Abstract

Remodeling of the brain vasculature is a common trait of brain pathologies. In vivo imaging techniques are fundamental to detect cerebrovascular plasticity or damage occurring overtime and in relation to neuronal activity or blood flow. In vivo two-photon microscopy allows the study of the structural and functional plasticity of large cellular units in the living brain. In particular, the thinned-skull window preparation allows the visualization of cortical regions of interest (ROI) without inducing significant brain inflammation. Repetitive imaging sessions of cortical ROI are feasible, providing the characterization of disease hallmarks over time during the progression of numerous CNS diseases. This technique accessing the pial structures within 250 μm of the brain relies on the detection of fluorescent probes encoded by genetic cellular markers and/or vital dyes. The latter (e.g., fluorescent dextrans) are used to map the luminal compartment of cerebrovascular structures. Germane to the protocol described herein is the use of an in vivo marker of amyloid deposits, Methoxy-O4, to assess Alzheimer's disease (AD) progression. We also describe the post-acquisition image processing used to track vascular changes and amyloid depositions. While focusing presently on a model of AD, the described protocol is relevant to other CNS disorders where pathological cerebrovascular changes occur.

Keywords: Medicine, Issue 118, neuroscience, two-photon laser microscopy, neurovascular plasticity, amyloid depositions, thinned-skull, Alzheimer's disease

Introduction

The brain vasculature is a multi-cellular structure, which is anatomically and functionally coupled to neurons. A dynamic remodeling of vessels occurs throughout brain development and during the progression of pathologies of the central nervous system (CNS) 1,2. It is widely accepted that cerebrovascular damage is a hallmark of several CNS diseases, including epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease (AD), traumatic brain injury and encephalitis 3,4. Therefore, tracking cerebrovascular changes in vivo becomes significant when modeling CNS diseases, from onset and into chronic phases. As cerebrovascular modifications often occur concomitantly with neuronal damage or plasticity, imaging of the neuro-vasculature represents a key entry point to decipher CNS disease pathophysiology.

This protocol describes a longitudinal two-photon based procedure to track the remodeling of the cerebrovasculature in a mouse model of AD, a progressive pathology marked by cerebrovascular defects on large and small caliber vessels due to amyloidogenic plaque deposition 5-7. This procedure allows for the visualization of amyloid deposits and tracking of their position and growth with respect to neurovascular remodeling throughout the course of the disease. Vital fluorescent dyes are injected before each imaging session for the visualization of the cerebrovasculature and amyloid plaques in transgenic AD mice8. Repeated imaging sessions of a ROI through a thinned skull transcranial window is non-invasive and the method of choice to assess neurovascular remodeling in the living mouse brain 2,5,9,10.

The procedure below outlines the surgical protocol, image acquisition and processing. The early progression of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) mostly at large leptomeningeal and penetrating arterioles is characterized.

Protocol

Mice are allowed ad libitum access to food, water, and maintained on a 12-hr light-dark cycle. All procedures involving laboratory animals conformed to National and European laws and were approved by the French Ministry for Education and Scientific Research (CEEA-LR-00651-01). A total of 6 transgenic 5xFAD and 4 littermate wildtype (WT) control mice were used for this procedure.

1. Pre-operative Preparation

Intraperitoneally (IP) inject Methoxy-X04 (10 mg/kg) 48 hr before surgery to label Aβ deposits11.

Prepare sterile artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) (120 mM NaCl, 26.2 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 1.3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose; bubble with 95% O2/ 5% CO2 before adding 2.5 mM CaCl2).

Sterilize surgical tools (scissors, forceps, razor blade and drill bit), using an autoclave or a hot bead sterilizer before aseptic surgery.

Clean the surgical bench and microscope plate with 70% ethanol and cover with a clean absorbent cloth.

Inject ketamine/xylazine (75 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively) and the analgesic ketoprofen (2.5 mg/kg) IP.

