SUMMARY

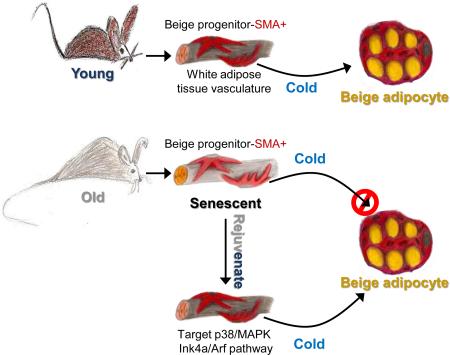

Cold temperatures induce progenitor cells within white adipose tissue to form beige adipocytes that burn energy and generate heat, a potential anti-diabesity therapy. However, the potential to form cold-induced beige adipocytes declines with age. This creates a clinical roadblock to potential therapeutic use in older individuals, who constitute a large percentage of the obesity epidemic. Here we show aging murine and human beige progenitor cells display a cellular-aging-senescence-like phenotype that accounts for their age-dependent failure. Activating the senescence pathway, either genetically or pharmacologically, in young beige progenitors induces premature cellular senescence and blocks their potential to form cold-induced beige adipocytes. Conversely, genetically or pharmacologically reversing cellular aging, by targeting the p38/MAPK-p16Ink4a pathway in aged mouse or human beige progenitor cells, rejuvenates cold-induced beiging. This in turn increases glucose sensitivity. Collectively, these data indicate that anti-aging/senescence modalities could be a strategy to induce beiging thereby improving metabolic health in aging humans.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Brown adipocytes convert glucose and fats into heat thereby warming the body. They do so in part because they express uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), which is a modulator of thermogenic action. Classical brown adipose depots are known to be present in newborn mammals in stereotypical locations (e.g., interscapular). However, in aging humans, classical brown adipose tissue is typically lost (Rogers et al., 2012; Yoneshiro et al., 2011). Another type of brown-like adipocyte, termed beige/brite adipocyte has been identified that form within white adipose depots in response to cold or β-adrenergic activation (Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004; Ghorbani and Himms-Hagen, 1997; Young et al., 1984). Similar to brown adipocytes, beige adipocytes are multilocular, express UCP1 and act as cellular furnaces converting glucose and fatty acids into heat (Golozoubova et al., 2001). It is these latter attributes of cold-inducible beige adipocytes that are of therapeutic interest (Chen et al., 2013; Cypess et al., 2009; Yoneshiro et al., 2013). Recent use of 18fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) scanning shows that adult humans do indeed possess depots of brown adipose tissue. However, human brown fat appears to be more similar to rodent beige fat than classical rodent interscapular brown adipose tissue (Wu et al., 2012). Not only do humans have beige adipose tissue but it also appears to be physiologically relevant: studies show that cold-induced beiging increases energy expenditure (non-shivering thermogenesis) and utilization of free fatty acids and glucose. These two lines of evidence suggest a role of beige adipocytes as a potential therapy for those with diabesity (Blondin et al., 2014; van der Lans et al., 2013).

Cold-induced beige adipocytes appear to originate from a perivascular smooth muscle like progenitor, which expresses several mural cell markers including smooth muscle actin (SMA) and myosin heavy chain 11 (MYH-11) (Berry et al., 2016; Long et al., 2014). Using genetic fate mapping studies, it was observed that upon cold exposure, SMA+ resident mural cells leave their vascular niche to generate UCP1+ multilocular beige adipocytes, but not classical brown adipocytes. Importantly, the vast majority of cold-induced beige adipocytes emanate from this SMA+ perivascular source (Berry et al., 2016). However, a key challenge to realizing the therapeutic promise of beiging for obese and/or diabetic adults is the inability to form cold-induced beige adipocytes in aging humans. This age-dependent failure is apparent even in the mid-30's in humans and has been established in rodents as well (Rogers et al., 2012; Yoneshiro et al., 2011). Such age-dependent failure, in other lineages, is often due to stem cell/progenitor aging or senescence; a cell cycle arrest that is independent of proliferative and growth factor signals (Campisi, 2013). These age-declining stem cell properties translate into reduced overall potential for cell and tissue replacement as well as tissue regeneration in older organisms. The senescence program typically involves: induction of cell cycle inhibitors (e.g., p16Ink4a, p19Arf, and p21), an increase in the senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (Il-6, IGFBP5), and expression of Senescence-Associated beta-galactosidase (SA-βgal) (Campisi, 2013; Sousa-Victor et al., 2014). These age-related and senescence factors not only affect cell cycle progression, but also can block cellular differentiation thus paralyzing these cells from proliferating and differentiating. Several in vitro studies suggest that the cell cycle and senescence machinery may regulate brown adipocyte formation (Hallenborg et al., 2009; Reichert and Eick, 1999). For example, deletion of the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein or members of its complex in mouse embryonic fibroblast induces classical brown adipocyte formation rather than white adipocytes (De Sousa et al., 2014; Hansen et al., 2004). Yet whether Rb or other age-related senescence-associated machinery accounts for age-dependent failure of cold-inducible beige adipocyte formation is unknown. Such knowledge may be essential to devise new therapies to slow and/or perhaps reverse age-related degeneration, with the goal of maintaining healthy adipose tissue with age.

Here we found that murine beige adipocyte formation begins to fail by six months of age, potentially corresponding to human beige failure occurring in the mid-30s. By one-year-of-age, murine beiging is minimal to non-existent. Cellular aging of mural resident beige progenitors, in part, causes this failure. We found that SMA+ beige progenitors from six-month old mice: displayed SA-βgal, up-regulated a host of genes involved in cell cycle arrest, induced the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) program and exhibited an overall senescence-like phenotype. Activating cellular arrest and senescence genetically or pharmacologically disrupted the ability of young animals to form cold-inducible beige adipocytes. Conversely, genetically (deletion of Ink4a/Arf in SMA+ cells) or pharmacologically targeting this pathway reversed this senescence-like process and rejuvenated dysfunctional old beige progenitors; allowing them to once again undergo beige adipogenesis, with concomitant reduction in blood glucose levels. This phenomenon was also observed in isolated BMI-matched human stromal vascular (SV) cells, from young and old patients: that is older human SV cells displayed an increase in senescence activators, expressed SA-βgal and had blunted beige adipocyte differentiation. Yet all three were reversed and beiging was rejuvenated when senescence was inhibited. These results support the notion that cellular aging is a mediator of age-dependent failure to form cold-induced beige adipocytes. Notably, these data suggest that pharmacological targeting the cellular aging/senescence pathway may restore their beiging potential and improve metabolic health in aging humans.

