Abstract

Objective

To quantify the influence of various patient characteristics on early smoking cessation in order to better identify target populations for focused counseling and interventions.

Study Design

Population based retrospective cohort study of 1,003,532 Ohio live births over 7 years (2006–2012). Women who quit smoking in the 1st trimester were compared to those who smoked throughout pregnancy. Logistic regression estimated the strength of association between patient factors and smoking cessation.

Results

The factors most strongly associated with early smoking cessation were: Non-white race and Hispanic ethnicity, at least some college education, early prenatal care, marriage, and breastfeeding. Numerous factors commonly associated with adverse perinatal outcomes were found to have a negative association with smoking cessation: low educational attainment, limited or late prenatal care, prior preterm birth, age <20 yrs, age ≥35 yrs, and indicators of low SES. Additionally, the heaviest smokers (≥20 cig/day) were least likely to quit (adj RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.34, 0.36).

Conclusion

Early prenatal care and initiation of breastfeeding prior to discharge from the hospital are associated with increased relative risk of quitting early in pregnancy by 52% and 99%, respectively. Public health initiatives and interventions should focus on the importance of early access to prenatal care and education regarding smoking cessation for these particularly vulnerable groups of women who are at inherently high risk of pregnancy complications.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Smoking Cessation

OBJECTIVE

Smoking remains one of the most important modifiable risk factors associated with poor perinatal outcomes.1–5 When compared to other risk factors in the perinatal period, exposure to tobacco smoke is considered to be amongst the most harmful and is associated with high rates of long and short term morbidity and mortality for mother and child.6 In 2002, 5–8% of preterm deliveries, 13–19% of term infants with growth restriction, 5–7% of preterm-related deaths, and 23–24% of SIDS deaths were attributable to prenatal smoking in the United States.7 According to Healthy people 2020, only 18.9% of pregnant female smokers quit smoking during the first trimester and remained a quitter throughout pregnancy in 2010. The 2020 target for smoking cessation in pregnant females is 30%.8 In 2011, the prevalence of smoking early in pregnancy in Ohio was 23%, twice as high compared to the US national rate of 11.5%.9

A recently published study demonstrated that early smoking cessation in the first trimester has a favorable influence on IUGR risk compared to women who quit later in pregnancy10. Since our home state of Ohio has a much higher prevalence of pregnant smokers, our objective was to quantify the influence of various patient characteristics on early smoking cessation in order to better identify target populations for focused counseling and interventions.

