Abstract

A 49-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the dermatology clinic for follow-up of malignant melanoma with a complaint of painless gross hematuria. Two years prior she was diagnosed with malignant melanoma from a skin lesion on her left flank treated with wide excision, negative axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy, and adjuvant radiotherapy. Subsequently, she had no evidence of disease until urologic evaluation of her hematuria revealed two lesions in her bladder and cytopathology demonstrated findings consistent with malignant melanoma. We review literature on melanoma metastatic to the bladder and discuss the potential role of metastasectomy and other treatment strategies in such rare cases.

Keywords: Bladder, Melanoma, Cystectomy, Metastatic

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TURBT, transurethral resection of bladder tumor; TUR, transurethral resection; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy

Introduction

While melanoma represents the deadliest form of skin cancer, reported cases of metastasis to the bladder are rare, with just 29 confirmed cases reported in English-language literature. This number is likely an underestimation of the true burden of disease, as autopsy series of patients with metastatic melanoma have found an 18%–37% rate of metastatic disease to the bladder.1, 2 Nonetheless, metastatic disease that presents in the bladder is rare and poses a significant challenge in diagnosis and management. We report a case that highlights such challenges and review literature on metastatic melanoma with a focus on bladder metastases.

Case presentation

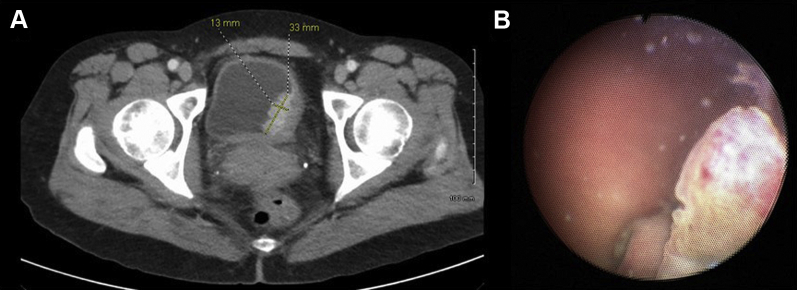

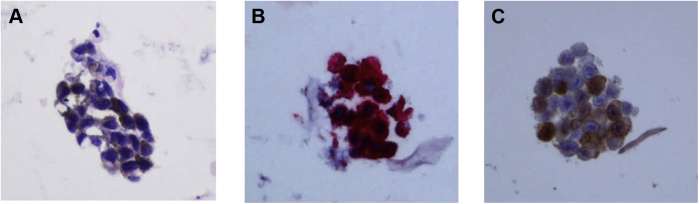

A 49-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the dermatology clinic for follow-up of her malignant melanoma with a complaint of painless gross hematuria. Two years prior she was diagnosed with malignant melanoma from a skin lesion on her left flank. She had a wide excision with negative margins and a negative axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy. The pathology confirmed stage IIC (7 mm thickness, Clark level IV) malignant melanoma and she received 3000 cGy of adjuvant radiotherapy to the left flank. The patient had no evidence of disease until her presentation with hematuria. A computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated two enhancing lesions in the bladder, with the largest one measuring 33 mm in largest diameter along the left posterolateral bladder wall (Fig. 1A). Voided urine cytology identified cells that expressed S-100, HMB-45, and Melan-A, consistent with malignant melanoma (Fig. 2). Cystoscopy demonstrated a large nodular mass with brown pigmentation on the left trigone as well as multiple discontinuous nodular lesions on the left lateral wall (Fig. 1B). Although the remainder of her abdominal/pelvic CT was free of visible disease, a more thorough metastatic survey was completed, and brain magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated frontal and occipital lobe lesions consistent with metastatic disease. Given the multiple sites of metastatic disease, we felt the patient was not likely to derive a survival benefit from metastasectomy, which for complete resection in the location of her trigone would likely require cystectomy. She was treated conservatively with stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) of the brain metastases, systemic therapy with checkpoint inhibitor combination therapy of nivolumab and ipilimumab, and cystoscopic intervention planned for episodes of intractable hematuria.

Figure 1.

Panel A. Axial section CT abdomen/pelvis with IV and oral contrast demonstrating a left posterolateral bladder wall-enhancing lesion measuring 33 mm in largest diameter. Panel B. Cystoscopy reveals large nodular mass (∼3 cm) with brown pigmentation at left posterolateral wall of bladder as well as satellite lesions.

Figure 2.

Cytologic assessment of voided urine demonstrating malignant melanoma diagnosis. Panel A. Malignant cells with fine, brown melanin pigment (H&E stain, ×400). Panel B. Immunohistochemical stain positive for HMB-45 (red chromogen, ×400). Panel C. Immunohistochemical stain positive for S-100 (brown chromogen, ×400).

