Abstract

Calcareous soils are characterized by low nutrient contents, high bicarbonate (HCO3−) content, and high alkalinity. The effects of HCO3− addition under zinc-sufficient (+Zn) and zinc-deficient (−Zn) conditions on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of seedlings of two Moraceae species (Broussonetia papyrifera and Morus alba) and two Brassicaceae species (Orychophragmus violaceus and Brassica napus) were investigated. These four species were hydroponically grown in nutrient solution with 0 mM Zn (−Zn) or 0.02 mM Zn (+Zn) and 0 mM or 10 mM HCO3−. The photosynthetic response to HCO3− treatment, Zn deficiency, or both varied according to plant species. Of the four species, Broussonetia papyrifera showed the best adaptability to Zn deficiency for both the 0 mM and 10 mM HCO3− treatments due to its strong growth and minimal inhibition of photosynthesis and photosystem II (PS II). Brassica napus was sensitive to Zn deficiency, HCO3− treatment, or both as evidenced by the considerable inhibition of photosynthesis and high PS II activity. The results indicated different responses of various plant species to Zn deficiency and excess HCO3−. Broussonetia papyrifera was shown to have potential as a pioneer species in karst regions.

Introduction

Bicarbonate (HCO3−) is the product for the catalysis of carbon dioxide (CO2) hydration by carbonic anhydrase (CA). It can be used as an inorganic carbon source to supplement CO2 in leaf cells [1]. Additionally, HCO3− is an essential constituent of the water-oxidizing complex of photosystem II (PS II). This complex is stabilized by HCO3− by binding to other components of PS II and influences the molecular processes associated with the electron acceptor and electron donor sides of PS II [1,2]. Finally, HCO3− supplies CO2 and H2O through the actions of CA in photosynthetic oxygen evolution under environmental stress [3]. However, excess HCO3− is harmful for crop growth due to the inhibition of protein synthesis and respiration and decreased nutrient absorption [4].

Zinc (Zn) is an essential microelement for plant growth in all kinds of soils. It influences many biological processes, including carbohydrate metabolism, cell proliferation and phosphorus-Zn interactions [5–7]. Zn also serves as an integral component of some enzyme structures, such as CA, alcohol dehydrogenase, and glutamate dehydrogenase [7]. Therefore, Zn deficiency causes the rapid inhibition of plant growth and development, which results in increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to photo-oxidative damage and consequently decreased net photosynthesis and photosynthetic electron transport [8].

Excess HCO3− or Zn deficiency inhibits photosynthesis and PS II, which influences photosynthetic and chlorophyll (Chl) fluorescence parameters [9–11]. HCO3−, which is considered the key factor that influences Fe deficiency chlorosis and Zn deficiency in many plant species [12], is the major anion found in calcareous soils in karst regions. However, few studies have shown how plant growth and photosynthetic physiology react to the dual impact of Zn stress and excess HCO3−. The response to excess HCO3− in different rice genotypes has indicated that Zn-efficient rice cultivars can sustain root growth in the presence of high HCO3− when grown in soils with low Zn availability, whereas root growth in Zn-inefficient genotypes is severely inhibited [13,14].

Karst regions are characterized by calcareous soils with a low bioavailability of plant nutrients (e.g., phosphorus, Zn, and iron), high calcium content (in the form of calcium carbonate), and high alkalinity (pH 7.5 to 8.5) [15]. Zn deficiency in plants is particularly associated with calcareous soils in karst regions, where the HCO3− concentration in surface runoff water is approximately 5 mM [16]. HCO3− is considered an important factor for inhibiting plant growth in calcareous soil, especially in rice and wheat [17]. To grow in these challenging regions, plants must adapt and overcome the prevalent nutrient deficiency in these soils. In a previous study, nine calcifuge and nine acidifuge plants exuded different organic acids from their roots when grown in calcareous soils [18]. Wu and Xing [3] demonstrated that Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) Vent. and Morus alba L. can alternatively absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and HCO3− under excess HCO3− stress. The plants utilized HCO3− in the form of converted CO2 and water, and the conversion was reversibly catalyzed by CA. Thus, different plant species have different physiological response modes that allow them to adapt to environments with low Zn and excess HCO3−.

B. papyrifera and M. alba, which belong to the Moraceae family, are characterized by a rapid growth rate and greater adaptability to low-nutrient and excess-HCO3− environments than other members of the family [19–21]. Orychophragmus violaceus L. Schulz and Brassica napus L. are members of the Brassicaceae family that can grow in karst environments. However, O. violaceus is better than B. napus at accumulating available nutrients from the rhizosphere [22]. Therefore, the different growth environment of B. papyrifera, M. alba, O. violaceus and B.napus influenced difference of adaptability response.

Our previous research focus on the biomass, the physiological and biochemical property such as carbonic anhydrase activity, photosynthesis of Broussonetia papyrifera in Karst soils [19]. As the complexity and universality of Karst soil, whether Zn deficiency or excess bicarbonate is the main factor influencing bicarbonate-use capacity and plant growth was hypothesized under hydroponics. In this study, plant growth and the characteristics of both photosynthetic and Chl fluorescence of four species (Broussonetia papyrifera, Bp; Morus alba, Ma; Orychophragmus violaceus, Ov; Brassica napus, Bn) were investigated under Zn-deficient and excess HCO3− conditions. Furthermore, the effects of Zn stress and HCO3− treatment on the photosynthetic characteristics of the four plant species were analyzed, and the mechanisms underlying various adaptive responses of different plant species were investigated.

