Abstract

Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs) are a major public health issue worldwide. Although drinking and problematic alcohol use usually begins during adolescence, developmental origins of the disorder can be traced back to infancy and early childhood. Identification of early risk factors is essential to understanding developmental origins. Using data from the Michigan Longitudinal Study, an ongoing, prospective, high-risk family study, this paper summarizes findings of family context and functioning of both children and parents. We draw attention to the development of the self, an understudied aspect of very young children being reared in alcoholic families that exacerbates exposure to high childhood adverse experiences. We also provide evidence demonstrating that young boys are embedded in a dynamic system of genes, epigenetic processes, brain organization, family dynamics, peers, community, and culture that strengthens risky developmental pathways if nothing is done to intervene during infancy and early childhood.

Keywords: Alcohol Use Disorders, Risk, Developmental Pathways, Externalizing Behavior, Intersubjective Self

Harmful use of alcohol results in disease, as well as significant social and economic burden worldwide (WHO, 2014). In fact, the 2014 World Health Organization Global Status Report estimated that there were 3.3 million deaths, (5.9 % of all global deaths) attributable to alcohol consumption in 2012, and the overall global burden of disease and injury from alcohol use was 5.1%. Historically, the study of Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs) focused on adults, with emphasis on the origins of AUDs as emergent in adolescence. Beginning in the latter part of the 20th century, numerous longitudinal studies with origins in infancy and early childhood began to provide empirical evidence that the etiology of antisocial behavior (Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter, & Silva, 2001), aggression and violence (Shaw & Gilliam, 2016), conduct disorder (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2013), borderline personality disorder (Fonagy, Luyten & Strathearn, 2011), alcohol use disorders (Eiden, Edwards & Leonard, 2007), and attachment disorders (Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson & Collins, 2005) may be grounded in organizational dynamics that first show up in infancy and early childhood. With regard to AUDs, research from the past several decades also focused attention on developmental origins that can be traced to the period of infancy and early childhood (Zucker, 2014; Zucker et al., 2006), with actual drinking onset starting during the transitional years from childhood to adolescence (Donovan et al, 2004; Zucker et al., 2006).

In this article, we draw upon mostly previously published data from the Michigan Longitudinal Study (MLS; Zucker et al. 2000) to provide insights into risk factors for boys, particularly those who are exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in relation to parental drinking and co-morbid psychopathology (Loukas, Fitzgerald, Zucker, & von Eye, 2001; Poon, Ellis, Fitzgerald & Zucker, 2000), and family dynamics (Ellis, Zucker & Fitzgerald, 1997). We first provide a brief overview of AUD as an introduction to the MLS. We then summarize findings from the MLS within the context of family dynamics and child functioning, with a larger discussion of the development of the self and cognitive schema because they are understudied components in the alcohol literature. While exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACE) affects both boys and girls (e.g. Fitzgerald, Zucker, Puttler, Caplan & Mun, 2000), our focus in this article is on boys at risk for AUDs and co-morbid psychopathology because the problems are still about twice as likely in boys, and perhaps more importantly, because the dynamics of these relationships appear to be less complex and are somewhat better understood than they are for girls (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). Nolen-Hoeksema suggested that there appears to be an absence of many of the risk factors for alcohol use and abuse for girls than for boys, as well as a greater sensitivity to the negative consequences for females.

As defined in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) is the current nomenclature for misuse of alcohol. The disorder involves a problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to significant distress and requiring two of a possible 11 symptoms co-occurring within a 12-month period to meet diagnostic criteria (see Table 1). In the United States, using data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III; Grant et al., 2014) national estimates of the prevalence of AUDs for adults 18 and over during 2012 and 2013 was 13.9% for the past 12 months, and 29.1% for a lifetime diagnosis (Grant et al. 2015). The prevalence of AUDs are highest during the emerging adult years (18-29), and importantly to this special journal edition regarding “Boys at Risk”, AUDs are still more common among men than women with adjusted odds ratios of approximately two to one (Grant et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Eleven Symptoms of Alcohol Use Disorder. Mild AUD (presence of 2-3 symptoms), Moderate (4-5 symptoms), Severe (6 or more symptoms).

| 1. Alcohol is consumed in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended. |

| 2. There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful effort to reduce or control alcohol use. |

| 3. Significant time is spent trying to obtain alcohol, use it, recover from its effects. |

| 4. Individual craves or has a strong desire or urge to use alcohol. |

| 5. Alcohol use results in a failure to meet obligations at work, school, or home. |

| 6. Continued alcohol use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of alcohol. |

| 7. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol use. |

| 8. Individual continues to use alcohol in situations that are physically hazardous. |

| 9. Alcohol use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrephysical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by alcohol. |

| 10. Tolerance: |

| 1. A need for markedly increased amounts of alcohol to achieve desired effect |

| 2. A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of alcohol. |

| 11. Withdrawal syndrome is experienced. |

Adapted from the American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

It was not until the 1980s that a paradigm shift began, with investigators positing that AUDs emerged from developmental pathways beginning, or at least identifiable, as early as infancy rather than when they might be expressed during early adolescence (Zucker, 2014). Towards the end of this decade, several longitudinal studies began of children at risk for alcohol and substance use disorders due to a positive family history of alcohol problems; a significant risk factor for adult AUDs (see Chassin, Rogosch, & Barrera, 1991; Sher & Rutledge, 2007; and Zucker et al., 2000 for descriptions of three such studies). This developmental perspective stimulated exploration of the pathways of risk for early antecedents and intervening mechanisms of AUDs (Hussong et al., 2007), including pathways that included equifinal, as well as multifinal outcomes. Equifinality refers to different pathways leading to the same endpoint (in this case, AUD), and multifinality refers to the same pathway resulting in different expressed outcomes (such as AUD, delinquency, antisocial behavior, or combinations of co-morbid psychopathologies). Our current understanding of these pathways suggest that facing many individuals who go on to develop AUDs is a complex and dynamic system of genes, epigenetic processes, brain, family, peers, community, and culture. This system undergoes change as development proceeds and enhances the risk for future problems in these individuals if nothing is done to disrupt the risky pathways. Thus, both equifinal and multifinal pathways are operative.

The Michigan Longitudinal Study (MLS)

The Michigan Longitudinal Study (MLS: Zucker et al., 2000), is a prospective, high-risk for AUD, other substance use disorders (SUD), and co-morbid psychopathology family study that began in the mid-1980s and is still ongoing. The MLS was originally conceived as an opportunity to follow children and their parents longitudinally even before birth, but was for logistical and epidemiological reasons later changed to start with a focus on preschool aged boys. The early specific aims were to map the evolution of risk and protective factors involved in the development of AUDs, to identify the evolution of alcohol specific learning in young children, to explore the development of risk among alcoholic subtypes, and to specify the determinants of diverse pathways over the lifespan. It was expected that as we gained such understanding, policy making would be influenced and new prevention and intervention programs would be established.