RESULTS

Age-dependent failure of cold-induced beige adipocyte formation

To assess if aging associates with a decrease in beiging potential, we examined C57/BL6 mice that were either two-months (“Young”, postnatal day (P) 60) or six-months (“Old”, P180) old and were maintained for one week at room temperature (RT, 23°C) or exposed to a cold environment (6°C). “Young” mice exposed to cold, formed beige adipocytes that expressed UCP1 and other beige and thermogenic genes; compared to age-matched RT controls (Figures 1A and S1A). Conversely, cold-exposed “Old” mice lacked UCP1+ beige adipocytes and exhibited blunted induction of beige and thermogenic genes (Figures 1B and S1A). We then examined metabolic changes and found that “Old” mice were unable to defend their body temperature, and had elevated sera glucose and free fatty acids compared to “Young” counterparts (Figure 1C-E). These data suggest that beiging, in rodents, may have therapeutic relevance and the loss of beiging during aging may reduce these beneficial attributes. However, some cold-induced changes perdured during aging. For example, both groups decreased overall fat content and increased classical brown adipose tissue weight (Figures 1F and S1B-C).

Figure 1. Age dependent failure of cold-inducible beige fat formation.

Two (Young) or six (Old) month old C57/Bl6 male mice were maintained at room temperature (23°C) or cold exposed (6°C) for seven days. (A-B) H&E staining. (A-B) UCP1 IHC. (C) Rectal temperature. (D) Sera glucose. (E) Free fatty acids. (F) Fat content. Data are means ± SEM; n=6 mice/group. Scale bar = 200 μm. *P<0.05 cold compared to room temperature controls. #P<0.02 Old compared to young cold exposed cohorts. (G) Un-induced UCP1-CreERT2; RFP male mice were aged to postnatal day (P), 60, 120 and 180 and subsequently cold exposed (6°C). Immediately after cold exposure mice were TM induced. IGW were examined for direct RFP fluorescence. L = Lymph node. Scale bar = 4 mm. (H) Beige and thermogenic gene expression from mice describe in (G). §P<0.01 Young compared to Old cold exposed cohorts. (I-J) Beige adipocyte differentiation of SV cells from two or six month old C57/Bl6 male mice: Oil Red O (I) and beige adipocyte markers (J). ##P <0.001 young beige adipocytes compared to undifferentiated SV cells.

As a next step towards potential delineation of relevant mechanisms, we examined expression of beige and thermogenic markers from subcutaneous inguinal adipose depots from two-, four-, and six-month old tamoxifen (TM) pulsed UCP1-CreERT2; RFP, a model of beige adipocyte expression (Berry et al., 2016), male mice after cold exposure (Figure 1G). We administered one dose of TM immediately after cold exposure and examined RFP expression 24 hours later. RFP fluorescence, a surrogate for UCP1 expression (Berry et al., 2016), diminished with aging and appeared completely absent in six-month-old male mice (Figure 1G). In agreement, expression of beige and thermogenic markers decreased in an age-dependent manner (Figure 1H).

To test if the loss of beiging potential was cell autonomous; we isolated the total SV fraction, which contains beige adipose progenitors, from “Young” and “Old” mice and cultured these cells in beige adipogenic media. “Young” SV cells robustly underwent beige adipocyte formation as noted by numerous lipid containing adipocytes and expression of beige adipocyte and thermogenic gene expression (Figures 1I and J and S1D). In contrast, “Old” SV cells demonstrated reduced differentiation potential (Figures 1I and J and S1D). These data imply that the aged progenitor cell source was non-response to beige adipocyte stimuli.

Beige adipocyte progenitors display cellular aging-senescence phenotype

Aging can induce stem/progenitor cell senescence thereby interfering with their differentiation potential (Signer and Morrison, 2013). We tested the hypothesis that “Old” beige progenitors might have undergone a senescence-like conversion thereby blocking their ability to form beige adipocytes in response to cold stimulus. To assess whether “Old” adipose depots contain senescent cells, we isolated “Young” and “Old” depots and probed for expression of Senescence Activated β galactosidase (SA-βgal). “Old”, but not “Young”, adipose depots express SA-βgal (Figure 2A). To test whether beige progenitor cellular aging might be a contributing mechanism to age-dependent failure of cold-induced beiging, we isolated the SV fraction from adipose tissue of “Young” and “Old” mice and evaluated a series of senescence indicators. “Old” SV cells had reduced growth rates and expressed a battery of senescence markers (Lanigan et al., 2011), activators of senescence (p16Ink4a; p19Arf; and p21) and SASP genes (IL-6 and IGFBP5) (Tchkonia et al., 2013) (Figures 2B and S2A and B). Flow cytometry analysis further indicated that total “Old” SV cells had senesced, displaying high levels of Ink4a and low levels of the proliferative marker, Ki67 (Figure S2C).

Figure 2. Old beige progenitors express a cellular aging/senescence phenotype.

(A) Senescence activated (SA) βgal staining of inguinal (IGW) adipose depots from two (Young) and six (Old) month old male mice. Arrow points to SA-βgal positive areas. Scale bar = 4 mm. (B) Expression of senescence genes from two and six month old mice. Data are means ± SEM; n=5 mice/group. *P-value <0.05 Old compared to young cells. (C) Expression of senescence genes from young and old BMI matched human SV cells. **P <0.01 Old compared to young cells. (D-E) Two month and six month old SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP male mice were administered TM; RFP+ cells were FACS isolated at pulse. Cells were stained for Senescence Activated (SA)-βgal (D) or mRNA expression of senescence genes (E) was analyzed. #P<0.05 old SMA/RFP+ compared to young SMA/RFP+ cells. (F) Two or six month old SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP TM pulsed male mice were randomized to the cold for seven days. (G) Sections from mice described in (F) were analyzed for RFP and UCP1. DAPI was used to visualize nuclei. Scale bar = 200 μm.

To examine if these observations extend beyond rodents, we examined human SV cells from “Young” and “Old” non-obese-BMI-matched patients. We first examined SV cell beige adipogenesis and found that “Young” SV cells underwent robust beige adipocyte formation whereas “Old” SV cells had reduced potential (Figure S2D and E). To confirm this, “Young” cells did not display expression of SA-βgal, whereas many old human SV cells expressed SA-βgal (Figure S2F-H). We also found that “Old” human SV cells expressed numerous senescence markers compared to “Young” SV cells (Figure 2C). Thus it appears that both rodent and human beige progenitors exhibit overall reduced beige adipogenic potential and a cellular aging/senescence phenotype.

