Abstract

A decline in breastfeeding rates in Samoa has been reported over the last century. To assess the length of time women breastfeed, their knowledge of both the advantages of and recommendations for breastfeeding, and the factors that influence their decisions to continue or discontinue breastfeeding, a questionnaire was distributed at Tupua Tamasese Meaole Hospital. One hundred and twenty-one eligible participants were included aged 18–50 years (mean age 28.2). Ninety percent of participants initiated breastfeeding, and the majority (78%) of babies were exclusively breastfed for at least the recommended 6 months. Many mothers introduced complementary (solid) foods later than World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nation's International Children's Fund (UNICEF) recommendations of 6 months. Awareness of the advantages of breastfeeding was mixed. The most widely known advantage was “the development of an emotional bond between mother and baby” (67%). Other advantages were less widely known. Only a small minority were aware that breastfeeding reduces risk of maternal diabetes and aids weight loss post partum. Doctors and healthcare workers were listed as the top factors encouraging breastfeeding. Participants' comments revealed a generally positive attitude towards breastfeeding, a very encouraging finding. Participants identified that the number of breastfeeding breaks available at work and the length of their maternity leave were factors discouraging breastfeeding. Future studies are necessary to determine if problems identified in this study are applicable on a national level. These could be important to determine measures to improve breastfeeding practices in Samoa.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Samoa, Advantages, Infant nutrition, Perceptions

Introduction

Breastfeeding is the healthiest way for babies to feed. Evidence shows numerous benefits: it provides the optimal nutrients, growth factors and antibodies for the baby; aids maternal weight loss; helps to develop the emotional bond between mother and baby; acts as natural birth control and protects against maternal cancers.1 In developing countries where there is an increased risk of infections associated with bottle feeding, breastfeeding is the most hygienic method of infant feeding. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends initiation of breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth, exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and continued breastfeeding with initiation of solid foods.2 Long-term benefits include a reduced obesity risk for baby and a reduced risk of developing diabetes for both mother and baby. Obesity, defined as a Body Mass Index (BMI) >32kg/m2 for Polynesians, is a major problem in the independent nation of Samoa. A study published in 2014 showed 64.6% of females and 41.2% males in Samoa were obese. 3 This compares with 36% prevalence of obesity (defined as BMI >30kg/m2 in this population) in adult males and females in the United States.4 Furthermore the prevalence of diabetes mellitus is very high, with 23% of Samoans diagnosed with the condition and potentially others going undiagnosed.5 By encouraging optimal breastfeeding practices, this disease burden could be reduced.

Traditionally, nearly all babies in Samoa were breastfed. In 1951 the average age of weaning was 20 months.6 However, there has been a notable decline in breastfeeding rates in the latter half of the 20th century alongside the introduction of western diets, progressive urbanization, and migration of families to urban areas with more work available for women. In 2009, the United Nation's International Children's Fund (UNICEF) reported only 51.3% of women were exclusively breastfeeding up to 6 months.7

The Government of Samoa and UNICEF report suggests working commitments are a major barrier to breastfeeding.8 Traditionally, women would return to their parents' family for support while breastfeeding; this practice is often not possible for working mothers today. Women are legally entitled to a minimum of 4 weeks paid maternity leave, which does not enable mothers to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months.9 Employers are legally obliged to provide mothers with opportunities to breastfeed or express breast milk at work. However, there are practical difficulties to this. For example, with Samoa's hot climate, having an appropriate place for milk storage may not be possible in all work places. Samoa bureau of statistics shows that 2.6%–25.6% of women aged 15–49 years were employed; meaning employment cannot be the sole reason for decline in breastfeeding rates as at least 75% of women are not employed.10 The UNICEF report also highlights the availability of formula milk in Samoan shops as a potential influence on the cultural shift away from breastfeeding.8

A qualitative study among Maori women by Glover, et al, identified five influences to the decision of infant-feeding: the breakdown in the breastfeeding norm within their family; early interruptions or difficulties establishing breastfeeding; negative or insufficient support for breastfeeding; lack of knowledge about breastfeeding; and returning to work.11 A similar study in American Samoa highlighted convenience of formula milk, perceptions of insufficient milk, and pain as barriers to breastfeeding.12 These factors may be transferable to mothers in independent Samoa.

