Abstract

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) continue to be common and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. However, the underlying mechanisms in the combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) era are not fully understood. Interferon alpha (IFNα) is an antiviral cytokine found to be elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of individuals with advanced HIV-associated dementia in the pre-cART era. In this cross-sectional study, we investigated the association between IFNα and neurocognitive performance in ambulatory HIV-infected individuals with milder impairment. An eight test neuropsychological battery representing six cognitive domains was administered. Individual scores were adjusted for demographic characteristics and a composite neuropsychological score (NPT-8) was calculated. IFNα and CSF neurofilament light chain (NFL) levels were measured using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). There were 15 chronically infected participants with a history of significant immunocompromise (median nadir CD4+ of 49 cells/microliter). Most participants were neurocognitively impaired (mean Global Deficit Score of 0.86). CSF IFNα negatively correlated with three individual tests (Trailmaking A, Trailmaking B, and Stroop Color-word) as well as the composite NPT-8 score (r = −0.67, p = 0.006). These negative correlations persisted in multivariable analyses adjusting for chronic hepatitis B and C. Additionally, CSF IFNα correlated strongly with CSF NFL, a marker of neuronal damage (rho = 0.748, p= 0.0013). These results extend findings from individuals with severe HIV-associated dementia in the pre-cART era and suggest that IFNα may continue to play a role in HAND pathogenesis during the cART era. Further investigation into the role of IFNα is indicated.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, memory disorders, interferon alpha

Background

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) continue to be a major problem in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). Studies in mostly cART-treated populations have shown that HAND is present in 25–50% of HIV-infected individuals (Heaton et al, 2010; Robertson et al, 2007). In addition to being highly prevalent, HAND is associated with multiple adverse clinical outcomes, including decreased quality of life and increased mortality (Tozzi et al, 2003; Vivithanaporn et al, 2010). Yet, the pathogenesis of HAND, particularly in the setting of cART, has not been fully elucidated. A number of soluble biomarkers have been studied and are associated with the presence of HAND. Interestingly, many of these biomarkers appear to represent diverse pathological pathways (neopterin reflecting monocyte activation, neurofilament light chain reflecting neuronal degeneration, and others) (Hagberg et al, 2010; Marcotte et al, 2013; Peterson et al, 2014). Therefore, more research is needed to identify biomarkers that could contribute to a more comprehensive picture of HAND pathogenesis. Additionally, given that no treatments other than cART have been found to ameliorate HAND (Sacktor et al, 2011) (and even with cART the disorder is often not completely eradicated), new therapeutic targets are needed.

Interferon-alpha (IFNα) is an antiviral cytokine found to be the only type I interferon that is elevated in the plasma of HIV-infected individuals compared to uninfected controls (Hardy et al, 2013). IFNα has been shown to have a direct neurotoxic role in animal models as well as in humans. In a murine model of HIV encephalitis, mice develop altered behavior and express increased IFNα in the brain (Sas et al, 2009). Blockage of IFNα in the setting of this model has been shown to ameliorate encephalitis (Fritz-French et al, 2014). In humans, IFNα has been associated with significant neuropsychiatric toxicity when used for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection and other diseases (Fritz-French and Tyor, 2012). While found to be undetectable in >90% of normal individuals (Abbott et al, 1987), CSF IFNα levels were shown to be significantly elevated among individuals with HIV-associated dementia in the pre-cART era (Rho et al, 1995). However, given that HAND during the cART era is mostly comprised of milder impairment (Heaton et al, 2010), further research on the role of IFNα is indicated. Therefore, we sought to measure CSF IFNα in a cohort of predominantly cART experienced individuals to determine its relationship with neurocognitive performance.

