Abstract

Background

Understanding the potential psychosocial mechanisms that explain (i.e., mediate) the associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems can improve interventions targeting college students.

Objectives

The current research examined four distinct facets of rumination (e.g., problem-focused thoughts, counterfactual thinking, repetitive thoughts, and anticipatory thoughts) and drinking to cope motives as potential explanatory mechanisms by which depressive symptoms are associated with increased alcohol-related problems.

Method

Participants were undergraduate students from a large, southeastern university in the United States that consumed at least one drink per typical week in the previous month (n = 403). The majority of participants were female (n = 291; 72.2%), identified as being either White, non-Hispanic (n = 210; 52.1%), or African-American (n = 110; 27.3%), and reported a mean age of 21.92 (SD = 5.75) years.

Results

Structural equation modeling was conducted examining the concurrent associations between depressive symptoms, rumination facets, drinking to cope motives, and alcohol-related problems (i.e., cross-sectional). There was one significant double-mediated association that suggested that increased depressive symptoms is associated with increased problem-focused thoughts, which is associated with higher drinking to cope motives and alcohol-related problems.

Conclusions/Importance

Our results suggests that problem-focused thoughts at least partially explains the associations between depression and maladaptive coping (i.e., drinking to cope), which in turn is related to problematic drinking among college students. Limitations and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: Alcohol-related Problems, Drinking to cope, Rumination, Depressive Symptoms, College Students

Heavy drinking among college students has been recognized as a major public health concern that has remained a consistent problem over the past two decades (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). In fact, The National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA, 2015) has recognized alcohol misuse as the most important health hazard for college students because of the high rates of heavy drinking, negative alcohol-related consequences, and prevalence of alcohol use disorders. Specifically, alcohol-related problems are highly prevalent among college students and range from academic consequences to injuries and death (Hingson et al., 2009; Perkins, 2002).

In addition to alcohol misuse, researchers have found surprisingly high rates of psychological distress, particularly depression among college students (Bayram & Bilgel, 2008; Eisenberg, Gollust, Golberstein, & Hefner, 2007). Lending support to self-medication models of alcohol use (Conger, 1951, 1956; Khantzian, 1999), depression has been shown to be positively related to alcohol-related outcomes in the college student population, especially alcohol-related problems (Armeli, Conner, Cullum, & Tennen, 2010; Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011; Weitzman, 2004). To better inform and tailor prevention and treatment efforts among college students, it is important to understand the potential psychosocial mechanisms that explain (i.e., mediate) the associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems.

Drinking to Cope Motives

Motivational models of alcohol (Cooper, 1994; Cox & Klinger, 1988, 1990) posit that drinking motives, or the reasons for drinking, are the most proximal antecedents to the decision to drink. Coping motives, or drinking to cope, is defined as consuming alcohol to ameliorate negative affect and has been shown to be directly related to experiencing alcohol-related problems controlling for the amount of consumption (Ham & Hope, 2003; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005). Models of Social Learning Theory (Abrams & Niaura, 1987; Bandura, 1977) posit that individuals engage in drinking to cope because they expect that drinking alcohol provides immediate coping benefits by alleviating their negative affect (e.g., depression). In other words, individuals expect alcohol to have positive and/or coping benefits and thus they consume alcohol as a coping mechanism. Based on these models of drinking, one may assert that drinking to cope motivation may be one mechanism through which depressive symptoms are associated with an increase in alcohol-related problems among college students.

Both cross-sectional (Gonzalez, Reynolds, & Skewes, 2011) and longitudinal findings (Kenney, Jones, & Barnett, 2015) suggest that drinking to cope motives are one mechanism through which depressive symptoms is associated with increased alcohol-related problems among college students. For example, Kenney, Jones, and Barnett (2015) found that for women, higher pre-college depressive symptoms predicted higher drinking to cope during college, which in turn was associated with more alcohol-related problems during college. As detailed above, research provides support for how depressive symptoms relate to alcohol-related problems among college students through drinking to cope motives. However, there has been a paucity of research examining why individuals engage in drinking to cope when dealing with stressors (i.e., depressive symptoms) and how this may lead to increased alcohol-related problems. Further, it might be that other psychosocial factors are mechanisms of change through which depressive symptoms leads to more drinking to cope motives and alcohol-related problems.