Check the appropriate level of anesthesia with paw or tail pinches.

Apply sterile ophthalmic ointment to the eyes and shave the fur (nose to ears) while avoiding the whiskers. A depilatory cream can be used as long as it is followed by carefully rinsing with water to prevent skin irritation. Shave the remaining fur with a razor blade. Sterilize the skin with povidone-iodine antiseptic solution.

Place the mouse under the binocular microscope and make a skin incision from the ears to the nose. Pull the skin sideways to expose the skull. Incise the periosteum and repeatedly rinse the skull with sterile aCSF to stop possible bleeding.

2. Vasculature Labeling and Thinned Skull Window Preparation (40 min)

Remove the eye ointment with a cotton tip. Apply a drop of topical ophthalmic anesthetic (tetracaine 1%) and gently pressure the skin around the eye socket to achieve protrusion.

Inject Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated with Dextran (70 kDa) (100 mg/kg or 50 µl of a 50 mg/ml solution; hypodermic insulin needle) in the retro-orbital sinus following the procedure described by Yardeni and colleagues 12. Apply sterile ophthalmic ointment to eyes.

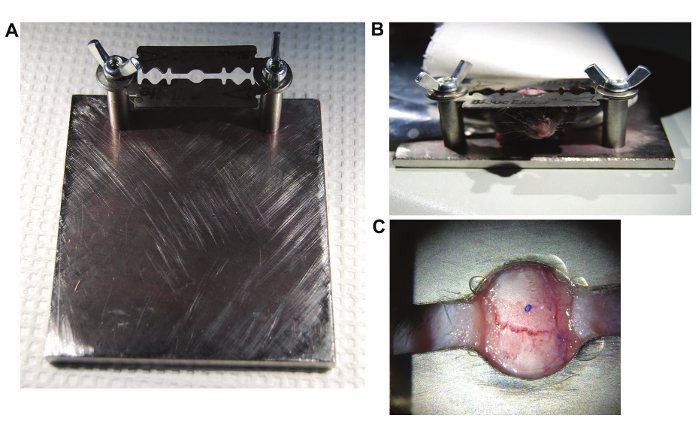

Ensure that the skin is retracted and the skull is clean and dry around the selected imaging area. Apply a small amount of cyanoacrylic glue around the window of the head mount device (consisting of stacked razor-blades, see Figure 1), and glue around the target region applying gentle pressure for several seconds 10.

Pull the ends of the skin to the edge of the window of the head mount device, making sure the area is dry. Secure the skin and the edge of the window with a small amount of veterinary grade cyanoacrylic glue and wait until dry (Figure 1).

Secure the animal at the stage using the head-mount device. Rinse with sterile aCSF and ensure that the well between the skin and head-mount device is perfectly sealed. Wrap the mouse in a survival blanket to maintain normothermia.

Perform thinning of the skull in aCSF solution as previously described10. Note that the scalp is not completely removed. Regularly change the aCSF to clear bone debris and to avoid tissue overheating. Any remaining bone debris can be removed with brief air puffs. The aCSF solution also attenuates vibrations created by drilling. NOTE: The mouse skull thickness varies between 80 to 150 µm depending on the age of the animal and the region of interest.

Using a dental drill (at medium speed and a 0.7 mm burr) start thinning the skull surface in an area 1.0 mm in diameter using a regular vertical motion parallel to the skull and remove most of the spongy bone (first 40 - 70 µm). remember to replace aCSF every 20-30 sec and limit uninterrupted drilling to 3-4 sec. Note that bone near sutures is highly vascularized. Apply aCSF presoaked gelfoam to stop eventual bleeding.

Use a sharp disposable ophthalmic microsurgical blade to continue with the thinning of the skull, being careful not to apply excessive pressure. The final region is of about 0.5 mm in diameter and with a thickness of 20 - 35 µm. NOTE: Due to bone regrowth and scarring, it is necessary to further thin the window at each imaging session.

