Abstract

Victimization and depressive distress symptoms represent serious and interconnected public health problems facing transgender communities. Avoidant coping is hypothesized to temporarily alleviate the stress of victimization, but has potential long-term mental and behavioral health costs, such as increasing the probability of depressive symptoms. A community sample of 412 transgender adults (M age = 32.7, SD = 12.8) completed a one-time survey capturing multiple forms of victimization (i.e., everyday discrimination, bullying, physical assault by family, verbal harassment by family, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence), avoidant coping, and past-week depressive symptomology. Structural equation modeling examined the mediating role of avoidant coping in the association between victimization and depressive symptomology. A latent victimization variable composed of six measures of victimization was positively associated with avoidant coping, which in turn was positively associated with depressive symptoms. Victimization was also positively associated with depressive symptomology both directly and indirectly through avoidant coping. Avoidant coping represents a potentially useful intervention target for clinicians aiming to reduce the mental health sequelae of victimization in this highly stigmatized and vulnerable population.

Keywords: victimization, discrimination, bullying, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, coping, depression, transgender

Transgender individuals have a gender identity or expression (binary or non-binary) that differs from their assigned birth sex (Reisner, Biello, et al., 2014). In the U.S., transgender individuals experience high levels of stigma-related victimization (Stotzer, 2009; White Hughto, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015). Stigma toward transgender people occurs across settings (e.g., home, school, work, healthcare) and can include multiple forms of victimization such as discrimination (e.g., denial of services or resources), verbal harassment (e.g. mis-gendering, name calling), or physical violence (e.g., hate crimes, sexual assault) (Lombardi, 2009; Mizock & Lewis, 2008; Mizock & Mueser, 2014; White Hughto, Murchison, Clark, Pachankis, & Reisner, 2016). Transgender individuals in the U.S. are particularly at risk for victimization relative to their cisgender peers. In a study of 295 transgender adults and their cisgender siblings, over 90% of transgender adults reported experiencing harassment or discrimination across settings, compared to 80% of their cisgender sisters and 63% of their cisgender brothers (Factor & Rothblum, 2008). Similarly, in a national report of sexual and gender minorities and HIV-infected survivors and victims of intimate partner violence (n=3,111), transgender individuals were 2.0 times as likely to face threats/intimidation, 1.8 times as likely to experience harassment, and 4.4 times as likely to face police violence than people who did not identify as transgender (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 2013). Victimization also begins at a young age for many transgender people (Grant et al., 2011; Reisner, Greytak, Parsons, & Ybarra, 2015). In an online study of 5,542 adolescents, ages 13 to 18 years old, transgender youth disproportionately experienced bullying compared to their non-transgender counterparts as 82.6% of transgender youth were bullied in the past 12 months compared to 57.5% of cisgender boys and 57.9% of cisgender girls (Reisner, Greytak, et al., 2015). Transgender individuals may also experience rejection by family, including verbal harassment and physical assault, as a national study of more than 6,000 transgender people found that (57%) of participants had experienced rejection by their parents or another family member due to their gender identity/expression and 19% had experienced family violence (Grant et al., 2011). Stigma-related victimization persists throughout the life-course for many transgender people and is associated with poor mental health (Stotzer, 2009; White Hughto et al., 2015).

Transgender individuals are disproportionately at risk for depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder. For example, across studies, the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms in transgender people varies from 35% to 62%, depending on measurement and timeframe (Budge, Adelson, & Howard, 2013; Clements-Nolle, Marx, Guzman, & Katz, 2001; Nemoto, Bodeker, & Iwamoto, 2011; Nuttbrock et al., 2010; Reisner et al., 2016; Reisner, Vetters, et al., 2015; Reisner, White, Mayer, & Mimiaga, 2014; Tebbe & Moradi, 2016), compared to an estimated 17% lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder in the US general population (Kessler et al., 2005). Depressive symptoms have been linked to multiple forms of victimization among transgender individuals, including bullying, childhood sexual abuse, and physical violence by strangers, intimate partners, and family members (Bockting, Miner, Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013; Nemoto et al., 2011; Nuttbrock et al., 2010; Stotzer, 2009; White Hughto et al., 2015). Gender minority stress theory (Hendricks & Testa, 2012) summarizes the psychosocial impact of multiple forms of discrimination on the health of transgender individuals. Derived from stress theories applied to other minority groups (e.g., SES, Dohrenwend, 2000; race, Williams, Yan, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997; and sexual minority status, Meyer, 2003b), gender minority stress theory posits that stigma-related victimization establishes stressful environments for transgender individuals, which then generates cognitive, affective, and behavioral stress processes that adversely impact health.

The manner in which an individual appraises and copes with victimization has been shown to play a significant role in determining whether or not a person experiences poor mental health in response to mistreatment (Folkman & Lazarus, 1986, 1988; Wagner, Myers, & McIninch, 1999; Wills, 1986). Under the minority stress model (Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Meyer, 2003b; Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008), coping strategies buffer against the effects of stress. Coping strategies can include the employment of both individual and group resources such as developing a positive sense of self-esteem around one’s minority group identity, garnering social support, and fighting oppression through collective activism (Ashmore, Deaux, & McLaughlin-Volpe, 2004; Meyer, 2003b; Meyer et al., 2008; Testa, Jimenez, & Rankin, 2014). Conversely, under the minority stress model, lack of access to coping resources in the form of social support or personal resiliencies is thought to exacerbate the psychological distress experienced as a result of victimization. Recognizing that personal coping strategies are not necessarily intrinsic to an individual, but may develop in response to stress (Bal, Van Oost, De Bourdeaudhuij, & Crombez, 2003; Herman-Stabl, Stemmler, & Petersen, 1995; Merwin, Rosenthal, & Coffey, 2009; Newman, Holden, & Delville, 2010), researchers extended the minority stress theory to conceptualize coping as a mediator in the relationship between minority stress and mental health (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009; Szymanski & Owens, 2008). Preliminary tests of these mediation models with sexual minority individuals show that both adaptive and maladaptive personal coping strategies can develop in response to stressors, in turn influencing mental health (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Szymanski & Owens, 2008).

