Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that higher financial and health literacy are associated with better cognitive health in 755 older persons who completed a literacy measure (M=67.9, SD=14.5) and then had annual clinical evaluations for a mean of 3.4 years. In proportional hazards models, higher literacy was associated with decreased risk of developing incident Alzheimer’s disease (n=68) and results were similar for financial and health literacy subscales and after adjustment for potential confounders. In mixed-effects models, higher literacy was related to higher baseline level of cognition and reduced cognitive decline in multiple domains. Among the 602 persons without any cognitive impairment at baseline, higher literacy was associated with a reduced rate of cognitive decline and risk of developing incident mild cognitive impairment (n=142). The results suggest that higher levels of financial and health literacy are associated with maintenance of cognitive health in old age.

Keywords: financial literacy, health literacy, cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment

Introduction

Literacy, broadly defined as the ability to use written materials to function effectively in society (Kutner, Greenberg, Jin, & Paulsen, 2003), is a critical determinant of health and well-being across the lifespan. Financial and health literacy are particularly important in old age, as individuals are confronted by complex economic and medical issues. Unfortunately, many older persons have limited knowledge in these domains (Baker, Gazmararian, Sudano, & Patterson, 2000; Saha, 2006; Sudore, Mehta, et al., 2006; Wolf, Gazmararian, & Baker, 2005) and lower levels of health (Baker et al., 2002; Baker, Wolf, Feinglass, & Thompson, 2008; Baker et al., 2007; Schillenger et al., 2002; Scott, Gazmararian, Williams, & Baker, 2002; Sudore, Yaffe, et al., 2006; Wolf et al., 2005) and financial (Agarwal, Driscoll, Gabaix, & Laibson, 2009; Bennett, Boyle, James, & Bennett, 2012; Condelli, 2006; Lusardi & Mitchell, 2007a and b) literacy have been associated with adverse health and economic outcomes. Notably, however, the relation of financial and health literacy to late-life cognitive health has not been extensively investigated. A recent study linked low reading literacy to increased risk of dementia (Kaup et al., 2014). However, it is not clear whether this finding is due to the association of literacy with level of cognitive function or rate of cognitive decline, or whether it generalizes to financial or health literacy.

In this study, we test the hypothesis that higher literacy is associated with lower incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and less rapid cognitive decline. Participants are community-dwelling older people who completed measures of literacy at study baseline and then underwent annual evaluations to measure cognitive outcomes. The hypothesized association of literacy with cognitive outcomes was tested in a series of proportional hazards models (for incident events) and mixed-effects models (for continuous outcomes).

Methods

Participants

These analyses are based on persons participating in the Rush Memory and Aging Project, an ongoing longitudinal cohort study that began in 1997 (Bennett et al., 2005; Bennett et al, 2012). Participants are from the Chicago metropolitan region. They were recruited from retirement communities, subsidized senior housing, social service agencies, and local churches. After a presentation about the project, study staff had more detailed discussions with interested individuals and obtained written informed consent. The project was approved by the institutional review board of Rush University Medical Center.

The present analyses are based on an ongoing study of decision making conducted on a subset of Rush Memory and Aging Project participants beginning in 2009. Of 1,021 persons in the parent study who were alive and eligible for the decision making substudy, 911 persons had completed the substudy baseline at the time of these analyses, the evaluation was pending in 67, and 43 (4.2%) had refused. We excluded 54 individuals with dementia and 3 with incomplete decision making data, leaving 854 persons eligible at baseline. There were 20 deaths before the first annual follow-up evaluation and 59 had been in the study less than one year, leaving 775 persons eligible for follow-up. Follow-up cognitive data were available on 773 individuals and follow-up clinical diagnostic data was available on 755 (because clinical diagnoses are rendered a few months after the date of the clinical evaluation). These 755 individuals had a mean age of 81.7 (SD=7.6) at study baseline and had completed a mean of 15.2 years of education (SD=3.0); and 76.6% were women. They had a mean at baseline of 28.3 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (SD=1.7) and 153 (20.3%) met criteria for mild cognitive impairment.

