Abstract

Integrins, a diverse class of heterodimeric cell surface receptors, are key regulators of cell structure and behaviour, affecting cell morphology, proliferation, survival and differentiation. Consequently, mutations in specific integrins, or their deregulated expression, are associated with a variety of diseases. In the last decades, many integrin-specific ligands have been developed and used for modulation of integrin function in medical as well as biophysical studies. The IC50-values reported for these ligands strongly vary and are measured using different cell-based and cell-free systems. A systematic comparison of these values is of high importance for selecting the optimal ligands for given applications. In this study, we evaluate a wide range of ligands for their binding affinity towards the RGD-binding integrins αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ8, α5β1, αIIbβ3, using homogenous ELISA-like solid phase binding assay.

Structural and signalling responses of cells are tightly regulated by multiple adhesive interactions with the pericellular microenvironment, which promotes the physical networking of neighbouring cells and physical attachment to diverse extracellular matrix (ECM) networks. In addition, multiple environmental cues are mediated via adhesion receptors that bind selectively to external ligands and activate transmembrane signaling pathways that affect cell shape, dynamics, and fate1,2,3.

Integrins are a highly diversified class of key ECM adhesion receptors, that play essential biological functions in all higher organisms. They consist of two distinct transmembrane subunits, one α and one β, which connect the intracellular cytoskeleton and the pericellular ECM. As bidirectional signaling machines integrins respond to environmental cues (outside-in signaling) and at the same time, transduce internal signals (e.g. mechanical stress) to the matrix (inside-out signaling), thereby playing crucial roles in cell-cell communication and ECM4. In 1984, Pierschbacher and Ruoslahti discovered the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence in fibronectin as the minimal integrin binding motif5. Later, this sequence was found in other cell adhesive ECM proteins and described as a common cell recognition motif. These findings were readily followed by the development of multiple peptidic and non-peptidic RGD-based integrin ligands, with various degrees of specificity6,7,8,9. To date, eight of the 24 known human integrin heterodimers were shown to bind the RGD-recognition sequence10,11. Yet, despite their apparent similarity, these integrins can readily distinguish between different RGD-containing ECM proteins (e.g. vitronectin, fibronectin, fibrinogen etc.), and respond differently to the interaction with each one of them.

Given the involvement of integrin-mediated adhesion in the regulation of multiple physiological processes12 (e.g. cell migration, proliferation, survival, and apoptosis) as well as pathological processes (e.g. tumor invasion, metastasis), the development of integrin sub-type-exclusive antagonists is highly desirable. Indeed, integrin antagonists were shown to have high therapeutic potential13,14,15,16,17. Specifically, selective integrin ligands were widely used to target integrin-overexpressing tumors, as inhibitors of cancer angiogenesis18,19 and as blockers of excessive blood coagulation15. Modified integrin ligands were also used for carrying radionuclei or dyes for tumor diagnosis (using PET, SPECT or fluorescent probes)20, or for functionalization of adhesive surfaces and development of cell instructive biomaterials21,22,23,24.

Development of integrin subtype-selective compounds

Most ECM proteins display a very broad pattern of integrin binding activity. For example fibronectin preferentially binds to α5β1, αvβ6, αvβ8 and to αIIbβ3, although with different activities, while integrin αIIbβ3 is primarily expressed on platelets and binds to specific adhesive proteins, such as fibrinogen/fibrin, prothrombin and plasminogen. Nevertheless, despite their narrow specificity, integrin ligands that target αIIbβ3, should be used for therapeutic purposes with great care, since their excessive systemic administration might cause hemorrhagic disorders. On the other hand, short linear peptides, mimicking the RGD sequence showed a significantly lower binding to αIIbβ3, and had limited effect on platelet functions5. A few years later, we addressed the need of focusing on high affinity ligands toward αvβ3 while maintaining selectivity over αIIbβ3, by using cyclic RGD and incorporating one d-amino acid. The latter modification, based on a process called: “spatial screening”25,26,27,28, had a drastic impact on the backbone conformation, that changed the selectivity and affinity pattern of the cyclic peptides. These studies revealed that ligands presenting the RGD motif in an extended conformation with distances of 0.7–0.9 nm between the positively-charged arginine residue and the carboxyl group of aspartate, bind preferentially to αIIbβ329. In contrast, if the binding motif is more bent or kinked (as is the situation with the cyclic pentapeptide c(RGDf(NMe)Val) (=Cilengitide)30,31, ligands tend to bind preferably to other subtypes, such as αvβ3 and α5β1. The crystal structures of integrin antagonists docked into the αvβ3 or αIIbβ3 receptor pocket32,33,34, explained and corroborated this phenomenon, in retrospect (see Fig. 1 and discussion below).

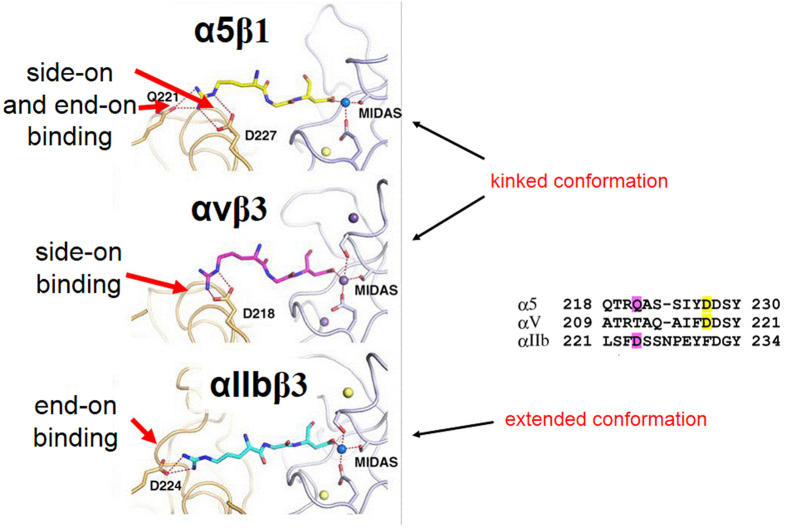

Figure 1. Illustration of different binding modes of a linear RGD peptide to different integrin subtypes.

Crystal structures of α5β1 (top), αvβ3 (middle), and αIIbβ3 (bottom) in complex with RGD ligands. Figure adapted from45.

Another crucial aspect of achieving selectivity for αIIbβ3, is the substitution of the guanidine group in the ligand by an amine. In all RGD-binding subtypes except for αIIbβ3, the guanidine group is bound via bifurcated salt bridges to the α-subunit (see Fig. 1), and an amine is not recognized. The binding mode in αIIbβ3 is slightly different and thus, Arg-to-Lys substitution leads to a strong enhancement of the selectivity for αIIbβ3. Nature has developed this alteration, resulting in obtaining selective αIIbβ3-specific ligands, avoiding crosstalk with other integrin subtypes.

Due to the similarity of the RGD binding regions in most integrins, it is not straightforward to achieve high selectivity and, at the same time, high affinity of small synthetic ligands, for distinct subtypes. In fact, most of the ligands described so far as subtype-selective have residual, yet significant affinity to other integrins as well. Recently, we, as well as others, were able to develop ligands with sufficient activity and selectivity to effectively discriminate between two closely related integrin subtypes, such as αvβ3 and α5β135,36,37 or αvβ638. Their functionalization enabled the selective imaging of αvβ3- or α5β1-expressing tumors in a mouse model, and the differential cell binding on different surfaces39,40. These molecules were developed by ligand oriented molecular design and later refined on the basis of X-ray structures of the integrins αvβ3 and αIIbβ332,33,41 and the homology model for α5β142,43,44. It is interesting to note that the later published crystal structure of α5β1 structurally confirmed the selectivity described for these ligands45.

Both, the αvβ3- and the α5β1-selective ligands bind the integrins via the kinked RGD motif, but differences are found in the binding mode of the arginine side chain. As illustrated in Fig. 1, which depicts a linear RGD-ligand in the binding pocket, the guanidine group of arginine is binding in a side-on manner to the Asp218 of the α-subunit of αvβ3, forming a bidendate salt bridge. In addition to this side-on interaction (Asp227 in α5), an end-on interaction of guanidine and Gln221 can be observed in the crystal structure of α5β145. Keeping this difference in mind, the selectivity of the ligands can be explained as follows: the amino pyridine in sn243interacts side-on with the αv-pocket but does not allow an end-on binding due to sterical hindrance, thus reducing strongly the α5β1 affinity. On the other hand, 44b has a full guanidine function allowing side-on and end-on interactions. Recently, we described a way how this small difference between the αv- and the α5-binding pocket can be utilized to design selective peptidic integrin ligands. By alkylation of the Nω of the guanidine group of arginine, the α5-specific end-on interaction is blocked, leading to a shift in selectivity for αv-integrins46.