Discussion

Malignant melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer in the United States with over 67,000 new cases per year and an estimated 30% will eventually develop metastases.3 While the majority of metastatic spread occurs to skin, lungs, liver, and brain, metastasis to the bladder in clinical series appear to be rare with only 29 reported cases in the literature (Table 1). This in contrast to autopsy series which indicate an 18%–37% incidence of metastatic disease in the bladder.1, 2 The most common presenting symptom is hematuria, and isolated metastatic disease to the bladder is relatively rare. The confirmation of metastatic melanoma is made possible through immunohistochemical analysis demonstrating characteristic expression of S-100, HMB-45, MART-1/Melan-A, tyrosinase, and MITF.

Table 1.

Review of English-language literature of metastatic melanoma to the bladder.

| Authors, Journal (year), Pubmed ID | Age and gender | Presenting symptom | Synchronous metastasis | Treatment | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amar, Journal of Urology (1964), 14213534 | 33yo Male | Hematuria | Maxillary lesions | Partial cystectomy | NR |

| Bartone, Journal of Urology, (1964), 14118110 | 70yo Female | Hematuria | Lymph nodes | Partial cystectomy | Died within 2 months |

| Weston and Smith, British Journal of Surgery, (1964), 14103391 | 69yo Male | Urinary retention | Widespread | None | Died 5 days after diagnosis |

| Dasgupta and Grabstald, Journal of Urology (1965), 14290417 | 2 patients A. 35yo Male B. 35yo Female |

A. Hematuria B. Hematuria |

A. Axillary lesion B. Inguinal nodes |

A. Transurethral fulguration B. Tumor cryotherapy and partial cystectomy |

A. Died within 4 months B. NR |

| Meyer, Cancer (1974), 4426038 | 3 patients A. 69yo Male B. 60yo Female C. 42yo Male |

A. Incidental B. Hematuria C. Incidental |

A. Widespread B. Unknown C. Lungs |

A. Chemotherapy B. Partial cystectomy C. TUR |

A. NR B. Died 16 months after resection C. Died 2 months after resection |

| Silverstein et al, JAMA (1974), 4408302 | 56yo Male | Hematuria | Lymph nodes | Intratumor injection of BCG vaccine followed by partial cystectomy | Alive at 8 month follow-up |

| Tolley et al, British Journal of Clinical Practice (1975), 1191491 | 48yo Female | Hematuria | Absent | Radical cystectomy | NR |

| Chin et al, Journal of Urology (1982), 7062434 | 70yo Female | Hematuria, voiding, symptoms, suprapubic pain, fatigue | Bowel | Partial cystectomy Colectomy |

NR |

| Stein and Kendall, Journal of Urology (1984), 6387180 | 50yo Male | Hematuria | Absent | TUR chemotherapy | Alive at 2 year follow-up |

| Arapantoni-Dadioti et al, European Journal of Surgical Oncology (1995), 7851567 | 28yo Female | Dysuria | Brain Lungs Lymph nodes |

Incomplete TUR | 2 months after resection |

| Ergen at al, International Journal of Urology & Nephrology (1995), 8775037 | 65yo Male | Hematuria Flank pain |

Renal pelvis Stomach |

Biopsy | Died within 1 week |

| Demiksesen et al, Urologia Internationalis (2000), 10810279 | 45yo Female | Hematuria, urinary frequency | Widespread | TUR chemotherapy | NR |

| Lee et al, Urology (2003), 12893353 | 46yo Male | Hematuria | Widespread | TUR and high-dose IL-2 immunotherapy | NR |

| Martinez-Giron, Cytopathology (2008), 18713248 | 49yo Male | Hematuria | NR | NR | NR |

| Efesoy and Cayan, Medical Oncology (2011), 21042956 | 60yo Female | Hematuria weight loss | Lungs | TUR | Died 7 months after resection |

| Nair et al, Journal of Clinical Oncology (2011), 21189399 | 54yo Male | Hematuria | Widespread including ureteral and renal pelvic tumors | TUR and laser ablation of ureteral and renal pelvic tumors Chemotherapy |

Died within 3 months of TURBT |

| Charfi et al, Case Reports Pathology (2012), 23133774 | 54yo Male | Unknown | Lymph nodes | TUR | Died within 1 month |

| Paterson et al, Central European Journal of Urology (2012), 24578971 | 84yo Male | Incidental | No other metastatic lesions | None | NR |

| Wisenbaugh et al, Current Urology (2012), 24917713 | 4 patients A. 81yo Male B. 84yo Male C. 85yo Male D. 62yo Female |

