Abstract

Background

Erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESAs) were proposed to enhance survival of renal tissues through direct effects via activation of EPO receptors on renal cells resulting in reduced cell apoptosis, or indirect effects via increased oxygen delivery due to increased numbers of Hb containing red blood cells. Thus through several mechanisms there may be benefit of ESA administration on kidney disease progression and kidney function in renal patients. However conflicting ESA reno-protection outcomes have been reported in both pre-clinical animal studies and human clinical trials. To better understand the potential beneficial effects of ESAs on renal-patients, meta-analyses of clinical trials is needed.

Methods

Literature searches and manual searches of references lists from published studies were performed. Controlled trials that included ESA treatment on renal patients with relevant renal endpoints were selected.

Results

Thirty two ESA controlled trials in 3 categories of intervention were identified. These included 7 trials with patients who had a high likelihood of AKI, 7 trials with kidney transplant patients and 18 anemia correction trials with chronic kidney disease (predialysis) patients. There was a trend toward improvement in renal outcomes in the ESA treated arm of AKI and transplant trials, but none reached statistical significance. In 12 of the anemia correction trials, meta-analyses showed no difference in renal outcomes with the anemia correction but both arms received some ESA treatment making it difficult to assess effects of ESA treatment alone. However, in 6 trials the low Hb arm received no ESAs and meta-analysis also showed no difference in renal outcomes, consistent with no benefit of ESA/ Hb increase.

Conclusions

Most ESA trials were small with modest event rates. While trends tended to favor the ESA treatment arm, these meta-analyses showed no reduction of incidence of AKI, no reduction in DGF or improvement in 1-year graft survival after renal transplantation and no significant delay in progression of CKD. These results do not support significant clinical reno-protection by ESAs.

Keywords: AKI (acute kidney injury), Anemia, Clinical trial, EPO, Erythropoietin, ESA, Meta-analysis, Progression of CKD, Reno-protection, Tissue protection, Transplant

Background

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a circulating hormone produced by the kidney, that stimulates erythropoiesis by binding and activating the EPO receptors (EPOR) on erythroid progenitor cells [1]. Subjects with chronic kidney disease (CKD) often develop anemia because of decreased production of EPO resulting in insufficient erythropoiesis. The cloning of the EPO gene allowed treatment of anemia in CKD patients by stimulating erythropoiesis with rHuEpo or other erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESAs) [2].

Chronic anemia can result in organ damage affecting the cardiovascular system, kidneys, and the central nervous system [3–6] thus anemia correction might improve outcomes. In addition, EPOR was reported in nonhematopoietic tissues including renal cells [1], with some preclinical data suggesting that ESAs may be reno-protective due activation of EPOR resulting in anti-apoptotic effects [7, 8]. Some data suggest ESAs are reno-protective through an EpoR:CD131 complex and that EPO derivatives lacking erythropoietic activity are still reno-protective [9]. Other data conflicts with both hypotheses [1, 10]. However, the possibility ESAs might mitigate the serious consequences of renal ischemia through direct (anti-apoptosis of renal cells) or indirect effects (increased oxygen delivery with increased Hb) resulted in clinical trials to assess the potential benefit of ESA treatment in humans with renal diseases, and analysis of the results of those trials is warranted.

Clinical interventions to see if there is a relationship between ESAs and renal outcomes included short-term prophylactic ESA treatment where there was a high likelihood of acute kidney injury (AKI), e.g., patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery. In another modality, ESA treatment at the time of surgery might mitigate the ischemic damage and delayed graft function (DGF) that occurs during the perioperative period following kidney transplant. DGF increases the risk of acute rejection, impaired graft function, and reduces long term patient and graft survival. In a third modality, treatment of CKD patients to correct anemia associated with renal failure presumes that ESA treatment might delay or prevent renal disease progression through direct anti-apoptotic effects on renal cells or indirect effects of anemia correction, eg improved oxygen delivery.

Most of the trials examining the effect of ESAs on renal patients were small, outcomes were not robust or they varied across studies. Therefore, results from individual trials were inconclusive, but meta-analyses of results from those clinical trials may allow more definitive conclusions. We reasoned further that meta-analysis of multiple modalities would add additional value. The three modalities above were selected for meta-analysis because they examined direct and/or indirect effects of ESAs on renal disease progression or renal function. We report here that meta-analyses show no significant beneficial effects in any of the modalities, suggesting that ESAs have little reno-protective benefits, at least with the patient populations examined and clinical designs employed.

Methods

We wished to assess the effect of ESAs on kidneys by analyzing data from human clinical trials where ESAs might mitigate effects of ischemia or disease progression. This necessitated comprehensive searches and identification and analysis of controlled trials with renal patients where ESAs were used to protect kidneys from ischemia or to slow renal disease progression. All trials that had relevant renal endpoints were selected and analyzed, and data was extracted from those that might test the hypothesis.

Search strategy

Literature searches were performed using OVIDSP (Wolters Kluwer companies) to access MEDLINE and other databases including Current contents, Embase and BIOSYS previews, using search terms for ESAs (EPO, erythropoietin, rHuEpo, rEpo, epoetin, darbepoetin) in combination with anemia terms (anemia, Hb, hemoglobin, hct, hematocrit), kidney or kidney injury (renal, kidney, transplant, CKD, chronic kidney disease, delayed graft function, DGF, acute kidney injury, and AKI), and terms describing possible beneficial outcome (protect, protection, reno-protection). Searches of the Clinicaltrials.gov and the Cochran database websites were performed using ESA terms combined with anemia, renal, kidney and transplant, to further identify potential papers of interest. A manual search of the reference lists in papers, review articles and other meta-analyses identified additional papers.

Trial selection/inclusion criteria

Papers considered for inclusion described human clinical data with ESA treatment and renal endpoints. Papers were rejected if they were not controlled trials, were case reports, described only preclinical data, or lacked the relevant renal endpoints. Papers with ESA treatment of renal patients on dialysis were omitted because renal disease progression was not applicable. The final list included controlled clinical trials that utilized ESAs in transplantation, AKI, and for anemia correction in predialysis CKD patients.

Data extraction

The data was recovered by SE and reviewed by ZE. Recovered data included the study characteristics, study location, length of study, ESA treatment, nature of the comparator arm, number of subjects in each arm, time intervals and definitions of renal endpoints. Results were grouped according to study type (patients presenting with or at risk of AKI, studies with kidney transplant patients, and CKD patients undergoing anemia correction). For trials involving AKI, data collected for meta-analysis was the number of patients with AKI and number of patients with renal recovery following AKI. Other endpoints recovered from those trials were any creatinine-based or enzymatic markers that were measures of renal function or renal injury. With kidney transplant studies the measures recovered for meta-analysis were incidence of DGF within the first week post-surgery and graft loss/survival over a 1 year period. Other data collected were any creatinine-based data, incidence of proteinuria, and enzymatic-based markers of renal injury. The meta-analysis endpoint in anemia correction trials was incidence of progression to renal replacement therapy (RRT; progression to dialysis or kidney transplant) at any time during the study. Other data recovered were, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), serum creatinine (sCr), and their rate of change over time, and incidence of proteinuria. All the trial information and secondary measures are summarized in Tables 2, 3 and 4. The data used in meta-analysis are shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Table 2.