STUDY DESIGN

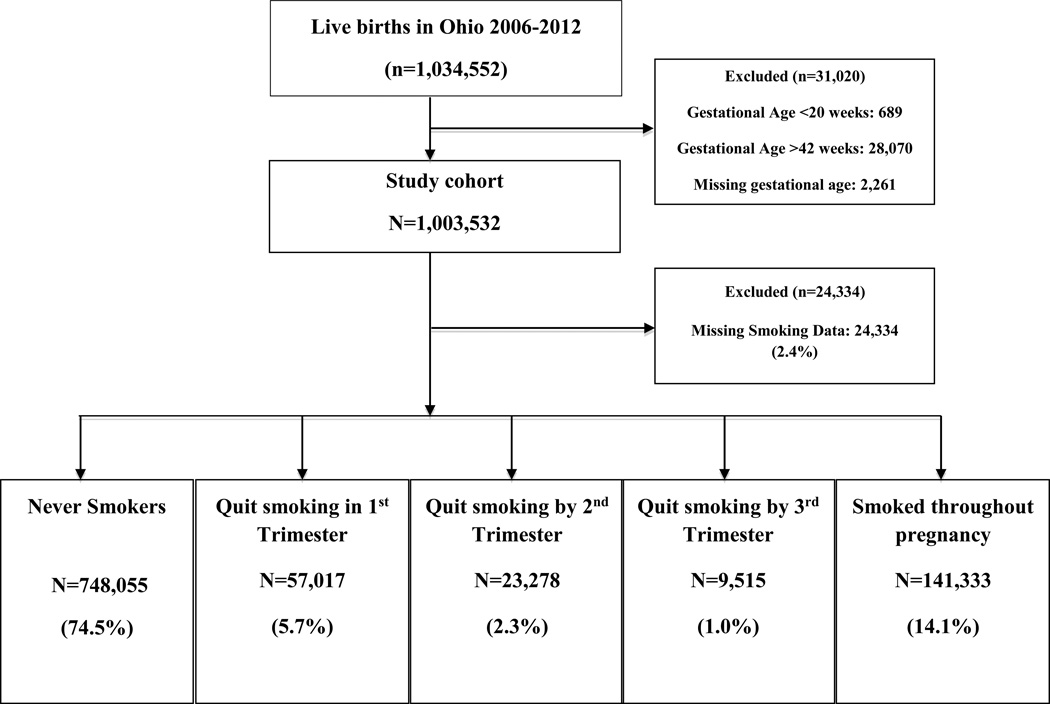

This study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board of the Ohio Department of Health, who provided us with a de-identified set of data, which included birth certificate data on 1,034,552 live births that occurred in Ohio over a 7 year period (2006–2012). The study was exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio. From this data set, we performed a population based retrospective cohort study aimed to identify factors associated with smoking cessation in pregnancy. Births that occurred before 20 weeks, after 42 weeks, and those with missing gestational age were excluded from analysis, see Figure 1. Gestational age was defined using the US vital statistics birth certificate variable obstetric estimate, which is the clinician’s best estimate of gestational age using a combination of the last menstrual period and earliest ultrasound measurement.11 Ohio implemented the newest (2003) version of the national birth certificate in 2006, which is why we requested the data set to include years 2006 and beyond.

Fig 1.

Flow Diagram of Exposure Groups

After exclusions, a study cohort of 1,003,532 births remained. Of this cohort, 24,334 (2.4%) had missing smoking data or insufficient data to classify into one of the smoking pattern groups (Figure 1), leaving the final studied population of 979,198. The U.S. birth certificate contains data on maternal tobacco smoking during four time periods: “three months before pregnancy”, “first three months of pregnancy”, “second three months of pregnancy”, and “third trimester of pregnancy”12 From this data, we created five exposure groups based on the mother’s self-reported smoking status: “never smoker”, “quit smoking in the 1st trimester”, “quit smoking by the 2nd trimester”, “quit smoking by the 3rd trimester”, and “smoked throughout pregnancy” (Figure 1). Quit in the 1st trimester included all women who reported ≥1 cigarette/day for the three months before pregnancy and 0 cigarettes/day for the remaining categories. Quit by the 2nd trimester included women who reported ≥1 cigarette/day in both the three months before pregnancy and first three months of pregnancy, however reported 0 cigarettes/day in the second three months of pregnancy and the third trimester. Quit by the 3rd trimester included women who reported smoking ≥1 cigarette/day in all categories through the second three months of pregnancy and 0 cigarettes/day in the third trimester. We considered any amount of smoking (≥1 cigarette per day) as a smoker.

Independent variables for this analysis included the following sociodemographic factors: mother’s level of educational attainment, maternal race, parity, age, marital status, and Medicaid and recipient of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Prenatal care variables included: limited prenatal care (≤5 total visits), first prenatal visit ≤12 weeks gestation, late initiation of prenatal care (>20 weeks gestation), no prenatal care, prior preterm birth, and heavy smoking before pregnancy (≥20 cigarettes/day). We also examined medical comorbidities such as: chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension/preeclampsia, pre-gestational diabetes and gestational diabetes. Selection of these variables were based on published literature regarding smoking cessation patterns in pregnancies and data available in the birth certificate.11–17,19 Overall, there was minimal missing data (≤3.1%) for most variables analyzed, including maternal age, race, educational attainment, WIC enrollment, pre-gestational diabetes and hypertension, gestational diabetes and hypertension, previous preterm birth, and marital status. BMI, Medicaid enrollment, and initiation of breastfeeding prior to hospital discharge had a slightly larger amount of missing data, 6.0%, 4.8%, and 6.2%, respectively. Gestational age at first prenatal visit contained the largest amount of missing data at 25%. There was also a small number of missing smoking data or smoking behaviors that didn’t fall within any of the 5 exposure groups (2.4%).

Maternal demographic, behavioral, medical and prenatal factors were compared between women who quit smoking early in pregnancy (1st trimester) and the referent group of women who smoked throughout pregnancy with chi square and t-tests. Multivariable logistic regression was then utilized to estimate the adjusted relative risk for quitting smoking in the first trimester after adjustment for all other variables in the regression model. Backward elimination approach was used and non-significant variables were sequentially removed from the full regressions model. The final model consisted of variables with significant differences noted in univariate comparisons and those with biologic plausibility. Births with missing data on covariates were not included in the regression models.