Adaptive coping strategies include directly mitigating the distress-causing problem or regulating one’s emotional response to the problem (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Szymanski & Owens, 2008), while maladaptive strategies are those that allow individuals to not deal directly with the problem by avoiding the stressor (e.g., avoiding people, using substances, eating, sleeping) or wishing the problem would go away (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Szymanski & Owens, 2008). For individuals who have been victimized, the physical avoidance of people or places where one might experience violence or discrimination, or be reminded of previous victimization experiences, may function to prevent the physical and emotional consequences of victimization (Beevers & Meyer, 2004; Merwin et al., 2009). In this way, the development of behaviorally avoidant coping strategies may be adaptive. However, the more a person who has been victimized tries to avoid exposure to victimization or suppress distressing thoughts associated with the threat of victimization, the more powerful and persistent those thoughts may become (Abramowitz, Tolin, & Street, 2001; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Merwin et al., 2009). Consequently, an individual engaging in avoidant coping may feel hopeless regarding whether or not the psychological threat of past experiences will ever dissipate (Merwin et al., 2009) and possess low self-efficacy for preventing future experiences of victimization through less avoidant means. These avoidant coping strategies might ultimately result in poor mental health (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Kaysen et al., 2014; Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014; Szymanski & Owens, 2008; Thomas, Witherspoon, & Speight, 2008).

The mediating role of avoidant coping in the relationship between minority stress and poor mental health has been documented among diverse minority populations. In a series of studies of sexual minority women, Szymanski and colleagues found that internalized heterosexism (i.e., the process of internalizing the ideological system that serves to stigmatize and reject any non-heterosexual identity or way of being) was positively associated with psychological distress and that avoidant coping partially mediated the relationship between internalized heterosexism and psychological distress (Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014; Szymanski & Owens, 2008). Similarly, in a study of African American women, avoidant coping partially mediated the positive relationship between gendered racism and psychological distress (Thomas et al., 2008). Among transgender individuals, a mixed method study found that discrimination (e.g., employment or education discrimination) was positively associated with coping, however, the quantitative portion of the study did not differentiate between adaptive and maladaptive (i.e., avoidant coping) strategies and the mediating role of coping was not explored (Mizock & Mueser, 2014). The subsequent qualitative portion of the study revealed that transgender individuals utilized multiple forms of coping in response to experiences of transgender-related discrimination, including emotionally detaching or physically avoiding a stressor (Mizock & Mueser, 2014). In 2013, Budge and colleagues examined associations between both avoidant coping and facilitative (i.e., adaptive) coping, social support, and depressive symptoms among transgender adults and found that avoidant coping was positively associated with past-week depressive symptoms and mediated the relationship between social support and depressive symptoms. No relationship was found between facilitative coping and depressive symptoms (Budge et al., 2013). While research shows that avoidant coping is employed by transgender people in response to various minority stressors, and also positively associated with depressive symptoms, whether avoidant coping mediates the victimization-depressive symptoms relationship remains unexamined among transgender populations.

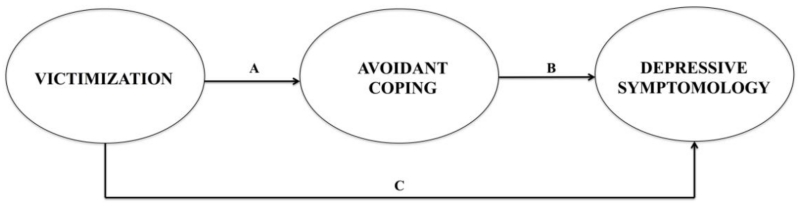

Although accumulating evidence shows that transgender people experience multiple forms of victimization, questions remain as to whether or not victimization is positively associated with depressive symptomology both directly and indirectly through avoidant coping among this population. Figure 1 displays the hypothesized associations in our adapted minority stress model of avoidant coping and depressive symptomology. Consistent with previous research (Bockting et al., 2013; Nemoto et al., 2011; Nuttbrock et al., 2010; Stotzer, 2009; Tebbe & Moradi, 2016; White Hughto et al., 2015), we propose that victimization – a minority stressor – will be positively associated with depressive symptomology. Also consistent with extant work (Grant et al., 2011), we propose that victimization will be positively associated with avoidant coping. Extending prior research conducted with non-transgender samples that linked minority stress to poor mental health by way of avoidant coping (Kaysen et al., 2014; Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014; Szymanski & Owens, 2008; Thomas et al., 2008), we hypothesize that avoidant coping will act as a mediator through which victimization is positively associated with depressive symptomology. We tested our hypothesis by examining the associations between a latent variable comprised of multiple forms of victimization (e.g., discrimination, bullying, physical and sexual violence), avoidant coping, and depressive symptomology and assessing whether avoidant coping mediates the relationship between victimization and depressive symptomology.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized meditational model of avoidant coping: Victimization is positively associated with avoidant coping strategies directly and indirectly through depressive symptomology.

Method

Participants and Procedures

A community sample of 452 transgender residents of Massachusetts, ages 18 to 75 years, completed an online survey between August and December 2013 that assessed victimization, coping, and health. A short and a long version of the survey were fielded. Only participants who completed the long survey (N = 412), which included questions on coping, were included in this analytic sample.

Since some transgender individuals may not identify as transgender, but fall under the transgender umbrella (e.g., non-binary, gender queer, gender fluid), we recruited individuals who self-identified as transgender and/or gender non-conforming in order to ensure that we enrolled both binary [i.e., male-to-female (MTF) and female-to-male (FTM)] and non-binary (e.g., gender queer, gender fluid) transgender individuals. Transgender status was assessed by asking participants to report their assigned sex at birth (female, male) and then their current gender identity (man, woman, female-to- male (FTM)/trans man, male-to-female (MTF)/trans woman, genderqueer, gender variant, gender nonconforming, other). The two items were cross-tabulated to categorize participants as being on the female-to-male (FTM) trans-masculine or male-to-female (MTF) trans-feminine spectrum according to their natal sex (Reisner, Conron, et al., 2014). Overall, 62.62% (n = 258) of the sample were on the FTM trans-masculine spectrum, of which 50.39% (n = 139) had a non-binary gender identity; 37.38% (n = 154) of the sample were on the MTF trans-feminine spectrum, of which 23.38% (n = 36) had a non-binary identity. The majority of the sample was white, non-Hispanic (80.83%; n = 333) and more than half of participants (55.73%; n = 230) considered themselves to be from low SES backgrounds.

