Abstract

A molecular test performed using fresh-frozen tissue was proposed for use in the prognosis of patients with pleural mesothelioma. The accuracy of the test and its properties was assessed under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–approved guidelines using FFPE tissue from an independent multicenter patient cohort. Concordance studies were performed using matched frozen and FFPE mesothelioma samples. The prognostic value of the test was evaluated in an independent validation cohort of 73 mesothelioma patients who underwent surgical resection. FFPE-based classification demonstrated overall high concordance (83%) with the matched frozen specimens, on removal of cases with low confidence scores, showing sensitivity and specificity in predicting type B classification (poor outcome) of 43% and 98%, respectively. Concordance between research and clinical methods increased to 87% on removal of low confidence cases. Median survival times in the validation cohort were 18 and 7 months in type A and type B cases, respectively (P = 0.002). Multivariate classification adding pathologic staging information to the gene expression score resulted in significant stratification of risk groups. The median survival times were 52 and 14 months in the low-risk (class 1) and intermediate-risk (class 2) groups, respectively. The prognostic molecular test for mesothelioma can be performed on FFPE tissues to predict survival, and can provide an orthogonal tool, in combination with established pathologic parameters, for risk evaluation.

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare and aggressive cancer that arises in the pleura and grows relentlessly into adjacent structures. Approximately 3200 new cases are diagnosed in United States each year, and the incidence worldwide is estimated to rise in the next 2 decades.1, 2 The World Health Organization classifies MPM into three major histologic types: epithelioid, sarcomatoid, and biphasic (composed of both epithelioid and sarcomatoid cells).3 Prognosis is generally poor in most MPM patients, with a median survival time between 4 and 12 months.4, 5 Patients with localized tumors may undergo surgical resection, such as extrapleural pneumonectomy or extended pleurectomy, followed by a combination of adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy6, 7; however, only a subset of patients is most likely to have sufficient survival benefit from this approach, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 20%.8

A clinically and pathologically accurate and internationally accepted staging system is essential for selecting patients for treatment and for assessing the benefit of new therapies.9 However, the validity of the current MPM staging system is questionable because it was derived from analyses of small-scale, retrospective surgical series that are difficult to apply to clinical staging, and uses descriptors for lymph node involvement, which may not be relevant to MPM.9 In the current clinical practice, several cancer-specific risk factors have been associated with survival; however, some of them, such as resection margins, stage, and lymph node status, can be accurately determined only after resection.10, 11, 12 Therefore, it is clinically important to identify prognostic factors to classify patients into groups with distinctly different outcomes before embarking on extirpative surgery.

We developed a molecular algorithm (the gene ratio method) that translates comprehensive RNA expression profiling data into simple clinical tests that are based on the expression levels of a relatively small number of genes.13 Genes differentially expressed between two clinically different conditions are identified in RNA-based expression profiling and are used in combination to calculate ratios of gene expression capable of predicting the clinical state associated with arbitrary patient samples.14, 15, 16 In particular, a four-gene, three-ratio gene expression score (GES) has been reported and subsequently validated in prospectively collected frozen tissue samples to predict overall survival in patients with MPM.17, 18, 19 In a multivariate model, the GES was independently significant after adjustment for lymph node status, tumor stage, and histologic subtype, indicating that this test appears to provide prognostic information additional to current pathologic staging methods. It has been suggested that the use of this molecular test, coupled with a multiplatform prognostic strategy, which includes lymph node status and histologic subtype determination, may be a predictor of overall survival and may lead to the selection of patients more likely to benefit from surgery.17 Patients predicted by this algorithm to have limited overall cancer survival may avoid futile operations.

In the current study, this MPM-prognostic GES has been adapted for use with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue on a high-throughput microfluidics real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) platform to assess its accuracy when performed under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-approved guidelines. The accuracy of the high-throughput FFPE test in classifying risk has been investigated in comparison to the published test using standard qPCR on frozen samples derived from the same tumor specimen.17 In addition, the high-throughput protocol was validated in the present study using an independent multicenter cohort of MPM tumor cases provided by the National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank (NMVB).