Analyses were performed using STATA 12.1 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Comparisons with p-value <0.05 and 95% confidence interval not inclusive of the null value 1.0 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

We analyzed 979,198 live birth records in this study. Of these, nearly a quarter of mothers (N=231,143; 23.6%) reported being cigarette smokers at some point during the pregnancy. Figure 1 categorizes the study population based on self-reported smoking in pregnancy, and in those who quit smoking, which trimester of pregnancy cessation occurred. Nonsmokers comprised the majority (74.5%) of the cohort, and 14.1% of women smoked throughout pregnancy. Few women, 5.7% of the study cohort, quit smoking at some time in the first trimester; presumably after they found out they were pregnant.

The majority of our study population (76.6%) consisted of non-Hispanic white women. This subset of women also appeared to have a higher likelihood of smoking in pregnancy (26.0%) compared to the non-white women studied (15.6%). Additionally, non-Hispanic white women were the least likely to quit smoking during pregnancy. Young mothers (<20 years) also had a higher prevalence of smoking during pregnancy (30.7%) compared to women in the age group of 20–34 years (24.4%) and ≥35 years (12.7%). Young maternal age also correlated with a higher frequency of smoking throughout pregnancy (17.9% vs 14.6% in 20–34 years of age and 7.7% in ≥35 years of age). Other factors associated with smoking throughout pregnancy were low educational attainment, unmarried, WIC and Medicaid recipients, limited prenatal care (≤5 visits) or late initiation of prenatal care (>20 weeks gestation), previous preterm birth, and those women who smoked >20 cigarettes/day (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maternal Characteristics

| Never smokers N=748,055 |

Quit in the 1st trimester N=57,017 |

Quit by the 2nd trimester N=23,278 |

Quit by the 3rd trimester N=9,515 |

Smoked throughout pregnancy N=141,333 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | |||||

| Mother's Race | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 554,477 (74.1%) |

47,384 (83.1%) |

18,882 (81.1%) |

7,679 (80.7%) |

121,297 (85.8%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 130,316 (17.4%) |

