Abstract

Background:

Coercion is not uncommon phenomenon among mental health service users during their admission into psychiatric hospital. Research on perceived coercion of psychiatric patients is limited from India.

Aim:

To investigate perceived coercion of psychiatric patients during admission into a tertiary care psychiatric hospital.

Materials and Methods:

This was a cross-sectional descriptive survey carried out among randomly selected psychiatric patients (n = 205) at a tertiary care center. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews using structured questionnaire.

Results:

Our findings revealed that participants experienced low levels of coercion during their admission process. However, a majority of the participants were threatened with commitment (71.7%) as well as they were sad (67.8%), unpleased (69.7%), confused (73.2%), and frightened (71.2%) with regard to hospitalization into a psychiatric hospital. In addition, the participants expressed higher levels of negative pressures (mean ± standard deviation, 3.76 ± 2.12). Participants those were admitted involuntarily (P > 0.001), diagnosed to be having psychotic disorders (P > 0.003), and unmarried (P > 0.04) perceived higher levels of coercion.

Conclusion:

The present study showed that more formal coercion was experienced by the patients those got admitted involuntarily. On the contrary, participants with voluntary admission encountered informal coercion (negative pressures). There is an urgent need to modify the Mental Health Care (MHC) Bill so that treatment of persons with mental illness is facilitated. Family member plays an important role in providing MHC; hence, they need to be empowered.

KEYWORDS: Admission experiences, coercion, mental health users, psychiatry

Introduction

Coercion is one of the most controversial aspects in the treatment and management of psychiatric disorders.[1] Coercion is the negative subjective experience of loss of autonomy caused by an involuntary action, in this case from the mental health services toward a patient.[2] Further perceived coercion of psychiatric patients would have a strong negative impact on treatment adherence.[3]

In India, like in any other developing countries coerced hospital admissions are acceptable for any person who suffers from a psychiatric disorder and poses danger to oneself or others.[4] However, coercive measures are widely regarded as an important human rights issue according to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities[5] and mental health users.[6] A recent literature review on the prevalence of perceived coercion of psychiatric patients revealed that the prevalence of perceived coercion ranged from 16% to 90%.[7] Coercion becomes inevitable in psychiatry, considering the nature of illness (psychotic) and when they become dangerous to self and/or others. In addition, studies on coercion in psychiatric admission have reported that involuntary admission presented more coercive feelings.[8] Nonetheless, coerced hospital admissions are influenced by various factors such as economical, cultural and religious beliefs, diagnosis, knowledge about illness, insight, available resources, and social and family support. The research that examined perceived coercion of psychiatric patients is limited in India. Furthermore, research on the issue of coercion in psychiatry is an urgent concern as it has greater impact on treatment adherence and it is important to gain more insight into the perceptions of patients regarding the experience of the admission process, which is crucial in reviewing and implementing Mental Health Care Bill, 2013 (MHC Bill, 2013).[4] For these reasons, the present study was aimed to investigate the perceived coercion of psychiatric patients during admission into a psychiatric hospital keeping the current Mental Health Act 1987 and MHC Bill, 2013, in perspective.

Materials and Methods

Sample

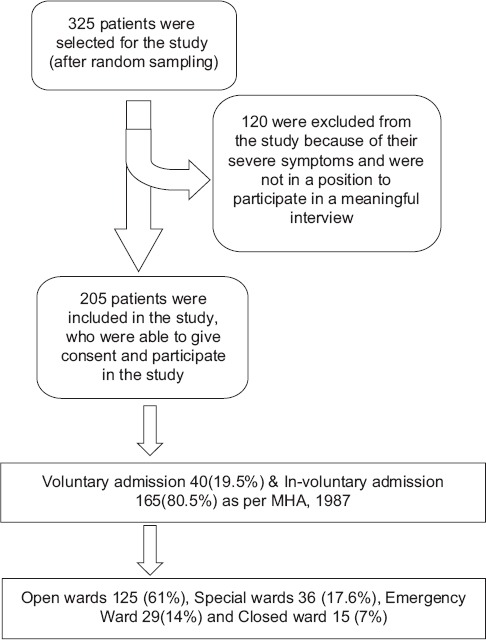

All the patients those were admitted in a tertiary hospital during the year 2015 were included in the present study. The study population was selected randomly from admission register. Among them, those who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. The inclusion criterion includes: (a) Patients admitted with psychiatric illnesses as International Classification of Diseases-10 criteria, (b) all individuals 18 years and above, and (c) willing to participate and were able to give the informed consent. Patients with acutely symptomatic (dangerous to self and/or others), organic diagnoses including mental retardation, substance abuse dementia, delirium, or organic brain diseases were excluded from the study. In total, 325 patients were approached [Flow Chart 1]. Among them, 120 (36.9%) could not to participate due to severe symptoms and could not be enrolled in the study. Hence, the final sample for the study comprised 205 patients with 63% response rate.[INLINE:1]