Apart from targeting integrins αvβ3, α5β1, or αIIbβ3, other clinically relevant integrin subtypes have been explored16. For instance, several linear peptides, containing a helical DXLLX motif, were shown to selectively bind αvβ6 and αvβ8, and display low affinity towards all other subtypes. The biological role of αvβ6 and αvβ8 is quite similar, as they are both participating in the activation of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) by interacting with the same endogenous ligands TGF-β1 and TGF-β347. Finally, αvβ3 and αvβ5 share very similar biological roles (stimulate angiogenesis), but they perform this task via different mechanisms48. Nevertheless, their close structural similarity hampers the development of selective ligands to these integrins49,50.

The aims of this work

Since the discovery and first application of integrin-binding RGD peptides in the 1980s, and based on their great impact in medicine, biology, and biophysical sciences, the design and use of synthetic integrin ligands attracts much attention. Most of the current research is focused on the discovery of new integrin-selective ligands and their use for drug delivery, diagnosis, and tumor imaging, which are crucial for developing effective personalized medical platforms.

However, unequivocally ascribing a specific biological role to one integrin receptor remains problematic. Even when high binding affinity towards one distinct integrin subtype is achieved, it often remains unclear whether the observed biological effect is not based on a residual effect on another subtype. This may be attributed to the fact that most studies so far have only focused on the selectivity between a reduced subset of integrins, e.g. αvβ3 vs. αIIbβ3, or αvβ3 vs. α5β1, but have totally neglected the influence of other closely related integrins of the RGD-binding family. This is particularly problematic as integrin expression strongly depends on cell and tissue type, crosstalk within distinct integrin subtypes, time point of study, and biological environment (e.g. tissue type). Last but not least, the activities reported for integrin ligands are usually evaluated using different experimental protocols and are, thus, highly variable.

Consequently, no reliable comprehensive comparison of the IC50-values of biologically prominent integrin ligands has been made, so far. Newly designed integrin ligands have seldom been evaluated for their selectivity against a full panel of RGD-binding integrin subtypes, mainly because there were no reliable testing systems established.

In this work, we have evaluated a large number of well-known and widely used integrin-targeting molecules using the same standardized competitive ELISA-based test system, by measuring the inhibition (i.e. IC50 values) of integrin binding to immobilized natural ECM ligands. In order to facilitate a direct comparison, we show here (Tables 1 and 2) the affinity values determined with our test system, which always contained reference compounds to standardize the biological data. For some ligands, IC50 values were already reported in the literature and the inhibitory activities might slightly deviate from our present data. However, we consider that a direct comparison under identical conditions is very important and thus only represent the data determined during this work. This study includes RGD-based linear and cyclic peptides, peptide-mimetics as well as commonly used reference compounds. Furthermore, in this study we demonstrate, with carefully selected molecules, how functionalization of integrin ligands (e.g. with chelators, anchoring groups) can affect their binding affinity and selectivity. The investigated integrin subtypes studied here include: αvβ3 and αvβ5 (both binding to vitronectin), αvβ6 and αvβ8 (binding to LAP), α5β1 (binding to fibronectin) and αIIbβ3 (binding to fibrinogen), which are all RGD-binding (the only missing RGD-binding integrins are αvβ1 and α8β1, which could not be screened in our test system) and have relevant clinical implications. Since none of the presented ligands have previously been evaluated against such an exhaustive panel of integrin subtypes, the results of this study will provide unprecedented insights into the binding and selectivity profiles of synthetic integrin ligands, thus being of great value for the further development of integrin inhibitors for medical applications. In general, these binding activities correlate very strongly with the inhibition of signal transduction and with the binding affinity of the biochemically highly complex focal adhesions to ECM proteins.

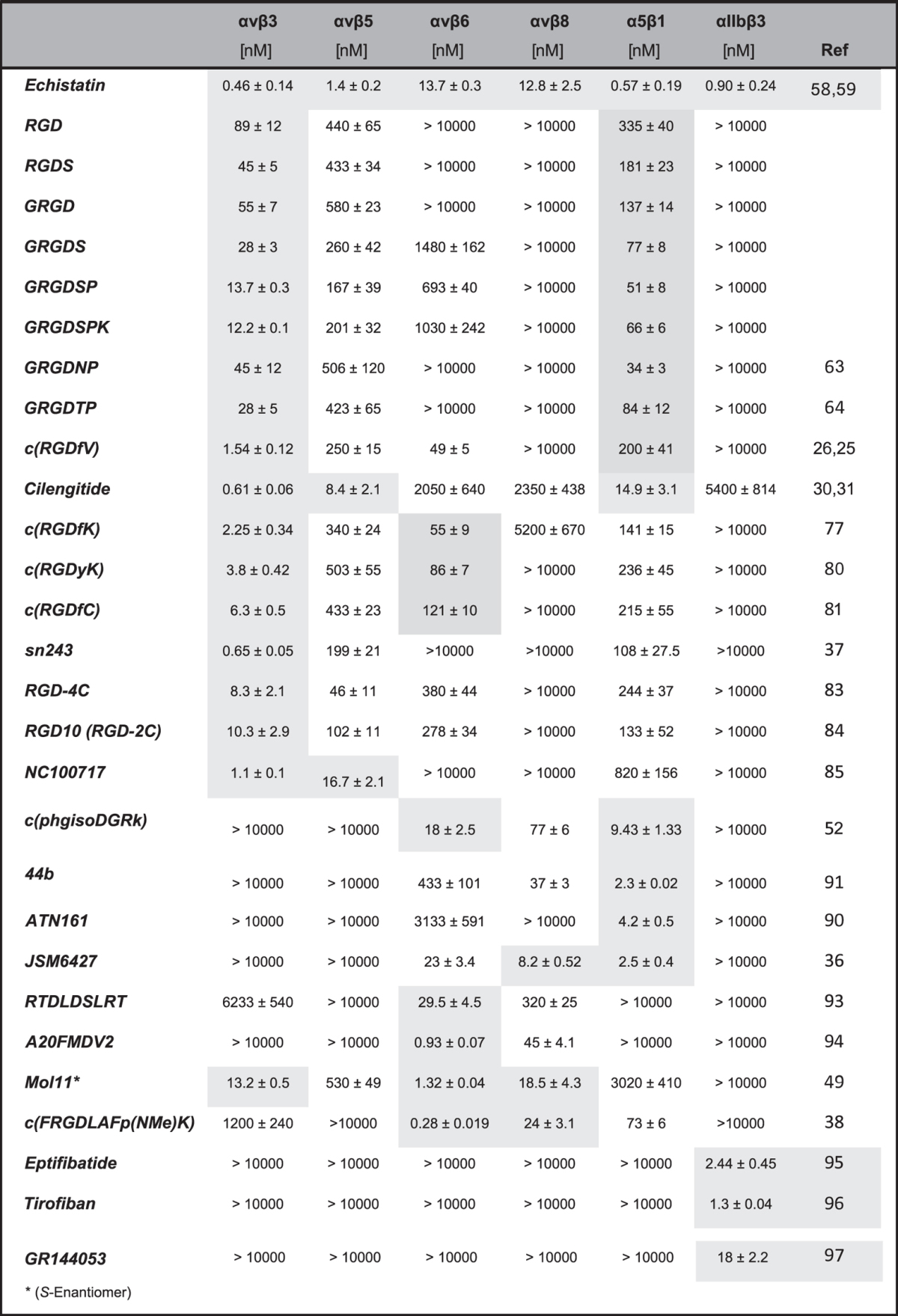

Table 1. IC50-values for the integrin ligands investigated for the subtypes αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ8, α5β1, and αIIbβ3.

Specificity or subtype with the lowest IC50-value are highlighted. All values were referenced as given in the description of the assay and in the SI.*(S-Enantiomer).