7,103 (12.5%) |

3,397 (14.6%) |

1,496 (15.7%) |

16,309 (11.5%) |

| Hispanic | 38,779 (5.2%) |

1,971 (3.5%) |

791 (3.4%) |

271 (2.8%) |

2,784 (2.0%) |

| Other | 23,162 (3.1%) |

495 (0.9%) |

175 (0.8%) |

51 (0.5%) |

692 (0.5%) |

| Primiparous | 295,599 (40.2%) |

28,776 (51.3%) |

11,542 (50.5%) |

4,312 (46.1%) |

43,912 (31.6%) |

| Maternal Age Group | |||||

| <20 | 66,905 (8.9%) |

6,508 (11.4%) |

3,767 (16.2%) |

1,615 (17.0%) |

17,804 (12.6%) |

| 20–34 | 576,966 (77.1%) |

46,794 (82.1%) |

18,252 (78.4%) |

7,354 (77.3%) |

113,906 (80.6%) |

| ≥35 | 104,184 (13.9%) |

3,715 (6.5%) |

1,259 (5.4%) |

546 (5.7%) |

9,623 (6.8%) |

| Socioeconomic Factors | |||||

| Less Than High School Diploma | 100,434 (13.4%) |

7,651 (13.4%) |

4,543 (19.5%) |

2,384 (25.1%) |

45,239 (32.0%) |

| Married | 492,589 (65.9%) |

25,432 (44.6%) |

7,229 (31.1%) |

2,417 (25.4%) |

40,451 (28.6%) |

| WICa | 257,374 (34.4%) |

28,180 (49.4%) |

14,050 (60.4%) |

6,175 (64.9%) |

96,173 (68.1%) |

| Medicaid | 216,961 (29.0%) |

25,180 (44.2%) |

13,108 (56.3%) |

6,145 (64.6%) |

96,713 (68.4%) |

| Prenatal Care | |||||

| Limited Prenatal Care (≤5 visits) | 54,472 (7.3%) |

3,583 (6.3%) |

1,878 (8.1%) |

1,114 (11.7%) |

17,911 (12.7%) |

| Early Initiation: First Visit ≤12 weeks Gestation |

428,750 (57.3%) |

34,163 (59.9%) |

11,979 (51.5%) |

4,376 (46.0%) |

65,956 (46.7%) |

| Late Initiation: First Visit >20 weeks Gestation |

44,144 (5.9%) |

2,903 (5.1%) |

1,684 (7.2%) |

855 (9.0%) |

12,883 (9.1%) |

| No Prenatal Care | 10,265 (1.4%) |

636 (1.1%) |

321 (1.4%) |

207 (2.2%) |

4,104 (2.9%) |

| Pregnancy Characteristics | |||||

| Previous Pre-term Birth | 25,043 (3.4%) |

1,689 (3.0%) |

784 (3.4%) |

492 (5.2%) |

7,527 (5.3%) |

| Multiple Gestation | 29,436 (3.9%) |

1,970 (3.5%) |

750 (3.2%) |

364 (3.8%) |

3,695 (2.6%) |

| Initiated Breastfeeding After Birth | 508,226 (67.9%) |

34,719 (60.9%) |

12,923 (55.5%) |

4,581 (48.2%) |

52,368 (37.1%) |

| Smoking ≥ 1ppd (≥20 cigarettes/day) |

0 | 17,822 (31.3%) |

10,280 (44.2%) |

5,035 (52.9%) |

81,072 (57.4%) |

| Medical Factors | |||||

| Underweight (prepregnancy) BMI <18.5 |

25,315 (3.4%) |

2,574 (4.5%) |

1,357 (5.8%) |

649 (6.8%) |

10,410 (7.4%) |

| Normal weight(prepregnancy) BMI 18.5–24.9 |

345,295 (46.2%) |

25,804 (45.3%) |

10,344 (44.4%) |

4,236 (44.5%) |

61,201 (43.3%) |

| Overweight (prepregnancy) BMI 25–29.9 |

172,334 (23.0%) |

13,448 (23.6%) |

5,206 (22.4%) |

1,957 (20.6%) |

30,563 (21.6%) |

| Obese (prepregnancy) BMI ≥30 |

205,111 (27.4%) |

15,191 (26.6%) |

6,371 (27.4%) |

2,673 (28.1%) |

39,159 (27.7%) |

| Pre-gestational Diabetes | 5,983 (0.8%) |

442 (0.8%) |

223 (1.0%) |

87 (0.9%) |

1,301 (0.9%) |

| Gestational Diabetes | 41,418 (5.5%) |

3,348 (5.9%) |

1,323 (5.7%) |

533 (5.6%) |

6,857 (4.9%) |

| Chronic Hypertension | 14,446 (1.9%) |

1,049 (1.8%) |

414 (1.8%) |

214 (2.3%) |

2,456 (1.7%) |

| Gestational Hypertension/ Preeclampsia |

35,981 (4.8%) |

2,993 (5.3%) |

1,167 (5.0%) |

410 (4.3%) |

4,820 (3.4%) |

All comparisons are statistically significant at p-value ≤0.001 for the X2 statistic corresponding to the 5 smoking group comparison for each maternal characteristic in this table.

Dichotomous variables are presented as percent of n for corresponding smoking group.

WIC - The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) provides Federal grants to States for supplemental foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-breastfeeding postpartum women, and to infants and children up to age five who are found to be at nutritional risk.

Smoking behaviors in the preconception period and also in the final 3 months of smoking are outlined in Table 2. Women who smoked throughout pregnancy were more likely to be considered a “heavy smoker” in the preconception period, smoking ≥20 cigarettes per day, than the women that quit early in pregnancy (57.4% vs 31.3%, respectively). All groups did significantly modify their behavior, with the majority of women reducing their use to <10 cigarettes per day.

Table 2.

Smoking Behaviors

| Never smokers N=748,055 |

Quit in the 1st trimester N=57,017 |

Quit by the 2nd trimester N=23,278 |

Quit by the 3rd trimester N=9,515 |

Smoked throughout pregnancy N=141,333 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preconception Smoking Behaviors | |||||

| Average Number of Cigarettes Smoked per Day |

0 | 11.8 ± 9.7 | 14.6 ± 10.4 | 16.2 ± 9.8 | 17.1 ± 9.9 |

| Smoke ≥ 1 ppd (≥20 cigs/day) |

0% | 17,822 (31.3%) |

10,280 (44.2%) |

5,035 (52.9%) |

81,072 (57.4%) |

| Pregnancy Smoking Behaviorsa | |||||

| Preconception | 1st Trimester | 2nd Trimester | 3rd Trimester | ||

| Average Number of Cigarettes Smoked per Day |

0 | 11.8 ± 9.7 | 9.0 ± 8.1 | 7.2 ± 7.2 | 10.0 ± 7.5 |

| < 10 | 0.0% | 22,209 (39.0%) |

12,613 (54.2%) |

6,285 (66.1%) |

60,797 (43.0%) |

| 10–19 | 0.0% | 16,986 (29.8%) |

6,304 (27.1%) |

2,137 (22.5%) |

52,594 (37.2%) |

| ≥ 20 | 0.0% | 17.822 (31.3%) |

4,361 (18.7%) |

1,093 (11.5%) |

27,942 (19.8%) |

All comparisons are statistically significant at p-value ≤0.001 for the X2 statistic corresponding to the 5 smoking group comparison for each maternal characteristic in this table.