Clinical Classification

At study baseline and annually thereafter, participants had a uniform evaluation that included a structured medical history, neurological examination, and a battery of cognitive tests. Following each evaluation an experienced clinician, who was kept unaware of previously collected data, diagnosed dementia, AD, and MCI. Classification of dementia and AD was done using the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders criteria which require a history of cognitive decline and impairment in at least two cognitive domains one of which must be memory to meet criteria for AD (McKhann et al., 1984). Individuals who had impairment in one or more cognitive domains but did not meet dementia criteria were classified as having MCI, as described elsewhere (Bennett et al., 2002; Boyle et al., 2006).

Assessment of Literacy

Literacy was assessed with 32 items addressing financial and health information and ideas, as previously described (Bennett, Boyle, James, & Bennett, 2012; James, Boyle, Bennett, & Bennett, 2012; Boyle et al., 2013). Financial literacy was assessed with 23 questions adapted in part from the Health and Retirement Survey (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2007a and b) with simple arithmetic items to evaluate numeracy and question about financial concepts such as compound interest. There were another nine items assessing health literacy, including “questions on Medicare, following doctors’ prescription instructions, leading causes of death in older persons, and a question framing the same drug risk information in difference ways” ([page 532] James, Boyle, Bennett, & Bennett, 2012). Items, which were true/false or multiple choice, were scored as correct or incorrect. Scores for total literacy (32 items), financial literacy (23 items), and health literacy (9 items) were the percent of correct items. In previous research, the total literacy score has been shown to have adequate temporal stability (intraclass correlation over 1-year period = 0.75) and to be related to diverse health outcomes (Bennett et al., 2012; James et al., 2012; Boyle et al., 2013).

Assessment of Cognitive Function

Cognition was assessed with a battery of 19 performance tests administered in a session lasting approximately 1 hour. One aim of the testing was to support clinical classification. To this end, we developed an algorithm using educationally adjusted cutpoints on 11 tests to rate impairment in 5 broad cognitive domains (orientation, attention, memory, language, perception). A neuropsychologist reviewed the ratings and in the event of disagreement provided new ratings. A physician or nurse practitioner subsequently used these cognitive impairment ratings in clinical classification of MCI, dementia, and AD. Further information on the algorithm and clinical classification process is published elsewhere (Bennett et al., 2002; Bennett et al., 2006; Wilson, Boyle, Yang, James, & Bennett, 2015).

A second aim of the testing was to measure change in cognitive abilities. Two tests, the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) and Complex Ideational Material (Goodglass & Kaplan, 1983), were used diagnostically but not analytically. Supported by previous factor analyses in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (Wilson, Barnes, & Bennett, 2003; Wilson et al., 2005) and other cohorts (Wilson et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2009), the remaining 17 tests were grouped into 5 domains. There were 7 episodic memory measures; immediate and delayed recall of Logical Memory Story A (Wechsler, 1987) and the East Boston Story (Albert et al., 1991; Wilson et al., 2002), Word List Memory, Word List Recall, and Word List Recognition (Welsh et al., 1994; Wilson et al., 2002). Semantic memory was assessed with a 15-item short form of the Boston Naming Test, a 15-item word reading measure, and a verbal fluency measure in which category examples (i.e., animals, vegetables) are named in 60 second trials (Welsh et al., 1994; Wilson et al. 2002). Digit Span Forward, Digit Span Backward, and Digit Ordering assessed working memory (Wechsler, 1987; Wilson et al., 2002). Modified versions (Wilson et al., 2002) of Number Comparison (Ekstrom, French, Harman, & Kermen, 1976) and the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (Smith, 1982) assessed perceptual speed, and short forms (Wilson et al., 2002) of Judgment of Line Orientation (Benton, Sivan, Hamsher, Varney, & Spreen, 1994) and Standard Progressive Matrices (Raven, Court & Raven, 1992) assessed visuospatial ability. Raw scores on each measure were converted to z scores, using the baseline mean and standard deviation, and the z scores were averaged to yield composite measures of episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual speed, and visuospatial ability. We also formed a composite measure of global cognition based on all 17 tests. These composite measures can accommodate a wider range of performance than individual tests and thereby minimize floor and ceiling artifacts in longitudinal analyses. Further information on the individual tests and these composite measures is published elsewhere (Wilson et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2015).

Assessment of Other Covariates

Income at baseline was assessed with a show card listing eleven income categories. As part of the medical history at baseline, participants were asked about seven common chronic conditions: cancer, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disorder, and head injury. The number of conditions reported was used as a measure of chronic illness (Wilson, Mendes de Leon, et al., 2002).