Rumination

Response Styles Theory posits that rumination: 1) enhances negative thinking, 2) impairs problem solving, 3) interferes with instrumental behavior (i.e., reducing motivation to engage in alleviating behaviors), and 4) erodes social support (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubormisky, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Moreover, rumination has been shown to be a robust risk factor for alcohol use and misuse (Ciesla, Dickson, Anderson, & Neal, 2011; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema & Harrell, 2002; Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007). For example, Ciesla, Dickson, Anderson, & Neal (2011) found that various facets of negative repetitive thought (e.g., angry rumination) differentially relate to increased alcohol consumption and binge drinking among college students. Specifically, they found that angry rumination (even when controlling for hostility affect) was associated with greater weekly drinking. Based on these findings Ciesla and colleagues (2011) concluded, “It is possible that individuals may drink in order to interrupt the repetitive, obsessive thoughts which exacerbate and prolong negative moods, rather than simply drinking due to the affective state itself” (pg. 149). Thus, although research indicates that depressive symptoms are related to an increased motivation to use alcohol as a coping mechanism (Gonzalez, et al., 2011; Kenney, Jones, & Barnett, 2015), it is possible that this is mediated by elevations in ruminative thinking. However, at present, we are unaware of any research that has examined these constructs in a double-mediation model among college students (i.e., depressive symptoms → rumination → drinking to cope → alcohol-related problems). By confirming this model, we gain a more keen understanding of just how depressive symptoms can lead to increased consequences beyond a simple increase in consumption and drinking to cope motivation. Specifically, we predict that increased depression is associated with increased ruminative thinking. In turn, increased ruminative thinking is related to increased drinking to cope motives, which confers the increased risk of experiencing alcohol-related problems.

Further, although most research examining rumination and alcohol-related outcomes have examined rumination as a unidimensional construct (Nolen-Hoeksema & Harrell, 2002; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008), recent research has indicated that rumination may be a multi-dimensional construct (see Smith & Alloy, 2009 for a review) with various facets relating to different psychological outcomes (Armey et al., 2009; Taku, Cann, Tedeschi, & Calhoun, 2009), coping styles (Burwell & Shirk, 2007; Marroquin, Fontes, Scilletta, & Miranda, 2010), and alcohol consumption (Ciesla et al., 2011).

For example, recent factor analytic work (Tanner, Voon, Hasking, & Martin, 2013) suggests that the Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire (RTSQ; Brinker & Dozois, 2009) assesses four distinct subcomponents of rumination: problem-focused thoughts, counterfactual thinking, repetitive thoughts, and anticipatory thoughts. According to Tanner and colleagues (2013), problem-focused thoughts were defined as recurrent thoughts about solving problems (e.g., consistent thinking of causes, consequences, and symptoms of negative affect); counterfactual thinking refers to thoughts about alternative outcomes; repetitive thoughts were defined as repetitive and involuntary thoughts (e.g., persistent reflection on negative affect); and anticipatory thoughts were defined as intrusive thoughts over future possible events (i.e., future-orientated rumination). Interestingly, Tanner et al. found that problem-focused thoughts and repetitive thoughts predicted higher psychological distress and non-productive coping, whereas counterfactual thinking only predicted higher non-productive coping. Finally, anticipatory thoughts was found to be adaptive (i.e., negatively associated) against psychological distress and non-productive coping. A more recent study shows that these facets of rumination are differentially associated with psychological outcomes, specifically major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (Roley, Claycomb, Contractor, Dranger, Armour, & Elhai, 2015).

Purpose of Study

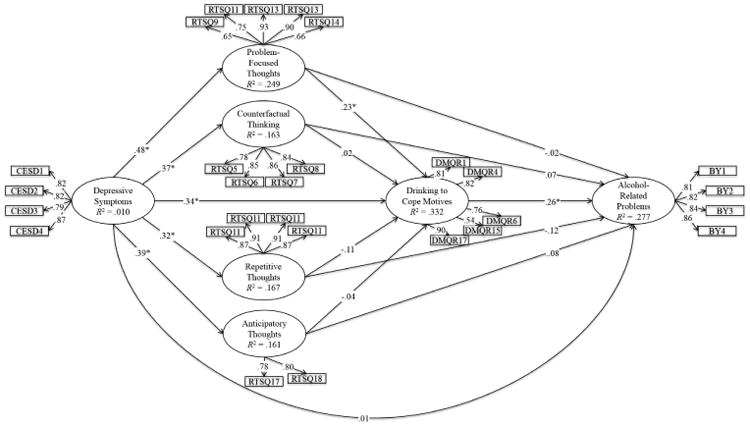

The purpose of the present study is to examine the newly proposed subcomponents of rumination (e.g., problem-focused thoughts, counterfactual thinking, repetitive thoughts, and anticipatory thoughts) and drinking to cope motives as potential double mediators of the association between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems among college students (see Figure 1). This examination will provide a better understanding of the specific aspects of rumination that may lead to alcohol misuse and consequences. Based on models of depression (Response Styles Theory; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) and drinking motives (Cooper, 1994), we expected that the associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems would be mediated by rumination and drinking to cope motives, such that higher depressive symptoms would relate to higher rumination. In turn, higher rumination would be related to higher drinking to cope motives, which would relate to higher alcohol-related problems. However, given the scarcity of research examining rumination multidimensionally, we did not have hypotheses regarding which specific facet would be related to drinking to cope, and therefore be potential mediators of the associations between depressive symptoms, drinking to cope motives, and alcohol-related problems.

Figure 1.