In order to achieve these goals, risk level of the offspring in the MLS was varied through recruitment of a population-based sample that differed in level of AUD among the fathers (Zucker et al., 2000). The highest risk group of the 466 families recruited into the study had a father who was a drunk driver at initial recruitment with at least a 0.15% blood alcohol level, recruited from all district courts blanketing four counties within mid-Michigan. Other inclusionary criteria were that the parents be currently coupled and have a 3-5 year old son who was the biological child of both parents. The medium risk group was uncovered during neighborhood canvassing for control families and included fathers meeting AUD criteria, with both parents again coupled and having a 3-5 year old biological son. In both the court and community recruited alcoholic groups, the mother's history of having a substance use disorder was free to vary. The lowest risk group was an ecologically comparable set of control families accessed via door-to-door canvassing in the same neighborhoods where the court alcoholics lived. However, for this group neither parent met criteria for an AUD or SUD as an adult. Again, the parents needed to be coupled and have a 3-5 year old biological son. Subsequently, all full biological male and female children of the two parents from all three groups who were within eight years of age of the original targeted preschool age son were enrolled.

The MLS involves repeated measurement for all family members of behavioral and psychological functioning, environment, substance use and problems of use, and psychiatric symptoms. Full wave assessments take place every three years. In order to shorten an otherwise three-year retrospective report, an annual assessment on just the youth occurs between the ages of 11 and 23 for a subset of important variables. The comprehensive measurement model was designed to evaluate multiple content areas for all study participants, at multiple time points, that would allow for comparisons of continuities and discontinuities over time, and that could take into account normative developmental progression. In addition to psychosocial data, as the study continued additional data collection began probing neuropsychological functioning (primarily executive functioning), brain functioning through the use of fMRI (in order to understand the neural systems underlying risk), genetic markers of risk (assessed via blood or saliva assays), and a small study of sleep functioning in a subset of the children. Currently, the majority of the original targeted sons are now aged 27 – 35, although many are still younger along with many of the later recruited siblings.

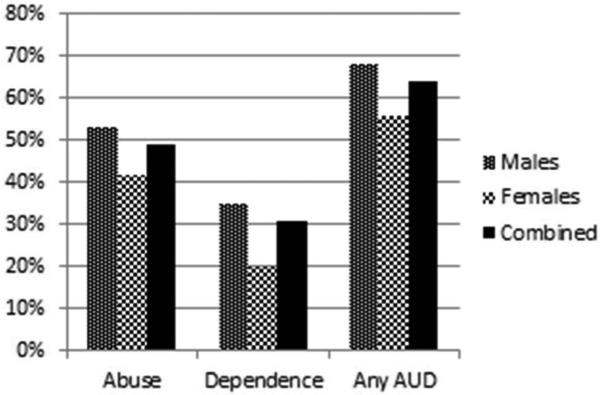

Before moving into the findings from the earlier years of the MLS, it is worth taking a quick look at the level of AUDs in the MLS child sample as they enter into early adulthood. Figure 1 shows the rates of DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) diagnosis at ages 18-23 for study participants who have reached at least age 23 to date. At these ages, 49% of the sample (53% for males, 42% for females) make a positive diagnosis for Alcohol Abuse, 31% (35% for males, 20% for females) make a diagnosis of Alcohol Dependence, and 64% of the sample (68% for males, 56% for females) make a positive diagnosis for an AUD (either Abuse and/or Dependence during that age range). These data are from 534 current participants, about a fourth of the child sample. Not surprisingly due to the high-risk design of the MLS, the AUD among MLS participants is much higher than the national rates of 18-29 year olds from the general U. S. population in the early 2000s where about 7% met abuse criteria and 9% met dependence criteria (Grant et al., 2006), and the higher male to female ratio usually found in population studies is not as large in the MLS sample.

Figure 1.

Rates of DSM-IV Alcohol Use Disorders in MLS Young Adults ages 18-23

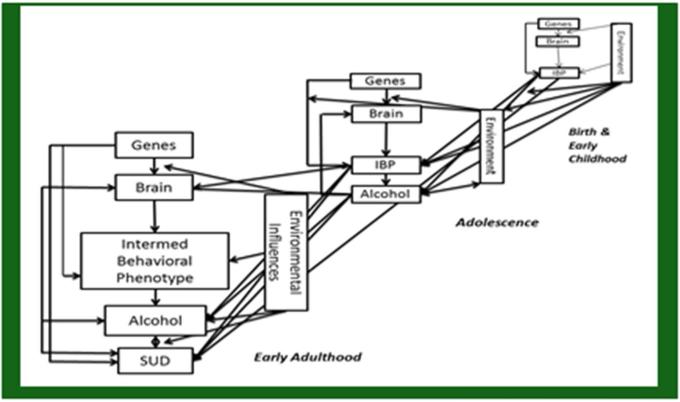

To expose the reader to the complexity of what can take place developmentally to reach these levels of AUDs, Figure 2 shows a heuristic model involving multiple levels of influence at each stage and across time (Zucker, Hicks, & Heitzeg, 2016). The model involves genes, brain response/reactivity systems, intermediate alcohol non-specific phenotypes (encompassing personality/temperament and behavior), and environmental influences leading first to the initiation of alcohol use and culminating in the occurrence of an AUD (depicted as SUD since AUD is but one of the SUDs). Taking a step back, however, we turn next to examine data that helped contribute to the development of the model depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow over Time of a Heuristic Model of Developmental Systems Framework for the Development of Alcohol Use Disorder

Family Context Impact during the Child's Preschool Years

It is well known that the impact of living in a stressful family environment has the potential to negatively impact child development (Fitzgerald, Puttler, Refior & Zucker, 2007; Fitzgerald, Wong & Zucker, 2013; Weatherston & Fitzgerald, 2010). One factor often contributing to this is parent psychopathology (Zucker, 1987). As can be seen from Table 2, the MLS recruitment strategy resulted in a sample of families with different levels of parent psychopathology in the homes in which these young boys were being raised (Zucker et al., 2000). Generally, the parents in the alcoholic families were functioning at lower levels than control families on various psychopathology indicators, with the lowest functioning most often seen in the highest risk families (i.e., those recruited from the courts). This was seen among fathers in terms of their antisocial behavior both as children and adolescents, the life-severity of their depression, their history of lifetime alcohol problems, and their overall low global adaptive functioning. Among mothers, those from court recruited families had lower functioning in these areas as well, although the contrast between those from the community-recruited alcoholic families and control families was not as stark. Although recruitment wasn't based on mother's alcohol problems, other than that mothers in control families could not have substance problems, the fact that mothers’ functioning was also poorer in the alcoholic families indicated assortative mating, or was the result of living with a more damaged partner (Zucker et al., 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, Wong, Fitzgerald, & Zucker, 2006). Such family level indicators add to the ecological risk environment for young children growing up in these homes, in effect creating high levels of ACE.

