Abstract

Introduction

Anal fistula affects people of working age. Symptoms include abscess, pain, discharge of pus and blood. Treatment of this benign disease can affect faecal continence, which may, in turn, impair quality of life (QOL). We assessed the QOL of patients with cryptoglandular anal fistula.

Methods

Newly referred patients with anal fistula completed the St Mark’s Incontinence Score, which ranges from 0 (perfect continence) to 24 (totally incontinent), and Short form 36 (SF–36) questionnaire at two institutions with an interest in anal fistula. The data were examined to identify factors affecting QOL.

Results

Data were available for 146 patients (47 women), with a median age of 44 years (range 18–82 years) and a median continence score of 0 (range 0–23). Versus population norms, patients had an overall reduction in QOL. While those with recurrent disease had no difference on continence scores, QOL was worse on two of eight SF–36 domains (p<0.05). Patients with secondary extensions had reduced QOL in two domains (p<0.05), while urgency was associated with reduced QOL on five domains (p<0.05). Patients with loose seton had the same QOL as those without seton. No difference in urgency was found between patients with and without loose seton. In primary fistula patients, 19.4% of patients experienced urgency versus 36.3% of those with recurrent fistulas.

Conclusions

Patients with anal fistula had a reduced QOL, which was worse in those with recurrent disease, secondary extensions and urgency. Loose seton had no impact on QOL.

Keywords: Abscess, Quality of life, Rectal fistula

Anal fistula is a track from the anal canal or rectum, with an internal opening that communicates with the skin around the anus at the external opening.1 Approximately 5,000 people undergo anal fistula surgery in the United Kingdom every year; including recurrence gives an incidence of 1:10,000.2 Symptoms include pain, difficulty in sitting and pus/blood discharge when a perianal abscesses is present. Patients may also have systemic sepsis. There are many therapeutic options for anal fistula; however, fistulotomy, which involves division of all tissues encircled by the fistula, has a cure rate of over 90%,3 and is the mainstay of treatment. There is nevertheless a risk of rendering the patient incontinent when the anal sphincter is divided.4-6 Insertion of a loose seton,7 to prevent abscess formation, may be used as bridge to definitive surgery or to control the fistula over the long term; however, this is often associated with a chronic discharge,8 which may itself affect QOL. Should the loose seton be removed, the fistula rarely heals spontaneously.9 Other treatments have a lower cure rate. An appreciation of preoperative QOL with anal fistula is necessary, as surgical treatments may affect continence and subsequent QOL; should the treatment fail, QOL in the case of recurrence is important.

To date, no study has assessed QOL in patients with anal fistula using a robust generic global QOL assessment and an established, validated continence questionnaire. We performed a ‘snapshot’ assessment of QOL in anal fistula patients at presentation using the Short form 36 (SF-36),10 which assesses global health and wellbeing, and the St Mark’s Incontinence Questionnaire, which ranges from 0 (perfect continence) to 24 (totally incontinent).11 We examined whether patients with anal fistula have a reduced QOL, the factors affecting this and their relationship with continence. Urgency, which is defined as the inability to defer defaecation for 15 minutes, is considered to be quite limiting and is weighted on the St Mark’s Incontinence Score with a score of four points. It was therefore examined in greater detail.

Methods

Patients with cryptoglandular anal fistula attending two institutions over 1 year were asked to complete the St Mark’s Incontinence Score and the SF-36 questionnaire at the point of referral. Both institutions are tertiary referral centres for anal fistula and include some patients from the local population. Approval for the study was obtained from the local research ethics committees.

Questionnaires were completed in the majority of cases in the outpatient department, with the remainder on the day of surgery. Information was collected on age, gender, the presence of a seton or a secondary extension branching from the primary track, and any previous surgery. A distinction was made between surgery with curative intent and previous surgery, with all patients who had not undergone curative surgery classified as having a primary fistula. This included those who presented following surgical drainage of an abscess or insertion of a seton, even though, by definition, they had previously undergone anal fistula surgery. Patients who had undergone prior curative surgery were classified as having recurrent fistula.