Dichotomous variables are presented as percent of n for corresponding smoking group.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Each column represents the smoking behavior in the final 3 months of smoking

Quit in the 1st Trimester = ≥1 cig/day in the 3 months before pregnancy and 0 cig/day in the 1st, 2nd, & 3rd trimester

Quit by the 2nd Trimester = ≥1 cig/day in the 3 months before pregnancy & in the 1st trimester and 0 cig/day in the 2nd and 3rd trimester

Quit by the 3rd Trimester = ≥1 cig/day in the 3 months before pregnancy, 1st trimester, & 2nd trimester and 0 cig/day in the 3rd trimester

Smoked throughout pregnancy = ≥1 cig/day in all categories

Table 3 summarizes the unadjusted and adjusted relative risk for 1st trimester smoking cessation associated with each maternal characteristic. Of all smokers (N=231,143), nearly a quarter (N= 57,017; 24.7%) quit early in pregnancy. The patient characteristics most strongly associated with early smoking cessation included non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic ethnicity, having at least some college education, being multiparous, being married during pregnancy, and initiating breast feeding prior to discharge from the hospital. Several factors that are known to be associated with increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes were also found to be negatively associated with smoking cessation in pregnancy, such as low educational attainment, limited quantity of prenatal care, prior preterm birth, young maternal age (< 20 years), advanced maternal age (≥35 yrs), and indicators of low socioeconomic status (WIC and Medicaid recipients). Unsurprisingly, women who were the heaviest smokers (≥20 cigarettes per day) were the least likely to quit during pregnancy (Table 3). Notably, one of the modifiable pregnancy factors, early initiation of prenatal care, was associated with one of the highest increase in early smoking cessation, adj RR 1.52 (1.48, 1.57) even after accounting for confounding influences of other factors. Additionally, mothers who initiated breastfeeding prior to discharge from the hospital had 2.0 fold increase in early smoking cessation, both of which are positive health related choices that seem to cluster in the same mothers.

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Smoking Cessation in Pregnancy

| Women who quit smoking early in pregnancy (%)a |

Women who smoked throughout pregnancy (%)a |

Unadjusted RR of Quitting Early in Pregnancy 95% CI)b |

Adjusted RR‡ of Quitting Early in Pregnancy (95% CI)c |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All: | 57,017 (24.7%)d | 141,333 (61.1%)d | ||

| Education: | ||||

| Lower than high school diploma | 7,651 (3.3%) | 45,239 (19.6%) | 0.52 (0.51, 0.54) | 0.60 (0.58, 0.63) |

| High school graduate | 18,389 (8.0%) | 57,083 (24.7%) | Ref | Ref |

| Some college | 18,218 (7.9%) | 29,421 (12.7%) | 1.92 (1.88, 1.97) | 1.66 (1.61, 1.73) |

| College graduate or above | 12,578 (5.4%) | 9,015 (3.9%) | 4.33 (4.19, 4.47) | 2.29 (2.18, 2.40) |

| Mother's race: | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 47,384 (20.5%) | 121,297 (52.5%) | Ref | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 7,103 (3.1%) | 16,309 (7.1%) | 1.11 (1.08, 1.15) | 1.58 (1.51, 1.66) |

| Hispanic | 1,971 (0.9%) | 2,784 (1.2%) | 1.81 (1.71, 1.92) | 2.12 (1.95, 2.31) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 495 (0.2%) | 692 (0.3%) | 1.83 (1.63, 2.06) | 1.54 (1.28, 1.84) |

| Prenatal care: | ||||

| Limited prenatal care (≤5 visits) | 3,583 (1.6%) | 17,911 (7.7%) | 0.45 (0.43, 0.47) | 0.60 (0.57, 0.64) |

| First prenatal visit ≤12 weeks gestation | 34,163 (14.8%) | 65,956 (28.5%) | Ref | Ref |

| Late initiation of care (>20 weeks) | 2,903 (1.3%) | 12,883 (5.6%) | 0.43 (0.41, 0.45) | 0.56 (0.53, 0.58) |

| No prenatal care | 636 (0.3%) | 4,104 (1.8%) | 0.30 (0.27, 0.32) | 0.40 (0.36, 0.44) |

| Parity: | ||||

| Primiparous (first pregnancy) | 28,776 (12.4%) | 43,912 (19.0%) | Ref | Ref |

| Multiparous (2 or more births) | 27,293 (11.8%) | 95,245 (41.2%) | 2.29 (2.24, 2.33) | 2.30 (2.23, 2.37) |