Table 2.

Parent Psychopathology as Indicators of Family Psychosocial Adaptation during the Early Child Rearing Years among MLS Participants (Boys at Ages 3 - 5)

| Court Recruited | Community Recruited | Controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 158) | (n = 60) | (n = 90) | ||

| Father | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F |

| Psychopathology | ||||

| Beck Depression | 3.04 (3.19) | 2.47 (2.60) | 1.85 (2.11) | 4.95**a |

| Hamilton Depression | 15.54 (10.22) | 13.37 (12.89) | 7.82 (7.11) | 16.32***ac |

| Child Antisociality | 11.69 (7.78) | 8.53 (4.74) | 6.49 (4.51) | 18.32***abc |

| Adult Antisociality | 12.18 (7.97) | 7.71 (4.11) | 5.35 (3.46) | 33.73***abc |

| LAPS | 11.24 (2.00) | 10.19 (1.68) | 7.70 (2.01) | 89.94***abc |

| GAF | 53.64 (10.05) | 63.39 (8.62) | 67.38 (10.27) | 57.33***abc |

| Mother | ||||

| Psychopathology | ||||

| Beck Depression | 3.60 (3.54) | 2.57 (2.22) | 2.97 (3.33) | 2.29*b |

| Hamilton Depression | 17.54 (10.82) | 16.67 (14.27) | 12.95 (10.81) | 4.46*ac |

| Child Antisociality | 8.17 (6.60) | 6.10 (4.17) | 4.65 (3.41) | 11.98***abc |

| Adult Antisociality | 6.56 (4.94) | 4.96 (3.27) | 4.34 (3.71) | 12.09***a |

| LAPS | 10.43 (1.88) | 10.23 (1.30) | 9.11 (1.25) | 8.83***ac |

| GAF | 57.67 (11.28) | 63.35 (7.45) | 66.13 (9.85) | 19.78***ab |

Note: LAPS = Lifetime Alcohol Problem Score GAF = DSM-IV Axis V (Global Adaptive Functioning

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Court > Control

Court > Community

Community > Control

Other environmental stress factors that likely influenced both distal and proximal outcomes for the offspring were also found early on in the MLS families. The alcoholic families had more troubles in job-related, financial, and legal matters, and also were lower in socioeconomic status (Fitzgerald & Zucker, 1995). Negative marital interactions (Floyd, Cranford, Klotz-Daugherty, Fitzgerald, & Zucker, 2006; Cranford, Floyd, Schulenberg, Fitzgerald & Zucker, 2011), father-son conflict (Loukas, Fitzgerald, Zucker, & von Eye, 2001), poorer quality parent-child interactions (Whipple, Fitzgerald, & Zucker, 1995), high family residential mobility (Buu et al., 2007), and neighborhood stress (Buu et al, 2009) also characterized families who were of higher risk for AUD and co-morbid outcomes.

Child Functioning and Early Risk Indicators

Although the family, both in terms of environmental and genetic influences, provides initial risk components for the development of AUDs, even early on child personality, temperament, and behavioral factors are pertinent. Importantly, these are not just the consequences of parental risk, but contribute to risk levels themselves as development ensues over the lifespan. In addition to results from the MLS, in this section we also use results from the Buffalo Longitudinal Study (BLS), which followed a sample of alcoholic and nonalcoholic families beginning when the children were 10 months old (Eiden, Chavez, & Leonard, 1999; Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2002), to help demonstrate other child characteristics which are likely distal factors along the pathways to an eventual AUD outcome. Results from the BLS showed that infants from alcoholic homes generally had more insecure attachments than children from nonalcoholic homes, and in homes where both parents had drinking problems and antisocial behavior and depression, the incidence of disorganized attachment was 30 percent (Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2002).

With regard to children's temperament, both the BLS and MLS showed differences between children reared in an alcoholic environment and children not reared in such situations. BLS results showed that infants of alcoholic fathers were more likely to be impulsive and have difficult temperaments than children of nonalcoholic fathers (Eiden, Chavez, & Leonard, 1999; Fitzgerald & Eiden, 2007). MLS results showed more impulsiveness in young boys of alcoholics and also higher activity, shorter attention spans, and higher reactivity in these boys which later predicted higher levels of externalizing behavior (Fitzgerald & Eiden, 2007; Loukas, Fitzgerald, Zucker, & Von Eye, 2001). In addition, boys with parents with two or more lifetime psychiatric diagnoses, tended to have higher externalizing behavior problems and activity levels, shorter attention spans, and higher reactivity (Mun, Fitzgerald, Von Eye, Puttler & Zucker, 2001). Similarly, in the BLS, boys with alcoholic fathers showed lower levels of effortful control than boys with nonalcoholic fathers (Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2004; Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2007).

In terms of what actual brain mechanisms might be involved that impact the occurrence of this behavior, recent fMRI studies from the MLS suggest that an attenuated deactivation of the left ventral striatum may lead to inappropriate motivational responding and may thus be a pre-existing risk factor of familial risk of alcohol through the externalizing pathway (Heitzeg, Nigg, Yau, Zucker, & Zubieta, 2010), that activation of the nucleus accumbens increased as a function of externalizing problems among children of alcoholics (COAs; Yau et al., 2012), and that maturational trajectories that are inconsistent with normal response inhibition development, particularly in the right hemisphere, may be a contributing factor for subsequent problem substance use (Hardee et al., 2014).

An advantage, as well as a disadvantage, of doing longitudinal research is that the field changes, with new knowledge in the measurement of constructs, the analytic possibilities, and theory, as a function of paradigm shifts. Early MLS analyses, when the children were between the ages of 3-5, mostly used COA status as the primary grouping variable. Focusing on risk in this manner, and consistent with other extant literature, we noted that early findings from the MLS showed significant differences between 3-5 year olds who were COAs and those who were not; the COAs had higher levels of externalizing and internalizing behavior, lower intellectual functioning, and higher levels of difficult temperament (Fitzgerald et al, 1993; Puttler, Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Bingham, 1998).

