Abstract

BACKGROUND

Level of blood pressure (BP) is strongly associated with cardiovascular (CV) events and mortality. However, it is questionable whether mean BP can fully capture BP-related vascular risk. Increasing attention has been given to the value of visit-to-visit BP variability.

METHODS

We examined the association of visit-to-visit BP variability with mortality, incident myocardial infarction (MI), and incident stroke among 1,877 well-functioning elders in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. We defined visit-to-visit diastolic BP (DBP) and systolic BP (SBP) variability as the root-mean-square error of person-specific linear regression of BP as a function of time. Alternatively, we counted the number of considerable BP increases and decreases (separately; 10mm Hg for DBP and 20mm Hg for SBP) between consecutive visits for each individual.

RESULTS

Over an average follow-up of 8.5 years, 623 deaths (207 from CV disease), 153 MIs, and 156 strokes occurred. The median visit-to-visit DBP and SBP variability was 4.96 mmHg and 8.53 mmHg, respectively. After multivariable adjustment, visit-to-visit DBP variability was related to higher all-cause (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.18 per 1 SD, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.01–1.37) and CV mortality (HR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.05–1.73). Additionally, individuals having more considerable decreases of DBP (≥10mm Hg between 2 consecutive visits) had higher risk of all-cause (HR = 1.13, 95% CI = 0.99–1.28) and CV mortality (HR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.05–1.61); considerable increases of SBP (≥20mm Hg) were associated with higher risk of all-cause (HR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.03–1.36) and CV mortality (HR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.08–1.74).

CONCLUSIONS

Visit-to-visit DBP variability and considerable changes in DBP and SBP were risk factors for mortality in the elderly.

Keywords: blood pressure, blood pressure variability, hypertension, mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction, aged.

Level of blood pressure (BP) is strongly associated with risk of stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and mortality,1–3 and the mean of multiple BP measures over a period of time is used in clinical settings to make treatment decisions. However, it is questionable whether mean BP can fully capture BP-related vascular risk.4 Rate of change in BP has been shown to be related to cardiovascular (CV) events and mortality5–7; however, we previously found no associations between BP slope and outcomes, using data from the Health, Aging, Body Composition (Health ABC) Study.8 Recently, increasing attention has been paid to the value of visit-to-visit BP variability.5–7,9–19 Visit-to-visit BP variability may represent an inability to maintain homeostasis and have adverse effects on the vascular tissues and end-organs, leading to CV diseases and mortality.20,21 Additionally, visit-to-visit BP variability may be a result of intensification of antihypertensive medications or varying adherence to medications. A better understanding of visit-to-visit BP variability in the setting of medication use is especially relevant because the results of the recent Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) may lead to increased medication use among older adults.22

There is a developing body of literature on the association of visit-to-visit BP variability with mortality and CV events, although the findings have been mixed and prior studies have mostly focused on the visit-to-visit variability in systolic BP (SBP). Some researchers found that a higher level of visit-to-visit SBP variability was associated with an increased risk of mortality,5,11,13,16 stroke,6,10,15 and MI,10 whereas others found no association of visit-to-visit SBP variability with mortality7 or stroke.5,11

Different definitions of visit-to-visit BP variability have been utilized in previous studies; many have used SD or coefficient of variation to define visit-to-visit BP variability.5,10,12,14–16 However, neither of these 2 definitions distinguishes systematic changes in BP over time (e.g., slope) from true variation in BP.7 Moreover, some previous studies have used selective samples such as patients with treated hypertension,10,12,13 individuals with a history of or risk factors for CV disease,5 and type II diabetic patients,14 which may or may not be generalizable to other subgroups.

In this study, we examined the associations of visit-to-visit diastolic BP (DBP), SBP, and pulse pressure (PP) variability with all-cause and CV mortality in older adults. As a secondary analysis, we investigated the association of visit-to-visit BP variability with incident MI and incident stroke. We also explored whether these associations were modified by antihypertensive medication use. Findings of this study will contribute to our understanding of the potential risks associated with visit-to-visit BP variability.

METHODS

Study population

The Health ABC Study is a longitudinal cohort study designed to examine age-related changes in health and body composition and functional limitations in initially well-functioning older adults. Between March 1997 and July 1998, 3,075 Black and White individuals aged 70–79 years were recruited from a list of Medicare beneficiaries provided by the Health Care Financing Administration at 2 study sites across the United States, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Memphis, Tennessee. Eligibility criteria were (i) free of life-threatening illness, (ii) self-reported ability to walk a quarter of a mile, to climb 10 steps without resting, and to perform basic activities of daily living without assistance, and (iii) no intention to move out the current geographic area for ≥3 years. Details about the Health ABC study have been previously published elsewhere.23,24 All participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the 2 clinical sites and the Data Coordinating Center at the University of California, San Francisco.