Recent evidence supports the notion that smooth muscle cells appear to be an endogenous progenitor cell source for cold-induced beige adipocytes, but not for classical brown adipocytes (Berry et al., 2016; Long et al., 2014). To test the possibility that these specific cells might fail to form cold-induced beige adipocytes during aging, we exploited an SMA-CreERT2; Rosa26RRFP (R26RRFP) genetic marking strain that marks beige progenitors (Figure S2I) (Berry et al., 2016). Two (Young) or six (Old) month old SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP male mice were TM pulse-induced (Figure 2D) and SMA/RFP+ beige progenitors were FACS isolated, cultured and stained for SA-βgal. “Old” RFP+ cells expressed SA-βgal compared to RFP+ cells isolated from “Young” mice (Figures 2D and S2J). “Old”, unlike “Young”, SMA-RFP+ beige progenitor cells also expressed elevated levels of senescence markers and lower levels of Ki67 (Figures 2E and S2K). Of note, we did observe a reduction in SMA/RFP+ cell number between young and old cohorts indicating a loss in replicative potential between young and old beige progenitors (Figure S2L). We then examined the ability of aged-progenitors to generate cold-induced beige adipocytes. Two (Young) or six (Old) month old SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP male mice were TM induced and then exposed to cold temperatures for one week (Figure 2F). Cold-stimulated “Young” SMA-RFP+ beige progenitors to form the vast majority of UCP1+ beige adipocytes, as previously reported (Berry et al., 2016). In contrast, “Old” SMA-RFP+ beige progenitors remained confined to the vasculature and did not generate beige adipocytes (Figure 2G).

Activating cellular aging in young progenitors disrupts cold-induced beige formation

Our molecular and cellular data suggest that beige progenitors undergo an age-related-senescence-like phenotype that may prevent them from differentiating into cold-induced beige adipocytes. To test whether cellular senescence of beige progenitors was sufficient to disrupt cold-induced beige adipocyte formation, we developed a mouse model (SMA-rtTA; TRE-p21 denoted SMA-p21-OE) with SMA-dependent inducible expression of p21 combined with the indelible marker RosaR26RFP allele (Figures 3A). We have previously described the SMA-rtTA driver allele, which provides Doxycycline (Dox)-inducible marking, fate mapping, and genetic manipulation of the SMA+ beige progenitors similar to the SMA-CreERT2 strain (Berry et al., 2016). p21 has been shown to activate cell cycle arrest and promote premature cellular senescence in other stem cell lineages (Cheng et al., 2000). Adipose depots and SV cells isolated from the SMA-p21-OE mice showed Dox-dependent increases in expression of p21 (Figure S3A and B). To assess if p21 overexpression in SMA+ cells could initiate a senescence-like phenotype, we administered Dox for 14 days to “Young” SMA-p21-OE mice (Figure 3B). Senescence genes and SASP genes were induced in SMA/RFP+ beige progenitors from SMA-p21-OE mice (Figures 3C). But p21 overexpression did not change the overall SMA-RFP+ cell number (Figure S3C). To determine whether p21 expression could alter the ability of SMA+ beige progenitors to differentiate, we treated “Young” (two-month old) SMA-p21-OE mice with vehicle or Doxycycline (Dox) (Figures 3B). Increased p21 expression did not seem to alter room temperature maintained cohorts based on: temperature, body weight, fat content, and histology (Figure S3D-F and data not shown). In contrast, p21 overexpression did alter the response to cold conditions. For example, p21 overexpression disrupted the potential of “Young” progenitors to form UCP1+ multilocular beige adipocytes and reduced SMA/RFP fate mapping into UCP1+ multilocular beige adipocytes (Figures 3D and E and S3G and H). . In addition to disrupted beige adipocyte formation, cold exposed SMA-p21-OE mice exhibited reduced rectal temperatures, elevated blood glucose levels, and blunted fat loss (Figures 3F-H). We also isolated SV cells from control and SMA-p21 mice and cultured them in Dox-supplemented beige adipocyte differentiation media. SV beige adipogenesis was disrupted in cells over-expressing p21 as assessed by mRNA expression of beige genetic markers (Figure S3I). These data suggest that activating cellular senescence/aging in the beige progenitor lineage disrupts beiging potential in “Young” mice.

Figure 3. Senescence is sufficient to block cold-inducible beige formation.

(A-B) Generation of SMA-rtTA; TRE-Cre; TRE-p21; R26RRFP (SMA-p21-OE) (A). Two-month-old SMA-p21-OE male mice were administered Doxycycline for 14 days then mice were analyzed for senescence markers or were randomized to RT or cold for seven days (B). (C) Mice described in (B) were analyzed for senescence markers. (D-H) UCP1 IHC (D), fate mapping of RFP fluorescence and UCP1 IHC (E), rectal temperature (F), sera glucose (G), and IGW weight (H) from mice described in (B). Data are means ±S.E.M; n=8 mice/group. #P <0.01 young TRE-p21 mutant mice compared to control mice. §P<0.02 cold compared to room temperature. (I-J) Schema- Two-month-old SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP male mice were TM induced, one week later mice were administered vehicle (5% DMSO /water) or PD (250 μg/mouse/day) for five consecutive days. Mice were subsequently analyzed for senescence markers. *P ≤0.05 SMA/RFP+ cells from PD0332991 treated mice compared to SMA/RFP+ cells from vehicle treated mice. (K-O) UCP1 IHC (K), fate mapping of RFP fluorescence and UCP1 IHC (L), temperature (M), glucose (N), and IGW weight (O). Data are means ± S.E.M; n=9 mice/group. *P ≤0.05 PD0332991 treated compared to vehicle treated mice. §P <0.02 cold compared to room temperature. Scale bar = 200 μm.

To assess if the beige progenitor compartment was pharmacologically accessible, we turned to a small molecule inducer of cellular aging, PD0332991 (PD), which inhibits CDK4/6 activity and can activate cell cycle arrest and stimulate an early senescence-like phenotype (Dickson et al., 2013; Michaud et al., 2010). To test if PD could stimulate early onset beige progenitor cellular aging, SV cells were isolated from two-month-old (Young) male mice were treated with vehicle or PD (2.5 μM); PD treatment upregulated senescence genes (Figure S3J). We next administered PD to “Young” SV cells for 15 days then added beige adipogenic media and found that in vitro beiging was disrupted in PD treated cells (Figure S3K). To examine if PD induced early onset aging in SMA+ progenitor cell in vivo, two-month old (Young) TM-induced SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP male mice were treated with vehicle or PD (250 μg/mouse/day) for five days (Figure 3I). We found that PD treatment increased expression of senescence activating genes in FACS isolated RFP+ progenitors (Figure 3J). We next evaluated whether PD could block the ability of “Young” mice to form cold-induced beige adipocytes. To that end, two-month old TM induced SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP male mice were randomized to five days of vehicle or PD and then exposed to cold or room temperatures (Figure 3I). PD treatment of “Young” mice maintained at room temperature did not alter: rectal temperature, sera glucose, white adipose tissue weight, or histology (Figure S3L and data not shown). Cold exposed PD-treated “Young” mice had reduced formation of UCP1+ beige adipocytes and lower beige and thermogenic gene expression (Figures 3K and SL and M). Fate mapping analyses indicated that PD treatment blocked the ability of SMA/RFP+ cells to form multilocular UCP1+ beige adipocytes (Figure 3L). Metabolically, cold-exposed PD treated mice had reduced ability to defend their body temperature, maintain sera glucose levels, and preserve adiposity (Figure 3M-O) Notably, PD treatment did not appear to induce apoptosis or to alter the total SV cell number or the number of SMA/RFP+ cells (data not shown). Collectively, these data suggest that pharmacologically inducing an age-dependent senescence-like phenotype blocks beiging potential in young mice.

