Abstract

Introduction

We report our experience with extended right hemicolectomy (ERH) and left hemicolectomy (LH) for the treatment of cancers located between the distal transverse and the proximal descending colon, and compare postoperative morbidity, mortality, pathological results and survival for the two techniques.

Methods

A retrospective review was performed of a single institution series over ten years. Patients who underwent different operations, had benign disease or received palliative resections were excluded. Data collected were patient demographics, type and duration of surgery, tumour site, postoperative complications and histology results.

Results

Ninety-eight patients were analysed (64 ERHs, 34 LHs). ERH was conducted using an open approach in 93.8% of cases compared with 73.5% for LH. The anastomotic leak rate was similar for both groups (ERH: 6.3%, LH: 5.9%). This was also the case for other postoperative complications, mortality (ERH: 1.6%, LH: 2.9%) and overall survival (ERH: 50.4 months, LH: 51.8 months). All but one patient in the ERH cohort had clear surgical margins. Nodal evaluation for staging was adequate in 78.1% of ERH cases and 58.8% of LH cases.

Conclusions

In our experience, both ERH and LH are adequate for tumours located between the distal transverse and the proximal descending colon.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Surgery, Hemicolectomy, Outcomes

Tumours located between the distal transverse and proximal descending colon can be approached with different surgical techniques. Historically, transverse segmental resections or extended left hemicolectomies (LHs) were used for transverse colon cancers while classic LH was the most used operation for descending colon cancers. Transverse segmental resections or extended LHs leave short transverse stumps that necessitate complex technical reconstructions (ie right colonic transpositions or complete intestinal derotations)1 and have a high risk of leaks.2 Furthermore, it is generally believed that the colocolic anastomosis carries a higher risk of leakage than right-sided resections2,3 owing to the differences in vascularity between the large and small bowel although not all authors agree on this point.

The first descriptions of extended right hemicolectomy (ERH) involved the treatment of right-sided colonic tumours.4–6 Subsequently, it became evident that this was also a valuable alternative to LH for tumours located between the distal transverse colon and proximal descending colon.7 ERH for the treatment of left-sided colonic tumours was first reported in 1985 and showed significant technical advantages over left colectomies or transverse segmental resections at the expense of longer segments of bowel resected.8 Technically, it utilises a highly mobile segment of the bowel, the ileum, to transpose it towards the left colon and perform the ileocolonic anastomosis without tension.8,9

ERH has also been conducted laparoscopically,7,10 and in both elective and emergency settings.11,12 In cases of obstructing tumours of the left colon, it simultaneously removes the caecum, which is the segment at highest risk of perforation (Laplace law).11 It is therefore generally felt that ERH achieves in one single operation the relief of intestinal obstruction, tumour resection and the restoration of the gut’s continuity with a tension free anastomosis.8

Given the difference in the amount of bowel resected with the eventual physiological consequences for the patient, a comparison is necessary between ERH and LH, especially with regard to improving quality of life and increased focus on enhanced recovery protocols. However, a functional study can be conducted only after postoperative outcomes, oncological results and survival have been demonstrated to be similar for the two techniques.13,14 Although ERH is a longstanding, time honoured procedure for the treatment of left-sided colonic tumours, not many ERH studies are present in the literature, and none of them report ERH and LH results in the same series. The aim of this study was to review our series with ERH and LH over ten years of activity, outlining differences for postoperative morbidity, mortality, pathological analysis and survival.

Methods

A retrospective study was performed on patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery at Kettering General Hospital between 2003 and 2012. Patients were included for analysis if they underwent ERH or LH for resections of colorectal tumours located between the distal transverse and proximal descending colon. Those who underwent surgery for benign disease (ulcerative colitis, villous adenoma) were excluded.

The colorectal unit at our hospital has a prospectively maintained database that includes basic demographics and clinical data such as age, sex, year of surgery, location of the tumour and type of operation performed. For patients included in the study, the hospital electronic databases and medical notes were searched for different groups of data: preoperative (ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] grade, modality of presentation [elective vs emergency]), intraoperative (laparoscopic vs open, covering stoma, operative time), early postoperative (30-day morbidity and mortality), pathological (TNM [tumour, lymph nodes, metastasis] and Dukes’ staging, tumour grading, length of resected bowel, length of cancer according to the maximum diameter, resection margin length and involvement [R1/R2], number of lymph nodes evaluated) and overall survival (OS).