The current analyses restricted the study population to participants who had BP measures available in the first 5 annual examinations and did not experience an MI or stroke prior to their fifth clinic visit, leaving a final analytic sample size of 1,877. A flow diagram of participants through each stage of selection based on inclusion criteria is shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes included all-cause and CV mortality; secondary outcomes included incident MI and incident stroke. All outcomes were assessed starting after the fifth annual clinic visit. Participants were censored at the date of last contact or by the end of the follow-up period (30 April 2010 for Memphis and 30 June 2010 for Pittsburgh), whichever came first. All participants had annual visits to clinical centers or telephone contacts every 6 months during which health status was measured and CV outcomes were identified. Deaths were ascertained by review of local obituaries, by reports to the clinical centers by family members, or by means of the semiannual telephone contacts. Diagnoses and cause of death were adjudicated based on interview, review of all hospital records, death certificates, and other support documents by a panel of physicians.

Predictors

DBP and SBP were measured annually and, for each visit, we used the average of 2 measurements by a conventional mercury sphygmomanometer with an appropriately sized cuff, taken in the seated position after 5 minutes of quiet rest. PP was calculated as the difference between SBP and DBP.

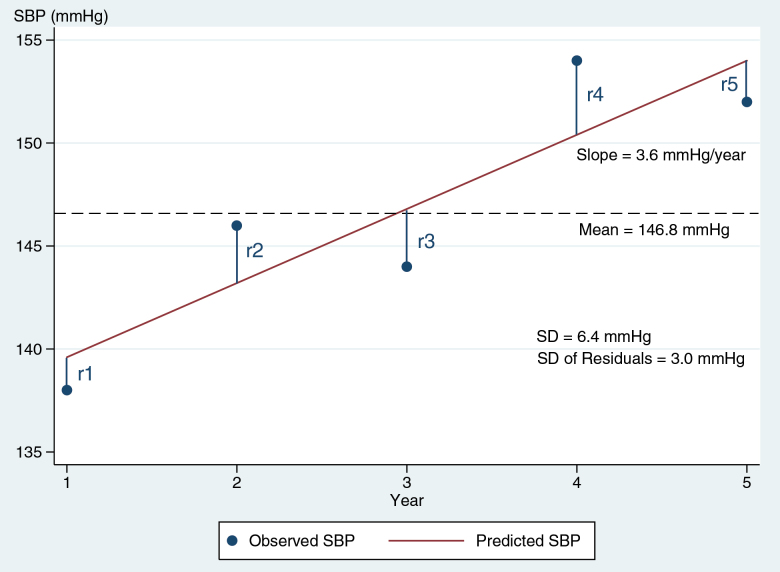

For each participant, mean BP was calculated as the average of the 5 BP measurements taken in the first 5 annual visits; average BP change was calculated as the slope coefficient in the person-specific linear regression of BP on time (in years); visit-to-visit BP variability was calculated as the root-mean-square error (RMSE) of the residuals (i.e., differences between observed BP and predicted BP) from the regression (Figure 1). Three summary measures of BP (mean, change, variability) were calculated separately for DBP, SBP, and PP. Visit-to-visit BP variability was treated as the primary predictor, adjusting for mean BP and average annual BP change.

Figure 1.

Illustration of long-term visit-to-visit DBP variability: the SD of the residuals taken from person-specific linear regression of 5 measures of DBP (residual-mean-square error). Abbreviation: DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

In an alternative approach, we adopted a method from Arnold et al.,25 to classify participants based on presence of episodes of considerable increase or decrease in BP. The goal of this approach was to capture episodes of large changes in BP between visits. More than 10mm Hg change in DBP (20mm Hg for SBP) between consecutive visits were considered episode of considerable change. These cutoffs were chosen based on the distribution of change in BP and clinical relevance (i.e., more than expected by just adding 1 BP lowering medication). For each type of BP, 1 participant could only have 1 considerable change between any of the 2 consecutive visits. We counted the number of considerable increases and decreases in DBP and SBP (separately) and examined its association with outcomes.