Participants were recruited via transgender-specific online and in-person venues. The majority (88%) were sampled online via transgender electronic listservs, emails, web postings at local community-based websites, and social networking sites; 12% were surveyed in-person using onsite electronic tablets at transgender community events and other relevant local social programs. Eligible participants were ages 18 years or older; self-identified as transgender/gender nonconforming (e.g., had a gender identity/expression that differs from assigned sex at birth); lived in Massachusetts for at least three months in the last year; and had the ability to read/write in either English or Spanish. All participants provided consent before beginning the survey. Participants could opt to be entered into a community raffle for two tablet computers. All study activities were IRB-approved. Additional details on the study can be found elsewhere (Author).

Measures

Victimization

Discrimination experiences were assessed with the 11-item Everyday Discrimination Scale, which assesses the frequency of participants’ experiences of everyday discrimination in the past 12 months on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Very often). Sample items include: “You have been treated with less courtesy than other people;” “You have received poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores;” “People have acted as if they think you are not smart” (Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005; Williams et al., 1997). Items were summed and scores ranged from 0 to 44, with higher scores indicating higher levels of everyday discrimination experiences (α = .93; M = 19.88; SD=9.58). In previous research with gay and bisexual men, scores ranged from 0 to 45 (M = 12.6; SD=8.2) and Cronbach’s α was .90 (Gamarel, Reisner, Parsons, & Golub, 2012). Further, in samples of sexual and gender minority participants, discrimination scores were positively correlated with depressive distress, anxiety, and substance use (Gamarel, Reisner, Laurenceau, Nemoto, & OPerario, 2014; Gamarel et al., 2012; Gordon & Meyer, 2008; Reisner, Gamarel, Nemoto, & Operario, 2014).

Bullying was assessed using a measure previously developed and tested in transgender samples (Reisner, Greytak, et al., 2015; Ybarra, Diener-West, & Leaf, 2007). A 5-item measure was used to assess how often participants had been bullied or harassed by someone near their age prior to age 18: in person, by phone (call on a cell phone or landline), by text message, online, or some other way. Response options for each question were captured on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 5 (All the Time). Item responses were summed to create a continuous indicator of bullying (α = .81). Prior research comparing transgender and cisgender youth has found this scale to be highly reliable (α =.94) and associated with increased odds of alcohol use, marijuana use, and non-marijuana illicit drug use (Reisner, Greytak, et al., 2015).

Verbal harassment by family and physical assault by family were assessed using two adapted indicators of minority stress in sexual minority youth (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002). Participants were asked to indicate whether they had “ever been verbally harassed by family members” and “ever been physically assaulted by family members” both in their lifetime (yes/no) and within the past 12 months (yes/no). Participants were coded as having been verbally harassed by their family in their lifetime, including the past 12 months (yes/no). Participants were coded as having experienced family assault if they had experienced family assault in their lifetime, including in the past 12 months (yes/no). Prior research with sexual minority youth has found positive correlations between similar indicators of sexual minority-related stress and anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and conduct problems (Rosario et al., 2002).

Childhood sexual abuse was queried by asking: “Were you ever sexually abused as a child under age 15 years-old?” Responses were coded as 1 (Yes) versus 0 (No). Similarly, intimate partner violence was assessed with the item: “Have you ever been slapped, punched, kicked, beaten up, or otherwise physically or sexually hurt by your spouse (or former spouse), a boyfriend/girlfriend, or some other intimate partner?” Responses were coded as 1 (Yes) versus 0 (No). In the present sample, 33.3% of participants reported having experienced intimate partner violence and 33.1% reported having experienced childhood sexual abuse. These items were used in a prior study with transgender individuals (Reisner, Falb, Wagenen, Grasso, & Bradford, 2013) where 25.8% of the sample reported intimate partner violence and 54.8% reported childhood abuse (physical, sexual, and verbal combined). These items are similar to other screening instruments used to assess abuse in clinical settings (Basile, Hertz, & Back, 2007; Hulme, 2004; McFarlane, Parker, Soeken, & Bullock, 1992). Previous use of these items with sexual and gender minority populations have found positive associations with adverse mental health outcomes (Reisner et al., 2013).

Depressive symptomology

Participants completed the 10-item Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1993; Radloff, 1977) to assess past-week depressive symptomology. The CES-D-10 has been shown to correlate highly with the 20-item CES-D (r = .84-.91; p < .01) (Carpenter et al., 1998). Response options ranged from 0 (Rarely or none of the time) to 3 (All of the time) (Andresen et al., 1993). Scores were summed such that higher scores indicated greater depressive symptomology. In the current dataset, Cronbach’s α was .88, which is consistent with a previous study of transgender sex workers (α = .84) (Reisner et al., 2009) and validation studies with cisgender adolescents (α =.85) (Bradley, Bagnell, & Brannen, 2010) and HIV-infected adults (α =.88) (Zhang et al., 2012). The mean depressive score of the sample was 12.88 (SD = 9.60), which is higher than studies of cisgender adolescents (M=9.3; SD = 6.19) (Bradley et al., 2010)

Avoidant coping

Participants were administered the escape-avoidance subscale from the Revised Ways of Coping Questionnaire (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985). The 7-item scale asked participants to indicate the degree to which they currently use a variety of strategies to deal with stressful situations. Sample items included, “Hope a miracle happens,” “Avoid being with people,” and “Sleep more than usual.” Responses ranged on a 5-point scale from 0 (I never do it) to 4 (I always do it). Responses were summed to create a continuous coping score (range = 0 to 28) where higher scores indicate greater use of avoidant coping strategies. Cronbach’s α for the sample was .78, which is higher than validation studies with adolescent and middle-aged cisgender samples (α = 0.72) (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985, 1986). The mean (12.86; SD = 12.5) for the current sample was higher than that of cisgender youth (M = 5.75, SD = 2.05) (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985) and cisgender, middle-age, married men and women (M = 3.18, SD = 2.48) (Folkman & Lazarus, 1986). Further, in prior longitudinal research with cisgender, married adults, participants used more avoidant coping strategies when faced with situations threatening their physical health and stressful situations perceived to be unchangeable or outside their control (Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986).