For ERH, the ileocolic, right colic, middle colic and ascending branch of the left colic vessels were ligated. For LH, the left colic and left branch of the middle colic vessels were ligated. The minimum number of lymph nodes to be evaluated for correct staging has been defined as 12.15–17

The primary outcome was early postoperative morbidity. Secondary outcomes included postoperative mortality and pathological results in terms of radicality of resection (surgical margins) and number of lymph nodes evaluated.

Statistical analysis

All data were inserted into Excel® (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, US) and analysed with SPSS® version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, US). Normality assumptions were demonstrated with histograms and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Differences between the groups were compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous parametric variables, the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous non-parametric variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables (or Fisher’s exact test if the counts in cells were <5). Factors influencing the duration of surgery were examined using univariate ANOVA. Analysis for OS was performed with Kaplan–Meier curves and the logrank test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

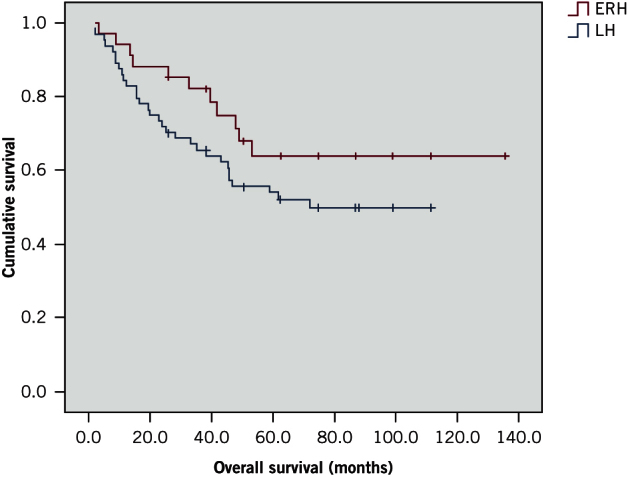

Between 2003 and 2012, 98 patients (64 ERHs, 34 LHs) matched the inclusion criteria. Results concerning clinical characteristics, postoperative complications, histopathological analysis and OS are presented in Tables 1–3 and Figure 1. Two patients died, one in each cohort. The ERH patient (1.6%) suffered a postoperative chest infection complicated by atrial fibrillation and the LH patient (2.9%) had a myocardial infarction following atrial fibrillation.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| ERH (n=64) | LH (n=34) | p-value | |

| Male sex | 37 (57.8%) | 19 (55.9%) | 1.000 |

| Mean age in years | 70.3 (SD: 10.7) |

70.0 (SD: 10.1) |

0.528 |

| Emergency | 27 (42.2%) | 9 (26.5%) | 0.115 |

|

Approach Open Laparoscopic Laparoscopic converted to open |

60 (93.8%) 4 (6.3%) 0 (0%) |

25 (73.5%) 7 (20.6%) 2 (5.9%) |

0.002 |

|

ASA grade 1 2 3 4 |

5 (7.8%) 42 (65.6%) 16 (25.0%) 1 (1.6%) |

6 (17.6%) 18 (52.9%) 9 (26.5%) 1 (2.9%) |

0.563 |

| Mean operative time in minutes | 133 (SD: 50) | 158 (SD: 41) | 0.039 |

| Protective stoma | 0 | 0 | – |

| Perioperative morbidity | 14 (21.9%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0.784 |

| Perioperative mortality | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.206 |

| Mean overall survival (range) in months | 50.4 (2.0–111.2) | 51.8 (3.1–135.6) | 0.156 |

ERH = extended right hemicolectomy; LH = left hemicolectomy; SD = standard deviation; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists

Table 3.