Methods

Participants

HIV-infected adult outpatients who reported changes in memory were enrolled between March 2011 and November 2011 at the Emory University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) clinical core site in Atlanta, Georgia. In order to minimize confounding comorbidities, potential participants were excluded from the study for any of the following: 1) history of any neurologic disease known to effect memory (including stroke, malignancy involving the central nervous system, traumatic brain injury, and AIDS-related opportunistic infection of the central nervous system); 2) ongoing substance use (marijuana use in the last 7 days OR cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, or other non-marijuana illicit drug use in the last 30 days); 3) Heavy alcohol consumption in the last 30 days (defined as >7 drinks per week for women and >14 drinks per week for men); or 4) serious mental illness including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (depression was not excluded if participants were well controlled on treatment). Participants were also screened for hypothyroidism (with serum TSH level), vitamin B12 deficiency (with serum B12 level), and cryptococcal disease if CD4+ T-cell count was <100 cells/μl (with serum cryptococcal antigen) and excluded if any were found to be abnormal. Participants with a history of treated syphilis and a persistently positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer of 1:4 or less were eligible for the study if there was a decrease in RPR of at least fourfold at six months after treatment and there were no neurological symptoms at initial syphilis presentation. Lastly, participants were excluded in the event that severe cognitive symptoms had occurred precipitously in the last 30 days in order for further medical workup to be undertaken.

Neuropsychological Testing

The neuropsychological (NP) battery included the HIV dementia scale as well as the following eight tests that are used commonly in studies of cognition during HIV infection (Robertson and Yosief, 2014): 1) Trailmaking Part A; 2) Trailmaking Part B; 3) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test total recall; 4) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test delayed recall; 5) Grooved Pegboard (dominant hand); 6) Stroop Color/Word; 7) Letter Fluency (Controlled Oral Word Association Test) and 8) Animal Fluency. These tests were selected in order to examine at least five domains as recommended in the most recent nosology of HAND criteria (Antinori et al, 2007). The tests were administered by study staff after intensive training and supervision by an experienced, board certified neuropsychologist (DL). Test scores were adjusted for demographic characteristics using published norms (Heaton et al) that account for age, sex, and race (with the exception of HVLT and Stroop tests, for which adjusted values were not available) to arrive at individual T scores. A composite neuropsychological test score (NPT-8) was then calculated by averaging the eight individual T scores, as performed in other studies of neurocognition in HIV. Global Deficit Score (GDS), a validated measure of neurocognitive impairment in HIV based on demographically corrected T scores, was also calculated and as per published literature a score of ≥ 0.5 was indicative of neurocognitive impairment (Carey et al, 2004). The study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and written consent was obtained from all subjects.

Blood and Cerebrospinal Fluid Evaluations

On the same day of NP testing, paired blood and CSF samples were obtained, processed and stored at −80 degrees centigrade. Plasma and CSF HIV RNA levels were quantified with the Abbott laboratories Real Time HIV-1 assay (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction) using the Abbott m2000 system. Lowest limit of HIV detection was 40 copies/ml. IFNα levels were measured using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (PBL Assay Science, Piscataway NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and technicians were blinded to clinical data. All samples and standards were measured in triplicates as picograms/ milliter (pg/ml). CSF neurofilament light chain (NFL), an established marker of neuronal injury (Peterson et al, 2014), was also measured by ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Umea, Sweden). The NFL assay is most specific for myelinated axons and has intra-assay coefficients of variation below 10%. All NFL samples were analyzed as single samples in one round of experiments using one batch of reagents by board-certified laboratory technicians who were blinded to clinical data. Other studies including CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts were performed by the hospital clinical laboratories. In addition to the HIV-infected participant samples, the cerebrospinal fluid samples from four HIV-seronegative individuals were included for IFNα testing.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.4, SAS institute, Cary, NC) as well as SAS JMP (version 12.0, SAS institute, Cary, NC). Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences between non-normal groups were calculated with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. For correlations, non-normal variables were log10 transformed for the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient (r). If log10 transformation did not yield values that met criteria for normality, the Spearman correlation test (rho) was used. Alpha levels were two-tailed and a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses with multiple p values of < 0.05 were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure. For correlations between IFNα and NP measures that remained statistically significant after FDR, linear regression analysis (Analysis of covariance, ANCOVA) was then used to generate adjusted Pearson correlation coefficients accounting for the presence of chronic hepatitis B or C.

