Dear Editor,

Carriers of balanced chromosomal rearrangements, including reciprocal, robertsonian translocations, and inversions, have all genetic information conserved. Nevertheless, because of the possibility of defect in chromosome segregation during gametogenesis, carriers of balanced rearrangements have an increased risk of spontaneous abortion and/or a chromosomally unbalanced child with intellectual deficiency or multiple congenital malformations. Unbalanced translocations in patients with normal phenotype are rarely described. Only three unbalanced translocations involving acrocentric chromosome with meiotic defects were reported in the literature in infertile men.1,2,3

Here, we report a 39-year-old healthy patient referred to Assisted Reproductive Laboratory for infertility. The patient and his partners present a history of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss (RPL) (6 with the first partner and 3 with his current partner). On physical examination, the patient was phenotypically normal, he has no developmental abnormalities, and the medical history revealed no early neonatal problems and no motor impairment. The semen analysis performed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2010 showed normal parameters (volume: 2.5 ml, pH: 7.9, concentration: 15 × 106 spermatoza ml−1, progressive motility: 40%, immotile: 2%, normal form: 5% (Kruger's criteria) and familial reproductive history failed to show developmental abnormalities or repeated abortion.4 There is no hormonal alteration. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), inhibin, and prolactin levels were in the normal range.

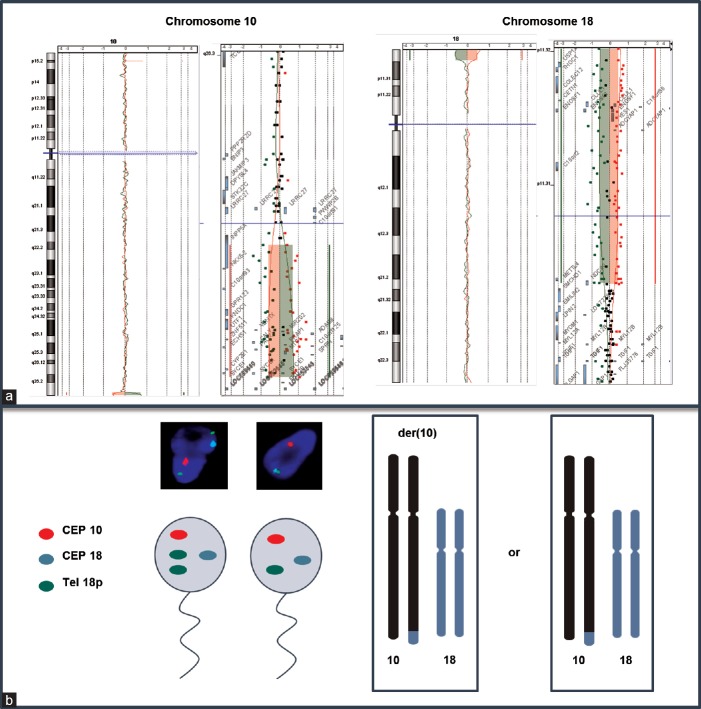

Cytogenetic analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes revealed a normal karyotype. Subtelomeric-Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) highlighted a derivative chromosome 10 (der(10)) from unbalanced translocation involving the long arm of chromosome 10 and the short arm of chromosome 18. This unbalanced translocation-generated partial 10q monosomy and partial 18p trisomy. Twenty-eight percent of 1000 spermatozoa scored by triple-color FISH analysis exhibited an unbalanced chromosomal equipment corresponding to the presence of the der(10) able to generate the same karyotype than the patient and 72% of balanced spermatozoa (Figure 1). No further rearrangement involving chromosome 10 and 18 has been found. Hybridization with X, Y, 18, 13, and 21 chromosome probes revealed no significant increase of gametes with numerical abnormalities (data not shown). Microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization was performed using Agilent® oligonucleotide arrays according to the manufacturer's instruction (Agilent Human Genome CGH Microarray kit 4x180K®, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). Microarray confirmed a 1-Mb 10q26.3-10qter deletion extending from base 134 427 068 to base 135 434 178 and a 2.5-Mb 18p11.32-18pter amplification extending from base 118 760 to base 2 671 435 according to National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (build 37-hg19).

Figure 1.

Molecular characterization of derivative chromosome 10. (a) Microarray shows a 1 Mb deletion in 10q26.3-10qter region and a 2,5-Mb amplification in 18p11.32-18pter. (b) Sperm triple-color FISH analysis for chromosome 10 and 18 with normal spermatozoa (right), unbalanced gamete carrying the derivate chromosome 10 (left) and hypothesized chromosome bivalent pairing.

Chromosomal reorganization may affect the proper progression of gametogenesis disrupting homologous chromosome pairing. In unbalanced translocation, pairing of homologous region and formation of quadrivalent are not possible, and the consequences of meiotic segregation are unclear. To provide a better understanding of the consequences of the der(10) on gametogenesis and try to explain reproductive disorders reported in our patient, a study of meiotic segregation by sperm-FISH was performed. Taking into account the reduced size of unbalanced region, we hypothesized the formation of a bivalent during meiosis. As expected, sperm-FISH showed 72% balanced haploid cells, 28% haploid cells with 10q subtelomeric nullosomy and 18p subtelomeric disomy corresponding to the der(10), suggesting no consequence in the offspring, except the presence of the paternal derivative chromosome.