Blocking senescence in aged progenitors reverses age-dependent beige failure

Our data indicate that beige progenitors undergo an age-related-senescence-like phenotype and express several senescence markers including p21 and Ink4a/Arf. Previous studies examining cellular senescence in satellite cells of skeletal muscle suggested that deletion of p16Ink4a could reverse senescence and restore skeletal muscle stem cell function (Cosgrove et al., 2014). We next sought to examine if Ink4a/Arf contributed to beige progenitor senescence and beige failure. We first profiled the expression of Ink4a and its repressor, Bmi1, in SMA/RFP+ beige progenitors at various ages and found that Ink4a expression increased with age and, reciprocally, Bmi1 decreased with age (Figure 4A). We next investigated the role of Ink4a/Arf in senescence reversal and beiging rejuvenation by combining an Ink4a/Arffl/fl allele with the TM inducible SMA-CreERT2 (SMA-CreERT2; Ink4a/Arffl/fl; R26RRFP) (Figure 4B). We generated six-month and twelve-month old control and SMA-Ink4a/Arf male mice and administered TM (Figure 4B). Ink4a/Arf deletion in the SMA lineage at both six and twelve months appeared to reverse senescent attributes of old progenitor cells. For example, FACS-isolated RFP+ Ink4a/Arf−/− beige progenitors showed reduced mRNA and protein expression of senescence and aging biomarkers (Figures 4C-G). Yet, under our deletion duration, deleting Ink4a/Arf had little impact on SMA/RFP beige progenitor cell number (Figure S4A). Deleting Ink4a/Arf also restored progenitor beige adipogenesis in vitro, as assessed by Oil Red O staining, triglyceride levels, and beige and thermogenic mRNA expression (Figure 4H-J). We also examined if changes in cellular senescence occurred in “Young” mice. Two-month old control and SMA-Ink4a/Arf male mice and administered TM (Figure S4B). We found that the few senescence genes that were detectable were unaltered in response to Ink4a/Arf deletion (Figure S4C). We also generated SMA-rtTA; TRE-Cre; Ink4a/Arffl/fl mice (Figure S4D) to complement our p21 studies. We administered Dox to six-month old male mice and isolated RFP+ beige progenitors and examined the expression of senescence genes (Figure S4E). We found that senescence-activating genes were reduced in SMA-rtTA; Ink4a/Arf deleted mice compared to old controls (Figure S4F). Collectively, the data indicate that the age-related senescence like phenotype of beige progenitors is reversible upon deletion of Ink4a/Arf.

Figure 4. Deleting Ink4a/Arf in beige progenitors reverses cellular senescence.

(A) Ink4a and Bmi1 expression from C57/Bl6 male mice at denoted ages. *P <0.001 Old compared to young cells. (B) Illustration of genetic alleles used to generate SMA-CreERT2; Ink4a/Arffl/fl; RR26RRFP (SMA-Ink/Arf) mice. (C-F) Schema- Six-month-old SMA-CreERT2; Ink4a/Arffl/fl male mice were TM induced. Fourteen days later, SMA/RFP+ cells were FACS isolated and mRNA (D and E) and protein (F) expression of senescence markers were examined. #P<0.05 mutant SMA/RFP+ cells compared to control SMA/RFP+ cells. (G) 12-month-old SMA-CreERT2; Ink4a/Arffl/fl male mice were TM induced. Fourteen days later, SMA/RFP+ cells were FACS isolated and expression of senescence genes were examined. #P<0.05 mutant SMA/RFP+ cells compared to control SMA/RFP+ cells. (H-J) Un-induced SMA-CreERT2; Ink4a/Arffl/fl cells were cultured in vehicle or TM for 48 hrs. Beige adipocyte differentiation was assessed by Oil Red O (H), triglyceride levels (I) and beige and thermogenic mRNA expression (J). *P <0.001 Old compared to young cells. **P<0.0001 mutant compared to control mice.

We next examined if deleting Ink4a/Arf in the SMA lineage altered the beiging potential of six and twelve-month old male mice (Figure 5A). Deleting Ink4a/Arf in the SMA (SMA-CreERT2) lineage, under our deletion strategy, did not alter room temperature cohorts as assessed by: rectal temperature, adiposity, histology or white adipocyte genetic markers (Figure S5A-D). However, Ink4a/Arf deletion appeared to resuscitate cold-inducible beige adipocyte formation as assessed by: histology, UCP1+ multilocular adipocytes, and expression of beige and thermogenic genes (Figures 5B-E and S5E and F). Examination of SMA-RFP fate mapping under Ink4a/Arf also demonstrate that the vast majority of beige adipocytes emanate from this perivascular SMA+ pool (Figure S5E). We also observed other metabolic improvements in cold-exposed Ink4a/Arf mutant mice: increased ability to defend body temperature, lowered sera glucose levels, and decreased adiposity (Figure 5F-K). We next probed the possibility that the increased beiging, in “Old” mice, might be associated with increased fuel consumption. To test this, we examined tissue-specific glucose uptake in six month aged control and Ink4a/Arf mutant mice after cold exposure. Both subcutaneous and visceral adipose depots from Ink4a/Arf mutant mice had a significant increase in glucose uptake compared to control mice (Figure 5K). Yet, other tissues such as heart and classical brown adipose tissue showed similar glucose uptake (Figure 5K). We also examined beiging potential in “Old” SMA-rtTA; TRE-Cre; Ink4a/Arf mice (Figure S5G). We found that beiging was rejuvenated in these mice as assessed by: ability to defend body temperature, histology, and mRNA expression of beige and thermogenic genes (Figure S5H-K). Yet, deleting Ink4a/Arf in the SMA-CreERT2 lineage did not alter beiging in “Young” mice suggesting an age dependent phenotype (Figure S5L-Q). These data suggest that even with advanced aging deleting cellular aging-senescence related genes can rejuvenate beige progenitors to differentiate into energy utilizing adipocytes.

Figure 5. Reversing cellular aging/senescence is sufficient to restore cold-inducible beige formation.