Proposed Structural Equation Model for the associations between depressive symptoms, rumination subcomponents (e.g., problem-focused thoughts, counterfactual thinking, repetitive thoughts, and anticipatory thought), drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were undergraduate students recruited from a Psychology Department participant pool at a large, southeastern university in the United States to participate in an online survey. Data were collected in the Fall/Spring semester of 2014. Although 776 students were recruited, 373 non-drinkers were excluded from analyses (i.e., defined as drinking 0 drinks per typical week in the previous month), leaving an analytic sample of 403 college student drinkers. Among college student drinkers, the majority of participants identified as being either White, non-Hispanic (n = 210; 52.1%), or African-American (n = 110; 27.3%), were female (n = 291; 72.2%), and reported a mean age of 21.92 (SD = 5.75) years. See Table 1 for a full description. At the participating institution, participants completed an online survey regarding personal mental health, coping strategies, and alcohol use behaviors. To be eligible, participants must have been currently enrolled in any psychology course and been at least 18 years old. Participants received research credit for completing the study which may be applied as extra credit for courses at the participating university. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the participating institution.

Table 1. Demographics.

| Gender | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 112 (27.8) |

| Female | 291 (72.2) |

|

| |

| Age | n (%) |

|

| |

| M | 21.92 (5.75) |

| 18 | 79 (19.6) |

| 19 | 82 (20.3) |

| 20 | 59 (14.6) |

| 21 | 54 (13.4) |

| 22 | 36 (8.9) |

| 23+ | 87 (21.8) |

| Missing | 6 (1.4) |

|

| |

| Race/Ethnicity | n (%) |

|

| |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4 (1.0) |

| Asian | 13 (3.2) |

| Black/African American | 110 (27.3) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 2 (0.5) |

| White, non-Hispanic | White | 210 (52.1) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 14 (3.5) |

| Mixed | 38 (9.4) |

| Other | 7 (1.7) |

| Missing | 5 (1.2) |

|

| |

| Class Standing | n (%) |

|

| |

| Freshman | 115 (28.5) |

| Sophomore | 87 (21.6) |

| Junior | 95 (23.6) |

| Senior | 102 (25.3) |

| Grad Student | 2 (0.5) |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) |

|

| |

| Marital Status | n (%) |

|

| |

| Never married | 349 (86.6) |

| Married | 32 (7.9) |

| Separated | 3 (0.7) |

| Divorced | 15 (3.7) |

| Widowed | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 3 (0.7) |

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale-Revised (CESD-R; Van Dam & Earleywine, 2011). The CESD-R assesses participants' depressive symptoms that closely reflect the DSM-5 criteria for depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The CESD-R is a self-report measure that consist of 20 items and uses a 5-point response scale (1 = Not at all or Less than 1 day, 2 = 1-2 Days, 3 = 3-4 Days, 4 = 5-7 Days, 5 = Nearly Every day for 2 weeks). As advised by Van Dam and Earlywine (2011), ‘5-7 days’ and ‘nearly every day…’ were collapsed into the same value in order to make the CESD-R have the same scoring range (i.e., 0-60) as the original CESD (Eaton et al., 2004). The participants were provided with instructions stating, “Below is a list of the ways you might have felt or behaved. Please tell me how often you have felt this way during the past week”. Example items were, “I felt sad,” and “I felt depressed”. An examination of the psychometric properties of the measure revealed that the CESD-R exhibited good psychometric properties and is an accurate and valid measure of depression (Van Dam & Earleywine, 2011). Reliability for the current study was excellent (α = .91) and similar in strength to the alpha reported by Van Dam and Earleywine (α = .93).

Rumination

Rumination was assessed using the Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire (RTSQ; Brinker & Dozois, 2009). The measure assesses participant's overall tendency toward ruminative thinking. The RTSQ is a self-report measure that consist of 20 items and uses a 7-point response scale (1 = Not at all, 7 = Very Well). The participants were provided with instructions stating, “For each of the items below, please rate how well the item describes you.” Although an initial examination suggested a single factor structure, a more recent examination of the factor structure of the measure (Tanner et al., 2013) revealed four rumination subcomponents with good to excellent reliability: problem-focused thoughts (5 items; α = .89), counterfactual thinking (4 items; α = .87), repetitive thoughts (4 items; α = .89), and anticipatory thoughts (2 items; α = .71). Example items were: “I have never been able to distract myself from unwanted thoughts” (problem-focused thoughts); “I find myself daydreaming about things I wish I had done” (counterfactual thinking), “I find that my mind often goes over things again and again” (repetitive thoughts), and “When I am looking forward to an exciting event, thoughts of it interfere with what I am working on” (anticipatory thoughts). An initial examination of the psychometric properties of the measure revealed that the RTSQ exhibited good psychometric properties and is an accurate and valid measure of rumination (Brinker & Dozois, 2011). Reliability for the current study was similar in strength to the alphas reported by Tanner and colleagues and ranged from good to excellent: problem-focused thoughts (α = .88), counterfactual thinking (α = .90), repetitive thoughts (α = .94), and anticipatory thoughts (α = .77).