| Previous pre-term birth: | ||||

| Yes | 1,689 (0.7%) | 7,527 (3.3%) | 0.54 (0.51, 0.57) | 0.82 (0.76, 0.88) |

| No | 54,569 (23.6%) | 130,912 (56.6%) | Ref | Ref |

| Mother's reported age: | ||||

| <20 | 6,508 (2.8%) | 17,804 (7.7%) | 0.89 (0.86, 0.92) | 0.88 (0.84, 0.93) |

| 20–34 | 46,794 (20.2%) | 113,906 (49.3%) | Ref | Ref |

| ≥35 | 3,715 (1.6%) | 9,623 (4.2%) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.98) | 0.75 (0.70, 0.79) |

| Marriage status: | ||||

| Married | 25,432 (11.0%) | 40,451 (17.5%) | 2.01 (1.97, 2.05) | 1.52 (1.47, 1.57) |

| Not married | 31,464 (13.6%) | 100,399 (43.4%) | Ref | Ref |

| WIC enrollment: | ||||

| Yes | 28,180 (12.2%) | 96,173 (41.6%) | 0.44 (0.43, 0.45) | 0.59 (0.57, 0.61) |

| No | 28,505 (12.3%) | 42,927 (18.6%) | Ref | Ref |

| Medicaid funded delivery: | ||||

| Yes | 25,180 (10.9%) | 96,713 (41.8%) | 0.35 (0.34, 0.36) | 0.56 (0.54, 0.57) |

| No | 31,464 (13.6%) | 39,725 (17.2%) | Ref | Ref |

| Twins: | ||||

| Yes | 1,915 (0.8%) | 3,645 (1.6%) | 1.31 (1.24, 1.39) | 1.50 (1.38, 1.64) |

| No | 55,047 (23.8%) | 137,635 (59.5%) | Ref | Ref |

| Initiation of breast feeding: | ||||

| Yes | 34,719 (15.0%) | 52,368 (22.7%) | 2.76 (2.70, 1.81) | 1.99 (1.94, 2.05) |

| No | 19,706 (8.5%) | 89,921 (38.9%) | Ref | Ref |

| Heavy smoker (≥20/day) before pregnancy: | ||||

| Yes | 17,822 (7.7%) | 81,072 (35.1%) | 0.34 (0.33, 0.35 | 0.35 (0.34, 0.36) |

| No | 39,195 (17.0%) | 60,261 (26.1%) | Ref | Ref |

| Mother’s prepregnancy BMI: | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 2,574 (1.1%) | 10,410 (4.5%) | 0.59 (0.56, 0.61) | 0.66 (0.61, 0.70) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 25,804 (11.2%) | 61,201 (26.5%) | Ref | Ref |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 13,448 (5.8%) | 30,563 (13.2%) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.07) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) |

| Obese (≥30) | 15,191 (6.6%) | 39,159 (16.9%) | 0.92 (0.90, 0.94) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) |

| Hypertension: | ||||

| None | 52,164 (22.6%) | 131,030 (56.7%) | Ref | Ref |

| Chronic hypertension | 1,049 (0.5%) | 2,456 (1.1%) | 1.07 (0.99, 1.15) | 1.01 (0.91, 1.12) |

| Gestational HTN/Preeclampsia | 2,993 (1.3%) | 4,820 (2.1%) | 1.55 (1.49, 1.63) | 1.33 (1.25, 1.43) |

| Diabetes: | ||||

| None | 52,416 (22.7%) | 130,151 (56.3%) | Ref | Ref |

| Pre-gestational | 442 (0.2%) | 1,301 (0.6%) | 0.84 (0.76, 0.94) | 0.83 (0.71, 0.97) |

| Gestational | 3,348 (1.4%) | 6,857 (3.0%) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | 1.08 (1.01, 1.15) |

Ref, reference category.

Dichotomous variables are presented as percent of all smokers who quit early in pregnancy

Each section in column 2 and 3 may not add up to the respective total # at the top of the respective column secondary to missing data

Unadjusted RR derived from simple logistic regression of each individual characteristic compared to the referent category for the corresponding variable in each cell.

Adjusted RR derived from one comprehensive multivariate logistic regression model including all characteristics in this table.