(A-L) Six and twelve month old SMA-CreERT2; Ink4a/Arffl/fl male mice were TM induced and then cold exposed for seven days (A). (B-C) H&E staining and UCP1 IHC. (D-E) mRNA of beige and thermogenic genes. F-G) Rectal temperatures. H-I) Sera glucose. J-K) Fat content. L) Glucose uptake. Data are means ±S.E.M; n=4-9 mice/group. *P<0.001 SMA-CreERT2; Ink4a/Arffl/fl mutant mice compared to control mice. #P<0.02 cold exposed mice compared to room temperature mice. §P<0.01 twelve month old SMA-CreERT2; Ink4a/Arffl/fl mutant mice compared to aged matched control mice. **P≤0.05 SMA-CreERT2; Ink4a/Arffl/fl mutant mice compared to control mice. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Pharmaceutically inhibiting senescence restores aged progenitors’ beiging potential

We next explored a pharmacologic strategy to reverse cellular aging and senescence as a possible method to rejuvenate the differentiation potential of beige progenitors. One potential therapeutic entry point is the p38/MAPK pathway, which can control senescence signaling and is an upstream regulator of the Ink4a/Arf pathway (Cosgrove et al., 2014). For example, p38/MAPK promotes skeletal muscle satellite cell senescence and small molecule p38/MAPK inhibitors restored satellite cell function and promoted muscle regeneration in vivo (Bernet et al., 2014; Cosgrove et al., 2014). To evaluate if p38/MAPK activity was enhanced in aged beige progenitors, we examined the phosphorylation status of p38/MAPK in “Young” and “Old” SMA/RFP+ beige progenitors using flow cytometry. The data indicated that “Old” progenitors had increased p38/MAPK phosphorylation (Figure S6A). We next assessed whether increased phosphorylation of p38/MAPK had functional consequences on aged-beige progenitors in cell culture studies. Total SV cells were isolated from aged murine subcutaneous adipose depots and treated with vehicle or SB202190 (SB, 5 μM every 24 hours), a p38/MAPK inhibitor that dampens kinase activity by decreasing p38/MAPK phosphorylation (Figure 6A). SB treatment reduced the expression of senescence-associated genes and induced Ink4a/RB target genes indicative of reversed senescence (Figure 6B). This was also true when SV cells from “Old” humans were treated with SB: reduced senescence activating genes and increased senescence inhibitory genes (Figure 6C). We also examined if SB rejuvenated human SV cells by examining SA-βgal staining and found that SB reduced the number of SA-βgal positive cells suggesting a reversal (Figure 6D-F). To test if human SV cells were rejuvenated and adopted progenitor characteristics, we tested their potential to undergo beige adipocyte differentiation (Figures 6G and S6B). Old human SV cells that received SB had robust beiging potential compared to vehicle controls (Figures 6G and S6B).

Figure 6. Pharmacologically targeting p38/MAPK in old SMA+ mural cells rejuvenates beige formation.

(A-C) Total SV cells were isolated from six month old C57/Bl6 male mice (A, B) or SV cells generated from aged human samples. Cells were treated with vehicle or SB202190 (5 μM) for 15 consecutive days. mRNA of senescence markers was examined. *P <0.01 Old compared to young murine cells. *P <0.05 Old compared to young murine cells. (D-F) Human SV cells were treated with vehicle or SB for 15 consecutive days. Subsequently, SA-βgal staining was performed (E) and positive cells were quantified (F). (G) Cells described in (D) were assessed for beige adipogenesis by Oil Red O staining. (H-K) Six month old TM induced SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP male mice were administered vehicle or SB (75 μg/mouse/day) for five consecutive days (H). RFP+ cells were counted (I) and FACS isolated and examined for phosphor-p38/MAPK and denoted proteins (I, J) and expression of senescence genes (K). Data are means ±S.E.M; n=4 mice/group. #P<0.03 SB202190 treated RFP+ cells compared to vehicle treated RFP+ cells.

We next probed the possible in vivo relevance by treating six-month old TM induced SMA-R26RRFP fate mapping male mice with vehicle or SB (75 μg/mice/day). After five days, we assessed SMA/RFP+ beige progenitors by flow cytometry (Figure 6H). Although SB did not alter the number of SMA/RFP+ cells nor total p38 expression, it did decrease the phosphorylation status of p38 and also reduced the protein levels of Ink4a and p21 (Figure 6I and J). SB also reduced the mRNA levels of senescence activators and upregulated the expression of senescence inhibitors suggesting this reversal occurs fairly rapidly (Figure 6K).

Our in vitro and ex vivo data suggested that SB targets SMA cells and reverses the senescence machinery allowing them to form beige adipocytes. We next pursued if SB could alter beiging in vivo in SMA-RFP mice under cold temperatures. TM was administered to six-month-old SMA-RFP male mice. After a seven day TM washout period, mice were administered SB for five days and randomized to room or cold temperatures (Figure 7A). SB treated mice maintained at room temperature did not show altered: rectal temperature, sera glucose, food intake, tissue weights or tissue histology (adipose tissue and other organs) (Figure S7A-F). Conversely, cold exposed SB-treated mice, compared to vehicle-treated littermates, had: increased UCP1+ immunostaining, increased beige gene expression, increased ability to defend body temperature; decreased blood glucose levels and decreased adipose depot weights (Figures 7B and C and S6C and D and S7G). Further, cold-exposed SB-treated mice had robust visceral perigonadal beiging (Figure S7H and I). SMA fate mapping analyses of cold-exposed six-month old SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP SB-treated mice showed the formation of UCP1+ multilocular adipocytes from an RFP+ source that we did not detect in vehicle-treated littermates (Figure 7D). Of note, SB did not appear to alter classical interscapular brown adipose tissue as assessed by tissue weight, histology and mRNA expression of thermogenic genes (Figure S7G and J and data not shown). To evaluate if SB also had the same effect in “Young” mice, we administered vehicle or SB to two-month old male C57/BL6 mice for five days and randomized them to the cold. We found that both vehicle and SB treated mice had similar responses to the cold (Figure S7K-N). Taken together, SB appears to be a potent beiging agent in older animals by reversing beige progenitor senescence.

Figure 7. Inhibiting p38/MAPK in SMA cells stimulates cold-induced beiging.

(A-D) Schema- Six month old TM induced SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP male mice were administered vehicle or SB202190 (75 μg/mouse/day) for five consecutive days. Mice were randomized to room temperature or cold for seven days (A). (B) H&E staining. (C) UCP1 IHC. (D) SMA/RFP fluorescence fate mapping. (E-H) Schema- Six-month-old TM induced SMA-CreERT2 and SMA-CreERT2; PPARγfl/fl male mice were administered vehicle or SB (75 μg/mouse/day) for five days and subjected to room or cold temperatures for seven days. (G) H&E staining. (H) UCP1 IHC. Scale bar = 200 μm.

To further probe the possibility that the effects of SB in promoting cold-induced beige formation and cold-induced metabolic improvement were due to the SMA+ beige progenitor lineage, we turned to a strain of mice, SMA-CreERT2; PPARγfl/fl, in which the SMA+ progenitors have disrupted beiging potential (Figure 7E) (Berry et al., 2016). We induced conditional PPARγ deletion in six-month-old male mice by administering TM. Mice were randomized to vehicle or SB and then to seven days of room or cold temperatures (Figure 7F). The four groups (control + vehicle, control + SB, SMA-PPARγ mutant + vehicle, and SMA-PPARγ mutant + SB) of mice maintained at room temperature had equivalent body temperature and adiposity (Figure S7O). Notably, the progenitor mutation blocked the ability of SB to restore cold-induced beiging and cold-induced metabolic improvement (Figures 7G and H and S7O and S7P). We also observed similar beiging results in isolated total SV cells based on the inability of SB to promote beiging of SMA PPARγ deficient cells or any other compensatory cells (Figure 7SQ and R). Taken together, these data support the notion that systemic SB therapy can decrease p38 phosphorylation and its activity specifically in SMA+ beige progenitors, which in turn reverses the senescence-like phenotype and resuscitates cold-induced beige adipocyte formation and cold-induced metabolic benefits.