AKI studies

| Reference | Study Location | Patient Population | ESA | Control | Subjects (Total and # in groups) | Renal Injury (AKI) Definition | Other Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dardashti 2014 [24] | Sweden (Skåne University Hospital, Lund) | Patients scheduled for CABG with preexisting renal impairment | Epoetin zeta (400 IU/kg; Retacrit®) administered preoperative | Equivalent volume of saline | N = 70: ESA(35), control(35) | RIFLE on d3 based on eGFR using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula | No difference in Hb, transfusions, relative cystatin C, NGAL, creatinine, urea, or eGFR) |

| deSeigneux 2012 [76] | Switzerland (University Hospital, Geneva) | Patients admitted to the ICU for cardiac surgery | ESA Group 1 (20,000 IU; epoetin α), group 2 (40,000 UI epoetin α) & group 3 (control) 1 to 4 h post-surgery | Isotonic sodium chloride | N = 80: ESA group 1(20), ESA group 2(20), control(40) | AKIN from ICU admission to the following wk | No difference in Hb, creatinine, cystatin c, or urinary NGAL levels |

| Endre 2010 [26] | New Zealand (Christchurch or Dunedin Hospital) | Patients admitted to the ICU or high-risk patients scheduled for cardiothoracic surgery with CPB | ESA (500 U/kg (iv) to a maximum of 50,000 U), within 6 h of increased GGT AP and a second dose 2 h later | Equivalent volume of normal saline | N = 163: ESA(84), control(78) | AKIN classification in 7 days | No difference in any creatinine-based variables |

| Kim 2013 [27] | Korea (Yonsei University Health System, Seoul) | Patients with preoperative risk factors for AKI who were scheduled for complex valvular heart operations | Epoetin α (300 IU/kg (iv); Epocain) after anesthetic induction | Equivalent volume of normal saline. | N = 98: ESA(49), control(49) | An increase in serum creatinine >0.3 mg/dl or >50% from baseline: | No differences in Hb, sCr, eGFR, creatinine clearance, cystatin C or serum NGAL |

| Olweny 2012 [21] | USA (UT Southwestern, Houston, Texas) | Patients who underwent laparoscopic partial nephrectomy | Epoetin α (500 IU/kg (iv) Procrit) 30 min prior to LPN | No ESA | N = 106: ESA(52), control(54). | NA | No difference in eGFR |

| Oh 2012 [16] | Korea, National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul | Patients scheduled for elective CABG | Epoetin β (300 U/kg Recormon) before CABG | Saline | N = 71: ESA(36,) control(35). | SCr ≥ 0.3 mg/dL from baseline, ≥50% increase in the sCr concentration in the first 72 h after CABG, or <0.5 mL/kg per hour of oliguria for more than six hr | sCr was not different from baseline in the ESA group, but was higher in the placebo group. |

| Park 2005 [20] | USA (surgical ICU), cardiothoracic ICU, or medical ICU at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St Louis, Missouri) | Patients scheduled for elective CABG | ESA (112 U/kg/week average) within the first 14 days of RRT initiation | No ESA | N = 187; ESA(71), control(116) | NA | No difference in transfusions. sCr at 2 weeks favored the ESA arm but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.054). No difference in renal recovery or renal survival |

| Tasanarong 2013 [28] | Thailand (Thammasat Chalerm Prakiat Hospital) | Patients scheduled for elective CABG using CPB | epoetin β (200 U/kg; Recormon) 3 d before CABG and 100 U/kg at the operation time. | Same volume & schedule of 0.9% saline | N = 100: ESA(50), control(50) | ≥0.3 mg/dl or ≥50% increase in sCr from baseline within the first 48 h post-operation according to the KDIGO 2012 criteria. | No difference in Hb. sCr increase and eGFR decrease was lower in the ESA group. Mean urine NGAL group was lower in the ESA group 2 h & 18 h. |

| Yoo 2011 [29] | Korea (Yonsei University Health System, Seoul) | Patients scheduled for valvular heart surgery (VHS) with preoperative anemia | Epoetin α (500 IU/kg (iv); Epocain and 200 mg iron sucrose (iv)) 16-24 h pre-surgery | Equivalent volume of normal saline | N = 74: ESA(37), control(37) | Increased sCr of 0.3 mg/dl, or 50–200% from baseline, using modified RIFLE classification within 48 h after surgery | Reduced transfusions. No difference in mortality |

Table 3.

Kidney transplant studies

| Reference | Study Location | ESA | Control | Subjects (Total and # in groups) | DGF definition | Other Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aydin 2012 [31] | Netherlands (Leiden University Medical Center) | Epoetin β (33,000 IU) on 3 consecutive d, starting 3–4 h before transplantation & 24 & 48 h post-reperfusion. | Saline solution (0.9%) | N = 92: ESA(45), control(47) | Need for dialysis in the first wk or if sCr increased, remained unchanged or decreased by less than 10% per d during 3 consecutive d for more than 1 week | No significant differences in Hb, endogenous creatinine clearance or proteinuria |

| Coupes 2015 [30] | United Kingdom (Manchester Royal Infirmary) | Epoetin β (100,000 U; 33,000 intraoperative and 33,000 at 24 and 48 h). | Placebo (not disclosed) | N = 39: ESA(19), control (20) | Need for dialysis in first 7 days post-transplant | No difference in Hb or number of transfusions. No significant difference in sCr or eGFR at any time point to 90 day, No difference in acute rejection episodes, or biomarkers (NGAL, KIM-1 or IL-18) |

| Hafer 2012 [32] | Germany (Hannover Medical School) | Epoetin α (40,000 U (iv); Eprex) immediately before reperfusion and d3 and d7 after transplantation | Placebo (not disclosed) same volume and appearance | N = 88: ESA (44), control (44) | Urine output of less than 500 ml in the first 24 h after transplantation and/or need of dialysis because of graft dysfunction within the first wk after transplantation | Higher Hb at 2 and 4 but not 6 weeks. No significant difference in transfusions, eGFR 6 weeks or 12 months. No significant differences 6 weeks and 6 months post-transplant in histological indices. |

| Kamar 2010 [23] | France (Department of Nephrology, Dialysis and Organ Transplantation, CHU Rangueil, Toulouse) | Epoetin α or epoetin β (250 IU/kg/week) on d5 post-transplant, unless Hb level was above 12 g/dl for women and 13 g/dl for men. Cumulative ESA dose (D30) was 727 ± 499 IU/kg. | No ESA during the first month post-transplantation unless Hb dropped to <8 g/dl) | N = 181: ESA (82), control (99) | NA | Reduced Hb in ESA arm. No difference in transfusions. sCr levels were similar in both groups at 3, 6 and 12 months post-transplantation |

| Martinez, 2010 [33] | France (13 centers) | Epoetin β (30.000 IU; Neorecormon) given before surgery and at 12 h, d7 and d14 | No ESA during the first month post transplantation | N = 104: ESA (51), control (53) | The need for dialysis during the first wk after transplantation | Higher Hb in ESA arm at 1 month. No difference in transfusions. No difference in sCr at any time point. No difference in eGFR at 1 or 3 months |

| Sureshkumar 2012 [34] | Pennsylvania (USA) (Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) | Epoetin α (100,000 U (iv); Procrit) intraarterially immediately after reperfusion | Matched placebo (not disclosed) | N = 72: ESA (36), control (36) | The need for dialysis within the first wk of transplantation | No difference in Hb, sCr, eGFR or urinary biomarkers of AKI (NGAL or IL-18) |

| Van Biesen 2005 [35] | Belgium (University Hospital Ghent) | Epoetin β (100/IU/kg; Recormon) immediately after transplantation then thrice weekly to maintain Hb above 12 g/dL | No ESA | N = 26: ESA (14), control (12) | Not defined | Shorter time to target Hb in ESA arm. No difference in transfusions or sCr at 3 months |

| Van Loo 1996 [36] | Belgium (University Hospital, Gent, Belgium) | Epoetin β (within 1 week post transplant). Starting dose was 150 U/kg 3X/week (sc), for a maximum of 12 weeks to maintain Hct between 25% and 35%. | No ESA | N = 29, ESA (14), control (15) | T1/2 sCr (the time for sCr to reach 50% of the pre-transplantation value for more than 2.5 days) | Increased Hb and reduced transfusions in ESA arm. No difference in sCr at any time point. |

Table 4.

