Abstract

We recently isolated from Dictyostelium discoideum cells a DNA-binding protein, CbfA, that interacts in vitro with a regulatory element in retrotransposon TRE5-A. We have generated a mutant strain that expresses CbfA at <5% of the wild-type level to characterize the consequences for D. discoideum cell physiology. We found that the multicellular development program leading to fruiting body formation is highly compromised in the mutant. The cells cannot aggregate and stay as a monolayer almost indefinitely. The cells respond properly to prestarvation conditions by expressing discoidin in a cell density-dependent manner. A genomewide microarray-assisted expression analysis combined with Northern blot analyses revealed a failure of CbfA-depleted cells to induce the gene encoding aggregation-specific adenylyl cyclase ACA and other genes required for cyclic AMP (cAMP) signal relay, which is necessary for aggregation and subsequent multicellular development. However, the cbfA mutant aggregated efficiently when mixed with as few as 5% wild-type cells. Moreover, pulsing cbfA mutant cells developing in suspension with nanomolar levels of cAMP resulted in induction of acaA and other early developmental genes. Although the response was less efficient and slower than in wild-type cells, it showed that cells depleted of CbfA are able to initiate development if given exogenous cAMP signals. Ectopic expression of the gene encoding the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A restored multicellular development of the mutant. We conclude that sensing of cell density and starvation are independent of CbfA, whereas CbfA is essential for the pattern of gene expression which establishes the genetic network leading to aggregation and multicellular development of D. discoideum.

Dictyostelium discoideum is a social amoeba that lives in soil and feeds on bacteria. When the cells sense environmental conditions unfavorable for vegetative growth, they start to communicate with each other by means of extracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP). Individual cells move toward higher concentrations of cAMP and produce cAMP themselves, which is secreted and serves to relay the signal in the aggregation field. Oscillatory secretion and perception of extracellular cAMP guide the cells into aggregation centers, in which they cooperate to form fruiting bodies consisting of stalk cells that support a mass of dormant spores (2, 23).

As the density of growing cells increases, aggregation competence is acquired in response to secreted quorum-sensing proteins referred to as prestarvation factor (PSF) and conditioned-medium factor (CMF) (7). The PSF protein induces the expression of a subset of early developmental genes, such as the extracellular matrix discoidin proteins and the cAMP receptor CAR1 (8, 32). Extracellular accumulation of PSF also induces the expression of the protein kinase YakA, which interrupts the cell cycle and releases the translation block from the mRNA of the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (PKA-C) (35, 36). CMF is not secreted by growing cells but is rapidly released when the cells starve (21). CMF is an 80-kDa protein that modulates signal transduction from CAR1 to its downstream effector, the aggregation-specific adenylyl cyclase ACA. When CMF concentrations are low, ligand-induced activation of CAR1 cannot be transmitted to ACA even in the presence of high cAMP concentrations (3, 4). Thus, the cells sense starvation of neighboring cells as a function of the CMF level and can proceed to aggregate (17).

CAR1 is a typical serpentine receptor that couples via trimeric G proteins to several intracellular effectors, including adenylyl cyclase, guanylyl cyclase, and phospholipase C (23, 29). The gene encoding the activatable adenylyl cyclase ACA, acaA, is rapidly induced when the cells start to respond to extracellular cAMP (30). Activation of ACA is complex and requires at least the Gβγ complex of heterotrimeric G proteins, the cytosolic regulator of adenylyl cyclase (CRAC), and components of the Ras pathway (2, 23, 29). ACA activity is the major source of cAMP produced in early stages of D. discoideum development (30). Most cAMP is secreted in order to relay the cAMP signal to nearby aggregation-competent cells.

PKA is an essential regulator of all stages of D. discoideum development (14, 25, 31, 33). PKA is a heterodimeric protein consisting of a catalytic and a regulatory subunit. Cytoplasmic cAMP binds to the regulatory subunit of PKA, which releases the catalytic subunit to phosphorylate downstream substrates that lead to alteration in gene expression (40). Extracellular cAMP is degraded by the product of pdsA, a cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase, whose expression increases dramatically following the initiation of development (13). This extracellular cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase is controlled by a specific inhibitor (PDI) whose expression is regulated in response to cAMP (15). Intracellular cAMP is broken down by the phosphodiesterase RegA (34). The concerted action of many gene products involved in the generation and perception of periodic nanomolar cAMP waves, including ACA, CAR1, PkaC, PdsA, RegA, and others, establishes a positive feedback loop that leads to the activation of genes required for aggregation and subsequent multicellular development. Inactivation of any gene involved in this regulatory network will result in mutants that cannot aggregate, and suppression of the aggregation block with genes involved in the autofeedback loop can be used to dissect the components of these regulatory pathways.

Genomewide DNA microarray analysis of expression profiles is a powerful tool that extends our knowledge of the complex gene networks that regulate D. discoideum development (19, 20, 24, 39). Particularly helpful are genomewide comparative studies of wild-type cells versus mutant cells in which a single known developmental gene is disrupted (19, 24).

Retrotransposons are autonomous genetic entities that can be amplified and inserted at different chromosomal locations in their hosts (11). Active retrotransposons are permanent sources of insertion mutagenesis. Thus, in compact genomes like that of D. discoideum, retrotransposons must follow strategies to avoid disruption of host genes upon retrotransposition (45). One such strategy is the specific recognition of regions flanking tRNA genes as integration sites (45). Studies of the tRNA gene-targeting retrotransposon TRE5-A has led to the isolation of a host-encoded protein that binds specifically to a DNA sequence at the 3′ end of TRE5-A, the C module (16, 18). This protein was named C-module-binding factor (CMBF). We have now changed the name of CMBF to CbfA in order to avoid confusion with CMF (conditioned-medium factor) and to conform to accepted Dictyostelium nomenclature. The DNA-binding properties of CbfA have been analyzed in some detail, and the CbfA-encoding gene, cbfA, has been isolated (18). The CbfA protein, as deduced from a recently revised version of the cbfA gene (GenBank accession no. AF052006), consists of 1,000 amino acids and contains a conserved “carboxy-terminal jumonji” domain implicated in chromatin remodeling (10), three unusual zinc fingers, and an AT hook that is required to bind to the C module in vitro (18).