Results

A total of 15 HIV-infected participants were enrolled. Median age (table 1) was 49 years, 80% were men, and 73.3% were African-American. Most subjects had a long history (median 8 years) of HIV and a history of significant immunocompromise (median CD4+ nadir of 49 cells/μl and median current CD4+ of 62 cells/μl). The majority of subjects (60%) were cART experienced and 20% were currently on cART with undetectable plasma and CSF HIV RNA < 40 copies/ml. Mean NPT-8 score was 43.7 (standard deviation 9.34) and mean GDS of 0.86 (standard deviation 0.995). 9 of 15 subjects (60%) met criteria for neurocognitive impairment by GDS ≥ 0.5 while 4 of 15 (26.7%) had more severe impairment with GDS ≥1.5. Median CSF IFNα result was 7.86 pg/ml (range 2.62–45.95) and median CSF NFL result was 563 pg/ml (range 293–12233). CSF IFNα correlated significantly with CSF NFL (rho = 0.748, p= 0.0013).

Table 1.

Participant demographic and disease characteristics (see box for abbreviations)

| Variable | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| N = 15 unless otherwise stated | or median (IQR; range) |

| or mean [Standard deviation] | |

| Age in years | 49 (43–52; 35–59) |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male | 12 (80%) |

| Female | 3 (20%) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| African-American | 11 (73.3%) |

| Caucasian | 4 (26.7%) |

|

| |

| Years of HIV diagnosis | 8 (2–14; <1–25) |

| Co-morbidities | |

| Current cigarette smoker | 9 (60%) |

| Hepatitis C positive | 3 (20%) |

| Hypertension | 2 (13.3%) |

| Depression | 2 (13.3%) |

| Hepatitis B positive | 1 (6.7%) |

|

| |

| cART naïve | 6 (40%) |

| cART experienced but off treatment | 6 (40%) |

| Currently on cART | 3 (20%) |

|

| |

| Laboratory results | |

| CD4 count (cells/μl) | 62 (29–201; 10–922) |

| CD4% | 10 (4–21; 1–39) |

| CD4 nadir (n=13) | 49 (20–102.5; 10–153) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.8 (12–14.2; 9.4–15.7) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4; 0.7–1.6) |

| Plasma IFN-α (pg/ml, n=14) | 26.5 (2.82–103.02; 0–209.73) |

| Log Plasma HIV (detectable n=12) | 4.76 (3.92–5.34; 3.6–5.82) |

| CSF WBC | 0 (0–4; 0–12) |

| CSF RBC | 0 (0–1; 0–58) |

| CSF Protein | 38.5 (33.25–52.75; 15–95) |

| Log CSF HIV (detectable n= 12) | 3.09 (2.70–4.16; 1.61–5.25) |

| CSF IFN-α (pg/ml) | 7.86 (6.43–12.62; 2.62–45.95) |

| CSF NFL (pg/ml) | 563 (487–826; 293–12233) |

|

| |

| Neuropsychological testing | |

| HIV dementia scale score | 11.47 [3.91] |

| NPT-8 | 43.7 [9.34] |

| GDS | 0.86 [0.995] |

IQR = interquartile range; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy; CD = cluster of differentiation; μl= microliters; g = grams; dl = deciliter; mg = milligrams; pg= picograms; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; WBC = white blood cell count; RBC = red blood cell count; IFNα = interferon alpha; NFL= Neurofilament light chain; NPT = composite neuropsychological test score; GDS = global deficit score

There were two healthy HIV-seronegative controls (one 57 year old female with CSF IFNα level of 2.14 pg/ml and one 52 year old female with CSF IFNα 1.19 pg/ml) as well as two HIV-seronegative individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (one 64 year old male with CSF IFNα 5.95 pg/ml and one 73 year old female with CSF IFNα 3.1 pg/ml). CSF IFNα level was significantly higher (p=0.012) in the participants with HIV (median 7.86 pg/ml, overall range 2.62–45.95) compared to the participants without HIV. When limiting the comparison to the two Alzheimer’s disease participants, HIV-infected participants tended to have higher CSF IFNα but this difference was not statistically significant (p= 0.13).