Drinking to Cope Motives

Motives for drinking were assessed using the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994). The measure assesses reasons for drinking within four domains: social, conformity, enhancement and coping. The DMQ-R is a self-report measure that consist of 20 items and uses a 5-point response scale (1 = never/almost never, 5 = almost always/always). However, for purposes of this study, only the coping subscale (5 items) was used1. The participants were provided with instructions stating, “Now I am going to read a list of reasons people sometimes give for drinking alcohol. Thinking of all the times you drink, how often would you say that you drink for each of the following reasons”. Example items for the drinking to cope subscale were, “to cheer up when you are in a bad mood” and “to forget your worries”. An examination of the psychometric properties of the measure revealed that the DMQ-R exhibited good psychometric properties and is an accurate and valid measure of drinking motives (Kuntsche, Stewart, & Cooper, 2008). Reliability for drinking to cope subscale within the current study was good (α = .87) and similar in strength to the alpha reported by Kuntsche and colleagues (α = .86).

Alcohol-related problems

Alcohol-related problems were assessed using Brief-Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (B-YAACQ; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005). The B-YAACQ assesses negative alcohol consequences over the past 30 days among college students. The B-YAACQ is a self-report measure that consist of 24 items and participants were presented with a checklist form of the scale where they checked a box for each problem that they experienced in the past month. Each item was scored dichotomously to reflect presence/absence of the alcohol-related problem (0 = no, 1 = yes). Example items include, “I have spent too much time drinking”, “While drinking, I have said or done embarrassing things”, and “I have felt badly about myself because of my drinking”. The 30-day version of the B-YAACQ has excellent reliability with internal consistency of the B-YAACQ was high at baseline (alpha = .84) and 6 weeks (alpha = .89), with no items detracting from Cronbach's alpha (Kahler, Hustad, Barnett, Strong, & Borsari, 2008). Reliability for the current study was excellent (α = .89) and similar in strength to the alphas reported by Kahler and colleagues (2008).

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was measured with a modified version of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Park, Marlatt, 1985). Participants were provided a 7-day grid from Monday to Sunday to indicate how much they drink during a typical week in the past 30 days. We summed number of standard drinks consumed on each day of the typical drinking week. For the present study, participant's number of drinks per typical week of drinking (M = 8.34, SD = 8.86) was used to control for alcohol consumption in all analyses.

Demographics

Demographic information for the participants was collected through a simple demographic questionnaire created by the research team. The participants gave information about their age, race, ethnicity, gender, class standing, and marital status. The questionnaire was administered at the end of the survey to reduce any potential bias.

Statistical Analysis

To test the proposed model (see Figure 1), structural equation modeling using Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012) was conducted. As shown in Figure 1, we proposed a structural model in which depressive symptoms was examined as a statistical predictor of the four subcomponents of rumination (e.g., problem-focused thoughts, counterfactual thinking, repetitive thoughts, and anticipatory thoughts), drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems. Further, the four rumination subcomponents were then modeled as predictors of drinking to cope and alcohol-related problems. Last, drinking to cope was modeled as a predictor of alcohol-related problems. Thus, a double-mediated path was examined for each subcomponent of rumination (e.g., depressive symptoms→problem-focused thoughts→drinking to cope→alcohol-related problems). Covariates (gender and alcohol use) were modeled as predictors of all other variables in the model.

To evaluate overall model fit, we used model fit criteria suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > .95, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > .95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < .06, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < .08. To reduce the complexity of the model, we followed the item-to-construct balance approach described by Little, Cunningham, Shahar, and Widaman (2002) by creating parcels for depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems. We first confirmed and then extracted a single factor in exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) for each latent construct, sorted the items from highest to lowest factor loadings, and created four balanced parcels by pairing items with the highest factor loadings with items with the lowest factor loadings. A supplementary table of the correlations among the parcels and items used as indicators of the latent factors in the model are available from the authors upon request.

We examined the total, direct, and indirect effects of each predictor variable on outcomes using bias-corrected bootstrapped estimates (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993) based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples, which provides a powerful test of mediation (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007) and is robust to small departures from normality (Erceg-Hurn & Mirosevich, 2008). Parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation, and missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood, which is more efficient and has less bias than alternative procedures (Enders, 2001; Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Statistical significance was determined by 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals that do not contain zero.

Results

After item parceling, the SEM model (Figure 2) provided an excellent fit to the data based on CFI = .953, TLI = .945, RMSEA = .050 (90% CI [.045, .055]), SRMR = .049. The significant Model χ2(371) = 747.164, p < .001 would suggest poor model fit; however, the Model χ2 is highly sensitive to sample size (Kline, 1998; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993).

Figure 2.

Depicts the estimated structural equation model (n = 403). *p < .05. Female gender (-5 = men, .5 = women) was significantly positively related to problem-focused thoughts (β = .12), counter-factual thinking (β = .15), and repetitive thoughts (β = .24). However, gender was not significantly related to depressive symptoms (β = .04), anticipatory thoughts (β = .10), drinking to cope (β = -.04), and alcohol-related problems (β = .08). Alcohol use was positively related to drinking to cope (β = .32) and alcohol-related problems (β = .36). However, alcohol use was not significantly related to depressive symptoms (β = .10), problem-focused thoughts (β = .03), counter-factual thinking (β = .01), repetitive thoughts (β = .00), and anticipatory thoughts (β = .01). These paths are not shown in the figure for reasons of parsimony.