Measures

The instrument has two sections

Sociodemographic data sheet

Sociodemographic details include age, gender, educational status, marital status, employment, residence, religion, monthly income, diagnosis, types of admission, reasons for admission according to patient and family, history of past hospitalization, living situation, history of substance abuse, insight into mental illness, need for hospitalization, and whether first consultation was with psychiatrist or others.

MacArthur admission experience survey

This scale was developed by MacArthur Research Network on Mental Health and the Law to assess patients’ perceptions of coercion during their admission to psychiatric hospital.[9] This was a 20-point self-rating scale with four subscales to capture specific dimensions of perceived coercion as follows: Perceived coercion subscale (items 1, 4, 7, 14, and 15) - the influence, control, choice, and freedom that patients had in their admission (e.g. I chose to come into the hospital), negative pressure subscale (items 2, 6, 8, 10, 11, and 12) - the amount of persuasion, threat, inducements, and force used on patients to get them into the hospital (e.g. people tried to force me to come into the hospital), voice subscale (items 3, 5 and 13), and affective reaction subscale (item 16 with its 6 affective components such as angry, sad, pleased, relieved, confused, and frightened).[10] This questionnaire was used because the items were simple and easy to understand and answer. Further studies indicate high level of consistency between the subscales and the total score of the MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (MAES).[1]

Data collection procedure

A pilot study was conducted among a small group of participants, and it was that the tool was feasible to conduct the study. Before data collection, all the researchers discussed the items in the questionnaire. The participants were approached within 48 h of admission into psychiatric hospital. The participants those who met the inclusion criteria were explained by the researchers about the aims and objectives of the study. After obtaining the written informed consent from the participants, the data were collected using face-to-face interview using the structured questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institute Ethics Committee. Participation in this study was voluntary, and each participant was informed that their decision to participate or not, would in no way not affect his or her treatment. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants, and they were given freedom to withdraw from the study at any time. Further, we did not offer any compensation for participating in this study. All responses to the questionnaire remained confidential, and a code was used so participants could not be identified from their responses.

Statistical analysis

Negative items (12 and 13) were reverse coded before the analysis. Data were analyzed using appropriate statistical software. Descriptive (frequency and percentage) and inferential statistics (t-test) were used to interpret the data. Statistical significance was assumed at P > 0.05.

