Abstract

N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) modifications of RNA are diverse and ubiquitous amongst eukaryotes. They occur in mRNA, rRNA, tRNA, and microRNA. Recent studies have revealed that these reversible RNA modifications affect RNA splicing, translation, degradation, and localization. Multiple physiological processes, like circadian rhythms, stem cell pluripotency, fibrosis, triglyceride metabolism, and obesity are also controlled by m6A modifications. Immunoprecipitation/sequencing, mass spectrometry, and modified northern blotting are some of the methods commonly employed to measure m6A modifications. Herein, we present a northeastern blotting technique for measuring m6A modifications. The current protocol provides good size separation of RNA, better accommodation and standardization for various experimental designs, and clear delineation of m6A modifications in various sources of RNA. While m6A modifications are known to have a crucial impact on human physiology relating to circadian rhythms and obesity, their roles in other (patho)physiological states are unclear. Therefore, investigations on m6A modifications have immense possibility to provide key insights into molecular physiology.

Keywords: Biochemistry, Issue 118, RNA, m6A, Methylation, Demethylase, FTO, Epitranscriptome

Introduction

Dynamic and reversible RNA modifications have important roles in RNA homeostasis. Four decades ago, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modifications were found to be abundant in eukaryotic transcriptomes1. They have diverse functions in messenger RNA (mRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), small nucleolar RNA, transfer RNA, and microRNA2. The m6A modifications of mRNA influence their splicing3, translation4, degradation5, and localization2. Moreover, they affect ribosome biogenesis and microRNA function6. The evolutionary conservation of m6A modifications of RNA is noted in unicellular bacteria to multi-cellular humans7. Delineation of the roles of m6A modifications is currently under extensive exploration. The efforts are expected to provide new insights into transcription control. Recent studies reveal that other chemical modifications of mRNA8 also play critical roles in RNA metabolism.

Circadian rhythms9, stem cell pluripotency10, triglyceride metabolism4, fibrosis11, obesity12, and major depression13 are a few examples of processes where m6A modifications are known to control outcomes. Many circadian clock gene transcripts have m6A sites14. Modulation of m6A methylase or demethylase elicits circadian period changes15. Mettl3, an m6A transferase, is a regulator for stem cell pluripotency. A deficiency of Mettl3 leads to early embryonic lethality and aberrant lineage priming at the post-implantation stage10. A deficiency of fat mass- and obesity-associated (FTO), an m6A demethylase, in adipocytes affects fatty acid mobilization and body weight through posttranscriptional regulation of Angptl44. These studies reveal that m6A not only controls mRNA processing, but also plays critical roles in embryological development and patho-physiology. The function of m6A modifications holds implications for therapeutic considerations in the future.

Several methods are available to measure m6A modifications of RNA16-18. Traditionally, thin layer chromatography (TLC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are used to study the distribution of m6A in several RNAs19,20. Mass spectrometry is a sensitive tool for the detection of m6A modifications in RNA. However, the RNA needs to be excised by RNase into short fragments before analysis by mass spectrometry21. Methyl-RNA immunoprecipitation and sequencing (m6A-Seq)22 immunoprecipitates fragmented RNAs with m6A-specific antibodies and performs parallel RNA sequencing. This method generates transcriptome-wide m6A landscapes. High-resolution mapping of m6A individual-nucleotide-resolution cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (miCLIP) further maps m6A modifications at a single-nucleotide resolution23. Both methods provide details of m6A modification across the whole transcriptome, with specific genes' information. However, quantifications and standardization in both methods are difficult if experiments require the comparison of multiple conditions. Moreover, fragmentations of RNA for m6A-Seq alter the original RNA structure, which may affect native m6A levels. To detect global m6A modifications of RNA and their changes under different experimental conditions, we report a method that employs a modified northern blotting protocol. This method resolves RNA by molecular weight, using gel electrophoresis18. This procedure provides better standardization and quantifications for experiments that involve multiple conditions or samples. It also provides specific m6A modification information for different RNAs, whether rRNA, mRNA, or microRNA.

