Abstract

Background

There is growing concern that the quality of inpatient care may differ on weekends versus weekdays. We assessed the “weekend effect” in common urgent general operative procedures.

Methods

The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Florida State Inpatient Database (2007–2010) was queried to identify inpatient stays with urgent or emergent admissions and surgery on the same day. Included were patients undergoing appendectomy, cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, and hernia repair for obstructed/gangrenous hernia. Outcomes included duration of stay, inpatient mortality, hospital-adjusted charges, and postoperative complications. Controlling for hospital and patient characteristics and type of surgery, we used multilevel mixed-effects regression modeling to examine associations between patient outcomes and admissions day (weekend vs weekday).

Results

A total of 80,861 same-day surgeries were identified, of which 19,078 (23.6%) occurred during the weekend. Patients operated on during the weekend had greater charges by $185 (P < .05), rates of wound complications (odds ratio [OR] 1.29, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.05–1.58; P <.05), and urinary tract infection (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.05–1.85; P < .05). Patients undergoing appendectomy had greater rates of transfusion (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.09–1.87; P = .01), wound complications (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.04–1.68; P < .05), urinary tract infection (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.17–2.67; P < .01), and pneumonia (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.05–1.88; P < .05). Patients undergoing cholecystectomy had a greater duration of stay (P = .001) and greater charges (P = .003).

Conclusion

Patients undergoing weekend surgery for common, urgent general operations are at risk for increased postoperative complications, duration of stay, and hospital charges. Because the cause of the “weekend effect” is still unknown, future studies should focus on elucidating the characteristics that may overcome this disparity.

The “weekend effect” refers to inferior outcomes for patients hospitalized on the weekend compared with the weekday. This effect is described in the medical and operative literature in a wide variety of conditions, including myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, childbirth, and intracerebral hemorrhage.1–4 Although mortality serves as a proxy for the weekend effect in many studies, the literature portrays a wide-reaching effect with worse outcomes in many aspects of weekend care. These include patient outcomes such as duration of stay (DOS) and complications, as well as process quality measurements including cost, time to endoscopy in gastrointestinal hemorrhage, use of laparoscopy over open approaches, and waiting time.4–16

Studies regarding the weekend effect in the operative literature consistently demonstrate substandard outcomes for emergent and elective operative indications during the weekend.6–8,10,13–16 The effect likely involves operative performance and perioperative care as both weekend surgery and Friday surgery, with weekend care were associated with inferior outcomes compared with weekday equivalents. Zare et al7 found greater 30-day mortality in patients operated on Friday versus Monday through Wednesday, whereas Worni et al10 found patients undergoing urgent surgery for diverticulitis had a greater risk of Hartman procedure and complications if admitted on the weekend.

Especially problematic is the weekend effect in common urgent procedures that comprise the “bread and butter” of most general surgeons’ repertoire and require prompt operative management to achieve optimal outcomes.17–19 Procedures such as appendectomy, cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, and hernia repair for obstructed/gangrenous hernia are common procedures that any hospital-based operative practice should be able to manage on weekdays and the weekend. Because of the frequency of these conditions and the morbidity and cost associated with added complications, we aimed to characterize the weekend effect in this population by using a large, administrative, all-payer dataset. We hypothesized that patients undergoing urgent common general operations on the weekend would have lesser operative outcomes, mortality, cost, and DOS compared with patients who were operated on a weekday, after adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics.

METHODS

The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Database (SID) from Florida was queried for years 2007–2010. The SID is an administrative, all-payer database aggregated by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Institutional Review Board at our institution deemed the study exempt from review because the data is deidentified and publically available.

Each inpatient observation included International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, codes corresponding to procedures and diagnoses recorded during the stay. Other relevant data elements were the day of the operative procedure, time of admission (weekend vs weekday), type of admission (urgent, emergent), and whether specific diagnoses were present on admission.