Materials and Methods

Plant culture and experimental treatments

Seeds of the four plant species (two Moraceae plants: Broussonetia papyrifera, Bp; Morus alba, Ma; and two Brassicaceae plants: Orychophragmus violaceus, Ov; Brassica napus, Bn) were surface sterilized (5 min in 95% ethanol and 30 min in 10% H2O2 with a wash in sterile water after each treatment), sown and grown for 15 days in plastic pots filled with normal Hoagland nutrient solution. Then, the seedlings were transferred into modified Hoagland nutrient solution containing (mM) KNO3, 5.0; Ca(NO3)2∙4H2O, 4.0; NH4NO3, 1.0; KH2PO4, 0.25; MgSO4∙7H2O, 1.0; H3BO3, 0.05; MnSO4∙4H2O, 0.004; CuSO4∙5H2O, 0.005; Fe(Na)EDTA, 0.03; and (NH4)6Mo7O24∙4H2O, 0.002 with no Zn (Zn-deficient, −Zn) or 0.02 mM ZnSO4∙7H2O (Zn-sufficient, +Zn) combined with no HCO3− (0) or 10 mM (10) HCO3−. The pH was adjusted to 8.0 using 1 M KOH before HCO3− was added to the nutrient solution. The four treatments were named +Zn0 (adequate Zn and no HCO3−), +Zn10 (adequate Zn and 10 mM HCO3− addition), −Zn0 (Zn deficiency and no HCO3−), and −Zn10 (Zn deficiency and 10 mM HCO3− addition). HCO3− was supplied as sodium bicarbonate. The plants were grown in a controlled environment with a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 300 μmol m−2 s−1, a 14-h photoperiod, a temperature of 25 ± 0.5°C and a relative humidity of 55 ± 2%. During the experiments, the solution was changed every two days. Measurements were conducted in duplicate on day 15.

Photosynthetic parameter measurements

Photosynthetic parameters, such as net photosynthetic rate (PN), transpiration (E), stomatal conductance (gs), and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), were measured using a portable LI-6400XT photosynthesis system (LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). The fourth-youngest fully expanded leaf from the top was used for measurement between 9:00 and 11:00 a.m. The photosynthetic active radiation, temperature, and CO2 concentration during measurement collection were 600 μmol m−2 s−1, 25°C, and 380 μmol mol−1, respectively. The water use efficiency (WUE) was calculated as PN/E.

Chl fluorescence measurements

Chl fluorescence parameters were measured using an IMAGING-PAM Chl fluorometer (Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany) that applied the same array of blue light-emitting diodes (peak wavelength, 470 nm) for fluorescence excitation, actinic illumination, and saturating light pulses. Plants were dark-adapted for 30 min prior to measurement using the upper middle fully expanded leaves [23]. The minimum Chl fluorescence (Fo) was determined using a measuring beam, whereas the maximum Chl fluorescence (Fm) was measured during an 800-ms exposure to a saturating light intensity (6000 μmol m−2 s−1). The Fm′ (maximal fluorescence yield of a light-adapted leaf) and steady-state Chl fluorescence (Ft) were determined. The maximum quantum yield of PS II (Fv/Fm) was calculated as (Fm − Fo)/Fm. The effective PS II quantum yield (ΦPS II) was calculated as (Fm′ − Ft)/Fm′. Therefore, the relative photosynthetic electron transport rate (ETR) was calculated as ΦPS II × PPFD × 0.5 × 0.84.

Chl content and biomass measurements

The Chl content was determined for the 3rd and 6th fully expanded leaves (in two leaf-age stages) counted from the top of the plants (three measurements per leaf) using SPAD-502 readings (Konica Minolta Sensing Inc., Osaka, Japan). Each measurement was repeated five times. Leaf, stem, and root samples of plants from each of the four treatments were dried at 105°C for 30 min and then weighed at 70°C to obtain their dry weight (DW).

Zinc concentration measurement in roots, stems and leaves

The dried samples of roots, stems and leaves were digested with HNO3–HClO4, and the Zn concentrations in the plants were determined using a TAS-990 hydride-flame atomic absorption spectrometer (Persee Inc., Beijing, China).

Determination of the variation in growth and photosynthetic characteristics

To compare the plant response to Zn stress and HCO3− treatment, variations in plant biomass, photosynthetic parameters, Chl fluorescence parameters, and Chl content were calculated according to Eqs (1–4).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where G is the plant biomass, photosynthetic parameters, Chl fluorescence parameters, Chl content, or Zn concentration of organs under Zn stress and/or HCO3− treatment; A1 is the influence of HCO3− treatment under +Zn conditions, and the control is the +Zn0 treatment (Eq (1)); A2 is the influence of HCO3− treatment under −Zn conditions, and the control is the −Zn0 treatment (Eq (2)); A3 is the influence of Zn deficiency under no HCO3− conditions, and the control is the +Zn0 treatment (Eq (3)); and A4 is the influence of Zn deficiency under HCO3− treatment, and the control is the +Zn10 treatment (Eq (4)). The unit of Ai (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) is percentage; positive values indicate stimulation, whereas negative values indicate depression.

The plant resistance to HCO3− addition or Zn deficiency according to the Ai value was assessed from the biomass, Chl content, photosynthetic parameters (PN, WUE, gs), Chl fluorescence parameters (ETR, Fv/Fm) and Zn concentration of the organs.