This study aims to identify factors that influence Samoan women's decision and ability to breastfeed. Further aims include: to determine whether Samoan women intended to breastfeed; to assess the awareness among Samoan mothers of the recommended time to exclusively breastfeed and the advantages of breastfeeding, and finally to determine whether employment status has an influence on length of time mothers breastfeed. This information could enable the Ministry of Health in Samoa to identify methods to further improve support available for mothers.

Methods

Ethics statement: Ethical approval was gained from the University of Birmingham's Ethical Review committee and Ministry of Health Research Committee Samoa and Tupa Tamasese Meaole (TTM) Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to completion of the questionnaire.

This cross-sectional prevalence study used a quantitative questionnaire (appendix 2) distributed at TTM Hospital, Apia, the national hospital of Samoa. The 12 questions used a tick-box format, including information about participants' demographics, length of time participants exclusively breastfed, knowledge of breastfeeding recommendations, and knowledge of advantages of breastfeeding. This questionnaire was created by the researchers using knowledge gained through previous research. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention breastfeeding study was used to develop questions and a qualitative study among Maori women, particularly those questions based around factors encouraging and discouraging women to breastfeed.13,11 The questionnaire also included a qualitative aspect using a comments section to allow exploration of cultural and other influences. Knowledge of advantages of breastfeeding and WHO breastfeeding recommendations were also assessed, as research shows knowledge and education is a determinant of breastfeeding practices.14,15 After data was entered into a database, questionnaires were destroyed and each response given a numerical value.

Eligible participants were females aged 18–50 years, with a child >6 months of age (mothers with a child above this age are more likely to have experienced the factors discussed in the questionnaire). Participants were recruited in the antenatal clinic waiting area. Women attending the clinic (as patients and their friends or family present) were asked if they had previously had a child. Other participants were recruited in the pediatric clinic waiting area. No incentives were offered for participation. Exclusion criteria were non-Samoan citizens and people who cannot speak either English or Samoan.

The questionnaire was translated from English into Samoan by two medical students attending the University of Samoa, fluent in both English and Samoan. It was distributed in clinic waiting rooms in both languages. A healthcare professional was able to read the consent form (appendix 1) and questionnaire to illiterate patients. If there were queries regarding the questionnaire, the principal investigator and a health care professional were available to discuss these. Convenience sampling was used in order to prevent interference with clinic or ward activities. Data collection took place over 2 weeks during May 2015.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using Microsoft Excel. To test whether significant differences existed in the length of exclusive breastfeeding and knowledge of breastfeeding the Student's t-test was used. To calculate whether a significant difference existed between the percentage of employed and unemployed participants who reported breastfeeding, a Chi-square test was applied with Yates' correction.

Results

Demographics

One hundred and twenty-six women responded to the questionnaire. Five of these were excluded; 2 because the participants had not yet had a child, 2 because the participants had not answered more than 1 question, and 1 because the participant was a non-Samoan citizen. This left 121 participants. The percentage of participants who were employed (35%) and have a college level of education or higher (96%) was significantly greater than the general population of Samoa (25% and 30% respectively).16 Participants' babies were born between 1986 and 2014. The majority of participants intended to breastfeed (97%), compared to those who said they did not intend to breastfeed (n=2, 3%). Table 1 shows participants'demographics.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Participants (%) | |

| N | 121 |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean | 28.2 |

| Range | 18–50 |

| Missing/Unknown | 9 |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 40 (35%) |