The C module of retrotransposon TRE5-A serves as a promoter for the transcription of TRE5-A antisense RNAs, but the role of these antisense RNAs in TRE5-A retrotransposition is still obscure. We therefore attempted to generate CbfA-depleted mutants in order to better understand the role of CbfA. We have not been able to isolate strains in which cbfA is deleted by conventional gene replacement approaches, perhaps because it is essential for growth, but we have been able to generate mutants that express CbfA at levels <5% that of wild-type cells by introducing a partially suppressed amber translational stop codon (44). Preliminary analyses of the phenotype of cbfAam mutant cells revealed defects in growth and development (44) and also in TRE5-A retrotransposition (unpublished data). We have now characterized the consequences of CbfA depletion for D. discoideum development by using a combination of genomewide DNA microarray analyses and Northern hybridizations. Although cbfAam cells show a prestarvation response by inducing discoidin expression in a cell density-dependent manner, they do not induce acaA when starved on filters, which can account for their failure to aggregate or form multicellular structures. However, exposure of the mutant cells to artificial extracellular cAMP pulses induced the early genes, including acaA. Mixing cbfAam cells with a few wild-type cells also rescued development of the mutant cells, indicating that the block in morphogenesis occurs after the prestarvation response but before the cAMP positive feedback loop is established.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

D. discoideum cell culture and development.

D. discoideum AX2, AX4, and cbfAam mutant cells (strain JH.D) (44) were grown in shaken cultures either in liquid HL5 medium or in association with Klebsiella planticola bacteria. Food bacteria were prepared as proposed by Clarke et al. (9). Multicellular development of D. discoideum cells was monitored on phosphate-buffered agar plates or on black filters (37). To study gene expression during development, 5 × 107 D. discoideum cells were spread on black nitrocellulose filters (AABP04700; 47-mm diameter; Millipore) and allowed to develop for the time periods indicated in the figures. The cells were then washed from the filters using phosphate buffer and collected by centrifugation. Aliquots corresponding to 2 × 107 cells were stored as pellets at −80°C. Frozen cells were used to extract total RNA as described below.

Expression vector construction and complementation studies.

Expression plasmids were transformed into cbfAam cells, and stable transformants were selected in HL5 medium containing 5 μg of G418/ml. A nearly full-length cbfA cDNA was reconstructed using a combination of cloned and PCR-amplified genomic DNA and cDNA fragments. The cDNA was inserted into the KpnI restriction site of vector pDXA-3H (26) to create the expression vector pDXA-rCbfA. The protein product derived from this vector, named recombinant CbfA (rCbfA), was identical to authentic CbfA protein except that it lacked the two C-terminal isoleucine residues. Control cells were transformed with empty pDXA-3H vector. The pkaC cDNA was either expressed from its endogenous promoter (plasmid p188) (1) or under the control of the constitutively active act6 promoter (plasmid p332) (12).

Induction of cAMP-induced gene expression by cAMP pulses.

D. discoideum AX2, AX4, and cbfAam cells were grown to densities of 3 × 106/ml in axenic cultures. The cells were washed and adjusted to 2 × 107/ml in phosphate buffer. The cultures were shaken at 150 rpm at 22°C. cAMP was added at a 30 nM final concentration at 6-min intervals, starting 2 h after the cells were washed. After 6 h, a single pulse of 300 μM cAMP followed. Aliquots of 2 × 107 cells were collected and frozen as cell pellets at −80°C for further use.

Northern blots.

DNA probes specific for several developmental genes were generated by PCR using DNA sequence information from GenBank entries. The following genes were used for hybridization experiments: acaA (L05499), carA (M21824), csaA (X66483), pkaC (M38703), lagC (U09478), and cotB (M26238). The D. discoideum histone H3 gene (hstC) (6) was used as a loading control on Northern blots. Information on genes SLJ247 and SSD449 was obtained from the Dictyostelium genome project (http://dicty.sdsc.edu). PCR fragments used for hybridization experiments were purified from agarose gels using the QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (QIAGEN). DNA fragments were verified by DNA sequencing using the PCR primers. 32P-labeled probes were generated with the PCR primer complementary to the respective mRNA sequence by using the Taq Cyclist DNA Sequencing kit from Stratagene. A 32P-labeled probe specific for discoidin I was prepared by nick translation (42).

Total RNA was prepared from 2 × 107 frozen cells using the RNeasy Mini kit from QIAGEN; 40 μg of total RNA was separated in denaturing gels, and RNAs were blotted onto Hybond-N membranes. Radioactive probes were hybridized to immobilized RNA at 42°C overnight in 50% formamide-5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-1% sodium dodecyl sulfate-1× Denhardt's solution. The blots were washed for 30 min at ambient temperature in 2× SSC and for 30 min at 65°C in 2× SSC-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate.

The primers used to generate PCR probes were as follows: acaA-01, GTTCATCCTATGGTATGAAATTGG; aca-02, GTAGTGAATGAGCCAATTTCACCC; arA-01, CCAGCCAATGAAACATCATTGG; carA-02, GATGATGATAAAGAAGATGAAGATG; csaA-01, CATTACAGGTACTGGATTTACAG; csaA-02, CCATTGTGAGGTGCTTGAGTGAC; pkaC-01, CCACCACCAGTCAATGCAAGAGAAAG; pkaC-02, CATAGAAAGGTGGATAACCTGCCAAC; cotB-01, GGAGTAGTTGTACACCAAGTAGTGGTTTC; cotB-02, CTTATGGGAACCAATCCAGCCACCTTTTGG; lagC-01, CTCAAGATTATGGGGTAGTATAGAC; lagC-02, CCAGTACCGTATGGTGTTGGACATG; SLJ247-01, GTCAGTGGTGAATGTGCCATTGATTTCTC; SLJ247-02, GGATGATCCACTTCCTGTACCACTTCC; SSD449-01, ATGGCCAGAATTGATTATGCTGTAAGC; and SSD449-02, CCAGTTTCAATGGTTTTGAAATAGCCC.

Microarray analyses.