Results

Plant biomass and Chl content

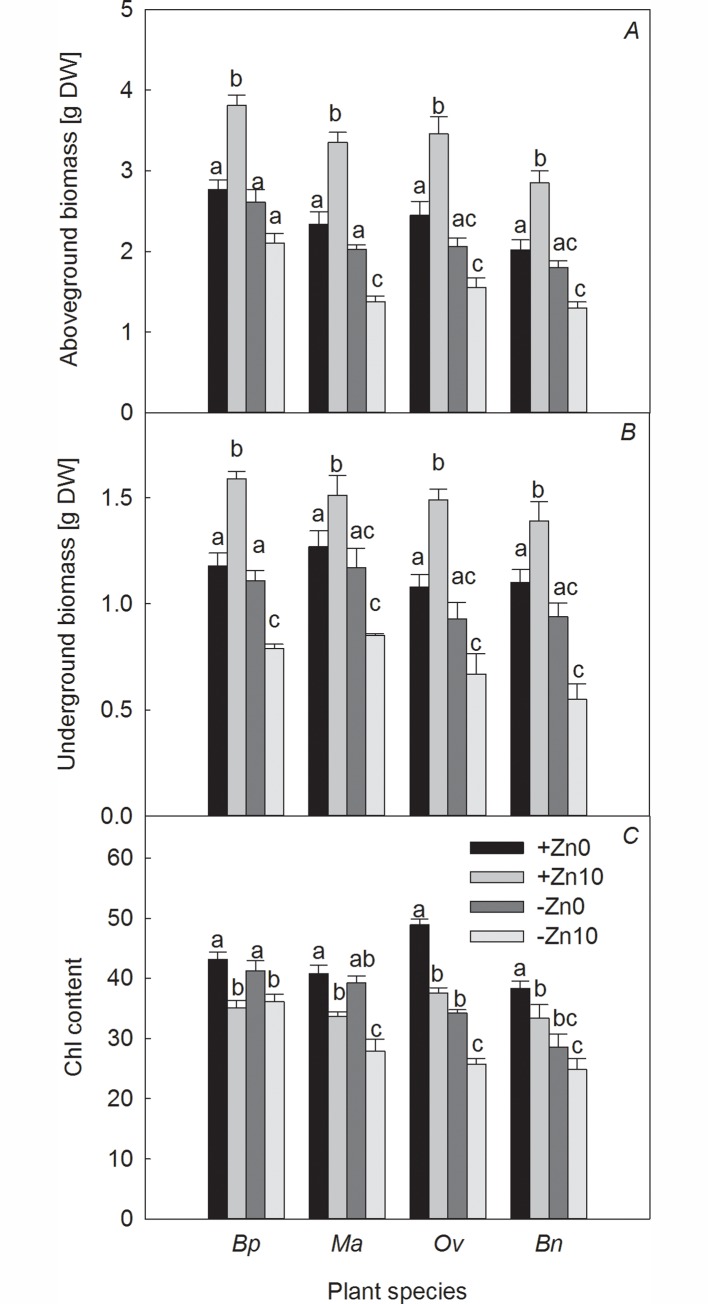

Under +Zn conditions, the biomass of all four plant species increased with the presence of HCO3− (+Zn10 treatment) (Fig 1A and 1B). The addition of HCO3− inhibited the Chl content in all four plant species (Fig 1C). Compared to those under +Zn0 treatments, Ma and Bp showed maximum and minimum increases in aboveground (underground) biomass of 43.16% (37.96%) and 37.55% (18.90%), respectively. As observed in Fig 1, Ov showed the greatest decrease in Chl content.

Fig 1. Effects of Zn and HCO3− on the biomass and Chl content of the four plant species.

Note: Columns with bars indicate the mean ± SE (n = 5). Lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among the four treatments for the same plant species at p < 0.05.

Under −Zn conditions, the biomass of all four plant species decreased with HCO3− addition (−Zn10 treatment) (Fig 1A and 1B). Compared to the −Zn0 treatment, HCO3− addition had the largest adverse effect on the aboveground biomass of Ma and the underground biomass of Bn, as well as the smallest adverse effect on Bp biomass. The decreases in the aboveground biomass of Ma, the underground biomass of Bn and the aboveground (underground) biomass of Bp were 32.02%, 41.49% and 19.54% (27.35%), respectively (Fig 1).

Under no-HCO3− conditions, Zn deficiency had an adverse effect on the biomass and Chl content in all four plant species. Compared to those in the +Zn0 treatments, the decreases in the aboveground biomass of Bp, Ma, Ov and Bn were 5.78%, 13.25%, 15.92% and 10.89%, respectively. The Chl content of the two Brassicaceae plants decreased more significantly than in the two Moraceae species (Fig 1).

Under HCO3−-treatment conditions, Zn deficiency had a significant inhibitory effect on biomass, which had the greatest inhibitory effect on the aboveground biomass of Ma and the underground biomass of Bn (Fig 1A and 1B). Compared to those in the +Zn10 treatment, the decreases in Ma in the aboveground biomass and Bn in the underground biomass were 58.81% and 60.43%, respectively. The Chl content decreased much more in the two Brassicaceae plants than in the two Moraceae species. Bp showed a small increase in Chl content (Fig 1).