| Unemployed | 73 (65%) |

| Missing/Unknown | 8 |

| Location | |

| Urban | 45 (39%) |

| Rural | 70 (61%) |

| Missing/Unknown | 6 |

| Education | |

| Primary School | 2 (2%) |

| Secondary School | 2 (2%) |

| College | 73 (64%) |

| University | 37 (32%) |

| Missing Unknown | 7 |

| Intention to Breastfeed | |

| Planned to breastfeed | 113 (97%) |

| Did not plan to breastfeed | 3 (3%) |

| Missing/Unknown | 5 |

Percentages exclude unknown/missing

Length of Exclusive Breastfeeding

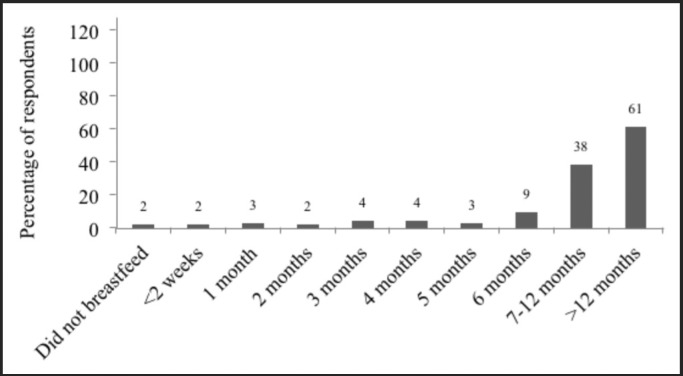

Out of the 121 participants, 117 responded to the question regarding length of exclusive breastfeeding. Seven participants gave 2 responses, and 2 participants gave 3 responses as they are multiparous. (Figure 1). This gave N=128 for number of responses. The majority of participants achieved at least 6 months exclusive breastfeeding 108 (84%; P<.0001, Student's t-test). Despite this, only 9 (7%) babies were weaned at 6 months. Ninety-nine women (77%; P<.0001, Student's t-test) reported exclusive breastfeeding beyond 6 months.

Figure 1.

Category which Participants Selected as the Length of Time They Exclusively Breastfed

Knowledge of Breastfeeding

Participants' reporting of extended exclusive breastfeeding is reflected in the participants' knowledge of the recommended breastfeeding times (Table 2). Eight respondents (7%) were correct in selecting 6 months as the WHO recommended length of time to exclusively breastfeed, while 75 (67%; P<.0001, Student's t-test) gave a value greater than 6 months.2 Twenty-five (22%) respondents selected “don't know.”

Table 2.

Length of Time of Exclusive Breastfeeding

| Participants perceiving this to be the recommended length of time of exclusive breastfeeding (%) | |

| N | 121 |

| Don't know | 25 (22%) |

| No breastfeeding | 1 (1%) |

| <2 weeks | 0 |

| 1 month | 0 |

| 2 months | 0 |

| 3 months | 1 (1%) |

| 4 months | 0 |

| 5 months | 2 (2%) |

| 6 months | 8 (7%) |

| 7–12 months | 9 (8%) |

| >12 months | 66 (59%) |

| Unknown/Missing | 9 |

Percentages exclude unknown/missing

Participants were presented with a list of facts and asked to identify which they believed to be an advantage of breast feeding (multiple options including “don't know” could be selected) (Table 3). The 2 most popular statements were: “develops an emotional bond between mother and baby” (84, 72%) and “reduces risk of long term health problems for baby” (67, 58%). The other advantages listed were known to less than half of respondents (Figure 2). Only 2 participants were aware of all the listed advantages. Very few participants were aware that breastfeeding reduces risk of diabetes (10, 9%) or helps the mother lose weight (6, 5%).

Table 3.

Advantages of Breastfeeding

| Participants aware of that advantage (%) | |

| N | 121 |

| Develops an emotional bond between mother and baby | 84 (72%) |

| Reduces risk of long term health problems for baby | 67 (58%) |

| Reduces baby's risk of infection | 50 (43%) |

| Reduces risk of breast cancer for mother | 36 (31%) |

| Natural birth control | 21 (18%) |

| Reduces baby's risk of cot death | 16 (14%) |

| Reduces risk of diabetes for mother | 10 (9%) |

| Helps mother with weight loss | 6 (5%) |

| Don't know | 2 (2%) |

| Unknown/Missing | 5 |

Participants could select more than one option hence percentages do not add up to 100. Percentages exclude unknown/missing.

Factors Affecting Breastfeeding

Eighty-nine (77%) participants stated that they were encouraged by a doctor to breastfeed and 48 (41%) by another healthcare worker (multiple categories could be selected) (Table 4). Family support was shown to be important as “encouragement from their partner/husband” (35, 30%) and “other family” (37, 33%) were highly selected options. Other factors were selected by fewer women. This question gave participants the option to add further comments. Many of these comments showed that the participants see breastfeeding as being very important. Such responses as “to make baby healthy,” “to stop baby becoming sick,” and “to show your baby your love as a mother, it is the right thing to breastfeed” highlight this. One participant mentioned that the money saving aspect of breastfeeding factored in her decision. The factors most frequently identified as making breastfeeding difficult were job related: “limited breaks to breastfeed at work” (23, 20%), and “limited maternity leave” (21, 18%). Table 5 reports other factors identified as discouraging breastfeeding. The comments for this question further highlight the participants' views on the importance of breastfeeding. Employment related comments included “You should take care of your baby wisely, the health of your baby is more important than your work.” Some participants mentioned that they found breastfeeding and work difficult, eg, “it is hard to breastfeed while you are working also” and “Less time for breastfeeding at times of work.” However, others said they had no trouble with breastfeeding. Despite work factors being the most reported discouraging factor for participants breastfeeding, we found no significant difference (P>.05) between employed and unemployed women in the likelihood that they would breastfeed (exclusively and following the introduction of solid foods).