Histopathological analysis

| ERH (n=64) | LH (n=34) | p-value | |

| T stage pT1 pT2 pT3 pT4 |

1 (1.6%) 6 (9.4%) 34 (53.1%) 23 (35.9%) |

4 (11.8%) 2 (5.9%) 21 (61.8%) 7 (20.6%) |

0.076 |

| N stage pN0 pN1 pN2 |

37 (57.8%) 19 (29.7%) 8 (12.5%) |

19 (55.9%) 13 (38.2%) 2 (5.9%) |

0.481 |

| M stage pMx pM1 |

62 (96.9%) 2 (3.1%) |

32 (94.1%) 2 (5.9%) |

0.608 |

| Differentiation Poorly differentiated Moderately differentiated Well differentiated |

13 (20.3%) 51 (79.7%) 0 (0%) |

6 (17.6%) 28 (82.4%) 0 (0%) |

1.000 |

| Dukes classification A B C D |

7 (10.9%) 30 (46.9%) 27 (42.2%) 0 (0%) |

6 (17.6%) 13 (38.2%) 15 (44.1%) 0 (0%) |

0.563 |

| Mean length of bowel resected in cm | 47 (SD: 17) | 28 (SD: 15) | <0.001 |

| Mean length of tumour in mm | 49 (SD: 22) | 41 (SD: 17) | 0.061 |

| Median length for clear margins (range) in cm | 6.5 (1.5–25.0)* | 6.0 (1.1–30.0) | 0.249 |

| Margins classified as R1/R2 | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Median number of lymph nodes analysed (range) | 16 (5–39) | 13 (4–23) | 0.051 |

| Lymph node analysis Patients with ≥12 nodes evaluated Patients with <12 nodes evaluated |

50 (78.1%) 14 (21.9%) |

20 (58.8%) 14 (41.2%) |

0.044 |

ERH = extended right hemicolectomy; LH = left hemicolectomy; SD = standard deviation

*n=63 (The margin was involved for one patient so no length was reported for this case.)

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing survival for extended right hemicolectomy (ERH) and left hemicolectomy (LH) patients

The laparoscopic approach was more frequent and the mean duration of surgery was longer for LH patients than in the ERH group (Table 1). A higher proportion of cases were operated on as an emergency in the ERH group than in the LH group although the difference was not significant (Table 1). The occurrence of overall postoperative morbidity, anastomotic leakage and other complications was similar for the two cohorts (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Postoperative complications

| 30-day morbidity | ERH (n=64) | LH (n=34) | p-value |

| Anastomotic leak | 4 (6.3%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1.000 |

| Chest infection | 4 (6.3%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1.000 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (4.7%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0.653 |

| Postoperative ileus | 3 (4.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.549 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.539 |

| Heart failure | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.319 |

| Acute renal failure | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Clostridium difficile colitis | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.539 |

| Wound infection | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

ERH = extended right hemicolectomy; LH = left hemicolectomy

The mean length of specimen resected was longer for ERH than for LH (Table 3). The median number of lymph nodes examined was similar for the two groups although there was a trend suggesting that ERH patients were more likely to have more nodes analysed than those undergoing LH (Table 3). A higher proportion of patients had ≥12 lymph nodes evaluated in the ERH cohort (Table 3). No significant differences were found for the other parameters analysed. Both the approach used (laparoscopic vs open) and the length of specimen resected influenced the duration of surgery (univariate ANOVA, p=0.009 and p=0.002 respectively).

Discussion

To our knowledge, there is little guidance in the literature on how to handle colorectal cancers located between the distal transverse and the proximal descending colon. Two procedures are used most frequently (ERH and LH) but studies presenting comparative results are still lacking. In our study, both ERH and LH had a higher percentage of patients presenting as an emergency than in the UK’s national bowel cancer audit and large series (17–22%).18–20 While LH had figures that were still comparable (26.5%), emergency presentations in the ERH group (42.2%) were double the national average.

Emergency vs elective procedure

The high prevalence of emergency patients treated with ERH can be attributed to the fact that emergency cases are more likely to be performed by non-‘colorectal’ surgeons and most would perform an ERH in the emergency setting. In our institution, ERH is conducted mainly to remove both the primary cancer and the diseased caecum in a single operation when the latter is perforated or damaged from the pneumatic distension caused by an obstructing left-sided tumour located downstream (Laplace law). The incidence of emergency presentations was consequently higher in the ERH group than in the LH group and the national average18 because this procedure was selected more frequently in cases of obstruction or caecal perforation. However, the difference between the two operations did not reach statistical significance (p=0.115). As a result, the two patient cohorts can still be considered homogeneous and comparable.