3. Two-photon Microscopy (45 min)

If necessary, inject with 19 mg/kg ketamine to maintain adequate anesthesia.

Transfer the mouse (fixed to the headmount stage) under the two-photon laser microscope. Using a 20X water immersion objective with a numerical aperture of 1.0, locate the thinned cranial window at the center of the optical field using the epi-fluorescent lamp. Ensure that the objective is always immersed in aCSF.

Start laser scanning with a mode locked pulsed laser (Ti-Sapphire 680-1040nm). Set excitation wavelength at 750 nm to detect the emitted fluorescence of the methoxy-XO4 and FITC-dextran in the blue and green channels respectively. NOTE: The microscope has two beam splitters at 506 nm and 555 nm. Blue light is captured by an NDD detector equipped with a 470 ± 12 nm filter. Green light is captured by a high sensitivity GaAsP detector equipped with a 525 ± 25 nm filter. The maximal laser power emitted from the objective should not exceed 10 mW to avoid laser-induced tissue damage.

Acquire a low magnification stack (500 µm x 500 µm, 512 x 512 pixels; 2 µm step) at a 0.7X numerical zoom to create a 3D map for the precise relocalization of the ROI at later time points.

Acquire a mosaic of 4 high digital magnification images with a 2X numerical zoom (200 µm x 200 µm, 512 x 512 pixels; 1 µm step). Using the imaging software move the window in 200 µm steps to capture all regions. Depth of stacks is typically 250 µm, starting from the pial surface in each image of the mosaic.

Before removing the mouse from the microscope, take a picture or make a hand-drawn 2D map of the pial vasculature for future relocalization of the imaging field.

4. Recovery and Re-imaging

Remove the head-mount device by applying traction while holding the skull underneath. If any glue remains attached to the skull or skin, scrape it off carefully with fine forceps. Suture the scalp and place the mouse in a heated cage to monitor recovery from anesthesia before returning it to the home cage. Apply topical antibiotic cream to the suture and inject ketoprofen (2.5 mg/kg) IP the following 2 days.

Repeat steps 1.1 to 2.5 for repeated imaging sessions. If necessary, shave the bone with a microsurgical blade to ensure optimal quality of the image. NOTE: Additional thinning with the dental drill may be necessary when the interval between imaging sessions is longer than one month.

Position the mouse underneath the microscope using epifluorescent light according to the 2D map of the pial vasculature taken from the previous session (step 3.6).

Start two-photon laser scanning and adjust microscope stage to achieve alignment at the micrometer scale using the 3D map obtained in step 3.4. Proceed to detailed imaging as described in step 3.5.

5. Post-acquisition Three-dimensional Reconstruction and Image Analysis

Obtain three-dimensional reconstructions of the vasculature and the amyloid depositions using the 3D image analysis software such as IMARIS (version used 8.0 and 7.7.2).

Use the Normalize Layer plugin on the image processing menu and contrast change submenu to obtain ideal contrast of the two channels in the entire depth of the image stack.

Open the images from the same region at all time points simultaneously and always process them in parallel in order to compare the different time points.

- Trace vessels using the filament tracer module.

- Click on the filament icon to create a new filament, skip the automatic tracer and choose the auto-path method.

- Be sure the selected channel corresponds to the vascular image and using the select function of the pointer, click at a vessel bifurcation that is conserved across the imaging sessions while holding the shift + control keys to determine a starting point. Use the select function of the pointer and click while holding the shift key to select the end points of the filaments. NOTE: Comparison of the obtained skeletons will show structural changes of the vasculature.

Perform plane by plane analysis to track new plaques. Apply surface module to the blue channel for tracking the growth of Aβ plaques. Click on the surface icon to create a new surface and proceed with the automated surface creation. Use the thresholding method to set and subtract the background signal. The statistics menu provides data relative to the surface of individual amyloid deposits.