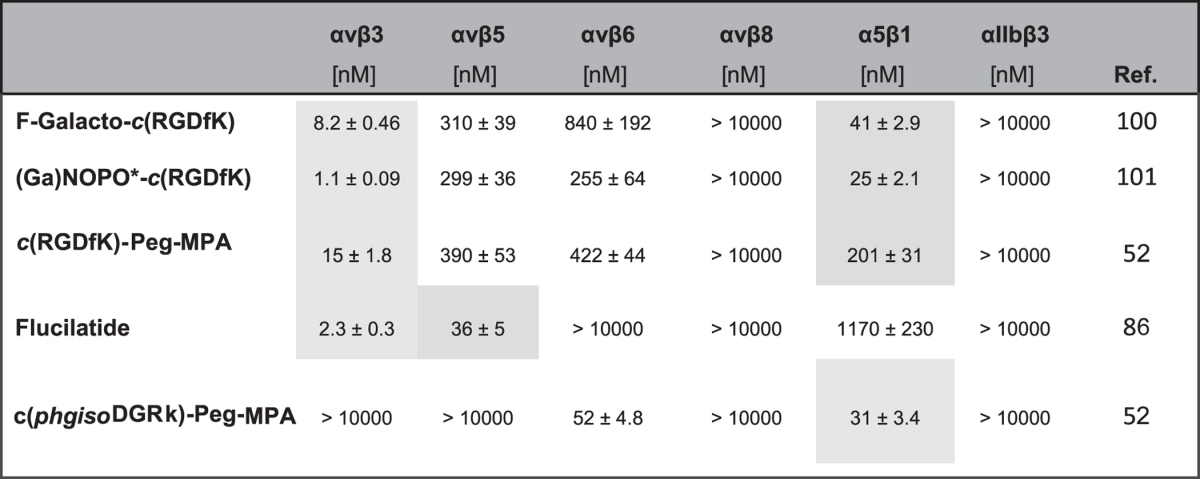

Table 2. IC50-values for the functionalized integrin ligands investigated for the subtypes αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ8, α5β1 and αIIbβ3.

Specificity or subtypes with the best IC50-values are highlighted, respectively. All values were referenced as given in the description of the assay and in the SI.*NOPO 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4-bis[methylene(hydroxymethyl)phosphinic acid]-7-[methylene(2-carboxyethyl)phosphinic acid.**21-amino-4,7,10,13,16,19-hexaoxaheneicosanoic acid.

An overview of the main approaches for testing integrin subtype-specific ligands

For the development and optimization of biologically active integrin ligands it is of utmost importance to use a reliable and reproducible test system, which yields values for biological activity with low statistical variance and high precision. A careful revision of previously published integrin-binding affinity data for well-known integrin ligands seems to indicate clear differences between the methods used. In general, cell-based methods are strongly dependent on the experimental condition of the study. Thus, the affinity data obtained for the same compound and the same integrin may greatly vary in different cell-based studies. In contrast, non-cellular systems, which are based on the use of isolated integrin receptors, tend to exhibit better biochemical precision and reproducibility. The major drawback of these methods, however, is the fact that they represent a simplified and artificial system, which does not fully mimic the intricate nature of integrin-ligand interactions and the subsequent response of the adhesome-associated signaling. Thus, an efficient combination of both systems is highly recommended for an optimal and efficient development of integrin-targeting drugs. In the following section, several cellular and non-cellular tests are briefly described.

In vitrocellular tests have been widely used to obtain integrin affinity data. A well-established and commonly used method is based on the concentration-dependent inhibition of cell attachment to a surface that is usually coated with the native cell adhesive proteins5. Prior to the test, cells are plated on a surface and afterwards incubated with the soluble compound in different concentrations. Alternatively, cells are incubated in the presence of the integrin ligand, which blocks their attachment to the surfaces. For the evaluation, the attached cells are viewed by transmitted light microscopy, by fluorescence microscopy (in cases when the cells are tagged), or upon use of other functional imaging approaches. Such tests can be performed with a variety of cell types (e.g. NRK-epithelial cells, MG-63, MDA-MB-43551 or REF5252), as well as with platelets isolated from platelet-rich plasma. Another popular cell-based technique is the calculation of integrin binding affinities based on ligand binding assays53. Suspended or adherent cells are incubated with increasing concentrations of an integrin ligand, and afterwards with a radiolabeled ligand that also shows integrin-binding affinity, such as 125I-Echistatin or 125I-c(RGDyK). The radioligand is therefore competing with the compound for binding to the integrin receptors on the cell surface and serves as an internal standard reference for the binding affinity. As described for the cell adhesion assay, a great choice of integrin expressing tumor cell lines as well as epithelial cells are available, such as 293-b β354 or U87MG glioblastoma55.

Cell-based tests hold great potential to evaluate not only ligand binding but also its capacity to trigger biological responses relevant for the physiological context. This holds true at least for cases in which the “reporter” cell type is physiologically relevant. It is noteworthy that cellular tests possess some serious intrinsic limitations that are of particular importance during drug development. The major drawback is the limited control over homogeneity in the levels of integrin expression present in the different cell lines used, or even in individual cells in the tested population. Typically, there is one highly overexpressed integrin subtype presented on the surface, but there may also be other minor populated integrin subtypes to which the tested compounds may bind. It is even more problematic that these subtype expression levels may change over time. In addition, the total surface receptor density can strongly vary depending on specific conditions (number of passages in culture, presence of other integrins, cell culture conditions, state of cell cycle etc.). For example, a phenomenon known as “integrin crosstalk” has been proven for αvβ3 and α5β1. Specifically, α5β1 integrin was shown to modulate (up or down) the expression of another subtype and thus significantly alters the expression pattern56. Consequently, the comparison of affinity data measured for different cell lines is highly challenging.

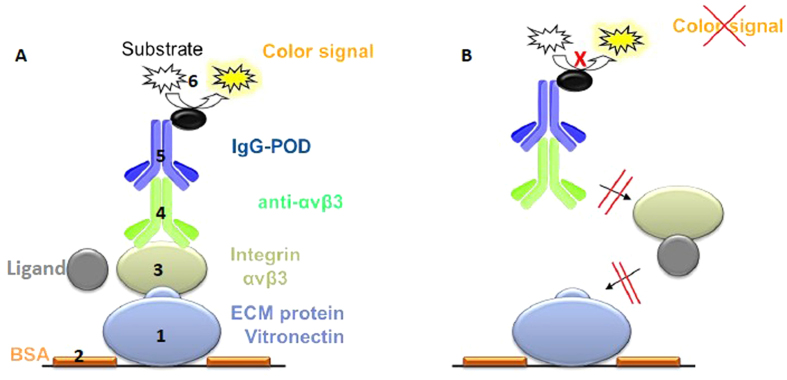

Tests carried out in cell-free systems, use isolated extracellular domains of integrins in conjunction with ECM proteins, either extracted from human tissue or produced by recombinant methods. Most of these tests are based on competitive solid phase binding assays, in which one component is bound to the multi-well plate and in a subsequent step, soluble ligands are added, testing their capacity to block the binding to that component. Mainly two procedures are described in the literature, differing in the molecule used to coat the surfaces: the isolated integrin extracellular domains or the ECM protein. In the first case, the integrin is coated on the surface, followed by an incubation with a mixture of the native ECM protein and increasing concentrations of the ligand of interest49. In an alternative test system, the natural ECM protein (vitronectin for αvβ3 and αvβ5, LAP (TGFβ) for αvβ6 and αvβ8, fibronectin for α5β1 and fibrinogen for αIIbβ3) is immobilized onto the surface, and the soluble integrin, together with a serial dilution of the inhibitory ligand, is added afterwards57. The read-out in both procedures is usually done in an ELISA-like manner by using conjugated antibodies recognizing the integrin head groups. A detailed schematic illustration of the different steps of the integrin binding assay is presented in Fig. 2. In comparison to many other test systems, this system allows the accurate (SD~10%) and reproducible determination of IC50 values for almost all RGD-binding integrin subtypes. For a detailed description of the reference to the SI. As the quality of the integrins strongly depend on the batch and providers a reference compound always have to be used for each test plate as internal standard (we used: Cilengitide, c(RGDf(NMe)V) (αvβ3–0.54 nM, αvβ5–8 nM, α5β1–15.4 nM), linear peptide RTDLDSLRT (αvβ6–33 nM; αvβ8–100 nM) and tirofiban (αIIbβ3–1.2 nM).

