Abstract

We have determined the proportions of the prespore and prestalk regions in Dictyostelium discoideum slugs by in situ hybridization with a large number of prespore- and prestalk-specific genes. Microarrays were used to discover genes expressed in a cell type-specific manner. Fifty-four prespore-specific genes were verified by in situ hybridization, including 18 that had been previously shown to be cell type specific. The 36 new genes more than doubles the number of available prespore markers. At the slug stage, the prespore genes hybridized to cells uniformly in the posterior 80% of wild-type slugs but hybridized to the posterior 90% of slugs lacking the secreted alkylphenone differentiation-inducing factor 1 (DIF-1). There was a compensatory twofold decrease in prestalk cells in DIF-less slugs. Removal of prespore cells resulted in cell type conversion in both wild-type and DIF-less anterior fragments. Thus, DIF-1 appears to act in concert with other processes to establish cell type proportions.

Cell type divergence and subsequent tissue proportioning is critical to the development of all multicellular organisms. In metazoans the initial cell types are established in response to intrinsic and extrinsic signals, but final tissue proportions are regulated to a large extent by differential growth. Development in Dictyostelium spp. is initiated by depletion of the food source and proceeds in the absence of nuclear DNA replication (19). However, two major cell types, prespore and prestalk cells, diverge during aggregation of initially homogeneous populations into slug-like organisms containing up to 105 cells (5, 6, 9, 14). The proportions of these cell types are regulated in a size-invariant manner to give rise to the optimal ratio of spores and stalk cells in the final fruiting bodies. It has been proposed that DIF-1, a chlorinated alkylphenone produced by prespore cells and degraded by prestalk cells, controls cell type differentiation by inhibiting prespore differentiation and inducing prestalk differentiation (2, 4, 24, 10, 3, 12).

The last step in the biosynthesis of differentiation-inducing factor 1 (DIF-1) involves a methyltransferase. Mutant strains lacking this enzyme, DMT1, have been isolated and shown to accumulate no measurable DIF-1 (22). Nevertheless, these dmtA mutant cells differentiate into prestalk and prespore cells that sort out to the anterior and posterior of slugs, just as they do in wild-type slugs, and the mutant cells form fairly normal fruiting bodies complete with spores and stalk cells. However, a genetic marker for a subset of prestalk cells defined as being at the posterior of the prestalk region, the PST-O cells, was not expressed in DIF-less slugs, and there was an increase in the number of prespore cells (22). Expression of the marker construct, ecmO::gal, could be induced by codeveloping dmtA mutant cells with wild-type cells or adding exogenous DIF-1. These results led to the suggestion that, while not essential for all prestalk differentiations, DIF-1 is required for differentiation of PST-O cells (22).

A genome-wide microarray study subsequently uncovered a large number of prestalk-specific genes, and in situ hybridization showed that 30 of these were preferentially expressed in PST-O cells (14). While 18 of these PST-O genes were significantly reduced in slugs of the dmtA mutant strain, the remaining 12 genes were strongly expressed in PST-O cells. Thus, it appears that some aspects of PST-O differentiation are DIF independent. Our results indicate that analysis of only one gene is insufficient for understanding the in vivo function of DIF-1.

Previously, 79 cell type-specific genes that are preferentially expressed in one or another of the three prestalk subdomains of a slug (PST-A, PST-AB, and PST-O) based on their position were described (14). We can now add 54 prespore genes recognized by microarray expression studies and confirmed by in situ hybridizations. We used these cell type-specific genes for in situ hybridizations to compare wild-type and dmtA mutant slugs. In the absence of DIF-1 the prespore region at the posterior expanded from 80 to 90% of the length, with a compensatory shrinkage of the anterior prestalk region to 10% of the length of the slugs. While each prestalk subdomain was proportionally reduced, their order along the axis was retained, suggesting that their proportions are determined by factors other than DIF-1. Furthermore, we found that microsurgically isolated prestalk regions from dmtA mutant slugs were able to regulate within 6 h such that a prespore gene was expressed in the majority of the cells at the posterior, suggesting that a field-wide inhibitor of prespore differentiation other than DIF-1 emanates from the prespore domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microarray analysis.

The microarray analyses were performed as previously described (7, 14). Briefly, RNA was prepared from slugs of strain Ax4 following separation of dissociated cells on Percoll density gradients (8). Equal amounts of RNA prepared from prestalk cells or prespore cells were used to generate Cy3- or Cy5-labeled probes. Three independent determinations were carried out, and the ratios of prestalk to prespore mRNAs were averaged. Expression patterns for the prespore-specific genes were culled from the developmental time course data of Iranfar et al. (7). Values for each gene are available at http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/loomis-cgi/microarray/prespore.html.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as previously described (14). Our in situ studies were carried out with whole slugs or prestalk isolates of strain AX2 and dmtA mutant strain HM1030, which is defective in DIF-1 production (21). After fixation, samples from each stage were mixed and hybridized in a single tube or a dish. Digoxigenin- or fluorescein-labeled riboprobes were generated for the entire length of each cDNA clone for hybridization to either sense or antisense RNA.