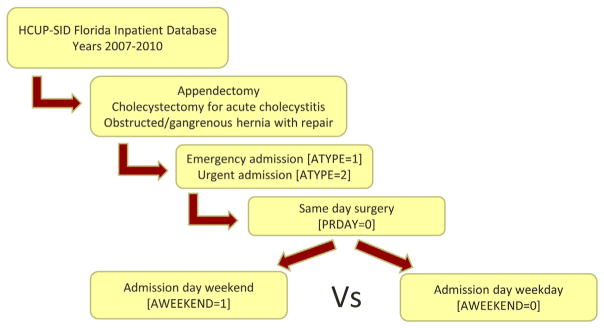

Included were inpatient stays for patients who underwent appendectomy, cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, or hernia repair for obstructed/gangrenous hernia. Only those with an admission classified as emergent or urgent and received surgery on the same day as admission were included in the patient population (Fig 1). Patients were grouped on the basis of time of hospital admission (weekend vs weekday), which also corresponded to date of surgery as all patients had surgery on date of admission.

Fig 1.

Study design. Included were patients who underwent appendectomy, cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, or hernia repair for obstructed/gangrenous hernia who were admitted as urgent or emergent type and received surgery on the same day as admission.

We extracted demographic data from the HCUP-SID, including age, sex, race, type of admission (urgent or emergent), insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, private payer, not insured), type of surgery (appendectomy, cholecystectomy, hernia repair), laparoscopic surgery (Y/N), year, pediatric (Y/N), and the number of chronic conditions. Hospital characteristics were the size (>100 beds), profit status, and location (urban or rural) of the hospital to which patients were admitted. The number of chronic conditions was tabulated by HCUP and defined as a condition that lasts 12 months or longer and meets one or both of the following tests: (1) it places limitations on self-care, independent living, and social interactions; (2) it results in the need for ongoing intervention with medical products, services, and special equipment.

Mortality and DOS were assessed along with the charges of the inpatient stay adjusted for the average charges of each hospital. To adjust for charge, HCUP creates a ratio of single hospital charges to the average nationwide hospital charges that is multiplied to the charges of each inpatient stay. Postoperative complications were defined as the acquisition of an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, code corresponding to the specific complication during the course of the stay that was not present upon admission to the hospital. Assessed were wound complications, blood transfusion, sepsis, pneumonia, and urinary tract infection (UTI). Complication groupings were modified from Worni et al.10

Statistical methods

We compared baseline demographics, hospital characteristics, and outcomes between patients who underwent weekend versus weekday surgery by using the Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables and the Student t test and Kruskal-Wallis tests for normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables, respectively.

Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression modeling was used to examine the association between dichotomous patient outcomes and admissions day (weekday vs weekend) while nesting patients within hospitals. Generalized linear modelling was used to examine the association between continuous patient outcomes and admission day and used a gamma distribution to control for non-normal skew of outcomes.

Both the multilevel, mixed-effects logistic regression model and the generalized linear model controlled for age, sex, race, insurance status, type of surgery, laparoscopic surgery (Y/N), pediatric (Y/N), number of chronic conditions, as well as hospital size, profit status and urban versus rural location. The model controlled for these covariates regardless of the level of significance for the surgery type and outcome tested.

RESULTS

A total of 80,861 admissions met the inclusion criteria, including 61,783 (76.4%) weekday and 19,078 (23.6%) weekend procedures. Exactly 59,963 patients underwent appendectomy, 11,911 underwent cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, and 9,515 underwent hernia repair for obstructed/gangrenous hernia.

Patients undergoing urgent surgery on the weekend were slightly younger (39.3 years ± 21.5 vs 40.2 years ± 21.5; P < .001), more likely to have insurance status uninsured/other (15.9% vs 13.9%; P < .001), and had fewer chronic conditions (1.55 ± 2.2 vs 1.62 ± 2.2 P < .01) (Table I). Weekend stays more often were admitted from the emergency department (97.2% vs 91.2% < .001) and to hospitals with non-for profit status (66.7% vs 65.7% P < .05).

Table I.