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

(A) 1. Each well (96-well plate) is coated with an ECM protein (e.g. vitronectin for αvβ3). 2. Uncoated surface is blocked by bovine serum albumin (BSA). 3. ECM protein competes with the tested ligand for binding to the soluble integrin (e.g. αvβ3). 4. Integrin bound to ECM protein is detected by an integrin-specific primary antibody. 5. Secondary antibody, conjugated with a peroxidase (POD), detects bound primary antibody. 6. Peroxidase converts a colorless substrate into a colored substrate (TMB, 3,3′,5,5′-tetrametylbenzidine). (B) The ligand inhibits binding of the coated ECM protein to the integrin. Consequently, steps 3–6 are blocked and no color signal can be detected.

Preliminary studies in our laboratories comparing the two methods (surface-bound integrin vs. soluble integrin) revealed significant differences in the antagonistic activity of control ligands in regards to the integrin subtype used. Whereas very similar IC50 values were found regardless of the method used for integrins αvβ3 or αvβ5, the activity towards α5β1 seemed to be highly dependent on the experimental protocol. The drug Cilengitide exhibited very high affinity (in the low nanomolar range) towards soluble α5β1 when fibronectin (i.e. the natural ECM ligand) was immobilized on surfaces. However, coating of the integrin and subsequent incubation of Cilengitide with fibronectin generally resulted in low antagonistic activities and poor reproducibility within assays (unpublished data). This was already observed in our stem peptide c(RGDfV)26, and may be attributed to the possible denaturation of α5β1 integrin.

Results and Discussion

The gold standard integrin inhibitor, Echistatin

The disintegrin Echistatin was first isolated in 1988 from snake venom as an effective inhibitor of platelet-fibrinogen interaction, as well as of platelet aggregation58. This small folded protein contains an RGD-sequence in a well-exposed loop which was described to bind to αIIbβ3, αvβ3, αvβ5, and α5β1 with very high affinity59. Since the Tyr-31 residue of Echistatin can be labeled with 125I using a standard procedure has turned this compound into a commonly used positive control for many competitive cellular integrin binding assays60,61. We therefore included Echistatin in our study to determine its selectivity profile and to compare its binding activities to those previously obtained from cellular assays. Echistatin showed a very broad affinity pattern. It binds to the whole panel of investigated integrins with IC50-values in the low nano-molar range (Table 1). As already reported, it shows particularly low IC50-values for αvβ3 (0.46 nM), α5β1 (0.57 nM), and αIIbβ3 (0.9 nM). Interestingly, Echistatin exhibited the lowest IC50-values for these integrins compared to all other compounds investigated within this study. Thus, it also represents an ideal candidate to be included as a positive control in cell-free integrin binding tests.

Linear RGD integrin inhibitory peptides

The RGD-sequence was originally discovered as the minimal binding epitope of fibronectin and has extensively been investigated over the last decades. Moreover, it has been shown that the presence and chemical nature of flanking residues have a strong influence on its activity5. Thus, early studies with the RGD-motif were conducted with linear tri- to heptapeptides, based on the sequence found in fibronectin. In our study, the following linear peptides were included: RGD, RGDS, GRGD, GRGDS, GRGDSP,and GRGDSPK. In original reports, these peptides were described to bind to αvβ3 and αvβ5, but also showed relatively good IC50-values for the integrin subtypes α5β1 and αvβ6, as well as low affinity for αIIbβ362. Apart from the compounds mentioned above, GRGDNP63 and GRGDTP64 peptides were also included in our test system, as they are frequently used in biological studies. Especially, GRGDNP has been described to prefer binding to α5β1. In our evaluation, all linear peptides showed the lowest IC50-values for the integrin subtype αvβ3 (12–89 nM), with IC50-values for αvβ5 ranging from 167 to 580 nM and for α5β1 from 34 to 335 nM. These peptides generally displayed high IC50-values towards αvβ6 and αvβ8. More surprisingly, none of the linear peptides exhibited an IC50-value below 10 μM on αIIbβ3. These results demonstrate that the linear RGD peptides are active on integrins αvβ3, αvβ5, and α5β1, and selective against αvβ6, αvβ8 and αIIbβ3. As presented in Table 1, the residues flanking the RGD-motif essentially contribute to the binding affinity for αvβ3 (and to a lower extent for α5β1 and αvβ5). In particular, the IC50-value to αvβ3 increases 7-fold from the linear tripeptide fragment RGD (89 nM) to the heptapeptide GRGDSPK (12.2 nM).

Cyclic RGD peptides

A major disadvantage of linear peptides is their low stability regarding enzymatic degradation, limiting their applicability for in vivo studies65. This can be significantly improved by cyclization and incorporation of a d-amino acid residue, as illustrated by cyclic pentapeptides of the formula c(RGDxX) and cyclic hexapeptides66. Moreover, reduction of the conformational space by cyclization can improve the biological potency of linear peptides when the bioactive conformation is matched67. One of the first cyclic compounds that was developed and used in cellular studies was c(RGDfV) which showed outstanding affinity for αvβ3, while retaining total selectivity against αIIbβ3. This core structure was later modified to develop a series of new ligands with improved activity and selectivity profiles68,69. Extensive Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) studies on the model sequence c(RGDxX) showed, that the presence of an aromatic amino acid in the d-configuration (i.e. d-Phe, d-Tyr, d-Trp) at the position 4 (residue x) was essential for the αvβ3-binding affinity, whereas the amino acid at position 5 (residue X) had little effect on the biological activity68,69. Based on the stem peptide c(RGDfV), Cilengitide, c(RGDf(NMe)V), the most active cyclic pentapeptide described to date, was developed via a systematic N-methylation scan. Cilengitide has a half-life in man of about four hours and is not metabolized systemically70. It became a drug candidate in phase II and III clinical studies for the treatment of different tumors71,72,73,74, however failed in phase III as drug against glioblastoma. Despite its extraordinarily low IC50-value for αvβ3 and αvβ5, the higher, but still significant value for α5β1 subtype is often neglected75. In this regard, our study clearly shows that this compound has also a remarkably low IC50-value for α5β1 (14.9 nM). Noteworthy, the IC50 for αvβ3 (0.61 nM) and αvβ5 (8.4 nM) were the highest obtained among all synthetic peptides developed and studied. As previously indicated, the valine residue can be substituted by almost any other amino acid66. Hence, for biophysical or medical applications where a functionalization or ligation of integrin ligands is needed, the derivative c(RGDfK)76 is often used. Lys has been found to be a good anchoring point for the attachment of functional units not only because it does not affect the binding affinity of the stem peptide significantly, but also because it easily allows the linkage of other chemical groups via the free amine. A pilot study by us used acrylate-functionalized derivatives of c(RGDfK) to mediate the adhesion of osteoblasts on a polymethylmetacrylate (PMMA) surface77. Since that time, c(RGDfK) and also c(RGDfE) were functionalized for a large number of biological applications78,79. Other cyclic penta-peptides used for functionalization are c(RGDyK)80 as well as c(RGDfC)81, are both included in our study. Just like the linear peptides, all of the cyclic pentapeptides of the type c(RGDxX) tested showed moderate to low IC50-values for αvβ3, αvβ5, and α5β1, and no binding to αIIbβ3, which is of major importance for in vivo applications. Noteworthy, all the cyclic peptides displayed lower αvβ3 IC50-values (i.e. in the range of 1.5 to 6 nM) compared to the linear derivatives, and followed the order c(RGDfV) < c(RGDfK) < c(RGDyK) < c(RGDfC). Therefore, cyclic RGD-peptides should be the preferred choice when high αvβ3-binding activities are required. The IC50 values for αvβ5 and α5β1 varied from 250 to 503 nM and from 141 to 236 nM, respectively. Interestingly, all the cyclic compounds showed relatively low IC50-values for αvβ6 (49–75 nM), which has not been discussed in any of the references so far.