Covariates

Sociodemographics included age, race (Black, White), study site (Pittsburgh, Memphis), and education (<high school, high school, >high school). Behavioral characteristics included smoking status (current, former, never), and body mass index defined as body weight (kilograms) divided by height (meters) squared. Clinical measures included fasting serum glucose (mg/dl), fasting high-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl), and fasting plasma triglycerides (mg/dl). Chronic health conditions included hypertension, CV disease (including coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease), heart failure, and diabetes (assessed by self-report, medication use, or a positive diagnosis by fasting blood glucose level or oral glucose tolerance test). We used information of antihypertensive medication use in years 1, 2, 3, and 5 (measures were unavailable in year 4) to classify participants into 3 categories: consistent users (using medication in all 4 visits), inconsistent users (using medication in some visits but not in others), or nonusers (not using medication in any of the 4 visits).

Statistical analyses

We compared baseline characteristics of participants across high and low visit-to-visit DBP variability (≥ and <median), using a t-test for continuous variables and a chi-squared test for categorical variables. We also compared baseline measures across types of antihypertensive medication use (consistent users, inconsistent users, nonusers) using chi-squared tests and analysis of variance.

We used Cox models26 to identify the associations of visit-to-visit BP variability (measured by RMSE) with all-cause and CV mortality, incident MI and incident stroke, adjusting for mean BP, and average annual BP change. Then, sociodemographics (age, sex, race, education), behavioral measures (smoking status, body mass index), clinical measures (fasting serum glucose, fasting plasma high-density lipoprotein, fasting plasma low-density lipoprotein, fasting plasma triglycerides), and antihypertensive medication use were entered into the Cox models. We used 2 approaches to determine whether the associations differed across 3 types of antihypertensive medication users. First, we created interaction terms between visit-to-visit BP variability and antihypertensive medication use and tested using the likelihood ratio test. As a secondary analysis, we stratified the analyses by antihypertensive medication use categories (consistent, inconsistent, never).

Additionally, we used Cox models to examine the relation of number of considerable increases and decreases in DBP and SBP (separately) with outcomes, adjusting for BP mean and average annual BP change as well as confounders documented above.

As a sensitivity analysis, we additionally adjusted for SBP level in the analyses of the association of visit-to-visit DBP and PP variability with outcomes.

All analyses were performed using Stata 13.1.27

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The median and mean of the visit-to-visit variability of DBP across 5 annual visits were 4.98mm Hg and 5.45mm Hg, respectively. Individuals in the higher half of visit-to-visit DBP variability were more likely to be of Black race and had fewer years of education (Table 1). Compared with individuals with lower visit-to-visit DBP variability, those with higher visit-to-visit DBP variability had lower triglycerides, and greater prevalence of CV disease and hypertension. Additionally, those with higher visit-to-visit DBP variability had higher mean DBP and SBP over 5 years, and greater visit-to-visit SBP and PP variability. The median and mean of visit-to-visit SBP variability were 8.53mm Hg and 9.56mm Hg, respectively. Sample characteristics stratified by high and low visit-to-visit SBP variability (cutoff: median) were presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics across by visit-to-visit variability of DBP (≤ vs. > median = 4.96mm Hg)

| Characteristics | ≤Median (low) | >Median (high) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or N (%) | P valuea | ||

| Site | <0.001 | ||

| Memphis | 533 (56.9) | 403 (43.0) | |

| Pittsburgh | 405 (43.3) | 536 (57.1) | |

| Age (years) | 73.3±2.8 | 73.6±2.8 | <0.05 |

| Women | 511 (54.6) | 494 (52.7) | 0.42 |

| Black | 305 (32.6) | 388 (41.4) | <0.001 |

| Education | <0.01 | ||

| <High school | 177 (18.9) | 236 (25.2) | |

| High school graduate | 337 (36.0) | 289 (30.8) | |

| Postsecondary | 424 (45.3) | 413 (44.0) | |

| Smoking status | 0.21 | ||

| Never | 456 (48.7) | 419 (44.7) | |

| Current smoker | 69 (7.4) | 79 (8.4) | |

| Former smoker | 412 (44.0) | 440 (46.9) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.39 | ||

| <25 | 287 (30.7) | 306 (32.6) | |

| 25–30 | 421 (45.0) | 392 (41.8) | |

| >30 | 230 (24.6) | 241 (25.7) | |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 71.1±10.1 | 71.1±12.6 | 0.89 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 133.6±19.0 | 136.0±20.9 | <0.05 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 102.2±30.8 | 102.2±29.5 | 0.99 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 54.4±16.7 | 54.0±16.8 | 0.64 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 122.1±35.4 | 121.5±34.4 | 0.73 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 142.3±77.4 | 136.2±80.5 | 0.09 |

| Heart failure | 16 (1.7) | 14 (1.5) | 0.18 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 144 (15.4) | 176 (18.8) | <0.05 |