Percentage indicates the number out of all smokers, not entire cohort

CONCLUSION

This large population-based study provides a detailed assessment of patient characteristics, which are most strongly associated with early gestational smoking cessation in a contemporary cohort of over 1 million pregnant women living in a state with a rate of smoking in pregnancy that is twice the national average, an area with an urgent need to focus smoking cessation interventions. We found that women with known risk factors for poor perinatal outcomes are unfortunately those who are the least likely to stop smoking early in pregnancy. More importantly, we found an important potentially modifiable intervention, early initiation of prenatal care, was associated with a significantly increased likelihood of smoking cessation in pregnancy. We also found that women who initiated breast feeding prior to hospital discharge had an increased likelihood of early smoking cessation, both of which are positive health behaviors and would often be seen to occur together in women who are motivated to have the best outcomes for their child.

Similar to previously published studies, we identified low educational attainment, young maternal age, white race, unmarried, and low SES status as consistent factors that negatively influenced smoking cessation in pregnancy.13–15 However, we additionally studied the influence of a breadth of other pregnancy related factors that, like smoking, are associated with poorer perinatal outcomes, such as pre-pregnancy medical complications and obesity. Our study is unique in that it is the largest of these comparable studies with n=198,350 (57,017 who quit in the first trimester and 141,333 who smoked through pregnancy) compared to sample size of 902 to 5288 in the previously published studies. We utilized a population-based sample rather than a selected sample of voluntary study participants, which likely results in better generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, we analyzed the influence of patient behavioral factors such as timing of initiation of prenatal care that could be considered as target interventions for pregnancy smoking cessation programs.

There is theoretic and biologic plausibility in the negatively associated factors in this study. It is reasonable to anticipate that women who have a lower educational level, those who are young (<20 years old) and those with lower SES status indicated by WIC and Medicaid enrollment would be less likely to access the resources or appropriate support to assist in smoking cessation. Those women who were heavy smokers prior to pregnancy are less likely to quit smoking secondary to their strong nicotine dependence; however, they are the most likely to incur pregnancy complications and most likely to benefit from target interventions for early smoking cessation.

Early prenatal care, black race and Hispanic ethnicity, marriage, and initiation of breastfeeding prior to discharge all contribute to the factors associated with a greater likelihood of smoking cessation. Black and Hispanic women have a better success rate with smoking cessation in pregnancy, perhaps related to cultural teaching Education on the importance of smoking cessation by a physician and the potential protection of a family member (fetus) are strong motivators for behavioral changes in tobacco use. Black women have more success with smoking cessation interventions than white women, which may also partly explain the racial differences observed in smoking cession in our study.16 We also found that women who ultimately breastfeed after birth are also more likely to have successfully quit smoking during pregnancy. These similar positive health behaviors may reflect a more educated group of women who are motivated by the well-being of their infant or are at least more able to successfully implement fetal-newborn beneficial behaviors.

For the pregnancies in which cessation occurred in this cohort, it is unclear whether medical or social interventions were utilized because birth certificate data source does not report such information. We suggest that obstetric providers determine the patient’s willingness to quit by using the 5 A’s (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) of smoking cessation as early as the first prenatal visit.17 There are many smoking cessation programs available for pregnant women.18 Repeat education, counseling, and support at each prenatal visit is of the utmost importance as well. Unfortunately, at this time pharmacotherapy during pregnancy has not been sufficiently evaluated for its safety or efficacy during pregnancy and lactation and thus, is not readily recommended.17

One of the strengths of this study is that, to our knowledge, this is the largest study performed in the United States. Its population-based contemporary basis makes it generalizable to most pregnancies cared for currently in our country. Our study does have limitations, however. Our data was obtained from birth certificates, which are not designed for research purposes. Information about concomitant alcohol use, drug use, and second hand smoke exposure was not available in our data set, and thus could not be adjusted for in our analysis. Some studies have reported that tobacco use may be underreported, which may misclassify some smokers into the reference group in this study resulting in an underestimate of our effect size estimates.19–20 Data on smoking in pregnancy is self-reported on the birth certificate, which may also have the issue with underreporting; however, self-report of reproductive smoking behaviors have been shown to be quite reliable.21 Some covariates analyzed were limited by missing data, such as early initiation of prenatal care ≤12 weeks, which was available in 74.6% of births studied. Likewise, some additional covariates such as medical complications may also be underreported, further biasing our effect – estimates toward the null.22 However, other than the issue of underestimating the influence of some characteristics on smoking cessation, we believe this study provides the most comprehensive current account of influences on pregnancy smoking cessation available to date.