Although COAs are at higher risk for subsequent problems both as children and adults, not all COAs develop such problems (West & Prinz, 1987). There is a long history of looking at alcoholism as a heterogeneous disorder (Zucker, Heitzeg, & Nigg, 2011). Thus, as the MLS children grew older, analyses of their functioning used groupings based on one of the most common subtypes, antisocial comorbidity with alcoholism. Using fathers’ developmental history of antisocial behavior and their AUD diagnosis as a categorizing variable, MLS families were divided into groups of antisocial alcoholic families (AALs), nonantisocial alcoholic families (NAALs), and controls. Results showed that children aged 3-8 from AAL families had greater levels of behavior problems (both externalizing and internalizing) than did those children from NAAL families and controls (Puttler et al., 1998; Zucker et al., 2000). Boys from AAL families also had higher scores on a hyperactivity index and more risky temperament, and displayed the worst IQ and academic achievement compared with children of nonantisocial alcoholics (NAALs) and controls. In addition, children of AALs displayed relatively poorer abstract planning and attentional capability compared with children from control families (Poon et al., 2000; Zucker et al., 2000). For externalizing behavior, children from NAAL families were at an intermediate risk level; they had greater problems than children from control families, but fewer than children from AAL families (Puttler et al., 1998). For the other outcomes, the risk burden was seen only in the children from AAL families; children from NAAL families were statistically indistinguishable from children from control families. Additionally, even using T-scores normed for gender, overall boys had higher levels of total behavior problems, as well as for externalizing and internalizing behavior, compared to girls (Puttler et al.).

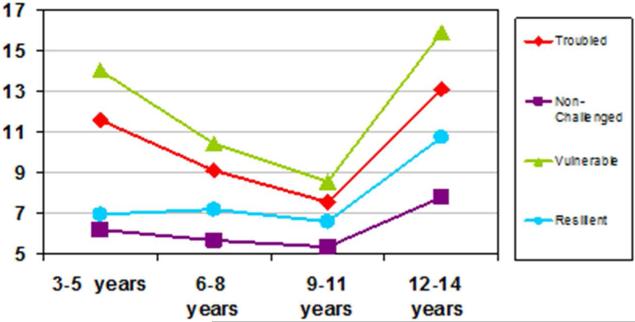

Adding in the child's own early behavioral functioning into the mix of risk for later problems, Zucker, Wong, Fitzgerald, and Puttler (2003) created four groups based on parental risk (presence of AUD and antisociality) and early child behavior problems (above or below the 80th percentile for total behavior problems) when the children were between the ages of 3-5. The four groups of children were labelled as: “Vulnerable” (children with high parental and child adversity, “Resilient” (children with high parent and low child adversity), “Non-Challenged” (children with low parent and low child adversity), and “Troubled” (children with low parent and high child adversity).

Figures 3 and 4 show the results for Externalizing and Internalizing Behavior from early childhood through early adolescence. As can be seen in Figure 3, at all ages the “Vulnerable” group had the most externalizing behavior symptoms followed by the “Troubled”, “Resilient”, and “Non-Challenged” Groups. The pattern also has a normative developmental decrease in such behavior during middle childhood, which then increases again during adolescence (Achenbach, 1991). “Resilient” children are similar to “Non-Challenged” children at early ages, but show an increase in externalizing problems during adolescence bringing them closer to those children with higher adversity early in life.

Figure 3.

Stability and Change in Externalizing Symptoms Through Early Adolescence

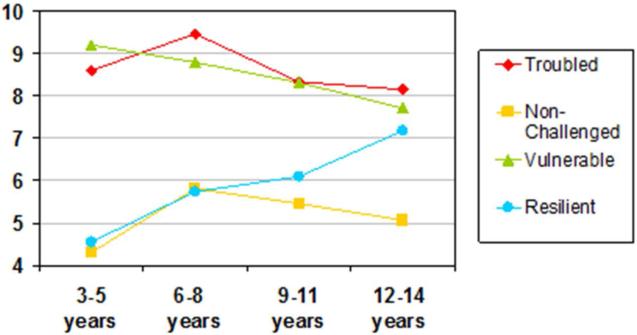

Figure 4.

Stability and Change in Internalizing Symptoms Through Early Adolescence

Figure 4 shows a somewhat differing pattern for internalizing behavior problems. The “Vulnerable” and “Troubled” groups were highest in symptoms while the “Resilient” and “Non-Challenged” were lowest. Interestingly, although relatively low in symptoms again during early childhood and looking like the “Non-Challenged” group, the “Resilient” groups internalizing symptoms increased during adolescence to the point they resembled the higher two risk groups showing how exposure to sustained adversity can lead to a shift from more normative to more troubled behavior (Zucker, Hicks, & Heitzeg, 2016).

With regard to alcohol-specific risk factors in the development of AUD, the initiation of drinking at an early age is now understood to be a common risk factor for a variety of negative outcomes (Dewit, Adlaf, Offord & Ogborne, 2000; Hingson, Heeren, & Winter, 2006). In the MLS, Mayzer and colleagues (2009) showed that higher levels of early externalizing and internalizing behavior were predictive of both early onset on drinking, as well as higher levels of externalizing and internalizing behavior and delinquent activity in adolescence.

Thus far, we have focused on identification of problem behaviors in preschool aged boys; behaviors that are elevated in families that generate high adverse childhood experiences due to alcohol and other drug abuse, co-morbid psychopathology, and marital conflict. We have mirrored the majority of the AUD literature (i.e., focusing on the observable behaviors that often predict transition into problems behaviors of childhood through emergent adulthood). However, behavioral manifestations, along with their underlying neurobiology and neuroendocrinology (see Schore, 2016), are not the only aspects of the organization of risk or its cascade to pathology over the life course. Equally important, though rarely studied in the AUD literature, are the subjective internalized aspects of the intersubjective self that affect personality development.

The Development of Alcohol Expectancies, the Self and and Mental Representations

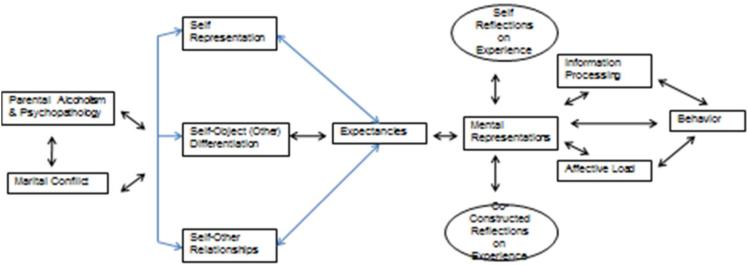

During the years from birth to five, children exposed to high degrees of parent conflict, paternal and maternal psychopathology, and poor family and neighborhood resources are more likely to develop pathological mental representations of self, other, and self-other relationships than are children who are not exposed to such rearing environments (Gaensbauer, 2016). There is strong evidence that during the preschool years, children begin to form working models, schemas, or autobiographical memories about familiar events (Karlen, 1996; Mennella & Garcia, 2000; Schneider & Bjorklund, 1998). In most instances, these memories are positive and provide the basis for normative developmental pathways to adulthood. But this is not always the case. Gaensbauer (2016) notes that “Children's needs to recreate unhealthy, but affectively meaningful, moments with their caregivers can lead to ingrained, automatically operating pathological patterns of social behavior and affective expression that can take on a life of their own and strongly shape the child's subsequent socioemotional functioning.” (p 172). Underlying the organization of such negative “automatically operating pathological patterns”, are core issues related to the development of the self and the meaning-making that occurs during self-other relationships that become internalized as mental representations. Few studies of children at high risk for AUD attempt to ascertain how mental representations are organized, and how they scaffold into more complex representations primarily by incorporating social-emotional or affective aspects of development. The field also has not spent much time assessing how exposure to highly adverse rearing environments affects the organization of such representations or the neural networks that mediate connectivity between such neural structures and behavior (Fitzgerald, Puttler, Mun & Zucker, 2000; Fitzgerald & Zucker, 2000). That said, as a way to help the reader understand what follows, Figure 5 shows a heuristic model of how early mental representations in the context of parental psychopathology and marital conflict may unconsciously impact the behavior of the developing child with respect to the etiology of AUD and co-morbid psychopathology (Fitzgerald, Wong, & Zucker, 2013). This model is an expansion of our original model (Fitzgerald & Zucker, 2000; Fitzgerald et al., 2000).