Results

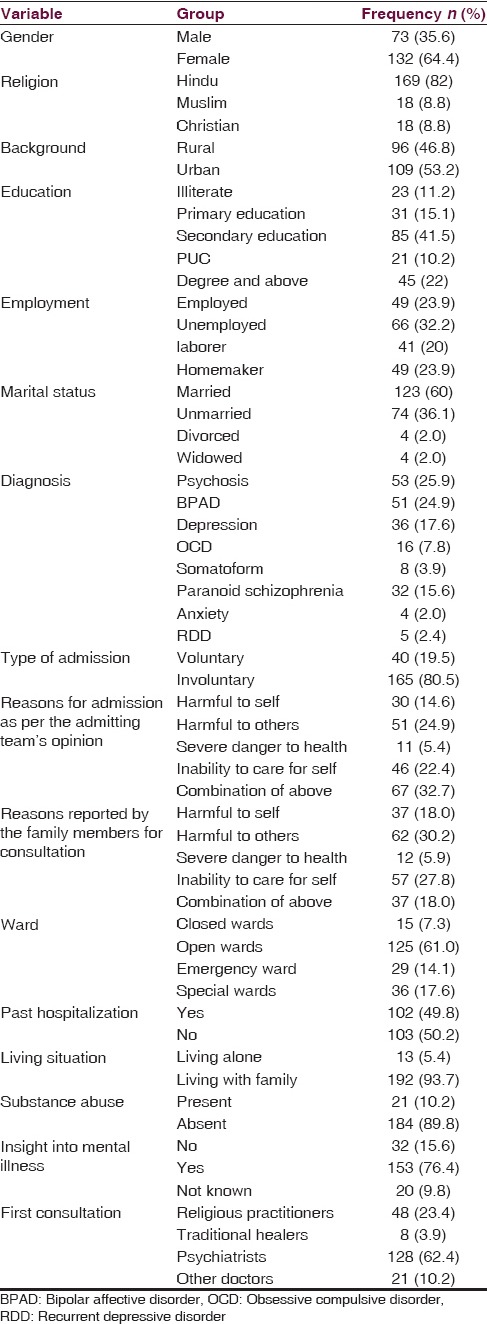

A total of 205 mental health consumers participated in the present study of whom, a majority was women (64.4%). Participants were predominantly young to middle-aged adults (mean age, 35 years), A majority of them were Hindus (82%), married (60%), and were from urban background (53.2%). More number of (86.3%) participants’ was diagnosed as psychotic disorders such as psychosis, bipolar affective disorders, and paranoid schizophrenia and admitted to the psychiatric hospital involuntarily. Half of the participants were first time admitted into the psychiatric hospital. Interestingly, more than three-fourth of the participants had insight about their illness and agreed that they were in need of hospitalization. Although majority of the participants first consulted psychiatrists (62.4%), 27.3% met the religious practitioners and traditional healers [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample

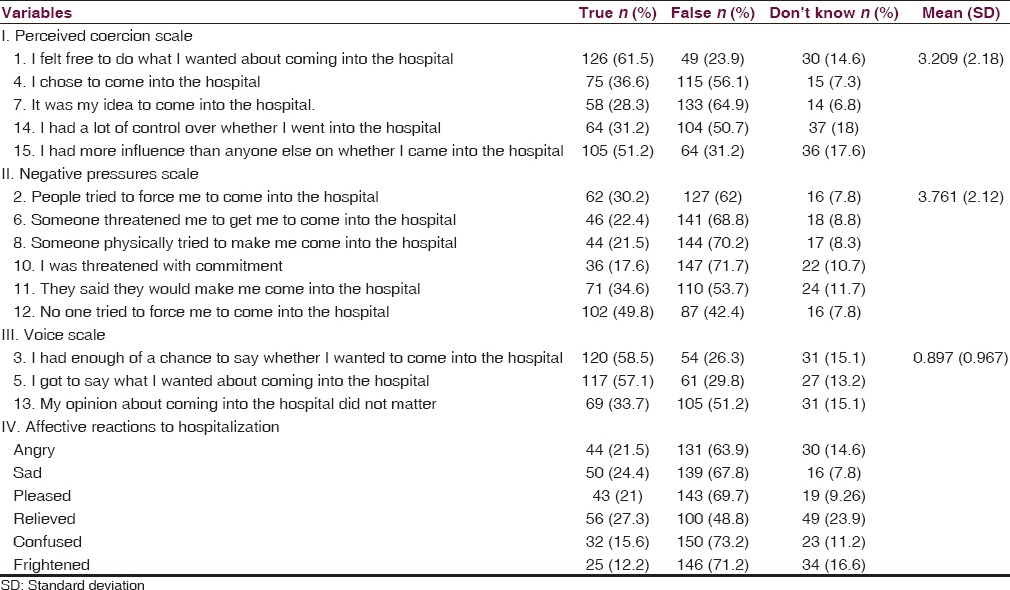

Table 2 summarizes the mental health consumers’ admission experiences into the psychiatric hospital. With regard to “Perceived Coercion” domain, majority of the participants “felt free to do what they wanted about coming into the hospital” (61.5%) and they had “more influence than anyone else on whether they came into the hospital” (51.2%). However, majority of them were contradicted with the items such as “I chose to come into the hospital” (56.1%), “It was my idea to come into the hospital” (64.9%) and “I had a lot of control over whether I went into the hospital” (50.7%). Although most of the sample agreed that people did not force (62%), threatened (68.8%), and physically tried (70.2%) them to come to the hospital, a majority of them were threatened with commitment (71.7%). The mean score for negative pressure subscale was mean ± standard deviation, 3.76 ± 2.12, which indicates a higher level of coercion in this domain. Participants responded positively to the items in “voice scale” domain as they had enough of a chance (58.5%) and got to say whether they wanted to come to the hospital (57.1%). However, more than half of them accorded that their opinion about coming into the hospital did not matter. With regard to the participants’ affective reactions to hospitalization, majority of them were sad (67.8%), unpleased (69.7%), unrelieved (48.8%), confused (73.2%), and frightened (71.2%).

