

Conclusions

Even without incorporating potential healthcare savings from averted events, we found that a government supported, coordinated national policy to reduce population sodium intake by 10% over 10 years would be cost effective in all and extremely cost effective in nearly all of 183 nations evaluated.

What is already known on this topic

In prior research in a limited number of high income nations, national policies to reduce excess sodium intake have been estimated to be highly cost effective for reducing hypertension and cardiovascular disease

For most countries, the cost effectiveness of a national policy intervention to reduce sodium intake is unknown

What this study adds

We found that a government “soft regulation” strategy combining targeted industry agreements and public education to reduce population sodium intake by 10% over 10 years would be extremely cost effective in nearly all of 183 nations evaluated

This would result in an average cost effectiveness ratio (not accounting for potential healthcare savings from averted events) of I$204/disability adjusted life year

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: Supplementary material

We thank the World Health Organization for use of the Noncommunicable Disease Costing Tool, and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation for use of their cardiovascular disease DALY estimates.

Contributors: MW and DM conceptualised the study and wrote the final draft of the paper; DM also provided funding support and supervision. MW undertook the analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. SF, GMS, SK, and RM prepared data and commented on the paper. JP commented on the paper. All authors approved the final version. MW acts as guarantor of the study.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL115189; principal investigator DM) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (T32 training grant in academic nutrition, DK007703; GMS), National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: financial support from the National Institutes of Health for the submitted work. DM reports ad hoc honorariums or consulting fees from Boston Heart Diagnostics, Haas Avocado Board, Astra Zeneca, GOED, DSM, and Life Sciences Research Organization, none of which were related to topics of dietary sodium. The other authors report no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: The global data on sodium intake may be requested from the authors for academic collaborations; see www.globaldietarydatabase.org/requesting-data.html. Global data on blood pressure is available for download at www1.imperial.ac.uk/publichealth/departments/ebs/projects/eresh/majidezzati/healthmetrics/metabolicriskfactors/metabolic_risk_factor_maps/ Global data on cardiovascular events is available for download from the Global Burden of Diseases Study at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/global-burden-disease-study-2013-gbd-2013-data-downloads.

Transparency: The lead author (MW) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1.Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, et al. Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group (NutriCoDE). Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide.BMJ Open 2013;3:e003733 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003733. pmid:24366578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, et al. Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes.N Engl J Med 2014;371:624-34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1304127. pmid:25119608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenstein AH, Ausman LM, Carrasco W, Jenner JL, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ. Hypercholesterolemic effect of dietary cholesterol in diets enriched in polyunsaturated and saturated fat. Dietary cholesterol, fat saturation, and plasma lipids. Arterioscler Thromb 1994;14:168-75. 10.1161/01.ATV.14.1.168 pmid:8274473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Commission. Survey on Member States' Implementation of the EU Salt Reduction Framework. http://ec.europa.eu/health/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/salt_report1_en.pdf (accessed 28 May, 2016).

- 5.Selmer RM, Kristiansen IS, Haglerod A, et al. Cost and health consequences of reducing the population intake of salt. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:697-702. 10.1136/jech.54.9.697 pmid:10942450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abelson P. Returns on investment in public health: an epidemiological and economic analysis prepared for the Department of Health and Ageing.Department of Health and Ageing, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asaria P, Chisholm D, Mathers C, Ezzati M, Beaglehole R. Chronic disease prevention: health effects and financial costs of strategies to reduce salt intake and control tobacco use.Lancet 2007;370:2044-53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61698-5. pmid:18063027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penz ED, Joffres MR, Campbell NR. Reducing dietary sodium and decreases in cardiovascular disease in Canada. Can J Cardiol 2008;24:497-1. 10.1016/S0828-282X(08)70625-1 pmid:18548148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palar K, Sturm R. Potential societal savings from reduced sodium consumption in the U.S. adult population.Am J Health Promot 2009;24:49-57. 10.4278/ajhp.080826-QUAN-164. pmid:19750962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2010;362:590-9. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907355 pmid:20089957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith-Spangler CM, Juusola JL, Enns EA, Owens DK, Garber AM. Population strategies to decrease sodium intake and the burden of cardiovascular disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med 2010;152(8):481-7, W170-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cobiac LJ, Vos T, Veerman JL. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to reduce dietary salt intake.Heart 2010;96:1920-5. 10.1136/hrt.2010.199240. pmid:21041840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barton P, Andronis L, Briggs A, McPherson K, Capewell S. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of cardiovascular disease prevention in whole populations: modelling study.BMJ 2011;343:d4044 10.1136/bmj.d4044. pmid:21798967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertram MY, Steyn K, Wentzel-Viljoen E, Tollman S, Hofman KJ. Reducing the sodium content of high-salt foods: effect on cardiovascular disease in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2012;102:743-5. 10.7196/SAMJ.5832 pmid:22958695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UK Food Standards Agency. UK Salt Reduction Initiatives. www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/multimedia/pdfs/saltreductioninitiatives.pdf (accessed 28 May, 2016).