Operative time

LH generally lasted longer than ERH in our series. This could prolong surgical stress and increase risk, particularly in frail and unstable patients. The approach used (laparoscopic vs open) and the length of bowel resected influenced the duration of surgery. Laparoscopic surgery usually results in longer operations than open surgery. In our series, the laparoscopic approach was more frequent for LH than for ERH owing to the increased technical difficulty in transecting the middle colic vessels laparoscopically during ERH.7 The length of bowel resected is longer for ERH than for LH because of the additional resection of the right colon, which requires extra operative time. Accordingly, the operative time for LH is influenced positively by the shorter bowel resection but negatively by the laparoscopic approach. Both factors therefore have to be considered, especially for patients who require a quick operation.

Morbidity

Conventional wisdom would suggest that colocolic anastomosis (such as performed in LH) carries an increased risk of failure over ileocolic anastomosis (such as performed in ERH) because of the difference in the local vascularity of the stumps. As a result, one could expect a difference in anastomotic leak rate between the two techniques. However, not every study has demonstrated conclusively that colocolic anastomoses are more prone to leaking than ileocolic anastomoses. In our study, there were no significant differences between ERH and LH in leak rate or any other factors associated with the occurrence of leaks (ASA grade, consultant performing the operation, emergency modality or laparoscopic approach).

ERH interrupts more major vessels of the colon than LH and one could therefore postulate that postoperative bleeding is more likely. Furthermore, the surface area where ooze is possible is greater with ERH because of the greater amount of dissection compared with LH. Despite this, in our study, no patients in either group experienced a postoperative haemorrhage that required reoperation.

Surgical margins and lymph node evaluation

Both cohorts were similar in terms of preoperative cancer staging and grading, and no significant difference was observed for OS. There was also no difference between the groups for margin involvement (R1 and R2) because a radical oncological resection (R0) was achieved in all but one patient.

The adequacy of lymph node examination for accurate cancer staging has been a longstanding problem in colorectal surgery.14 Based on current guidelines, a minimum of 12 nodes should be evaluated for reliable staging.15–17 This threshold provides a recognised standard to avoid inadequate sampling and understaging, which is still present in large series.21 In our series, the median number of lymph nodes analysed per patient was ≥12 in both groups. The ERH group had a higher proportion of patients with adequate node analysis than the LH cohort.

Numerous risk factors for inadequate lymph node retrieval have been presented but those related to surgical technique mostly involve the length of bowel resected, proportional to the amount of mesentery provided for analysis. Moreover, a study by Bilchik and Trocha showed that 29% of colorectal cancer patients undergoing lymphatic mapping at the time of resection had aberrant drainage,22 and skip metastasis is being observed more frequently as technologies more sensitive in detection of micrometastasis are being used.23

ERH also removes the entire lymphatic basin of the transverse colon, thereby avoiding the risk of missing skip metastasis, especially for tumours of the distal transverse that can still metastasise to portions of the mesentery not normally resected during a standard LH lymphadenectomy. However, the two operations generally capture very different drainage patterns and the extra lymph nodes available for analysis in ERH may not be relevant to cancer staging for most patients: the additional nodes provided by the right bowel are often far away from the primary cancer and are therefore unlikely to be involved. Until the contribution of the extra lymph nodes provided with ERH is clarified, it is important to consider that ERH increases the number of nodes retrieved compared with LH but at the expense of additional length of bowel being resected.

Study limitations

Two main limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective nature of the design means that there may have been selection bias. Groups were already homogeneous for relevant parameters including age, sex, tumour size, location, surgeon performing the operation, and the surgeon’s experience with ERH and LH. Unfortunately, it is difficult to investigate retrospectively why some patients underwent ERH or LH. An exception was made for patients who presented as an emergency with intraoperative findings of a damaged caecum, where ERH was the operation of choice. Other factors may have influenced the decision making process that were not recorded in the notes.

Second, one of the reasons not to perform an ERC would be the eventual effects on bowel function due to the longer resection. In times of enhanced recovery programmes, particular attention has to be given to the functional outcomes and the patient’s quality of life instead of just the classic immediate postoperative and long-term oncological outcomes. The additional removal of the colon and ileocaecal valve with ERC may impact on the number of bowel motions per day and produce diarrhoea. It can also affect nutrient absorption, faecal continence and the sensation of urgency. Unfortunately, these parameters could not be addressed in a retrospective study as most of them were not recorded in the notes, especially for earlier operations. In fact, analysis in terms of patients’ enhanced recovery outcomes was not possible because specific protocols were introduced relatively late compared with our recruitment period.24

The definitive message of our study is that no significant differences were present in our series regarding the immediate postoperative outcomes for the two operations. This similarity forms the basis for a future prospective study aiming at further investigating eventual differences in functional outcomes.