DISCUSSION

Cold temperatures can stimulate formation of energy burning beige adipocytes and can activate metabolism to increase energy expenditure; thus this phenomenon has attracted therapeutic attention because of its potential benefit for obesity, diabetes and their associated metabolic sequelae (Kajimura and Saito, 2014; Saito, 2013; Yoneshiro et al., 2013). An obstacle to clinical application is that cold temperatures do not induce beige/brown adipose tissue in older animals or humans; yet, it is with advancing age that people develop dwindling energy expenditure, accumulating adiposity, and higher incidence of diabetes (Yoneshiro et al., 2011). Similar to other processes that deteriorate in an age-related manner, the failure to form cold-induced beige adipocytes may be due to cellular aging and senescence of beige progenitors (Long et al., 2014). Here we found that beige progenitors acquire an age-related-senescence-like phenotype during aging, which prevents them from forming beige adipocytes in response to the cold. We found that genetically or pharmacologically inducing senescence was sufficient to block cold-induced beiging. Conversely, genetically or pharmacologically reversing cellular aging and senescence was able to revitalize “Old” beige progenitors to promote beige adipocyte formation and improved overall metabolic function. We further found that beige progenitors from human samples also display cellular aging and beiging failure phenotypes and that these can be rescued by targeting the p38 pathway. These data resonate with recent observations that senescence inhibitory drugs can blunt age-induced skeletal muscle dysfunction, stimulating muscle satellite stem cell renewal and skeletal muscle regeneration (Bernet et al., 2014; Cosgrove et al., 2014). In addition these studies echo with recent reports showing that targeting and/or eliminating senescent cells could rejuvenate tissue function and extend lifespan (Xu et al., 2015; Yosef et al., 2016). For example, studies using navitoclax, a senolytic a class of senotherapueties that selectively induces senescent cell death, restores stem cell health and function (Chang et al., 2016). Thus in adipose tissue, pharmacologic or other approaches to senescence modulation may also be therapeutic avenues to exploit the potential of the beige phenomenon to improve metabolic health.

Complementary functional tests lend credence to the notion that age-dependent beige progenitor dysfunction might, in part, be attributed to cellular senescence. For example, in vivo and in vitro tests, through genetic (TRE-p21) and pharmacologic (PD033291) means, indicated that senescence was sufficient to block cold-inducible beige adipocyte formation in young mice. Reciprocal tests through genetic (Ink4/Arf deletion) and pharmacological (SB202190) means blunted senescence in older animals and restored cold-induced beiging and metabolic benefits. Our studies also show that inhibiting the p38/MAPK pathway using SB202190 appears to promote the ability of beige progenitors to form cold-induced beige adipocytes. Interestingly, studies performed by Collins and colleagues found that blocking p38/MAPK prevents the formation of brown and beige adipocytes in response to β3-adrenergic stimulation (Bordicchia et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2004; Robidoux et al., 2005). Our studies differ in that we are not continuously treating with the p38/MAPK inhibitor, rather we have primed the cells with SB202190 and then exposed the animals to cold (not the β3 agonist, CL316,243). These slight variations could have different physiological and cellular consequences. These opposing observations raise the interesting notion that cold and β3-adregenic agonist may target different cell types and/or cellular pathways. Granneman and colleagues have already suggested that PDGFRα+ cells act as a progenitor cell source for β3-adrenergic signaling, but not for cold exposure (Lee et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2012) thus opening an area of exciting new research potential.

Our studies also highlight the metabolic relevance of rodent beige adipocytes in regards to whole body metabolism. For example, “Old” mice, which have reduced beiging potential in response to the cold, have reduced ability to take up sera glucose and free fatty acids into tissues. Also, “Old” mice have a dampened ability to reduce white adipose depot adiposity whereas “Young” animals show significant adiposity loss. This observation of reduced adiposity and glucose uptake appears to be primarily due to the loss of beige adipocytes but other tissues and age-related events could also be contributing metabolic factors. Our genetic manipulation and pharmacological administration studies, targeting anti-aging and senescence pathways, demonstrated a rejuvenation of beige adipocyte formation and restored metabolism in old mice. For instance, treating “Old” mice with SB202190 and subsequently cold exposing these mice for seven days increased beige adipocyte formation which appeared to be the root of increased glucose uptake and reduced adiposity. Furthermore, treating aged-human SV cells with SB restored their beiging potential suggesting a direct translational application of aging obese patients. The role of beige adipocytes in human metabolism suggests that in some instances beige adipocyte formation increases glucose and free fatty acid uptake (Blondin et al., 2014; Chondronikola et al., 2014; Chondronikola et al., 2016; Cypess et al., 2015). Collectively, the data suggest, in murine models and human SV cells, beige adipocytes contribute a considerable role in energy metabolism, in the absence of changes to classical interscapular brown adipose tissue.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

All animals were maintained under the guidelines of the UT Southwestern Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee according to NIH guidelines. Mice were housed in a 12:12 light:dark cycle and chow and water were provided ad libitum. C57/Bl6, PPARγfl/fl, and R26RRFP mice were obtained in the Jackson Laboratory. Dr. Eric Olson generously provided UCP1-CreERT2 and Ink4a/Arffl/fl mice. SMA-CreERT2 mice were generously provided by Dr. Pierre Chambon. SMA-rtTA mice were generously provided by Dr. Beverly Rothermel. Cre recombination was induced by administering tamoxifen dissolved in sunflower oil (Sigma, 100 mg/Kg interperitoneal injection) on 2 consecutive days. rtTA activation was induced by Doxycycline (0.5mg/ml in 1% sucrose) provided in the drinking water and protected from light, and it was changed every 2-3 days. For cold experiments mice were placed in a 6°C cold room or maintained at room temperature (23°C) for seven days.

Cell Culture

Isolated mouse SV cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Beige adipogenesis was induced by treating confluent cells with DMEM containing 10% FBS, insulin (0.5 μg/ml), dexamethasone (5 μM), isobutylmethylxanthine (0.5 mM), rosiglitazone (1 μM), and T3 (2 nM). To induce thermogenic genes, cells were treated with 10 μM forskolin for 4 hours and harvested to collect mRNA (Wu et al., 2012). Oil Red O staining and triglyceride accumulation were performed as previously described and using a kit from ZenBio (Berry and Noy, 2009; Berry et al., 2010). For Dox treatment, cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, and with or without Dox at a concentration of 50 ng/ml. For growth assays, 103 SV or RFP+ cells were counted, plated and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were counted every 24 hours using a hemocytometer and trypan blue was used to exclude dead cells.