Table 2.

Participants’ responses to MacArthur's Admission Experience Survey scale

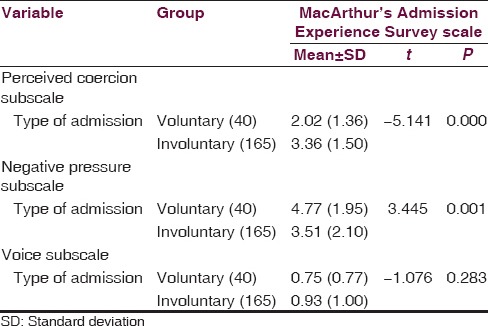

Table 3 depicts comparative responses on MAES of the participants from the type of admission (voluntary vs. involuntary admission). Participants those were admitted involuntarily reported to have significantly more on perceived coercion subscale (t = −5.141, P > 0.0001) and voluntarily admitted participants reported significantly more on negative pressure subscale (t = 3.445, P > 0.001); however, there was no significant difference between the group with regard to voice subscale.

Table 3.

Comparison between voluntary and involuntarily admitted patients on AES subscales

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that investigated admission experiences of psychiatric patients from India using internationally standardized questionnaire with random sampling. However, the present study has certain limitations such as cross-sectional survey and sample was limited to a single setting. Persons with acutely symptomatic were excluded from the study; hence, this limits the generalization of findings. Excluding extremely symptomatic (dangerous to self and/or others) patient plays important bias as these patients would likely to experience high levels of coercion on one hand, but at the same time, capturing the qualitative information during the interview is nearly impossible and validity of such information from such patients are questionable because of loss of reasoning power. However, the present study was carried out at a tertiary care center among randomly selected sample and who were in a position to give consent. Hence, our sample is likely to be representative of the study site population who were willing to participate and cooperative. This study is not applicable to those patients who are acutely symptomatic and/or difficult to interview. In India, the majority of the family members provide care to these acutely symptomatic patients, and they use all possible measures so that their family member is treated and becomes normal, which in turns he/she regains liberty.

In the present study, participants perceived lower levels of coercion. However, most of the sample expressed informal coercion that included negative pressures such as persuasion, threat, and force to come into the hospital. In the current study, most of the sample was women and married. While these findings were dissimilar to other studies on coerced admission into psychiatric hospital, similar in terms of unemployment as more number of the participants were unemployed.[11,12,13]

In line with previous research,[14,15,16] most of the sample in the present study was admitted involuntarily. These findings could be due to more number of the patients were diagnosed with psychotic disorders. However, studies indicate that mental health service users’ views about their involuntary admission have been shown to change over time.[16,17] In support of published research,[16,17] 82.4% of the participants agreed that they were in need of hospitalization.

Earlier research indicates that seeking religious help for mental disorders is often a first step in the management of mental disorders as a result of cultural explanations for the illness.[18] Similar to these findings, nearly one-fourth of the participants in this study visited religious practitioners for the treatment of mental illness. These findings could be due to widely prevalent magic-religious beliefs that were related with mental illness and also were culturally and socially accepted in India. Further, low literacy, low economic status, and stigma associated with mental illness were the obstacles in seeking help from mental health services.[19,20]

Several studies showed that mental health service users report high levels of perceived coercion during the admission process and over the course of their admission.[13,21] Dissimilar to these findings, most of the sample expressed low levels of coercion during their admission into psychiatric hospital. However, our findings were consistent with studies that indicate significant relation between MAES and legal status of admission. The involuntarily admitted patients perceived significantly higher levels of formal coercion than the participants with volunteer admission.[4,22,23,24] Similarly, participants with psychotic disorders such as psychosis, schizophrenia, and unmarried patients experienced higher levels of coercion. These findings were consistent with previous research.[25,26] The possible explanation for these findings could be due to the presence of psychotic symptoms among the participants. Earlier published research indicates that perceived coercion could be a barrier to mental health service use and a more sensitive approach to informal coercion might be beneficial for long-time adherence.[27] The present study also observed informal coercion of the voluntarily admitted patients (P = 0.001). Family members and the general public are willing to accept the coerciveness of people with mental illness to improve treatment adherence. Hence, they influence the people with mental illness with negative pressures such as threat or physical force to admit them into the psychiatric hospital. Further, in support of previous research,[3,28] participants with the presence of insight into illness encountered informal coercion during their admission process. On the other hand, psychiatric patients with lack of insight into mental illness perceived high levels of coercion.[8] Similarly, participants those diagnosed with neurotic disorders and married felt high levels informal coercion to admit into the psychiatric hospitals. However, gender, background, and experience of past hospitalization did not found any statistically significant difference with MAES scale.