Chl fluorescence and photosynthetic parameters

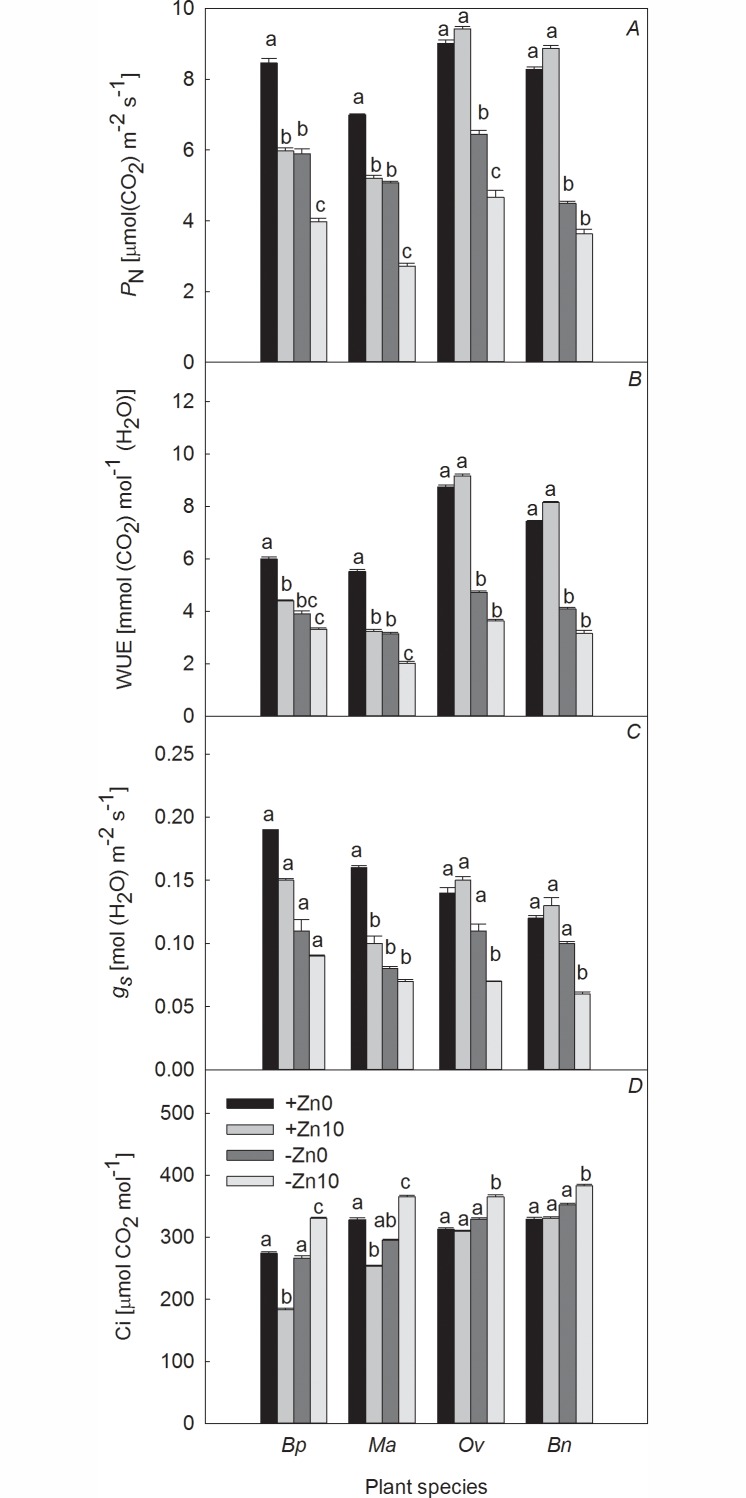

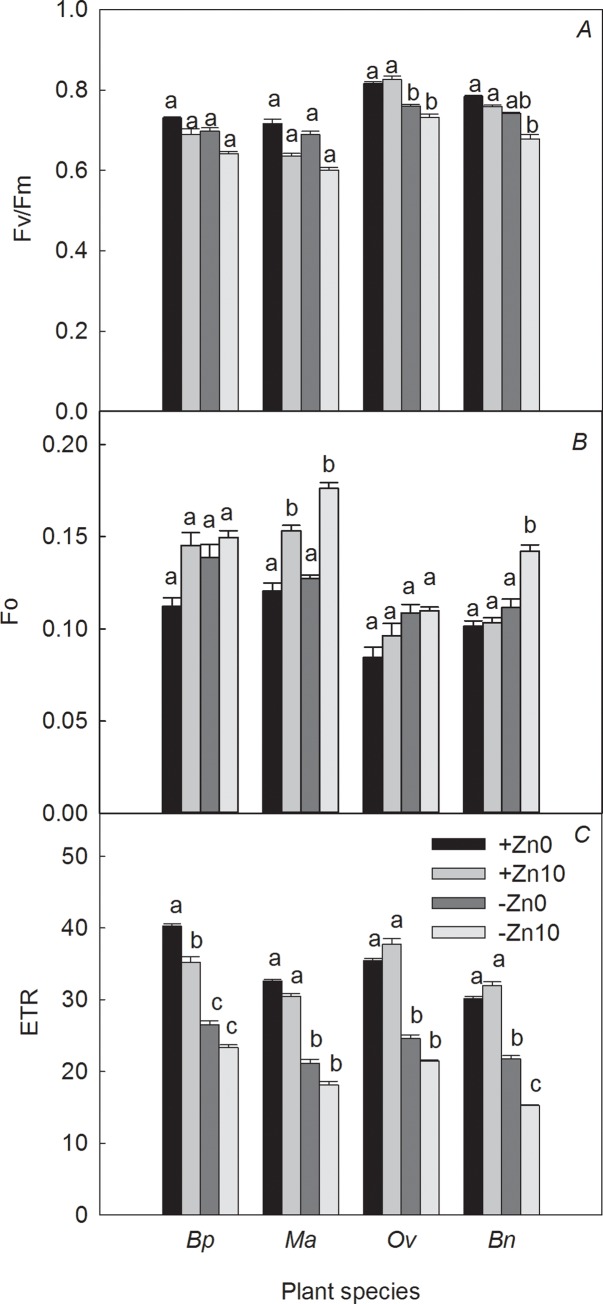

Under +Zn conditions, HCO3− addition increased Fo and decreased PN, gs, Fv/Fm, and ETR. Additionally, it had an adverse effect on the WUE in both Moraceae species. Compared to the +Zn0 treatment, Ma showed the greatest decrease in WUE (41.20%), whereas PN, WUE, gs, Fv/Fm, and ETR increased in both Brassicaceae species, except for the Fv/Fm of Bn and the Fo of Ov (Figs 2 and 3).