Statistical Analysis

All models were adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education. The relation of baseline literacy to incident AD was analyzed in proportional hazards models (Cox, 1972). Separate models were constructed for the 3 literacy measures and the models were repeated with terms added for chronic illness and income. Similar models were constructed to test the relation of literacy to incident MCI.

Mixed-effects models (Laird & Ware, 1982) were used to characterize change in cognitive function and to test the association of literacy with cognitive function at baseline and the annual rate of cognitive change. Each model included a term for time in years since baseline, literacy, and the interaction of literacy and time (plus terms for demographic variables and their interactions with time). The composite measure of global cognition was the outcome in initial models and subsequent models used composite measures of specific cognitive domains as outcomes. We first conducted analyses in all participants followed by analyses excluding persons with MCI at baseline.

RESULTS

Literacy and Alzheimer’s disease

At baseline, total literacy scores ranged from a low of 24.2 to a high of 100 (M=67.9, SD = 14.5) with similar distributions in the financial (M=73.4, SD=15.8) and health (M=62.5, SD=18.4) subscales. Higher literacy was associated with younger age (r=-0.33, p<0.001) and higher level of education (r=0.39, p<0.001). Men had higher literacy scores than women (72.4 vs 66.6, t[753]=4.7, p<0.001) which was due to better financial literacy (83.2 vs 70.4, t[336.6]=11.0, p=0.001) with no sex differences in health literacy (61.5 vs 62.8, t[753]=0.8, p=0.416).