Bivariate Relationships

All zero-order correlations are summarized in Table 2. Depressive symptoms had a moderate positive correlation with each subcomponent of rumination (e.g., problem-focused thoughts, counterfactual thinking, repetitive thoughts, and anticipatory thoughts) and drinking to cope motives. Depressive symptoms also had a weak positive correlation with alcohol-related problems, but was unrelated to alcohol consumption. As expected, all of the rumination subcomponents were strongly positively correlated with each other, but only three of the four rumination components were related to drinking to cope motives. Specifically, problem-focused thoughts had a moderate positive correlation, and counter-factual thinking and anticipatory thought had weak positive correlations. Further, problem-focused thoughts and counterfactual thinking had weak positive correlations with alcohol-related problems; the other two subcomponents were not significantly correlated with alcohol-related problems. None of the rumination subcomponents were significantly correlated with alcohol use, but all of them except anticipatory thoughts were correlated with gender, indicating that women had higher scores on these facets of rumination. Finally, drinking to cope motives had a moderate positive relationship with alcohol-related problems and alcohol use.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations among primary latent variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depressive Symptoms | 15.23 | 11.00 | ||||||||

| 2. Problem-focused Thoughts | .457 | 18.43 | 6.91 | |||||||

| 3. Counterfactual Thinking | .325 | .585 | 19.58 | 5.76 | ||||||

| 4. Repetitive Thoughts | .316 | .588 | .723 | 19.99 | 5.76 | |||||

| 5. Anticipatory Thoughts | .322 | .566 | .571 | .556 | 9.19 | 2.84 | ||||

| 6. Drinking to Cope | .395 | .320 | .184 | .110 | .178 | 9.95 | 4.86 | |||

| 7. Alcohol-related Problems | .141 | .122 | .105 | .016 | .094 | .390 | 5.28 | 4.96 | ||

| 8. Alcohol Use | .080 | .042 | .007 | -.019 | .018 | .361 | .430 | 8.34 | 8.86 | |

| 9. Gender | .011 | .129 | .135 | .225 | .094 | -.092 | -.033 | -.215 | 0.22 | 0.45 |

Note. Gender was coded -.5 = men, .5 = women. Significant correlations (p < .05) are bolded for emphasis.

Direct effects

Significant direct effects are shown in Figure 2. Depressive symptoms were moderately associated with higher levels of each subcomponent of rumination: problem-focused thoughts, β = .48, 95% CI [.40, .57], counterfactual thinking, β = .37, 95% CI [.28, .46], repetitive thoughts, β = .32, 95% CI [.23, .42], and anticipatory thoughts, β = .39, 95% CI [.28, .49]. Furthermore, depressive symptoms was moderately associated with higher levels of drinking to cope motives, β = .34, 95% CI [.21, .47]. With regards to the subcomponents of rumination, only problem-focused thoughts was significantly positively associated with higher levels of drinking to cope motives, β = .23, 95% CI [.09, .38], after controlling for all other rumination subcomponents. Finally, drinking to cope motivation was positively associated with higher levels of alcohol-related problems, β = .26, 95% CI [.12, .41].

Indirect effects

The total, total indirect, specific indirect, and direct effects are summarized in Tables 3 and 4, where Table 3 reports the effects for the prediction of drinking to cope motives and Table 4 reports the effects for the prediction of alcohol consequences. Problem-focused thoughts significantly mediated the associations between depressive symptoms and drinking to cope motivation, indirect β = .11, 95% CI [.04, .18] accounting for 27.69% of the total effect of depressive symptoms on drinking to cope. However, no other rumination subcomponent significantly mediated the associations between depressive symptoms and drinking to cope motives or depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems (see Tables 3-4).

Table 3. Summary of total, indirect, and direct effects of depressive symptoms on drinking to cope.

| Outcome Variable: | Drinking to Cope | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Predictor Variable: Depressive Symptoms | β | 95% CI |

| Total | .409 | .302, .515 |

| Total indirecta | .070 | .008, .132 |

| Problem-focused Thoughts | .112 | .041, .183 |

| Counter-factual Thinking | .009 | -.054, .071 |

| Repetitive Thoughts | -.036 | -.089, .017 |

| Anticipatory Thoughts | -.016 | -.085, .054 |

| Direct | .339 | .209, .468 |

Note. Significant effects are in bold typeface for emphasis and were determined by a 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval (based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples) that does not contain zero.

Reflects the combined indirect effects via problem-focused thoughts, counter-factual thoughts, repetitive thoughts, anticipatory thoughts.