Patient- and hospital-level demographics

| Weekday | Weekend | Total | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-level characteristics | ||||

| No. operations | 76.4% (61,783) | 23.6% (19,078) | 80,861 | |

| Age, y | 40.2 ± 21.5 | 39.3 ± 21.5 | 40.0 ± 21.5 | <.001 |

| Sex, % female | 47.7% | 46.5% | 47.4% | .002 |

| NCHRONIC (no. chronic conditions) | 1.62 ± 2.2 | 1.55 ± 2.2 | 1.60 ± 2.2 | .006 |

| Admission from ED | 91.2% | 97.2% | 92.7% | <.001 |

| Race | NS | |||

| White | 67.6% | 67.3% | 67.5% | |

| Black | 9.7% | 9.9% | 9.8% | |

| Hispanic | 21.6% | 21.7% | 21.6% | |

| Asian/other | 1.0% | 1.1% | 1.0 | |

| Insurance | <.001 | |||

| Medicare | 18.7% | 18.0% | 18.5% | |

| Medicaid | 16.1% | 16.8% | 16.3% | |

| Private | 51.4% | 49.4% | 50.9% | |

| Not Insured/other | 13.9% | 15.9% | 14.4% | |

| Admission type | <.001 | |||

| Emergent | 87.5% | 92.3% | 88.6% | |

| Urgent | 12.5% | 7.7% | 11.4% | |

| Procedure | ||||

| Appendectomy | 75.1% (45,026) | 14.9% (14,937) | 59,963 | |

| Cholecystectomy | 81.1% (9,664) | 18.9% (2,247) | 11,911 | |

| Hernia repair | 78.9% (7,511) | 21.1% (2,004) | 9,515 | |

| Hospital-level characteristics | ||||

| Not for profit hospital | 65.7% | 66.7% | 65.9% | .015 |

| Hospital size >100 beds | 96.3% | 95.9% | 96.2% | .024 |

| Urban location | 96.1% | 96.3% | 96.1% | NS |

Values are mean ± SD or %.

ED, Emergency department; NS, not significant.

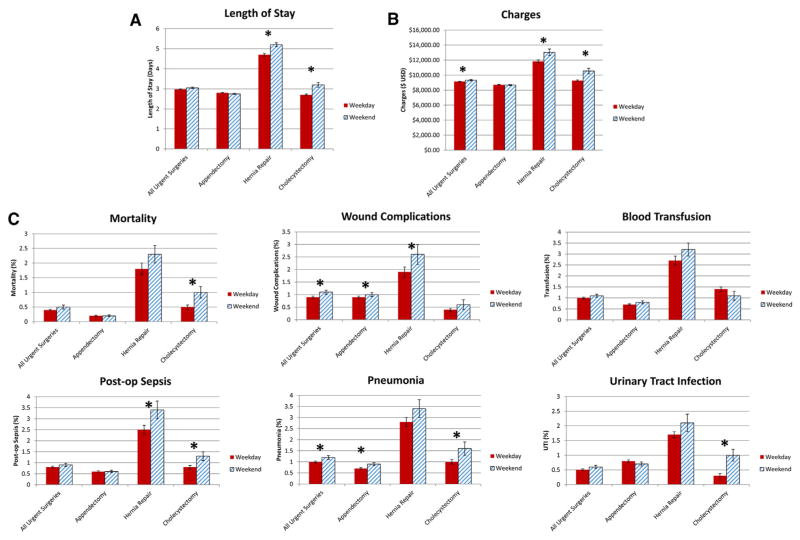

In univariate analysis, all statistically significant differences demonstrated inferior outcomes in the weekend group (Fig 2). Weekend procedures were associated with greater charges ($9,326 ± 80 vs $9,140 ± 38; P <.05), rates of wound complications (1.1% ± 0.08 vs 0.9% ± 0.04; P < .05), and pneumonia (1.2% ± 0.08 vs 1.0% ± 0.04; P < .05). When procedures were considered in isolation, weekend procedures were associated with distinctive subgroups of inferior outcomes. Weekend cholecystectomies were associated with greater mortality (1.0% ± 0.2 vs 0.5% ± 0.07; P < .05).