Study findings implications on the Mental Health Care Bill, 2013

This study was done in a tertiary care center and had 80% involuntary admission under Mental Health Act, 1987. The main reasons quoted by the admitting physician for involuntary admissions were as follows 25% harm to others, 22% unable to care for themselves, 14% harm to self, and 32% combination of the above factors.

Although 325 patients were approached for the study, only 205 were able to be enrolled. Among them, 120 of them could not to participate due to severe symptoms and could not be enrolled in the study. Almost more than 50% of the study population were excluded because of their severe symptoms and could not be included in the study [Flow Chart 1]. An important significant finding was that 192 (93.7%) patients were living with family members and they were the primary caregivers. As per the family members, 30% harm to others, 28% unable to care for themselves, 18% harm to self, and 18% combination of the above factors. Role of family members in providing mental health care is an important asset in our society and needs to be fostered. If family members are not empowered and supported, in no time, these patients will be disowned and subsequently, a large number of patients will be wandering mentally ill at large.

Flow Chart 1.

Recruitment of the participants

The draft MHC Bill, 2013, is rights-based and gives enormous amount of power to the patient but disengages family members. The best example is Clause 4 of the Bill (Capacity to consent for treatment) discusses the patient's capacity - every person shall be deemed to have capacity to make decisions regarding his mental health care or treatment, if such person has ability to (a) understand information, (b) retain information, (c) use or weigh information, and (d) communicate his decision. The limitations of the above criteria are not been taken into consideration. For example, a person with mental illness symptoms may fulfill all the above four criteria, yet he may refuse to acknowledge that he/she is suffering from illness and may refuse treatment (absent insight patient). Similarly, patient's paranoid symptoms may also come in his way of decision-making process. Depressed patient may answer all necessary questions but may refuse treatment. Hence, there is a need to add one more criteria stating that if a person is suffering from such a mental disorder in which his/her symptoms interfere his/her decision-making process, and then his/her decisions need to be considered incompetent. Otherwise, family members providing care will face the consequences of the patient's illness if he refuses to take treatment.

MHC Bill, 2013, gives clear dictates about the procedure for involuntary admission procedure but does not discusse the involuntary or compulsory treatment for involuntary admission patients or treatment in community. To treat a patient against his will, one has to approach the mental health commission to get the approval. However, this process of mental health treatment, is a litigation based and cost the family members a enormously as well delays in initiating the treatment. There is no mention about the huge resource-mobilization that is required to realize various promises that the Bill is holding out. Hence, the MHC Bill needs to facilitate in providing adequate resources before implementing the planned Bill. Adequate resources in terms of a number of mental hospitals beds, general hospitals beds for persons with mental illness, psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, psychiatric social worker, psychiatric nursing, and adequate budget for providing mental health care. There is an urgent need to modify the Bill to empower family members.

The present study clearly establishes that coercion is present, and it is part of providing psychiatric services. There is an urgent need to increase the workforce phenomenally so that counseling and treatment can be given at doorsteps and coercion can be decreased. If not the Bill will be disaster for both family members and persons with mental illness with regard to providing care.

Conclusion

The present study showed that more formal coercion was experienced by the patients those got admitted involuntarily. On the contrary, participants with voluntary admission encountered informal coercion (negative pressures). However, there is an urgent need to educate the caregivers of persons with mental illness to respect the rights of psychiatric patients. There is an urgent need to modify the MHC Bill so that treatment of persons with mental illness is facilitated. Family member plays an important role in providing mental health care; hence, they need to be empowered. Future research should focus on interventional studies that reduce the perception of coercion including involvement of psychiatric patients in the treatment and management of illness.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are gratefully thankful to all the participants for their valuable contribution.

References

- 1.Morcos M. Perceived Coercion, Adherence To Treatment And Personality Traits; An Observational Cross Sectional Study. University of Manchester. 2012. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar]. Available at https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/api/datastream?publicationPid=uk-ac-man-scw:156819&datastreamId=FULL-TEXT.PDF .