Table 4.

Factors Encouraging Breastfeeding

| Participants who were encouraged to breastfeed by this factor (%) | |

| N | 121 |

| Doctor | 89 (77%) |

| Healthcare worker | 48 (41%) |

| Other Family | 37 (32%) |

| Partner/Husband | 35 (30%) |

| Traditional birthing assistant | 20 (17%) |

| Support group | 12 (10%) |

| Media advertisement | 10 (9%) |

| Traditions | 3 (3%) |

| Leaflets | 1 (1%) |

| Was not encouraged to breastfeed | 26 (22%) |

| Unknown/Missing | 5 |

Participants could select more than one option hence percentages do not add up to 100. Percentages exclude unknown/missing.

Table 5.

Factors Discouraging Breastfeeding

| Participants who were discouraged to breastfeed by this factor (%) | |

| N | 121 |

| Limited breastfeeding breaks at work | 23 (20%) |

| Limited maternity leave | 21 (18%) |

| Lack of support at home | 19 (16%) |

| Tobacco use | 18 (16%) |

| Difficulty initiating breastfeeding | 13 (11%) |

| Health problems/illness | 12 (10%) |

| Pain/discomfort | 12 (10%) |

| Experiences of family and friends | 9 (8%) |

| Lack of support from healthcare workers | 8 (7%) |

| Fatigue | 7 (6%) |

| Formula milk advertisement | 7 (6%) |

| Medications | 6 (5%) |

| Perceptions of breastfeeding in public | 5 (4%) |

| Difficulty storing breast milk | 5 (4%) |

| Fear of transmitting infection | 5 (4%) |

| Fear of not producing enough milk | 4 (3%) |

| Unknown/Missing | 5 |

Participants could select more than one option hence percentages do not add up to 100. Percentages exclude unknown/missing.

Discussion

This study explored the influences and beliefs surrounding breastfeeding practices among Samoan women. The results show that the majority of participants planned to (and did) breastfeed, with most reporting exclusive breastfeeding for >12 month”. In fact, more than half of participants believed that breastfeeding for >12 months is the recommended length of time to exclusively breastfeed for, while nearly one quarter of participants said they did not know. This statistic differs from the Samoa Demographic and Health Survey 2014 which suggests that 28.1% of women exclusively breastfeed beyond 6 months.16 This difference could partly be subject to recall bias and also confusion with the definition of ‘exclusive breastfeeding’. Despite this difference, both this study and the Demographic and Health Survey suggest a proportion of women exclusively breastfed beyond 6 months. Delayed introduction of solid foods can increase risks of obesity, type 1 diabetes, iron deficiency anaemia, and lead to poor sleep outcomes.17–19

Knowledge of advantages varied widely among participants, however only 2 women were aware that all factors listed were advantages. Only a minority were aware that breastfeeding reduces risk of diabetes for the mother and helps with weight loss. With diabetes and obesity being major health issues in Samoa, increasing awareness of advantages of breastfeeding could be beneficial.16

Doctors and healthcare workers were the highest selected factors that encouraged breastfeeding. This could be due to bias as participants were selected at the national hospital, therefore targeting potentially more health-conscious citizens who are more likely to have contact with health care professionals. Limited maternity leave and limited breastfeeding breaks at work were the most prevalent discouraging factors. If these problems are true on a national level, these could be overcome by legislating an increase in paid maternity leave from the current 4 weeks to WHO recommendations of 4 months.20 The Nutrition Center, Ministry of Health in Samoa already produce advice leaflets' for employers and employees, aiming to tackle these issues.

Some participants reported being discouraged from breastfeeding because of tobacco use. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends breastfeeding as the optimal source of nutrition for the baby despite presence of nicotine in breastmilk.16 Encouragement of smoking cessation for breastfeeding mothers should be combined with emphasis on continued breastfeeding, particularly as independent Samoa has a high proportion of smokers (33.6% of men and 13.3% of women) compared with the United States (17.2% of men and 14.2% of women) in 2013.21,22

Some participants reported difficulty initiating breastfeeding. Advice is provided at TTM Hospital to all new mothers regarding initiating of breastfeeding, however 36% of mothers do not receive postnatal care within 48 hours of delivery, and 33% do not receive any postnatal care.16 Encouraging women to attend a postnatal check, along with advertising peer support groups and community nurse services could be useful for mothers who are experiencing difficulties. Increasing awareness of these groups by making these leaflets readily available could be valuable to Samoan mothers. These groups could help women with other problems reported such as pain, discomfort and fatigue.