Fig 2. Effects of Zn and HCO3− on the photosynthetic parameters of the four plant species.

Note: Columns with bars indicate the mean ± SE (n = 5). Lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among the four treatments for the same plant species at p < 0.05.

Fig 3. Effects of Zn and HCO3− on the Chl fluorescence parameters of the four plant species.

Note: Columns with bars indicate the mean ± SE (n = 5). Lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among the four treatments for the same plant species at p < 0.05.

Under −Zn conditions, the PN and WUE of all species significantly decreased with the addition of HCO3−. Fv/Fm was also slightly inhibited, and Fo increased remarkably in Ma and Bn. Compared with the −Zn0 treatments, HCO3− addition produced the greatest decrease in WUE in Ma and the smallest decrease in WUE in Bp, i.e., 35.46% and 14.87%, respectively. The increases in the Fo of Bp, Ma, Ov and Bn were 7.90%, 38.58%, 6.05% and 27.48%, respectively (Figs 2 and 3).

Under no-HCO3− conditions, Zn deficiency inhibited PN and ETR in all four plant species and had a small adverse effect on Fv/Fm. Compared with the +Zn0 treatments, Zn deficiency led to the maximum inhibition of PN in Bn (45.65%) and the minimum inhibition of WUE in Bp (35.00%). The Fo in Bp and Ov was greater than that in Ma and Bn. The increases in the Fo of Bp, Ma, Ov and Bn were 23.56%, 5.46%, 22.53% and 10.13%, respectively (Figs 2 and 3).

Under HCO3−-treatment conditions, Zn deficiency decreased PN and increased Ci. It also had a small influence on Fv/Fm and dramatically inhibited ETR in all four plant species, in addition to significantly increasing the Fo in Ma. Compared with the +Zn10 treatment, Zn deficiency increased the Fo and decreased the PN, WUE, gs, Fv/Fm, and ETR in the Brassicaceae plants more severely than in the two Moraceae species. The decreases in the PN, WUE, Ci, and ETR of Bp were the smallest, while those parameters of Bn were the greatest under the dual action of HCO3− and low Zn (−Zn10 treatment). The decreases in the PN, WUE and ETR of Bp were 33.50%, 24.55% and 33.68%, respectively, while those of Bn were 59.08%, 61.23% and 52.31%, respectively. The inhibition of growth, photosynthesis, and electron transport under the interaction of Zn and HCO3− exceeded that under Zn deficiency or HCO3− treatment (Figs 2 and 3).

Zn concentration in plant organs

As shown in Table 1, the Zn concentration in four plant organs significantly decreased with Zn deficiency and excess HCO3−. The Zn concentration in the organs of two Moraceae plants was significantly higher than that in the two Brassicaceae plants.

Table 1. Effects of Zn and HCO3− on the Zn concentration (mg Kg-1 DW) in the roots, stems and leaves of the four plant species.

Note: Values are the mean (M) ± standard error (SE) (n = 5). Different lowercase letters indicate a significant difference between the four treatments for the same plant organs at p < 0.05; different capital letters indicate a significant difference in organs of the same species under the same treatment at p < 0.05.

| Plant species | Organs | Zn and HCO3− treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +Zn0 | +Zn10 | −Zn0 | −Zn10 | ||

| B. papyrifera | Roots | 54.74aA ± 1.28 | 42.33bA ± 1.93 | 30.17cA ± 0.98 | 23.67dA ± 0.82 |

| Stems | 62.78aB ± 1.67 | 45.72bAB ± 1.87 | 32.73cA ± 1.01 | 20.23dB ± 0.84 | |

| Leaves | 88.33aC ± 2.70 | 50.27bB ± 2.26 | 36.77cB ± 1.50 | 19.79dB ± 0.56 | |

| M. alba | Roots | 50.64aA ± 1.10 | 41.17bA ± 2.55 | 28.10cA ± 1.23 | 18.26dA ± 1.01 |

| Stems | 57.94aB ± 1.38 | 38.56bAB ± 2.34 | 29.76cA ± 1.21 | 15.17dB ± 0.78 | |

| Leaves | 74.4aC ± 1.50 | 45.73bB ± 1.90 | 27.68cA ± 1.09 | 15.22dB ± 0.73 | |

| O. violaceus | Roots | 23.22aA ± 1.17 | 24.67aA ± 1.34 | 21.86aA ± 0.79 | 14.06bA ± 1.13 |

| Stems | 24.72aA ± 1.09 | 26.28aA ± 1.57 | 14.90bB ± 0.62 | 9.73cB ± 0.87 | |

| Leaves | 32.66aB ± 2.04 | 30.26aB ± 1.29 | 17.72bC ± 1.31 | 11.28cB ± 1.04 | |

| B. napus | Roots | 24.35aA ± 1.29 | 20.18aA ± 1.57 | 18.40aA ± 0.77 | 11.17bA ± 1.09 |

| Stems | 30.34aB ± 2.37 | 29.17aB ± 1.38 | 16.00bA ± 0.53 | 9.74cB ± 0.83 | |

| Leaves | 34.73aC ± 2.55 | 28.72aB ± 1.89 | 15.11bB ± 0.62 | 8.78cB ± 0.69 | |

Under +Zn conditions, the Zn concentration of organs from all four plant species decreased in the presence of HCO3− (+Zn10 treatment), except for that of the roots and stems of Ov. There was a significantly greater decrease in Zn concentration in the organs of the two Moraceae plants than in those of the two Brassicaceae plants. The largest Zn decrease occurred in the leaves of all four plant species, and the increases in the leaves of Bp, Ma, Ov and Bp were -43.09%, -38.53%, -7.35% and -17.30%, respectively.