Table 4. Summary of total, indirect, and direct effects of depressive symptoms and rumination subcomponents on alcohol-related problems.

| Outcome Variable: | Alcohol-Related Problems | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Predictor Variable: Depressive Symptoms | β | 95% CI |

| Total | .126 | .016, .237 |

| Total indirecta | .117 | .027, .208 |

| Problem-focused Thoughts | -.009 | -.079, .062 |

| Counter-factual Thinking | .025 | -.043, .093 |

| Repetitive Thoughts | -.037 | -.092, .017 |

| Anticipatory Thoughts | .031 | -.056, .118 |

| Drinking to Cope | .088 | .029, .148 |

| Problem-focused Thoughts-Drinking to Cope | .029 | .003, .056 |

| Counter-factual Thinking-Drinking to Cope | .002 | -.015, .019 |

| Repetitive Thoughts-Drinking to Cope | -.009 | -.025, .007 |

| Anticipatory Thoughts-Drinking to Cope | -.004 | -.023, .015 |

| Direct | .009 | -.136, .154 |

|

| ||

| Predictor Variable: Problem-Focused Thoughts | β | 95% CI |

|

| ||

| Total | .043 | -.112, .197 |

| Total indirect (Drinking to Cope) | .061 | .007, .115 |

| Direct | -.018 | -.164, .127 |

|

| ||

| Predictor Variable: Counter-Factual Thinking | β | 95% CI |

|

| ||

| Total | .074 | -.115, .263 |

| Total indirect (Drinking to Cope) | .006 | -.039, .051 |

| Direct | .068 | -.113, .248 |

|

| ||

| Predictor Variable: Repetitive Thoughts | β | 95% CI |

|

| ||

| Total | -.143 | -.316, .029 |

| Total indirect (Drinking to Cope) | -.029 | -.076, .019 |

| Direct | -.115 | -.277, .047 |

|

| ||

| Predictor Variable: Anticipatory Thoughts | β | 95% CI |

|

| ||

| Total | .071 | -.158, .299 |

| Total indirect (Drinking to Cope) | -.011 | -.058, .037 |

| Direct | .081 | -.138, .300 |

Note. Significant effects are in bold typeface for emphasis and were determined by a 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval (based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples) that does not contain zero.

Reflects the combined indirect effects via problem-focused thoughts, counter-factual thoughts, repetitive thoughts, anticipatory thoughts, drinking to cope, problem-focused thoughts via drinking to cope, counter-factual thoughts via drinking to cope, repetitive thoughts via drinking to cope, and anticipatory thoughts via drinking to cope.

With regards to drinking to cope motives as a mediator, drinking to cope fully mediated the relationship between problem-focused thoughts and alcohol-related problems, indirect β = .06, 95% CI [.01, .12]. Drinking to cope motivation also mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems, indirect β = .09, 95% CI [.03, .15] accounting for 69.81% of the total effect of depressive symptoms on alcohol-related problems. Only one of the double-mediated effects was significant (i.e., depressive symptoms → problem-focused thoughts → drinking to cope → alcohol-related problems), indirect β = .03, 95% CI [.003, .056] accounting for 22.64% of the total effect of depressive symptoms on alcohol-related problems.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine potential mediators of the associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems. Based on models of depression (e.g., Response Styles Theory; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) and drinking (e.g., motivational models of alcohol use, Cooper, 1994), the present study tested a double-mediation model to examine whether newly proposed subcomponents of rumination (e.g., problem-focused thoughts, counterfactual thinking, repetitive thoughts, and anticipatory thoughts) mediated the associations between depressive symptoms and drinking to cope motives, in turn resulting in higher alcohol-related problems. Our results were partially consistent with our hypotheses, such that we found that the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems was uniquely explained by problem-focused thoughts and drinking to cope motives.

In support of Social Learning Theory (Abrams & Niaura, 1987; Bandura, 1977) and drinking motivational models of alcohol use (Cooper, 1994), depressive symptoms was associated with higher reports of drinking to cope and drinking to cope motives was associated with higher reports of alcohol-related problems, even when controlling for alcohol use. Although these findings are consistent with previous research (Gonzalez et al., 2011; Kenney et al., 2015); the present study found preliminary support for examining other mechanisms of change through which depressive symptoms leads to more drinking to cope motives and alcohol-related problems. Specifically, and in partial support of Response Styles Theory (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), we found that problem-focused thoughts uniquely mediated the positive associations between depressive symptoms and drinking to cope motives, which in turn was related to increased alcohol-related problems. In other words, once we controlled for gender, alcohol consumption, and the other rumination facets, the association between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems was still explained via problem-focused thoughts and drinking to cope motives.