Anemia correction studies

| Reference | Study Location | ESA | Duration of Therapy | Comparator Arm | Subjects (Total and # in groups) | Starting vs Achieved Hb High(H) or low(L) Hb Group (g/dL) | Other Renal Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham 1990 [38] | Hennepin County Medical Center Minneapolis Minn (USA) | Epoetin α (50–150 U/Kg 3X/w) to raise Hct to 37% vs 29%. | 8–12 weeks to raise Hct then patients received ESA | Placebo (unspecified) | N = 8: ESA(4), control(4) | L: 9.3 vs 9.7 H: 10.7 vs 12.3 |

After 18 weeks there was no difference in the 1/sCr curves and no difference in protein excretion |

| Clyne 1992 [39] | Karolinska Hospital, Danderyd Hospital Stockholm (Sweden) | Epoetin β (300 U/kg) 1X/week to raise Hb from 8.6 to 11.7 g/dL | 12 weeks | Placebo (unspecified) | N = 22: ESA(12), control(10) | L: 9.3 vs 9.4 H: 8.7 vs 11.3 |

No change in eGFR in either group. No significant difference in change in sCr |

| Kleinman 1989 [40] | Valley Presbyterian hospital, Van Nuys California (USA) | ESA (100 U/kg, 3x/week) to raise hct from 28 to 38–40% | 12 weeks | Placebo (unspecified) | N = 14: ESA(7), control(7) | L: 9.4 vs 9.4 H: 9.4 vs 11.9 |

No difference in sCr or change in sCr |

| Kuriyama 1997 [41] | Saiseikai Central hospital, Tokyo Japan | Epoetin β (6000 U/week) to raise hct from 25.5 to 35.5% | 36 weeks | No ESA | N = 108: ESA(42), control(66) | L: 9.3 vs 8.4 High Hb control 12.0 vs 10.7 H: 9.0 vs 11.8 |

Time to a doubling in sCr significantly slower in the ESA group. |

| Lim 1989 [42] | University of Iowa Hospitals’ Renal Clinic, Iowa (USA) | ESA (50, 100, or 150 U/kg 3X/week) | 8 weeks | Placebo (unspecified) | N = 13: ESA(11), control(2) | L: 9,0 vs 12.7 H: 9.0 vs 8.0 |

No change in renal function over 2 months in ESA group |

| Lim 1990 [43] | University of Iowa Hospitals’ Renal Clinic, Iowa (USA) | Epoetin α 3X/week, later switched to 1X/week to raise Hct from 28 to 36% | 11.8 ± 6.8 months (range 2.8-23.8) | No ESA | N = 20: ESA(10), control(10) | L: 11.0 vs 9.0 H: 9.3 vs 12.0 |

The rate of change in sCr was similar over 12 months |

| Revicki 1995 [18] | USA | Epoetin α (50 U/kg, 3X/week) then titrated to increase Hct from 27 to 35%. | 48 weeks | No ESA | N = 83: ESA(43), control(40) | L: 8.9 vs 8.6 H: 8.9 vs 10.5 |

No difference in change in eGFR after 48 weeks, no difference in time to dialysis |

| Akizawa 2011 [44] | Japan | Darbepoetin alfa (30 ug 1X/week) to target Hb 11–13 g/dL. | 48 weeks | rHuEpo (~4000 U/week) to maintain Hb at 9–11 g/dL. All received at least one dose of ESA | N = 321: High Hb (161), Low Hb (160) | L: 9.2 vs 10.1 H: 9.2 vs 11.9 |

No difference in 2 years decline in eGFR |

| Cianciaruso 2008 [45] | Italy | Epoetin α (2000 U 1x/week) to maintain Hb at 12–14 g/dL | 12 months | No ESA unless Hb dropped below 9 g/dL. 2/49 received ESA | N = 95: High Hb (46), Low Hb (49) | L: 11.7 vs 11.4 H: 11.6 vs 12.4 |

No significant difference in eGFR or sCr |

| Drueke 2006 [46] | 94 centers 22 countries | Epoetin β to raise Hb to a target of 13–15 g/dL. Median was 5000 U 1X/week | 48 months | Hb targeted to >10.5 g/dL. ESA only if Hb dropped below 10.5 g/dL. 67% received ESA during the study. Median 2000 U 1X/week | N = 603: High Hb (301), Low Hb (302) | L: 11.6 vs 11.4 H: 11.6 vs 13.5 |

No significant difference in the last eGFR value before initiation of dialysis. Time to initiation of dialysis was shorter in the high Hb group at 18 months (P = 0.03). |

| Gouva 2004 [47] | Greece | Epoetin α (50 U/kg 1x/week) to raise Hb from 9–11.6 g/dL to a Hb target of 13 g/dL | Treatment time was a median of 22.5 months (range 16–24) | No ESA for a median of 12 months (range 7–19), then no ESA unless Hb dropped below 9 g/dL. | N = 88: High Hb(45), Low Hb(43) | L: 10.1 vs 10.3 H: 10.1 vs 12.9 |

No difference in sCr |

| Levin 2005 [48] | Canada | Epoetin α (2000 U 1X/week) to raise and maintain Hb at 12.0–14.0 g/dL | 24 months | Low Hb (<11 g/dL), 16/74 received ESA | N = 172: High Hb(85) Low Hb(87) | L: 11.7 vs 11.4 H: 11.8 vs 12.8 |

No difference in creatinine clearance. Change in eGFR slower in the treatment group (not significant) |

| MacDougall 2007 [49] | United Kingdom | Epoetin α (1000 U 2X/week) to maintain Hb at 11.0 g/dl. Total was 190,000 U | 3 years | No ESA until Hb dropped below 9 g/dL (55/132 received ESA; total 152,000 U | N = 197: High Hb(65), Low Hb(132) | L: 10.9 vs 10.5 H: 10.8 vs 11.0 |

No difference in time to dialysis, creatinine clearance, change in creatinine clearance or death. |

| Pfeffer 2009 [50] | 623 sites in 24 countries | Darbepoetin alfa 0.75 mcg/kg (Q2W and switched to QM); to increase Hb from 10.4 to 12.5 g/dL. | 48 months; median duration of 29 months | No ESA until Hb dropped below 9 g/dL, 46% received 1 or more doses of ESA | N = 4038. High Hb(2012), low Hb(2026) | L:10.4 vs 10.6 H: 10.5 vs 12.5 |

No difference in the renal composite endpoint |

| Ritz 2007 [51] | 64 centers in 16 countries | Epoetin β (2000 U/week) to a target Hb of 13–15 g/dL. | 15 months | Hb target of 10.5–11.5 g/dL. 13/82 patients received ESA | N = 172: High Hb(89), Low Hb(83) | L: 11.7 vs 12.1 H: 11.9 vs 13.5 |

No effect on the rate of decrease in creatinine clearance, change in eGFR or urine protein |

| Roger 2004 [52] | Australia and New Zealand | Epoetin α 1X/week to increase Hb from 10 to 13 g/dL | 24 months | ESA if Hb below 9 g/dL, 8/78 received ESA | N = 155: High Hb(75), Low Hb(80) | L: 11.2 vs 11.0 H: 11.2 vs 12.2 |

No difference eGFR or creatinine clearance at 2 years |

| Rossert 2006 [53] | 93 centers in 22 countries | Epoetin α (25–100 U/kg 1X/week) to a Hb target of 13–15 g/dL. Median dose was 4,514 IU/week | 4 months Hb stabilization then 7.4 months maintenance (high Hb) or 8.3 months (low Hb) | Hb target of 11–12 g/day. 65/195 received at least 1 ESA dose. Ave dose 2,730 IU/week (333–7667) | N = 390: High Hb(195), Low Hb(195) | L: 11.5 vs 11.7 H: 11.6 vs 13.9 |

No significant differences in rates of decrease in eGFR |

| Singh 2006 [54] | 130 sites in USA | Epoetin α 1x/week to achieve Hb target of 13.5 g/dL. Ave 11,215 U/week | Median duration 16 months; 661 patients (46.2%) completed 36 months | Target Hb of 11 g/dL (709/717 received ESA) Ave dose 6276 U/week | N = 1432: High Hb (715), Low Hb (717) | L: 10.1 vs 11.3 H: 10.1 vs 12.6 |

No difference in hospitalization for RRT |

| Villar 2011 [55] | 15 centers in France | ESA to target a Hb of 13–14.9 g/dL. Mean weekly ESA dose 6028 ± 6729 IU | 24 months | Target Hb of 11–12.9 g/dL. Mean dose 1558 ± 1314 UI/week | N = 89: High Hb (46), Low Hb (43) | L: 11.5 vs 11.9 H: 11.4 vs 13.2 |

No difference in proteinuria or decline in eGFR (2 years) |

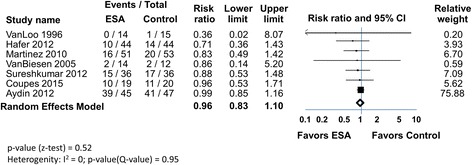

Fig. 3.

ESAs and incidence of AKI in patients at risk for AKI

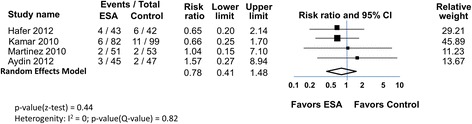

Fig. 4.