Representative Results

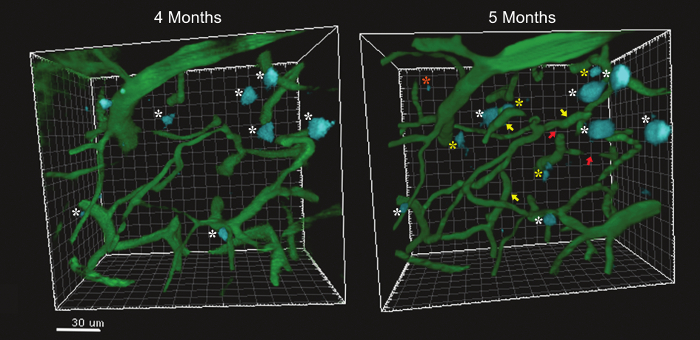

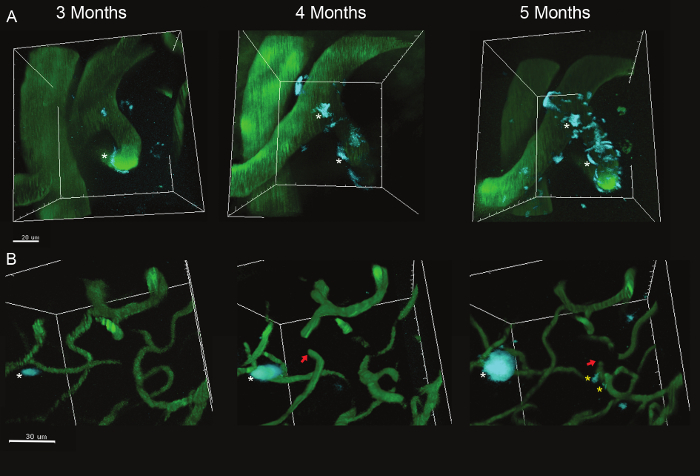

This protocol describes a method for visualizing the cerebrovasculature and amyloid deposits overtime. Fluorescent dyes were injected to label amyloid depositions (methoxy-XO4) 11 and to fill the cerebrovascular lumen (FITC-Dextran)1. 3D image analysis software modules were used to create 3D images of a constant field of view captured at consecutive time points. Representative images obtained in the somatosensory cortex of 5XFAD mice5 (genetic model of AD) show that most Aβ deposits appear between 3 and 4 months of age, growing in the parenchyma (Figure 2) and around penetrating vessels (Figure 3). Plaque deposition occurs simultaneously with significant remodeling and occasional occlusion of the neighboring cerebrovasculature (Figure 2). Only rare instances of plaque size reduction were observed, indicating that this is a process of plaque accumulation. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate that the amyloidogenic load in the parenchyma and around vessels is associated with angiogenesis and vascular occlusion in the somatosensory cortex. The relationship between vascular amyloid plaques and vessel occlusion remains unclear, given that most vascular plaques accumulated on large penetrating arteries, whereas occlusion occurred mostly at small caliber vessels.