| Diabetes | 122 (13.0) | 124 (13.2) | 0.90 |

| Hypertension | 414 (44.2) | 471 (50.2) | <0.05 |

| Antihypertensive medication use | <0.01 | ||

| Nonusers | 352 (37.6) | 274 (29.2) | |

| Consistent users | 401 (42.8) | 449 (47.9) | |

| Inconsistent users | 185 (19.8) | 216 (23.0) | |

| 5yr intraindividual mean DBP (mm Hg)b | 71.3±7.9 | 71.8±8.8 | 0.14 |

| 5yr intraindividual slope DBP (mm Hg/year)b | 0.2±2.7 | 0.4±3.0 | 0.07 |

| 5yr intraindividual variability SBPb | 8.1±3.9 | 11.1±5.9 | <0.001 |

| 5yr intraindividual mean SBP (mm Hg)b | 134.1±15.2 | 137.2±16.0 | <0.001 |

| 5yr intraindividual slope SBP (mm Hg/year)b | 0.7±4.9 | 0.9±5.2 | 0.60 |

| 5yr intraindividual variability PPb | 8.5±5.0 | 9.9±6.0 | <0.001 |

| 5yr intraindividual mean PP (mm Hg)b | 62.8±13.3 | 65.3±14.2 | <0.001 |

| 5yr intraindividual slope PP (mm Hg/year)b | 0.6±3.8 | 0.5±4.5 | 0.53 |

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PP, pulse pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

aTwo-sample t-test for continuous variables, chi-squared test for categorical variables.

bRegressing DBP, SBP, or PP on time (in years) for every participant over the first five years (5 blood pressure measures).

Over the first 5 years, 626 (33.4%) participants were classified as nonusers (not using antihypertensive medication in any of the 4 visits), 850 (45.3%) as consistent users (using antihypertensive medication in all 4 visits), and 401 (21.4%) as inconsistent users (using antihypertensive medication in some visits but not in others). Consistent users were most likely to be women and of Black race and had the lowest education level (Supplementary Table S2). Compared with nonusers and inconsistent users, consistent users had higher DBP, SBP, fasting glucose, and triglycerides at baseline. Chronic conditions, including heart failure, CV disease, hypertension, and diabetes, were also more prevalent in consistent users compared to nonusers and inconsistent users.

BP variability and outcomes

Over an average 8.5 years of follow-up, 153 incident MIs, 156 incident strokes, 623 deaths, and 207 deaths from CV diseases occurred. After adjustment for DBP mean and average annual DBP change, higher visit-to-visit DBP variability was significantly associated with increased risk of all the mortality outcomes, and the associations remained significant for all-cause mortality and CV mortality in fully adjusted models (Table 2). Higher visit-to-visit SBP variability was significantly associated with increased risk of all the mortality outcomes, although the associations no longer reached statistical significance in fully adjusted models. Greater visit-to-visit PP variability was significantly associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality. Inclusion of SBP level as an adjustment covariate did not change the associations of visit-to-visit PP variability with outcomes (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 2.

Associations of visit-to-visit blood pressure variability with MI, incident stroke, and mortality

| MI | Stroke | All-cause mortality | CV mortality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure | |||||||||

| Variability | Adjusteda | 1.03 | 0.76–1.40 | 1.32 | 0.99–1.75 | 1.31*** | 1.14–1.51 | 1.54*** | 1.22–1.95 |

| Fully adjustedb | 1.01 | 0.73–1.40 | 1.17 | 0.87–1.59 | 1.18* | 1.01–1.37 | 1.35* | 1.05–1.73 | |

| Systolic blood pressure | |||||||||

| Variability | Adjusteda | 1.12 | 0.84–1.49 | 1.16 | 0.88–1.54 | 1.22** | 1.06–1.41 | 1.36** | 1.09–1.72 |

| Fully adjustedb | 1.10 | 0.81–1.49 | 1.09 | 0.80–1.48 | 1.11 | 0.95–1.29 | 1.20 | 0.94–1.54 | |

| Pulse pressure | |||||||||

| Variability | Adjusteda | 1.04 | 0.89–1.21 | 1.05 | 0.90–1.23 | 1.13** | 1.05–1.22 | 1.17* | 1.03–1.32 |

| Fully adjustedb | 1.07 | 0.90–1.27 | 0.99 | 0.83–1.17 | 1.11* | 1.02–1.20 | 1.13 | 0.99–1.28 | |

Per 1 SD difference of visit-to-visit blood pressure variability. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction.

aEstimates adjusted for blood pressure mean and blood pressure slope.

bEstimates adjusted for demographic measures (age, gender, race, education), clinical measures (fasting serum glucose, fasting plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting plasma triglycerides), antihypertensive medication use (never, consistent, inconsistent), and health behaviors (current smoking status, former smoking status, body mass index), blood pressure mean, and blood pressure slope.