Statistical analysis

Data from both institutions were pooled for analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare individual SF-36 domains between patients with and without seton, recurrence and secondary extensions. The QOL of patients with and without urgency was compared using the Mann-Whitney U test across all eight domains. To examine the effect of continence on QOL, a simple linear regression analysis using Pearson’s correlation coefficient was performed to compare continence scores with those on each of the SF-36 domains. A negative r value indicates decreasing QOL with increasing incontinence. Finally, Fisher’s exact test was used to determine whether urgency differed with respect to recurrence, secondary extensions or a seton. All analyses were performed using Stats Direct version 2.8.0 (StatsDirect Ltd, Altrincham, UK). Significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

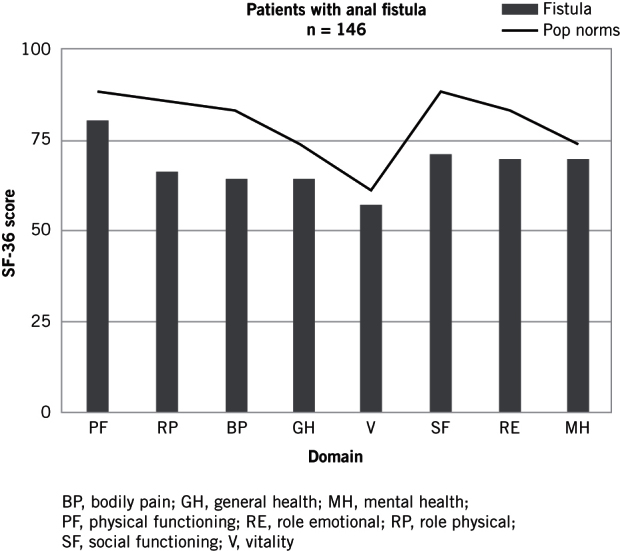

The questionnaires were completed by 146 patients with an anal fistula, of whom 47 were women and 99 men. The median age was 44 (range 18–82 years), and the median continence score for the overall group was 0 (range 0–23). While the raw data from the original study defining the mean population scores for each of the domains are unavailable,10 it can be seen in Figure 1 that anal fistula patients had a reduced QOL compared to the population norm on all domains.

Figure 1.

Mean SF-36 scores

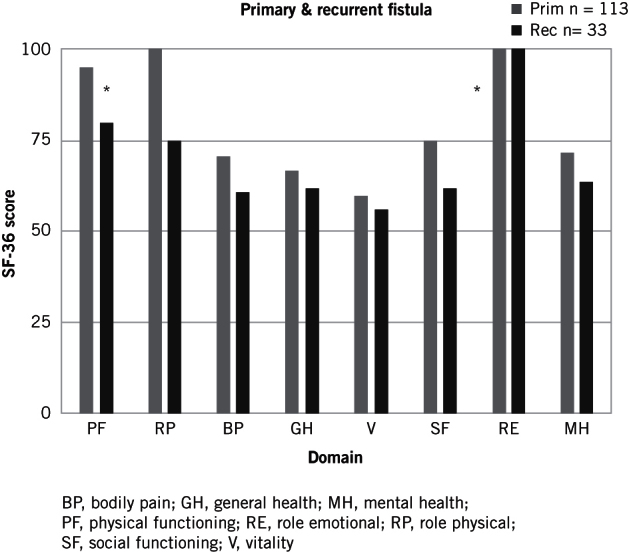

Primary versus recurrent fistulas

One hundred and thirteen patients had primary fistulas, with the remaining 33 patients had recurrent fistulas. The majority of recurrent patients (n=15) had undergone fistulotomy, while seven had received fibrin glue, four an anal fistula plug and three a cutting seton. The remaining three patients had undergone unknown surgery many years previously. There was no significant difference in continence between the primary and recurrent fistula groups, at median scores of 0 (range 0–20) and 0 (range 0–23), respectively. QOL in patients with recurrent disease was significantly worse than that seen in those with a primary fistula on two domains (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Median SF-36 scores in patients with primary and recurrent fistulas