Ruoslahti et al. discovered the RGD-containing double cysteine-bridged (1–4, 2–3) peptide RGD-4C82 (ACDCRGDCFCG) by phage display and reported a low IC50-value towards the subtypes αvβ3 and αvβ5, and specificity over α5β1. This peptide represents one of the most commonly used molecules in cellular tests and in in vivo studies and has been conjugated to target αvβ3-overexpressing cells83. To reduce the synthetic complexity that arises from two disulfide bridges, Hölig et al. developed the single cysteine-bridged peptide RGD10 (GARYCRGDCFDGR)84, which has the same IC50 value and selectivity properties as the original RGD-4C, and has been functionalized for different applications as well, (e.g. for surfaces coating or targeting liposomes). In our studies, the RGD-4C peptide exhibited an IC50-value for αvβ3 of 8.3 nM, which is comparable to that observed for the best linear RGD-sequences but considerably lower than that of cyclic RGD-containing penta-peptides. Furthermore, it also shows a good value for αvβ5 (46 nM), a high IC50-value for αvβ6 and α5β1, and no affinity for αvβ8 and the platelet integrin αIIbβ3. As reported in other studies, RGD-10 exhibits a similar pattern of bioactivity, though with a trend towards increased αvβ3/αvβ5 selectivity: the IC50 for αvβ3 remains almost the same, whereas the αvβ5 affinity drops to 102 nM. Based on the RGD-4C peptide, Indrevoll et al. developed a PEGylated bicyclic, mono cysteine-bridged peptide with the sequence KCRGDCFC (NC100717)85 targeting the αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin subtype. This scaffold is the targeting unit of functionalized compounds (chelators and dyes), e.g. the 18F-labeled compound 18F-AH111858 (Fluciclatide86, GE), described in detail in the section of functionalized molecules. NC100717 showed a low nanomolar IC50-value for αvβ3 (1.1 nM) and αvβ5 (41 nM) in our test system. Nonetheless, for application of disulfide-bridged cyclic peptides it may be of interest to consider the stability of disulfide bridges in vivo87. Finally, another integrin binding motif in fibronectin is the inverse sequence isoDGR which is based on the NGR motif after in situ rearranging from asparagine to iso apartate88,89. The integrin subtype selectivity strongly varies depending on the flanking residues of the sequence. Recently, the compound c(phgisoDGRk)50, which is bi-selective for αvβ6 and α5β1, was identified and used for cellular studies. In our test system, it could be shown here that the compound moreover binds to αvβ8 as well.

Peptidomimetics and other ligands

The non-RGD linear pentapeptide Ac-PHSCN-NH2 was derived from the synergy domain of fibronectin and is clinically developed under the trade name ATN16190 for the treatment of several solid tumors as it is highly active for the α5β1 subtype, with some affinity for αvβ3 and αvβ516. Interestingly, ATN161 showed a clear selectivity for α5β1 (4.2 nM) in our testing system, being essentially inactive for all other integrins investigated.

The non-peptidic compound JSM642736 was designed by Stragies et al. and later developed in clinical phase for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration as it strongly inhibits neovascularization in the eye. It is described to be a relatively selective α5β1 antagonist, although values for αvβ6 and αvβ8 were not published. Indeed, we found JSM6427 to be tri-selective for α5β1 (2.5 nM), αvβ6 (23 nM), and αvβ8 (8.2 nM).

Recently, we reported the synthesis and binding affinity of the highly active αvβ3-selective sn24337 and the α5β1-selective 44b91 peptidomimetic ligands. In a proof-of-concept study, these compounds were functionalized and used for molecular imaging92 as well as for biophysical studies39,40, showing their potential to discriminate the two integrin subtypes αvβ3 and α5β1 both, in vitro and in vivo. Here, we also included them to evaluate their full pattern of integrin selectivity, and found, besides the expected high activities for the corresponding subtype (sn243: 0.65 nM αvβ3; 44b: 2.3 nM α5β1), a low nanomolar IC50-value for αvβ8 for 44b (37 nM).

Integrin αvβ6-binding ligands

The α-helical binding motif DLXXL, an αvβ6 subtype-specific binding motif, was initially discovered by phage display and later shown to be also present in the natural αvβ6 ligand latency associated peptide (LAP). Two compounds containing this motif are included in this study as they have extensively been used for addressing selectively αvβ6-expressing cells in vivo, e.g. as targeting unit for molecular imaging. The RTD containing 9-mer peptide RTDLDSLRT93 as well as the 20-mer peptide A20FMDV294, which is derived from a foot and mouth disease virus peptide (sequence: NAVPNLRGDLQVLAQKVART), were proven to be subtype-selective in our study and exhibited an IC50-value of 29.5 and 0.93 nM for αvβ6, respectively. The peptidomimetic compound Mol1149, which was described as the first αvβ6 selective small molecule ligand, was resynthesized for this study as an enantiomerically pure (S-enantiomer) compound and indeed showed a very low IC50-value for αvβ6 (1.3 nM), but also good values in the lower nanomolar range for αvβ3 (13.2 nM), and αvβ8 (18.5 nM). Recently, we were able to develop the cyclic peptide c(FRGDLAFp(NMe)K)38, which mimics the binding epitope of the helical DLXXL-motif. The IC50 of this peptide was determined to be 0.28 nM for αvβ6, the highest affinity among the compounds investigated.

Integrin αIIbβ3-binding ligands

The αIIbβ3 integrin receptor, also known as glycoprotein receptor (GP)-IIb/IIIa, is expressed uniquely on the surface of platelets and megakaryocytes, a type of platelet-producing cells in the bone marrow. By binding to its natural ligand fibrinogen, αIIbβ3 is involved in primary hemostasis during platelet formation. Thus, application of αIIbβ3 ligands was earlier explored as a clinical approach for anti-thrombotic therapy15. Today, there are two FDA-approved drugs targeting selectively the αIIbβ3 receptor, Intrifiban (Eptifibatide)95 and Tirofiban(Aggrastat)96, both clinically used for patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Eptifibatide is a cysteine-bridged cyclic RGD-containing hexapeptide. It was first described in 1993 as a potent subtype-selective integrin antagonist and is, as well as the small molecule αIIbβ3 inhibitor Tirofiban, used both clinically and preclinically. Another αIIbβ3 selective compound included in this comparison of integrin ligands is GR14405397. It is described as an orally available, highly potent subtype-selective fibrinogen inhibitor and is used in many preclinical studies. In our test system, these three compounds have been confirmed to be selective αIIbβ3 inhibitors. The lowest αIIbβ3 IC50-value was determined for Tirofiban (1.3 nM), followed by Eptifibatide (2.8 nM) and GR144053 (18 nM).

Functionalized compounds

Many of the integrin ligands that are used for biophysical or medical experiments require a functional unit (e.g. for a strong covalent binding to the surface) or a chelator for molecular imaging. For that reason, the bioactive moiety is linked to this functionality via a spacer that separates the two entities of the molecule. Ideally, by using the right anchoring point in the molecule, the loss of activity upon functionalization is low. Nevertheless, the size, lipophilicity, and other parameters like the rigidity of the functional as well as the spacing unit can influence the binding of the bioactive moiety to its target98,99. To estimate the influence on the IC50-values after modification of the ligand, five compounds were chosen as examples (Table 2). Among three of them, c(RGDfK), which is functionalized via its lysine side chain, represents the bioactive targeting unit. The IC50-value of the unmodified ligand was determined to be 2.3 nM for the αvβ3 integrin subtype (Table 1). After modification to F-Galacto-c(RGDfK)100 (for molecular imaging) and c(RGDfK)-Peg-MPA) (MPA = mercapto propionic acid), the IC50 moderately decreased to 8 and 15 nM, respectively. Exactly the opposite, namely a better αvβ3 IC50 was observed for the (Ga)NOPO-c(RGDfK) (1.1 nM)101. This phenomenon could already be observed for previously published compounds and can be explained, inter alia, by charge effects and/or altered van-der-Waals interactions. For example, large substituents like chelators possess a high surface area and can randomly interact via unspecific van-der-Waals interactions with parts of the protein. This weak interaction decreases the koff-rate and thus can lead to IC50-values compared to the original targeting peptide alone. Concerning the selectivity profile of the modified compounds, no changes are observable. This is also found for the αvβ6/α5β1 bi-selective peptide c(phgisoDGRk), where the selectivity is not affected but the IC50-value for the two integrins doubles (2-fold) after functionalization to c(phgisoDGRk)-Peg-MPA)52. Fluciclatide, an imaging agent developed by GE Healthcare, consists of NC100717 as targeting unit84. For this example, the IC50-value for αvβ3 decreased 3-fold and no change in selectivity was observable. To sum up, the functionalization of a bioactive molecule can alter its integrin binding affinity. This means that in principle, every functionalized compound for both in vitro and in vivo applications should be tested individually to obtain comparable results. It is important to mention here that e.g. the introduction of a PEG spacer does not guarantee better ligands properties (solubility, affinity). Peg is not always extended in aqueous solution and thus the distance between the biomolecule and the functional unit is not defined99. Changes in affinity induced by a spacer and a functional unit are hard to predict. Additionally, functionalization of bioactive compounds can also strongly alter the pharmacodynamics, e.g. the total uptake and distribution of the compound in the organs after its intake. Mostly, this is observable because of a big change in lipophilicity due to the different modifications. Especially for molecular imaging, where only defined structures in the body should be visualized, it is important to evaluate and optimize the effect of every modification (e.g. different spacer, chelator, coordinating metal) in this regard. Important points to be addressed regarding the applicability of the probes in standard procedures of diagnosis are the simplicity of production and the flexibility in the type of tracer that can be introduced. In the case of functionalization for surface coating, the strength and stability of the binding to the surface by the anchoring unit and the length and chemical structure of the spacer for a defined purpose (e.g. cell adhesion) has to be taken into account.