Greater visit-to-visit DBP variability was associated with higher risk of all-cause and CV mortality and higher visit-to-visit SBP variability was independently associated with higher risk of CV mortality in consistent users (Table 3). Additionally, higher visit-to-visit SBP and PP variability was significantly associated with all-cause mortality in nonusers. Moreover, greater visit-to-visit PP variability was related to higher risk of mortality outcomes among inconsistent users. The associations of visit-to-visit DBP and SBP variability with the mortality outcomes appeared less pronounced in inconsistent users, although none of the differences were statistically significant. Results were virtually unchanged when SBP level was additionally adjusted (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 3.

Associations of visit-to-visit blood pressure variability with mortality across antihypertensive medication use (stratified analyses)

| All-cause mortality | CV mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Nonusers (n = 626) | ||||

| DBP variability | 1.21 | 0.88–1.66 | 1.32 | 0.68–2.55 |

| SBP variability | 1.52* | 1.05–2.20 | 1.60 | 0.75–3.41 |

| PP variability | 1.36*** | 1.15–1.62 | 1.17 | 0.79–1.74 |

| Consistent users (n = 850) | ||||

| DBP variability | 1.26* | 1.01–1.56 | 1.47* | 1.06–2.04 |

| SBP variability | 1.14 | 0.92–1.41 | 1.47* | 1.08–2.01 |

| PP variability | 1.00 | 0.89–1.12 | 1.00 | 0.84–1.21 |

| Inconsistent users (n = 401) | ||||

| DBP variability | 1.05 | 0.77–1.42 | 1.35 | 0.82–2.23 |

| SBP variability | 0.95 | 0.81–1.11 | 0.69 | 0.41–1.18 |

| PP variability | 1.17* | 1.00–1.37 | 1.30* | 1.02–1.65 |

Per 1 SD difference of visit-to-visit blood pressure variability. Diastolic blood pressure, systolic blood pressure, and pulse pressure were analyzed separately. All estimates adjusted for demographic measures (age, gender, race, education), clinical measures (fasting serum glucose, fasting plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting plasma triglycerides), and health behaviors (current smoking status, former smoking status, body mass index), blood pressure mean, and blood pressure slope. Separate analyses were conducted for diastolic blood pressure and systolic blood pressure. P-value for interaction: DBP variability × medication use for all-cause mortality = 0.99; DBP variability × medication use for CV mortality = 0.99; SBP variability × medication use for all-cause mortality = 0.21; SBP variability × medication use for CV mortality = 0.06; PP variability × medication use for all-cause mortality = 0.02; PP variability × medication use for CV mortality = 0.98. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, hazard ratio; PP, pulse pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

BP stability and outcomes

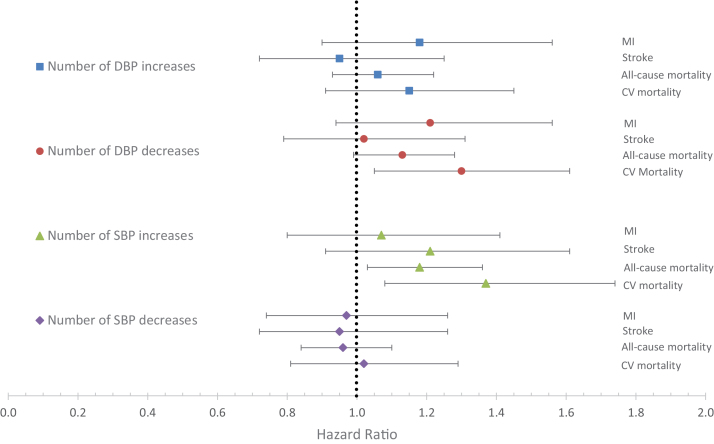

Participants who had more episodes of considerable decreases of DBP appeared to have greater risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.13, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.99–1.28) and CV mortality (HR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.05–1.61) (Figure 2). Associations for MI and stroke were similar to those of mortality but were not significant. In addition, more episodes of considerable increases of SBP were significantly associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.03–1.36) and CV mortality (HR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.08–1.74) in fully adjusted models.

Figure 2.