A small number of women mentioned they were concerned about transmitting infections via breast milk. Although the Government of Health estimated that HIV prevalence was <0.1% in 2014, mothers may have other infections such Hepatitis B (estimated 3% prevalence).23, 24 There is currently no evidence to suggest that babies are at increased risk of Hepatitis B from breastfeeding.24 Increased education surrounding this may be beneficial. This could be achieved by adding detail about Hepatitis B transmission to Ministry of Health breastfeeding leaflets. Women may also be worried about transmitting other infections, eg, viral illness to their babies. It would be useful to research which infections women are worried about transmitting further, to determine whether these problems encountered can be overcome through support groups and advice from midwives and leaflets.

It is encouraging that the majority of respondents state they achieved exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months. Recent health campaigns (billboard advertisements, leaflets, and information given by healthcare professionals on the labour ward) by the Ministry of Health in Samoa, may have contributed to this, however some women gave birth as long ago as 1986 which was before these health campaigns. The results may indicate that exclusive breastfeeding for longer than 6 months and a later introduction of food is prevalent among the research population.

It is promising to see evidence suggesting many women received encouragement to breastfeed from doctors and healthcare professionals. There were a high number of very positive comments stating participants' beliefs about the importance of breastfeeding. Only one woman stated that they received encouragement to breastfeed through the Ministry of Health's publication of leaflets. Although some woman gave birth before these leaflets were published in 2012, 68% gave birth to at least one of their children from 2012 onwards. This suggests that their distribution and availability could be improved. Leaflets containing breastfeeding advice and information are available for distribution in both the Ministry of Health building and in the waiting room of antenatal clinics at TTM hospital. However, the location of these in the clinic is not entirely obvious, particularly as many women wait outside the waiting room for their clinic appointments in the old hospital and very few patients will visit the Ministry of Health foyer. Distribution could be improved by all pregnant women being handed these leaflets routinely as part of their antenatal appointment. Despite recommendations, not all pregnant women attend this clinic. To further improve distribution, healthcare professionals travelling to rural clinics across the islands could take with them a selection of leaflets to give to any pregnant women or those with infants. Furthermore, it could be beneficial for the National Health Service to work with traditional healers, to aid the delivery of this information.

This study is limited by the relatively small sample size. This could be a topic for a larger scale study in the future. In order to avoid difficulties in comprehension, the questionnaire was translated into Samoan. However, a method to determine comprehensibility to lay people would have been via a pilot study. This was however not possible due to the time constraints.

The demographics of the women selected were different to the general population of Samoa. For example, our study shows that parity among the research population was 1.2; however, the average parity in Samoa is 4.6 (http://www.stats.gov.nz). Due to multiparous responses to the question regarding length of time of exclusive breastfeeding, the analysis of this question is limited and should be interpreted with caution. Seven women gave 2 responses and 2 women gave 3 responses. In addition, there were a greater proportion of participants receiving a college or university education. This could be due to the study being conducted in the national hospital in the city of Apia. It is possible that mothers who are educated may be more likely to live closer to the university, be more health aware and therefore attend hospital appointments. It is common for Samoan women to deliver at home and not attend the hospital for antenatal or postnatal checks. It is therefore possible that the group selected via convenience sampling is not a good representation of the whole population. Another limitation may be that, as many participants were aware that breastfeeding is the best thing for their baby (highlighted by many of their comments), they may have exaggerated the length of time they breastfed. Despite participants being assured that their answers would remain anonymous, reporter bias could still be present. Furthermore, some of the questions rely on accurate recall. The large age range of women and the spread of years which their children were born (1986–2014) introduces elements of recall bias, as well as cultural shifts with time, especially with rapid urbanization and modernization undergone by Samoa.

Although a qualitative approach may have provided in-depth understanding of women's views, due to limitations (including the language barrier, participants not having time for face to face interviews, and the influence of researcher bias) a quantitative structure was used. The study attempted to overcome this with the inclusion of a comments section. Ten participants in this study stated they had given birth prior to the adoption of a breastfeeding policy by the Ministry of Health in 1995.5 In order to assess the effectiveness of this policy, a future study with a larger cohort should aim to compare the effects of year of birth on the length of time women breastfed. A further improvement would be to utilize a stratified sampling technique including participants from smaller district hospitals and rural health clinics across both the islands Upolu and Savi'i to allow for a more representative population.