Human Cell Culture

Isolated human adipose SV cells were purchased from ZenBio (Research Triangle Park, North Carolina). Cells were from young (23.5 yrs. ± 3.87) and old (49.33 yrs. ± 6.02) non-obese BMI (23.43 ± 4.32, Young; 24.67 ± 2.61, Old) female patients, isolated from the abdomen and hip. Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and were only passaged once prior to use. Four cell lines from each group were used and data are expressed as means ±S.E.M.

Pharmacological administration

PD0332991 (PD) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and dissolved in DMSO. Administration solution was dissolved further in water (DMSO ~5%). PD was administered at one dose (250 μg/mouse) for five consecutive days by interperitoneal injections (IP). SB202190 (SB) was purchased from Cayman Chemicals and dissolved in DMSO. Administration solution was dissolved further in water (DMSO ~5%). SB was administered at one dose (75 μg/mouse) for five consecutive days by IP.

Flow Cytometry and Sorting

SV cells were isolated and washed, centrifuged at 800g for 5min, and analyzed with a FACS analyzer or sorted with a BD FACS Aria operated by the UT Southwestern Flow Cytometry Core. Data analysis was performed using BD FACS Diva software. For RFP+ sorting, live SV cells from young (2-month) and old mice (6-month) SMA-CreERT2; R26RRFP mice were stained with propidium iodide (PI, 1mg/ml) to exclude dead cells and sorted based on native fluorescence (RFP). The SV cells from control mice were used to determine background fluorescence levels. The dissociated SV cells were also analyzed for senescence-associated markers by flow cytometry. Briefly, SV cells were incubated with primary antibodies on ice for 30 minutes and then washed twice with the staining buffer and incubated with cy5 donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody for another 30 minutes on ice before flow cytometric analysis. Primary antibodies include: rabbit-anti-p15/p16 (1:50, Santa Cruz), rabbit-anti-phosphor-p38 or total MAPK (1:200, Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-p21 (1:200, Cell Signaling), and the proliferative marker rabbit-anti-Ki67 (1:200, Vector labs).

Histology

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was carried out on paraffin sections using standard methods (Tang et al., 2008). Adipose tissues were fixed in formalin overnight, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned with a microtome at 5-8μm thickness. Immunostaining was performed in either paraffin sections or cryostat sections (5-8μm) of tissues freshly embedded in O.C.T. as previously described (Tang et al., 2008).

Metabolic Phenotyping Experiments

Temperature was monitored daily using a rectal probe (Physitemp). The probe was lubricated with glycerol and was inserted 1.27 centimeters (1/2 inch) and temperature was measured when stabilized. Glucose uptake experiment: Jugular vein catheters were surgically implanted in mice using previously described procedures (Hill et al., 2010) 14 days before exposure too cold for seven days. On the day of study (end of cold exposure), after a 4 hour fast, mice were injected with a bolus of 13 uCi of 14C 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) in the jugular vein catheter. Blood samples (20-25ul) were then taken at t = 2, 10, 17, and 25 min post-injection. At t = 25 min post-injection, mice were euthanized and tissues were collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Previously described procedures and calculations were used to determine plasma and tissue radioactivity and measure tissue-specific glucose uptake (Berglund et al., 2012; Hill et al., 2010).

Other Experimental Procedures

Generation of TRE-p21 mouse model, senescence activated βgal staining, metabolic phenotyping experiments, stromal vascular fraction isolation, qPCR, and histological staining are described in Supplemental Information.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was assessed by two-tailed Student's t test or one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc comparisons using the Bonferroni post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are means and error bars are expressed as ± SEM. All experiments were performed on 2-3 independent cohorts with a minimum of 3 mice/group. Experiments were performed on male mice at denoted ages. No mice were excluded from the study unless visible fight wounds were observed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease grants (R01 DK066556, R01 DK064261 and R01 DK088220) to JMG. DCB is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease grant K01 DK109027. JMG is a co-founder and shareholder of Reata Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