Corning slides were microarrayed with 6,345 cDNA and genomic targets as previously described (19). Inserts from 5,655 cDNAs were generously provided by the Japanese EST Project (27, 38). A list of genes is available at http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/loomis-cgi/microarray/cbfA_array.html. All genes in this study were sequence verified. Probes were prepared from total RNAs collected at 2-h intervals during wild-type and mutant development, as well as from time-averaged reference RNA. Superscript II DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) was used to incorporate either Cy5- or Cy3-conjugated dCTP (Amersham, St. Louis, Mo.) into DNA. Labeled probes from the time points and the time-averaged RNA were mixed and hybridized at 42°C to microarrays for 6 to 12 h before being analyzed with a Genepix 4000B scanner (Axon Instruments, Foster City, Calif.). The total Cy3 signal was normalized to the total Cy5 signal after background subtraction to allow independent slides to be compared. The Cy3/Cy5 ratios for individual genes were then calculated at each time point for subsequent analyses. The expression patterns of mutant cells depleted in CbfA were compared to those of strain AX4, which are indistinguishable from those of strain AX2 (39).

RESULTS

CbfA-depleted cells are unable to aggregate.

CbfA was initially identified and purified by its specific binding to the C module of the retrotransposon TRE5-A (16). Using the highly specific monoclonal antibody 7F3 directed against the carboxy-terminal domain of CbfA (44), we showed that the CbfA protein level in AX2 cells is not sensitive to growth conditions (axenic culture or growth on bacteria) and stays constant throughout development. Using this same antibody, we found that the level of CbfA protein in cbfAam cells was <5% of that in wild-type cells during growth or following the initiation of development (reference 44 and data not shown).

We examined the effect of CbfA depletion in cbfAam cells on the multicellular development of D. discoideum cells. When cbfAam cells grew on lawns of bacteria, they formed very few, if any, fruiting bodies, reflecting poor aggregation of the mutant cells, leading to multicellular structures generated by only a few of the starving cells (44). When mutant cells were plated on phosphate-buffered agar at 1.6 × 106/cm2, the cbfAam cells did not show any sign of aggregation for at least 36 h and only very few, mostly crippled, fruiting bodies were observed after 72 h (data not shown). We could recover a few spores from these plates, and they gave rise to populations of mutant cells when spread on bacterial plates. cbfAam cells showed the aggregation defect at all cell densities tested (5 × 104 to 9 × 106 cells/cm2).

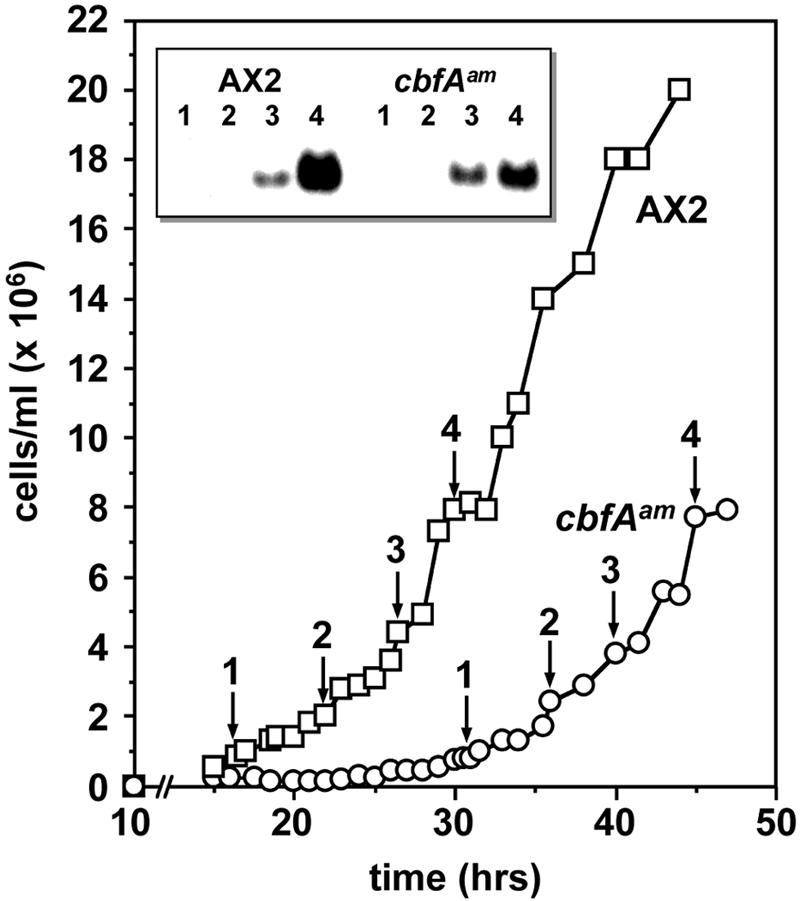

The failure of cbfAam cells to aggregate might be the consequence of their inability to sense their own density and food status. Therefore, we determined the cell density-dependent induction of discoidin expression as a measure of the prestarvation response (8, 9). Cells were grown in shaken cultures in the presence of bacteria and collected at various titers for Northern analyses of accumulation of discoidin I mRNA (Fig. 1). The cbfAam cells showed a pronounced lag in growth on bacteria as a consequence of impaired phagocytosis (44). Nevertheless, cbfAam cells showed almost normal, cell density-dependent expression of discoidin mRNA (Fig. 1) and protein (not shown), indicating that the prestarvation response of cbfAam cells is not affected by CbfA deficiency. These results were confirmed with axenically growing cbfAam cells, in which discoidin mRNA levels increased to 106 cells/ml and showed the characteristic repression at cell densities of >3 × 106 cells/ml also observed with AX2 cells (43) (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Cell density-dependent expression of discoidin I. AX2 and cbfAam cells were grown in shaken cultures in association with bacteria. At time points 1 to 4, indicated by the arrows, D. discoideum cells were collected, washed, and analyzed for discoidin I mRNA expression. The indicated samples 1 to 4 corresponded to cell densities of 1.0 × 106, 2.0 × 106, 4.4 × 106, and 7.9 × 106/ml for AX2 and 1.0 × 106, 2.4 × 106, 3.8 × 106, and 7.7 × 106/ml for strain JH.D. Total RNA was prepared from the cell samples and analyzed on a Northern blot with a discoidin Iγ-specific probe (inset).

cbfAam cells fail to activate cAMP pulse-induced genes in early development.