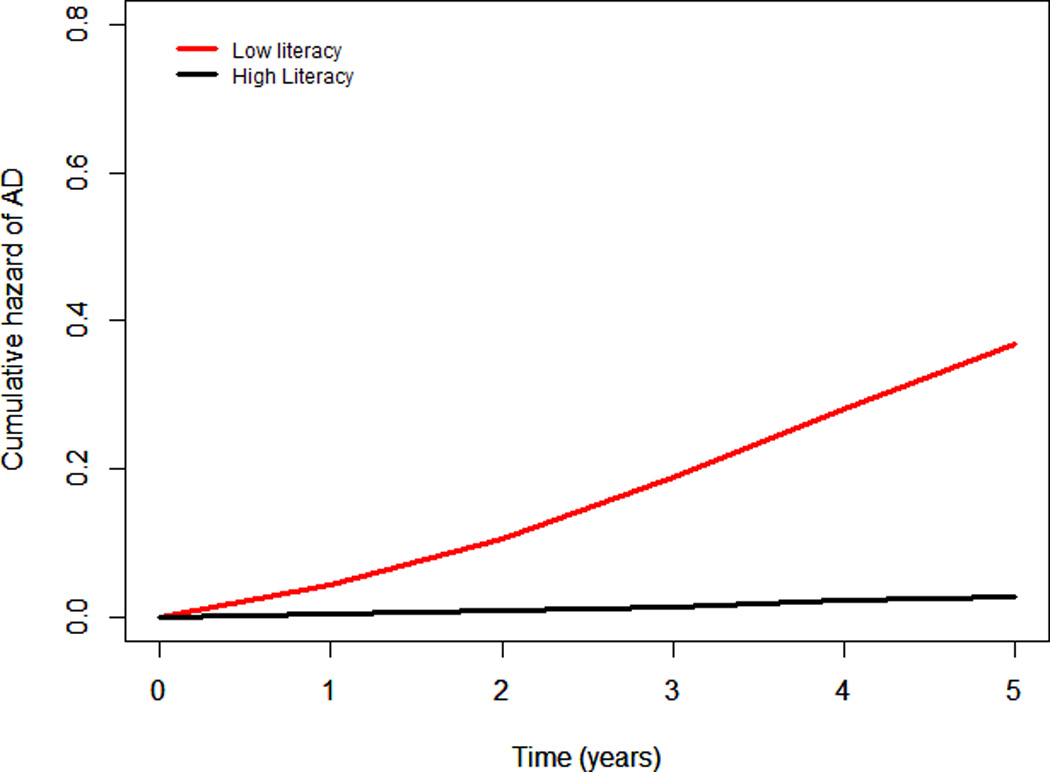

During a mean of 3.4 years of observation (SD=1.4), 68 persons (9.0%) developed incident AD. As shown in Table 1, the incident AD subgroup was older than the subgroup that did not develop AD, and they had lower levels of literacy, income, and cognitive function. We tested for the hypothesized association of literacy with incident AD in a series of proportional hazards models. These and all subsequent analyses were adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education. In the initial model, higher total literacy score was associated with decreased risk of AD (hazard ratio [HR]=0.930, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.911, 0.949). With each additional point, risk was approximately 7% lower. As shown in Figure 1, which is based on this analysis, a typical participant with a high level of literacy (black line, score = 85.7, 90th percentile) was much less likely to develop AD than a participant with low literacy (red line, score = 48.1, 10th percentile).

Table 1.

Baseline comparison of those who developed dementia with those who remained unaffected

| Characteristic | Incident AD (n=68) | Unaffected (n=687) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 85.8 | 81.3 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Education | 14.7 (2.9) | 15.2 (3.0) | 0.124 |

| Women, % | 80.9 | 76.1 | 0.377 |

| Total literacy | 54.5 (12.7) | 69.3 (14.0) | <0.001 |

| Financial literacy | 61.7 (15.3) | 74.5 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| Health literacy | 47.2 (16.2) | 64.0 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Chronic conditions | 0.68 (0.87) | 1.00 (1.04) | 0.014 |

| Income level | 6.19 (2.43) | 7.22 (2.40) | 0.003 |

| MMSE | 26.5 (2.2) | 28.4 (1.6) | <0.001 |

Note. Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise indicated. MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Figure 1.

Cumulative hazard of developing Alzheimer’s disease in persons with high (black line, 90th percentile) versus low (red line, 10th percentile) literacy, adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education.

In subsequent models, higher financial (HR:0.953), 95% CI:0.937, 0.970) and health (HR:0.955, 95% CI:0.942,0.969) literacy were each associated with lower risk of incident AD. Those who developed AD reported fewer chronic medical conditions and lower income than unaffected persons (Table 1), but results were comparable after adjustment for these factors (HR for total literacy: 0.929, 95% CI:0.908, 0.952).

Because a previous study found that the association of literacy with risk of dementia varied by apolipoprotein E geneotype (Kaup et al., 2014), we repeated the initial model with terms added for possession of an є4 allele (present in 158 persons [20.9%]) and its interaction with literacy. There was no interaction (estimate=0.014, SE=0.015, p=0.330).