ESAs and DGF in patients undergoing kidney transplant

Fig. 5.

ESAs and graft loss in patients undergoing kidney transplant

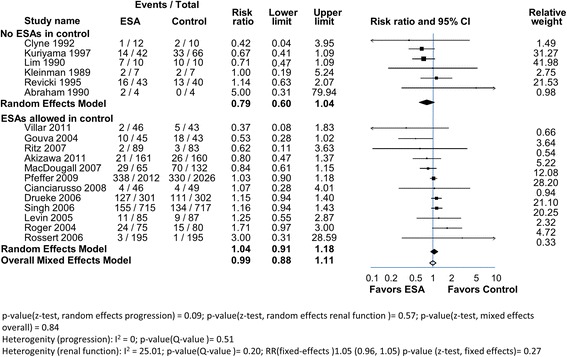

Fig. 6.

ESAs in anemic CKD patients. The 18 trials were divided into 2 groups. In 6 trials there was no ESAs administered in the control group. In 12 trials some patients in the control groups were given ESAs. The RR and range for each group (filled diamonds) and the overall RR (open diamond) are shown

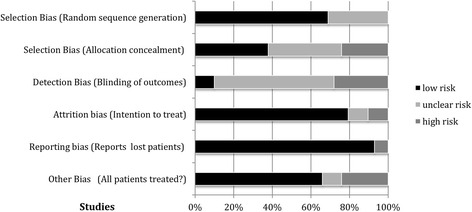

Data extracted to assess trial quality (bias) included randomization, concealment of allocation, masking of patients and clinicians, documentation of dropouts and withdrawals, and whether analysis was by intention-to-treat.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarized using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (V2) (Biostat, Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA). A random-effects model was used because it assumes treatment effects are not identical in all studies. However, results of analyses using a fixed-effects model, which assumes that the treatment effect is the same in each study and that differences in results are due only to chance, are also provided when the I2 statistic was not equal to zero. Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to compare results for patients treated with ESA with the control group. Heterogeneity or inconsistency across studies was assessed using Cochrane’s Q (p-value) and the I2 statistic. The p-value for the z-test comparing treatment groups was also determined.

Results

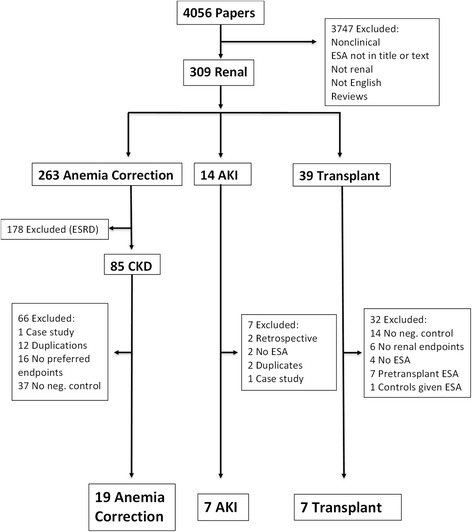

Description of searches and study selection criteria

The titles of papers from the searches were reviewed, and abstracts examined. Papers with potential relevance to ESAs, human clinical trials and tissue protection were recovered. This process resulted in 4056 papers. The selection and rejection process for these papers is shown in Fig. 1. Papers describing non-human studies, were reviews, were not clinical trials, lacked renal endpoints, were not in English, did not include a term for anemia, Hb or an ESA in the paper, or they did not otherwise fulfill the inclusion criteria were excluded. The resulting 309 papers described clinical trials with ESA-treated subjects that fell into 3 categories, at risk or presenting with AKI, ESA-treated kidney transplant patients and patients undergoing anemia correction with ESAs. Papers describing trials on dialysis patients, trials lacking a control group, trials that did not use ESAs, or were case studies, were omitted. Choukroun 2012 [11] was an anemia correction trial on renal transplant patients and not CKD patients so it was omitted. In 3 trials, ESAs were given prior to renal transplant [12–15] and omitted because there could be no direct effect of ESA on the ischemic transplanted kidney. Duplications were identified; Oh 2012 [16] was a reanalysis of Song 2009 [17] and Revicki 1995 [18] was a follow-up of Roth 1994 [19]. The Park (2005) [20] and Olweny (2012) [21] trials were excluded from meta-analysis because they were retrospective trials without AKI endpoints. 33 papers published between 1989 and 2015 remained, and their characteristics and extracted data are summarized in Tables 2, 3 and 4. Measures of renal function (sCr, eGFR, and enzymatic) varied, (methods and times), or were not reported in many papers. Therefore, we chose not to perform meta-analyses using those markers but instead summarize available data in the tables. Meta-analyses (Forrest plots) using the selected hard endpoints, are shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection

Risk of bias assessment

Trial quality (potential bias) was evaluated utilizing Jadad [22] and Cochrane recommendations. With the exception of Kamar 2010 [23] (which was a observational trial) all the trials used in meta-analysis were RCTs. Risk of bias assessment is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Most trials provided an ITT analysis with reporting of lost patients. The trials also had adequate methods to randomly distribute subjects into intervention vs control groups. Blinding of subject distribution and blinding of outcome to assessors was inadequate in most trials, particularly the anemia correction trials. However, the hard renal endpoints used in these meta-analyses are strengths. Most AKI and transplant trials were double-blinded with few dropouts, while the anemia correction trials were mostly open-label with variable numbers of dropouts. Overall, the trials had a risk of bias that was considered acceptable and thus results from meta-analysis would be informative.

Table 1.

Assessment of Risk of Bias of Randomized Controlled Trials

| Reference | Trial features | Randomized sequence | Allocation concealment | Blinding of outcome assessors | ITT analysis | Reports on Lost patients | All patients treated in assigned group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dardashti 2014 [24] | AKI: DB, SS | Low risk: patients were randomly allocated. | Low risk: sequentially numbered, sealed, & opaque envelopes. Independent nurses prepared the study drug & syringes were delivered blinded | High risk | High risk: 5 patients that received study drug were discontinued and excluded from analysis | Low risk: lost patients reported | Low risk: all patients treated |

| deSeigneux 2012 [76] | AKI: DB, SS | Low risk: a randomization code was generated by computer | Low risk: envelopes with allocation were prepared by the quality of care unit. A nurse opened the envelopes and prepared the syringes for injection. Investigators and patients were blinded to the treatment | High risk | Low risk: AKI data on all patients | Low risk: lost patients reported | Low risk: all patients treated |

| Endre 2010 [26] | AKI: DB, MS (2 centers) | Low risk: allocation by a predefined computer-generated randomization sequence | Low risk: concealment was by a pharmacist; pairs of identical syringes. Patients, all medical staff, & investigators were blinded to treatment | Low risk: Data Safety Monitoring Board with unmasking followed recording of the final AEs of the patient last enrolled | Low risk | Low risk: lost patients reported | Low risk: but 1 patient withdrew |

| Kim 2013 [27] | AKI: DB, SS | Low risk: computer-generated random code | Low risk: medications were prepared by a nurse who knew the patient’s group assignment but was not involved in the study | Unclear risk | Low risk: No dropouts | Low risk: lost patients reported | Low risk: all patients treated |

| Oh 2012 [16] | AKI: DB, SS | Low risk: A randomization code list with a block size of two was generated. Treatments were allocated to patients through the Internet in accordance with the predefined randomization list | Low risk: a research coordinator performed randomization and prepared the study drugs | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk: all patients completed the trial | Low risk: all patients completed the trial |

| Tasanarong 2013 [28] | AKI: DB, SS | Low risk: treatment assignment by blocked randomization. Sealed envelopes containing the allocation group were opened by nurses who did not participate in the study | Low risk: treatments were blindly given to the research coordinator. Patients and investigators were blinded to group assignment. Pairs of identical syringes containing either rHuEPO or saline were prepared | High risk | Low risk: No dropouts | Low risk: no dropouts | Low risk: no dropouts |

| Yoo 2011 [29] | AKI: OL(single blinded), SS | Low risk: patients were allocated by computer-generated random numbers | Unclear risk: medications were prepared and administered by a ward physician recognizing the patient’s group but not involved in the current study, the surgeon and anesthesiologist involved were blinded | Low risk: the surgeon and anesthesiologist involved in the study and patient management were blinded to the patients’ groups until the end of the study | Low risk: complete data sets from the 74 patients were analyzed without any missing data | Low risk: no dropouts | Low risk: complete data sets from the 74 patients were analyzed without any missing data |