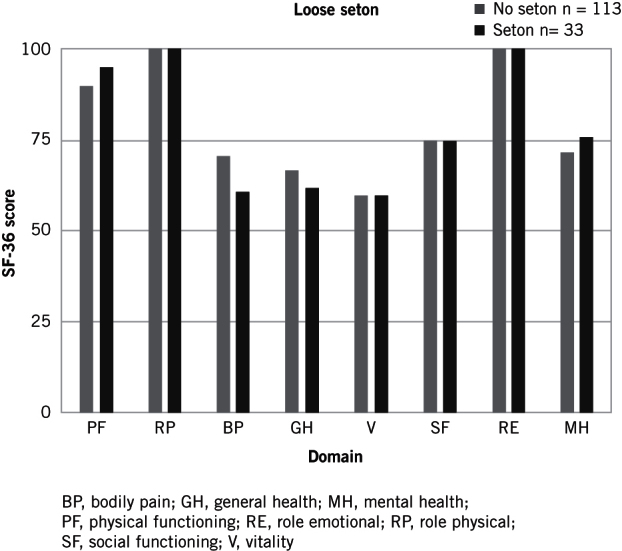

Setons

Prior to referral, 51 patients had undergone insertion of a loose seton. There was no difference in continence scores between those with (median 1; range 0–16) and without a seton (median 0; range 0–23). There were also no differences in SF-36 scores in patients with and without a seton (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Median SF-36 scores in patients with and without a seton

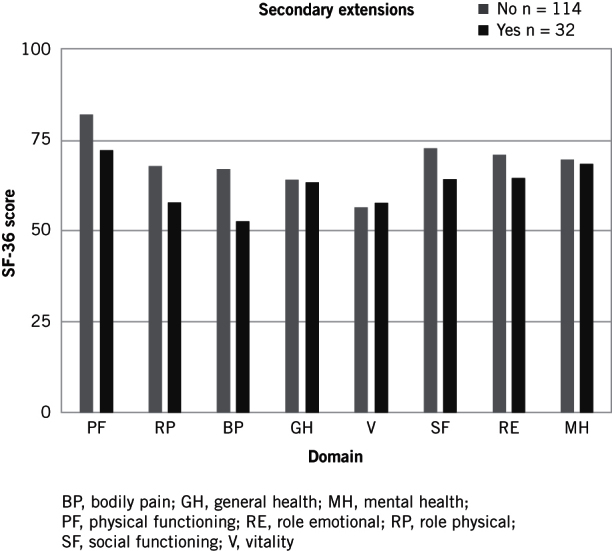

Secondary extensions

Thirty two patients had secondary extensions. There was no difference in continence scores between patients with and without secondary extensions. There was a significant difference in QOL between patients with and without secondary extensions on the Physical Functioning and Bodily Pain domains (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Median SF-36 scores in patients with and without secondary extensions

Continence and QOL

As expected, QOL worsened with increasing incontinence scores (Table 1). However, none of the domains showed a strong correlation with continence score, with a fair correlation found between continence score and the Physical Functioning domain.

Table 1.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient between continence score and SF-36 domains

| Domain | PF | RP | BP | GH | V | SF | RE | MH |

| r value | -0.33 * | -0.11 | -0.23* | -0.2* | -0.23* | -0.21 * | -0.15 | -0.11 |

*p<0.05.

BP, bodily pain; GH, general health; MH, mental health; PF, physical functioning; RE, role emotional; RP, role physical; SF, social functioning; V, vitality.