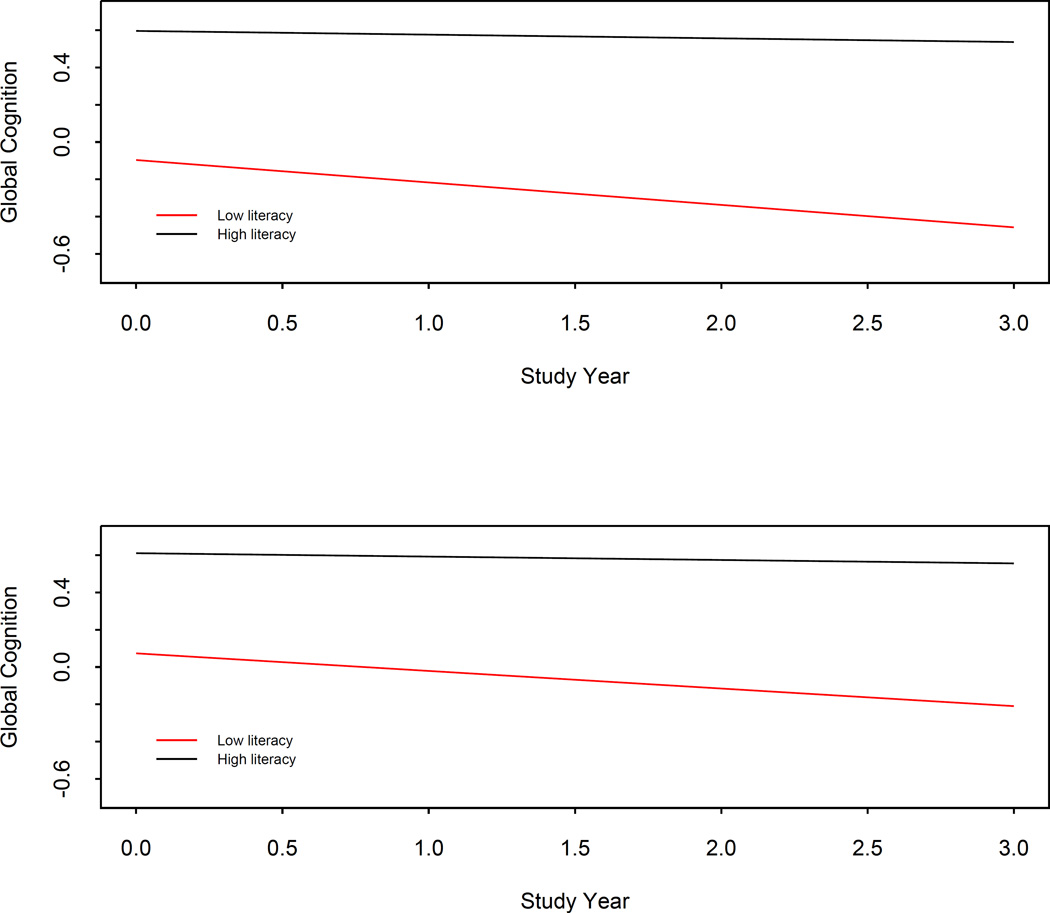

To determine whether literacy was related to AD due to an association with level of cognitive function, rate of cognitive decline, or both, we examined the relation of literacy to cognitive aging trajectories in a series of mixed-effects models. To capitalize on all cognitive data, the outcome in initial analyses was a composite measure global cognition based on 17 individual tests (baseline mean=0.234, SD=0.521). The global cognitive score declined a mean of 0.249-unit per year (SE=0.028, p<0.001). Higher total literacy was associated with a higher initial level of global cognition (estimate=0.018, SE=0.001, p<0.001) and a slower rate of cognitive decline (estimate=0.003, SE=0.0004, p<0.001). As shown in the upper portion of Figure 2, which is based on this analysis, the predicted annual rate of decline in a person with high literacy (black line, 90th percentile) was slightly slower than the predicted rate in a person with low literacy (red line, 10th percentile).

Figure 2.

Predicted 3-year paths of change in global cognition in persons with high (black line, 90th percentile) versus low (red line, 10th percentile) literacy, with the baseline mild cognitive impairment subgroup included (upper portion) or excluded (lower portion), adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education.

To see if literacy was more strongly related to some cognitive domains than others, we conducted analyses using composite measures of five different cognitive domains. In these analyses, higher literacy was associated with higher baseline level of function and slower rate of decline in each cognitive domain (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relation of total literacy to baseline level and annual rate of change in different cognitive domains in those without dementia at baseline

| Cognitive domain | Model term | Estimate | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic memory | Time | −0.287 | 0.037 | <0.001 |

| Literacy | 0.019 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.003 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Semantic memory | Time | −0.222 | 0.029 | <0.001 |

| Literacy | 0.019 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.002 | 0.0004 | <0.001 | |

| Working memory | Time | −0.139 | 0.034 | <0.001 |

| Literacy | 0.018 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.006 | |

| Perceptual speed | Time | −0.236 | 0.031 | <0.001 |

| Literacy | 0.019 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.002 | 0.0004 | <0.001 | |

| Visuospatial ability | Time | −0.151 | 0.034 | <0.001 |

| Literacy | 0.016 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.002 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

Note. From 5 separate mixed-effects models adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education. SE, standard error.

To adjust for socioeconomic heterogeneity not captured by education, we repeated the previous analysis with terms for income and chronic medical conditions. Results were essentially unchanged (data not shown).