Protocol

NOTE: The total RNA m6A level includes rRNA, mRNA, and other small RNAs. Since ribosomal RNA has abundant m6A modifications, the measurement of m6A levels will need to consider this fact.

1. RNA Isolation

Using the ribonuclease decontamination solution (sprayed onto paper towels), wipe the pipettes and lab bench surfaces. Wet paper towels with nuclease-free water and wipe down pipettes and lab bench surfaces again.

- RNA Extraction

- Total RNA Isolation

- Using an overhead stirrer, homogenize 50-100 mg of tissue or 5-10 x 106 cells in 1 mL of RNA isolation solution maintained at 4 °C. NOTE: More tissue (100-150 mg) may be required for adipose tissue samples from mice because of the lower RNA concentrations therein. Samples sourced from mouse heart, liver, skeletal muscle, lung, brain, and macrophages have been employed previously4.

- Incubate the sample homogenates for 5 min at room temperature.

- Add 100 µL of 1-bromo-3-chloropropane (BCP) per 1 mL of sample homogenate. Shake the tubes vigorously for 15 s and proceed to isolate total RNA according to the manufacturer's instructions24.

- Polyadenylated mRNA Purification from Isolated Total RNA

- Purify polyadenylated mRNA using available kits or protocols.

- Shake thoroughly to re-suspend each of the following solutions: 2x binding solution, oligo(dT) polystyrene beads, and wash solution. Ensure that the oligo(dT) beads warm to room temperature before use.

- Transfer 120 µL of elution solution per preparation into a tube and heat to 70 °C in a heating block.

- Pipette up to 500 µg of total RNA into a microcentrifuge tube. With nuclease-free water, adjust the volume to 250 µL.

- Add 250 µL of 2x binding solution to the total RNA solution and vortex briefly to mix the contents.

- Add 15 µL of oligo(dT) beads and vortex thoroughly to mix.

- Incubate the mixture at 70 °C for 3 min.

- Remove the sample from the heating block and let it stand at room temperature for 10 min.

- Centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 2 min.

- Carefully remove the supernatant, leaving behind approximately 50 µL.

- Add 500 µL of wash solution to re-suspend the pellet by pipetting.

- Pipette the suspension into a spin filter/collection tube set.

- Centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 2 min. Remove the column from collection tube and discard the flow-through. Return the column to the collection tube.

- Pipette 500 µL of wash solution onto the spin filter.

- Centrifuge at 15,000 xg for 2 min.

- Transfer the spin filter into a fresh collection tube.

- Pipette 50 µL of elution solution heated to 70 °C onto the center of the spin filter.

- Incubate for 2-5 min at 70 °C. Centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 1 min.

- Pipette an additional 50 µL of elution solution heated to 70 °C onto the center of the spin filter.

- Repeat Step 1.2.2.1.18.

- Add 100 µg/mL glycogen, 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.2), and 2.5 volumes of absolute ethanol. Precipitate overnight at -80 °C.

- Centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 25 min at 4 °C. Discard the supernatant.

- Wash the pellet with 1 mL of 75% ethanol. Centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C. Carefully remove the ethanol.

- Dry in air for 3-5 min.

- Add 10 µL of nuclease-free water to dissolve the pellet.

- Store at -70 °C.

- RNA Qualification and Quantification

- Using a spectrophotometer, determine the RNA concentration by noting the absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm. The A260/A280 ratio should be 1.8-2.2.

- Check the RNA sample quality using 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis25. NOTE: The intact eukaryotic total RNA should show intense 28S and 18S rRNA bands. The ratio of 28S versus 18S rRNA band intensity for a good RNA preparation is ~2.

2. Gel Electrophoresis and Transfer

NOTE: The buffer preparation protocols are given in Table 1.

- Formaldehyde Gel Preparation (1%)

- Rinse all electrophoresis equipment with diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) water.