Urgency

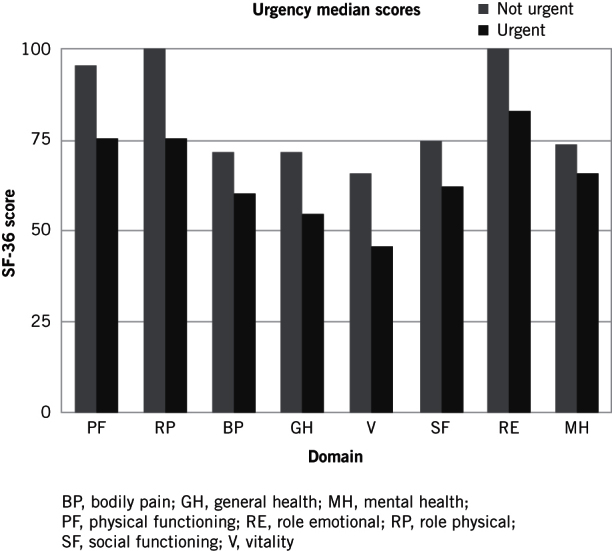

Thirty four (23.3%) patients had urgency, with a median continence score of 11 (range 4–23). There was no significant difference in age between patients with and without urgency. A significant difference was found on five SF-36 domains between patients with and without urgency (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Median SF-36 scores in patients with and without urgency

Further subgroup analysis revealed that there was no significant difference in the number of patients with urgency in the primary and recurrent fistula groups, at 22 (19.4%) versus 12 (36.3%). Similarly, no significant difference in urgency was found between patients with and without a seton, or those with and without secondary extensions.

Discussion

This study was designed as a snapshot QOL assessment of patients with anal fistula to aid decision-making in this often difficult-to-treat disease. Although fistulotomy carries a risk of reducing continence, alternatives approaches have varying rates of cure. For example, cutting seton has a recurrence rate of 0%–28%,12,13 and an incontinence rate of 20%–77%,12,14 while the ‘sphincter sparing’ advancement flap technique has a recurrence rate of between 25% and 65% and an incontinence rate of 30%.15 The Surgisis Biodesign Fistula Plug (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) is associated with recurrence rates of between 17% and 86% and an incontinence rate of approaching zero,16,17 while the ligation of fistula track procedure has yielded recurrence rates of 5%–60% and a incontinence rate of 6%.18

The data in this study were collected prospectively. Using validated QOL and continence assessment tools,10,11 a trend was seen for worse QOL in anal fistula patients versus population norms. Patients with recurrent fistulas had reduced QOL compared to those wit primary fistula. This was contrary to the findings of a previous report,19 and may reflect the tertiary nature of the patient group studied. QOL was worse in fistulas with secondary extensions than in those with a single track. Patients with a loose seton had the same QOL as those without, suggesting that definitive treatment with a loose seton may not improve QOL.

There has been some previous research examining QOL in anal fistula; one study indicated that people with anal fistula did not have reduced QOL compared to age-matched healthy individuals.20 In this work, a variety of benign anorectal disorders, including anal fistula, were assessed using the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI). The GIQLI was developed from patients with pathologies higher in the gastrointestinal tract, such as peptic ulceration and biliary disease, and is thus not an accurate assessment for anal fistula. It has therefore been argued that different questions need to be asked in anal disease,21 Faecal incontinence is known to have a detrimental impact on QOL,22 and it has been suggested that QOL following fistula surgery strongly correlates with reduced faecal continence.19,23,24 QOL with recurrent disease needs to be balanced against the QOL associated with reduced continence. The Fecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI) was devised,25 validated,23 and then used to predict QOL following fistula surgery,24 which indicated that QOL is strongly correlated with FISI scores.

In our study, no overall correlation was found between continence score and QOL; however, urgency was found to have a significant impact on QOL. Patients with urgency had a reduced QOL compared to those without across five of the eight SF-36 domains: Physical Functioning, Role-Physical, General Health, Vitality and Social Functioning; ie, those domains that reflect physical functioning and social activity. In primary fistulas, one in five patients experienced urgency, compared to one in three of recurrent fistula patients.

Traditionally, loose draining setons have been used to reduce the risk of deteriorating continence following fistulotomy.26,27 The rationale for this is to facilitate drainage and thus avoid recurrent septic episodes and abscess formation. Our data, however, suggest that, while a loose seton does not involve sphincter division, there was no difference in QOL between patients with and without a seton, and no significant difference in urgency. What cannot be ascertained from our data, however, was how many of the seton population may have developed abscesses were the seton not in place, nor whether QOL changes with seton insertion.