Materials and Methods

Patients and Sample Acquisition

MPM tumor specimens from cases included in the concordance study were collected at Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) (Boston, MA), from patients undergoing surgical extirpation with intent to cure, between 1999 and 2010. In this cohort, the survival time was calculated from the debulking surgery. Cases included in the independent validation study were collected at University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (Pittsburgh, PA) and the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA) between 1996 and 2013. These validation cases were obtained through the NMVB at University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. All de-identified specimens and matched clinical data were obtained under Institutional Review Board–approved protocols (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine NMVB protocol REN13070160/IRB0608194; University of Pennsylvania NMVB protocol 804329). The NMVB MPM validation set included 73 patients with FFPE biopsy specimens and clinically documented evidence of surgical resection of the tumor with diagnosis of histologic subtype. In this case, the survival time was calculated from diagnosis.

Sample Preparation and Quantitative PCR

Specimens processed at BWH were collected at surgery as discarded specimens and were fresh-frozen, stored, and annotated by the BWH tumor bank (Dana Farber/BWH Institutional Review Board protocol 98-063). Tumor sections (5 μm thick) from each sample were homogenized in Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA), and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) treatment was conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions to remove any genomic DNA contamination. RNA was quantified using an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE) and the ratio A260/A280 of ≥1.75 was considered as an indicator of adequate RNA purity. The integrity of the RNA was determined using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). RNA integrity number ≥7 was considered as an indicator of adequate RNA integrity. One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using TaqMan reverse-transcription reagents (Thermo Scientific) and random hexamers as primers. qPCR was conducted using a SYBR Green fluorometry-based detection system (Thermo Scientific), as previously described.13, 19 No-template controls that contained water instead of template were run in multiple wells on each reaction plate. The relative expression level of each of four selected genes (TM4SF1, PKM2, ARHGDIA, COBLL1) was determined by qPCR, using the following primers (forward and reverse, respectively): TM4SF1, 5′-GCACATTGTGGAATGGAATG-3′ and 5′-TCTGTCCTGGGTTGGTTCTT-3′; ARHGDIA, 5′-CAACGTCGTGGTGACTGG-3′ and 5′-TCGGTTAACCCGGAAAGAG-3′; COBLL1, 5′-GATGCGACAGAGTTTGCTGA-3′ and 5′-GGTGTGGCAGGGTAACATTT-3′; and PKM2, 5′-CTCGGGCTGAAGGCAGT-3′ and 5′-AATTGCAAGTGGTAGATGGCA-3′.

The expression level of one gene relative to the expression level of another gene formed the expression ratio of two genes in a single sample, as expressed by the equation [CT(gene 1) − CT(gene 2)]. The geometric mean of three-ratio combinations (TM4SF1/PKM2, TM4SF1/ARHGDIA, and COBLL1/ARHGDIA) was calculated as a GES, and its magnitude and direction (ie, >1 or <1) were determined in each sample. FFPE MPM biopsy samples from BWH and NMVB were cut to 5-μm sections and adhered to microscope slides. Tumor tissue was macrodissected and processed in a College of American Pathologists–accredited, CLIA-certified laboratory. RNA isolation, complimentary DNA generation, and qPCR were performed using standard operating procedures at the DNA Diagnostics Laboratory at St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center (Phoenix, AZ) as previously described.20 Briefly, RNA isolation was performed according to the Ambion RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). RNA quantity and quality were assessed using the NanoDrop 1000 system and the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100, and RNA was converted to cDNA using the Applied Biosystems High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies). cDNA samples underwent a 14-cycle preamplification step before being loaded to microfluidics gene cards. The gene-expression assay was performed in triplicate on an Applied Biosystems HT7900 system (Life Technologies).

Gene Expression Analysis

The cutoff of the GES was set at 1, as defined by the original test design.18 Specimens with GES >1 were assigned as type A, and these patients were predicted to have good overall survival. Conversely, specimens with GES <1 were classified as type B, and these patients were predicted to have poor overall survival. As previously reported,17 excluding GES values between 0.905 (exp−0.1) and 1.105 (exp+0.1) improved repeatability; therefore, classification of scores in this range was considered to be associated with reduced confidence.