- Melt 2.5 g of agarose in 215 mL of DEPC water completely in a microwave oven.

- Add 12.5 mL of 10x 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer and 22.5 mL of 37% formaldehyde.

- Pour it into the electrophoresis apparatus with a 1.5 mm thick comb.

- Eliminate bubbles or push them to the edges of the gel with a clean comb.

- Allow the gel to solidify at room temperature.

- Sample Preparation

- Mix 1-10 µg of total RNA and 11.3 µL of sample buffer.

- Mix 2 µg of the RNA marker (1 µg/µL) with 11.3 µL of the sample buffer.

- Add nuclease-free water to the samples from 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 to a total volume of 16 µL.

- Heat at 60 °C for 5 min, and then chill on ice.

- Mix 16 μL of the sample from 2.2.3 with 4 μL of tracking dye, which contains 0.1 μg/μL ethidium bromide on ice. CAUTION: Ethidium bromide is possibly teratogenic and toxic if inhaled. Read ethidium bromide safety datasheet.

- Electrophoresis

- Add 200 mL of 10x MOPS buffer to 1,800 mL of ddH2O to make a 1x MOPS running buffer.

- Use the 1x MOPS running buffer to rinse the wells of the gel.

- Pre-run the gel at 20 V for 5 min.

- Load the RNA samples into the wells of the gel.

- Cover with foil to avoid light exposure. Run at 35 V for about 17 h (overnight)

- Examine and photograph the gel under a UV light.

- Transfer

- Cut the gel to remove the unused portion.

- Prepare 500 mL of 10x SSC buffer (250 mL of 20x SSC buffer and 250 mL of DEPC water).

- Wash the gel twice with 10x SSC buffer for 20 min with shaking at 50 rpm.

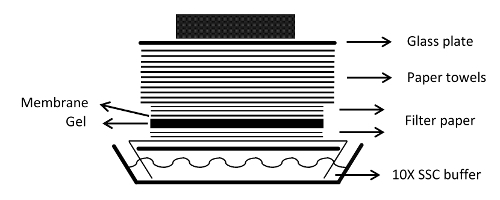

- Cut 1 filter paper sheet large enough to serve as a wick paper, which absorbs transfer buffer from the transfer tray (Figure 1).

- Cut 4 pieces of filter paper to the same size as the gel.

- Cut 1 sheet of positively-charged nylon membrane to the same size as the gel.

- Mark a notch on the gel and the membrane as a marker to ensure the proper orientation.

- Soak the membrane in 2x SSC buffer for 15 min.

- Pour 500 mL of 10x SSC buffer into the transfer tray.

- Lay the large filter paper sheet across the glass plate and wet the filter paper with transfer buffer.

- Roll out any bubbles with a pipette.

- Soak 2 pieces of pre-cut filter paper in transfer buffer and place them on the center of the filter paper from step 2.4.5. Remove any bubbles.

- Lay the gel top-side down on the filter paper.

- Lay the membrane on top of the gel. Align the notches of the gel and the membrane.

- Place 2 pieces of pre-cut filter paper on top of the membrane and wet the filter paper with transfer buffer.

- Remove any bubbles between the layers.

- Apply plastic wrap around the gel to ensure that the towels only soak up buffer passing through the gel and the membrane.

- Stack the paper towels on top of the filter paper.

- Place an oversized glass plate on top of the towels.

- Place a weight on the top of the stack.

- Keep overnight to allow the RNA to transfer from the gel to the membrane.

3. Detection of N6-methyladenosine

- Membrane Crosslinking

- Keep the membrane damp in 2x SSC buffer.

- Place 2 sheets of filter paper immersed with 10x SSC buffer into UV crosslinker.

- Place the membrane on top of the filter paper, with the RNA-adsorbed side facing up.

- Select "autocrosslink mode" (120,000 µJ) and press the "Start" button to initiate the irradiation.

- Examine the membrane and the gel with a UV gel image catcher to confirm the RNA transfer from the gel to the membrane.