Figure 1. Experimental Setup.(A) Head setup; Stage is custom made. Head mount device consists of stacked razor blades built as previously described10. (B) View of the mouse locked in the head mount device. (C) View of the device and skin glued to the skull. Edges are centered on the targeted region. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 1. Experimental Setup.(A) Head setup; Stage is custom made. Head mount device consists of stacked razor blades built as previously described10. (B) View of the mouse locked in the head mount device. (C) View of the device and skin glued to the skull. Edges are centered on the targeted region. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Comparison of Two Reconstructed Images of the Microvasculature and Amyloid Depositions on a 5xFAD Mouse at 4 and 5 Months of Age. Amyloid plaques are indicated with a white asterisk, new plaques appearing at 5 months are indicated by yellow asterisks. A rare instance of plaque reduction is indicated with an orange asterisk Newly formed microvessels are indicated with a yellow arrow while vascular occlusion is indicated with a red arrow. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Comparison of Two Reconstructed Images of the Microvasculature and Amyloid Depositions on a 5xFAD Mouse at 4 and 5 Months of Age. Amyloid plaques are indicated with a white asterisk, new plaques appearing at 5 months are indicated by yellow asterisks. A rare instance of plaque reduction is indicated with an orange asterisk Newly formed microvessels are indicated with a yellow arrow while vascular occlusion is indicated with a red arrow. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3. Large and Small Caliber Vessels in the Somatosensory Cortex at 3, 4 and 5 months of age. (A) Growth of amyloid vascular deposits on large caliber vessels (white asterisks). (B) Amyloid plaques can be also observed on small caliber vessels (yellow asterisks). Red arrows indicate occluded vessels. White asterisks indicated growing amyloid plaques. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3. Large and Small Caliber Vessels in the Somatosensory Cortex at 3, 4 and 5 months of age. (A) Growth of amyloid vascular deposits on large caliber vessels (white asterisks). (B) Amyloid plaques can be also observed on small caliber vessels (yellow asterisks). Red arrows indicate occluded vessels. White asterisks indicated growing amyloid plaques. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

The open-skull technique for in vivo two-photon microscopy offers the advantage of unlimited imaging sessions of large imaging fields13,14. However, this technique also produces inflammation in the region of interest14, often incompatible or impacting neuro-vascular read-outs15. On the contrary, the thinned skull transcranial technique does not result in neuro-inflammation, enabling reliable imaging of the cerebrovascular structures and plaque accumulation10,14. A second advantage presented by this technique is that thinned-skull window success rate can reach up to 80% to 90% for an experienced manipulator. A major setback for success is the lack of appreciation of bone thickness leading to excessive thinning and ultimate fracture; experience and excellent optics of the binocular microscope will limit this problem. A number of limitations do affect this technique however. First, the imaging depth is limited compared to the open-skull procedures. Second, over time, scar tissue overlying the bone can diminish the quality of the transcranial imaging. Third, it is difficult to proceed to more than 4 imaging sessions given that the skull has to be thinned a little more at each session. Consequently, it is important to determine the number of imaging sessions at the beginning of an experiment, in order to optimize the thinning increment between sessions. Alternatively, a chronic transcranial window consisting of a thinned-skull preparation glued with a coverglass has been previously described to limit the regrowth of the bone tissue over time16. Though efficient, we found that this technique only delayed bone regrowth for several weeks eventually interfering with the quality, depth and subcellular resolution of images when re-imaging after longer periods of time (Margarita, Arango-Lievano and Freddy Jeanneteau, unpublished data). Despite its limitations, two-photon transcranial microscopy through repeated thinned skull preparations is a method of choice to track fluorescent markers in chronic disease models where neuro-vascular changes and inflammation occur.

An optimal thinning of the skull represents a major technical step, as pressure applied to the bone should be minimized to avoid bleeding and to ensure a flat skull window. Bleeding and an uneven skull window can facilitate scarring and the uneven regrowth of the bone. Excessive thinning during the first imaging session, overheating after excessive drilling, or laser damage can also compromise the clarity of the signal through the skull window. The latter problems can be controlled by regularly changing the aCSF medium during drilling, cooling the preparation, drilling intermittently, and using clean sharp tools when polishing the bone. Additional critical steps include the (i) fixation of the skull to the head mount plate to reduce the movement associated with respiration, (ii) retro-orbital injection and reliable visibility of all vessels, (iii) mapping the region of interest for future relocation, and (iv) the pre-, per- and post-operative care in between imaging sessions.