Association of considerable DBP and SBP changes (separately) with incident MI, incident stroke, all-cause mortality, and CV mortality. Estimates represent the hazard ratio per considerable change in blood pressure; a considerable change was an increase or decrease of at least 10mm Hg diastolic or 20mm Hg systolic between visits. Estimates adjusted for demographic measures (age, gender, race, education), clinical measures (fasting serum glucose, fasting plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting plasma triglycerides), antihypertensive medication use (never, consistent, inconsistent), and health behaviors (current smoking status, former smoking status, body mass index), blood pressure mean, and blood pressure slope. Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

DISCUSSION

In a large-scale prospective study of well-functioning older adults, we found evidence that higher levels of visit-to-visit DBP variability, as captured by the RMSE, were independently associated with increased risk of all-cause and CV mortality. Additionally, we found that older adults having more considerable decreases in DBP (10mm Hg per year) or considerable increases in SBP (20mm Hg per year) had higher risk of mortality outcomes. Although most recommendations for the treatment of hypertension among older adults emphasize optimal SBP targets, our findings highlight the importance of visit-to-visit DBP variability and considerable DBP decrease.

The association of long-term visit-to-visit BP variability with increased all-cause and CV mortality revealed in our study is consistent with previous research.5,11,13,14 Hastie et al.13 showed that both visit-to-visit DBP and SBP variability, quantified by the average real variability, were associated with increased mortality risk in a cohort of hypertensive patients. In the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) study, Poortvliet et al.5 found higher visit-to-visit DBP and SBP variability, defined by the SD and coefficient of variation, were independently predictive of all-cause and CV mortality. In a recent investigation of 3,852 community-dwelling older adults, Suchy-Dicey et al.11 showed that increased visit-to-visit SBP variability, captured by the RMSE, was associated with higher mortality, after controlling for mean SBP and change of SBP. More recently, Muntner et al.12 found high levels of visit-to-visit SBP variability, defined by the SD, were associated with increased risk of mortality among trial patients with hypertension and at least one other risk factor for CV disease. Two large meta-analyses have reported a significant association of visit-to-visit BP variability with all-cause and CV mortality.18,19 However, as indicated in both studies, substantial variation exists in measurement of visit-to-visit BP variability and this lack of standardization limits the comparability among research. In addition, among analyzed studies, relatively few quantified visit-to-visit BP variability using RMSE, which is arguably a better measurement of visit-to-visit BP variability than SD and coefficient of variation.

There have been contradictory findings regarding the associations of visit-to-visit BP variability with MI and stroke in older adults. In the present study, no strong association was present between BP variability and MI or stroke, which is in line with several previous studies.5,6 For example, Shimizu et al.28 found no association between visit-to-visit BP variability, defined by the RMSE, and stroke, adjusting for BP mean and slope. In the PROSPER study, neither visit-to-visit DBP nor SBP variability was associated with stroke among participants with a history of or risk factors for CV disease.5 In contrast, some studies have indicated that visit-to-visit BP variability is a predictor of stroke,6,10,15 MI,12 and coronary heart disease.29 In addition, 2 recent meta-analyses showed modest associations of visit-to-visit BP variability with stroke and coronary heart disease.18,19

One reason for these conflicting results may be that visit-to-visit BP variability has been defined differently and previous studies mostly used SD of BP to define visit-to-visit BP variability. Because SD of BP reflects different sources of variation around the mean level such as BP variability and systematic change of BP over time, defining visit-to-visit BP variability as SD of BP could inflate the predictive power of BP variability and confound which dimension of CV dynamics is driving the effects (i.e., change vs. variability). This distinction is important given that BP slope has been recently shown to be associated with CV events and mortality.5–7 For example, Shimbo et al.6 found a steeper slope of SBP was related to an increased risk of stroke in postmenopausal women. In an elderly primary care patient cohort, Gao et al.7 identified a U-shaped relationship between rate of change in BP and death, with little or no change having the lowest mortality. In contrast, the definition of BP variability used in our study allows us to distinguish variation of BP from BP slope, and thus to examine the incremental value of visit-to-visit BP variability in addition to mean BP and BP slope. Future research should consider using RMSE, a methodologically more pure measure, rather than SD, which conflates systematic/linear changes and variability, to define visit-to-visit BP variability, especially if linear change of BP over time is present.

The physiological mechanisms by which visit-to-visit BP variability influences mortality are not well understood and merit further investigation. High visit-to-visit BP variability could represent an inability to maintain hemodynamic homeostasis and may have negative impacts on the vascular system and end-organs, leading to mortality.20,21 Additionally, increased visit-to-visit BP variability may be a marker of low artery elasticity, leading to functional alterations in the aorta and other large vessels.30 Moreover, subclinical inflammation, which was found to be related to visit-to-visit BP variability,31 may also play a role in the association of BP variability and adverse outcomes.