For double staining, digoxigenin- and fluorescein-labeled riboprobes were used for hybridization at 42°C overnight. After rinsing and then blocking, samples were incubated with Alexa 488-labeled anti-fluorescein antibody (diluted 1/500) and rhodamine-labeled anti-digoxigenin antibody (diluted 1/500) (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) at 4°C overnight. After washing and blocking, signals were detected with an Olympus Epifluorescent microscope BX50.

Sequences of all cDNAs used in this study can be drawn from the Dicty-cDNA database (http://www.csm.biol.tsukuba.ac.jp/cDNAproject.html).

RESULTS

Microarray analyses and temporal expression patterns.

Microarrays were generated by using 5,655 cloned inserts from the Japanese cDNA Project (15, 23) together with 690 targets previously amplified from developmental genes (7, 14). The ratios of prestalk mRNAs to prespore mRNAs were determined after hybridization with Cy3- and Cy5-labeled probes. The results for each target can be found at http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/loomis-cgi/microarray/prespore.html. Using a combination of genome-wide surveys for genes that are preferentially expressed fourfold or more in prespore cells and in situ hybridization, we identified 54 prespore-specific genes (Table 1). Eighteen of these were known to be prespore specific from previous studies (8), while 36 were newly recognized to be prespore specific.

TABLE 1.

Prespore genes

| Accession no. | Clone name | Product and/or homology | Intensity on microarrays (prespore/ prestalk ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AU072889 | SSF323 | Prespore II protein | 32.3 |

| AU060672 | SLK851 | CotB | 19.2 |

| C93960 | SSC859 | AqpA | 18 |

| AU038678 | SSL337 | Unknown | 17.6 |

| AU060684 | SLB103 | Related to SP85 (le-12) | 15.3 |

| AU038352 | SSH606 | Related to glutathione S-transferase (2e-19) | 14.5 |

| AU033521 | SLB126 | CotC | 14.3 |

| C84233 | SSB358 | Related to glutathione S-transferase (8e-10) | 14.1 |

| AU061603 | SLE779 | Related to EcmB (6e-11) | 13.3 |

| AU074151 | SSJ638 | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | 12.3 |