Literacy and mild cognitive impairment

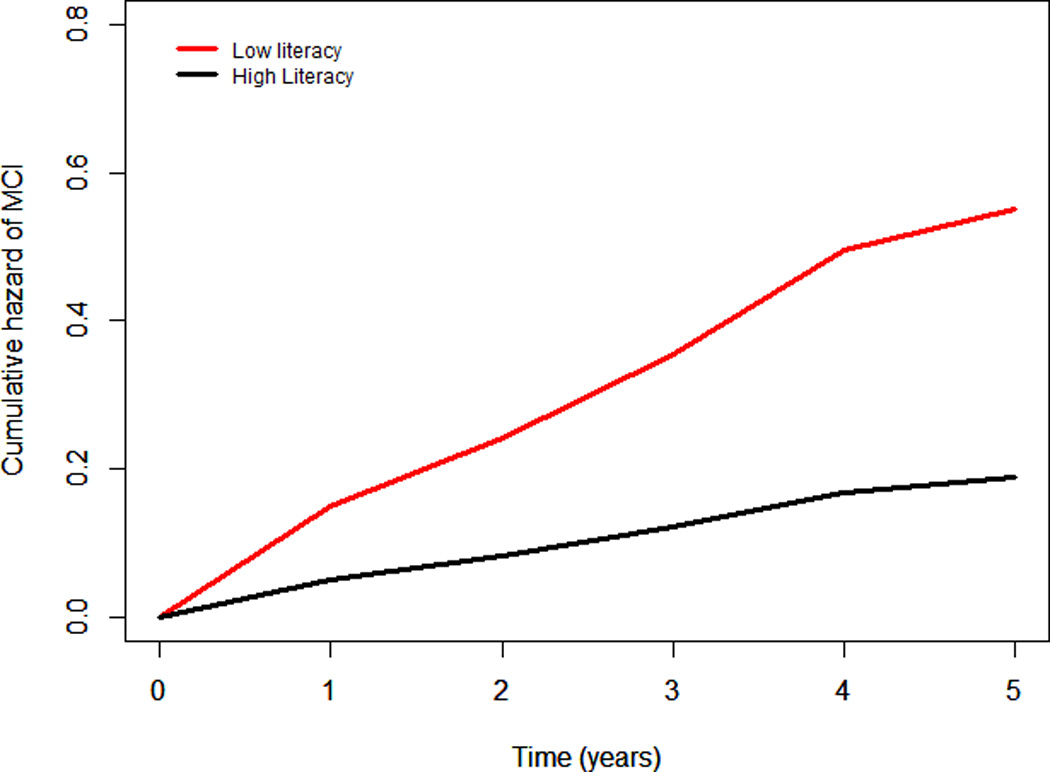

Because cognitive dysfunction may impair literacy (Boyle et al., 2013), we conducted additional analyses after excluding the 153 participants who had MCI at baseline. In the remaining 602 persons with no cognitive impairment at baseline (age M=80.9 SD=7.8; education M=15.2, SD=3.0; 77.6% women), 142 (23.6%) developed MCI. In a proportional hazards model, total literacy was associated with reduced risk of developing MCI (HR:0.966, 95% CI:0.952, 0.980).

As shown in Figure 3, which is based on this model, a typical participant with a high level of literacy (black line, 90th percentile) was substantially less likely to develop MCI compared to a typical participant with low literacy (red line, 10th percentile). Results were similar for financial (estimated relation to intercept = 0.014, SE=0.001, p<0.001; estimated relation to slope=0.002, SE=0.0004, p<0.001) and health (estimated relation to intercept=0.011, SE=0.001, p<0.001; estimated relation to slope =0.002, SE=0.0003, p<0.001) literacy subscores.

Figure 3.

Cumulative hazard of developing mild cognitive impairment in persons with high (black line, 90th percentile) versus low (red line, 10th percentile) literacy, adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education.

In a mixed-effects model, higher total literacy was related to higher global cognition at baseline (estimate=0.014, SE=0.001, p<0.001) and slower annual global cognitive decline (estimate = 0.002, SE=0.0004, p<0.001). The lower portion of Figure 2 shows the predicted trajectories for persons with high (black line, 90th percentile) versus low (red line, 10th percentile) literacy. As shown in Table 3, higher total literacy was related to slower decline in episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, and perceptual speed but was unrelated to decline in visuospatial ability.

Table 3.

Relation of total literacy to baseline level and annual rate of change in different cognitive domains in those without impairment at baseline

| Cognitive domain | Model term | Estimate | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic memory | Time | −0.201 | 0.041 | <0.001 |

| Literacy | 0.012 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.002 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Semantic memory | Time | −0.133 | 0.029 | <0.001 |

| Literacy | 0.015 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.001 | 0.0004 | 0.002 | |

| Working memory | Time | −0.125 | 0.040 | 0.002 |

| Literacy | 0.016 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.025 | |

| Perceptual speed | Time | −0.186 | 0.035 | <0.001 |

| Literacy | 0.015 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Visuospatial ability | Time | −0.072 | 0.038 | 0.059 |

| Literacy | 0.016 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Literacy x time | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.268 |

Note. From 5 separate mixed-effects models adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education. SE, standard error.