Not only do our results offer support for examining ruminative thinking as a mediator between depressive symptoms and motivation to use alcohol as a coping mechanism, but they also demonstrate the value of distinguishing between distinct subcomponents of rumination (Ciesla et al., 2011; Smith & Alloy, 2009; Tanner et al., 2013). For example, even though depressive symptoms was positively correlated with all four subcomponents of rumination and both counterfactual thinking and anticipatory thoughts were significantly positively correlated with drinking to cope motives; only problem-focused thoughts uniquely mediated the positive associations between depressive symptoms and drinking to cope motives. There are a few possible explanations as to why problem-focused thoughts emerged as the strongest facet most relevant in the pathway to problematic alcohol consumption. Problem-focused thoughts involves repeatedly thinking of a problem, but not gaining any kind of resolution of the problem, which is consistent with Nolen-Hoeksema's (1991) notion of rumination as consistently thinking of the causes, consequences, and symptoms of negative affect. This style of thinking appears to reflect a problem-solving deficit and has been associated with problematic coping styles (e.g., drinking to cope), which in turn are related to potentially harmful outcomes (Tanner et al., 2013). Further, unlike the other rumination subcomponents which focus on the voluntariness, suddenness, and intrusiveness of thoughts, problem-focused thoughts also captures a significantly lengthy time (e.g., “Sometimes I realize I have been sitting and thinking about something for hours”; Tanner et al., 2013) which may lead individuals to feel that they have to use some coping strategy (e.g., a maladaptive one) to help alleviate the negative affect or stress.

Clinical Implications

Although our results should be considered preliminary, our findings garner support for the notion that students may be drinking to interrupt negative repetitive thoughts (i.e., problem-focused thoughts) that exacerbate and prolong their depressive moods, rather than simply drinking due to the affective state itself (Ciesla et al., 2011). As a whole, the four rumination subcomponents explained 15% of the variance in drinking to cope motives, which is a medium effect size. Given that rumination is a maladaptive form of cognitive coping (Brewin & Holmes, 2003) and despite the large literature supporting drinking to cope motives as a proximal risk factor for problematic alcohol use (Kuntsche et al., 2005), there are very few interventions that attempt to directly target coping motives among college students in order to reduce problematic alcohol consumption. Given that college is a time associated with increased reports of psychological distress (Bayram & Bilgel, 2008; Eisenberg et al., 2007), future research could examine what factors may decouple the relationship between negative emotional states and maladaptive coping responses (e.g., problem-focused thoughts and drinking to cope) because those associations put emerging adults at a heightened risk for problematic drinking.

For example, a growing body of work by Conrod and colleagues has demonstrated that personality-targeted interventions that target how to cope with certain high-risk personality traits are effective at improving alcohol-related outcomes (Conrod, Stewart, Comeau, & Maclean, 2006; Conrod, Castellanos, & Mackie, 2008; Conrod, Castellanos-Ryan, & Mackie, 2011; Conrod et al., 2013) and drug use outcomes (Conrod, Castellanos-Ryan, & Strang, 2010) among adolescents. Further, there is some evidence that the intervention targeting individuals with high anxiety sensitivity may exert its effect through changing drinking to cope motives (Conrod et al., 2011). Given the present study's results, we have a cognitive variable (i.e., ruminative thoughts) that may be an important target for reducing problematic alcohol consumption, at least among college students who drink to cope. Future empirical work is needed to examine whether preventions/interventions that specifically target ruminative thinking, especially problem-focused thoughts, may decouple the associations between negative emotional states and drinking to cope motives.

Limitations

Given the cross-sectional survey design in the present study, we are unable to demonstrate temporal precedence and/or make causal inferences. Although both theory and research assert drinking motives to be proximal antecedents to the decision to drink alcohol (Dvorak, Pearson, & May, 2014), the relationship between depressive symptoms and rumination is likely bidirectional (see Watkins, 2008 for a review). Thus, the temporal ordering of these variables cannot be demonstrated with cross-sectional survey data alone. The use of microlongitudinal (i.e., ecological momentary assessment) and experimental designs are needed to sort out the temporal ordering of changes in depressive symptoms, rumination, drinking to cope motives, and alcohol-related outcomes. Although we examined drinking to cope motives more generally, researchers have distinguished drinking to cope with anxiety from drinking to cope with depression (Grant et al., 2007). Given our focus on depressive symptoms, it would be beneficial to examine whether the associations we observed are specific to coping with depression motives. Other limitations of the present study included reliance on retrospective self-report measures, which is associated with significant recall biases (e.g., with alcohol use, Ekholm, 2004), and use of a convenience sample, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

In sum, alcohol-related problems have remained a public health concern among college populations and depressive symptoms and drinking to cope motives have consistently predicted increased consequences beyond what can be explained by consumption alone. We sought to further our understanding of how these factors interrelate by examining the role of rumination using a multidimensional approach. Results suggest that depressive symptoms do indeed relate to increased problem-focused thoughts, which in turn relate to increased drinking to cope motives. All three of these constructs are related to increased alcohol consequences. Therefore, albeit a small effect, problem-focused thoughts may be a mechanism through which depressive symptoms relates to maladaptive coping which may place college student drinkers at risk for problematic drinking.

Footnotes

An additional correlation analysis was ran examining social, conformity, and enhancement motives with all study variables of interest within the present study. All three drinking motives had weak positive correlations with depressive symptoms, strong positive correlation with drinking to cope motives, and had weak to moderate positive correlations with both alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Further, social and enhancement motives had weak positive correlations with all four rumination subcomponents. A supplementary table of all correlations are available from the authors on request.