| C93875 | SSL817 | Prespore specific protein 3B | 11.2 |

| AU060210 | SLA580 | Related to mouse Gpr97 (2e-04) | 10.9 |

| AU071513 | SSB695 | Related to stress response protein (9e-10) | 9.8 |

| AU060158 | SLA466 | Unknown | 9.7 |

| AU074346 | SSK438 | Related to discoidin II (7e-53) | 9.5 |

| AU037337 | SSB791 | Unknown | 9.4 |

| C93202 | SSM768 | Unknown | 9.1 |

| C94045 | SSG326 | Related to dipeptidyl aminopeptidase (3e-06) | 8.6 |

| AU062273 | SLI845 | Related to endopeptidase Clp (7e-27) | 8.6 |

| AU071293 | SSB171 | Unknown | 8.1 |

| AU039723 | SLG263 | EIF-4D | 8.1 |

| C92118 | SSD113 | Related to PAO1 protein (3e-40) | 7.3 |

| AU034007 | SLB722 | Related to glutamate decarboxylase (2e-68) | 6.9 |

| AU073964 | SSJ106 | Unknown | 6.9 |

| AU071553 | SSB780 | Related to CARG protein (3e-21) | 6.8 |

| AU073587 | SSH604 | WacA | 6.7 |

| AU073629 | SSH704 | Unknown | 6.3 |

| AU061992 | SLH115 | CotA | 6.2 |

| AU033901 | SLB586 | PspD (SP87) | 6 |

| AU060674 | SLK857 | Unknown | 5.8 |

| AU061772 | SLF822 | Related to alpha-mannosidase (4e-33) | 5.8 |

| C92150 | SSD150 | Unknown | 5.8 |

| AU060889 | SLC104 | ABC G6 | 5.7 |

| C84812 | SSF894 | Unknown | 5.5 |

| AU062282 | SLI892 | Related to AICAR transformylase (6e-42) | 5.5 |

| AU060827 | SLB616 | Related to SpiA (3e-05) | 5.4 |

| AU062238 | SLI623 | Related to peroxiredoxin 4 protein (8e-40) | 5.1 |

| C94332 | SSK846 | Cyclophilin | 5.1 |

| C94084 | SSG386 | Unknown | 5.1 |

| AU053006 | SLF503 | SP85 (PspB) | 5 |

| AU034063 | SLB871 | EF-1A | 5 |

| AU061750 | SLF677 | Unknown | 5 |

| AU034952 | SLE392 | Related to lipase (2e-32) | 5 |

| AU072303 | SSE143 | Unknown | 4.9 |

| AU073745 | SSI248 | Unknown | 4.8 |

| AU060363 | SLJ453 | Unknown | 4.8 |

| AU071509 | SSB684 | Unknown | 4.7 |

| AU060216 | SLA591 | Related to Dp87 (2e-27) | 4.5 |

| AU060153 | SLA449 | Related to heat shock protein hsp101 (4e-63) | 4.5 |

| C90848 | SSJ225 | Unknown | 4.4 |

| AU061109 | SLD233 | Related to SEC1 (2e-30) | 4.2 |

| C94273 | SSK726 | Unknown | 4.2 |

| C92915 | SSF756 | Cbp9 | 4.1 |

| AU037446 | SSJ770 | PspA (D19) | 4 |

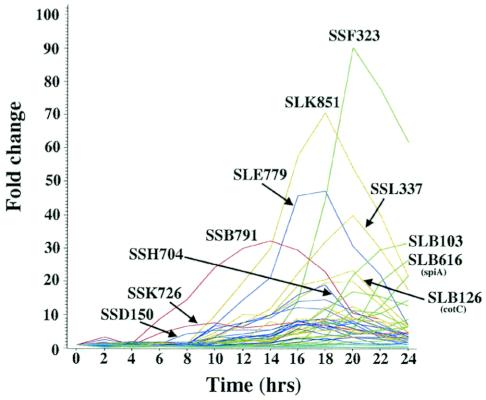

The temporal expression patterns of these prespore genes were determined by microarray analyses of samples collected throughout development on filters (7, 14). Most of these genes were first expressed between 8 and 12 h after the initiation of development, but three of them (SSD150, SSK726, and SSB791) started to be expressed at 4 h of development (Fig. 1). A few, such as SLB103 and SLB616 (spiA), were not expressed until after 16 h of development.

FIG. 1.

Expression patterns of prespore genes. RNAs prepared at 2-h intervals throughout development on filters were analyzed on microarrays. Values were normalized to 1 at the time of initiation of development, and the fold changes are presented for the 54 prespore genes analyzed in this study. Values are the averages of four independent determinations. Genes showing the greatest changes are indicated by name.

Expression patterns of prespore genes in migrating slugs.

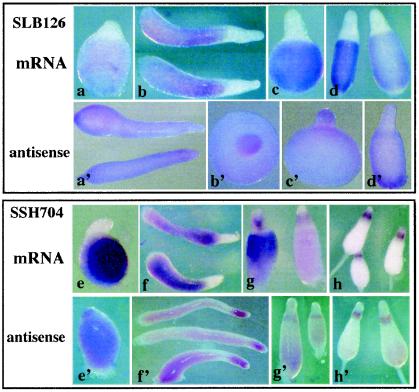

In situ hybridization revealed that almost all prespore genes were expressed throughout the posterior regions of tipped aggregates, slugs, Mexican hats, and early culminants with the same pattern as that seen for SLB126 (Fig. 2a to d). Probing with the sense strand for each of these genes showed only background staining (Fig. 2a′ to d′), except for SSH704 (Fig. 2 e to h′). Antisense RNA of this gene accumulated in the anterior regions of slugs, where it might play a role in limiting the accumulation of sense mRNA. Alternatively, it fortuitously cross-hybridized with the product of a prestalk-specific gene. Later in development, SSH704 mRNA decreased in the prespore cells and accumulated in cells at the back of the prestalk region, where upper cup cells are found (Fig. 2g and h). Because SSH704 antisense RNA also accumulated in these cells (Fig. 2 g′ and h′), it is not clear that it would be translated during culmination. In contrast to prestalk-specific genes, where we saw complex patterns of expression in different cell types throughout the course of development (14), the prespore genes showed a generally uniform distribution in the posterior 80%.

FIG. 2.

In situ hybridization with prespore genes. The pattern of staining of posterior cells by SLB126 (cotC) for mRNA (a to d) or antisense RNA (a′ to d′) is representative of almost all of the prespore genes. Patterns for each of the 54 prespore genes can be inspected at http://www.csm.biol.tsukuba.ac.jp/∼tools/bin/ISH/index.html. Only SSH707 and two other cDNAs derived from the same gene, which encodes a protein with no significant homologs, gave a significantly different pattern (e to h′). Up to the culmination stage its mRNA accumulated in posterior cells just like that of other prespore genes; however, its antisense RNA was seen in anterior cells (f′). During culmination, SSH704 mRNA disappeared from the prespore cells and both mRNA and antisense RNA accumulated in cells at the back of the prestalk domain.