Molecules used as negative control in the determination of binding activities

For cellular and in vitro experiments, molecules with comparable steric properties and lipophilicity but without biological activity often serve as control compounds. Targeted substitution of any of the three amino acids in the RGD-sequence leads to inactivation of the ligand. A substitution of glycine by alanine leads to steric repulsions on the binding groove between the α- and β-subunit. Moreover, any elongation of the ligand (e.g. glycine to β-alanine and aspartate to glutamate substitution) leads to complete loss of binding activity. The molecules can be functionalized in the same way as their active biologically active counterparts (e.g. via lysine side chain). For this study, linear and cyclic control molecules have been synthesized and evaluated.

Conclusion

After the initial discovery of the RGD sequence in fibronectin, a large number of integrin ligands, binding to RGD-recognizing integrins, were developed by many groups around the world and became highly important for medical applications and for biophysical studies. For the development of each of these compounds, different evaluation techniques (e.g. various cel-based and cell free methods) have been used, allowing a good comparison and selection process of the compounds within a study. However, comparing the values determined by different groups for the very same compound shows very high deviations. For this reason we evaluated for the first time the most frequently used compounds in a homogenous solid phase binding assay for their binding affinity to six RGD-binding integrins (αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ8, α5β1, αIIbβ3). This gives the possibility to choose the ligand with the ideal affinity and selectivity pattern for a given application and opens new doors for the application of those ligands. However, the complex mechanism including several steps of conformational transitions in which the initial ligand binding to the resting state of the integrin and the stronger binding in the focal adhesion, might have consequences for the IC50-value given here with data under different environmental condition in vivo102.

Methods Section

Integrin Binding Assay

The activity and selectivity of integrin ligands were determined by a solid-phase binding assay according to the previously reported protocol103 using coated extracellular matrix proteins and soluble integrins. The following compounds were used as internal standards: Cilengitide, c(RGDf(NMe)V) (αvβ3–0.54 nM, αvβ5–8 nM, α5β1–15.4 nM), linear peptide RTDLDSLRT4 (αvβ6–33 nM; αvβ8–100 nM) and tirofiban5 (αIIbβ3–1.2 nM).

Flat-bottom 96-well ELISA plates (BRAND, Wertheim, Germany) were coated overnight at 4 °C with the ECM-protein (1) (100 μL per well) in carbonate buffer (15 mM Na2CO3, 35 mM NaHCO3, pH 9.6). Each well was then washed with PBS-T-buffer (phosphate-buffered saline/Tween20, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, 0.01% Tween20, pH 7.4; 3 × 200 μL) and blocked for 1 h at room temperature with TS-B-buffer (Tris-saline/BSA buffer; 150 μL/well; 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, pH 7.5, 1% BSA). In the meantime, a dilution series of the compound and internal standard is prepared in an extra plate, starting from 20 μM to 6.4 nM in 1:5 dilution steps. After washing the assay plate three times with PBS-T (200 μL), 50 ul of the dilution series were transfered to each well from B–G. Well A was filled with 100 ul TSB-solution (blank) and well H was filled with 50 ul TS-B-buffer. 50 ul of a solution of human integrin (2) in TS-B-buffer was transfered to wells H–B and incubated for 1 h at rt. The plate was washed three times with PBS-T buffer, and then primary antibody (3) (100 μL per well) was added to the plate. After incubation for 1 h at rt, the plate was washed three times with PBS-T. Then, secondary peroxidase-labeled antibody (4) (100 μL/well) was added to the plate and incubated for 1 h at rt. After washing the plate three times with PBS-T, the plate was developed by quick addition of SeramunBlau (50 μL per well, Seramun Diagnostic GmbH, Heidesee, Germany) and incubated for 5 min at rt in the dark. The reaction was stopped with 3 M H2SO4 (50 μL/well), and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a plate reader (POLARstar Galaxy, BMG Labtechnologies). The IC50 of each compound was tested in duplicate, and the resulting inhibition curves were analyzed using OriginPro 7.5G software. The inflection point describes the IC50 value. All determined IC50 were referenced to the activity of the internal standard.

αvβ3

1.0 μg/mL human vitronectin; Millipore.

2.0 μg/mL, human αvβ3-integrin, R&D.

2.0 μg/mL, mouse anti-human CD51/61, BD Biosciences.

1.0 μg/mL, anti-mouse IgG-POD, Sigma-Aldrich.

α5β1

0.5 μg/mL; human fibronectin, Sigma-Aldrich.

2.0 μg/mL, human α5β1-integrin, R&D.

1.0 μg/mL, mouse anti-human CD49e, BD Biosciences.

2.0 μg/mL, anti-mouse IgG-POD, Sigma-Aldrich.

αvβ5

5.0 μg/mL; human vitronectin, Millipore.

3.0 μg/mL, human αvβ5-integrin, Millipore.

1:500 dilution, anti-αv mouse anti-human MAB1978, Millipore.

1.0 μg/mL, anti-mouse IgG-POD, Sigma-Aldrich.

αvβ6

0.4 μg/mL; LAP (TGF-β), R&D.

0.5 μg/mL, human αvβ6-Integrin, R&D.

1:500 dilution, anti-αv mouse anti-human MAB1978, Millipore.

2.0 μg/mL, anti-mouse IgG-POD, Sigma-Aldrich.

αvβ8

0.4 μg/mL; LAP (TGF-b), R&D.

0.5 μg/mL, human αvβ8-Integrin, R&D.

1:500 dilution, anti-αv mouse antihuman MAB1978, Millipore.

2.0 μg/mL, anti-mouse IgG-POD, Sigma-Aldrich.

αIIbβ3

10.0 μg/mL; human fibrinogen, Sigma-Aldrich.

5.0 μg/mL, human platelet integrin αIIbβ3, VWR.

2.0 μg/mL, mouse anti-human CD41b, BD Biosciences.

1.0 μg/mL, anti-mouse IgG-POD, Sigma-Aldrich.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kapp, T. G. et al. A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Activity and Selectivity Profile of Ligands for RGD-binding Integrins. Sci. Rep. 7, 39805; doi: 10.1038/srep39805 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the company GE for providing us with samples of Fluciclatide andNC100717, the company 3B Pharmaceuticals for samples of JSM6427 and Prof. Corti and Dr. Curnis for providing us with a sample of A20FMDV2.TGK acknowledges the International Graduate School for Science and Engineering (IGSSE) of the Technische Universität München (TUM) for financial support. BG is the Erwin Neter Professor in cell and Tumor Biology. HK is Carl von Linde Professor at the Institute for Advanced Study. Financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Center of Integrated Protein Science Munich (CIPSM) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Author Contributions T.G.K., R.Z., C.M.-M., B.G., J.S. and H.K. wrote the manuscript, T.G.K., F.R. and O.V.M. performed the experiments, T.G.K., F.R., S.N., O.V.M., A.E.C.-A., U.R., J.N., C.M.-M., H.-J.W. and H.K. analyzed the data, T.G.K., F.R., J.S., B.G. and H.K. designed the study, all authors read and revised the manuscript.