Conclusions

ERH is an established procedure for tumours located between the distal transverse and proximal descending colon, both for emergency and elective colorectal cancer resections. In our series, ERH and LH produced similar results with regard to early postoperative outcomes and late cancer specific outcomes, and either could be used for such tumours.

References

- 1.Dumont F, Da Re C, Goéré D et al. Options and outcome for reconstruction after extended left hemicolectomy. Colorectal Dis 2013; : 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakker IS, Grossmann I, Henneman D et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage and leak-related mortality after colonic cancer surgery in a nationwide audit. Br J Surg 2014; : 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krarup PM, Jorgensen LN, Andreasen AH, Harling H. A nationwide study on anastomotic leakage after colonic cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis 2012; : e661–e667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delannoy E, Gautier P, Devambez J, Toison G. Extended right hemicolectomy for cancer of the right colon. Lille Chir 1954; : 243–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher HW. Extended right hemicolectomy; the treatment of advanced carcinoma of the hepatic flexure and malignant duodenocolic fistula. Br J Surg 1960; : 616–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouasakao N, Druart R, Dupres M et al. Colo-duodenal fistula caused by cancer of the right colonic flexure treated by right extended hemicolectomy associated with a mucosal patch using a terminal ileal pedicled graft. Apropos of a case. J Chir 1984; : 757–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chew SS, Adams WJ. Laparoscopic hand-assisted extended right hemicolectomy for cancer management. Surg Endosc 2007; : 1,654–1,656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan WP, Jenkins N, Lewis P, Aubrey DA. Management of obstructing carcinoma of the left colon by extended right hemicolectomy. Am J Surg 1985; : 327–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farmer KC, Phillips RK. True and false large bowel obstruction. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol 1991; : 563–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlachta CM, Mamazza J, Poulin EC. Are transverse colon cancers suitable for laparoscopic resection? Surg Endosc 2007; : 396–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antal SC, Kovacs ZG, Feigenbaum V, Engelberg M. Obstructing carcinoma of the left colon: treatment by extended right hemicolectomy. Int Surg 1991; : 161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gainant A. Emergency management of acute colonic cancer obstruction. J Visc Surg 2012; : e3–e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gleisner AL, Mogal H, Dodson R et al. Nodal status, number of lymph nodes examined, and lymph node ratio: what defines prognosis after resection of colon adenocarcinoma? J Am Coll Surg 2013; : 1,090–1,100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resch A, Langner C. Lymph node staging in colorectal cancer: old controversies and recent advances. World J Gastroenterol 2013; : 8,515–8,526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fielding LP, Arsenault PA, Chapuis PH et al. Clinicopathological staging for colorectal cancer: an International Documentation System (IDS) and an International Comprehensive Anatomical Terminology (ICAT). J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1991; : 325–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A et al. Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001; : 583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dillman RO, Aaron K, Heinemann FS, McClure SE. Identification of 12 or more lymph nodes in resected colon cancer specimens as an indicator of quality performance. Cancer 2009; : 1,840–1,848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Bowel Cancer Audit Report 2014. London: HQIP; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunnarsson H, Holm T, Ekholm A, Olsson LI. Emergency presentation of colon cancer is most frequent during summer. Colorectal Dis 2011; : 663–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan J, Samaha G, Burke J et al. Emergency presenting colon cancer is an independent predictor of adverse disease-free survival. Int Surg 2015; : 77–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baxter NN, Virnig DJ, Rothenberger DA et al. Lymph node evaluation in colorectal cancer patients: a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; : 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bilchik AJ, Trocha SD. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node analysis to optimize laparoscopic resection and staging of colorectal cancer: an update. Cancer Control 2003; : 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merrie AE, Phillips LV, Yun K, McCall JL. Skip metastases in colon cancer: assessment by lymph node mapping using molecular detection. Surgery 2001; : 684–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gravante G, Elmussareh M. Enhanced recovery for colorectal surgery: practical hints, results and future challenges. World J Gastrointest Surg 2013; : 190–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]