- Immunoblotting

- Block the membrane in 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) buffer at room temperature for 1 hr.

- Wash thrice with TBST buffer for 15 min.

- Incubate the membrane overnight in m6A (N6-methyladenosine) antibody solution (1:1,000 in 5% non-fat milk TBST buffer) at 4 °C.

- Wash the membrane thrice with TBST buffer for 15 min.

- Incubate the membrane in the HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody solution (1:2,000 in 5% non-fat milk TBST buffer) for 1 h at room temperature.

- Wash the membrane thrice with TBST buffer for 15 min.

- Apply the enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (0.125 mL per cm2 of membrane).

- Capture the chemiluminescence with the optimum settings of the digital imager, according to manufacturer's instructions26.

- m6A Quantification

- Measure the relative m6A chemiluminescent intensity using the ImageJ software.

- Under the ImageJ software menu, select the "File" option to open the pertinent file.

- Select the "Rectangle" tool from ImageJ and draw a frame around the signals.

- If ribosomal RNA is not the focus of the experiments, avoid the 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA m6A bands for the calculation.

- Click "Command" and "1" to confirm the selected lane.

- Press "Command" and "3" to show the selected plot.

- Click the "Straight" tool and draw lines to separate the segmented area.

- Click the "Wand" tool to record the measurements.

- Export the data.

- Normalize the levels of m6A with the 18S ribosomal RNA band from the ethidium bromide staining.

Representative Results

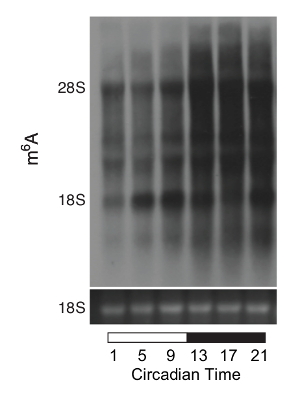

After 14 days in normal light-dark circadian phase, the wild-type mice were placed in constant darkness. The RNAs from the liver were sampled at 4 hr intervals and studied with modified northern blotting. The methylation of rRNAs, mRNAs, and small RNAs were clearly detected (Figure 2). The comparison between different circadian times (CT) can be accurately calculated with the 18S rRNA standard. There was robust circadian oscillation of m6A levels in rRNA, mRNA, and small RNAs.

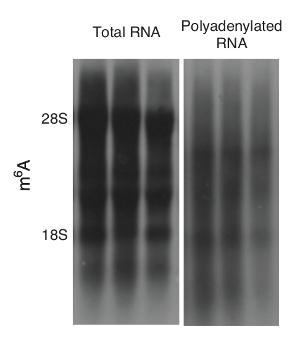

To avoid the interference proffered by rRNA, polyadenylated RNAs can be purified, as in step 1.2.2. After purification, the rRNA can be largely eliminated to allow for better visualization of other RNAs (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Assembling the blot transfer unit. The capillary transfer unit for blotting the RNA to the membrane is shown. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 1: Assembling the blot transfer unit. The capillary transfer unit for blotting the RNA to the membrane is shown. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Circadian rhythm of the m6A levels in C57BL/6J mice. This figure shows the m6A blot of total RNA from livers of wild-type mice sacrificed on the first day of the dark-dark phase after 14 days of a normal light-dark phase at 4 h intervals. The quantification was done using the m6A image density difference between 18S and 28S rRNA. The m6A abundance was normalized to the 18S rRNA band from the formaldehyde gel at the bottom. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Circadian rhythm of the m6A levels in C57BL/6J mice. This figure shows the m6A blot of total RNA from livers of wild-type mice sacrificed on the first day of the dark-dark phase after 14 days of a normal light-dark phase at 4 h intervals. The quantification was done using the m6A image density difference between 18S and 28S rRNA. The m6A abundance was normalized to the 18S rRNA band from the formaldehyde gel at the bottom. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: The m6A blots with or without rRNA. Representative m6A blots of total RNA and polyadenylated RNA from the livers of wild-type mice are shown. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: The m6A blots with or without rRNA. Representative m6A blots of total RNA and polyadenylated RNA from the livers of wild-type mice are shown. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| 1 | 10x MOPS buffer (pH 7.0, protect from light) | |||