Under −Zn conditions, the Zn concentration of all four plant species organs decreased with HCO3− addition (−Zn10 treatment), and the decrease in the Zn concentration in the aboveground parts (leaves and stems) was greater than that in the underground parts of the two Moraceae plants. There were no significant differences between the aboveground parts and underground parts of the two Brassicaceae plants.

Under no-HCO3− conditions, Zn deficiency significantly decreased the Zn concentration in the two Moraceae plants. The Zn concentration in the leaves showed the greatest decrease in all four plant species. The decreases in the leaves of Bp, Ma, Ov and Bp were 58.37%, 62.80%, 45.74% and 56.49%, respectively.

Under HCO3−-treatment conditions, the greatest decrease in Zn concentration in all four plant species occurred due to the interaction of Zn deficiency and excess HCO3−, and the Zn concentration decrease in the underground parts (roots) in all four species was greater than 45%, particularly in the roots of Ma, where the Zn concentration decreased by as much as 55.65%. The Zn concentration decrease in the aboveground parts (leaves and stems) of all four species was greater than 55%, particularly in the leaves and stems of Bn, where the Zn concentration decreased by as much as 69.71% and 66.61%, respectively (Table 1).

Discussion

Response of plant growth to excess HCO3− and/or Zn deficiency

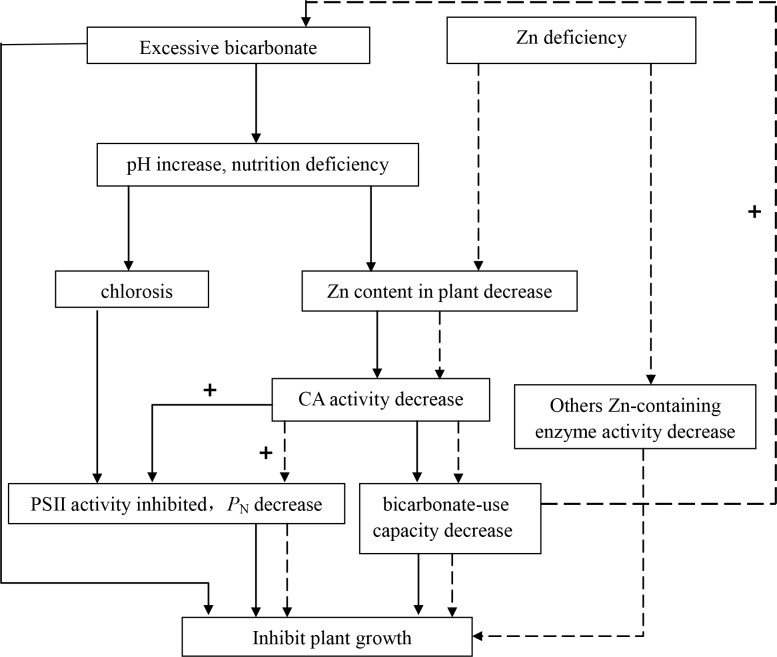

As shown in Fig 4, excess HCO3− influenced plant growth; excess HCO3− results in an intracellular ion charge imbalance through passive diffusion, thus directly inhibiting plant growth [2]. It also inhibited plant growth indirectly through increased pH, which led to a decrease in available nutrient elements, such as Zn, iron, and copper, and then inhibited plant growth via two pathways. In the first pathway, excess HCO3− initially appeared in all plants as chlorosis related to nutrient element deficiency [24], a considerable decrease of photosynthetic capability was associated with the lower Zn contents [25], followed by the inhibition of PS II activity and decreased photosynthetic parameters, such as PN and WUE, and Chl fluorescence parameters, such as Fo, Fv/Fm, and ETR. In the second pathway, excess HCO3− decreased the Zn concentration in plant tissue and the CA activity involved in photosynthetic carbon metabolism, in addition to inhibiting the HCO3−-use capacity because the substrates provided by HCO3− alleviated the CA-catalytic conversion reaction. This effect may be strengthened by the toxicity of HCO3−. Eventually, CA activity decreased, inhibiting PS II activity and reducing inorganic carbon assimilation under excess HCO3− and/or Zn deficiency. In contrast, when the HCO3−-use capacity increased, the toxicity of HCO3− decreased [3,26].

Fig 4. The response of plant growth to excess HCO3− and/or Zn deficiency.

Note: solid-line arrows indicate the mechanism of excess HCO3− on plant growth; dotted-line arrows indicate the mechanism of Zn deficiency on plant growth. CA: carbonic anhydrase. PN: net photosynthetic rate. +: homonymous stimulation effects. PS II: photosystem II.

Zn deficiency decreased the Zn concentration in plant tissue and then inhibited the activity of CA, a Zn-containing enzyme that catalyzes the reversible reaction between CO2 hydration and HCO3− dehydration (Fig 4). Low CA activity resulted in a slight conversion of HCO3− into CO2 and H2O under Zn deficiency [27,28]. As such, Zn deficiency inhibited the plant HCO3−-use capacity and PS II activity due to the presence of excess HCO3−. Meanwhile, Zn deficiency inhibited other Zn-containing enzymes, such as alcohol dehydrogenase and glutamate dehydrogenase, thus inhibiting plant growth [29].