Fig 2.

Unadjusted comparison of surgical outcomes between weekend versus weekday surgery. Part (A) depicts duration of stay, (B) depicts charges, and (C) depicts rates of specific complications. Outcome means are depicted with corresponding SE. *P < 0.05

After we controlled for patient, hospital, and admission characteristics as well as type of surgery, we found that patients had greater adjusted charges by $185 (P < .05) (Table II). Inpatient mortality was similar between groups; however, patients undergoing weekend surgeries were more likely to develop wound complications (odds ratio [OR] 1.29, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.05–1.58; P < .05) and UTI (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.05–1.85; P < .05) (Table III).

Table II.

Adjusted, nonmorbid outcomes

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| All surgeries | ||

| DOS | 0.011 (−0.01 to 0.032) | NS |

| Charges | 0.020 (0.004–0.035) | .01 |

| Appendectomy | ||

| DOS | −0.0058 (−0.029 to 0.018) | NS |

| Charges | 0.0034 (−0.012 to 0.018) | NS |

| Cholecystectomy | ||

| DOS | 0.097 (0.042–0.15) | .001 |

| Charges | 0.068 (0.023–0.11) | .003 |

| Hernia repair | ||

| DOS | 0.034 (−0.042 to 0.11) | NS |

| Charges | 0.068 (−0.057 to 0.14) | NS |

The effect of weekend surgery on nonmorbid outcomes, after we adjusted for patient and hospital characteristics. Generalized linear modeling coefficient for weekend surgery with corresponding confidence interval and P values is shown. Values in bold indicate significance. CI, Confidence interval; DOS, duration of stay; NS, not significant.

Table III.

Adjusted, mortality and complication outcomes

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| All surgeries | ||

| Mortality | 1.27 (0.91–1.76) | NS |

| Transfusion | 1.17 (0.96–1.43) | NS |

| Wound complications | 1.29 (1.05–1.58) | .02 |

| Sepsis | 1.07 (0.84–1.37) | NS |

| Pneumonia | 1.24 (1.0–1.54) | NS |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.39 (1.05–1.85) | .02 |

| Appendectomy | ||

| Mortality | 1.21 (0.66–2.23) | NS |

| Transfusion | 1.43 (1.09–1.87) | .01 |

| Wound complications | 1.32 (1.04–1.68) | .03 |

| Sepsis | 1.02 (0.72–1.46) | NS |

| Pneumonia | 1.41 (1.05–1.88) | .02 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.76 (1.17–2.67) | .007 |

| Cholecystectomy | ||

| Mortality | 1.91 (0.95–3.83) | NS |

| Transfusion | 0.65 (0.38–1.09) | NS |

| Wound complications | 1.39 (0.61–3.2) | NS |

| Sepsis | 0.81 (0.41–1.58) | NS |

| Pneumonia | 1.10 (0.63–1.94) | NS |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.10 (0.56–2.17) | NS |

| Hernia repair | ||

| Mortality | 1.16 (0.73–1.85) | NS |

| Transfusion | 1.26 (0.89–1.79) | NS |

| Wound complications | 1.29 (0.86–1.96) | NS |

| Sepsis | 1.21 (0.82–1.79) | NS |

| Pneumonia | 1.08 (0.73–1.61) | NS |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.32 (0.83–2.10) | NS |

The effect of weekend compared with weekday admissions on mortality and complications after we adjusted for patient and hospital characteristics. Values in bold indicate significance.

NS, Not significant.

Multivariate subgroup analysis comparing weekend to weekday admission, based on type of operative procedure, demonstrated that patients who underwent appendectomy were more likely to require transfusion (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.09–1.87; P = .01), and acquire wound complications (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.04–1.68; P < .05), UTI (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.17–2.67; P < .01) and pneumonia (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.05–1.88; P < .05) in the multivariate model. Cholecystectomy patients displayed longer DOS (P = .001) and greater charges (P = .003).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated differences in outcomes between patients undergoing common urgent surgeries on weekends versus weekdays. Using the HCUP-SID, we demonstrated that urgent weekend inpatient stays were associated with greater charges and greater rates of wound complications and UTIs. We found weekend cholecystectomies were associated with greater DOS and charges, whereas appendectomies resulted in more transfusions, sepsis, wound complications, and UTIs. Importantly, these differences persisted after we controlled for patient and hospital level characteristics.