Increase in the proportion of prespore cells in slugs lacking DIF.

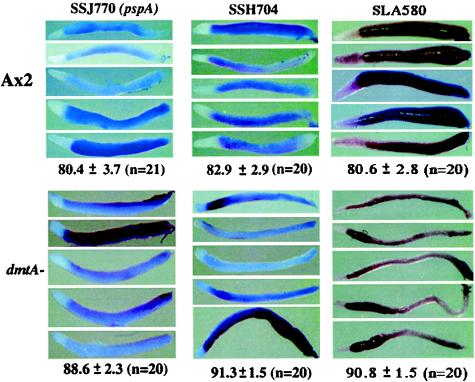

Because DIF-1 is known to repress certain prespore genes in cells dissociated from multicellular aggregates (5, 24), we determined the expression pattern of 18 prespore genes by in situ hybridization in the dmtA mutant strain that fails to synthesize measurable DIF (22). Comparison of the staining patterns of all of these genes showed an expansion of the expression region as shown in Fig. 3 for SSJ770, SSH704, and SLA580. By measuring the proportion of the length stained in more than 20 wild-type and 20 mutant slugs with each of seven prespore genes, we found that the prespore region made up about 80% of wild-type slugs and about 90% of dmtA mutant slugs (Table 2). It appears that DIF plays a significant role in regulating the proportion of prespore cells but that other processes repress prespore genes in the most anterior cells, confirming and extending the results of Thompson and Kay (22).

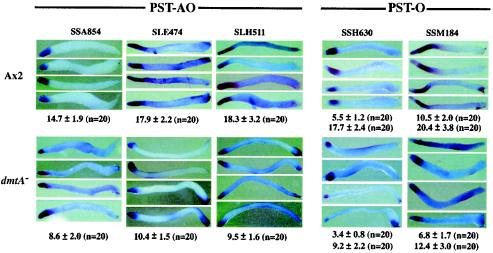

FIG. 3.

Prespore regions in slugs of wild-type and DIF-less slugs. Expression of three prespore genes was analyzed by in situ hybridization on more than 20 slugs prepared from wild-type Ax2 and dmtA mutant strains. Proportional lengths were measured, and the ratio and standard deviations were calculated for each gene by NIH image.

TABLE 2.

Expression ranges of cell type-specific genes in slugs

| Cell type | Clone | Gene expression (avg. ± SD, n = 20) for strain:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Ax2 | dmtA mutant | ||

| Prespore | SLA580 | 80.6 ± 2.8 | 90.8 ± 1.5 |

| SLE837 | 81.2 ± 2.0 | 90.8 ± 1.8 | |

| SLF822 | 80.1 ± 1.9 | 90.6 ± 1.6 | |

| SSB695 | 81.8 ± 2.6 | 91.0 ± 1.3 | |

| SSH704 | 82.9 ± 2.9 | 91.3 ± 1.5 | |

| SLH868 | 80.4 ± 2.3 | 91.9 ± 1.3 | |

| SSJ770 | 80.4 ± 3.7 | 88.6 ± 2.3 | |

| Prestalk PST-AO | SSL349 | 19.2 ± 1.8 | 9.5 ± 1.6 |

| SSJ314 | 18.7 ± 2.1 | 11.8 ± 1.3 | |

| SLH511 | 18.3 ± 3.2 | 9.5 ± 1.6 | |

| SLE474 | 17.9 ± 2.2 | 10.4 ± 1.5a | |

| SSA854 | 14.7 ± 1.9 | 8.6 ± 2.0 | |

| SSB337 | 14.4 ± 2.2 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | |

| Prestalk PST-A | SSK861 | 6.0 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 0.3 |

| SLF308 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 0.9b | |

| Prestalk PST-O | SSB559 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.8 |

| 21.4 ± 2.1 | 8.7 ± 0.9 | ||

| SSM184 | 10.5 ± 2.0 | 6.8 ± 1.7 | |

| 20.4 ± 3.8 | 12.4 ± 3.0 | ||

| SSH630 | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | |

| 17.7 ± 2.4 | 9.2 ± 2.2 | ||

| SSD764 | 4.2 ± 0.9 | No expression | |

| 15.6 ± 2.1 | No expression | ||

| SSL481 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | |

| 15.3 ± 1.6 | 8.3 ± 1.5 | ||

n = 19.

n = 18.

Decrease in the proportion of prestalk cells in slugs lacking DIF.