In this study, we also found a considerable decrease in DBP was associated with increased mortality risk. One explanation is that a large drop in DBP and the resultant low DBP level may lead to impaired organ perfusion, especially the heart, which is only perfused during diastole.32 In contrast to BP slope, which measures an average rate of BP change over multiple occasions, considerable change in BP between 2 consecutive visits reflects change in BP over relatively short intervals and may capture a different aspect of BP-related mortality risk.

Several investigators have proposed that noncompliance to antihypertensive medications accounts for the association of visit-to-visit BP variability with adverse outcomes.29,33 Findings of this study suggest this is not a complete explanation because there was evidence for associations of visit-to-visit SBP variability with mortality among medication nonusers. In addition, the association of visit-to-visit BP variability with mortality was less pronounced among inconsistent users—whom we would expect to have high medication-driven visit-to-visit BP variability—compared to consistent users and nonusers. These findings demonstrate the importance of accounting for the changes in treatment regimens rather than simply focusing on the treatment status at a single time point.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, we were unable to determine whether visit-to-visit BP variability was causally associated with mortality or it was merely a marker for some underlying risk factors for mortality. A better understanding of the role of visit-to-visit BP variability can elucidate whether new therapies directly addressing high visit-to-visit BP variability might reduce mortality risk. Second, information about antihypertensive medication use was only available in years 1, 2, 3, and 5; more frequent measures of medication use could better classify participants. Finally, our definitions of variability are based upon annual measures of BP; more frequent assessments might have improved our phenotyping of variability and thus strengthened our associations (e.g., measurement burst design).

In conclusion, our findings highlight the importance of evaluating long-term variability and episodes of considerable changes in both DBP and SBP in geriatric care. Older adults who do not maintain a stable level of BP over time may be at increased risk of mortality.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary materials are available at American Journal of Hypertension (http://ajh.oxfordjournals.org).

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Health ABC Study was supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) Contracts N01-AG-6-2101; N01-AG-6-2103; N01-AG-6-2106; NIA grant R01-AG028050, and NINR grant R01-NR012459, and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging. Additional support for this research was provided by National Institute on Aging (K01AG039387, R01AG46206).