DISCUSSION

We assessed financial and health literacy in a group of more than 750 older persons without dementia at study baseline and then evaluated their cognitive health at annual intervals for a mean of 3.4 years. Persons with higher levels of literacy were substantially less likely to develop MCI and AD than less literate persons. The findings suggest higher levels of financial and health literacy may help delay the development of dementia in old age.

A recent study reported that low reading literacy, assessed with a word reading test, predicted higher subsequent risk of dementia in those without a copy of the apolipoprotein E є4 allele (Kaup et al., 2014). The current analyses extend these findings in several ways. First, these data suggest that literacy in domains other than reading is associated with risk of dementia. Although financial and health literacy are critically important for optimizing health and well being in old age, to our knowledge, financial and health literacy have not previously been shown to predict late-life cognitive outcomes. Second, we showed that literacy also predicts development of MCI which typically precedes dementia by several years (Wilson et al., 2011). This is important because it indicates that literacy is associated with the initial development of cognitive impairment and that the association is not driven by a subset with severe cognitive dysfunction. Third, the current results suggest that the association of literacy with dementia is independent of apolipoprotein E genotype.

Higher level of literacy was associated with higher level of cognitive function, consistent with prior research (Baker, Wolf, Feinglass, & Thompson, 2008; Kaup et al., 2014). A novel finding was that after accounting for the cross-sectional literacy-cognition correlation, higher level of literacy predicted slower decline in multiple cognitive domains. That is, those with higher levels of literacy not only begin old age with a higher level of ability than less literate individuals but they also experience less rapid cognitive decline. Further, the association of literacy with late-life cognitive health was not explained by indicators of socioeconomic status such as education and income.

The basis of the relationship between literacy and cognition is uncertain. Cognitive decline (Boyle et al., 2013) and dementia related pathology (Wilson et al., 2010) can impair literacy. Therefore, the association is probably reciprocal and its strength is likely due in part to low literacy being a very early consequence of even subtle cognitive changes due to underlying pathology. However, that literacy among cognitively healthy persons predicted subsequent cognitive outcomes suggests that literacy is at least partly a true risk factor. It is possible that higher financial and health literacy contribute to better health related behaviors and avoidance of adverse outcomes such as hospitalization which is associated with increased risk of cognitive decline (Wilson, Hebert, et al., 2012) and dementia (Ehlenhach et al., 2010). These results suggest that interventions designed to improve financial and health literacy may help preserve cognitive health in old age.

Strengths and limitations of these data should be noted. Clinical classification was based on a uniform clinical evaluation and widely accepted criteria, minimizing diagnostic misclassification. Results were consistent with binary and continuous cognitive outcomes suggesting that the findings are reliable. The main limitation is that results are based on a selected group of participants and so may not generalize to other groups. In addition, the observation that financial and health literacy had similar association with cognitive outcomes may not generalize to other aging outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants R01AG33678, R01AG34374, R01AG17917, and the Illinois Department of Public Health. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors thank the participants of the Rush Memory and Aging Project for their invaluable contributions. We thank Tracy Colvin, MPH, for study coordination, and John Gibbons, MS, and Greg Klein, MS, for data management, Alysha Kett, MS, for data analysis, and the staff of the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or other interests to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Agarwal S, Driscoll JC, Gabaix X, Laibson D. The age of reason: Financial decisions over the life-cycle and implication for regulation. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 2009:51–117. [Google Scholar]