Data Analysis

Using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2013), distributions of individual items were assessed, including missingness. Across the sample of 412 participants, 147 participants were missing responses to one or more items on a study measure, while the remaining 265 participants were missing no data. Missing data by scale ranged from a low of zero missing data points out of 4,532 possible data points on the everyday discrimination scale, to a high of 53 missing data points out of 412 possible data points for the family assault item. The other scales ranged from 1.2% to 11.2% missing data points per scale out of all possible data points. Given the amount of missing data, and the fact that patterns of missingness violated the missing completely at random assumption required for valid statistical inferences using listwise deletion (Allison, 2001; Allison, 2003), missing data were multiply imputed in SAS using PROC MI. A fully conditional specification imputation method was used, which has been shown to perform well in many different scenarios of missingness (Lee & Carlin, 2010; Van Buuren, 2007; Van Buuren, Brand, Groothuis-Oudshoorn, & Rubin, 2006). All subsequent analyses were conducted using the imputed data.

Descriptive analyses were performed in SPSS 21 (IBM Corp., 2012). Univariate descriptive statistics were used to summarize the overall distribution of variables with regard to mean, standard deviation (SD), frequency, and proportion (Table 1). We used a minimum of three indicators to model each latent variable (Weston & Gore, 2006). In modeling the latent victimization variable, we used six indicators: everyday discrimination, bullying, family verbal harassment, family assault, childhood sexual abuse, and intimate partner violence. We modeled the latent constructs of coping and depressive symptomology with item parcels as indicators. Specifically, in SPSS 21 we conducted an exploratory factor analysis of the avoidant coping and depressive symptomology (CESD) scales. Based on the results of each exploratory factor analysis, items were rank ordered from highest to lowest factor loading. To ensure a similar magnitude of average factor loadings across parcels, the highest factor loadings were grouped with the lowest factor loadings in counterbalancing order (Tebbe & Moradi, 2016).

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics for victimization, avoidant coping and depressive distress symptomology.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | ||||||||||||||

| 1. Everyday Discrimination | 1.00 | .41** | .35** | .25** | .27** | .16** | .31** | .30** | .16** | .29** | .42** | .44** | .32** | .40** |

| 2. Bullying | 1.00 | .35** | .32** | .25** | .20** | .16** | .18** | .11** | .09** | .25** | .26** | .18** | .25** | |

| 3. Family Harassment a | 1.00 | .45** | .15** | .25** | .15** | .15** | .14** | .08** | .22** | .25** | .19** | .17** | ||

| 4. Family Assault a | 1.00 | .22** | .28** | .16** | .15** | .14** | .08** | .17** | .19** | .15** | .10** | |||

| 5. Childhood Sexual Abuse a | 1.00 | .20** | .12** | .11** | .07** | .10** | .25** | .24** | .24** | .20** | ||||

| 6. Intimate Partner Violence a | 1.00 | .08** | −0.01 | 0.01 | .14** | .14** | .12** | .12** | .08** | |||||

| 7. Avoidant Coping b | 1.00 | .85** | .78** | .82** | .53** | .47** | .45** | .51** | ||||||

| 8. Coping Parcel 1 | 1.00 | .44** | .58** | .48** | .40** | .43** | .47** | |||||||

| 9. Coping Parcel 2 | 1.00 | .49** | .30** | .30** | .23** | .30** | ||||||||

| 10. Coping Parcel 3 | 1.00 | .53** | .48** | .46** | .50** | |||||||||

| 11. Depressive Symptomology c | 1.00 | .90** | .90** | .90** | ||||||||||

| 12. Depressive Symptoms Parcel 1 | 1.00 | .71** | .73** | |||||||||||

| 13. Depressive Symptoms Parcel 2 | 1.00 | .68** | ||||||||||||

| 14. Depressive Symptoms Parcel 3 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.94 | 0.83 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.78 | -- | -- | -- | 0.88 | -- | -- | -- |

| Mean or % | 19.88 | 5.62 | 49 | 19.7 | 31.8 | 33.3 | 12.83 | 4.68 | 3.6 | 4.55 | 12.89 | 3.8 | 4.15 | 3.5 |

| SD or n | 9.58 | 4.19 | 202 | 81 | 131 | 137 | 5.45 | 2.62 | 2.2 | 1.84 | 6.72 | 2.46 | 2.27 | 2.29 |

| Possible Range | 0-44 | 0-20 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0-28 | 0-12 | 0-8 | 0-8 | 0-20 | 0-9 | 0-9 | 0-9 |

p < .05

p < .01

For family assault, family harassment, intimate partner violence, and childhood sexual abuse, the percentage and number of participants in the “yes” category for these binary variables are displayed. For all other variables that have continuous distributions, means and SDs are displayed. Cronbach’s α only reported for continuous scales.

Avoidant Coping = overall escape-avoidance sum score from the Ways of Coping scale.

Depressive Symptomology= overall scale sum score from the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression scale.

Next, we used AMOS 23 (Arbuckle, 2014) to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the measurement model to ensure that all indicators adequately measured their corresponding latent construct. In this model, the six victimization indicators, three coping parcels, and three depressive symptomology parcels described above were modeled to load onto their respective latent variables, and the latent variables were allowed to correlate. To determine the fit of the hypothesized model to the data, we examined the non-normed fit index (NFI) and comparative fit index (CFI: .90 - .95 = acceptable; > .95=excellent); the root mean square error of approximation with 90% confidence intervals (RMSEA: < .06 = excellent); and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR: < .08 = excellent) (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kenny, 2015; Kline, 2010; West, Finch, & Curran, 1995). We also examined modification indices to detect items that had potential residual correlations and other elements of model misfit.