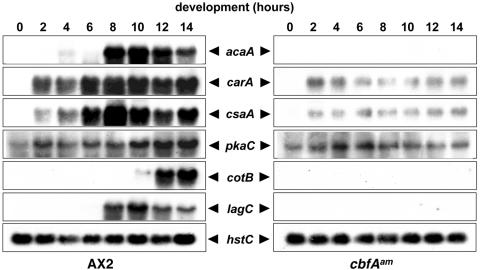

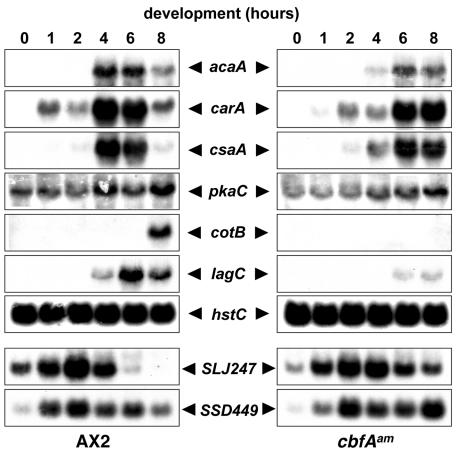

Although cbfAam cells reacted to prestarvation conditions, they did not acquire aggregation competence and thus stayed as a monolayer. The ability of a cell population to respond to and relay cAMP signals can be analyzed at the transcription level by measuring the induction of cAMP pulse-induced genes during aggregation. AX2 and cbfAam cells were spread on phosphate buffer-supported filters, and total RNA prepared from samples was collected over 14 h. Northern blots were hybridized with DNA probes specific for the cAMP pulse-induced genes carA, acaA, csaA, and pkaC (Fig. 2). Expression of the acaA gene was completely absent in cbfAam cells. The genes carA and csaA were induced to very low levels 2 h after starvation of the mutant cells. On Western blots, cbfAam cells did not express any detectable CsaA protein by 11 h after starvation on filters (data not shown). The mRNA encoding the catalytic subunit of PKA (pkaC) was fairly well expressed in growing and developing cbfAam cells, although the typical cAMP pulse-induced increase in pkaC expression seen at 8 h was not observed in the mutant cells (Fig. 2). We also tested for the expression of the postaggregative, cell-type-specific genes cotB and lagC. Both markers were well expressed in AX2 cells 8 to 14 h after starvation but were absent in the cbfAam cells under these conditions (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Expression of developmentally regulated genes in the cbfAam mutant JH.D developed on solid support. AX2 and cbfAam cells of strain JH.D were washed free of medium and spread on black filters at 5 × 107 per filter. Cell samples were collected every 2 h. RNA was extracted from the samples, and 40 μg of total RNA was loaded in each slot. The origins and preparation of 32P-labeled probes are described in Materials and Methods.

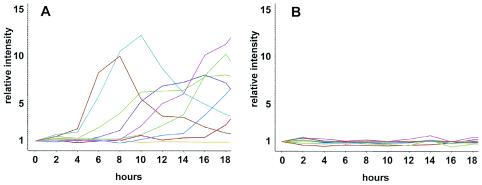

The Northern blot data suggested that the gene regulatory networks that establish and maintain cAMP relay may not be active in cbfAam cells. We used genomewide DNA microarrays carrying 6,345 targets (19) to characterize the expression kinetics of developmentally regulated genes in cbfAam cells. We focused on the expression patterns of 118 genes that can be grouped into clusters according to their successive induction at different stages of multicellular development (19) (Fig. 3A). When cbfAam cells were developed on filters, they did not show significant induction of any of the developmentally regulated gene clusters (Fig. 3B). Close inspection of the individual expression profiles of the early developmental genes tested on Northern blots revealed that expression of carA was induced only ∼3-fold in cbfAam cells (compared to 38-fold in wild-type cells) and then stayed constant throughout development at only ∼5% of the wild-type level (not shown). In wild-type cells, csaA expression increased eightfold 8 h after starvation but was not significantly induced in cbfAam cells. The gene acaA was not expressed at all in cbfAam cells. The only gene from the set of developmentally regulated genes that was expressed in a manner similar to that in the wild type was pdiA, the phosphodiesterase inhibitor that is repressed by cAMP pulses.

FIG. 3.

Microarray analysis of developmentally regulated genes in AX4 and cbfAam mutant JH.D developed on solid support. Samples were collected every 2 h for 18 h and analyzed on chips carrying 6,345 targets. Expression profiles of 118 developmentally regulated genes were extracted and clustered into 9 groups. Each cluster contains ∼10 genes and is color coded. A) wild-type AX4. B) cbfAam mutant JH.D.

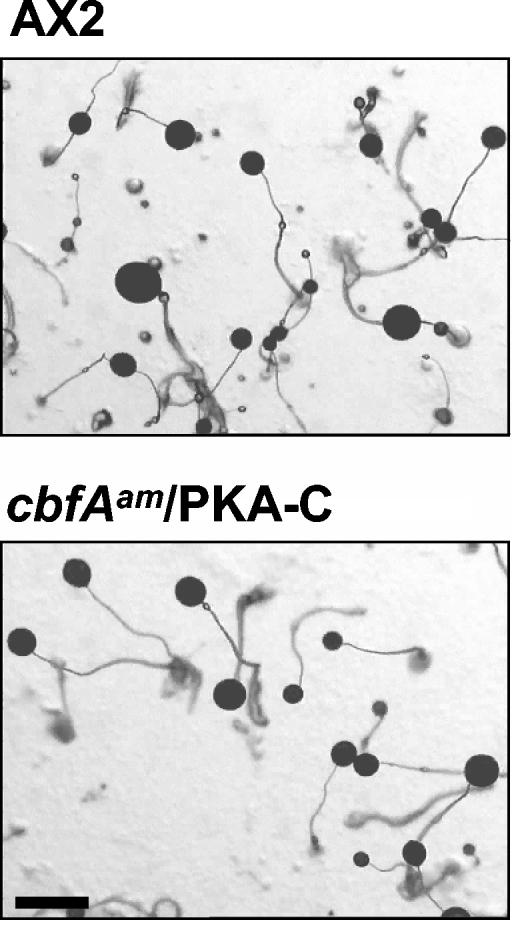

Developmental rescue of cbfAam cells.