DCB, YJ conceived, designed, and performed experiments. DCB, YJ, and JMG analyzed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. RWA and MK developed the TRE-p21 transgenic mouse line. ELC, AU, DR and EDB performed radiolabel glucose uptake experiments and analysis. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Berglund ED, Vianna CR, Donato J, Jr., Kim MH, Chuang JC, Lee CE, Lauzon DA, Lin P, Brule LJ, Scott MM, et al. Direct leptin action on POMC neurons regulates glucose homeostasis and hepatic insulin sensitivity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1000–1009. doi: 10.1172/JCI59816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernet JD, Doles JD, Hall JK, Kelly Tanaka K, Carter TA, Olwin BB. p38 MAPK signaling underlies a cell-autonomous loss of stem cell self-renewal in skeletal muscle of aged mice. Nat Med. 2014;20:265–271. doi: 10.1038/nm.3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DC, Jiang Y, Graff JM. Mouse strains to study cold-inducible beige progenitors and beige adipocyte formation and function. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10184. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DC, Noy N. All-trans-retinoic acid represses obesity and insulin resistance by activating both peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor beta/delta and retinoic acid receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3286–3296. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01742-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DC, Soltanian H, Noy N. Repression of cellular retinoic acid-binding protein II during adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15324–15332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin DP, Labbe SM, Christian Tingelstad H, Noll C, Kunach M, Phoenix S, Guerin B, Turcotte EE, Carpentier AC, Richard D, et al. Increased brown adipose tissue oxidative capacity in cold-acclimated humans. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014:jc20133901. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordicchia M, Liu D, Amri EZ, Ailhaud G, Dessi-Fulgheri P, Zhang C, Takahashi N, Sarzani R, Collins S. Cardiac natriuretic peptides act via p38 MAPK to induce the brown fat thermogenic program in mouse and human adipocytes. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1022–1036. doi: 10.1172/JCI59701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annual review of physiology. 2013;75:685–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Daniel KW, Robidoux J, Puigserver P, Medvedev AV, Bai X, Floering LM, Spiegelman BM, Collins S. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is the central regulator of cyclic AMP-dependent transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein 1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3057–3067. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.3057-3067.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Wang Y, Shao L, Laberge RM, Demaria M, Campisi J, Janakiraman K, Sharpless NE, Ding S, Feng W, et al. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat Med. 2016;22:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nm.4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Cypess AM, Chen YC, Palmer M, Kolodny G, Kahn CR, Kwong KK. Measurement of human brown adipose tissue volume and activity using anatomic MR imaging and functional MR imaging. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2013;54:1584–1587. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.117275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T, Rodrigues N, Shen H, Yang Y, Dombkowski D, Sykes M, Scadden DT. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science. 2000;287:1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chondronikola M, Volpi E, Borsheim E, Porter C, Annamalai P, Enerback S, Lidell ME, Saraf MK, Labbe SM, Hurren NM, et al. Brown adipose tissue improves whole-body glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes. 2014;63:4089–4099. doi: 10.2337/db14-0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chondronikola M, Volpi E, Borsheim E, Porter C, Saraf MK, Annamalai P, Yfanti C, Chao T, Wong D, Shinoda K, et al. Brown Adipose Tissue Activation Is Linked to Distinct Systemic Effects on Lipid Metabolism in Humans. Cell metabolism. 2016;23:1200–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove BD, Gilbert PM, Porpiglia E, Mourkioti F, Lee SP, Corbel SY, Llewellyn ME, Delp SL, Blau HM. Rejuvenation of the muscle stem cell population restores strength to injured aged muscles. Nat Med. 2014;20:255–264. doi: 10.1038/nm.3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess AM, Weiner LS, Roberts-Toler C, Franquet Elia E, Kessler SH, Kahn PA, English J, Chatman K, Trauger SA, Doria A, et al. Activation of human brown adipose tissue by a beta3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Cell metabolism. 2015;21:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa M, Porras DP, Perry CG, Seale P, Scime A. p107 Is a Crucial Regulator for Determining the Adipocyte Lineage Fate Choices of Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1323–1336. doi: 10.1002/stem.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson MA, Tap WD, Keohan ML, D'Angelo SP, Gounder MM, Antonescu CR, Landa J, Qin LX, Rathbone DD, Condy MM, et al. Phase II trial of the CDK4 inhibitor PD0332991 in patients with advanced CDK4-amplified well-differentiated or dedifferentiated liposarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2024–2028. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.5476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani M, Himms-Hagen J. Appearance of brown adipocytes in white adipose tissue during CL 316,243-induced reversal of obesity and diabetes in Zucker fa/fa rats. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 1997;21:465–475. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golozoubova V, Hohtola E, Matthias A, Jacobsson A, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Only UCP1 can mediate adaptive nonshivering thermogenesis in the cold. FASEB J. 2001;15:2048–2050. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0536fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallenborg P, Feddersen S, Madsen L, Kristiansen K. The tumor suppressors pRB and p53 as regulators of adipocyte differentiation and function. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:235–246. doi: 10.1517/14712590802680141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JB, Jorgensen C, Petersen RK, Hallenborg P, De Matteis R, Boye HA, Petrovic N, Enerback S, Nedergaard J, Cinti S, et al. Retinoblastoma protein functions as a molecular switch determining white versus brown adipocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4112–4117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0301964101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JW, Elias CF, Fukuda M, Williams KW, Berglund ED, Holland WL, Cho YR, Chuang JC, Xu Y, Choi M, et al. Direct insulin and leptin action on pro opiomelanocortin neurons is required for normal glucose homeostasis and fertility. Cell Metab. 2010;11:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimura S, Saito M. A new era in brown adipose tissue biology: molecular control of brown fat development and energy homeostasis. Annual review of physiology. 2014;76:225–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanigan F, Geraghty JG, Bracken AP. Transcriptional regulation of cellular senescence. Oncogene. 2011;30:2901–2911. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Petkova AP, Konkar AA, Granneman JG. Cellular origins of cold-induced brown adipocytes in adult mice. FASEB J. 2015;29:286–299. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-263038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Petkova AP, Mottillo EP, Granneman JG. In vivo identification of bipotential adipocyte progenitors recruited by beta3-adrenoceptor activation and high-fat feeding. Cell Metab. 2012;15:480–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JZ, Svensson KJ, Tsai L, Zeng X, Roh HC, Kong X, Rao RR, Lou J, Lokurkar I, Baur W, et al. A Smooth Muscle-Like Origin for Beige Adipocytes. Cell Metab. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud K, Solomon DA, Oermann E, Kim JS, Zhong WZ, Prados MD, Ozawa T, James CD, Waldman T. Pharmacologic inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 arrests the growth of glioblastoma multiforme intracranial xenografts. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3228–3238. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert M, Eick D. Analysis of cell cycle arrest in adipocyte differentiation. Oncogene. 1999;18:459–466. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robidoux J, Cao W, Quan H, Daniel KW, Moukdar F, Bai X, Floering LM, Collins S. Selective activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase 3 and p38alpha MAP kinase is essential for cyclic AMP-dependent UCP1 expression in adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5466–5479. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5466-5479.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers NH, Landa A, Park S, Smith RG. Aging leads to a programmed loss of brown adipocytes in murine subcutaneous white adipose tissue. Aging Cell. 2012;11:1074–1083. doi: 10.1111/acel.12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M. Brown adipose tissue as a regulator of energy expenditure and body fat in humans. Diabetes & metabolism journal. 2013;37:22–29. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2013.37.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signer RA, Morrison SJ. Mechanisms that regulate stem cell aging and life span. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa-Victor P, Gutarra S, Garcia-Prat L, Rodriguez-Ubreva J, Ortet L, Ruiz-Bonilla V, Jardi M, Ballestar E, Gonzalez S, Serrano AL, et al. Geriatric muscle stem cells switch reversible quiescence into senescence. Nature. 2014;506:316–321. doi: 10.1038/nature13013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Zeve D, Suh JM, Bosnakovski D, Kyba M, Hammer RE, Tallquist MD, Graff JM. White fat progenitor cells reside in the adipose vasculature. Science. 2008;322:583–586. doi: 10.1126/science.1156232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, van Deursen J, Campisi J, Kirkland JL. Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype: therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:966–972. doi: 10.1172/JCI64098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Lans AA, Hoeks J, Brans B, Vijgen GH, Visser MG, Vosselman MJ, Hansen J, Jorgensen JA, Wu J, Mottaghy FM, et al. Cold acclimation recruits human brown fat and increases nonshivering thermogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3395–3403. doi: 10.1172/JCI68993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Bostrom P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, Khandekar M, Virtanen KA, Nuutila P, Schaart G, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Palmer AK, Ding H, Weivoda MM, Pirtskhalava T, White TA, Sepe A, Johnson KO, Stout MB, Giorgadze N, et al. Targeting senescent cells enhances adipogenesis and metabolic function in old age. eLife. 2015;4:e12997. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Kayahara T, Kameya T, Kawai Y, Iwanaga T, Saito M. Recruited brown adipose tissue as an antiobesity agent in humans. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3404–3408. doi: 10.1172/JCI67803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Kameya T, Kawai Y, Miyagawa M, Tsujisaki M, Saito M. Age-related decrease in cold-activated brown adipose tissue and accumulation of body fat in healthy humans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1755–1760. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef R, Pilpel N, Tokarsky-Amiel R, Biran A, Ovadya Y, Cohen S, Vadai E, Dassa L, Shahar E, Condiotti R, et al. Directed elimination of senescent cells by inhibition of BCL-W and BCL-XL. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11190. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young P, Arch JR, Ashwell M. Brown adipose tissue in the parametrial fat pad of the mouse. FEBS Lett. 1984;167:10–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80822-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.