| MOPS | 41.85 | g | 0.2 M | |

| Sodium acetate | 4.1 | g | 0.05 M | |

| EDTA, Disodium Salt | 3.7 | g | 0.01 M | |

| DEPC water | ||||

| Total | 1 | L | ||

| Stir at room temperature | ||||

| 2 | 20x SSC buffer (pH 7.0) | |||

| Sodium chloride | 175.3 | g | 3 M | |

| Trisodium citrate | 88.3 | g | 0.3 M | |

| DEPC water | ||||

| Total | 1 | L | ||

| Stir at room temperature, then autoclave | ||||

| 3 | Tracking Dye | |||

| 10x MOPS buffer | 500 | μL | 1x | |

| Ficoll 400 | 0.75 | g | 15% | |

| Bromophenol blue | 0.01 | g | 0.2% | |

| Xylene Cyanol | 0.01 | g | 0.2% | |

| DEPC water | ||||

| Total | 5 | mL | ||

| Store at -20 °C | ||||

| 4 | DEPC water | |||

| Dilute ratio at 1:1,000 of DEPC in ddH2O | ||||

| Stir overnight at room temperature, then autoclave | ||||

| 5 | Sample buffer (protect from light) | |||

| 10x MOPS buffer | 200 | μL | ||

| 37% formaldehyde | 270 | μL | ||

| Formamide | 660 | μL | ||

| Store at -20 °C |

Table 1: Buffers and solutions.

Discussion

Modifications of RNA have important roles in cellular function and physiology. The current understanding of the regulation, function, and homeostasis of these modifications is still being explored and expanded8. Therefore, a precise and gold-standard method to evaluate the modifications of RNA is needed. The modified northern blotting method provides precise quantification of RNA modifications and clear delineation of the modifications in diverse RNAs. Although the method requires at least 3 days, it can be standardized and can be used in various experimental designs. Moreover, with different antibodies, it can detect different RNA modifications27.

It is important to separate different RNAs when analyzing RNA modifications. Ribosomal RNA comprises a large portion of the total amount of RNA28,29. The results from analyzing RNA modifications only in total RNA will represent mostly the changes of rRNA. Methylation and other such modifications of rRNA could potentially mask the changes in other RNAs. With the procedure of gel separation, the modifications of mRNA and other small RNAs can be more accurately analyzed.

Transcriptome-wide mapping with m6A immunoprecipitation and sequencing provides detailed insight into the modification of each type of RNA22. It provides information on the specific RNAs and a resolution of around 80-120 bp. Although m6A-Seq can compare the modifications between different experimental conditions, the selection of proper standards and controls for such experiments is difficult18. Immunoprecipitation is difficult to reproduce, often giving significant variations amongst repeats. Moreover, m6A-Seq requires the fragmentation of RNA samples before immunoprecipitation and sequencing30. The fragmentation process could potentially induce undue influences on the original RNA modifications. If the experiment does not need the specific gene's information but requires different conditions for comparison, the current method provides better visualization and control for diverse experimental setups.

Modification of RNA is an important step in regulating transcriptional control31. However, the homeostasis and the regulatory mechanisms of various RNA modifications under diverse physiological realms are still unclear. Using the present modified northern blotting method, different RNA modifications can be quantified and compared. Furthermore, the changes and regulations of RNA modifications can be investigated in greater detail. In the future, it could also be possible to combine the experimental data from both the classical northern blotting and the modified northern blotting protocols, providing greater insights into RNA biology.

The most important factor determining the success of the modified northern blotting protocol is the integrity of the RNA sample. RNAs with some amount of degradation may yield good classical northern blotting results, but this could potentially have significant impact on the modified northern blotting results. The modifications of RNA in different tissues or cell lines could also vary significantly. It is important to test the suitable RNA sample loads for different tissues before performing the final experiments.