Next, we tested the hypothesized structural mediation model. First, we tested a full mediation model with direct paths from victimization to avoidant coping and from avoidant coping to depressive distress symptoms. The full model did not have a direct path from victimization to depressive distress symptoms. Following the recommendations of Weston and Gore (2006), we compared the full mediation model to a partial mediation model that included direct paths from victimization to both avoidant coping and depressive distress symptoms and from avoidant coping to depressive distress symptoms. Using the model fit indicators described above, we then identified the best fitting model.

After determining the best fitting model, we tested our hypothesis that victimization is indirectly and positively associated with depressive symptomology through avoidant coping in a structural equation model using AMOS 23. Bootstrapping was used to test the significance of the indirect (mediated) associations (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). We generated 2,000 random samples from our dataset to construct a 95% standardized confidence interval for the mediated association of victimization on depressive symptomology through avoidant coping. The amount of variability (R2) of the latent mediator and outcome accounted for by the model variables was assessed; the NFI, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR were used to evaluate the overall fit of the model.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Measurement Model

(Tebbe & Moradi, 2016; Weston & Gore, 2006) Table 2 displays both the unstandardized and standardized results of the CFA for victimization, avoidant coping, and depressive symptomology. The measurement model fit the data adequately: X2 (df = 41) = 389.15, p < .001; NFI = .95; CFI = .96; RMSEA =.06 (90% CI = .05, .07); SRMR = .04. The significant chi-square statistic was the only indication of model misfit and is known to be sensitive to large sample sizes (Kenny, 2015). All indicators for victimization, avoidant coping, and depressive symptomology had loadings greater than or equal to .40, were in the expected direction, and were statistically significant.

Table 2.

Measurement model of victimization, avoidant coping, and depressive symptomology.

| Unstandardized | Standardized | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Variables | B | SE | B | SE |

| Victimization | ||||

| Everyday Discrimination | 1.00 | a | .85 | a |

| Bullied | .26 | .02 | .51 | .03 |

| Family Harassment | .02 | .002 | .56 | .03 |

| Family Assault | .03 | .002 | .49 | .03 |

| Childhood Sexual Abuse | .03 | .002 | .49 | .03 |

| Intimate Partner Violence | .02 | .002 | .40 | .03 |

| Avoidant Coping | ||||

| Coping Parcel 1 | 1.00 | a | .74 | a |

| Coping Parcel 2 | .62 | .03 | .55 | .03 |

| Coping Parcel 3 | .75 | .03 | .80 | .03 |

| Depressive Symptomology | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms Parcel 1 | 1.00 | a | .87 | a |

| Depressive Symptoms Parcel 2 | .95 | .02 | .81 | .02 |

| Depressive Symptoms Parcel 3 | 1.11 | .02 | .84 | .02 |

|

| ||||

| Model Fit: X2 = 389.15 (df = 41),p < .001 | RMSEA (CI) .06 (.05, .07) |

NFI .95 |

CFI .96 |

SRMR .04 |

Note. X2 = Chi-Square, df= degrees of freedom; RMSEA=root mean square error of approximation; CI = 90% confidence interval; NFI = non-normed fit index; CFI=comparative fit index; SRMR= standardized root mean square residual. All indicators significant, p < .001.

Standard errors were not calculated for the first indicator in the unstandardized model because its factor loading was fixed to 1 in order to establish the scale of the factor.

Structural Model

Results of the full mediation model demonstrated adequate fit: X2 (df = 42) = 556.55, p < .001; NFI = .93; CFI = .94; RMSEA =.08 (90% CI = .07, .08); SRMR = .06. The full mediation model accounted for 20.1% of the variance in avoidant coping and 55.5% of the variance in depressive symptomology. Fit of the partial mediation model was better than the full mediation model: X2 (df = 41) = 389.15, p < .001; NFI = .95; CFI = .96; RMSEA =.06 (90% CI = .05, .07); SRMR = .04. The partial mediation model accounted for 13.2% of the variance in avoidant coping and 55.4% of the variance in depressive symptomology. The difference between the two models was significant: Δ X2 (df = 1) = 167.40, p < .001; thus, the partial mediation model was retained for testing the hypothesized mediation.

Test of Mediation

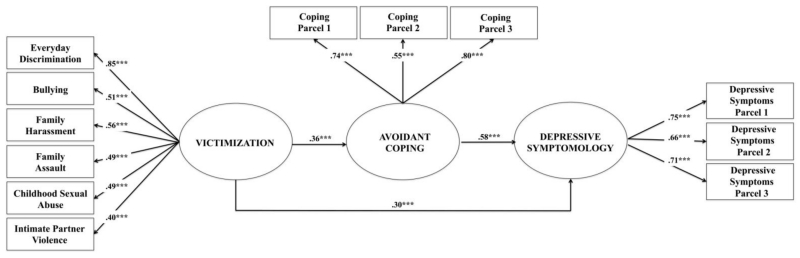

Figure 2 depicts the final mediation model examining the direct association of victimization and depressive symptomology and indirect association through avoidant coping. Model fit statistics mirrored those of the partial mediation structural model, as did the percent of variance explained by the model (Figure 2). As hypothesized, experiences of victimization was positively associated with avoidant coping (β = .36, SE = .03, p < .001) and avoidant coping was also positively associated with depressive symptomology (β = .58, SE = .02, p < .001). Victimization also had a significant direct association with depressive symptomology (β = .30, SE = .03, p < .001), indicating that a portion of its association with depressive symptomology is not mediated through avoidant coping. Bootstrapping was used to test the significance of the indirect association of victimization on depressive symptomology through avoidant coping. The standardized indirect association of this path was 0.21 (bootstrap 95% confidence interval = .18, .24; p < .001), indicating that avoidant coping partially mediated the relationship between victimization and depressive symptomology in this sample.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model depicting avoidant coping as a partial mediator of the association between victimization and depressive symptomology in a sample of transgender adults.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Indirect Effect = .21 (95% CI = .18, .24), p < 0.001; Model Fit: X2 (df = 41) = 389.10, p < .001; NFI = .95; CFI = .96; RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05, .07); SRMR = .04