In the HIV-infected participants, there was no significant difference (p=0.94) in plasma IFNα levels between participants on cART with undetectable plasma/CSF HIV RNA (median 34.1 pg/ml, interquartile range [IQR] 3.07 – 98.73) and participants off cART (median 18.9 pg/ml, IQR 2.07–115.9). Similarly, CSF IFNα levels did not significantly differ (p=0.31) between participants on cART with undetectable plasma/CSF HIV RNA (median 7.38 pg/ml, IQR 4.52 – 7.86) and participants off cART (median 8.34 pg/ml, IQR 6.67 – 16.55). There was no statistical difference (p=0.28) in plasma IFNα among participants with either active hepatitis B or C (median 39.9 pg/ml, IQR 18.9 – 209.73) versus participants without (15.9 pg/ml, IQR 2.07 – 98.73). Similarly, there was no statistical difference (p=0.69) in CSF IFNα levels among participants with either active hepatitis B or C (median 9.5 pg/ml, IQR 6.67 – 37.38) versus participants without (median 7.86 pg/ml, IQR 4.52 – 12.62).

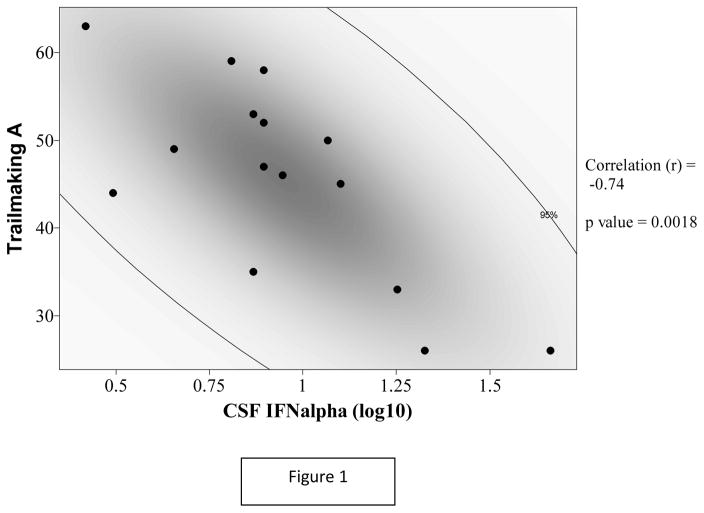

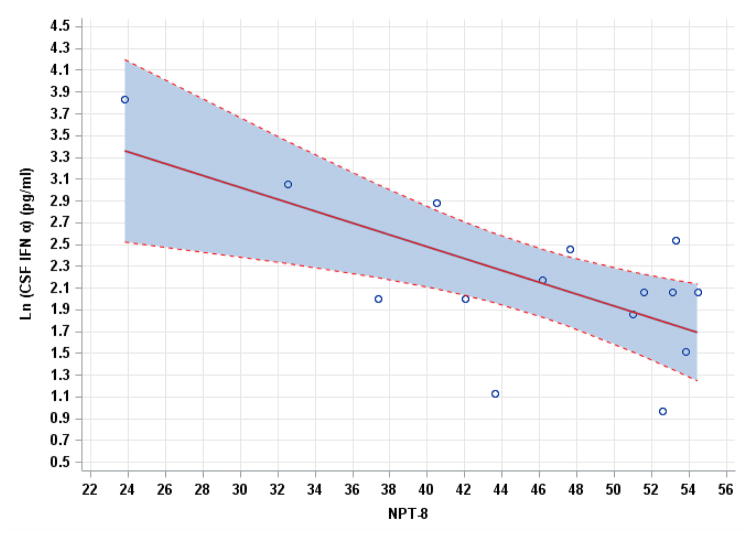

There were multiple negative correlations between CSF IFNα levels and neurocognitive performance that were statistically significant (table 2). CSF IFNα correlated negatively with composite NPT-8 score (r = −0.67, p = 0.006). In terms of individual NP tests, CSF IFNα correlated negatively with Trailmaking test A (r = −0.735, p = 0.0018, see figure 1 with 95% density ellipse), Trailmaking test B (r = −0.677, p = 0.006), and Stroop color-word test (r = −0.67, p = 0.009). These three correlations remained statistically significant after false discovery rate correction (p values= 0.014, 0.022, and 0.025 respectively). There was only one significant correlation with plasma IFNα (Trailmaking test A, r = −0.561, p = 0.037), but this correlation became non-significant (p = 0.28) after false discovery rate correction. Pearson correlation coefficients between CSF IFNα and the identified NP performance measures remained similarly significant in the multivariable analyses adjusting for the presence of chronic hepatitis B or C (see table 2). Figure two shows the linear regression analysis between CSF IFNα and NPT-8 (Y = 4.6564 – 0.05452X; standard deviation = 0.5581).