In summary, this study identifies targeted groups of women who are both more and less successful at smoking cessation early in pregnancy. Since early prenatal care (≤12 weeks gestation) greatly increases smoking cessation by 52%, public health initiatives and interventions should focus on the importance of early access to prenatal care for these particularly vulnerable groups of women who are at inherently high risk of pregnancy complications. Continued discussions of the importance of early smoking cessation should occur at each prenatal visit, as it is unquestionably beneficial for pregnancy outcomes.

Acknowledgments

All of the analysis, interpretations, and conclusions that were derived from the data source and included in this article are those of the authors and not the Ohio Department of Health. Access to de-identified Ohio birth certificate data was provided by the Ohio Department of Health.

Financial Support: Ms. Blatt received research funding from an educational grant from the University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Women’s Health Scholars Program. Dr. DeFranco received research funding from the Perinatal Institute, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati Ohio; March of Dimes Grant 22-FY14-470

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This study includes data provided by the Ohio Department of Health which should not be considered an endorsement of this study or its conclusions.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCormick MC, Brooks-Gunn J, Shorter T, Holmes JH, Wallace CY, Heagarty MC. Factors associated with smoking in low-income pregnant women: Relationship to birth weight, stressful life events, social support, health behaviors and mental distress. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(5):441–448. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah NR, Bracken MB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies on the association between maternal cigarette smoking and preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 182(2):465–472. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70240-7. 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiFranza JR, Lew RA. Effect of maternal cigarette smoking on pregnancy complications and sudden infant death syndrome. J Fam Pract. 1995;40(4):385–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castles A, Adams EK, Melvin CL, Kelsch C, Boulton ML. Effects of smoking during pregnancy: Five meta-analyses. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16(3):208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollack HA. Sudden infant death syndrome, maternal smoking during pregnancy, and the cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation intervention. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(3):432–436. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mund M, Louwen F, Klingelhoefer D, Gerber A. Smoking and Pregnancy-A Review on the first major environmental risk factor of the unborn. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013;10:6485–6499. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10126485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietz PM, England LJ, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Tong VT, Farr SL, Callaghan WM. Infant morbidity and mortality attributable to prenatal smoking in the U.S. Am J. Prev Med. 2010;39:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People. Washington, DC: 2020. [Accessed 12/1/14]. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available at https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search/Search-the-Data?nid=5364. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osterman MJ, Martin JA, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ, Wilson EC, Kirmeyer S. Newly released data from the revised U.S. birth certificate, 2011. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2013 Dec 10;62(4):1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blatt K, Moore E, Chen A, Van Hook J, DeFranco E. Association of reported trimester-specific smoking cessation with fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1452–1459. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Center for Health Statistics. Guide to completing the facility worksheets for the certificate of live birth and report of fetal death (2003 revision) Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Accessed 12/1/14]. Retrieved July 2014 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Vital Statistics System2003 Revisions of the U.S. Standard Certificates of Live Birth and Death and the Fetal Death Report Accessed 2/11/14Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/birth11-03final-acc.pdf

- 13.Yu SM, Park CH, Schwalberg RH. Factors associated with smoking cessation among U.S. pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 2002;6(2):89–97. doi: 10.1023/a:1015412223670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masho SW, Bishop DL, Keyser-Marcus L, Varner SB, White S, Svikis D. Least explored factors associated with prenatal smoking. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(7):1167–1174. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1103-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilman SE, Breslau J, Subramanian SV, et al. Social factors, psychopathology, and maternal smoking during pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:448–453. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Windsor RA, Lowe JB, Perkins LL, Smith-Yoder D, Artz L, Crawford M, Amburgy K, Boyd NR., Jr Health education for pregnant smokers: its behavior impact and cost benefit. American Journal of Public Health. 1993b;83(2):201–206. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smoking cessation during pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 471. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1241–1244. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182004fcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smoking cessation for pregnancy and beyond: a virtual clinic. [Accessed April 30, 2015]; Available at: https://www.smokingcessationandpregnancy.org/resources. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reichman NE, Schwartz-Soicher O. Accuracy of birth certificate data by risk factors and outcomes: analysis of data from New Jersey. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:32.e1–32.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costakos DT, Love LA, Kirby RS. The computerized perinatal database: are the data reliable? Am J Perinatol. 1998;15:453–459. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickett KE, Rathouz PJ, Kasza K, Wakschlag LS, Wright R. Self-reported smoking, cotinine levels, and patterns of smoking in pregnancy. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2005 Sep;19(5):368–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reichman NE, Schwartz-Soicher O. Accuracy of birth certificate data by risk factors and outcomes: analysis of data from New Jersey. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007 Jul;197(1):32 e31–32 e38. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]