Discussion

We tested a model of avoidant coping in a large, community sample of transgender adults. We found support for all of the model’s hypothesized associations. Specifically, positive associations were found among victimization, avoidant coping, and depressive symptomology such that experiences of victimization were significantly and positively associated with both engaging in avoidant coping and past-week depressive symptoms. Participants’ use of avoidant coping was also significantly and positively associated with their level of depressive symptomology. As hypothesized, avoidant coping was found to partially mediate the relationship between victimization and depressive symptomology, such that when avoidant coping was accounted for, the relationship between victimization and depressive symptomology was significantly reduced. This is the first study to our knowledge to demonstrate that avoidant coping partially accounts for the positive association between victimization and depressive symptomology in a sample of transgender adults. These mediational findings are consistent with past research with non-transgender samples (Kaysen et al., 2014; Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014; Szymanski & Owens, 2008; Thomas et al., 2008) and joins a growing body of literature suggesting that avoidant coping may contribute to the psychological sequelae of victimization. Findings have implications for clinical care and interventions for transgender individuals who have been victimized, including the potential to mitigate the adverse psychological impact of victimization by addressing coping.

While previous research has documented a positive association between transgender individuals’ experiences of discrimination and use of avoidant coping strategies (e.g., Mizock & Mueser, 2014), discrimination (e.g., being denied a job, healthcare services, or housing) represents a single conceptualization of victimization and does not necessarily account for experiences of violence such as physical or sexual assault. This study extends prior discrimination and coping research with transgender individuals (Mizock & Mueser, 2014) by demonstrating that a latent victimization variable comprised of multiple indicators of victimization (i.e., discrimination, bullying, family verbal harassment, family physical assault, childhood sexual abuse, and intimate partner violence) is positively associated with avoidant coping. The present study also supports existing coping and mental health research with transgender people (Budge et al., 2013) by demonstrating a positive association between avoidant coping strategies and depressive symptoms in a sample of transgender adults. Additionally, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to show that avoidant coping partially mediates the relationship between victimization and depressive symptoms in transgender adults. Prior research among cisgender individuals suggests that the more a victimized person fears the threat of victimization and attempts to avoid exposure to mistreatment, the stronger and more persistent the fear of victimization may become (Abramowitz et al., 2001; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Merwin et al., 2009). Thus, for victimized individuals who engage in avoidant coping, depressive distress may develop in response to the unremitting psychological threat of future victimization (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Merwin et al., 2009) and limit one’s self-efficacy to prevent future experiences of victimization through less avoidant means. Future research is needed that examines both the mechanisms through which avoidant coping may contribute to depressive distress in transgender individuals, and the strategies transgender people use to remain resilient in the face of victimization.

In light of the results of the adapted minority stress model examined here, along with prior research demonstrating the significant influences of victimization on transgender individuals’ mental health (e.g. Stotzer, 2009; White Hughto, 2015 for reviews), individual-level interventions aimed at helping transgender people develop alternative means of coping might reduce the psychological effects of victimization (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Thoits, 1991). For example, mental health professionals might help transgender individuals who have experienced victimization understand how these experiences contribute to avoidant coping behaviors and workshop strategies to help transgender clients to better navigate anticipated or enacted victimization in order to avoid the potential onset of depressive distress (Brown, Hernandez, & Villarreal, 2011; Pachankis, 2009, 2014). Finally, transgender individuals may also benefit from individual or group-based self-affirmation interventions that help individuals who have been victimized manage the fear of future mistreatment by realizing they have the skills and strengths to prevent or manage these experiences through less avoidant means (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Greene, Britton, & Fitts, 2014; Leichsenring, Beutel, & Leibing, 2007; Resick & Schnicke, 1992). Additionally, empowerment interventions (Zimmerman, 1995), such as the ESTEEM intervention for young gay and bisexual men (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren, & Parsons, 2015) have effectively reduced the negative emotional and behavioral consequences of stigma to improve mental health. An adaptation of the ESTEEM intervention, along with the other individual-level interventions discussed here, warrant future development and testing in transgender populations. Finally, while individual-level interventions are essential to reducing behavioral responses to victimization and associated depressive symptomology, structural interventions are also needed to reduce transgender stigma at the societal-level in order to fully eliminate victimization and its related mental health sequelae among transgender individuals.

The present investigation contributes to the literature by using a large sample of transgender adults and a comprehensive assessment of exposure to victimization throughout the life-course. Yet, study limitations must be noted. First, the cross-sectional nature of these data means that causality cannot be assumed from the current mediation model, especially given evidence that mental health status may influence reports of stress exposure (Meyer, 2003a; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). While ethical issues make it difficult to experimentally test the model used here, longitudinal designs would allow researchers to determine whether avoidant coping strategies develop over time following experiences of victimization. While the racial/ethnic distribution of this convenience sample (81% white) was similar to the racial/ethnic distribution of residents of Massachusetts (82% white) (U.S. Census, 2016), it is possible that our findings might not be generalizable to samples largely comprised of racial/ethnic minorities or recruited in other locations; future testing of the model in more diverse populations is warranted. In addition, the study utilized a continuous measure of depressive symptomology rather than a diagnostic assessment. However, substantial research documents the comparative benefit that continuous, versus discrete measurement provides to statistical power and the reliable and valid assessment of depression (Beauchaine, 2007). Another limitation is the use of the single item measures employed here (i.e., intimate partner violence, childhood sexual abuse, family harassment, and family assault) as we were unable to determine the specific timeframe during which the events occurred, the frequency with which they occurred, or the perpetuators of these acts. Future research should aim to develop and validate more robust (e.g., type, setting, frequency, perpetrator) measures of victimization among transgender samples. Finally, studies that simultaneously assess victimization and perpetration may provide useful insights concerning the complex interplay of victimization across the life-course in transgender communities.