We previously reported that the GES can be used in combination with current pathology staging methods to provide more accurate prognosis.17 When combining gene expression with clinical factors (lymph node status and histologic subtype), each risk factor was assessed as a binary variable (gene ratio: type A = 0, type B = 1; histologic examination: epithelial = 0, nonepithelial = 1; lymph node involvement: absent = 0, present = 1), and the sum of scores (combined score) was determined in each patient.17 Lymph node involvement was scored as present in two patients without N1-N3 status due to the documentation of positive nodes. MPM cases with a combined score of 0 were classified as class 1 (low risk); cases with a score of 1 and 2, as class 2 (intermediate risk); and cases with a score of 3, as class 3 (high risk).

Statistical Analysis

The 95% CIs for rates of sensitivity and specificity were based on the exact binomial distribution. The McNemar test was used for analyzing the concordance of FFPE-based classification with matched (from the same tumor) fresh-frozen samples. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Proportional hazards regression was used for estimating the hazard ratio (HR) for summarizing a survival difference in univariate and multivariate analyses. Data analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), with P values based on a two-sided hypothesis.

Results

Concordance Study

A total of 77 MPM matched frozen and FFPE samples were included in the analysis of concordance between BWH and the CLIA-laboratory. A schematic representation of the methods used for performing the tests using high-throughput FFPE and standard frozen protocols is shown in Figure 1. The clinical characteristics of the patients included in this cohort are listed in Table 1. Cases identified to have the same type assignment based on both the BWH (frozen) and CLIA-laboratory (FFPE) tumor analyses were considered concordant.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the research and clinical laboratory methods used for performing the test, using protocols for high-throughput formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) and standard frozen samples. The clinical laboratory method was performed according to standard operating procedures developed to allow for the use of FFPE surgical biopsy tissue samples of malignant pleural mesothelioma. qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients Included in the Study

| Parameter | Concordance cohort (n = 77) | Validation cohort (n = 73) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients alive at last follow-up, n (%) | 10 (10) | 36 (49) |

| Duration of follow-up from histologic diagnosis, median months (range) | 16.9 (1.3–109) | 11.5 (1–138) |

| Age at histologic diagnosis, median years (range) | 66 (38–86) | 63.5 (38–80) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 60 (68) | 63 (86) |

| Female | 17 (22) | 10 (14) |

| Histologic examination, n (%) | ||

| Epithelial | 49 (64) | 57 (78) |

| Mixed | 24 (31) | 14 (19) |

| Sarcomatoid | 3 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Desmoplastic | 1 (1) | |

| T classification, n (%) | ||

| T1 | 6 (8) | 5 (7) |

| T2 | 17 (22) | 23 (32) |

| T3 | 36 (47) | 33 (45) |

| T4 | 18 (23) | 9 (12) |

| Tx | 0 | 3 (4) |

| N classification, n (%) | ||

| N0 | 34 (44) | 25 (34) |

| N1 | 9 (12) | 11 (15) |

| N2 | 28 (36) | 31 (42) |

| N3 | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Nx | 6 (8) | 4 (5) |

The overall sensitivity for type B (poor prognosis) was 40% (95% CI, 16%–68%); the specificity for type A (good prognosis) was 94% (95% CI, 84%–98%) (P = 0.267) (Supplemental Table S1). The exclusion of the six cases in the low confidence score range (0.91 to 1.11) for either or both of a matched pair, previously defined in the analysis of the test properties,17 marginally increased the sensitivity to 43% (95% CI, 18%–71%), whereas the specificity was 98% (95% CI, 91%–100%) (P = 0.039). Misclassified samples were distributed mostly in the type B category, suggesting that FFPE-based classification is more likely to underpredict poor prognosis, although the overall concordance was high, with 83% (95% CI, 73%–91%) agreement between frozen and FFPE samples. A schematic representation of the results of the concordance study is included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the Concordance Study

| FFPE | Frozen |

|

|---|---|---|

| Type A | Type B | |

| Matched samples∗ | ||

| Type A | 58 | 9 |

| Type B | 4 | 6 |

| Matched samples, excluding low confidence range† | ||

| Type A | 58 | 8 |

| Type B | 1 | 6 |

FFPE, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded.

n = 77 (P = 0.266).

n = 71 (P = 0.039).