Despite limitations, this study is useful in identifying certain areas which need further research in order to improve breastfeeding practices in independent Samoa. Future studies should aim to identify a more representative population to study awareness of the advantages of breastfeeding and identify methods to improve education and awareness. Research should aim to clarify the disparity in rates of exclusive breastfeeding identified in this study in comparison to the Samoa Bureau of Statistics.16 The problems participants experienced related to breastfeeding in employment are vital to further investigate and identify methods to improve mothers working rights.

Acknowledgements

The Ministry of Health of Samoa. The Medical Students at the National University of Samoa who assisted our translation.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest. This work was supported by a grant from British Medical and Dental Students Association.

References

- 1.Leung AKC, Sauve RS. Breast is best for babies. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(7):1010–1019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation, author. Infant and Young Child Feeding. [17th December 2014]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs342/en.

- 3.Hawley NL, Minster RL, Weeks DE, et al. Prevalence of adiposity and associated cardiometabolic risk factors in the Samoan genome-wide association study. American Journal of Human Biology. 2014;26(4):491–501. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, author. Overweight and obesity statistics. [10th August 2016]. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/Pages/overweight-obesity-statistics.aspx.

- 5.World Health Organisation, author. Samoa: Non communicable diseases. [18th December 2014]. http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/wsm_en.pdf?ua=1.

- 6.Unicef, author. Samoa: Statistics. [17th December 2014]. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/samoa_statistics.html.

- 7.World Health Organisation, author. United Kingdom: Non communicable diseases. [18th December 2014]. http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/gbr_en.pdf?ua=1.

- 8.Government of Samoa and Unicef, author. Samoa: A Situation Analysis of Children, Women and Youth. [17th December 2014]. http://www.unicef.org/pacificislands/Samoa_sitan.pdf.

- 9.Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Labour, author. Labour and Employment Relations Act 2013. [19th December 2014]. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---ilo_aids/documents/legaldocument/wcms_201328.pdf.

- 10.Samoa Bureau of Statistics, author. Samoa Demographic and Health Survey 2014. [10th August 2016]. http://www.sbs.gov.ws/index.php/new-document-library?view=download&fileId=1648.

- 11.Glover M, Manaena-Biddle H, Waldon J. Influences that affect Maori women breastfeeding. Breastfeed Rev. 2007;15(2):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawley NL, Rosen RK, Strait EA. Mothers' attitudes and beliefs about infant feeding highlight barriers to exclusive breastfeeding in American Samoa. Women Birth. 2001;28(3):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. The Questionnaires. [10th August 2016]. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/ifps/questionnaires.htm.

- 14.Chezem J, Friesen C, Boettcher J. Breastfeeding knowledge, breastfeeding confidence, and infant feeding plans: effects on actual feeding practices. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32(1):40–47. doi: 10.1177/0884217502239799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellin PS, Poplawski DT, Gole A. Impact of a formal breastfeeding education program. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2011;36(2):82–88. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e318205589e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samoa Bureau of Statistics, author. Government of Samoa Demographic and Health Survey 2014. [5th August 2016]. http://www.sbs.gov.ws/index.php.

- 17.Kock L. Nutrition: Risk of T1DM increases with early and late weaning. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2013;9:504. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sultan AN, Zuberi RW. Late weaning: the most significant risk factor in the development of iron deficiency anaemia at 1–2 years of age. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2003;15(2):3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan JB, Lucas A, Fewtrell MS. Does weaning influence growth and health up to 18 months? Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:728–733. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.036137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organisation, author. Breastfeeding at work; lets make it work - what law makers can do. [5th August 2015]. http://who.int/mediacentre/events/meetings/2015/WHO_BreastfeedingWeek2015_EN.jpg?ua=1.

- 21.The Tobacco Atlas. Samoa. [5th August 2016]. http://www.tobaccoatlas.org/country-data/samoa/

- 22.The Tobacco Atlas. United States. [5th August 2016]. http://www.tobaccoatlas.org/country-data/united-states/

- 23.UNAIDS, author. Global AIDS response progress report 2015 - Government of Samoa. [11th August 2015]. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/WSM_narrative_report_2015.pdf.

- 24.World Health Organisation, author. Hepatitis B and breastfeeding. [11th August 2015]. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/pdfs/hepatitis_b_and_breastfeeding.pdf.