- Albert M, Smith LA, Scherr PA, Taylor JO, Evans DA, Funkenstein HH. Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;57:167–178. doi: 10.3109/00207459109150691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:878–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Sudano J, Patterson M. The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. Journal of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences. 2000;55:S368–S374. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.s368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DW, Gazmararian JS, Williams MV, Scott T, Parker RM, Green D, Ren J, Peel J. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1278–1283. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA. Health literacy, cognitive abilities, and mortality among elderly persons. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:723–726. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0566-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA, Gazmararian JA, Huang J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:1503–1509. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JS, Boyle PA, James BD, Bennett DA. Correlates of Health and financial literacy in older adults without dementia. BMC Geriatrics. 2012;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Kelly JF, Fox JH, Cochran EJ, Arends D, Treinkman AD, Wilson RS. Decision rules guiding the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in two community-based cohort studies compared to standard practice in a clinic-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27:169–176. doi: 10.1159/000096129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Mendes de Leon CF, Wilson RS. The Rush Memory and Aging Project: study design and baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:163–175. doi: 10.1159/000087446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Current Alzheimer Research. 2012;9:646–663. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Evans DA, Beckett LA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Fox JH, Bach J. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:198–205. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Sivan AB, Hamsher K, de S, Varney NR, Spreen O. Contributions to neuropsychological assessment. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Segawa E, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Cognitive decline impairs financial and health literacy among community-based older persons without dementia. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28:614–624. doi: 10.1037/a0033103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Mild cognitive impairment: risk of Alzheimer’s disease and rate of cognitive decline. Neurology. 2006;67:441–445. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228244.10416.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condelli L. A review of the literature in adult numeracy: Research and conceptual issues. Washington, DC: The American Institutes or Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression models with life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, Haneuse SJ, Carson SS, Curtis JR, Larson EB. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:763–770. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom RB, French JW, Harman HH, Kermen D. Manual for kit of factor-referenced cognitive tests. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, Kaplan E. The assessment of aphasia and related disorders. 2nd. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- James BD, Boyle PA, Bennett JS, Bennett DA. The impact of health and financial literacy on decision making in community-based older adults. Gerontology. 2012;58:531–539. doi: 10.1159/000339094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaup AR, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, Satterfield S, Metti AL, Ayonayon HN, Yaffe K. Older adults with limited literacy are at increased risk for likely dementia. Journals of Gerontology Biological Sciences Medical Sciences, Series A. 2014;69:900–906. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of America’s adults: results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483) Washington: National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Laird N, Ware J. Random effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implication for financial education. Business Economics. 2007a;42:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Baby boomer retirement security: The roles of planning, financial literacy, and housing wealth. Journal of Monetary Economics. 2007b;54:205–224. [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JC, Court JH, Raven J. Manual for Raven’s progressive matrices and vocabulary: Standard Progressive Matrices. Oxford, England: Oxford Psychologists Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Saha S. Improving literacy as a means to reducing health disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:893–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, Wang F, Osmond D, Daher C, Bindman AB. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:475–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Medical Care. 2002;40:395–404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test manual-revised. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sudore RL, Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, Newman AB, Satterfield S, Yaffe K. Limited literacy in older people and disparities in health and healthcare access. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:770–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore RL, Yaffee K, Satterfield S, Harris TB, Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, Schillinger D. Limited literacy and mortality in the elderly: The health, aging, and body composition study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:806–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh KA, Butters N, Mohs RC, Beekly D, Edland S, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD), part V: a normative study of the neuropsychological battery. Neurology. 1994;44:609–614. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.4.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, Mendes de Leon CF, Evans DA. Biracial population study of mortality in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66:767–772. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Assessment of lifetime participation in cognitively stimulating activities. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2003;25:634–642. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.634.14572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Krueger KR, Hoganson G, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Early and late life cognitive activity and cognitive systems in old age. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. 2005;11:400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bach J, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yang J, James BD, Bennett DA. Early life instruction in foreign language and music and incidence of mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2015;29:292–302. doi: 10.1037/neu0000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Dong X, Leurgans SE, Evans DA. Cognitive decline after hospitalization in a community population of older persons. Neurology. 2012;78:950–956. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824d5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Loss of basic lexical knowledge in old age. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2011;82:369–372. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.212589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Cognitive decline in prodromal Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Archives of Neurology. 2010;68:351–356. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Participation in cognitively stimulating activities and risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287:742–748. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:1946–1952. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S, Hanoch Y, Barnes A, Liu PJ, Cummings J, Bhattacharya C, Rice T. Numeracy and Medicare part D: The importance of choice and literacy for numbers in optimizing decision making for Medicare’s prescription drug program. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26:295–307. doi: 10.1037/a0022028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]