| Aydin 2012 [31] | Transplant: DB, SS | Low risk: Patients were randomized by an independent hospital pharmacist. The randomization allocation sequence was generated by a random-number table | Low risk: patients, physicians, data managers and investigators were kept blinded throughout the study | Low risk: data managers and investigators were kept blinded throughout the study | Low risk: No dropouts | Low risk: No dropouts | Low risk: No dropouts |

| Coupes 2015 [30] | Transplant: DB, SS | Low risk: patients were randomly assigned by the trial pharmacy by computer | Low risk: all study participants and the study team were blinded to the trial drug | Unclear risk | Low risk: 1 patient withdrew but was included in the analysis | Low risk: lost patients reported | Low risk |

| Hafer 2012 [32] | Transplant: DB, SS | Unclear risk: randomization methodology not disclosed | Low risk: vials containing ESA and placebo had identical appearance | Unclear risk | Low risk for DGF. High risk for graft loss (3 patients died 1 in ESA group and 2 in placebo group) | Low risk: lost patients reported | High risk: 2 untreated patients (not included in analysis) and 3 patients died |

| Martinez 2010 [33] | Transplant: OL, MC | Unclear risk: randomization method not disclosed | High risk: comparator arm was untreated | Low risk: Blinded evaluation of end-points | Unclear risk: 1 died in ESA group | Low risk: lost patients reported | Low risk |

| Sureshkumar 2012 [34] | Transplant: DB, SS | Low risk: the hospital pharmacy created a schedule using random assignments to a series of patient study numbers | Low risk: ESA and placebo were both 1 ml syringes. The medications were administered in a double-blinded manner | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk: no dropouts | Low risk |

| Van Biesen 2005 [35] | Transplant: OL, SS | Unclear risk: randomization method not disclosed | High risk: open label | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk |

| Van Loo 1996 [36] | Transplant: OL, SS | Unclear risk: randomization method not disclosed | High risk: open label | High risk | Low risk: no deaths or withdrawals | Low risk: no deaths or withdrawal | Low risk: no deaths or withdrawals |

| Abraham 1990 [38] | Anemia correction: DB then OL, Anemia correction: SS | Unclear risk: randomization method not disclosed | Unclear risk: unspecified | High risk | Low risk: no dropouts | Low risk: no dropouts | Low risk |

| Clyne 1992 [39] | Anemia correction: OL, 2 center | Unclear risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk: for RRT | Low risk: lost patients reported | Low risk |

| Kleinman 1989 [40] | Anemia correction: DB, MC | Unclear risk: randomization method not specified | Unclear risk: unspecified | High risk | Unclear risk: no dropouts reported | Unclear risk: no dropouts reported | Low risk |

| Kuriyama 1997 [41] | Anemia correction: OL, SS | Unclear risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patients reported | Low risk |

| Lim 1989 [42] | Anemia correction: DB, SS | Low risk: randomization by third party | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk: lost patients reported | Low risk |

| Lim 1990 [43] | Anemia correction: OL, SS | Unclear risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk: no dropouts | Low risk: no dropouts | Low risk |

| Revicki 1995 [18] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk: for RRT endpoint | Low risk: lost patients reported | Unclear risk |

| Cianciaruso 2008 [45] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: randomization by computer at a separate site | Low risk: allocation was concealed from investigators, sequences were sequentially numbered in opaque envelopes opened in sequence | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patient reports | High risk: 1 patient in the treatment group did not receive ESA, study terminated early |

| Gouva 2004 [47] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: computer generated sequence | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patients reported | High risk: study prematurely terminated |

| Levin 2005 [48] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: computer generated sequence | Low risk: allocation was in sealed sequentially numbered opaque envelopes. Designated personnel opened the next number in sequence | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patient reports | High risk: only 77/85 in the high Hb group received ESA |

| MacDougall 2007 [49] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: randomized using central randomization procedures (ClinPhone) | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patients reported | High risk: patients in the high Hb group received ESA on day 1 but study was prematurely terminated |

| Pfeffer 2009 [50] | Anemia correction: DB, MC | Low risk: DB, and patients were randomly assigned with the use of a computer-generated, permuted-block design | Unclear risk | High risk | High risk: 9 patients were excluded prior to unblinding | Low risk: lost patient reports | High risk: 93.9% of the patients in the darbepoetin alfa group were receiving the assigned treatment at 6 months” |

| Ritz 2007 [51] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: randomization was performed centrally into treatment groups by using a block-size randomization procedure stratified by country | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patient reports | Unclear risk: patients in group 1 were started immediately ESA but 3 patients withdrew |

| Roger 2004 [52] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: patients were randomized according to computer-generated stratification tables | Low risk: order concealment was maintained until the intervention was assigned | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patient reports | Low risk |

| Rossert 2006 [53] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: patients were randomized according to computer-generated stratification schedule | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patient reports | High risk: study was terminated prematurely. Many subjects did not enter maintenance or withdrew |

| Villar 2011 [55] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: block-size randomization was used | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patients reported | Unclear risk: most patients likely received ESA but 6 patients died or withdrew |

| Akizawa 2011 [44] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: patients were assigned by a computer according to a minimization method | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patients reported | High risk: after 1 administration, 43 withdrew. |

| Drueke 2006 [46] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: randomization was performed centrally with the use of a dynamic randomization method | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patients reported | High risk: 75 in the high Hb group withdrew |

| Singh 2006 [54] | Anemia correction: OL, MC | Low risk: patients were assigned by computer-generated per-muted-block randomization | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk: lost patients reported | High risk: study was terminated early at the second interim analysis because power to demonstrate benefit was less than 5%, and there was a high withdrawal rate |

*RCT-randomized controlled trial, DB Double blind, OL Open label, MC Multicenter, SC Single center

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph

Outcomes and meta-analysis

AKI trials

Nine trials were identified [16, 20, 21, 24–29] that assessed whether ESAs might reduce the risk of AKI (Table 2). In 8 trials the subjects underwent cardiac surgery (coronary artery grafting, or valvular heart surgery involving cardiopulmonary bypass) and in 1 trial the subjects underwent partial nephrectomy. The combined number of subjects was 1020; 490 in the ESA groups and 530 in the control groups. The trial sizes ranged from 71 to 187 subjects. The number of ESA administrations were small (1 or 2) so there were little/no changes in Hb (Table 2).

The endpoint tested in the meta-analysis was the number of patients that developed AKI within 2–7 days (>50% increase serum creatinine, or >0.3 mg/dl increase, AKIN definition). Four of the trials were performed by overlapping members of the same study groups [16, 17, 27, 29]. Song (2009) and Oh (2012) analyzed the same 71 patients and patient data, but used different definitions of AKI. They increased the duration of observation to 72 instead of 48 h, and therefore had different numbers of patients that progressed to AKI. We used the determinations from Oh (2012) because it is more recent and the definition used is more complete (AKIN).

Overall 107 of 367 (29%) of the subjects developed AKI in the ESA groups, with 133 of 357 (37%) in the control groups (Fig. 3). The RR slightly favored the ESA arm, but it did not reach statistical significance using either the random effects (0.79 [0.55, 1.14]), or fixed effects models (0.85 [0.69, 1.05]). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 60%), 3 trials showed benefit in the ESA arm, while the other 4 were neutral, or favored the control arm. This heterogeneity is further apparent when other renal endpoints were examined (Table 2). In 1 trial [20] there was no difference in renal recovery, in 4 trials there was no difference in creatinine-based markers. However, in a 5th mixed results were reported. In a 6th creatinine markers favored slightly (p = 0.054) the ESA group and in the 7th, creatinine-based markers favored the ESA group. In 3 trials there was no difference in eGFR between groups, while in another trial, eGFR was improved in the ESA arm. Overall the secondary outcome analyses using non-creatinine-based renal biomarkers did not demonstrated significant reno-protection by ESAs. In 3 trials urine or plasma NGAL or serum cystatin C) were the same in both groups; in the 4th, urinary NGAL was lower in the ESA arm, although the significance of this difference is uncertain.