Our study is the first to demonstrate the weekend effect in a collection of common urgent general operative procedures. These conditions present with equal frequency throughout the week, and any hospital-based operative practice should be able to manage these patients promptly whether on weekends or weekdays. This finding is in contrast to rare operative emergencies that require subspecialty coverage to achieve optimal outcomes. For such rare cases, perhaps the weekend effect is an unfortunate result of a justified policy, namely that increasing specialist weekend coverage in anticipation of rare events would introduce inefficiencies into an already strapped health care system.

In our series, the weekend effect represents inefficiency already present in the US health care system. The $185 charge per inpatient stay added up to nearly $3.5 million for the 19,078 weekend hospital stays in this study. Although the cause of the weekend effect is currently unknown, interventions designed to improve weekend perioperative care may be justified with the goals of improving health care savings and health outcomes. We believe that cost will provide an important metric for testing interventions designed to protect against the weekend effect.

Our results agree with a growing body of research demonstrating inferior weekend outcomes for operative procedures.6–8,10,12–16 Many studies examine a single procedure, and some included procedures in our study population. Worni et al10 isolated laparoscopic appendectomies using the HCUP National Inpatient Sample and found greater mortality during the weekend. However, after adjustment, no added complications except pulmonary were associated with weekend admission. The authors cite high numbers needed to harm calculations in concluding that differences in weekend care are of negligible significance.

One reason for the difference in complication outcomes between our study and the study of Worni et al might relate to the added capability of the SID to recognize whether a diagnosis was already present in the patient’s chart on admission or whether the diagnosis was added during the patient’s stay. The National Inpatient Sample is unable to distinguish between these 2 possibilities. Studies have indicated between 70 and 93% of secondary conditions were present on admission, suggesting that controlling for present on admission status provides a more accurate representation of whether a diagnosis should be considered a complication of that hospital stay.20–22

Although the HCUP SID provided some clear advantages, the data are limited to Florida and may display regional trends. For example, Florida has an older patient population that may exaggerate the weekend effect because they may have a greater likelihood of developing complications after a lapse of care. Another limitation relates to the methodology of the study. We were not able to capture late Friday night and early Monday morning admissions in the weekend group, even though we hypothesize those admissions would demonstrate the weekend effect. In addition, the cost calculations are limited by a lack of readmission cost data. It is possible that the additional weekend inpatient costs are negated by lower readmission costs.

The etiology of the weekend effect remains unclear. Theories range from lower weekend staffing to less access to diagnostics, reduced specialty coverage with wider cross-coverage, and less experienced physicians manning the weekend shifts.23,24 In addition, surgeons often work with unfamiliar ancillary staff during the weekend, which may affect efficiency and communication. Ricciardi et al24 found increased numbers of residents and decreased staffing levels of nurses and physicians associated with weekend mortality in nonelective hospital admissions. It should be noted that the weekend effect was present in hospitals without residents, and several other hospital characteristics predicted the weekend effect. More focused studies may identify which medical/operative services are benefitted by specific hospital-level characteristics and lead to the development of precise, targeted interventions.

Our group has found that some hospitals do not demonstrate the weekend effect, whereas other hospitals overcome the effect over time.25 Such hospitals may possess qualities that are protective against the weekend effect and identifying these institutional characteristics may offer insight into overcoming this quality lapse in operative care. Studying these qualities in a prospective setting could offer unique insight into the weekend effect and cost effective mechanisms to bolster weekend perioperative care.

In conclusion, patients undergoing weekend surgery for common urgent general operations are at risk for increased postoperative complications, DOS, and hospital charges. In an age of quality improvement, health systems should consider processes that bolster weekend perioperative care. As the cause of the “weekend effect” is still unknown, future studies should focus on elucidating the institutional characteristics that may overcome this disparity.