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between IFNα (Log10 transformation) and Neurocognitive Performance

| NC performance measure | CSF IFNα (p value) | Plasma IFNα (p value) | * CSF IFNα adjusted r (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPT-8 | −0.67 (0.006) | NS | −0.68 (0.02) |

| Trailmaking A | −0.735 (0.002) | −0.561 (0.037) | −0.76 (0.003) |

| Trailmaking B | −0.677 (0.006) | NS | −0.69 (0.01) |

| HVLT total | NS | NS | |

| HVLT delay | NS | NS | |

| Pegboard dominant | NS | NS | |

| Stroop Color word | −0.67 (0.009) | NS | −0.69 (0.02) |

| Letter Fluency | NS | NS | |

| Animal Fluency | NS | NS |

Abbreviations: CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; IFNα = interferon alpha; NPT = composite neuropsychological test score; NS = not significant; GDS = global deficit score; HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test

Adjusted for the presence of chronic hepatitis B or C

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Linear regression relationship between CSF IFNα and NPT-8 with 95% confidence interval in shaded blue

When comparing participants with GDS ≥0.5 versus < 0.5, there was no significant difference in CSF IFNα levels (median 8.81 pg/ml [IQR 5.24–19.5] versus median 7.86 [IQR 5.95–9.05], p=0.59) or in plasma IFNα levels (median 37 pg/ml [IQR 5.53–175.4] versus median 11.65 pg/ml [IQR 2.3–103.02], p=0.61). However, when grouped by severe impairment (GDS ≥1.5 versus < 1.5), participants with severe impairment had significantly higher CSF IFNα levels (median 19.53 pg/ml [IQR 10.0–39.76] versus median 7.86 pg/ml [IQR 4.52–8.81], p=0.049). Participants with GDS ≥1.5 versus < 1.5 tended to have higher plasma IFNα levels (median 94.4 pg/ml [IQR 39.9–202.4] versus median 15.9 pg/ml [IQR 2.07–98.73]) but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.16).

Discussion

Given the high prevalence of HANDs in the cART era, there is an ongoing need to better understand the mechanisms behind these disorders. CSF levels of IFNα, an antiviral cytokine with neurotoxic properties, were found in the pre-cART era by members of our group to be significantly elevated among individuals with HIV-associated dementia (Rho et al, 1995). However, it is unclear if this cytokine remains associated with HAND in the modern HIV treatment era, in which most affected individuals have milder forms of neurocognitive impairment. While the present study represents a small sample size, the study population was comprised of ambulatory outpatients who did not have advanced dementia. Our results show that CSF IFNα levels negatively correlate with multiple measures of neurocognitive function, including a composite score that reflects global performance. These correlations may have been driven by participants with more significant impairment (a GDS of ≥1.5 as suggested by other studies) (Cysique et al, 2015). Participants with GDS ≥1.5 had significantly higher CSF IFNα levels.

Of note, the individual tests (Trailmaking and Stroop) that were negatively associated with CSF IFNα and appeared to underpin the overall negative association with composite performance are generally regarded as tests of executive function and processing speed. These contrast with the other individual tests in our battery (which evaluated memory, fluency, and motor skill) that were not associated with CSF IFNα. Our findings suggest that the detrimental effects of IFNα may be most specific to brain regions that are linked to executive function (such as the frontal lobes and associated subcortical tracts) and processing speed (such as white matter). This is supported by the strong correlation between CSF IFNα and CSF NFL, an established marker of injury to large caliber myelinated axons in HIV and other CNS diseases (Peterson et al, 2014; Skillback et al, 2014; Zetterberg et al, 2016).