Renal transplant trials

Reinstitution of blood flow in cadaveric or live donor kidneys activates a sequence of events that results in renal injury, which may result in the development of DGF. DGF can translate into a decrease in long-term graft survival. In most ESA trials in transplant patients [14, 23, 30–36], DGF was defined as a requirement for dialysis within 7 days of the transplant [37]. In trials where multiple definitions were presented, data according to this definition was used. However, in some papers the definition of DGF was not disclosed, or an alternate measure was used (Table 3). The trial sizes were small to moderate in size (29–181 subjects). Like AKI trials, the number of ESA administrations were limited with little/no change in Hb.

A meta-analysis with 450 subjects utilizing the DGF endpoint (7 trials), is shown in Fig. 4. DGF developed in 92 of 223 (41%) in the ESA arms and 106 of 227 (47%) in the control arms. The RR was neutral using random or fixed effects models (0.96 [0.83, 1.10]. Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0%).

Meta-analysis of long term graft loss over 1 year in four trials showed similar outcomes (Fig. 5). Fifteen of 221 subjects (6.8%) had graft loss in the ESA arms and 21 of 241 (8.7%) in the control arms. The RR (0.78 [0.41, 1.48]) slightly favored the ESA arm but did not reach statistical significance. Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0%). Excluding the retrospective study [23] reduced the apparent benefit with 9/139 (6.5%) in the ESA arm and 10/142 (7.0%) having graft loss, and the RR was closer to neutral, but with a larger range (0.90 [0.37, 2.15]).

In the 7 trials, additional renal outcomes were reported that showed no differences between ESA and no-ESA groups (Table 3). These included creatinine-based endpoints (6 trials), eGFR (3 trials), proteinuria (1 trial), histological indices in graft biopsies at 6 weeks and 6 months post-transplant (1 trial), and low molecular weight urinary protein AKI biomarkers (NGAL and IL-18) (1 trial) [34].

Anemia correction trials

CKD patients are often anemic, and ESA treatment to increase and maintain Hb levels is long-term. Therefore, analysis of ESA anemia correction clinical trials is a potentially useful method to assess the effect of Hb increases, and oxygen delivery to renal tissues, on renal disease progression.

In the 19 anemia correction trials identified, CKD patients were typically divided into 2 groups; those remaining at their starting Hb (control) and those where ESAs were used to target a higher Hb. ESAs in the 19 trials [18, 38–55] were typically given 1-3 times per week to raise and maintain target Hb levels (Table 4). The achieved Hb levels in most trials were 11–13.5 g/dL, with increases of 1–2.5 g/dL above the starting level. Trial duration ranged from 2 to 48 months. Many subjects in the lower Hb groups received ESAs, but at lower doses. In some trials, there was no ESA treatment of patients in the control groups. We performed meta-analysis on all trials and a separate meta-analysis of trials where subjects in the control groups did not receive ESAs (Fig. 6).

Patients that progressed to RRT included those that began dialysis or received a transplant. In one trial a patient withdrew because of sepsis and AKI [48]. This event was included in the RRT endpoint of that study. No patients progressed to dialysis in either arm of the Lim 1989 [42] trial making it unsuitable for inclusion in a meta-analysis with a RRT endpoint.

The remaining 18 anemia correction trials had a combined total of 8020 subjects; 3964 in the treatment arm (higher Hb) and 4056 in the comparator (low Hb control) arm. Trials were of varying size; 3 had over 600 subjects. The initial and achieved Hbs in the 2 groups are shown in Table 4.

Overall, 768 (19.4%) of subjects in the treatment arm and 786 (19.3%) in the control arm, progressed to RRT (Fig. 6). With meta-analysis, the RR (random effects) of progression to RRT was 1.04 [0.91, 1.18] with low heterogeneity (I2 = 25.0%). This lack of effect on disease progression is supported in 18 trials by other assessments of change in renal function, including proteinuria, or creatinine based markers where there were no significant differences reported between groups (Table 4). However, in one trial time to a doubling in serum creatinine was significantly slower in the ESA group (Kuriyama 1997) [41]. This anemia correction meta-analysis does not assess direct ESA effects per se because subjects in both arms may have received ESAs. However, Hb levels increased in the ESA treatment/high Hb arms. Thus the absence of benefit argues that anemia correction per se is not reno-protective.

In 6 of the 18 anemia correction trials, subjects in the comparator arm did not receive ESAs [18, 19, 38–43]. These trials included a total of 268 subjects. 42 of 129 in the ESA group (33%) and 60 of 139 in the control group (43%) progressed to dialysis. Meta-analysis showed a trend towards improvement in the progression to RRT in the ESA treatment group but this did not reach statistical significance; the RR according to the random effects model was 0.79 [0.6, 1.04] (Fig. 6). The result was similar using the mixed effects model. Heterogeneity was low. Measures of serum creatinine over time showed no statistical difference in 6 of the 7 trials. Thus this select analysis also does not support either direct or indirect (anemia correction) beneficial effect on renal disease progression by ESAs.

Discussion

We assessed potential beneficial effects of ESA treatment on acute or chronic renal disease. One potential benefit is that ESAs might increase renal tissue survival and therefore renal function following ischemic events due to an interaction of ESAs with receptors resident on the surface of renal cells resulting in an anti-apoptotic effect. Alternatively, there may be mitigation of the negative effects of anemia, since anemia is associated with an increased risk of renal disease progression and allograft loss over the long term [56, 57]. However, these meta-analyses showed no clear benefit of short-term ESAs in AKI and transplant trials, where there was little change in Hb levels, arguing an absence of direct benefit. There was also no significant ESA benefit in longer-term anemia correction trials, regardless of whether the comparator group received or did not receive ESAs. Thus there appeared to be little short or long-term reno-protective benefit of ESAs, via direct (via activation of EPOR or via an interaction of ESA with an EPOR:CD131 hybrid receptor [9]) or indirect (increased Hb) mechanisms.

The lack of clear benefit of ESAs on renal disease is consistent with earlier meta-analyses. A meta-analysis with patients at risk for AKI showed no benefit of ESAs on incidence of AKI [58]. Another meta-analyses of effects of ESAs on CKD patients also showed no clear benefit on progression to RRT, comparing ESA treatment to no treatment [59] or comparing high vs low Hb targets [60, 61], nor was there was an association between ESA dose and annual GFR change or progression to ESRD [62].

Overall and to date, the potential cyto-protective effects of ESAs reported in animal models have generally not translated into benefit in humans, according to other studies examining benefit with other ischemic tissues [63]. There was no significant benefit of ESAs on infarct size in a meta-analyses of patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [64, 65], and no effect on nonfatal heart related events in a meta-analysis of ESA-treated patients with heart failure [66]. There was also no difference in a meta-analysis of retinopathy of prematurity in infants treated with ESAs [67]. There was no benefit of either ESA or increased Hb in an ESA trial on patients with traumatic brain injury [68, 69], and there was no benefit in a phase 3 trial with ESA treatment of stroke patients [70]. Taken together, these observations suggest that ESAs may not have the broad, robust, non-hematopoietic protective abilities described by some investigators, at least not in humans.

The gap between preclinical reports of benefit of ESAs in animals, and the absence of similar robust benefit in humans, has several explanations. Dose and dose regimens may be different, or the animal studies used homogeneous animal types under controlled conditions that cannot be mimicked in the clinic. Another possibility is that a benefit may have been unobservable because of the trial designs used. In this AKI meta-analysis the subjects were primarily cardiac patients and did not have only ischemia to the kidney as in animal studies and therefore may be immune to potential reno-protective ESA benefits.

There could also be other induced mechanisms that may confound the outcome data. For example, sepsis can affect outcomes and blood pressure can increase with ESA treatment and can negatively correlate with renal outcomes [71, 72]. However, control of blood pressure did not affect progression to ESRD in a clinical trial [73].

Alternatively, the beneficial conclusions of preclinical animal studies need to be reconsidered. There are many reports in animals showing a lack of effect of ESAs [1, 74]. The reno-protective hypothesis assumes that EPOR is present, and functional, at significant level on the surface of renal cells. However reports of EPOR presence are either assumed according to responses in tissue culture and in animals, or based on western or immunohistochemistry studies with anti-EPOR antibodies now shown to be nonspecific [75]. Recently a specific antibody to EPOR was discovered and western blots on renal tissue showed few, if any, detectable EPOR raising further questions about the validity of the hypothesis [10].