Clinical Demographics of the Validation Cohort

An independent validation cohort of 73 patients with documented treatment by surgical resection was identified from FFPE MPM surgical biopsy specimens obtained from the NMVB (Table 1). The median follow-up time was 11.5 months among 36 patients alive at last follow-up, and the median age of the cohort was 63.5 years. The majority of the specimens were obtained from male patients (86%). In these cases, data from histology and lymph node status were available for multivariable analysis.

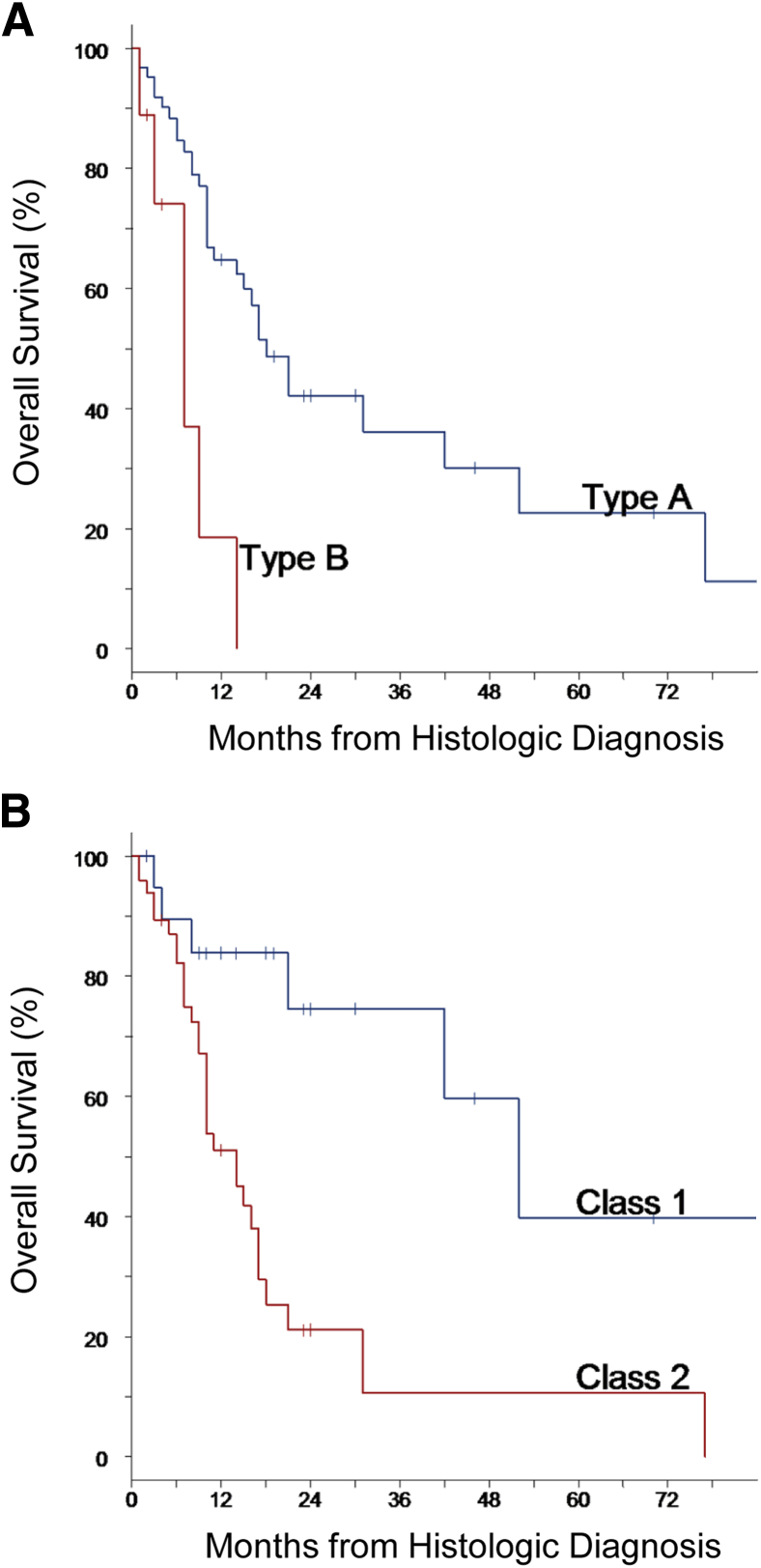

Validation of the Gene Expression Score Alone and in Combination with Clinical Factors