However, we acknowledge that the mechanism of IFNα-induced neurotoxicity is not fully understood at this time (Fritz-French and Tyor, 2012; Kessing and Tyor, 2015). IFNα initiates an antiviral response by binding to the type I IFN receptor (IFNAR) with subsequent activation of the JAK/STAT pathway. However, blocking the IFNAR only partially prevents neurotoxicity caused by IFNα, suggesting that the cellular signaling involved in IFNα neurotoxicity is more complex than binding to its own receptor. The NMDA receptor (NMDAR) has also been linked to IFNα toxicity in clinical and in vitro studies (Quarantini et al, 2006). Interestingly, other neurotoxins that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of HAND also appear to act through the NMDAR (Potter et al, 2013). Targeting NMDAR mediated excitotoxicity may be a common pathway and further research is needed to identify HAND therapeutic candidates that would complement cART.

We acknowledge the limitations of the study, including the small sample size. We had very few HIV-seronegative controls, though previous research has shown that CSF IFNα is undetectable or near undetectable in the vast majority of healthy individuals (Abbott et al, 1987). Two of these HIV seronegative subjects had Alzheimer’s disease, and while these individuals appeared to have lower CSF IFNα levels than the HIV-infected individuals, we were not able to reject the null hypothesis that there was no statistical difference between Alzheimer’s and HIV groups. It is very likely that our study was under-powered to effectively address this question. Larger studies that include more healthy HIV-seronegative individuals, more individuals with Alzeimer’s disease, and more HIV-infected individuals with long term virologic suppression on cART will be needed to determine if CSF IFNα levels are different between these groups.

We also acknowledge that one third of study subjects had either chronic hepatitis B or C. Since the presence of chronic hepatitis has been shown to effect systemic interferon alpha levels (Kakumu et al, 1989), the inclusion of these individuals may have influenced our results. However, the multivariable analysis adjusting for the presence of chronic hepatitis revealed similar negative correlations between CSF IFNα and NP performance. A larger study that excludes individuals with chronic hepatitis B/C would be needed to completely rule out the influence of hepatitis on IFNα.

While the majority of subjects in the study were cART experienced, a minority were on cART at the time of the study with suppressed plasma and CSF HIV RNA levels. While we did not find that plasma or CSF IFNα levels were lower in the individuals on cART, the sample size of subjects on cART was too small to perform a separate analysis limited to this group. Therefore our results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to HIV-infected individuals who have achieved virologic suppression on cART. Ideally a larger study would be performed focusing on patients with neurocognitive impairment despite virologic suppression on cART. Given the persistence of HAND in the cART era, more research is needed to better understand the relationship between IFNα and neurocognition in HIV-infected individuals.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Emory Medical Care Foundation

NIH K23MH095679

NIH P30 AI050409 (Emory Center for AIDS Research)

The Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation

The Torsten Söderberg Foundation

The Swedish Research Council

The European Research Council

Footnotes

Disclaimer:

No financial disclosures to report

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

This work was presented in part as: CSF Interferon Alpha Levels Inversely Correlate with Processing in HIV-infected Subjects with Cognitive Complaints. Poster Abstract 437, 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), Atlanta, Georgia, 2013.