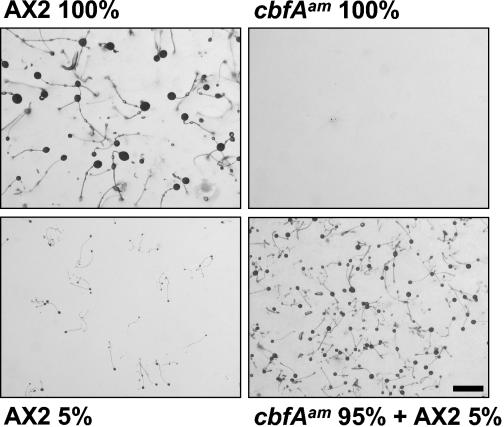

The aggregation defect of cbfAam cells most likely results from their inability to synthesize cAMP at a high rate as a consequence of failing to express acaA. However, we speculated that they might be able to respond to cells that are making cAMP. We mixed a small number of AX2 cells with cbfAam cells and found that the cbfAam cells developed significantly better in the presence of wild-type cells (Fig. 4). Spores isolated from the fruiting bodies were plated clonally on bacterial lawns, and most gave rise to clones with the cbfAam phenotype, thus demonstrating that the cbfAam cells had participated in forming the observed fruiting bodies (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Development of the cbfAam mutant in synergy with wild-type cells. Axenically cultured D. discoideum cells were washed and plated on phosphate-buffered agar. The 100% value corresponds to 108 plated cells per 9-cm-diameter petri dish. The pictures were taken 60 h after the cells were plated. Scale bar: 1 mm.

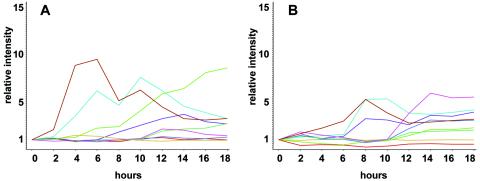

To determine if cbfAam cells developed in response to extracellular cAMP signals provided by the wild-type cells, we incubated AX2 and mutant cells in buffer and gave them artificial cAMP pulses at 6-min intervals for 4 h, starting 2 h after they were washed, and a final boost of 300 μM cAMP after 6 h. RNA was collected at 2-h intervals and analyzed on microarrays. Unlike cbfAam cells developed on filters, those developed in suspension and given cAMP pulses expressed the early genes, including acaA (Fig. 5). Accumulation of many of these early gene products was delayed ∼4 h and was somewhat attenuated compared to that of wild-type cells (Fig. 5). Thus, CbfA appears to play a role in early gene expression but can be partially bypassed if the cells are given exogenous cAMP pulses.

FIG. 5.

Microarray analysis of developmentally regulated genes in AX4 and cbfAam mutant JH.D developed in shaken culture with cAMP pulses. Samples were collected every 2 h for 18 h and analyzed on chips carrying 6,345 targets. Expression profiles of 118 developmentally regulated genes were extracted and clustered into 9 groups. Each cluster contains ∼10 genes and is color coded. A) wild-type AX4. B) cbfAam mutant JH.D.

The expression of some critical cAMP pulse-induced genes was analyzed on Northern blots to verify the microarray data. In the wild-type AX2 cells, the genes carA, acaA, and csaA were strongly induced by exogenous cAMP pulses and reached maximum expression 4 to 6 h after the beginning of starvation (Fig. 6). These genes were also induced in the mutant cells, albeit more slowly (Fig. 6). Expression of pkaC was almost normal in the cbfAam cells under these conditions. Thus, the time course of gene expression seen on Northern blots confirmed the DNA microarray data for these genes.

FIG. 6.

Northern analysis of developmentally regulated genes in the cbfAam mutant JH.D in shaken culture treated with cAMP. Axenically grown AX2 and cbfAam cells were harvested at 3.0 × 106/ml, washed free of medium, and suspended at 2 × 107/ml in phosphate buffer. The cells were shaken at 150 rpm at 22°C. Beginning 2 h after the cells were washed, cAMP pulses were applied every 6 min at a 30 nM final concentration, followed by a final boost of 300 μM cAMP after 6 h. RNA was extracted from cell samples, and 40 μg of total RNA was loaded in each slot. The origins and preparation of 32P-labeled probes are described in Materials and Methods.

In the DNA microarray experiments, we noticed two genes that were induced in cbfAam cells but not in AX4 cells after the onset of starvation. The gene SLJ247, which encodes CF50, a subunit of counting factor (5), was induced ∼6-fold (SLJ247), whereas expression of SSD449, an orphan gene, was induced ∼2-fold (data not shown). We analyzed the expression profiles of these two genes on Northern blots of cAMP-pulsed cells to see if they were in fact overexpressed in cbfAam cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 6). It turned out that both genes were in fact underexpressed in growing cbfAam cells compared to AX2 and were strongly induced soon after the beginning of starvation, thus giving an apparently stronger induction in the mutant than in the wild type. Both genes reached about the same expression levels in both wild-type and cbfAam cells by 2 h after starvation (Fig. 6). Notably, cAMP-induced repression of SLJ247 was delayed in the mutant strain. Apparently, underexpression of the gene encoding CF50 in growing cells is unlikely to contribute to the phenotype of cbfAam cells, since cf50 null cells form giant streams and fruiting bodies (5). Nevertheless, the fact that SSD449 and SLJ247 were induced in a cAMP-independent manner within the first 2 h following the removal of nutrients, well before the cells were treated with cAMP pulse, clearly indicates that cbfAam cells are able to sense starvation.

We also tested two postaggregation genes, lagC and cotB, for expression in cbfAam cells after cAMP pulsing. As shown in Fig. 6, cotB expression was absent under the experimental conditions used and lagC expression was only slightly induced and barely detectable.