Declaration of Interest: We do not have any conflict of interest that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, our work.

References

- Abrams DB, Niaura RS. Social learning theory. In: Blane HT, Leonard KE, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1987. pp. 131–178. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Conner T, Cullum J, Tennen H. A longitudinal analysis of drinking motives moderating the negative affect-drinking association among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:38–47. doi: 10.1037/a0017530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armey MF, Fresco DM, Moore MT, Mennin DS, Turk CL, Heimberg RG, et al. Alloy LB. Brooding and pondering: Isolating the active ingredients of depressive rumination with exploratory factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Assessment. 2009;16:315–327. doi: 10.1177/1073191109340388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram N, Bilgel N. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2008;43:667–672. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Holmes EA. Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:339–376. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinker JK, Dozois DJA. Ruminative thought style and depressed mood. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1–19. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RA, Shirk SR. Subtypes of rumination in adolescence: Associations between brooding, reflection, depressive symptoms and coping. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:56–65. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Dickson KS, Anderson NL, Neal DJ. Negative repetitive thought and college drinking: Angry rumination, depressive rumination, co-rumination, and worry. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35:142–150. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9355-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. The effect of alcohol on conflict behavior in the albino rat. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1951;12:1–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1956;17:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos N, Mackie C. Personality-targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos-Ryan N, Mackie C. Long-term effects of a personality-targeted intervention to reduce alcohol use in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:296–306. doi: 10.1037/a0022997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos-Ryan N, Strang J. Brief, personality-targeted coping skills interventions and survival as a non-drug user over a 2-year period during adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:85–93. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, O'Leary-Barrett M, Newton N, Topper L, Castellanos-Ryan N, Mackie C, Girard A. Effectiveness of a selective, personality-targeted prevention program for adolescent alcohol use and misuse: A cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:334–342. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Stewart SH, Comeau N, Maclean AM. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral interventions targeting personality risk factors for youth alcohol misuse. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:550–563. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Klinger E. Incentive motivation, affective change, and alcohol use; A model. In: Cox M, editor. Why People Drink. New York, NY: Gardner Press; 1990. pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, Murphy JG. Associations between depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems in European American and African American college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:595–604. doi: 10.1037/a0025807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Pearson MR, Day AM. Ecological momentary assessment of acute alcohol use disorder symptoms: Associations with mood, motives, and use on planned drinking days. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22:285–297. doi: 10.1037/a0037157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Muntaner C, Smith C, Tien A, Ybarra M. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and revision (CESD and CESD-R) In: Maruish ME, editor. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. 3rd. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. Vol. 57. CRC press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Gollust S, Golberstein E, Hefner J. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:534–542. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm E. Influence of the recall period on self-reported alcohol intake. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;58:60–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:352–370. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erceg-Hurn DM, Mirosevich VM. Modern robust statistical methods: an easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. American Psychologist. 2008;63:591–601. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Reynolds B, Skewes MC. Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;19:303–313. doi: 10.1037/a0022720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O'Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire—Revised in undergraduates. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2611–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:719–759. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118\. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: User's guide. Chicago: Scientific Software; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Hustad J, Barnett NP, Strong DR, Borsari B. Validation of the 30-day version of the brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcoholism Clinical Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000171940.95813.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney S, Jones RN, Barnett NP. Gender differences in the effect of depressive symptoms on prospective alcohol expectancies, coping motives, and alcohol outcomes in the first year of college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. Treating addiction as a human process. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Stewart SH, Cooper ML. How stable is the motive-alcohol use link? A cross-national validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised among adolescents from Switzerland, Canada, and the United States. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:388–396. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marroquin BM, Fontes M, Scilletta A, Miranda R. Ruminative subtypes and coping responses: Active and passive pathways to depressive symptoms. Cognition & Emotion. 2010;24:1446–1455. doi: 10.1080/02699930903510212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. Seventh. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. College drinking. 2015 Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/Collegefactsheet.pdf.

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Harrell ZA. Rumination, depression, and alcohol use: Tests of gender differences. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2002;16:391–403. doi: 10.1891/jcop.16.4.391.52526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubormisky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roley ME, Claycomb MA, Contractor AA, Dranger P, Armour C, Elhai JD. The realtionship between rumination, PTSD, and depression symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;180:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Alloy LB. A roadmap to rumination: A review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taku K, Cann A, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Intrusive versus deliberate rumination in posttraumatic growth across US and Japanese samples. Anxiety, Stress and Coping. 2009;22:129–136. doi: 10.1080/10615800802317841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A, Voon D, Hasking P, Martin G. Underlying structure of ruminative thinking: Factor analysis of the Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2013;37:633–646. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9492-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam NT, Earleywine M. Validation of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale—revised (CESD-R): Pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Research. 2011;186:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ER. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:163–206. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER. Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:269–277. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120885.17362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]