References

- Hynes R. O. & Naba A. Overview of the matrisome - an inventory of extracellular matrix constituents and functions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 4, a004903 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz C., Stewart K. M. & Weaver V. M. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 123, 4195–4200 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano R. L. Signal transduction by cell adhesion receptors and the cytoskeleton: functions of integrins, cadherins, selectins, and immunoglobulin-superfamily members. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 42, 283–323 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B., Spatz J. P. & Bershadsky A. D. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 21–33 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierschbacher M. D. & Ruoslahti E. Cell attachment activity of fibronectin can be duplicated by small synthetic fragments of the molecule. Nature 309, 30–33 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A., Auernheimer J., Modlinger A. & Kessler H. Targeting RGD Recognizing Integrins: Drug Development, Biomaterial Research, Tumor Imaging and Targeting. Curr. Pharmaceutical Design 12 2723–2747 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrake H. M. & Patterson L. H. Strategies To Inhibit Tumor Associated Integrin Receptors: Rationale for Dual and Multi-Antagonists, J. Med. Chem. 57, 6301–6315 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auzzas L. et al. Targeting alphavbeta3 integrin: design and applications of mono- and multifunctional RGD-based peptides and semipeptides. Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 1255–1299 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimaoka M. & Springer T. A. Therapeutic antagonists and conformational regulation of integrin function. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2, 703–716 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plow E. F., Haas T. A., Zhang L., Loftus J. & Smith J. W. Ligand Binding to Integrins, J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21785–21788 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada Y., Ye X. & Simon S. The integrins. Genome Biology 8, 215 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mould A. P. & Humphries M. J. Cell biology - adhesion articulated. Nature 432, 27–28 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelli U. K., Rechenmacher F., Ali Sobahi T. R., Mas-Moruno C. & Kessler H. Tumor targeting via integrin ligands, Front. Oncol. 3, 222 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D., Brennan M. & Moran N. Integrins as therapeutic targets: lessons and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 9, 804–820 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K., Rivera-Nieves J., Sandborn W. J. & Shattil S. Integrin-based therapeutics: biological basis, clinical use and new drugs biological basis, clinical use and new drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 173–183 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. L. & Picard M. Integrins as therapeutic targets. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 33, 405–412 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp T. G., Rechenmacher F., Sobahi T. R. & Kessler H. Integrin modulators: a patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 23, 1273–1295 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degrosellier J. S. & Cheresh D. A. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 9–22 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A. M. et al. Nanoparticles coated with the tumor-penetrating peptide iRGD reduce experimental breast cancer metastasis in the brain. J. Mol. Med. 93, 991–1001 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottelius M., Laufer B., Kessler H. & Wester H.-J. Ligands for mapping αvβ3-integrin expression in vivo. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 969–980 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikov S. V., Pasapera A. M., Sabass B. & Waterman C. M. Force fluctuations within focal adhesions mediate ECM-rigidity sensing to guide directed cell migration. Cell 151, 1513–27 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersel U., Dahmen C. & Kessler H. RGD modified polymers: biomaterials for stimulated cell adhesion and beyond. Biomaterials 24, 4385–4415 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold M. et al. Activation of Integrin Function by Nanopatterned Adhesive Interfaces. ChemPhysChem 3, 383–388 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Moruno C. et al. αvβ3- or α5β1-Integrin-Selective Peptidomimetics for Surface Coating. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 7048–7067 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff M. et al. Selective recognition of cyclic RGD peptides of NMR defined conformation by alpha IIb beta 3, alpha V beta 3, and alpha 5 beta 1 integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20233–20238 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley M. et al. Arg-Gly-Asp constrained within cyclic pentapeptides. Strong and selective inhibitors of cell adhesion to vitronectin and laminin fragment P1. FEBS Lett. 291, 50–54 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler H., Gratias R., Hessler G., Gurrath M. & Müller G. Conformation of cyclic peptides. Principle concepts and the design of selectivity and superactivity in bioative sequences by ‘spatial screening. Pure & Appl. Chem. 68, 1201–1205 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Weide T., Modlinger A. & Kessler H. Spatial Screening for the Identification of the Bioactive Conformation of Integrin Ligands; Topics in Current Chemistry 272, 1–50 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Müller G., Gurrath M. & Kessler H. Pharmacophore refinement of gpIIb/IIIa antagonists based on comparative studies of antiadhesive cyclic and acyclic RGD peptides; J. Comp-Aided Mol. Design 8, 709–730 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechantsreiter M. A. et al. N-Methylated cyclic RGD peptides as highly active and selective alpha(V)beta(3) integrin antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 42, 3033–3040 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Moruno C., Rechenmacher F. & Kessler H. Cilengitide: the first anti-angiogenic small molecule drug candidate design, synthesis and clinical evaluation. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 10, 753–768 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. et al. Structure of a complete integrin ectodomain in a physiologic resting state and activation and deactivation by applied forces. Mol. Cell 32, 849–861 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J. P. et al. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alphavbeta3. Science 294, 339–345 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelli U. K. et al. The Solution Conformation of Cilengitide Represents the Receptor Bound Conformation better than the X-Ray Structure of Cilengitide, Chemistry Eur. J. 20, 14201–14206 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann D. et al. Probing Integrin Selectivity: Rational Design of Highly Active and Selective Ligands for the a5b1 and avb3 Integrin Receptor. Angew. Chem. 119, 3641–3644 (2007). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 3571–3574 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stragies R. et al. Design and synthesis of a new class of selective integrin alpha5beta1 antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 50, 3786–3794 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer S. et al. Pharmacophoric Modifications Lead to Superpotent αvβ3 Integrin Ligands with Suppressed α5β1 Activity; J. Med. Chem. 57, 3410–3417 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltsev O. V. et al. Stable Peptides Instead of Stapled Peptides: Highly Potent αvβ6-Selective Integrin Ligands, Angew. Chem. 128, 1559-1563 (2016). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 1535–1538 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechenmacher F. et al. Functionalizing αvβ3- or α5β1-selective integrin antagonists for surface coating: a method to discriminate integrin subtypes in vitro. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 1572–1575 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechenmacher F. et al. A molecular toolkit for the functionalization of titanium-based biomaterials that selectively control integrin-mediated cell adhesion. Chemistry 19, 9218–9223 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J. P. et al. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha Vbeta3 in complex with an Arg–Gly–Asp ligand. Science 296, 151–155 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli L. et al. Ligand Binding Analysis for Human α5β1 Integrin: Strategies for Designing New α5β1 Integrin Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 48, 4204–4207 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli L., Lavecchia A., Gottschalk K. E., Novellino E. & Kessler H. Docking Studies on αvβ3 Integrin Ligands: Pharmacophore Refinement and Implications for Drug Design; J. Med. Chem. 46, 4393–4404 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann D. et al. Breaking the dogma of the metal-coordinating carboxylate group in integrin ligands: introducing hydroxamic acids to the MIDAS to tune potency and selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 4436–4440 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagae M. et al. Crystal structure of α5β1 integrin ectodomain: atomic details of the fibronectin receptor. J. Cell Biol. 187, 131–140 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp T. G., Fottner M., Maltsev O. V. & Kessler H. Small Cause, Great Impact: Modification of the Guanidine Group in the RGD Motif Controls Integrin Subtype Selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 1540–1543 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margadant C. & Sonnenberg A. Integrin–TGF‐β crosstalk in fibrosis, cancer and wound healing, EMBO reports 11, 97–105 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander M. et al. Definition of two angiogenic pathways by distinct alpha v integrins. Science 270, 1500–1502 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. L., Hölzemann G., Sulyok G. A. & Kessler H. Nanomolar small molecule inhibitors for alphav(beta)6, alphav(beta)5, and alphav(beta)3 integrins. J. Med. Chem. 45, 1045–1051 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Moruno C. et al. Increasing αvβ3 selectivity of the anti-angiogenic drug cilengitide by N-methylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 9496–9500 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assa-Munt N., Jia X., Laakkonen P. & Ruoslahti E. Solution Structures and Integrin Binding Activities of an RGD Peptide with Two Isomers. Biochemistry 40, 2373–2378 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochen A. et al. Biselectivity of isoDGR peptides for fibronectin binding integrin subtypes α5β1 and αvβ6: conformational control through flanking amino acids. J. Med. Chem. 56, 1509–1519 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire J. J., Kuc R. E. & Davenport A. P. Radioligand binding assays and their analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 897, 31–77 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa S. A. & Mohamed S. Human alphavbeta3 integrin potency and specificity of TA138 and its DOTA conjugated form (89)Y-TA138. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 45, 109–113 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. et al. PET Imaging of Integrin Positive Tumors Using F Labeled Knottin Peptides. Theranostics 1, 403–412 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier A. et al. Endothelial alpha5 and alphav integrins cooperate in remodeling of the vasculature during development. Development 137, 2439–2449 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A. O. et al. Conformational Control of Integrin-Subtype Selectivity in isoDGR Peptide Motifs: A Biological Switch. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 9278–9281 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Z. R., Gould R. J., Jacobs J. W., Friedman P. A. & Polokoff M. A. Echistatin – A potent platelet aggregation inhibitor from the venom of the viper, Echis Carinatus. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 19827–19832 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff M., McLane M. A., Beviglia L., Niewiarowski S. & Timpl R. Comparison of Disintegrins with limited variation in the RGD Loop in their binding to purified integrins aIIbb3, avb3 and a5b1 and in cell adhesion inhibition. Cell Adhes. Commun. 2, 491–501 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Ji S., Tomaselli E., Yang Y. & Liu S. Comparison of biological properties of (111)In-labeled dimeric cyclic RGD peptides. Nucl. Med. Biol. 42, 137–45 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkan K. et al. A heterodimeric [RGD-Glu-[(64)Cu-NO2A]-6-Ahx-RM2] αvβ3/GRPr-targeting antagonist radiotracer for PET imaging of prostate tumors. Nucl. Med. Biol. 41, 133–139 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pytela R., Pierschbacher M. D., Ginsberg M. H., Plow E. F. & Ruoslahti E. Platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb/IIIa: member of a family of Arg-Gly-Asp–specific adhesion receptors. Science 231, 1559–1562 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogford J. E., Davis G. E. & Meininger G. A. RGDN Peptide Interaction with Endothelial a5b1 Integrin Causes Sustained Endothelin-dependent Vasoconstriction of Rat Skeletal Muscle Arterioles, J. Clin. Invest. 100, 1647–1653 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedhar S., Ruoslahti E. & Pierschbacher M. D. A Cell Surface Receptor Complex for Collagen Type I Recognizes the Arg-Gly-Asp Sequence. J. Cell. Biol. 104, 585–593 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanowich-Knipp S. J., Chakrabarti S., Siahaan T. J., Williams T. D. & Dillman R. K. Solution stability of linear vs. cyclic RGD peptides. J. Pep. Res. 53, 530–541 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee J. et al. Multiple N-Methylation by a Designed Approach Enhances Receptor Selectivity. J. Med. Chem. 50, 5878–5881 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler H. Conformation and Biological Activity of Cyclic Peptides; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 21, 512–523 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Haubner R., Gratias R., Diefenbach B., Goodman S. L., Jonczyk A. & Kessler H. Structural and Functional Aspects of RGD-Containing Cyclic Pentapeptides as Highly Potent and Selective Integrin αvβ3 Antagonists. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 7461–7472 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Haubner R., Finsinger D. & Kessler H. Stereoisomeric Peptide Libraries and Peptidomimetics for Designing Selective Inhibitors of the αvβ3 Integrin for a New Cancer Therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 36, 1374–1389 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Becker A. et al. Metabolism and Disposition of the av-Integrin β3/β5 Receptor Antagonist Cilengitide, a Cyclic Polypeptide, in Humans. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 55, 815–824 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupp R. et al. Cilengitide combined with standard treatment for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter (CENTRIC EORTC 26071–22072 study): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 15, 1100–1108 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabors L. B. et al. Two cilengitide regimens in combination with standard treatment for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma and unmethylated MGMT gene promoter: results of the open-label, controlled,randomized phase II CORE study. Neuro Oncol. 17, 708–715 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci M. et al. Cilengitide restrains the osteoclast-like bone resorbing activity of myeloma plasma cells. Brit. J. Haematol. 173, 59–69 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewan C. & March J. Patent PCT/GB2015/053215.