When cAMP-treated cbfAam cells were plated after 8 h on phosphate-buffered agar plates to allow multicellular development, they were able to complete development significantly faster and more efficiently than mutant cells that had not been exposed to exogenous cAMP (data not shown). However, the developmental timing of cbfAam cells was still aberrant, since fruiting bodies were not formed until 31 h after plating, 6 h later than the formation of wild-type fruiting bodies. Moreover, there were fewer fruiting bodies due to inefficient entry of mutant cells into aggregates (data not shown).

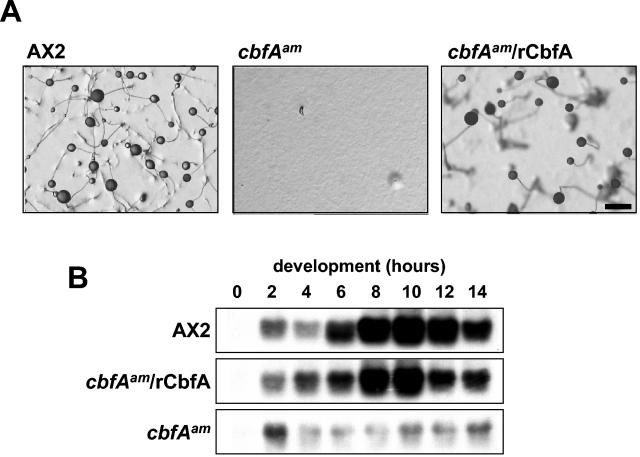

The developmental phenotype of cbfAam is complemented by recombinant CbfA.

To formally prove that the observed developmental defects of cbfAam cells were exclusively due to CbfA deficiency, we expressed a nearly full-length cbfA cDNA in the mutant cells under the control of the strong, constitutively active actin15 promoter. Using the CbfA-specific antibody 7F3, we found several cbfAam transformants that accumulated substantial levels of rCbfA (data not shown). These clones all developed normally and gave rise to normal-size fruiting bodies (Fig. 7A). Moreover, expression of early developmental genes, such as csaA, was returned to normal by expression of recombinant CbfA (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Complementation of the cbfAam phenotype by expression of recombinant CbfA. (A) D. discoideum cells were plated for multicellular development on phosphate-buffered agar plates. cbfAam cells were transformed with plasmid pDXA-rCbfA (cbfAam/rCbfA). Control AX2 and mutant cells were transformed with the empty vector pDXA-3H. The pictures were taken 40 h after the cells were plated. Scale bar: 1 mm. (B) Transformants were spread on black filters and allowed to aggregate as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Cell samples were collected every 2 h. RNA was extracted from the samples, and 40 μg of total RNA was loaded in each slot. Blotted RNAs were hybridized to a radiolabeled csaA probe.

Constitutive expression of PKA-C restores development of cbfAam cells.

The aggregation defect of the cbfAam mutant resembled in several respects the phenotype of acaA mutant cells. Wang and Kuspa (41) have shown that acaA mutant cells can aggregate when they overexpress pkaC, the gene encoding the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (41). To determine whether the development of cbfAam mutant cells can be restored by expression of pkaC, we transformed cbfAam cells with plasmids that allowed the expression of the pkaC cDNA either under the control of the authentic pkaC promoter or under the constitutively active actin6 promoter. Expression of PKA-C from both plasmids reproducibly overcame the aberrant development of cbfAam cells (shown in Fig. 8 for act6/pkaC), suggesting that accumulation of constitutive PKA-C can bypass the consequences of the lack of ACA caused by depletion of CbfA.

FIG. 8.

Complementation of the cbfAam phenotype by expression of recombinant PKA-C. cbfAam cells were transformed with plasmid p332 (12), so that expression of pkaC was under the control of the actin6 promoter (cbfAam/PKA-C cells). The cells were plated on phosphate-buffered agar plates. The pictures were taken 40 h after the cells were plated. Scale bar: 1 mm.

DISCUSSION

CbfA is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein that is essential for correct expression of acaA and other genes required to aggregate and develop following starvation and deposition of Dictyostelium cells on a moist support. CbfA contains protein motifs that likely act in DNA binding and transactivation of gene expression. The zinc fingers of CbfA may contribute to DNA binding and/or stabilization of the CbfA structure. The carboxy-terminal domain of CbfA contains an AT hook that is required for binding to the C module of retrotransposon TRE5-A in vitro (18) and that may also mediate binding to AT-rich binding sites in CbfA target gene promoters. The amino-terminal one-third of CbfA contains a jumonji domain that is essential for the regulation of early developmental genes (unpublished data). Hence, we speculate that CbfA is a transcription regulator that binds to AT-rich target sites in the D. discoideum genome and regulates the transcription of CbfA-dependent genes.

CbfA seems to be particularly important for the expression of the aggregation-specific adenylyl cyclase ACA. At present, we cannot resolve whether CbfA regulates the acaA gene directly or indirectly. CbfA recognizes two unusual binding sites in the C module of the retrotransposon TRE5-A. These consist of ∼24-bp oligoadenine sequences surrounded by nonconserved nucleotides. There are similar oligoadenine runs in the 500 bp preceding the acaA gene where CbfA might bind. However, given the generally high A+T content of the D. discoideum genome, it can be tested experimentally only if CbfA binds to the acaA promoter in vivo. In the absence of acaA gene expression, the cells cannot generate the extracellular pulses of cAMP that are necessary for chemotactic aggregation and stimulation of adjacent cells. As a result, CbfA-depleted cells fail to aggregate or to accumulate normal levels of early developmental mRNAs. However, if CbfA-depleted cells are developed in mixtures with wild-type cells or are given artificial pulses of cAMP while suspended in buffer, they can express acaA and other early developmental genes and develop into fairly normal fruiting bodies. However, both gene expression and fruiting body formation were delayed in cbfAam cells under these conditions, indicating that the role of CbfA cannot be completely bypassed by artificial cAMP pulses.