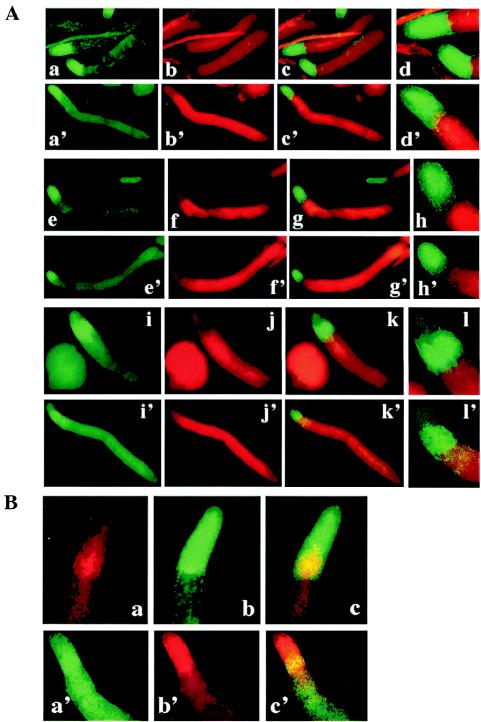

Expansion of the prespore domain in dmtA mutant slugs could come at the expense of prestalk cells, or the two cell types might be interdigitated where they abut. We used double labeling for in situ staining of wild-type and dmtA mutant slugs with a prespore gene (pspA) and three prestalk genes (SLE474 [ecmA], SSA854, and SSM184) (Fig. 4A). In each case there was a sharp demarcation between the differentially stained cells. SLE474 (ecmA) was expressed in the anterior 18% of wild-type cells (Fig. 4A, panels a to d) and in a smaller domain at the anterior of dmtA mutant slugs (Fig. 4A, panels a′ to d′). SSA854 was expressed in the anterior 15% of wild-type slugs (Fig. 4A, panels e to h) but not in the cells just ahead of the prespore domain, leaving a clear area where neither probe hybridized. In DIF-less slugs the stain was restricted to a smaller anterior region, but the clear area was still apparent (Fig. 4A, panels e′ to h′). SSM184 is only expressed in PST-O cells at the back of the prestalk region of wild-type slugs, leaving the PST-A cells unstained (Fig. 4A, panels i to l). In the DIF-less slugs, this gene also stained PST-O cells which were found closer to the front of the slug (Fig. 4A, panels i′ to l′). There appeared to be little, if any, overlap between cells expressing the prespore marker and those expressing any of the prestalk markers. This was especially clear in slugs stained with pspA and SSA854, where unmarked cells separated the stained cells (Fig. 4A, panels e to h).

FIG. 4.

Double-staining in situ hybridization. (A) Slugs formed from wild-type Ax2 and dmtA mutant strains were hybridized with prestalk probes to generate a green signal and were hybridized simultaneously with prespore probe SSJ770 (pspA) to generate a red signal. (a to d′) SLE474 (ecmA); (e to h′) SSA854; (i to l′) SSM184. (a to l) wild-type Ax2; (a′ to l′) dmtA mutant strain. (a, a′, e, e′, i, and i′) Prestalk gene expression revealed by the Alexa 488 signal. (b, b′, f, f′, j, j′) Expression of SSJ770 (pspA) revealed by the rhodamine signal. (c, c′, g, g′, k, k′) Merged pictures. (d, d′, h, h′, l, l′) Enlarged slug anteriors. The stained regions did not overlap and were separated by unstained cells in the case of SSA854. (B) Simultaneous analysis of spatial expression patterns of PST-AO and PST-O genes. Slugs formed from wild-type Ax2 (a to c) and dmtA mutant strain (a′ to c′). Expression of SSM184 (a PST-O gene) was detected with rhodamine (a), while expression of SLE474 (ecmA, a PST-AO gene) in Ax2 slugs was detected with Alexa 488 (b). (c) Merged picture of the images shown in panels a and b. In dmtA mutant slugs, SSM184 was detected with Alexa 488 (a′), while SLE474 was detected with rhodamine (b′). (c′) Merged picture of the images shown in panels a′ and b′. Regions with cells expressing both the PST-O and the PST-AO genes appear yellow in the merged pictures.

We double stained both wild-type and dmtA mutant slugs with a PST-AO marker, SLE474 (ecmA), and a PST-O marker, SSM184, to demonstrate overlap and maintenance of order of the cell types (Fig. 4B). Although the proportions of both the PST-A and PST-O regions were reduced in DIF-less slugs, the order was exactly reproduced.

To quantitate the change in proportions of prestalk cell types resulting from the lack of ability to synthesize DIF-1, we measured the relative lengths of regions stained with three PST-AO- and two PST-O-specific genes in 20 wild-type and 20 dmtA mutant slugs (Fig. 5). In each case the stained regions were reduced about twofold in the DIF-less slugs relative to the length of the region in wild-type slugs (Table 2). Staining of structures at later stages in development showed that these genes continued to be expressed in these prestalk domains through culmination of both wild-type and dmtA mutant strains. Likewise, PST-A specific genes (SLF308 and SSK861) stained the most anterior of slugs and the top of culminants, while PST-AB genes such as SSK348 and SLA128 stained cells in the anterior funnel of slugs and the stalks in both wild-type and dmtA mutant strains (data not shown). While the lack of DIF-1 reduced the proportion of PST-A and PST-O cells, it did not result in the mislocalization or absence of any of the prestalk cell types (Table 2).