References

- 1.Aujesky D, Jimenez D, Mor MK, Geng M, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality after acute pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2009;119:962–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.824292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, et al. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1099–109. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowley RW, Yeoh HK, Stukenborg GJ, Medel R, Kassell NF, Dumont AS. Influence of weekend hospital admission on short-term mortality after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:2387–92. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.546572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salihu HM, Ibrahimou B, August EM, Dagne G. Risk of infant mortality with weekend versus weekday births: a population-based study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38:973–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jairath V, Kahan BC, Logan RF, et al. Mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the united kingdom: Does it display a “weekend effect”? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1621–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Waiting for urgent procedures on the weekend among emergently hospitalized patients. Am J Med. 2004;117:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zare MM, Itani KM, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, Khuri SF. Mortality after nonemergent major surgery performed on friday versus monday through wednesday. Ann Surg. 2007;246:866–74. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180cc2e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein SD, Papandria DJ, Aboagye J, et al. The “weekend effect” in pediatric surgery - increased mortality for children undergoing urgent surgery during the weekend. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1087–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr BG, Reilly PM, Schwab CW, Branas CC, Geiger J, Wiebe DJ. Weekend and night outcomes in a statewide trauma system. Arch Surg. 2011;146:810–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Worni M, Schudel IM, Ostbye T, et al. Worse outcomes in patients undergoing urgent surgery for left-sided diverticulitis admitted on weekends vs weekdays: a population-based study of 31 832 patients. Arch Surg. 2012;147:649–55. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:663–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa003376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson HJ, Hall NJ, Bhangu A National Surgical Research Collaborative. A multicentre cohort study assessing day of week effect and outcome from emergency appendicectomy. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:732–40. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL. Weekend hospitalisations and post-operative complications following urgent surgery for ulcerative colitis and crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:895–904. doi: 10.1111/apt.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aylin P, Alexandrescu R, Jen MH, Mayer EK, Bottle A. Day of week of procedure and 30 day mortality for elective surgery: Retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics. BMJ. 2013;346:f2424. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIsaac DI, Bryson GL, van Walraven C. Elective, major noncardiac surgery on the weekend: a population-based cohort study of 30-day mortality. Med Care. 2014;52:557–64. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Worni M, Ostbye T, Gandhi M, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy outcomes on the weekend and during the week are no different: a national study of 151,774 patients. World J Surg. 2012;36:1527–33. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1550-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bickell NA, Aufses AH, Jr, Rojas M, Bodian C. How time affects the risk of rupture in appendicitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kluger Y, Ben-Ishay O, Sartelli M, et al. World society of emergency surgery study group initiative on timing of acute care surgery classification (TACS) World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papandria D, Goldstein SD, Rhee D, et al. Risk of perforation increases with delay in recognition and surgery for acute appendicitis. J Surg Res. 2013;184:723–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casey DE, Jr, Chang K, Bustami RT. Evaluation of hospitalization for infections that are present on admission. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:468–73. doi: 10.1177/1062860611409198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houchens RL, Elixhauser A, Romano PS. How often are potential patient safety events present on admission? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:154–63. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naessens JM, Campbell CR, Berg B, Williams AR, Culbertson R. Impact of diagnosis-timing indicators on measures of safety, comorbidity, and case mix groupings from administrative data sources. Med Care. 2007;45:781–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180618b7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong HJ, Morra D. Excellent hospital care for all: open and operating 24/7. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1050–2. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1715-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricciardi R, Nelson J, Roberts PL, Marcello PW, Read TE, Schoetz DJ. Is the presence of medical trainees associated with increased mortality with weekend admission? BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kothari AN, Zapf MAC, Blackwell RH, Chang V, Mi Z, Gupta GN, et al. Components Of Hospital Perioperative Infrastructure Can Overcome The Weekend Effect In Urgent General Surgery Procedures. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]