Plant resistance to excess HCO3− and/or Zn deficiency

Different responses arose from different modes of photosynthetic response to excess HCO3− and/or Zn deficiency in various plant species. The resistance of each plant to excess HCO3− or Zn deficiency was different, as shown in Table 2. The total photosynthetic assimilation of inorganic carbon, including CO2 and HCO3−, in Bp under excess HCO3− might exceed its total photosynthetic assimilation without the addition of HCO3−. In addition, the activity of CA in Bp was about 2 times higher than that in Ma on either an sunny days or a cloudy days in Karst soils [19]. Bp had a significantly greater CA activity, at least five times greater than that in Ma under 10 mM bicarbonate treatments in hydroponically culture [3]. High concentrations of bicarbonate decreased the photosynthetic assimilation of inorganic carbon in Bp and Ma in none bicarbonate treaments [3]. Therefore, the growth of Bp increased under these conditions. Bp had a greater HCO3−-use capacity than did Ma [3,26]. Although there was a decrease in PN in Bp, the Zn concentration was greater than that in Ma, and the growth of Bp was stimulated because of the considerable HCO3−-use capacity under excess HCO3− conditions. The conclusion is identical with our previous research conclusions in the field soil cultivations a higher CA activity of Bp supplied both water and CO2 for the photosynthesis of mesophyll cells [3,19]. However, we illuminated Zn deficiency or excess bicarbonate, or both as the crucial factors influenced bicarbonate-use capacity, the photosynthetic response to excess HCO3− or Zn deficiency varied with plant species, and then the difference in plant resistance to nutrition stress.

Table 2. Resistance to excess HCO3− treatment or Zn deficiency under Zn and HCO3− interaction.

Note: The criterion index was expressed by # in terms of Ai: #, very sensitive; # #, sensitive; # # #, weak; # # # #, medium; and # # # # #, strong. Under excess HCO3−, the Ai of biomass, PN (WUE, gs) and ETR (Fv/Fm, Chl content) were more than 20%, 0 and 0, respectively, when the criterion index was # # # # #; 5~20%, -15~0%, and -10~0%, respectively, when the criterion index was # # # #; -15~5%, -30~-15%, and -20~-10%, respectively, when the criterion index was # # #; -30~-15%, -30~-45%, and -30~-20%, respectively, when the criterion index was # #; and less than -30%, -45% and -30%, respectively, when the criterion index was #. Under Zn deficiency, the Ai of biomass, PN (WUE, ETR, Fv/Fm) and Chl content were more than -10%, -15% and 0 when the criterion index was # # # # #; -20~-10%, -25~-15%, and -10~0, respectively, when the criterion index was # # # #; -30~-20%, -35~-25%, and -20~-10%, respectively, when the criterion index was # # #; -40~-30%, -45~-35%, and -30~-20%, respectively, when the criterion index was # #; and -40%, -45% and -30%, respectively, when the criterion index was #.

| Plant species | HCO3− treatment | Zn deficiency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn-sufficient | Zn-deficient | No HCO3− | HCO3− treatment | |

| Bp | # # # # | # # # # | # # # # | # # # |

| Ma | # # # # # | # # # | # # # | # # |

| Ov | # # # # # | # # # | # # # | # # |

| Bn | # # # # # | # # | # # # | # |

WUE was correlated with the HCO3−-use capacity and was also influenced by the photosynthetic rate and inorganic carbon-use capacity [30]. The smallest decrease in the WUE in Bp indicated that Bp had a greater capacity for HCO3− use than did the other three species, and the Zn concentration in the organs of Bp was the highest among the four species. Thus, Bp showed the smallest decrease in growth, and the organ activity of Bp was higher than that in the other three species. Although the PN of Bn slightly decreased, the PS II ETR, gs and Zn availability in Bn organs were severely inhibited. Bn also did not adapt well to excess HCO3− under Zn deficiency. As a result, growth, particularly root growth, was inhibited. Thus, Bp showed the greatest capacity of all four plant species to resist excess HCO3− under Zn deficiency (Table 2).

Few substrates compensate for photosynthesis under the dual influence of Zn deficiency and HCO3− treatment. Therefore, the interaction of Zn deficiency and HCO3− treatment (−Zn10 treatment) severely inhibited growth, photosynthesis, Zn accumulation in plant organs and electron transport. The photosynthesis of Bp was least affected, and the Zn concentration in the Bp organs was the highest, indicating that Bp might have a greater capacity for inorganic carbon use and resistance to Zn deficiency than the other species that were tested. Bp also grew the most rapidly. Bn had the greatest inhibition in photosynthesis and PS II reaction center activity, indicating that it had the weakest resistance to Zn deficiency and HCO3− addition (−Zn10 treatment) (Table 2).

Conclusions

Four plant species showed different photosynthetic responses to Zn deficiency, HCO3− treatment, or both. Bp showed the greatest adaptability to HCO3− treatment, Zn deficiency, or both, which involved the greatest HCO3−-use capacity. Bn was sensitive to Zn deficiency, HCO3− treatment, or both, due to the great inhibition of photosynthesis and PS II reaction center activity. In summary, the plants had different adaptive modes in response to Zn deficiency, HCO3− treatment, or both. According to this research and the previous studies we suggested that Bp has the potential to be a pioneer species for ecological restoration in environments with Zn deficiency and excess HCO3–, such as karst regions.