Figure 5.

Mental Representations and Priming for Alcoholism and Co-Active Psychopathology

Self and mental representations: The study of the development of the self draws upon numerous concepts (empathy, meaning-making, mind reading, mental and representational models). In addition, it is guided by an equally broad set of theories (simulation theory, embodied simulation theory, theory of mind, theory-theory, interaction theory, and systems theory) (Fitzgerald et al., 2013; Ammaniti & Gallese, 2014). The infant enters the world, in essence, not knowing anything in the sense of conscious awareness of self (Trevarthan, 1980). While infants might not “know” anything at birth, they are biologically prepared to quickly learn. By the preschool years child can converse, think, solve problems, manipulate objects, show affection, tease, recall and verbalize experiences, and otherwise, relate to others in ways not imaginable from observation of the newborn's functional abilities. This rapid transition starts with the development of a self, which fuels self-other differentiation, self-awareness, and the emergence of self-other relationships. This developmental transition is facilitated, in part, by the development of mental representations of the events and relationships that form during the first five years.

Mental representations, or schemas, involve the encoding of experiences into long-term memory. They begin very early in life, but are influenced by rehearsal and reminders from adults (Fitzgerald & Zucker, 2006), as well as observation (Ammaniti & Gallese, 2014, Howe & Courage, 1997). In terms of alcohol, findings from the MLS suggest that as early as preschool age, children are developing mental models or schema that include context, motivation, affect, and norms about alcohol use (Zucker & Fitzgerald, 1991; Zucker, Kincaid, Fitzgerald, & Bingham, 1995). These schemas are based primarily on child sensory and perceptual experiences related to their exposure to the use of alcohol beverages in the home, the individuals who are using them, and the contexts of their use. Within that frame, we found that sons of male alcoholics are more able to identify specific alcoholic beverages, to identify a greater number of alcoholic beverages, and to demonstrate the contextual understanding that often the role of father includes drinking as part of the role (Zucker et al., 1995).

As development continues, both positive and negative expectancies for alcohol use are also created. Over the years, these expectancies can have a strong impact on adolescent alcohol involvement in other studies, even after controlling for other variables (Goldman, Del Boca, & Darkes, 1999). In the MLS sample, adolescent boys’ negative and positive alcohol expectancies were longitudinally associated with higher odds of any intoxication three years later, and positive alcohol expectancies further predicted frequency of drunkenness, independently of parental alcohol involvement (Cranford, Zucker, Jester, Fitzgerald, & Puttler, 2010).

Self and intersubjectivity. Observations of events are only part of the mental representations that are aspects of the emergent self. Over 100 years ago, William James (1890) drew attention to two aspects of the self, the empirical self (me) and the existential self (I). Lewis and Brooks-Gunn (1979) expanded on James’ views with their distinction between the categorical self (empirical, what am I), and the subjective (existential, who am I) self. Categorical features of the self are anchored to external contexts, observable events; those characteristics that give observable definition to what I am such as gender, height, skin color, eye color, physical activity, a COA, etc. These are the group memberships one can identify based upon both self and other observations. Thus, I am a boy because I look like my father, and others affirm that I am a boy. They are linked to sensory-motor and perceptual experiences related to observable events. The alcohol schema we described previously is directly related to the alcohol smells and containers present in the child's home, to the individuals who use them, and to their behavior as a result of use. On the other hand, subjective features of the self are internalized, and relate to who I am. They are the narratives of shared experience that parents construct and become the scripts or knowledge structures (conscious and unconscious) that children use to create their initial autobiographical memories. The subjective facet of the self is phenomenological, formed via intersubjective relationships, and the meaning making that flows from language and communication with caregivers and others.

Intersubjectivity refers to the development of shared meaning between the self and others. It is an aspect of procedural or unconscious knowledge that underlies that gives rise to the development of the moral self during infancy and early childhood (Emde, Birigen, Clyman & Oppenheim, 1991). While the processes involved in developing procedural knowledge of rules may be biologically based, as Emde et al. contend, the content of what is and is not moral behavior is not. It emerges from self-other interactions, which during infancy are intensely affective, mother-infant centered, and involve the social construction of meaning about what is right and wrong and who is right or wrong. In the context of children reared in highly adverse environments, including alcoholic families with high co-morbid psychopathology, it is important to note findings such as those reported by Radke-Yarrow, Belmont, Nottelmann, and Bottomly (1990) that “children's self-references are consistent with an interpretation that mothers’ negatively toned comments influence children's negative-self references (p 359).” In addition, children who are maltreated not only have poor attachment relationships with their mothers, but also have poorly internalized mental models of relationships and self (Cicchetti, Beeghley, Carlson, & Toth, 1990).

Emde's procedural rules (unconscious representations) are what Bürgin (2011) refers to as “intrapsychic entities” which give symbolic meaning to observed events and which are unconsciously evoked during subsequent self-other interactions. Fraiberg, Adelson and Shapiro's (1975) concept of “ghosts in the nursey” metaphorically refers to the intrapsychic entities or procedural rules generated during a mother's own upbringing; rules or memories that interfere with her ability to form positive nurturing relationships with her own infant. Barrows (1994) views fathers’ ghosts primarily within the context of the father-mother relationship, and notes that in the final analysis it is the father-mother relationship that plays a key role in shaping the child's intersubjectivity. What “ghosts in the nursery” are acquired by infant and toddler COAs that interfere not only with their relationships with others, but with their own reflective awareness of self? The work by Mennella and Beauchamp (1998), showing that infants nursing with mothers who drink are more likely to choose toys scented with the smell of alcohol, provides one concrete example of the very early beginnings of an awareness of self and others, that in this instance includes alcohol in actively alcoholic families. Thus, a toy smelling of alcohol (sensory-perceptual schema about objects) is preferred because it is not only recognized via the senses, but may also be consistent with the child's emergent awareness of the existential I.