- 2.Rhodes M. The nature of coercion. J Value Inq. 2000;34:369–81. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaeger M, Rossler W. Enhancement of outpatient treatment adherence: Patients’ perceptions of coercion, fairness and effectiveness. Psychiatry Res. 2010;180:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu JC, Chow PP, Lam LC. The experience of admission to psychiatric hospital among Chinese adult patients in Hong Kong. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UN. Human Rights – Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Ch. IV. New York: 2006. Dec 13, [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY and mtdsg_no=IV-15 and chapter=4 and lang=en . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlin J, Lehmann P. Declaration of Dresden Against Coerced Psychiatric Treatment. Dresden: 2007. Jun 7, [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.mindfreedom.org/kb/mental-health-global/wpa-dresden/dresden-declaration-wpa.pdf/view . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newton-Howes G, Stanley J. Prevalence of perceived coercion among psychiatric patients: Literature review and meta-regression modelling. Psychiatrist. 2012;36:335–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bindman J, Reid Y, Szmukler G, Tiller J, Thornicroft G, Leese M. Perceived coercion at admission to psychiatric hospital and engagement with follow-up – A cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:160–6. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0861-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner W, Hoge SK, Bennett N, Roth LH, Lidz CW, Monahan J, et al. Two scales for measuring patients’ perceptions for coercion during mental hospital admission. Behav Sci Law. 1993;11:307–21. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2370110308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daffern M, Thomas S, Ferguson M, Podubinski T, Hollander Y, Kulkhani J, et al. The impact of psychiatric symptoms, interpersonal style, and coercion on aggression and self-harm during psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatry. 2010;73:365–81. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2010.73.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kallert TW, Glöckner M, Schützwohl M. Involuntary vs. voluntary hospital admission. A systematic literature review on outcome diversity. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258:195–209. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsakou C, Priebe S. Outcomes of involuntary hospital admission – A review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:232–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Priebe S, Katsakou C, Amos T, Leese M, Morriss R, Rose D, et al. Patients’ views and readmissions 1 year after involuntary hospitalisation. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:49–54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.052266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iversen KI, Høyer G, Sexton HC. Coercion and patient satisfaction on psychiatric acute wards. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30:504–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoge SK, Lidz CW, Eisenberg M, Gardner W, Monahan J, Mulvey E, et al. Perceptions of coercion in the admission of voluntary and involuntary psychiatric patients. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1997;20:167–81. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(97)00001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Donoghue B, Lyne J, Hill M, Larkin C, Feeney L, O’Callaghan E. Involuntary admission from the patients’ perspective. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:631–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Donoghue B, Lyne J, Hill M, O’Rourke L, Daly S, Larkin C, et al. Perceptions of involuntary admission and risk of subsequent readmission at one-year follow-up: The influence of insight and recovery style. J Ment Health. 2011;20:249–59. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.562263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padmavati R, Thara R, Corin E. A qualitative study of religious practices by chronic mentally ill and their caregivers in South India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2005;51:139–49. doi: 10.1177/0020764005056761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lahariya C, Singhal S, Gupta S, Mishra A. Pathway of care among psychiatric patients attending a mental health institution in central India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:333–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.74308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katsakou C, Marougka S, Garabette J, Rost F, Yeeles K, Priebe S. Why do some voluntary patients feel coerced into hospitalisation? A mixed-methods study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivar Iversen K, Høyer G, Sexton H, Grønli OK. Perceived coercion among patients admitted to acute wards in Norway. Nord J Psychiatry. 2002;56:433–9. doi: 10.1080/08039480260389352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan KA, Burns T. Perceived coercion and the therapeutic relationship: A neglected association? Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:471–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Svindseth MF, Dahl AA, Hatling T. Patients’ experience of humiliation in the admission process to acute psychiatric wards. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61:47–53. doi: 10.1080/08039480601129382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Donoghue B, Roche E, Shannon S, Lyne J, Madigan K, Feeney L. Perceived coercion in voluntary hospital admission. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215:120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenna BG, Simpson AI, Coverdale JH. Outpatient commitment and coercion in New Zealand: A matched comparison study. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2006;29:145–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hannon MJ. Does fear of coercion keep people away from mental health treatment? Evidence from a survey of persons with schizophrenia and mental health professionals. Behav Sci Law. 2003;21:459–72. doi: 10.1002/bsl.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, Elbogen EB. Consumers’ perceptions of the fairness and effectiveness of mandated community treatment and related pressures. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:780–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]