In the independent validation cohort, the GES identified 64 type A cases (good prognosis; 88%) and 9 type B cases (poor prognosis; 12%) (Supplemental Table S2). A significant difference in overall survival between the two groups was observed (P = 0.002), with median (95% CI) survival times of 18 (14–42) months versus 7 (1–14) months observed in type A and type B cases, respectively (Figure 2A). The median (95% CI) 1- and 3-year survival rates in type A cases were 65% (50%–76%) and 36% (20%–53%), compared with 19% (1%–55%) and 0% in type B cases.

Figure 2.

Overall survival in the validation cohort. Survival outcomes in the cases were predicted by gene expression score alone (A), or in combination with the clinical factors of histologic examination (epithelial versus nonepithelial) and lymph node involvement (absent or present) (B).

The combination of histologic examination and lymph node information with the GES resulted in stratification of the validation cohort into risk groups of 21 class 1 cases (29%) and 50 class 2 cases (68%). Only 2 (3%) cases were identified as high risk (class 3), including a patient who died within 1 month of surgery and another lost to follow-up after 4 months. The median (95% CI) 1- and 3-year survival rates in the class 1 group were 84% (58%–95%) and 75% (44%–90%), respectively, compared with 51% (35%–65%) and 11% (1%–33%) in the class 2 group (Figure 2B), with median survival times of 52 (95% CI, 21, upper limit not reached) months and 14 (10–17) months, respectively.

GES was a significant predictor of survival risk, with an unadjusted HR of 4.4 (P = 0.002), maintaining an independent effect in combination with histologic examination and lymph node status, with an HR of 4.3 (P = 0.003) (Table 3). In the univariate analysis, histologic subtype and lymph node status showed comparable effects on survival, with HRs of 2.4 (P = 0.018) and 1.9 (P = 0.088), respectively. The multivariate analysis found that both prognostic factors had slightly reduced survival effects in the presence of GES, with HRs of 2.1 (P = 0.043) and 1.7 (P = 0.162), respectively. In this cohort, lymph node status was not strictly significant as a prognostic factor by conventional statistical criteria due to modest power, but the HR estimates were consistent with the previously reported effect.17 Additional analysis also indicated that, similar to results reported from previous studies,17 the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control T status (T1-T2 versus T3-T4) was not an independent predictor of survival (P = 0.789 on univariate analysis).

Table 3.

Survival Analysis of Data from Validation Cohort

| Parameter | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| GES | 4.4 | 1.7–11.3 | 0.002 | 4.4 | 1.7–11.1 | 0.003 |

| Histologic examination | 2.4 | 1.2–4.8 | 0.018 | 2.1 | 1.0–4.3 | 0.043 |

| Lymph node status | 1.9 | 0.9–3.8 | 0.088 | 1.7 | 0.8–3.4 | 0.162 |

GES, gene expression score; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

In the past decade, the genetic profile of biological samples has been used for the identification of prognostic and predictive signatures associated with a number of diseases.20, 21, 22 Molecular tests have been applied to the management of several cancer types, and have been shown to add objective prognostic information to common pathology techniques used for determining a patient's risk.23, 24 Currently, risk factors used for predicting outcomes after surgery for MPM are histologic subtype, lymph node status, resection margin status, and stage.8, 25 However, these factors cannot be determined before major surgery, making them irrelevant to the decision to undergo resection. Therefore, the identification of preoperative prognostic factors is crucial for allowing patients to make informed decisions regarding treatment, and for classifying patients into groups with distinctly different outcomes to evaluate novel therapeutic approaches.