Stern (1985) asserts that intersubjective relatedness organizes during the 7th to 15th postnatal months of life, and includes the time when infants become aware that they have a mind, and that others do as well. The infant becomes consciously aware that inner subjective experiences can be shared through inter-attentionality (joint attention), inter-affectivity (affect attunement), and inter-intentionality (mutual sharing of intention and motives). It is the same time when infants begin to organize self-regulation and self-other relationships within the context of contingencies between self and others that brings procedural knowledge of self-other relationship to conscious awareness (Trevarthen, 1980). Thus, it is interesting to note that in the BLS, 30 percent of the infants exposed to dual parent psychopathology were classified as having disorganized attachment relationships (Eiden, Edwards & Leonard, 2002). So it is not surprising that very young children of alcoholic fathers were also more likely to have difficult temperaments, negative moods, and problems with impulsivity than were the infants and toddlers of non-alcoholic fathers, as was also the case for MLS children both when they were preschool age (Fitzgerald et al., 1993) and older (Loukas, Fitzgerald, Zucker & von Eye, 2001). Thus, there is increasing synchrony between the child's behavior and feedback systems that strengthen the child's intersubjective sense of self, and not always with a positive outcome.

Contemporary neuroscientists and philosophers link the categorical and subjective aspects of self to the specialization of the left and right hemispheres of the brain (McGilchirst, 2016, Schore, 2001; 2016), and the neural networks that organize and integrate social, emotional, and cognitive aspects of self and self-other relationships. The left hemisphere (LH) mediated self is viewed as categorical. It is objective, external, certain, and event- or action-oriented. It involves left motor cortex, speech centers, and logic. The right hemisphere (RH) mediated self, in contrast, is social, empathic, dynamic, uncertain, relationship-oriented. It involves the right frontal and right cingulate cortex. As McGilchrist (2016) characterizes it, “The RH, with its understanding of possibility, change, and flow, is far better than the LH at incorporating new information into a schema, without having necessarily to abandon it, while the LH, with its attachment to the fixed and certain, sticks stubbornly to what I ‘knows’ at all costs, in the teeth of evidence to the contrary.” (pps. 205-206). The schema we described for COAs in the MLS is perceptual, sensory, event-based, concrete, and left hemisphere oriented. Ammaniti and Gallese (2014) posit that intersubjectivity has its origins in sensory-motor processing of events that get coded by mirror neurons and become scaffolded into complex social-emotional and cognitive relationship dynamics. Scaffolding, largely a right hemisphere mediated process, affects the organization of the self, self-object differentiation, attachment relationships, and the emergence of cognitive representational memories, in part, from meaning making conversations with parents and significant others.

As mentioned above, the literature on mental representations encompasses concepts of meaning-making, mind-reading, mental and representational models while embracing simulation theory, embodied simulation theory, theory of mind, theory-theory, interactive theory, and systems theory (Ammaniti & Gallese, 2014; Bowby, 1969; Carruthers, 2013; Goldman, 2006; Howe & Courage, 1997; Sameroff, 2000; Tronick & Beeghly, 2011). The key parameter cutting across all of these literatures and theoretical approaches is that through the process of parent-child relationship development, parents play a key role in constructing current, past, and future experiences (meaning making), whereas, children simultaneously organize their memories of lived experiences, and subsequent self-referenced understandings of meaning both categorically and existentially. The dynamic interpersonal relationship experiences of infancy and early childhood contribute to the very young child's understanding of both the objective and subjective aspects of self, others, and self-other relationships (Fitzgerald et al., 2013), and we posit that they also create mental representations that guide choice behaviors later in childhood with respect to peer selection, drinking and smoking onset, and antisocial and relationship-based behaviors (see Figure 5).

Interestingly, many studies document the relationship between early relationship disorders (right hemisphere mediated) and early exposure to trauma, and children's narratives. Such narratives often take the form of behavior that may originate from mirror neurons located in the brain's ventral premotor cortex, inferior parietal lobe, or the inferior frontal gyrus (Fox et al., 2016). For example, analyses from the MLS indicate that preschool age children who are exposed to parental use of aggression and conflict display high levels of aggression, externalizing and antisocial behavior (Muller, Fitzgerald, Sullivan & Zucker, 1994). It would be easy to attribute these behavioral parallels between sons and their fathers to the domain of the categorical self (Caruthers, 2013), but there is deeper explanation as well, one that may prime the very young child to integrate the categorical self (fathers observed acts of aggression) with the right hemisphere mediated subjective or existential self. Is it possible that during the earliest years of development, children exposed to very high ACEs embody far more into their emergent sense of self than the simple observed actions of adults in their environments? Children's observations of parental conflict and violence within the context of drinking provide opportunities to code such dynamics into procedural or non-declarative memory, or what we refer to as scrips or mental representations. Clearly such events lead to high rates of disorganized attachment (Zeanah et al., 1999) and fear in very young children (Main & Hesse, 1990). Figure 5 shows a visual representation of how early experiences may maintain, increase, or decrease cumulative risk affecting the organization of the self, priming the toddler to embark on a pathway of normative development, or one that leads to the organization and eventual expression of psychopathology, including AUD, antisocial behavior, and poor interpersonal relationships. Our model suggests that parents, particularly mothers during infancy and toddlerhood (Fitzgerald, Zucker, Maguin & Reider, 1994), play a critical role in helping their children construct meaning with their experiences, layering relational meaning onto observed acts that are encoded into neurobiological networks that mediate mental representations and contribute to the development of the child's subjective self, an unconscious awareness of the I.

Continuity and Discontinuity Pathways Toward Development of AUD

One way to sum up the information provided in this article is to emphasize the importance of understanding the continuity and discontinuity of risk over the developmental span. A potential continuity pathway involves the early emergence of problems that are sustained by familial, neighborhood, and peer influences that impact biobehavioral dysregulation over time (Fitzgerald & Eiden, 2007). The early problems include difficult temperament, insecure attachment, poor self-regulation, externalizing behavior, and lower cognitive abilities that emerge before or during the elementary school years, then often transition into substance use, sexual behavior, poor school performance, and involvement with the criminal justice system during adolescence. Often, these problems continue when the individuals become adults in even more severe forms. This pathway is hypothesized to be more common among families with alcoholism and other comorbidities such as the AALs described previously.

Fitzgerald and Eiden (2007) also suggest two potential discontinuity pathways that show more individual differences and greater diversity in both risk and protective factors. During early years, these children show little signs of problems or the impact of risk, but stressors such as family disorganization, conflict, parent marital problems, and peer group influences impact the push away from more normative development to more risky behavior during adolescence. The two proposed pathways diverge in that one involves the expression of both internalizing and externalizing behavior, while the other involves mostly externalizing behavior. The discontinuity pathways are proposed to be more common in NAAL families and those in which the mother is relatively free of psychopathology (Fitzgerald & Eiden). Regardless of pathway variation, it is clear that in research with children, little attention is given to the subjective or intersubjective experiences of the child with respect to their internalization of lived experiences apropos of etiologic contributions to AUD and co-morbid psychopathology.