These meta-analyses have limitations. Majorities of included trials were small, single center, and had modest event rates. The anemia correction trials were larger, but conclusions around direct effects were confounded by the frequent use of ESAs in the comparator arm, though trials where the comparator arm did not receive ESAs similarly showed no benefit. Within each grouping (CKD progression, AKI, transplantation) there were differences in patient selection, treatment regimen and outcome definition. Finally, the meta-analyses were based on aggregated, not individual patient level data, which precluded adjustments for confounding factors such as age and comorbidities.

Conclusions

In contrast to some preclinical studies demonstrating reno-protection by ESAs in animals, anemia correction, prophylaxis or post-injury intervention with ESAs provided no significant clinical reno-protection in humans. This suggests that ESAs may not have robust, nor reproducible direct, or indirect, benefits on renal function.

Acknowledgements

We thank Allan Pollock for critically reviewing and providing comments of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors’ contributions

SE conceived of the study, participated in the design, performed literature searches, data extraction, quality assessment, and drafting and revising the manuscript. DT participated in the design, performed statistical analysis, contributed to the interpretation of data and revision of the manuscript. ZE participated in the design, evaluation of the data, quality assessments, contributed to the interpretation of data and drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

SE and DT are stockholders in Amgen Inc, a manufacturer and distributer of ESAs. SE was an employee, but currently receives no financial compensation from Amgen. Dianne Tomita is an employee of Amgen. None of the authors were directly compensated, had external funding sources or were provided administrative support for writing this paper. ZE has no financial conflicts to declare.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- AKIN

Acute kidney injury network

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- DGF

Delayed graft function

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- EPO

Erythropoietin

- EPOR

EPO receptor

- ESA

Erythropoiesis stimulating agent

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- ITT

Intention to treat

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RR

Risk ratios

- RRT

Renal replacement therapy

- SCr

Serum creatinine

Contributor Information

Steve Elliott, Phone: (805) 807-8009, Email: elliottsge@gmail.com.

Dianne Tomita, Email: diannet@amgen.com.

Zoltan Endre, Email: zoltan.endre@unsw.edu.au.