We have previously shown that the GES has robust predictive value and high technical assay performance in patients with MPM.17 The assay, based on a prognostic gene signature, was validated using fresh-frozen biopsy tissue, and was proved to be a significant independent predictor of risk in a cohort of 120 prospectively collected MPM cases.17 The GES also added significant prognostic value when combined with pathologically determined lymph node status and histologic subtype. In addition, the test and sample properties were also defined.17

The current study was designed to adapt the MPM prognostic GES to a standard clinical protocol applicable to FFPE tumor tissues, and to validate it in an independent (and external) cohort of MPM tumors, with the goal of performing the test in a College of American Pathologists–accredited and CLIA-certified laboratory for clinical purposes, independent of the research laboratory. The study reported herein has demonstrated that the molecular test results have high concordance between frozen and FFPE MPM tumor tissues and, therefore, that the development of a clinical test that assesses risk based on the GES in FFPE tissue is feasible.

Furthermore, the test was validated in an independent multicenter cohort of MPM FFPE tumor samples linked to outcome data. Our results also confirmed that the combination of the GES and the clinicopathologic factors of histologic subtype and lymph node status can be used for stratifying patients into three major classes of risk (low, intermediate, and high) that were predictive of overall survival in previously reported observations.17 The robustness of the methodology is illustrated by the ability of the test, alone as well as in combination with other risk parameters, to identify patient subgroups with highly divergent outcomes.

This study further defines some important advantages of gene expression profiling in MPM patients' prognosis. First, the technical concordance observed in this analysis extends the utility of the test beyond that in previous reports that validated the technical accuracy of the test using frozen tumor tissue alone. In addition, it allows for the development of standardized clinical laboratory protocols for the clinical application of the test. Finally, the analysis of the GES in an independent cohort of MPM cases, and the ability of the test to replicate the predictive outcomes in a cohort treated at different sites, illustrate the applicability of the test to samples collected at different institutions. A limitation of the study was the small subset of class 3 patients identified in the independent validation cohort, likely due to the fact that positive lymph nodes and nonepithelioid histologic examination are considered contraindications for surgery at some centers. Although the accuracy of the gene expression assay for predicting the risk associated with all MPM classes has been reported by Gordon et al,17 it would be important to identify a larger subset of these high-risk cases in future studies focused on the overall survival of patients based on analysis of FFPE tumor samples.

The GES described herein was designed to predict overall survival, and to provide an orthogonal tool for risk evaluation, alone or in combination with established clinical parameters. The results of the test performed before surgery can be combined with all of the other known predictors to select patients who can potentially benefit from surgical treatment. After surgery, when the lymph node status and the histologic examination are known, the combined score can be a predictor of overall survival after surgery.

The MPM prognostic gene ratio test described in this study has important clinical implications for both MPM patients and the physicians who care for them, such as the requirement of minimally invasive presurgical pleuroscopic biopsy to obtain the amount of tissue necessary for performing the test, and the accuracy of survival prediction before surgery compared with the currently accepted clinical TNM stage. The gene ratio test can be performed on tissue specimens obtained at the time of pleuroscopy and mediastinoscopy routinely conducted to confirm the diagnosis and surgical staging.

The expected clinical utility is that the test could be performed on FFPE tissue from the diagnostic biopsy specimen obtained through pleuroscopy or other minimally invasive methods, because such specimens are not routinely preserved frozen in standard pathology practice. Thus, after diagnostic biopsy and pathologic evaluation, the GES could be assessed shortly thereafter to include this prognostic information in the decision of surgical intervention. Because the primary objective of this study was to determine the feasibility and concordance of a laboratory and a clinical assay, surgical samples were used. In a previous study, we demonstrated that the gene expression ratio test, in combination with ex vivo fine-needle aspiration biopsy, can provide a simple tool for the diagnosis and prognosis of MPM patients26; however, future clinical validation using biopsy will be required.

In conclusion, the purpose of this work was to validate the GES in paraffin-embedded tissue and to determine its performance in an independent validation cohort. Since both goals were successfully accomplished, we conclude that there is sufficient rationale for the clinical application of this test with surgical specimens.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank partnering institutions, including Jonathan Melamed and Harvey Pass (New York University), Raja Flores (Mount Sinai School of Medicine), and Steven Albelda (University of Pennsylvania).

Footnotes

Supported by National Cancer Institute grant 2 R01 CA120528 (R.B.), by the International Mesothelioma Program, and by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health for funding National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank grant U24 OH009077-06. Castle Biosciences, which has licensed the prognostic test described herein from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH), supported some of the work through a grant to BWH and the laboratory of R.B. (Thoracic Surgery Oncology Laboratory).