CbfA does not appear to be necessary for the prestarvation response, since CbfA-depleted cells express discoidin I in a manner determined by the cell density, as in wild-type cells. In wild-type cells, PSF induces the serine-threonine protein kinase YakA, which arrests growth and releases a translation block on pkaC mRNA (35, 36). Our data suggest that the YakA pathway functions normally in cbfAam cells, since yakA mutant cells show enhanced growth rates (whereas cbfAam cells grow slowly), and cAMP-pulsed yakA mutant cells express neither carA nor acaA (both of which are induced in cAMP-pulsed cbfAam cells) (Fig. 6). CbfA probably acts downstream of the YakA pathway and, either directly or indirectly, controls transcription of acaA and other early genes. When the cells are able to generate and respond to cAMP pulses, a CbfA-independent transcriptional pathway can take over.

CbfA does not appear to be necessary for cells to sense starvation, since expression of some very early genes increases immediately after mutant cells are washed free of nutrients. The major defects of cbfAam cells can be attributed to the lack of ACA, and like those of acaA null mutant cells, they can be bypassed by the constitutive PKA activity that results from overexpression of the catalytic subunit encoded by pkaC. It appears that all of the early internal signaling by cAMP is mediated by PKA. When cbfAam cells are treated with pulses of cAMP, the MAP kinase ERK2 is transiently activated and inhibits the internal phosphodiesterase so that cAMP generated by the other adenylyl cyclase ACR can accumulate (19). This stimulates PKA activity, which induces acaA and other early developmental genes, allowing the cbfAam cells to escape their trap.

A Myb-related transcription regulator (Myb2) that is also required for induction of acaA (28) has been described. Like cbfAam cells, those lacking mybB fail to aggregate but can be rescued by artificial pulses of cAMP. It is possible that in the absence of high levels of PKA activity, both CbfA and Myb2 are necessary to induce their target genes. Another gene, amiB, is known to be necessary for aggregation but can be bypassed by cAMP pulsing or ectopic expression of Myb2 (22). It appears to act upstream of CbfA and Myb2, since amiB null mutant cells fail to repress the vegetative gene cprD when starved, suggesting that they cannot sense starvation (22). The AmiB protein contains a domain that is significantly related to MAP kinase phosphatases and may be involved in the regulation of YakA, which acts upstream of PKA.