FIG. 5.

Prestalk regions in wild-type and DIF-less slugs. Expression of three PST-O genes and two PST-O genes was analyzed by in situ hybridization of 20 slugs prepared from wild-type Ax2 and dmtA mutant strains. Proportional lengths were measured, and the ratio and standard deviations were calculated for each gene. The PST-O genes (SSH630 and SSM184) are not expressed in the most anterior cells. The anterior as well as the posterior borders were measured for these genes.

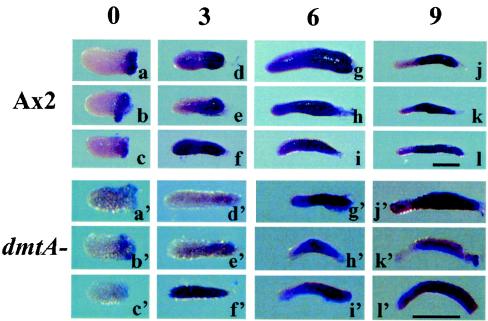

Regulation of cell types in isolated prestalk fragments.

Classical experiments have shown that cell type conversion occurs among prestalk cells when they are microsurgically separated from prespore domains (16). When culmination occurred in the anterior portions more than 6 h after excision, the resulting fruiting bodies approached normal proportions of stalk and spore-containing sori. To further define this process at the molecular level, we analyzed prespore gene expression by in situ hybridization to fragments isolated from the anteriors of migrating slugs (Fig. 6). The proportion of cells expressing the prespore gene pspA increased within 3 h following the isolation of prestalk fragments of wild-type slugs and continued to increase, such that after 9 h the proportions were not significantly different from those seen in unmolested slugs of similar size. Most of the stained cells were found at the posterior of the fragments, where prespore cells are to be expected.

FIG. 6.

Cell type conversion in isolated prestalk fragments. The anterior 20% of wild-type Ax2 slugs and the anterior 10% of dmtA mutant slugs were dissected and incubated in isolation. At the indicated times (in hours) after removal of the posterior tissue, the prespore marker SSJ770 (pspA) was used for in situ hybridization. Cell type conversion was apparent in the back of the fragments within a few hours.

When the same experiment was carried out with anterior portions from dmtA mutant slugs, we found that the number of cells expressing the prespore-specific gene also increased within 3 h following excision of the prestalk region (Fig. 6). By 9 h following excision, about 80% of the prestalk cells had regulated such that they expressed the prespore gene. These newly differentiated cells were found at the back of the small slugs.

DISCUSSION

Microarray-based genome-wide screens for cell type-specific genes in Dictyostelium spp. have now recognized 104 prestalk genes and 54 prespore genes that have each been validated by in situ hybridization (14 and this work). These genes provide a wealth of information concerning the differences and similarities between prespore and prestalk cells. Many of the prespore-specific genes encode components of the spore coats that are deposited during encapsulation (Table 1). Others encode homologs of diverse enzymes and stress response components. It is somewhat surprising that no proteins with DNA binding motifs that could function as transcription factors were encountered, but they might be hidden among the unknown proteins. Three of the prespore-specific genes encoding proteins with no significant homology to known proteins or conserved motifs are first expressed at 4 h of development and continue to be expressed for the following 12 h (Fig. 1). It is not yet clear if these genes are initially expressed in many cells and then preferentially repressed in prestalk cells, but by the tipped mound stage their mRNAs are found only in the prespore cells at the base. Another 30 genes, including the major spore coat genes, start to be expressed at 8 h of development and continue to be expressed for the following 12 h. Fifteen prespore genes are induced between 10 and 12 h of development, including the gene encoding UDP-glucose epimerase that is responsible for generating the precursor of the mucopolysaccharide found in the sorus. Only two genes, spiA and SLB103, were found to be strongly expressed after 16 h of development. spiA encodes a late spore coat protein and has been shown to be expressed in a wave that passes down the sorus near the end of culmination (17). SLB103 encodes a protein carrying two copies of a 5-amino-acid repeat found in the spore coat protein SP85 (PspB) that may also play a role in spore physiology. Both of these late genes start to be expressed at the top of sori and, only later, throughout the sori (data not shown). It is clear that prespore genes are subject to several distinct temporal controls and are not all expressed coordinately at the same stage of development.