REFERENCES

- 1. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R; Prospective Studies Collaboration Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002; 360:1903–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Psaty BM, Furberg CD, Kuller LH, Cushman M, Savage PJ, Levine D, O’Leary DH, Bryan RN, Anderson M, Lumley T. Association between blood pressure level and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and total mortality: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161:1183–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Staessen JA, Gasowski J, Wang JG, Thijs L, Den Hond E, Boissel JP, Coope J, Ekbom T, Gueyffier F, Liu L, Kerlikowske K, Pocock S, Fagard RH. Risks of untreated and treated isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet 2000; 355:865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rothwell PM. Limitations of the usual blood-pressure hypothesis and importance of variability, instability, and episodic hypertension. Lancet 2010; 375:938–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poortvliet RK, Ford I, Lloyd SM, Sattar N, Mooijaart SP, de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG, Jukema JW, Packard CJ, Gussekloo J, de Ruijter W, Stott DJ. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular risk in the PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER). PLoS One 2012; 7:e52438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shimbo D, Newman JD, Aragaki AK, LaMonte MJ, Bavry AA, Allison M, Manson JE, Wassertheil-Smoller S. Association between annual visit-to-visit blood pressure variability and stroke in postmenopausal women: data from the Women’s Health Initiative. Hypertension 2012; 60:625–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gao S, Hendrie HC, Wang C, Stump TE, Stewart JC, Kesterson J, Clark DO, Callahan CM. Redefined blood pressure variability measure and its association with mortality in elderly primary care patients. Hypertension 2014; 64:45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Odden MC, Wu C, Shlipak MG, Psaty BM, Katz R, Applegate WB, Harris T, Newman AB, Peralta CA. Blood pressure trajectory, gait speed, and outcomes: the Health Aging and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, published online 3 May 2016 (doi:10.1093/gerona/glw076). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rothwell PM. Does blood pressure variability modulate cardiovascular risk? Curr Hypertens Rep 2011; 13:177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, O’Brien E, Dobson JE, Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet 2010; 375:895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Suchy-Dicey AM, Wallace ER, Mitchell SV, Aguilar M, Gottesman RF, Rice K, Kronmal R, Psaty BM, Longstreth WT., Jr Blood pressure variability and the risk of all-cause mortality, incident myocardial infarction, and incident stroke in the cardiovascular health study. Am J Hypertens 2013; 26:1210–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muntner P, Whittle J, Lynch AI, Colantonio LD, Simpson LM, Einhorn PT, Levitan EB, Whelton PK, Cushman WC, Louis GT, Davis BR, Oparil S. Visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure and coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163:329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hastie CE, Jeemon P, Coleman H, McCallum L, Patel R, Dawson J, Sloan W, Meredith P, Jones GC, Muir S, Walters M, Dominiczak AF, Morrison D, McInnes GT, Padmanabhan S. Long-term and ultra long-term blood pressure variability during follow-up and mortality in 14,522 patients with hypertension. Hypertension 2013; 62:698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hsieh YT, Tu ST, Cho TJ, Chang SJ, Chen JF, Hsieh MC. Visit-to-visit variability in blood pressure strongly predicts all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 5·5-year prospective analysis. Eur J Clin Invest 2012; 42:245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brickman AM, Reitz C, Luchsinger JA, Manly JJ, Schupf N, Muraskin J, DeCarli C, Brown TR, Mayeux R. Long-term blood pressure fluctuation and cerebrovascular disease in an elderly cohort. Arch Neurol 2010; 67:564–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muntner P, Shimbo D, Tonelli M, Reynolds K, Arnett DK, Oparil S. The relationship between visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure and all-cause mortality in the general population: findings from NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Hypertension 2011; 57:160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tai C, Sun Y, Dai N, Xu D, Chen W, Wang J, Protogerou A, van Sloten TT, Blacher J, Safar ME, Zhang Y, Xu Y. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit systolic blood pressure variability: a meta-analysis of 77,299 patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2015; 17:107–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diaz KM, Tanner RM, Falzon L, Levitan EB, Reynolds K, Shimbo D, Muntner P. Visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension 2014; 64:965–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stevens SL, Wood S, Koshiaris C, Law K, Glasziou P, Stevens RJ, McManus RJ. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016; 354:i4098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Diaz KM, Veerabhadrappa P, Kashem MA, Feairheller DL, Sturgeon KM, Williamson ST, Crabbe DL, Brown MD. Relationship of visit-to-visit and ambulatory blood pressure variability to vascular function in African Americans. Hypertens Res 2012; 35:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mancia G, Parati G. The role of blood pressure variability in end-organ damage. J Hypertens Suppl 2003; 21:S17–S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, Reboussin DM, Rahman M, Oparil S, Lewis CE, Kimmel PL, Johnson KC, Goff DC, Fine LJ, Cutler JA, Cushman WC, Cheung AK, Ambrosius WT. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Newman AB, Haggerty CL, Goodpaster B, Harris T, Kritchevsky S, Nevitt M, Miles TP, Visser M; Health Aging And Body Composition Research Group Strength and muscle quality in a well-functioning cohort of older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51:323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rooks RN, Simonsick EM, Miles T, Newman A, Kritchevsky SB, Schulz R, Harris T. The association of race and socioeconomic status with cardiovascular disease indicators among older adults in the health, aging, and body composition study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002; 57:S247–S256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arnold AM, Newman AB, Cushman M, Ding J, Kritchevsky S. Body weight dynamics and their association with physical function and mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010; 65:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables (with discussion). J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1972; 34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13 [computer program]. StataCorp LP: College Station, TX, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shimizu Y, Kato H, Lin CH, Kodama K, Peterson AV, Prentice RL. Relationship between longitudinal changes in blood pressure and stroke incidence. Stroke 1984; 15:839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grove JS, Reed DM, Yano K, Hwang LJ. Variability in systolic blood pressure–a risk factor for coronary heart disease? Am J Epidemiol 1997; 145:771–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shimbo D, Shea S, McClelland RL, Viera AJ, Mann D, Newman J, Lima J, Polak JF, Psaty BM, Muntner P. Associations of aortic distensibility and arterial elasticity with long-term visit-to-visit blood pressure variability: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Hypertens 2013; 26:896–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Poortvliet RK, Lloyd SM, Ford I, Sattar N, de Craen AJ, Wijsman LW, Mooijaart SP, Westendorp RG, Jukema JW, de Ruijter W, Gussekloo J, Stott DJ. Biological correlates of blood pressure variability in elderly at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens 2015; 28:469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Muller M, Smulders YM, de Leeuw PW, Stehouwer CD. Treatment of hypertension in the oldest old: a critical role for frailty? Hypertension 2014; 63:433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krakoff LR. Fluctuation: does blood pressure variability matter? Circulation 2012; 126:525–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]