References

- Abbott RJ, Bolderson I, Gruer PJ. Assessment of an immunoassay for interferon-alpha in cerebrospinal fluid as a diagnostic aid in infections of the central nervous system. J Infect. 1987;15:153–60. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(87)93147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–99. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, Conover E, Marcotte TD, Grant I, Heaton RK, Group H. Predictive validity of global deficit scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:307–19. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cysique LA, Hewitt T, Croitoru-Lamoury J, Taddei K, Martins RN, Chew CS, Davies NN, Price P, Brew BJ. APOE epsilon4 moderates abnormal CSF-abeta-42 levels, while neurocognitive impairment is associated with abnormal CSF tau levels in HIV+ individuals - a cross-sectional observational study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:51. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0298-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz-French C, Shawahna R, Ward JE, Maroun LE, Tyor WR. The recombinant vaccinia virus gene product, B18R, neutralizes interferon alpha and alleviates histopathological complications in an HIV encephalitis mouse model. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014;34:510–7. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz-French C, Tyor W. Interferon-alpha (IFNalpha) neurotoxicity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2012;23:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg L, Cinque P, Gisslen M, Brew BJ, Spudich S, Bestetti A, Price RW, Fuchs D. Cerebrospinal fluid neopterin: an informative biomarker of central nervous system immune activation in HIV-1 infection. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy GA, Sieg S, Rodriguez B, Anthony D, Asaad R, Jiang W, Mudd J, Schacker T, Funderburg NT, Pilch-Cooper HA, Debernardo R, Rabin RL, Lederman MM, Harding CV. Interferon-alpha is the primary plasma type-I IFN in HIV-1 infection and correlates with immune activation and disease markers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I, Group C. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–96. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised Comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead- Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults scoring program. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Kakumu S, Fuji A, Yoshioka K, Tahara H. Serum levels of alpha-interferon and gamma-interferon in patients with acute and chronic viral hepatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1989;36:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing CF, Tyor WR. Interferon-alpha induces neurotoxicity through activation of the type I receptor and the GluN2A subunit of the NMDA receptor. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2015;35:317–24. doi: 10.1089/jir.2014.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte TD, Deutsch R, Michael BD, Franklin D, Cookson DR, Bharti AR, Grant I, Letendre SL for the CG. A Concise Panel of Biomarkers Identifies Neurocognitive Functioning Changes in HIV-Infected Individuals. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9504-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J, Gisslen M, Zetterberg H, Fuchs D, Shacklett BL, Hagberg L, Yiannoutsos CT, Spudich SS, Price RW. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) neuronal biomarkers across the spectrum of HIV infection: hierarchy of injury and detection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e116081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter MC, Figuera-Losada M, Rojas C, Slusher BS. Targeting the glutamatergic system for the treatment of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:594–607. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9442-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarantini LC, Miranda-Scippa A, Schinoni MI, Sampaio AS, Santos-Jesus R, Bressan RA, Tatsch F, de Oliveira I, Parana R. Effect of amantadine on depressive symptoms in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with pegylated interferon: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2006;29:138–43. doi: 10.1097/01.WNF.0000220824.57769.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho MB, Wesselingh S, Glass JD, McArthur JC, Choi S, Griffin J, Tyor WR. A potential role for interferon-alpha in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated dementia. Brain Behav Immun. 1995;9:366–77. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1995.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K, Yosief S. Neurocognitive assessment in the diagnosis of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Semin Neurol. 2014;34:21–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KR, Smurzynski M, Parsons TD, Wu K, Bosch RJ, Wu J, McArthur JC, Collier AC, Evans SR, Ellis RJ. The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. AIDS. 2007;21:1915–21. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32828e4e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacktor N, Miyahara S, Deng L, Evans S, Schifitto G, Cohen BA, Paul R, Robertson K, Jarocki B, Scarsi K, Coombs RW, Zink MC, Nath A, Smith E, Ellis RJ, Singer E, Weihe J, McCarthy S, Hosey L, Clifford DB team AA. Minocycline treatment for HIV-associated cognitive impairment: results from a randomized trial. Neurology. 2011;77:1135–42. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822f0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sas AR, Bimonte-Nelson H, Smothers CT, Woodward J, Tyor WR. Interferon-alpha causes neuronal dysfunction in encephalitis. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3948–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5595-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skillback T, Farahmand B, Bartlett JW, Rosen C, Mattsson N, Nagga K, Kilander L, Religa D, Wimo A, Winblad B, Rosengren L, Schott JM, Blennow K, Eriksdotter M, Zetterberg H. CSF neurofilament light differs in neurodegenerative diseases and predicts severity and survival. Neurology. 2014;83:1945–53. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi V, Balestra P, Galgani S, Murri R, Bellagamba R, Narciso P, Antinori A, Giulianelli M, Tosi G, Costa M, Sampaolesi A, Fantoni M, Noto P, Ippolito G, Wu AW. Neurocognitive performance and quality of life in patients with HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:643–52. doi: 10.1089/088922203322280856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivithanaporn P, Heo G, Gamble J, Krentz HB, Hoke A, Gill MJ, Power C. Neurologic disease burden in treated HIV/AIDS predicts survival: a population-based study. Neurology. 2010;75:1150–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d5bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetterberg H, Skillback T, Mattsson N, Trojanowski JQ, Portelius E, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Blennow K Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Association of Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Concentration With Alzheimer Disease Progression. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:60–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]