Many years ago it was shown that the proportion of spores and stalk cells was invariant in fruiting bodies of widely different sizes (1). The process which results in this surprising result appears to occur much earlier during the slug stage. In situ hybridization of slugs that varied more than 10-fold in size with the prespore marker cotC showed that the proportions of prespore cells was essentially the same in large and small slugs (13). A mechanism that could account for size invariance has been proposed in which prespore cells produce an inhibitor to which they themselves are insensitive but which blocks prestalk cells from differentiating into prespore cells (20). If the inhibitor is broken down or inactivated by prestalk cells, this mechanism can robustly establish a constant proportion of the cell types over a wide range in the total cell number. DIF-1 was initially a candidate for the role of such an inhibitor, but the phenotype of strains unable to synthesize DIF-1 due to disruption of the enzyme DMT, which catalyzes the last step in DIF-1 biosynthesis, appeared to rule it out, because they expressed some prestalk genes in the anterior of slugs and were able to make fairly normal stalks (22). These dmtA mutant cells were shown to accumulate less than 5% as much DIF-1 as wild-type cells, below the limit of detection, but it is possible that there is some residual DIF-1 which functions in prestalk differentiation. The fact that slugs of a dmtA mutant strain do not express a PST-O marker construct and have an increased number of prespore cells indicates that DIF-1 plays an essential role in differentiation of PST-O cells (22). We have confirmed that certain PST-O genes, such as SSD764 (Table 2), are not expressed in the absence of DIF-1. However, other genes expressed in cells just anterior to prespore cells (PST-O cells) are expressed normally in DIF-less slugs of the dmtA mutant strain (Fig. 4 and 5). By quantitating the proportion of PST-A, PST-O, and prespore regions in wild-type and dmtA mutant slugs, we found that DIF-1 plays a significant role is regulating the proportion of the cell types, because the prestalk domain in wild-type slugs is double that in dmtA mutant cells (Table 2). However, DIF-1 does not appear to be the only signal involved in proportioning the cell types, because the anterior 10% of dmtA mutant slugs still express prestalk genes and do not express prespore genes. Moreover, the order of the prestalk subtypes recognized by patterns of expression of different prestalk genes is not affected by the absence of DIF-1. By quantitating the expression domains of a large number of prestalk genes, we could recognize at least five classes on the basis of their posterior boundaries (Table 2 and unpublished data). Subdivision of cells of the prestalk domain into PST-A and PST-O cells was based solely on expression patterns seen with portions of the ecmA regulatory region (9) and may be an oversimplification. A DIF-independent mechanism appears to pattern the prestalk domain into a series of distinct regions that can be distinguished by their unique transcriptional profiles.

When culmination occurs in anterior fragments soon after they are separated from the cells at the back, long stalks are made that carry almost no spores; however, if the isolated anterior fragments migrate for more than 6 h before culminating, the resulting fruiting bodies carry a considerable number of spores (16). These results indicated that prestalk cells had to regulate to be able to undergo terminal differentiation into spores. We were able to directly observe regulation in isolated prestalk fragments by in situ hybridization to a prespore gene (pspA). Initially, very few cells carried this mRNA, but the number increased within the first 3 h following microsurgical isolation. By 9 h most of the cells in the posterior 80% of the newly made small slugs had expressed the prespore gene. Assuming there was little or no axial mixing of the cells, it is of interest that the first cells to regulate into prespore cells appeared at the posterior, suggesting that cell type determination in these cells is more labile than that in ones closer to the front. The model that can account for size-invariant proportioning can also account for regulation following perturbation of the cell type proportions (20). When prespore cells are excised, the source of the inhibitor of prespore differentiation is removed while breakdown of the inhibitor can proceed. As cells at the back of the isolated prestalk fragments regulate to become prespore cells they start to produce the inhibitor, which increases until a threshold is reached that precludes the regulation of further prestalk cells. The nature of the proposed inhibitor is not known, but it does not appear to be DIF-1, because regulation was also observed in dmtA mutant anterior fragments. However, like DIF-1, it appears to be produced by prespore cells, because regulation among prestalk cells occurs only after the prespore cells are removed.

A DIF-insensitive mutant was recently characterized and shown to carry a disruption of the dimA gene, which encodes a DNA binding protein of the bZIP family (21). This mutant strain exhibits all of the phenotypes of dmtA mutant null cells, except that it produces DIF-1 and is not responsive to the addition of DIF-1. DimA appears to be responsible for optimal expression of a prestalk gene marker (ecmA) and repression of a prespore gene marker (pspA) in PST-O cells which may partially account for the mutually exclusive patterns of gene expression in prespore and prestalk cells. However, we have shown that a considerable number of prestalk-specific genes are expressed in a DIF-independent manner, indicating that other processes are involved in the initial divergence of cell types (14, 18).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mariko Tomisako, K. Nishio, and M. Yokoyama for their technical assistance with in situ hybridization.