The present study provides evidence of factors positively associated with depressive symptomology among transgender adults and identifies modifiable targets for culturally responsive interventions. Individual interventions that help transgender people cope with the impact of victimization through less avoidant means and structural interventions that target the sources of stigma at the societal-level may help to prevent the onset of victimization-related depressive symptoms; such interventions necessitate future development and testing among transgender populations. Finally, uncovering additional mechanisms underlying vulnerability to and protection against depressive symptoms represents a key direction for future clinically-relevant research with this population.

Public Significance Statement.

Victimization is positively associated with depressive symptomology directly and indirectly through avoidant coping among transgender adults. Avoidant coping represents a potential intervention target for clinicians aiming to reduce the mental health sequelae of victimization in this highly stigmatized and vulnerable population.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Tolin DF, Street GP. Paradoxical effects of thought suppression: A meta-analysis of controlled studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21(5):683–703. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00057-x. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00057-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(4):545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen E, Malmgren J, Carter W, Patrick D. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1993;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos (Version 23.0) [Computer Program] IBM SPSS; Chicago: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore RD, Deaux K, McLaughlin-Volpe T. An organizing framework for collective identity: articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(1):80–114. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal S, Van Oost P, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Crombez G. Avoidant coping as a mediator between self-reported sexual abuse and stress-related symptoms in adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(8):883–897. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00137-6. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile K, Hertz M, Back S. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings: version 1. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.popline.org/node/199321.

- Beauchaine TP. Methodological article: A brief taxometrics primer. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36(4):654–676. doi: 10.1080/15374410701662840. doi:10.1080/15374410701662840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers C, Meyer B. Thought suppression and depression risk. Cognition and Emotion. 2004;18(6):859–867. doi:10.1080/02699930341000220. [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Miner MH, Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):943–951. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KL, Bagnell AL, Brannen CL. Factor validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Stuies Depression 10 in adolescents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2010;31(6):408–412. doi: 10.3109/01612840903484105. doi:10.3109/01612840903484105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B, Hernandez VR, Villarreal Y. Connections: A 12-session psychoeducational shame resilience curriculum. In: Dearing R, Tangney J, editors. Shame in the therapy hour. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2011. pp. 355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Adelson JL, Howard KA. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(3):545–557. doi: 10.1037/a0031774. doi:10.1037/a0031774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J, Andrykopwski M, Wilson J, Hall LA, Rayens MK, Sachs B, Cunningham L. Psychometrics for two short forms of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1998;19:481–494. doi: 10.1080/016128498248917. doi:10.1080/016128498248917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Guzman R, Katz M. HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use, and mental health status of transgender persons: Implications for public health intervention. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):915–921. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: Some evidence and its implications for theory and research. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(1):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factor RJ, Rothblum ED. A study of transgender adults and their non-transgender siblings on demographic characteristics, social support, and experiences of violence. Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2008;3(3):11–30. doi: 10.1080/15574090802092879. doi:10.1080/15574090802092879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99(1):20–35. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48(1):150–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.1.150. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Stress processes and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95(2):107–113. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.2.107. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.95.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(3):466–475. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50(5):992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Reisner SL, Laurenceau JP, Nemoto T, OPerario D. Gender minority stress, mental heath, and relationship quality: A dyadic investigation of transgener women and their cisgender male partners. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28(4):437–447. doi: 10.1037/a0037171. doi:10.1037/a0037171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Reisner SL, Parsons JT, Golub SA. Association between socioeconomic position discrimination and psychological distress: Findngs from a community-based sample of gay and bisexual men in New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(11):2094–2101. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300668. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AR, Meyer IH. Gender nonconformity as a target of prejudice, discrimination, and violence against LGB individuals. Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2008;3(3):55–71. doi: 10.1080/15574090802093562. doi:10.1080/15574090802093562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis LA, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.thetaskforce.org/static_html/downloads/reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf.

- Greene DC, Britton PJ, Fitts B. Long-term outcomes of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender recalled school victimization. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2014;92(4):406–417. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00167.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20(10):1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012;43(5):460–467. doi:10.1037/a0029597. [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Stabl MA, Stemmler M, Petersen AC. Approach and avoidant coping: Implications for adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24(6):649–665. doi:10.1007/BF01536949. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. t., Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme PA. Retrospective measurement of childhood sexual abuse: A review of instruments. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9(2):201–217. doi: 10.1177/1077559504264264. doi:10.1177/1077559504264264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Kulesza M, Balsam KF, Rhew IC, Blayney JA, Lehavot K, Hughes TL. Coping as a mediator of internalized homophobia and psychological distress among young adult sexual minority women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1(3):225–233. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000045. doi:10.1037/sgd0000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Measuring model fit. 2015 Retrieved from http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm.

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. Principles and practice of Structural equation modeling. 3rd edition Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress appraisal and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Carlin JB. Multiple imputation for missing data: fully conditional specification versus multivariate normal imputation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;171(5):624–632. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp425. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring F, Beutel M, Leibing E. Psychodynamic psychotherapy for social phobia: a treatment manual based on supportive-expressive therapy. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. 2007;71(1):56–83. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2007.71.1.56. doi:10.1521/bumc.2007.71.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi E. Varieties of transgender/transsexual lives and their relationship with transphobia. Journal of Homosexuality. 2009;56(8):977–992. doi: 10.1080/00918360903275393. doi:10.1080/00918360903275393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39(1):99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy: Severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA. 1992;267(23):3176–3178. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.23.3176. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480230068030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merwin RM, Rosenthal MZ, Coffey KA. Experiential avoidance mediates the relationship between sexual victimization and psychological symptoms: Replicating findings with an ethnically diverse sample. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2009;33(5):537–542. doi:10.1007/s10608-008-9225-7. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2003a;93(2):262–265. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003b;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social status confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67(3):368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L, Lewis TK. Trauma in transgender populations: Risk, resilience, and clinical care. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2008;8(3):335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L, Mueser KT. Employment, mental health, internalized stigma, and coping with transphobia among transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1(2):146–158. doi:10.1037/sgd0000029. [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and HIV-affected intimate partner violence. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.avp.org/storage/documents/ncavp2013ipvreport_webfinal.pdf.