As blotting procedures have been traditionally named after Dr. Southern and different geographical directions, we propose the name "northeastern" blotting for the current technique.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

C.Y.W. received support from the National Health Research Institute (NHRI-EX101-9925SC), the National Science Council (101-2314-B-182-100-MY3, 101-2314-B-182A-009), and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG3B1643, CMRPG3D1002, CMRPG3D0581, CMRPG380091, and CMRPG3C1763).

References

- Thammana P, Held WA. Methylation of 16S RNA during ribosome assembly in vitro. Nature. 1974;251(5477):682–686. doi: 10.1038/251682a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(5):313–326. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y, et al. N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) in RNA: an old modification with a novel epigenetic function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2013;11(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, et al. Loss of FTO in adipose tissue decreases Angptl4 translation and alters triglyceride metabolism. Sci Signal. 2015;8(407):127. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aab3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505(7481):117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berulava T, Rahmann S, Rademacher K, Klein-Hitpass L, Horsthemke B. N6-adenosine methylation in MiRNAs. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):0118438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, et al. Widespread occurrence of N6-methyladenosine in bacterial mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(13):6557–6567. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D, et al. The dynamic N-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fustin JM, et al. RNA-methylation-dependent RNA processing controls the speed of the circadian clock. Cell. 2013;155(4):793–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula S, et al. Stem cells. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naive pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. 2015;347(6225):1002–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.1261417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, et al. FTO modulates fibrogenic responses in obstructive nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2016. SREP18874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jia G, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(12):885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du T, et al. An association study of the m6A genes with major depressive disorder in Chinese Han population. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Yeh JK, Shie SS, Hsieh IC, Wen MS. Circadian rhythm of RNA N6-methyladenosine and the role of cryptochrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;465(1):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Shie SS, Hsieh IC, Tsai ML, Wen MS. FTO modulates circadian rhythms and inhibits the CLOCK-BMAL1-induced transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;464(3):826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn H, Esteller M. An Adenine Code for DNA: A Second Life for N6-Methyladenine. Cell. 2015;161(4):710–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W, et al. Nuclear m(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol Cell. 2016;61(4):507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD, et al. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3' UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149(7):1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz S, Horowitz A, Nilsen TW, Munns TW, Rottman FM. Mapping of N6-methyladenosine residues in bovine prolactin mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(18):5667–5671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick RJ, Noreen D, Munns TW, Perdue ML. Role of N6-methyladenosine in expression of Rous sarcoma virus RNA: analyses utilizing immunoglobulin specific for N6-methyladenosine. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1983;29:214–218. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovina AY, et al. Method for site-specific detection of m6A nucleoside presence in RNA based on high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(4):27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485(7397):201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder B, et al. Single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat Methods. 2015;12(8):767–772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, et al. Simultaneous Quantification of Methylated Cytidine and Adenosine in Cellular and Tissue RNA by Nano-Flow Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Coupled with the Stable Isotope-Dilution Method. Anal Chem. 2015;87(15):7653–7659. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio DC, Ares M, Hannon GJ, Nilsen TW. Nondenaturing agarose gel electrophoresis of RNA. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010;2010(6):5445. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, et al. FTO modulates fibrogenic responses in obstructive nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:18874. doi: 10.1038/srep18874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N-methyladenosine methylome. Nat Chem Biol. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sanschagrin S, Yergeau E. Next-generation sequencing of 16S ribosomal RNA gene amplicons. J Vis Exp. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kukutla P, Steritz M, Xu J. Depletion of ribosomal RNA for mosquito gut metagenomic RNA-seq. J Vis Exp. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mishima E, et al. Immuno-Northern Blotting: Detection of RNA Modifications by Using Antibodies against Modified Nucleosides. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):0143756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klungland A, Dahl JA. Dynamic RNA modifications in disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;26:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]