We now know a great deal about the development of AUDs from research done over the past few decades. This disorder is developmental in its nature and places children, and boys in particular, at risk for many problems if the pathways to the disorder are not interrupted. Fortunately, research is having an impact on the creation of new prevention and intervention programs. Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide details of this work here, the reader is referred to a very recent publication from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (2016) as one example for further discussion of such programs.

Acknowledgements

This research is currently being supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA07065, R01 AA12217) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA039112), with previous support also from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA027261)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. The authors have no conflicts.

References

- Achenbach T. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ammaniti M, Gallese V. The birth of intersubjectivity: Psychodynamics, neurobiology and the self. W. W. Norton; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barrows P. Fathers and families: Locating the ghost in the nursery. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004;25:408–423. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol.1: Attachment. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bürgin D. From outside to inside to outside: Comments on intrapsychic representations and interpersonal interactions. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2011;32:94–114. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buu A, Mansour MA, Wang J, Refior SK, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Alcoholism effects on social migration over the course of 12 years. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buu A, DiPiazza C, Wang J, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Parent, family and neighborhood effects on the development of child substance use and other psychopathology from preschool to the start of adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:489–498. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers P. Mindreading in infancy. Mind & Language. 2013;28:141–172. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Rogosch F, Barrera M. Substance use and symptomatology among adolescent children of alcoholics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):449–463. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Beeghly M, Carlson V, Toth SL. The emergence of the self in atypical populations. In: Cicchetti D, Beeghly M, editors. The self in transition: Infancy to childhood. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1990. pp. 309–344. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group School outcomes of aggressive disruptive children: Prediction from kindergarten risk factors and impact of the Fast Track prevention program. Aggressive Behavior. 2013;39:114–130. doi: 10.1002/ab.21467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Zucker RA, Jester JM, Fitzgerald HE, Puttler LI. Parental alcohol involvement and adolescent alcohol expectancies predict alcohol involvement in male adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(3):386–396. doi: 10.1037/a0019801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Floyd FJ, Schulenberg JE, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RE. Husbands’ and wives’ alcohol use disorders and marital interactions as longitudinal predictors of marital adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:210–222. doi: 10.1037/a0021349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: A risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Leech SL, Zucker RA, Loveland-Cherry CJ, Jester JM, Fitzgerald HE, Looman WS. Really underage drinkers: Alcohol use among elementary students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(2):341–349. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000113922.77569.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Chavez F, Edwards EP. Parent-infant interactions among families with alcoholic fathers. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11(4):745–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. Mother-infant and father-infant attachment among alcoholic families. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14(2):253–276. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. Predictors of effortful control among children of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fathers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(3):309–319. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. A conceptual model for the development of externalizing behavior problems among kindergarten children of alcoholic families: Role of parenting and children's self-regulation. Development Psychology. 2007;43(5):1187–1201. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis DA, Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE. Children of alcoholics: The role of family influences on development and risk. Alcohol, Health & Research World. 1997;21:218–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Biringen Z, Clyman RB, Oppenheim D. The moral self of infancy: Affective core and procedural knowledge. Developmental Review. 1991;11:251–270. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Eiden RD. Paternal alcoholism, family functioning, and infant mental health. Journal of ZERO TO THREE. 2007;27:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Puttler LI, Mun E-Y, Zucker RA. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to parental alcohol use and abuse. In: Osofsky JD, Fitzgerald HE, editors. WAIMH Handbook of Infant Mental Health (Vol 4): Infant mental health in groups at high risk. Wiley; New York: 2000. pp. 123–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Puttler LI, Refior S, Zucker RA. Family responses to children and alcohol. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly: Families and Alcoholism. 2007;25:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Sullivan LA, Ham HP, Zucker RA, Bruckel S, Schneider AM, Noll RB. Predictors of behavioral problems in three-year-old sons of alcoholics: Early evidence for the onset of risk. Child Development. 1993;64(1):110–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Wong MM, Zucker RA. Early origins of alcohol use and abuse: Mental representations, relationships, and the challenge of assessing the risk-resilience continuum very early in the life of the child. In: Suchman NE, Pajulo M, Mayes LC, editors. Parenting and substance abuse: Developmental approaches to intervention. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2013. pp. 126–155. Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Socioeconomic status and alcoholism: The contextual structure of developmental pathways to addiction. In: Fitzgerald HE, Lester BM, Zuckerman B, editors. Children of poverty: Research, health, and policy issues. Garland Press; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 125–148. Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Effets á court et á long terme de l’alcoolism parental sure les enfants (Short and long terms effects of parental alcohol use on children). PRISME. 2000;33:28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Pathways of risk aggregation for alcohol use disorders. In: Freeark K, Davidson WS III, editors. The crisis in youth mental health: Vol 3, Issues for families, schools, and communities. Praeger Press; Westport, CT: 2006. pp. 249–271. Chapter 11. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA, Maguin ET, Reider EE. Time spent with child and parental agreement about ratings of child behavior. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1994;79:336–338. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.79.1.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA, Puttler LI, Caplan HM, Mun E-Y. Alcohol abuse/dependence in women and girls: Etiology, course, and subtype variations. Alcoscope: International Review of Alcoholism Management. 2000;3(1):6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Cranford JA, Klotz-Daugherty M, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Marital interaction in alcoholic and nonalcoholic couples: Alcoholic subtype variations and wives’ alcoholism status. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(1):121–130. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Lynton P, Strathern L. Borderline personality disorder, mentalization, and the neurobiology of attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2011;32:47–69. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Yoo KH, Bowman LC, Cannon EN, Vanderwert RE, Van IJzendoorn MH. Assessing human mirror activity with EEG Mu rhythm: A meta analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2016;142:291–313. doi: 10.1037/bul0000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraiberg S, Adelson E, Shapiro V. Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1975;14:387–421. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaensbauer TJ. Moments of meeting: The relevance of Lou Sander's and Dan Stern's conceptual framework for understanding the development of pathological social relatedness. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2016;37:172–188. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman AI. Simulating Minds. Alfred A. Knopf; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Del Boca FK, Darkes J. Alcohol expectancy theory: The application of cognitive neuroscience. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd ed. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 203–246. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Chu A, Sigman R, Amsbary M, Kali J, Sugawara Y, Goldstein R. Source and Accuracy Statement: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM–IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Alcohol Research & Health. 2006;29(2):79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Hasin DS. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. Journal of the American Medical Academy Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardee JE, Weiland BJ, Nichols TE, Welsh RC, Soules ME, Steinberg DB, Heitzeg MM. Development of impulse control circuitry in children of alcoholics. Biological Psychiatry. 2014;76(9):708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzeg MM, Nigg JT, Yau WY, Zucker RA, Zubieta JK. Striatal dysfunction marks preexisting risk and medial prefrontal dysfunction is related to problem drinking in children of alcoholics. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(3):287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe ML, Courage ML. The emergence and early development of autobiographical memory. Psychological Review. 1997;104(3):499–523. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Wirth RJ, Edwards MC, Curran PJ, Chassin LA, Zucker RA. Externalizing symptoms among children of alcoholic parents: Entry points for an antisocial pathway to alcoholism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(3):529–542. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W. The principles of psychology. Henry Holt & Company; New York: 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Karlen L. Attachment relationships among children with aggressive behavior problems: The role of disorganized early attachment patterns. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:64–73. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Brooks-Gunn J. Social cognition and the acquisition of self. Plenum Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA, Von Eye A. Alcohol problems and antisocial behavior: Relations to externalizing problems among young sons. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29(2):91–106. doi: 10.1023/a:1005281011838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Hesse E. Parents' unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In: Greenberg M, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research and intervention. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1990. pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mayzer R, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Anticipating problem drinking risk from preschoolers’ antisocial behavior: Evidence for a common delinquency-related diathesis model. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(8):820–827. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181aa0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGilchrist I. ‘Selving’ and union. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 2016;23:196–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mennella JA, Beauchamp GK. The infant' s response to scented toys: effects of exposure. Chemical Senses. 1998;23:11–17. doi: 10.1093/chemse/23.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennella JA, Garcia PL. Children's hedonic response to the smell of alcohol: effects of parental drinking habits. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1167–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex differences in antisocial behavior, conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin longitudinal study. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Muller RT, Fitzgerald HE, Sullivan LA, Zucker RA. Social supportr and stress factors in child maltreatment among alcoholic families. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 1994;26:438–461. [Google Scholar]