Disclosures: This work was partially funded by Castle Bioscience through a research grant to Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and the laboratory of R.B. (Thoracic Surgery Oncology Laboratory). Castle Biosciences licensed the patent for the molecular tests described herein from BWH. R.W.C., C.E.J., K.M.O., D.J.M. are employees of, may hold stock options in, Castle Biosciences Inc. M.J.B. has received consulting fees from Empire Genomics, the scientific advisory board of NinePoint Medical, Omnyx (a joint Venture with University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and GE), and De-ID Data Corp. deidentification software (licensing agreement); and corporate support from API, Strategic Summit and Pathology Informatics 2014 Today, American Society for Clinical Pathology, Definiens, LabVantage, PathCentral–Aperio, Atlas Medical, Aurora Interactive, Data General, Halfpenny Technologies, Hamanatsu, HistoIndex, Knome, LifePoint Informatics, LigoLab Information Systems, Milestone, mTuitive, NinePoint Medical, NovoPath, Odin, Orchard Software, Phillips, Softek Illuminate, Software Testing Solutions, StarLIMS, Ventana, and Voicebrook.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.07.011.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Henley S.J., Larson T.C., Wu M., Antao V.C., Lewis M., Pinheiro G.A., Eheman C. Mesothelioma incidence in 50 states and the District of Columbia, United States, 2003-2008. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2013;19:1–10. doi: 10.1179/2049396712Y.0000000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbone M., Kratzke R.A., Testa J.R. The pathogenesis of mesothelioma. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:2–17. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.30227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tischoff I., Neid M., Neumann V., Tannapfel A. Pathohistological diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2011;189:57–78. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10862-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugarbaker D.J., Wolf A.S., Chirieac L.R., Godleski J.J., Tilleman T.R., Jaklitsch M.T., Bueno R., Richards W.G. Clinical and pathological features of three-year survivors of malignant pleural mesothelioma following extrapleural pneumonectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf A.S., Richards W.G., Tilleman T.R., Chirieac L., Hurwitz S., Bueno R., Sugarbaker D.J. Characteristics of malignant pleural mesothelioma in women. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:949–956. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.110. discussion 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burt B.M., Cameron R.B., Mollberg N.M., Kosinski A.S., Schipper P.H., Shrager J.B., Vigneswaran W.T. Malignant pleural mesothelioma and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database: an analysis of surgical morbidity and mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugarbaker D.J., Gill R.R., Yeap B.Y., Wolf A.S., DaSilva M.C., Baldini E.H., Bueno R., Richards W.G. Hyperthermic intraoperative pleural cisplatin chemotherapy extends interval to recurrence and survival among low-risk patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma undergoing surgical macroscopic complete resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:955–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill R.R., Richards W.G., Yeap B.Y., Matsuoka S., Wolf A.S., Gerbaudo V.H., Bueno R., Sugarbaker D.J., Hatabu H. Epithelial malignant pleural mesothelioma after extrapleural pneumonectomy: stratification of survival with CT-derived tumor volume. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:359–363. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rusch V.W., Giroux D., Kennedy C., Ruffini E., Cangir A.K., Rice D., Pass H., Asamura H., Waller D., Edwards J., Weder W., Hoffmann H., van Meerbeeck J.P. Initial analysis of the international association for the study of lung cancer mesothelioma database. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1631–1639. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31826915f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugarbaker D.J., Richards W.G., Bueno R. Extrapleural pneumonectomy in the treatment of epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma: novel prognostic implications of combined N1 and N2 nodal involvement based on experience in 529 patients. Ann Surg. 2014;260:577–580. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000903. discussion 80–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards W.G., Godleski J.J., Yeap B.Y., Corson J.M., Chirieac L.R., Zellos L., Mujoomdar A., Jaklitsch M.T., Bueno R., Sugarbaker D.J. Proposed adjustments to pathologic staging of epithelial malignant pleural mesothelioma based on analysis of 354 cases. Cancer. 2010;116:1510–1517. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugarbaker D.J., Flores R.M., Jaklitsch M.T., Richards W.G., Strauss G.M., Corson J.M., DeCamp M.M., Jr., Swanson S.J., Bueno R., Lukanich J.M., Baldini E.H., Mentzer S.J. Resection margins, extrapleural nodal status, and cell type determine postoperative long-term survival in trimodality therapy of malignant pleural mesothelioma: results in 183 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:54–63. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70469-1. discussion 63-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon G.J., Jensen R.V., Hsiao L.L., Gullans S.R., Blumenstock J.E., Ramaswamy S., Richards W.G., Sugarbaker D.J., Bueno R. Translation of microarray data into clinically relevant cancer diagnostic tests using gene expression ratios in lung cancer and mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4963–4967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bueno R., Loughlin K.R., Powell M.H., Gordon G.J. A diagnostic test for prostate cancer from gene expression profiling data. J Urol. 2004;171:903–906. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000095446.10443.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Rienzo A., Yeap B.Y., Cibas E.S., Richards W.G., Dong L., Gill R.R., Sugarbaker D.J., Bueno R. Gene expression ratio test distinguishes normal lung from lung tumors in solid tissue and FNA biopsies. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong L., Bard A.J., Richards W.G., Nitz M.D., Theodorescu D., Bueno R., Gordon G.J. A gene expression ratio-based diagnostic test for bladder cancer. Adv Appl Bioinform Chem. 2009;2:17–22. doi: 10.2147/aabc.s4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon G.J., Dong L., Yeap B.Y., Richards W.G., Glickman J.N., Edenfield H., Mani M., Colquitt R., Maulik G., Van Oss B., Sugarbaker D.J., Bueno R. Four-gene expression ratio test for survival in patients undergoing surgery for mesothelioma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:678–686. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon G.J., Rockwell G.N., Godfrey P.A., Jensen R.V., Glickman J.N., Yeap B.Y., Richards W.G., Sugarbaker D.J., Bueno R. Validation of genomics-based prognostic tests in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4406–4414. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon G.J., Jensen R.V., Hsiao L.L., Gullans S.R., Blumenstock J.E., Richards W.G., Jaklitsch M.T., Sugarbaker D.J., Bueno R. Using gene expression ratios to predict outcome among patients with mesothelioma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:598–605. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.8.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerami P., Cook R.W., Wilkinson J., Russell M.C., Dhillon N., Amaria R.N., Gonzalez R., Lyle S., Johnson C.E., Oelschlager K.M., Jackson G.L., Greisinger A.J., Maetzold D., Delman K.A., Lawson D.H., Stone J.F. Development of a prognostic genetic signature to predict the metastatic risk associated with cutaneous melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:175–183. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quackenbush J. Microarray analysis and tumor classification. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2463–2472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra042342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerami P., Cook R.W., Russell M.C., Wilkinson J., Amaria R.N., Gonzalez R., Lyle S., Jackson G.L., Greisinger A.J., Johnson C.E., Oelschlager K.M., Stone J.F., Maetzold D.J., Ferris L.K., Wayne J.D., Cooper C., Obregon R., Delman K.A., Lawson D. Gene expression profiling for molecular staging of cutaneous melanoma in patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:780–785.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onken M.D., Worley L.A., Tuscan M.D., Harbour J.W. An accurate, clinically feasible multi-gene expression assay for predicting metastasis in uveal melanoma. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12:461–468. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paik S., Shak S., Tang G., Kim C., Baker J., Cronin M., Baehner F.L., Walker M.G., Watson D., Park T., Hiller W., Fisher E.R., Wickerham D.L., Bryant J., Wolmark N. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baud M., Strano S., Dechartres A., Jouni R., Triponez F., Chouaid C., Forgez P., Damotte D., Roche N., Regnard J.F., Alifano M. Outcome and prognostic factors of pleural mesothelioma after surgical diagnosis and/or pleurodesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:1305–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Rienzo A., Dong L., Yeap B.Y., Jensen R.V., Richards W.G., Gordon G.J., Sugarbaker D.J., Bueno R. Fine-needle aspiration biopsies for gene expression ratio-based diagnostic and prognostic tests in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:310–316. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.