Supporting Information

(XLS)

Acknowledgments

We also like to thank Xing Deke, Yu Rui and Zhao Yuguo from the Key Laboratory of Modern Agricultural Equipment and Technology, Jiangsu University for their help and support in this research project and making the research successful.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by National Key Basic Research Program of China (grant no. 2013CB956701), by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC0502602), by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31070365), and by the Project on Social Development of Guizhou Province (SY[2010]3043), and by the Research Foundation for Advanced Talents of Anqing Normal University (044-140001000032). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.McConnell IL, Eaton-Rye JJ, van Rensen JJS. Regulation of photosystem II electron transport by bicarbonate In: Eaton-Rye JJ, Tripathy BC, Sharkey TD, editors. Photosynthesis: plastid biology, energy conversion and carbon assimilation. Dordrecht: Springer-Verlag; 2012. pp. 475–500. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Rensen JJ. Role of bicarbonate at the acceptor side of photosystem II. Photosynth Res. 2002;73: 185–192. 10.1023/A:1020451114262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu YY, Xing DK. Effect of bicarbonate treatment on photosynthetic assimilation of inorganic carbon in two plant species of Moraceae. Photosynthetica. 2012;50: 587–594. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alhendawi RA, Römheld V, Kirkby EA, Marschner H. Influence of increasing bicarbonate concentrations on plant growth, organic acid accumulation in roots and iron uptake by barley, sorghum, and maize. J Plant Nutr. 1997;20: 1731–1753. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rengel Z. Availability of Mn, Zn and Fe in the rhizosphere. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2015;15: 397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;7: 504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehman H, Aziz T, Farooq M, Wakeel A, Rengel Z. Zinc nutrition in rice production systems: a review. Plant Soil. 2012;361: 203–226. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae YS, Oh H, Rhee SG, Do Yoo YD. Regulation of reactive oxygen species generation in cell signaling. Mol Cells. 2011;32: 491–509. 10.1007/s10059-011-0276-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Misra A, Srivastava AK, Srivastava NK, Khan A. Zn-acquisition and its role in growth, photosynthesis, photosynthetic pigments, and biochemical changes in essential monoterpene oil (s) of pelargonium graveolens. Photosynthetica. 2005;43: 153–155. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roosta HR, Karimi HR. Effects of alkali-stress on ungrafted and grafted cucumber plants: using two types of local squash as rootstock. J Plant Nutr. 2012;35: 1843–1852. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Jin JY. Photosynthetic rate, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, and lipid peroxidation of maize leaves as affected by zinc deficiency. Photosynthetica. 2005;43: 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCray JM, Matocha JE. Effects of soil water levels on solution bicarbonate, chlorosis and growth of sorghum. J Plant Nutr. 1992;15: 1877–1890. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broadley MR, Rose T, Frei M, Pariasca-Tanaka J, Yoshihashi T, Thomson M, et al. Response to zinc deficiency of two rice lines with contrasting tolerance is determined by root growth maintenance and organic acid exudation rates, and not by zinc-transporter activity. New Phytol. 2010;186: 400–414. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03177.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wissuwa M, Ismail AM, Yanagihara S. Effects of zinc deficiency on rice growth and genetic factors contributing to tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2006;142: 731–741. 10.1104/pp.106.085225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Q, Xu C, Zhang Z, Chen X, Han Z. Precipitation extremes in a karst region: a case study in the Guizhou province, southwest China. Theor Appl Climatol. 2010;101: 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan J, Li J, Ye Q, Li K. Concentrations and exports of solutes from surface runoff in Houzhai Karst Basin, southwest China. Chem Geol. 2012;304–305: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose MT, Rose TJ, Pariasca-Tanaka J, Wissuwa M. Revisiting the role of organic acids in the bicarbonate tolerance of zinc-efficient rice genotypes. Funct Plant Biol. 2011;38: 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ström L, Olsson T, Tyler G. Differences between calcifuge and acidifuge plants in root exudation of low-molecular organic acids. Plant Soil. 1994;167: 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu YY, Liu CQ, Li PP, Wang JZ, Xing D, Wang BL. Photosynthetic characteristics involved in adaptability to Karst soil and alien invasion of paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) vent.) in comparison with mulberry (Morus alba L.). Photosynthetica. 2009;47: 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu CC, Liu YG, Guo K, Zheng YR, Li GQ, Yu LF, et al. Influence of drought intensity on the response of six woody karst species subjected to successive cycles of drought and rewatering. Physiol Plant. 2010;139: 39–54. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu C, Liu Y, Guo K, Fan D, Li G, Zheng Y, et al. Effect of drought on pigments, osmotic adjustment and antioxidant enzymes in six woody plant species in karst habitats of southwestern China. Environ Exp Bot. 2011;71: 174–183. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu YY, Jiang JY, Shuai SW, Chen DM. Approach to mechanism of inorganic nutrition about karst adaptability of Orychophragmus violaceus. Chin J Oil Crop Sci. 1997; 19: 47–49. [Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu W, Li P, Wu Y. Effects of different light intensities on chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics and yield in lettuce. Sci Hort. 2012;135: 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ollat N, Laborde B, Neveux M, Diakou-Verdin P, Renaud C, Moing A. Organic acid metabolism in roots of various grapevine (Vitis) rootstocks submitted to iron deficiency and bicarbonate nutrition. J Plant Nutr. 2003;26: 2165–2176. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xing DK, Wu YY, Yu R, Wu YS, Zhang C, Liang Z. Photosynthetic capability and Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn contents in two Moraceae species under different phosphorus levels. Acta Geochim. 2016; 35: 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu YY, Xing DK, Liu Y. The characteristics of bicarbonate used by plants. Earth Environ. 2011;39: 273–277. [Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopkinson BM, Dupont CL, Allen AE, Morel FM. Efficiency of the CO2-concentrating mechanism of diatoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108: 3830–3837. 10.1073/pnas.1018062108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tavallali V, Rahemi M, Maftoun M, Panahi B, Karimi S, Ramezanian A, et al. Zinc influence and salt stress on photosynthesis, water relations, and carbonic anhydrase activity in pistachio. Sci Hort. 2009;123: 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hafeez B, Khanif YM, Saleem M. Role of zinc in plant nutrition-a review. Am J Exp Agri. 2013;3: 374–391. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu YY, Zhao K, Xing DK. Does carbonic anhydrase affect the fractionation of stable carbon isotope. Geochim Cosmochim Ac. 2010;74: A1148–A1148. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLS)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.