References

- 1.Elliott S, Sinclair AM. The effect of erythropoietin on normal and neoplastic cells. Biologics: Targets Therapy. 2012;6:163–89. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S32281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin FK, Suggs S, Lin CH, Browne JK, Smalling R, Egrie JC, et al. Cloning and expression of the human erythropoietin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:7580–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sico JJ, Concato J, Wells CK, Lo AC, Nadeau SE, Williams LS, et al. Anemia is associated with poor outcomes in patients with less severe ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:271–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosiborod M, Smith GL, Radford MJ, Foody JM, Krumholz HM. The prognostic importance of anemia in patients with heart failure. Am J Med. 2003;114:112–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramson JL, Jurkovitz CT, Vaccarino V, Weintraub WS, McClellan W. Chronic kidney disease, anemia, and incident stroke in a middle-aged, community-based population: the ARIC Study. Kidney Int. 2003;64:610–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki M, Hada Y, Akaishi M, Hiroe M, Aonuma K, Tsubakihara Y, et al. Effects of anemia correction by erythropoiesis-stimulating agents on cardiovascular function in non-dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease. Int Heart J. 2012;53:2012. doi: 10.1536/ihj.53.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahlmann FH, Fliser D. Erythropoietin and renoprotection. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18:15–20. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32831a9dde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore E, Bellomo R. Erythropoietin (EPO) in acute kidney injury. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:3. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Togel FE, Ahlstrom JD, Yang Y, Hu Z, Zhang P, Westenfelder C. Carbamylated Erythropoietin Outperforms Erythropoietin in the Treatment of AKI-on-CKD and Other AKI Models. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(11):3394–404. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015091059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott S, Busse L, Swift S, McCaffery I, Rossi J, Kassner P, et al. Lack of expression and function of erythropoietin receptors in the kidney. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2733–45. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choukroun G, Kamar N, Dussol B, Etienne I, Cassuto-Viguier E, Toupance O, et al. Correction of postkidney transplant anemia reduces progression of allograft nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:360–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasquez EM, Pollak R. Effect of pretransplant erythropoietin therapy on renal allograft outcome. Transplantation. 1996;62:1026–8. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199610150-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linde T, Ekberg H, Forslund T, Furuland H, Holdaas H, Nyberg G, et al. The use of pretransplant erythropoietin to normalize hemoglobin levels has no deleterious effects on renal transplantation outcome. Transplantation. 2001;71:79–82. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200101150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lietz K, Lao M, Paczek L, Gorski A, Gaciong Z. The impact of pretransplant erythropoietin therapy on late outcomes of renal transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2003;8:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Lucas M, Marcen R, Villafruela J, Teruel JL, Tato A, Rivera M, et al. Effect of rHuEpo therapy in dialysis patients on endogenous erythropoietin synthesis after renal transplantation. Nephron. 1996;73:54–7. doi: 10.1159/000188998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh SW, Chin HJ, Chae DW, Na KY. Erythropoietin improves long-term outcomes in patients with acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:506–11. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.5.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song YR, Lee T, You SJ, Chin HJ, Chae DW, Lim C, et al. Prevention of acute kidney injury by erythropoietin in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: a pilot study. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:253–60. doi: 10.1159/000223229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Revicki DA, Brown RE, Feeny DH, Henry D, Teehan BP, Rudnick MR, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with recombinant human erythropoietin therapy for predialysis chronic renal disease patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:548–54. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth D, Smith RD, Schulman G, Steinman TI, Hatch FE, Rudnick MR, et al. Effects of recombinant human erythropoietin on renal function in chronic renal failure predialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;24:777–84. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(12)80671-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park J, Gage BF, Vijayan A. Use of EPO in critically ill patients with acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:791–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olweny EO, Mir SA, Park SK, Tan YK, Faddegon S, Best SL, et al. Intra-operative erythropoietin during laparoscopic partial nephrectomy is not renoprotective. World J Urol. 2012;30:519–24. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamar N, Reboux A-H, Cointault O, Esposito L, Cardeau-Desangles I, Lavayssiere L, et al. Impact of very early high doses of recombinant erythropoietin on anemia and allograft function in de novo kidney-transplant patients. Transpl Int. 2010;23:277–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dardashti A, Ederoth P, Algotsson L, Bronden B, Grins E, Larsson M, et al. Erythropoietin and protection of renal function in cardiac surgery (the EPRICS Trial) Anesthesiology. 2014;121:582–90. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De SS, Ponte B, Weiss L, Pugin J, Romand JA, Martin P-Y, et al. Epoetin administrated after cardiac surgery: Effects on renal function and inflammation in a randomized controlled study. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Endre ZH, Walker RJ, Pickering JW, Shaw GM, Frampton CM, Henderson SJ, et al. Early intervention with erythropoietin does not affect the outcome of acute kidney injury (the EARLYARF trial) Kidney Int. 2010;77:1020–30. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J-H, Shim J-K, Song J-W, Song Y, Kim H-B, Kwak Y-L. Effect of erythropoietin on the incidence of acute kidney injury following complex valvular heart surgery: A double blind, randomized clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Crit Care. 2013;17:R254. doi: 10.1186/cc13081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tasanarong A, Duangchana S, Sumransurp S, Homvises B, Satdhabudha O. Prophylaxis with erythropoietin versus placebo reduces acute kidney injury and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: A randomized, double-blind controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoo Y-C, Shim J-K, Kim J-C, Jo Y-Y, Lee J-H, Kwak Y-L. Effect of single recombinant human erythropoietin injection on transfusion requirements in preoperatively anemic patients undergoing valvular heart surgery. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:929–37. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318232004b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coupes B, de Freitas DG, Roberts S, Read I, Riad H, Brenchley PE, et al. rhErythropoietin-b as a tissue protective agent in kidney transplantation: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:1. doi: 10.1186/s13104-014-0964-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aydin Z, Mallat MJK, Schaapherder AFM, van Zonneveld AJ, Van KC, Rabelink TJ, et al. Randomized trial of short-course high-dose erythropoietin in donation after cardiac death kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(7):1793–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hafer C, Becker T, Kielstein JT, Bahlmann E, Schwarz A, Grinzoff N, et al. High-dose erythropoietin has no effect on short-or long-term graft function following deceased donor kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2012;81:314–20. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez F, Kamar N, Pallet N, Lang P, Durrbach A, Lebranchu Y, et al. High dose epoetin beta in the first weeks following renal transplantation and delayed graft function: Results of the Neo-PDGF study: Brief communication. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1704–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sureshkumar KK, Hussain SM, Ko TY, Thai NL, Marcus RJ. Effect of high-dose erythropoietin on graft function after kidney transplantation: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1498–506. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01360212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Biesen W, Vanholder R, Veys N, Verbeke F, Lameire N. Efficacy of erythropoietin administration in the treatment of anemia immediately after renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;79:367–8. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000150370.51700.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Loo A, Vanholder R, Bernaert P, Deroose J, Lameire N. Recombinant human erythropoietin corrects anaemia during the first weeks after renal transplantation - a randomized prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:1815–21. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siedlecki A, Irish W, Brennan DC. Delayed graft function in the kidney transplant. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2279–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abraham PA, Opsahl JA, Rachael KM, Asinger R, Halstenson CE. Renal function during erythropoietin therapy for anemia in predialysis chronic renal failure patients. Am J Nephrol. 1990;10:128–36. doi: 10.1159/000168067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clyne N, Jogestrand T. Effect of erythropoietin treatment on physical exercise capacity and on renal function in predialytic uremic patients. Nephron. 1992;60:390–6. doi: 10.1159/000186797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleinman KS, Schweitzer SU, Perdue ST, Bleifer KH, Abels RI. The use of recombinant human erythropoietin in the correction of anemia in predialysis patients and its effect on renal function: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 1989;14:486–95. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(89)80149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuriyama S, Tomonari H, Yoshida H, Hashimoto T, Kawaguchi Y, Sakai O. Reversal of anemia by erythropoietin therapy retards the progression of chronic renal failure, especially in nondiabetic patients. Nephron. 1997;77:176–85. doi: 10.1159/000190270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim VS, DeGowin RL, Zavala D, Kirchner PT, Abels R, Perry P, et al. Recombinant human erythropoietin treatment in pre-dialysis patients. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:108–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-2-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lim VS, Fangman J, Flanigan MJ, DeGowin RL, Abels RT. Effect of recombinant human erythropoietin on renal function in humans. Kidney Int. 1990;37:131–6. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akizawa T, Gejyo F, Nishi S, Iino Y, Watanabe Y, Suzuki M, et al. Positive outcomes of high hemoglobin target in patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis: a randomized controlled study. Ther Apher Dial. 2011;15:431–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2011.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cianciaruso B, Ravani P, Barrett BJ, Levin A, ITA EPO. Italian randomized trial of hemoglobin maintenance to prevent or delay left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol. 2008;21:861–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drueke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, Eckardt KU, Macdougall IC, Tsakiris D, et al. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2071–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gouva C, Nikolopoulos P, Ioannidis JP, Siamopoulos KC. Treating anemia early in renal failure patients slows the decline of renal function: a randomized controlled trial. Kidney Int. 2004;66:753–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levin A, Djurdjev O, Thompson C, Barrett B, Ethier J, Carlisle E, et al. Canadian randomized trial of hemoglobin maintenance to prevent or delay left ventricular mass growth in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:799–811. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macdougall IC, Temple RM, Kwan JT. Is early treatment of anaemia with epoetin-alpha beneficial to pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients? Results of a multicentre, open-label, prospective, randomized, comparative group trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:784–93. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Eckardt KU, et al. A Trial of Darbepoetin Alfa in Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2019–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ritz E, Laville M, Bilous RW, O’Donoghue D, Scherhag A, Burger U, et al. Target level for hemoglobin correction in patients with diabetes and CKD: primary results of the Anemia Correction in Diabetes (ACORD) Study.[Erratum appears in Am J Kidney Dis. 2007 Apr;49(4):562] Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:194–207. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roger SD, McMahon LP, Clarkson A, Disney A, Harris D, Hawley C, et al. Effects of early and late intervention with epoetin alpha on left ventricular mass among patients with chronic kidney disease (stage 3 or 4): results of a randomized clinical trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:148–56. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000102471.89084.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rossert J, Levin A, Roger SD, Horl WH, Fouqueray B, Gassmann-Mayer C, et al. Effect of early correction of anemia on the progression of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:738–50. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.02.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, Barnhart H, Sapp S, Wolfson M, et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2085–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Villar E, Lievre M, Kessler M, Lemaitre V, Alamartine E, Rodier M, et al. Anemia normalization in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: results of the NEPHRODIAB2 randomized trial. J Diabetes Complications. 2011;25:237–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chhabra D, Grafals M, Skaro AI, Parker M, Gallon L. Impact of anemia after renal transplantation on patient and graft survival and on rate of acute rejection. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1168–74. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04641007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamar N, Rostaing L. Negative impact of one-year anemia on long-term patient and graft survival in kidney transplant patients receiving calcineurin inhibitors and mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 2008;85:1120–4. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816a8a1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tie HT, Luo MZ, Lin D, Zhang M, Wan JY, Wu QC. Erythropoietin administration for prevention of cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48:32–9. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cody J, Daly C, Campbell M, Donaldson C, Khan I, Rabindranath K, et al. Recombinant human erythropoietin for chronic renal failure anaemia in pre-dialysis patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;20(3):CD003266. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003266.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmer SC, Navaneethan SD, Craig JC, Johnson DW, Tonelli M, Garg AX, et al. Meta-analysis: erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:23–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-1-201007060-00252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Covic A, Nistor I, Donciu M-D, Dumea R, Bolignano D, Goldsmith D. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis of 19 studies. Am J Nephrol. 2014;40:13. doi: 10.1159/000366025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koulouridis I, Alfayez M, Trikalinos TA, Balk EM, Jaber BL. Dose of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents and Adverse Outcomes in CKD: A Metaregression Analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:44–56. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Solling C. Organ-protective and immunomodulatory effects of erythropoietin - an update on recent clinical trials. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;110:113–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li J, Xu H, Gao Q, Wen Y. Effect of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:469–77. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1160-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wen Y, Xu J, Ma X, Gao Q. High-dose erythropoietin in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2013;13:435–42. doi: 10.1007/s40256-013-0042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Desai A, Lewis E, Solomon S, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer M. Impact of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure: An updated, post-TREAT meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:936–42. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ohlsson A, Aher SM. Early erythropoietin for preventing red blood cell transfusion in preterm and/or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD004863. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004863.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robertson CS, Hannay HJ, Yamal JM, Gopinath S, Goodman JC, Tilley BC, et al. Effect of erythropoietin and transfusion threshold on neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:36–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nichol A, French C, Little L, Haddad S, Presneill J, Arabi Y, et al. Erythropoietin in traumatic brain injury (EPO-TBI): a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2499–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ehrenreich H, Weissenborn K, Prange H, Schneider D, Weimar C, Wartenberg K, et al. Recombinant human erythropoietin in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:e647–56. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.564872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Uzu T, Kida Y, Yamauchi A, Kume S, Isshiki K, Araki S, et al. The effects of blood pressure control levels on the renoprotection of type 2 diabetic patients without overt proteinuria. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Imai E, Ito S, Haneda M, Harada A, Kobayashi F, Yamasaki T, et al. Effects of blood pressure on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes and overt nephropathy: a post hoc analysis (ORIENT-blood pressure) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:447–54. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Loriga G, Ganeva M, Ene-Iordache B, Turturro M, et al. Blood-pressure control for renoprotection in patients with non-diabetic chronic renal disease (REIN-2): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:939–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sinclair AM, Coxon A, McCaffery I, Kaufman S, Paweletz K, Liu L, et al. Functional erythropoietin receptor is undetectable in endothelial, cardiac, neuronal, and renal cells. Blood. 2010;115:4264–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Elliott S, Busse L, Bass MB, Lu H, Sarosi I, Sinclair AM, et al. Anti-Epo receptor antibodies do not predict Epo receptor expression. Blood. 2006;107:1892–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DeSeigneux S, Ponte B, Weiss L, Pugin J, Romand JA, Martin P-Y, et al. Epoetin administrated after cardiac surgery: Effects on renal function and inflammation in a randomized controlled study. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.