This study was supported by grants from Research for the Future of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS-RFTF96L00105) and grants in aid for scientific research in priority areas “Genome Biology” from MEXT of Japan (12206001) to M.M. and to Y.T. and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM62350) to W.F.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonner, J. T., and M. K. Slifkin. 1949. A study of the control of differentiation: the proportions of stalk and spore cells in the slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. Am. J. Bot. 36:727-734. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brookman, J. J., K. A. Jermyn, and R. R. Kay. 1987. Nature and distribution of the morphogen DIF in the Dictyostelium slug. Development 100:119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Early, A., T. Abe, and J. Williams. 1995. Evidence for positional differentiation of prestalk cells and for a morphogenetic gradient in Dictyostelium. Cell 83:91-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early, V. E., and J. G. Williams. 1988. A Dictyostelium prespore-specific gene is transcriptionally repressed by DIF in vitro. Development 103:519-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fosnaugh, K. L., and W. F. Loomis. 1993. Enhancer regions responsible for temporal and cell-type-specific expression of a spore coat gene in Dictyostelium. Dev. Biol. 157:38-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haberstroh, L., and R. A. Firtel. 1990. A spatial gradient of expression of a cAMP-regulated prespore cell type-specific gene in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 4:596-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iranfar, N., D. Fuller, and W. F. Loomis. 2003. Genome-wide expression analyses of gene regulation during early development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Euk. Cell 2:664-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iranfar, N., D. Fuller, R. Sasik, T. Hwa, M. Laub, and W. F. Loomis. 2001. Expression patterns of cell-type-specific genes in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12:2590-2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jermyn, K. A., K. T. Duffy, and J. G. Williams. 1989. A new anatomy of the prestalk zone in Dictyostelium. Nature 340:144-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kay, R. R. 1992. Cell differentiation and patterning in Dictyostelium. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 4:934-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kay, R. R., and K. A. Jermyn. 1983. A possible morphogen controlling differentiation in Dictyostelium. Nature 303:242-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kay, R. R., and C. R. L. Thompson. 2001. Cross-induction of cell types in Dictyostelium: evidence that DIF-1 is made by prespore cells. Development 128:4959-4966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loomis, W. F. 1996. Genetic networks that regulate development in Dictyostelium cells. Microbiol. Rev. 60:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda, M., H. Sakamoto, N. Iranfar, D. Fuller, T. Maruo, S. Ogihara, T. Morio, H. Urushihara, Y. Tanaka, and W. F. Loomis. 2003. Changing patterns of gene expression in Dictyostelium prestalk cell subtypes recognized by in situ hybridization with genes from microarray analyses. Euk. Cell 2:627-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morio, T., H. Urushihara, T. Saito, Y. Ugawa, H. Mizuno, M. Yoshida, R. Yoshino, B. N. Mitra, M. Pi, T. Sato, K. Takemoto, H. Yasukawa, J. Williams, M. Maeda, I. Takeuchi, H. Ochiai, and Y. Tanaka. 1998. The Dictyostelium developmental cDNA project: generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags from the first-finger stage of development. DNA Res. 5:335-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raper, K. B. 1940. Pseudoplasmodium formation and organization in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 56:241-282. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson, D. L., W. F. Loomis, and A. R. Kimmel. 1994. Progression of an inductive signal activates sporulation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Development 120:2891-2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaulsky, G., and W. F. Loomis. 1996. Initial cell type divergence in Dictyostelium is independent of DIF-1. Dev. Biol. 174:214-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaulsky, G., and W. F. Loomis. 1995. Mitochondrial DNA replication but no nuclear DNA replication during development of Dictyostelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5660-5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soderbom, F., and W. F. Loomis. 1998. Cell-cell signaling during Dictyostelium development. Trends Microbiol. 6:402-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson, C. R. L., Q. Fu, C. Buhay, R. R. Kay, and G. Shaulsky. 2004. A bZIP/bRLZ transcription factor required for DIF signaling in Dictyostelium. Development 131:513-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson, C. R. L., and R. R. Kay. 2000. The role of DIF-1 signaling in Dictyostelium development. Mol. Cell. 6:1509-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urushihara, H., T. Morio, T. Saito, Y. Kohara, E. Koriki, H. Ochiai, M. Maeda, J. G. Williams, I. Takeuchi, and Y. Tanaka. 2004. Analyses of cDNAs from growth and slug stages of Dictyostelium discoideum. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1647-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams, J. G., K. T. Duffy, D. P. Lane, S. J. McRobbie, A. J. Harwood, D. Traynor, R. R. Kay, and K. A. Jermyn. 1989. Origins of the prestalk-prespore pattern in Dictyostelium development. Cell 59:1157-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]