Conclusions

Patients with recurrent disease and those with urgency may accept a higher risk of postoperative incontinence with fistulotomy in exchange for a higher chance of cure than other treatments. However, further work is needed to solve this on-going dilemma. No correlation was found between continence score and QOL. Using continence as a surrogate outcome for QOL in fistula surgery therefore runs the risk of patients not receiving curative surgery through fear of minor continence disturbance, whereas QOL may be improved over that experienced by living with a fistula.

References

- 1.Marks CG, Ritchie JK. Anal fistulas at St Mark’s Hospital. Br J Surg 1977; : 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ewerth S, Ahlberg J, Collste G et al. Fistula-in-ano. A six year follow up study of 143 operated patients. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1978; : 53–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shouler PJ, Grimley RP, Keighley MR et al. Fistula-in-ano is usually simple to manage surgically. Int J Colorectal Dis 1986; : 113–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lunniss PJ, Kamm MA, Phillips RK. Factors affecting continence after surgery for anal fistula. Br J Surg 1994; : 1,382–1,385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Aguilar J, Belmonte C, Wong WD et al. Anal fistula surgery. Factors associated with recurrence and incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; : 723–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mylonakis E, Katsios C, Godevenos D et al. Quality of life of patients after surgical treatment of anal fistula; the role of anal manometry. Colorectal Dis 2001; : 417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson JP, Ross AH. Can the external anal sphincter be preserved in the treatment of trans-sphincteric fistula-in-ano? Int J Colorectal Dis 1989; : 247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy HL, Zegarra JP. Fistulotomy without external sphincter division for high anal fistulae. Br J Surg 1990; : 898–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan GN, Owen HA, Torkington J et al. Long-term outcome following loose-seton technique for external sphincter preservation in complex anal fistula. Br J Surg 2004; : 476–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L. Short form 36 (SF36) health survey questionnaire: normative data for adults of working age. BMJ 1993; : 1,437–1,440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA et al. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut 1999; : 77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durgun V, Perek A, Kapan M et al. Partial fistulotomy and modified cutting seton procedure in the treatment of high extrasphincteric perianal fistulae. Dig Surg 2002; : 56–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasegawa H, Radley S, Keighley MR. Long-term results of cutting seton fistulotomy. Acta Chir Iugosl 2000; : 19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graf W, Pahlman L, Ejerblad S. Functional results after seton treatment of high transsphincteric anal fistulas. Eur J Surg 1995; : 289–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schouten WR, Zimmerman DD, Briel JW. Transanal advancement flap repair of transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 1999; : 1419–22; discussion 1,422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawes DA, Efron JE, Abbas M et al. Early experience with the bioabsorbable anal fistula plug. World J Surg 2008; : 1,157–1,159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Champagne BJ, O’Connor LM, Ferguson M et al. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 2006; : 1,817–1,821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yassin NA, Hammond TM, Lunniss PJ et al. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract in the management of anal fistula. A systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2013; : 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Aguilar J, Davey CS, Le CT et al. Patient satisfaction after surgical treatment for fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; : 1,206–1,212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sailer M, Bussen D, Debus ES et al. Quality of life in patients with benign anorectal disorders. Br J Surg 1998; : 1,716–1,719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guest M, Smith JJ, Davies AH. Quality of life in patients with benign anorectal disorders. Br J Surg 1999; : 843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothbarth J, Bemelman WA, Meijerink WJ et al. What is the impact of fecal incontinence on quality of life? Dis Colon Rectum 2001; : 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW et al. Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; : 9–16; discussion 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavanaugh M, Hyman N, Osler T. Fecal incontinence severity index after fistulotomy: a predictor of quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; : 349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence: the fecal incontinence severity index. Dis Colon Rectum 1999; : 1,525–1,532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malouf AJ, Buchanan GN, Carapeti EA et al. A prospective audit of fistula-in-ano at St. Mark’s hospital. Colorectal Dis 2002; : 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joy HA, Williams JG. The outcome of surgery for complex anal fistula. Colorectal Dis 2002; : 254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]