Although pulsing with cAMP partially bypassed the block to developmental gene expression in cbfAam cells, expression of these genes was generally reduced and delayed by 2 to 3 h (Fig. 5 and 6). Since cbfAam cells developed quite efficiently when mixed with wild-type cells, it may be that wild-type cells provided a secreted factor missing in the cbfAam mutant in addition to cAMP. This factor is unlikely to be CMF, since we found that cmfA is normally expressed in cbfAam cells (data not presented). However, we cannot presently exclude the possibility that a component of the CMF-controlled signaling pathways is dependent on CbfA, so that the cbfAam cells are unable to respond properly to CMF.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to C. Utner and D. Fuller for expert technical assistance. We thank B. Wetterauer, G. Gerisch, and C. Reymond for gifts of plasmids and antibodies.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to T.D. and T. W. (WI 1142/2-1 and WI 1142/2-2) and grants from the NIH (GM60447 and GM62350) to W.F.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anjard, C., S. Pinaud, R. R. Kay, and C. D. Reymond. 1992. Overexpression of DdPK2 protein kinase causes rapid development and affects the intracellular cAMP pathway of Dictyostelium discoideum. Development 115:785-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubry, L., and R. Firtel. 1999. Integration of signaling networks that regulate Dictyostelium differentiation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15:469-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brazill, D. T., D. F. Lindsey, J. D. Bishop, and R. H. Gomer. 1998. Cell density sensing mediated by a G protein-coupled receptor activating phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 273:8161-8168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brazill, D. T., R. Gundersen, and R. H. Gomer. 1997. A cell-density sensing factor regulates the lifetime of a chemoattractant-induced Gα-GTP conformation. FEBS Lett. 404:100-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brock, D. A., K. Ehrenman, R. Ammann, Y. Tang, and R. H. Gomer. 2003. Two components of a secreted cell number-counting factor bind to cells and have opposing effects on cAMP signal transduction in Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 278:52262-52272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bukenberger, M., J. Horn, T. Dingermann, R. P. Dottin, and T. Winckler. 1997. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding the nucleosome core histone H3 from Dictyostelium discoideum by genetic screening in yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1352:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke, M., and R. H. Gomer. 1995. PSF and CMF, autocrine factors that regulate gene expression during growth and early development of Dictyostelium. Experientia 51:1124-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke, M., S. C. Kayman, and K. Riley. 1987. Density-dependent induction of discoidin-I synthesis in exponentially growing cells of Dictyostelium discoideum. Differentiation 34:79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke, M., J. Yang, and S. Kayman. 1988. Analysis of the prestarvation response in growing cells of Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Genet. 9:315-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clissold, P. M., and C. P. Ponting. 2001. JmjC: cupin metalloenzyme-like domains in jumonji, hairless and phospholipase A2β. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:7-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig, N. L., R. Craigie, M. Gellert, and A. M. Lambowitz. 2002. Mobile DNA II. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Dammann, H., F. Traincard, C. Anjard, M. X. P. van Bemmelen, C. Reymond, and M. Veron. 1998. Functional analysis of the catalytic subunit of Dictyostelium PKA in vivo. Mech. Dev. 72:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faure, M., J. Franke, A. L. Hall, G. J. Podgorski, and R. H. Kessin. 1990. The cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase gene of Dictyostelium discoideum contains 3 promoters specific for growth, aggregation, and late development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:1921-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Firtel, R. A., and A. L. Chapman. 1990. Role for cAMP-dependent protein kinase-A in early Dictyostelium development. Genes Dev. 4:18-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franke, J., M. Faure, L. Wu, A. L. Hall, G. J. Podgorski, and R. H. Kessin. 1991. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase of Dictyostelium discoideum and its glycoprotein inhibitor—structure and expression of their genes. Dev. Genet. 12:104-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geier, A., J. Horn, T. Dingermann, and T. Winckler. 1996. A nuclear protein factor binds specifically to the 3′-regulatory module of the long-interspersed-nuclear-element-like Dictyostelium repetitive element. Eur. J. Biochem. 241:70-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomer, R. H. 1999. Cell density sensing in a eukaryote. ASM News 65:23-29. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horn, J., A. Dietz-Schmidt, I. Zündorf, J. Garin, T. Dingermann, and T. Winckler. 1999. A Dictyostelium protein binds to distinct oligo(dA) · oligo(dT) DNA sequences in the C-module of the retrotransposable element DRE. Eur. J. Biochem. 265:441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iranfar, N., D. Fuller, and W. F. Loomis. 2003. Genome-wide expression analyses of gene regulation during early development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Eukaryot. Cell 2:664-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iranfar, N., D. Fuller, R. Sasik, T. Hwa, M. Laub, and W. F. Loomis. 2001. Expression patterns of cell-type-specific genes in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2590-2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain, R., I. S. Yuen, C. R. Taphouse, and R. H. Gomer. 1992. A density-sensing factor controls development in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 6:390-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kon, T., H. Adachi, and K. Sutoh. 2000. amiB, a novel gene required for the growth/differentiation transition in Dictyostelium. Genes Cells 5:43-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loomis, W. F. 1996. Genetic networks that regulate development in Dictyostelium cells. Microbiol. Rev. 60:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda, M., H. Sakamoto, N. Iranfar, D. Fuller, T. Maruo, S. Ogihara, T. Morio, H. Urushihara, Y. Tanaka, and W. F. Loomis. 2003. Changing patterns of gene expression in Dictyostelium prestalk cell subtypes recognized by in situ hybridization with genes from microarray analyses. Eukaryot. Cell 2:627-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann, S. K. O., J. M. Brown, C. Briscoe, C. Parent, G. Pitt, P. N. Devreotes, and R. A. Firtel. 1997. Role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in controlling aggregation and postaggregative development in Dictyostelium. Dev. Biol. 183:208-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manstein, D. J., H. P. Schuster, P. Morandini, and D. M. Hunt. 1995. Cloning vectors for the production of proteins in Dictyostelium discoideum. Gene 162:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morio, T., H. Urushihara, T. Saito, Y. Ugawa, H. Mizuno, M. Yoshida, R. Yoshino, B. N. Mitra, M. Pi, T. Sato, K. Takemoto, H. Yasukawa, J. Williams, M. Maeda, I. Takeuchi, H. Ochiai, and Y. Tanaka. 1998. The Dictyostelium developmental cDNA project: generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags from the first-finger stage of development. DNA Res. 5:335-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otsuka, H., and P. J. M. van Haastert. 1998. A novel Myb homolog initiates Dictyostelium development by induction of adenylyl cyclase expression. Genes Dev. 12:1738-1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parent, C. A., and P. N. Devreotes. 1996. Molecular genetics of signal transduction in Dictyostelium. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:411-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitt, G. S., N. Milona, J. Borleis, K. C. Lin, R. R. Reed, and P. N. Devreotes. 1992. Structurally distinct and stage-specific adenylyl cyclase genes play different roles in Dictyostelium development. Cell 69:305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Primpke, G., V. Iassonidou, W. Nellen, and B. Wetterauer. 2000. Role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase during growth and early development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Biol. 221:101-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rathi, A., and M. Clarke. 1992. Expression of early developmental genes in Dictyostelium discoideum is initiated during exponential growth by an autocrine-dependent mechanism. Mech. Dev. 36:173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulkes, C., and P. Schaap. 1995. cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity is essential for preaggregative gene expression in Dictyostelium. FEBS Lett. 368:381-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaulsky, G., D. Fuller, and W. F. Loomis. 1998. A cAMP-phosphodiesterase controls PKA-dependent differentiation. Development 125:691-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souza, G. M., A. M. da Silva, and A. Kuspa. 1999. Starvation promotes Dictyostelium development by relieving PufA inhibition of PKA translation through the YakA kinase pathway. Development 126:3263-3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Souza, G. M., S. Lu, and A. Kuspa. 1998. YakA, a protein kinase required for the transition from growth to development in Dictyostelium. Development 125:2291-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sussman, M. 1987. Cultivation and synchronous morphogenesis of Dictyostelium under controlled experimental conditions. Methods Cell Biol. 28:9-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urushihara, H., T. Morio, T. Saito, Y. Kohara, E. Koriki, H. Ochiai, M. Maeda, J. G. Williams, I. Takeuchi, and Y. Tanaka. 2004. Analyses of cDNAs from growth and slug stages of Dictyostelium discoideum. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1647-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.VanDriessche, N., C. Shaw, M. Katoh, T. Morio, R. Sucgang, M. Ibarra, H. Kuwayama, T. Saito, H. Urushihara, M. Maeda, I. Takeuchi, H. Ochiai, W. Eaton, J. Tollett, J. Halter, A. Kuspa, Y. Tanaka, and G. Shaulsky. 2002. A transcriptional profile of multicellular development in Dictyostelium discoideum. Development 129:1543-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veron, M., R. Mutzel, M.-L. Lacombe, M.-N. Simon, and V. Wallet. 1988. cAMP-dependent protein kinase from Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Genet. 9:247-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, B., and A. Kuspa. 1997. Dictyostelium development in the absence of cAMP. Science 277:251-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wetterauer, B., G. Jacobsen, P. Morandini, and H. MacWilliams. 1993. Mutants of Dictyostelium discoideum with defects in the regulation of discoidin I expression. Dev. Biol. 159:184-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wetterauer, B. W., K. Salger, C. Carballo-Metzner, and H. K. MacWilliams. 1995. Cell-density-dependent repression of discoidin in Dictyostelium discoideum. Differentiation 59:289-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winckler, T., C. Trautwein, C. Tschepke, C. Neuhäuser, I. Zündorf, P. Beck, G. Vogel, and T. Dingermann. 2001. Gene function analysis by amber stop codon suppression: CMBF is a nuclear protein that supports growth and development of Dictyostelium amoebae. J. Mol. Biol. 305:703-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winckler, T., T. Dingermann, and G. Glöckner. 2002. Dictyostelium mobile elements: strategies to amplify in a compact genome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:2097-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]