A. Hematuria and voiding symptoms B. Incidental C. Hematuria D. Incidental |

A. Solidary B. Small bowel C. Widespread D. Lymph node small bowel widespread |

A. TUR B. TUR C. TUR D. TUR |

A. Alive at 10 months B. Died at 4 months C. Died within 4 months D. Died within 5 months |

| Rishi et al, International Journal of Surgical Pathology (2014), 23794493 | 61yo Female | Hematuria dysuria |

Brain Lung Skin |

TUR Brain radiotherapy High-dose interferon Temozolomide |

Died with 2 months |

| Meunier et al, Case Reports Pathology (2015), 26106499 | 55yo Female | Hematuria | Liver Spleen Lung |

Checkpoint inhibitor | NR |

| Shukla et al, Journal Endourology Case Reports (2016), 27579421 | 60yo Male | Hematuria | Widespread | TUR | Alive at 1 year follow-up |

| Current report | 49yo Female | Hematuria | Brain | Brain SBRT, checkpoint inhibitors | - |

TUR–transurethral resection; SBRT–stereotactic body radiotherapy; NR–not reported.

Once metastatic, treatment options are limited and survival is generally poor, reflecting a lack of effective systemic therapies. Chemotherapeutics have limited effect on survival, however the introduction of immunotherapy has been promising in select cases. Interleukin-2 therapy was introduced in the late 1990s but with a low response rate and significant side effects including an inflammatory response syndrome that often limits treatment. Targeted therapies in the form of BRAF, MEK, KIT, VEGF pathway inhibitors have improved response rates, but not durably. More recent use of checkpoint inhibitors including antibodies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 and CTLA4 are promising due to higher response rates and a chance of durable response.4

Location of the initial metastatic site appears to be a significant predictor of survival with improved survival for skin metastases, and progressively lower survival associated with distant nodal involvement, gastrointestinal, lung, bone, liver, and brain metastasis. Given the few cases of bladder metastases reported in the literature, it is not clear if this location portends a worse outcome.

The question for urologists dealing with metastatic melanoma to the bladder is: does surgery play a role in the management, and if so, should management be transurethral resection (TUR) or cystectomy? Similar to genitourinary malignancies, metastasectomy for malignant melanoma is controversial, but retrospective data suggests metastasectomy may be associated with improved overall survival compared to systemic therapy alone.5 The role of metastasectomy in the era of newer effective systemic agents is likely to be answered in future studies, but at present, a multidisciplinary team of surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists should jointly devise a treatment strategy. In the other reported cases of metastatic melanoma to the bladder, treatment varied from observation, transurethral resection, and even cystectomy. The choice of surgical strategy should be based on overall prognosis, the patient's health status, presence of local symptoms attributable to bladder metastases, invasiveness of approach, and quality of life factors. Bladder metastases resulting in hematuria and voiding symptoms that can sometimes be managed by TUR, however TUR may not be sufficient to remove the entire tumor in many cases. Obviously, radical cystectomy or partial cystectomy for metastatic disease represents a markedly aggressive step compared to TUR, and such cases should probably be limited to those with solitary or limited metastatic disease and favorable prognostic factors. Unfortunately, our patient had concomitant brain metastasis and we felt there was limited evidence she would benefit from more invasive surgery. We elected to administer SBRT for her brain lesions, offer systemic therapy with combined checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy, and manage her bladder metastasis conservatively. Growing evidence suggests the efficacy of SBRT in melanoma, despite previous consideration that this tumor was ‘radioresistant,’ and possible synergistic effects of radiation with immunotherapy, the so-called ‘abscopal effect.’

Conclusion

Reported cases of metastatic melanoma to the bladder are rare. While long-term survival of patients with metastatic melanoma is rare, evolving treatment strategies and increasing acceptance of a survival benefit to metastasectomy in certain settings poses significant challenges to management. Integrating urologic treatments into a multidisciplinary strategy is important in managing these patients.

Conflict of interest statement

None to declare.

Footnotes

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Dasgupta T., Brasfield R. Metastatic melanoma. A clinicopathological study. Cancer. 1964;17:1323–1339. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196410)17:10<1323::aid-cncr2820171015>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein B.S., Kendall A.R. Malignant melanoma of the genitourinary tract. J Urol. 1984;132:859–868. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49927-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson M., Geller A.C., Tucker M.A. Melanoma burden and recent trends among non-Hispanic whites aged 15-49 years, United States. Prev Med. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maverakis E., Cornelius L.A., Bowen G.M. Metastatic melanoma – A review of current and future treatment options. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:516–524. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard J.H., Thompson J.F., Mozzillo N. Metastasectomy for distant metastatic melanoma: Analysis of data from the first multicenter selective lymphadenectomy trial (MSLT-I) Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2547–2555. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2398-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]