- Nemoto T, Bodeker B, Iwamoto M. Social support, exposure to violence and transphobia, and correlates of depression among male-to-female transgender women with a history of sex work. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(10):1980–1988. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197285. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.197285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman ML, Holden GW, Delville Y. Coping with the stress of being bullied: Consequences of coping strategies among college students. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2010;2(2):205–2011. doi:10.1177/1948550610386388. [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L, Hwahng S, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Mason M, Macri M, Becker J. Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the life course of male-to-female transgender persons. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47(1):12–23. doi: 10.1080/00224490903062258. doi:10.1080/00224490903062258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. The use of cognitive-behavioral therapy to promote authenticity. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy. 2009;5(4):28–38. doi:10.14713/pcsp.v5i4.997. [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2014;21(4):1–26. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12078. doi:10.1111/cpsp.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina HJ, Safren SA, Parsons JT. LGB-affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(5):875–889. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000037. doi:10.1037/ccp0000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Biello K, Rosenberger JG, Austin SB, Haneuse S, Perez-Brumer A, Mimiaga MJ. Using a two-step method to measure transgender identity in Latin America/the Caribbean, Portugal, and Spain. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(8):1503–1514. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0314-2. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0314-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Biello K, White Hughto JM, Kuhns L, Mayer KH, Garofalo R, Mimiaga MJ. Psychiatric diagnoses and comorbidities in a diverse, multicity cohort of young transgender women baseline findings from Project Lifeskills. JAMA. 2016;170(5):481–486. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0067. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Conron KJ, Tardiff LA, Jarvi S, Gordon AR, Austin SB. Monitoring the health of transgender and other gender minority populations: Validity of natal sex and gender identity survey items in a US national cohort of young adults. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1224–1234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1224. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Falb KL, Wagenen AV, Grasso C, Bradford J. Sexual orientation disparities in substance misuse: the role of childhood abuse and intimate partner violence among patients in care at an urban community health center. Substance Use and Misuse. 2013;48(3):274–289. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.755702. doi:10.3109/10826084.2012.755702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Gamarel KE, Nemoto T, Operario D. Dyadic effects of gender minority stressors in substance use behaviors among transgender women and their non-transgender male partners. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1(1):63–71. doi: 10.1037/0000013. doi:10.1037/0000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Greytak EA, Parsons JT, Ybarra ML. Gender minority social stress in adolescence: disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. Journal of Sex Research. 2015;52(3):243–256. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.886321. doi:10.1080/00224499.2014.886321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Bland S, Mayer KH, Perkovich B, Safren SA. HIV risk and social networks among male-to-female transgender sex workers in Boston, Massachusetts. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20(5):373–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.06.003. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Vetters R, White J, Cohen E, LeClerc M, Zaslow S, Mimiaga M. Laboratory-confirmed HIV and STI seropositivity and risk behavior among sexually active transgender patients at an adolescent and young adult urban community health center. AIDS Care. 2015;27(8):1031–1036. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1020750. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1020750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, White JM, Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ. Sexual risk behaviors and psychosocial health concerns of female-to-male transgender men screening for STDs at an urban community health center. AIDS Care. 2014;26(7):857–864. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.855701. doi:10.1080/09540121.2013.855701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(5):748–756. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.748. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Gay-related stress and emotional distress among gay, lesbian and bisexual youths: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(4):967–975. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.967. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS 9.4 [Computer Program] Cary, NC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stotzer RL. Violence against transgender people: A review of United States data. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14(3):170–179. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.006. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Henrichs-Beck C. Exploring sexual minority women’s experiences of external and internalized heterosexism and sexism and their links to coping and distress. Sex Roles. 2014;70(1):28–42. doi:10.1007/s11199-013-0329-5. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Owens GP. Do coping styles moderate or mediate the relationship between internalized heterosexism and sexual minority women’s psychological distress? Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32(1):95–104. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00410.x. [Google Scholar]

- Tebbe EA, Moradi B. Suicide risk in trans populations: An application of minority stress theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1037/cou0000152. Ahead of Print. doi:10.1037/cou0000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa RJ, Jimenez CL, Rankin S. Risk and resilience during transgender identity development: The effects of awareness and engagement with other transgender people on affect. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2014;18(1):31–46. doi:10.1080/19359705.2013.805177. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Gender differences in coping with emotional distress. In: Eckenrode J, editor. The social context of coping. Springer; New York, NY: 1991. pp. 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, Speight SL. Gendered racism, psychological distress, and coping styles of African American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(4):307–314. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.307. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Quick facts: Massachusetts. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/25.

- Van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2007;16(3):219–242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463. doi:10.1177/0962280206074463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren S, Brand JPL, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Rubin DB. Fully conditional specification in multivariate imputation. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation. 2006;76(12):1049–1064. doi:10.1080/10629360600810434. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EF, Myers MG, McIninch JL. Stress-coping and temptation-coping as predictors of adolescent substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(6):769–779. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00058-1. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(99)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In: Hoyle H, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and application. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Weston R, Gore PA. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist. 2006;34(5):719–751. doi:10.1177/0011000006286345. [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Murchison G, Clark K, Pachankis JE, Reisner SL. Geographic and individual differences in healthcare access for U.S. transgender adults: A multilevel analysis. LGBT Health. 2016 doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0044. ahead of print. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 2015;147:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and hental Health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. doi:10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Stress and coping in early adolescence: relationships to substance use in urban school samples. Health Psychology. 1986;5(6):503–529. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.5.6.503. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.5.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Diener-West M, Leaf PJ. Examining the overlap in internet harassment and school bullying: Implications for school intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41(6):S42–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.004. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, O’Brien N, Forrest JI, Salters KA, Patterson TL, Montaner JSG, Lima VD. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40793–e40793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040793. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23(5):581–599. doi: 10.1007/BF02506983. doi:10.1007/BF02506983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]