- Mun EY, Fitzgerald HE, von Eye A, Puttler LI, Zucker RA. Temperamental characteristics as predictors of externalizing and internalizing behavior problems in the contexts of high and low parental psychopathology. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:393–415. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse [March 14, 2016];A child's first eight years critical for substance abuse prevention. 2016 from https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/news-releases/2016/03/childs-first-eight-years-critical-substance-abuse-prevention.

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24(8):981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wong MM, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Depressive symptoms over time in women partners of men with and without alcohol problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(3):601–9. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon E, Ellis DA, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Cognitive functioning of sons of alcoholics during the early elementary years: Differences related to subtypes of familial alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24(7):1020–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puttler LI, Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Bingham CR. Behavioral outcomes among children of alcoholics during the early and middle childhood years: Familial subtype variations. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22(9):1962–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke-Yarrow M, Belmont B, Nottelmann, Bottomly L. Young children's self-conceptions: Origins in the national discourse of depressed and normal mothers and their children. In: Cicchetti D, Beegley M, editors. The self in transition: infancy to childhood. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1990. pp. 345–361. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Developmental systems and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:297–312. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Bjorklund DF. Memory. In: Khun D, Siegler RS, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 2. Cognition, perception, and language. Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 467–521. [Google Scholar]

- Schore AN. The effects of secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:7–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schore AN. All our sons: The developmental neurobiology and neuroendocrinology of boys at risk. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2016;37:00–000. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliam M. Early childhood predictors of low-income boys’ antisocial behavior. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2016;37:00–000. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(4):819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson E, Collins WA. The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stern D. The interpersonal world of the infant: A view from psychoanalysis and developmental psychology. Basic Books; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen C. The foundations of intersubjectivity: Development of interpersonal and cooperative understanding in infants. In: Olson D, editor. The social foundations of language and thought. W. W. Norton; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Tronick E, Beeghly M. Infants meaning making and the development of mental health problems. American Psychologist. 2011;66:107–119. doi: 10.1037/a0021631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherston D, Fitzgerald HE. Role of parenting in the development of the infant's interpersonal abilities. In: Tyano S, Keren M, Herman H, Cox J, editors. Parenthood and mental health: A bridge between infant and adult psychiatry. Wiley; New York: 2010. pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- West MO, Prinz RJ. Parental alcoholism and childhood psychopathology. Psycho1ogical Bulletin. 1987;102(2):204–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipple EE, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Parent-child interactions in alcoholic and nonalcoholic families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65(1):153–159. doi: 10.1037/h0079593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Global Status Report on noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yau WY, Zubieta JK, Weiland BJ, Samudra PG, Zucker RA, Heitzeg MM. Nucleus accumbens response to incentive stimuli anticipation in children of alcoholics: relationships with precursive behavioral risk and lifetime alcohol use. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(7):2544–2551. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1390-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Danis B, Hirshberg L, Benoit D, Miller D, Heller SS. Disorganized attachment associated with partner violence: A research note. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1999;20:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. The four alcoholisms: A developmental account of the etiologic process. In: Rivers PC, editor. Alcohol and addictive behaviors; 34th Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1986. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 1987. pp. 27–83. Chapter 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Genes, brain, behavior and context: The developmental matrix of addictive behavior. In: Stoltenberg SF, editor. Genes and the motivation to use substances; Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Vol. 61. Springer; New York: 2014. pp. 51–69. Chapter 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE. Early developmental factors and risk for alcohol problems. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1991;15:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Refior S, Puttler LI, Pallas DM, Ellis DA. The clinical and social ecology of childhood for children of alcoholics: Description of a study and implications for a differentiated social policy. In: Fitzgerald HE, Lester BM, Zuckerman BS, editors. Children of addiction: Research, health, and policy issues. Routledge Falmer; New York, NY: 2000. pp. 109–141. Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Heitzeg MM, Nigg JT. Parsing the undercontrol-disinhibition pathway to substance use disorders: A multilevel developmental problem. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5(4):248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Hicks BM, Heitzeg MM. Alcohol use and the alcohol use disorders over the life course: A cross-level developmental review. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental Psychopathology: Volume 3, Maladaptation and Psychopathology. 3rd Edition. Wiley; New York: 2016. pp. 793–832. Chapter 18. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Kincaid SB, Fitzgerald HE, Bingham CR. Alcohol schema acquisition in preschoolers: Differences between children of alcoholics and children of nonalcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19(4):1011–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Wong MM, Clark DB, Leonard KE, Schulenberg JE, Cornelius, Puttler LI. Predicting risky drinking outcomes longitudinally: What kind of advance notice can we get? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(2):243–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Wong MM, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE. Resilience and vulnerability among sons of alcoholics: Relationship to developmental outcomes between early childhood and adolescence. In: Luthar S, editor. Resilience and Vulnerability: Adaptation in the Context of Childhood Adversities. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. pp. 76–103. [Google Scholar]