- Alva A. et al. Phase II study of Cilengitide (EMD 121974, NSC 707544) in patients with non-metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer, NCI-6735. A study by the DOD/PCF prostate cancer clinical trials consortium. Invest. New Drugs 30, 749–757 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantlehner M. et al. Selective RGD-Mediated Adhesion of Osteoblasts at Surfaces of Implants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 560–562 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantlehner M. et al. Surface Coating with Cyclic RGD Peptides Stimulates Osteoblast Adhesion and Proliferation as well as Bone Formation. ChemBioChem 1, 107–114 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Rodriguez V. et al. Preparation and preclinical evaluation of (66)Ga-DOTA-E(c(RGDfK))2 as a potential theranostic radiopharmaceutical. Nucl Med Biol. 42, 109–114 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garanger E., Boturyn D. & Dumy P. Tumor targeting with RGD peptide ligands-design of new molecular conjugates for imaging and therapy of cancers. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 7, 552–558 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks P. C. et al. Integrin alpha v beta 3 antagonists promote tumor regression by inducing apoptosis of angiogenic blood vessels. Cell 79, 1157–1164 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prante O. et al. 3,4,6-Tri-O-acetyl-2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoroglucopyranosyl phenylthiosulfonate: a thiol-reactive agent for the chemoselective 18F-glycosylation of peptides. Bioconjugat. Chem. 18, 254 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivunen E., Wang B. & Ruoslahti E. Phage Libraries Displaying Cyclic Peptides with Different Ring Sizes: Ligand Specificities of the RGD-Directed Integrins Nature Biotechnology 13, 265–270 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolarczyk R. et al. Antitumor effect of RGD-4C-GG-D(KLAKLAK)2 peptide in mouse B16(F10) melanoma model. Acta Biochim. Pol. 53, 801–805 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölig P. et al. Novel RGD lipopeptides for the targeting of liposomes to integrin-expressing endothelial and melanoma cells. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 17, 433–441 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indrevoll A. et al. NC-100717: A versatile RGD peptide scaffold for angiogenesis imaging. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 6190–6193 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny L. M. et al. Phase I Trial of the Positron-Emitting Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) Peptide Radioligand 18F-AH111585 in Breast Cancer Patients. J. Nucl. Med. 49, 879–886 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi M. V., Laurence J. S. & Siahaan T. J. The role of thiols and disulfides in protein chemical and physical stability. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci 10, 614–625 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curnis F. et al. Spontaneous formation of l-isoaspartate and gain of function in fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36466–36476 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S. et al. The RGD motif in fibronectin is essential for development but dispensable for fibril assembly. J. Cell Biol. 178, 167–178 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeltzing O. et al. Inhibition of integrin alpha5beta1 function with a small peptide (ATN-161) plus continuous 5-FU infusion reduces colorectal liver metastases and improves survival in mice. Int. J. Cancer 104, 496–503 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann D. et al. Rational Design of Highly Active and Selective Ligands for the α5β1 Integrin Receptor. ChemBioChem 9, 1397–1407 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer S. et al. Selective imaging of the angiogenic relevant integrins α5β1 and αvβ3. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 11656–11659 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft S. et al. Definition of an unexpected ligand recognition motif for alphav beta6 integrin. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 1979–1985 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCara D. et al. Structure-Function Analysis of Arg-Gly-Asp Helix Motifs in αvβ6 Integrin Ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9657–9665 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough R. M., Naughton M. A., Teng W. et al. Design of potent and specific integrin antagonists. Peptide antagonists with high specificity for glycoprotein IIb-IIIa. J Biol Chem 268, 1066–73 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman G. D. et al. Non-peptide fibrinogen receptor antagonists. Discovery and design of exosite inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 35, 4640–4642 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldred C. D. et al. Orally active non-peptide fibrinogen receptor (GpIIb/IIIa) antagonists: identification of 4-[4-[4-(aminoiminomethyl)phenyl]-1-piperazinyl]-1-piperidineacetic acid as a long-acting, broad spectrum antithrombotic agent. J. Med. Chem. 37, 3882–3885 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liese S. & Netz R. R. Influence of length and flexibility of spacers on the binding affinity of divalent ligands. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 11, 804–816 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallarola D. et al. Interface Immobilization Chemistry of cRGD-based Peptides Regulates Integrin Mediated Cell Adhesion. Adv. Funct. Mat. 24, 943–956 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubner R. et al. Noninvasive Visualization of the Activated αvβ3 Integrin in Cancer Patients by Positron Emission Tomography and [18F]Galacto-RGD. PLoS Medicine 2, 244–252 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šimeček J. et al. Benefits of NOPO As Chelator in Gallium-68 Peptides, Exemplified by Preclinical Characterization of 68Ga-NOPO-c(RGDfK). Mol. Pharm. 11, 1687‒1695 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. A. et al. The glycophorin A transmembrane sequence within integrin αvß3 creates a non-signalling integrin with low basal affinity that is strongly adhesive under force. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 2988–3006 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A. O., Otto E., Mas-Moruno C., Schiller H. B., Marinelli L., Cosconati S., Bochen A., Vossmeyer D., Zahn G., Stragies R., Novellino E. & Kessler H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9278−9281. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.