The methodology summarized here allows for studies to assess the efficacy and safety of CNS drugs targeting neuro-vascular structures, e.g., molecules reducing or preventing amyloid depositions in the brain parenchyma and on vessels. Additionally, longitudinal two-photon microscopy of the living brain permits tracking of amyloidogenesis and its impact on the neurovasculature at the early stages of AD, prior to onset of cognitive deterioration. Lack of clearance of large amyloid plaques can have deleterious effects on brain vasculature, exacerbating disease pathophysiology17. The advent of new fluorescent vital dyes to label Lewy bodies, synucleopathy, prion aggregates, huntingtin aggregates, support future attainability of neurovasculature remodeling studies during the progression of other neurodegenerative disorders 18. This technique is adapted to several mouse strains combining dyes (SR101, Methoxy-X04, dextrans, lectins) and genetic markers (thy1YFP, CX3CR1-GFP, NG2-dsRed) to investigate cellular interactions in vivo and in experimental models where the structure and function of the neurovasculature deviates from normal physiology.

Disclosures

Authors have no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Ligue Francaise contre l'épilepsie (to M.A-L), Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale Grant AVENIR R12087FS (to F.J), grant from the university of Montpellier (to F.J) and grant from Federation pour la Recherche sur le Cerveau (to N.M). We acknowledge the technical assistance of Chrystel Lafont at the IPAM in vivo imaging core platform facility of Montpellier. We also thank Mary Vernov (Weill Cornell Medical College) for proofreading the manuscript.

References

- Harb R, Whiteus C, Freitas C, Grutzendler J. In vivo imaging of cerebral microvascular plasticity from birth to death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(1):146–156. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteus C, Freitas C, Grutzendler J. Perturbed neural activity disrupts cerebral angiogenesis during a postnatal critical period. Nature. 2014;505(7483):407–411. doi: 10.1038/nature12821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masamoto K, et al. Microvascular sprouting, extension, and creation of new capillary connections with adaptation of the neighboring astrocytes in adult mouse cortex under chronic hypoxia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(2):325–331. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi N, Lerner-Natoli M. Cerebrovascular remodeling and epilepsy. Neuroscientist. 2013;19(3):304–312. doi: 10.1177/1073858412462747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoni P, et al. Cerebrovascular pathology during the progression of experimental Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;88:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough IF, Robel S, Roberson ED, Sontheimer H. Vascular amyloidosis impairs the gliovascular unit in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 12):3716–3733. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig MC, et al. Abeta is targeted to the vasculature in a mouse model of hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(9):954–960. doi: 10.1038/nn1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley H, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26(40):10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston C, et al. Circadian glucocorticoid oscillations promote learning-dependent synapse formation and maintenance. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(6):698–705. doi: 10.1038/nn.3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Pan F, Parkhurst CN, Grutzendler J, Gan WB. Thinned-skull cranial window technique for long-term imaging of the cortex in live mice. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(2):201–208. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, et al. Imaging Abeta plaques in living transgenic mice with multiphoton microscopy and methoxy-X04, a systemically administered Congo red derivative. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61(9):797–805. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.9.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardeni T, Eckhaus M, Morris HD, Huizing M, Hoogstraten-Miller S. Retro-orbital injections in mice. Lab Anim (NY) 2011;40(5):155–160. doi: 10.1038/laban0511-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao VY, et al. In vivo two-photon imaging of experience-dependent molecular changes in cortical neurons. J Vis Exp. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Holtmaat A, et al. Long term, high-resolution imaging in the mouse neocortex through a chronic cranial window. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(8):1128–1144. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner FL, Ransohoff RM, Becher B. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(6):358–372. doi: 10.1038/nrn3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marker DF, Tremblay ME, Lu SM, Majewska AK, Gelbard HA. A thin-skull window technique for chronic two-photon in vivo imaging of murine microglia in models of neuroinflammation. J Vis Exp. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Joseph-Mathurin N, et al. Amyloid beta immunization worsens iron deposits in the choroid plexus and cerebral microbleeds. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(11):2613–2622. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski M, et al. Targeting prion amyloid deposits in vivo. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63(7):775–784. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.7.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]