- 16.Johns B, Baltussen R, Hutubessy R. Programme costs in the economic evaluation of health interventions. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2003;1:1 10.1186/1478-7547-1-1 pmid:12773220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Summers R, Heston A. The Penn World Table (Mark 5): an expanded set of international comparisons, 1950-1987. Q J Econ 1991;106:327-68 10.2307/2937941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meltzer D. 42 Future costs in medical cost-effectiveness analysis. The Elgar companion to health economics 2012:447 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB. Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA 1996;276:1253-8. 10.1001/jama.1996.03540150055031 pmid:8849754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadler K, Nicholson S, Steer T, et al. National Diet and Nutrition Survey - Assessment of dietary sodium in adults (aged 19 to 64 years) in England, 2011.UK Department of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.News WHO. Progress in reducing salt consumption in Turkey. www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/news/news/2013/04/progress-in-reducing-salt-consumption-in-turkey (accessed 28 May, 2016).

- 22.O’Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, et al. PURE Investigators. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events[Online First: Epub Date] |.].N Engl J Med 2014;371:612-23. 10.1056/NEJMoa1311889. pmid:25119607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cobb LK, Anderson CA, Elliott P, et al. American Heart Association Council on Lifestyle and Metabolic Health. Methodological issues in cohort studies that relate sodium intake to cardiovascular disease outcomes: a science advisory from the American Heart Association.Circulation 2014;129:1173-86. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000015. pmid:24515991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook NR, Appel LJ, Whelton PK. Lower levels of sodium intake and reduced cardiovascular risk. Circulation 2014;129:981-9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006032. pmid:24415713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Institute of Medicine. Sodium Intake in Populations: Assessment of Evidence.The National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Institute of Medicine. Evaluation of Biomarkers and Surrogate Endpoints in Chronic Disease.National Academies Press, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002;360:1903-13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11911-8 pmid:12493255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al. SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Adults Aged ≥75 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;315:2673-82. 10.1001/jama.2016.7050. pmid:27195814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis.Lancet 2016;387:435-43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00805-3. pmid:26559744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and health: Investing in health for economic development.World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marseille E, Larson B, Kazi DS, Kahn JG, Rosen S. Thresholds for the cost-effectiveness of interventions: alternative approaches.Bull World Health Organ 2015;93:118-24. 10.2471/BLT.14.138206. pmid:25883405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldman L, Sia ST, Cook EF, Rutherford JD, Weinstein MC. Costs and effectiveness of routine therapy with long-term beta-adrenergic antagonists after acute myocardial infarction.N Engl J Med 1988;319:152-7. 10.1056/NEJM198807213190306. pmid:2898733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldman L, Weinstein MC, Goldman PA, Williams LW. Cost-effectiveness of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition for primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA 1991;265:1145-51. 10.1001/jama.1991.03460090093039 pmid:1899896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaziano T. Prevention and treatment of chronic diseases in developing countries. Expert Paper No. 2011/2: UN Dept of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, 2011.

- 35.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:427-32, discussion 433-4. 10.1093/ije/30.3.427 pmid:11416056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray CJ, Lauer JA, Hutubessy RC, et al. Effectiveness and costs of interventions to lower systolic blood pressure and cholesterol: a global and regional analysis on reduction of cardiovascular-disease risk.Lancet 2003;361:717-25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12655-4. pmid:12620735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffith R, O’Connell M, Smith K. The importance of product reformulation versus consumer choice in improving diet quality. IFS Working Paper W14/15, 2014.

- 38.Mattes RD, Donnelly D. Relative contributions of dietary sodium sources. J Am Coll Nutr 1991;10:383-93. 10.1080/07315724.1991.10718167 pmid:1910064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lin JK, et al. Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Blood Pressure). National, regional, and global trends in systolic blood pressure since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 786 country-years and 5·4 million participants.Lancet 2011;377:568-77. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62036-3. pmid:21295844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197-223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 pmid:23245608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP, Meerpohl JJ. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta-analyses.BMJ 2013;346:f1326 10.1136/bmj.f1326. pmid:23558163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graudal NA, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jurgens G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride.Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(11):CD004022 10.1002/14651858.CD004022.pub3. pmid:22071811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joossens JV, Hill MJ, Elliott P, et al. European Cancer Prevention (ECP) and the INTERSALT Cooperative Research Group. Dietary salt, nitrate and stomach cancer mortality in 24 countries. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:494-504. 10.1093/ije/25.3.494 pmid:8671549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillespie DO, Allen K, Guzman-Castillo M, et al. The Health Equity and Effectiveness of Policy Options to Reduce Dietary Salt Intake in England: Policy Forecast.PLoS One 2015;10:e0127927 10.1371/journal.pone.0127927. pmid:26131981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christoforou A, Trieu K, Land MA, Bolam B, Webster J. State-level and community-level salt reduction initiatives: a systematic review of global programmes and their impact.J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:1140-50. 10.1136/jech-2015-206997. pmid:27222501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trieu K, Neal B, Hawkes C, et al. Salt Reduction Initiatives around the World - A Systematic Review of Progress towards the Global Target. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130247 10.1371/journal.pone.0130247. pmid:26201031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hyseni L, Elliot-Green A, Lloyd-Williams F, et al. Systematic review of dietary salt reduction policies: evidence for an effectiveness hierarchy?[abstract] Circulation 2016;133(Suppl 1):154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: Supplementary material