Three unbalanced translocations involving acrocentric chromosomes in infertile patients have been reported so far. In these previously published cases, translocations involved large parts of chromosome with formation of a trivalent configuration at meiosis between the derivative and acrocentric chromosomes with an asynapsed region.1,2,3 The trivalent can produce alternate or adjacent mode of segregation and may, therefore, explain RPL. In the current study, sperm-FISH results confirmed the absence of new unbalance generated during meiosis.

However, we cannot exclude that these unbalances which may compromised fertility can produce disturbances in the proper segregation of other chromosome pairs called as interchromosomal effect (ICE), favoring with the formation of numerical abnormalities in the resulting gametes. Nevertheless, the occurrence and distribution of these disturbing events still are a controversial issue.5 The presence of ICE in this case seems to be unlikely taking into account the absence of significant increase of gametes with numerical abnormalities X, Y, 13, 18, and 21 chromosomes, and the cytogenetics results of the father who shares the same derivative chromosome have no reproductive disorder.

The development and the clinical applications of microarrays in the past few years have revolutionized the diagnostic work-up of patient with developmental delay and facilitated the identification of the molecular basis of many genetic diseases.5 In contrast, the reported use of microarray for studying reproductive disorders is still limited in comparison with its widespread use to test patients with developmental delay/congenital abnormalities, preimplantation embryos, and ongoing pregnancies.6,7 Uncovering new genetic causes of impaired reproduction, with new molecular tools such as microarray and screening for their recurrence in additional affected patients, will lead to an improved understanding of their role in reproduction and more informed clinical management.

Partial 10q monosomy is a rare cytogenetic abnormality with distinctive phenotype including abnormal facial shape, cardiac and urogenital anomalies, neurodevelopmental disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders (ADHD) susceptibility.8 A Smallest Region of Overlapping (SRO) has been proposed with DOCK1 as the main candidate gene.9 The 10q monosomy reported here is distal to the SRO. This deletion spans over 1-Mb and encompassed 22 genes. Among these genes, they are all involved in general cellular process, except for CALY gene that have been recently reported in human disease as a possible candidate gene for ADHD.9 However, the patient and his father showed no behavioral difficulties, suggesting a potential incomplete penetrance and other genetics and/or epigenetics factors.

In addition, most of the pure trisomies of the whole chromosome 18p reported have been identified by conventional cytogenetic methods. Whole 18p trisomies are phenotypically heterogeneous with subtle dysmorphic features and moderate intellectual disabilities; however, some cases are presented with normal phenotype and no intellectual disability.10 The 18p amplification spanned over 2,5-Mb encompassing 13 genes including SMCHD1 (OMIM 614982), associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, a recessive developmental disorder. Finally, among the genes encompassed in both deleted and duplicated region, none are associated with developmental delay or seems to play a role in spermatogenesis.

Sperm-FISH is a widely used screening tool to aid in counseling couples with severe male factor infertility, especially in cases of repeated failed fertilization by assisted reproductive technologies or RPL. Not well establish in human reproduction, microarray analysis provides a more comprehensive view of the genome with new opportunities to find or exclude a chromosomal origin of miscarriage and reproductive disorders. In this study, information gathered from sperm-FISH and microarray allowed us to confirm the absence of meiotic defects in the presence of such a derivative chromosome and enabled us to refine 18p and 10q subtelomeric regions which are phenotypically silent in case of unbalances.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SK performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript. EP performed microarray. CF collected the clinical information. PV, AT, and CG participated in the critical discussion. FB, LJ, and CPR revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declared no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perrin A, Douet-Guilbert N, Laudier B, Couet ML, Guérif F, et al. Meiotic segregation in spermatozoa of a 45, XY,-14, der(18)t(14;18) (q11;p11.3) translocation carrier: a case report. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:729–32. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leclercq S, Auger J, Dupont C, Le Tessier D, Lebbar A, et al. Sperm FISH analysis in two healthy infertile brothers with t(15;18) unbalanced translocation: implications for genetic counselling and reproductive management. Eur J Med Genet. 2010;53:127–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng DH, Gong F, Lu CF, Li LY, Lu GX, et al. Risk evaluation and preimplantation genetic diagnosis in an infertile man with an unbalanced translocation t(10;15) resulting in a healthy baby. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29:1299–304. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9857-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. 5th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munné S, Escudero T, Fischer J, Chen S, Hill J, et al. Negligible interchromosomal effect in embryos of robertsonian translocation carriers. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;10:363–9. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61797-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang JU, Koo SH. Evolving applications of microarray technology in postnatal diagnosis. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30:223–8. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colls P, Escudero T, Fischer J, Cekleniak NA, Ben-Ozer S, et al. Validation of array comparative genome hybridization for diagnosis of translocations in preimplantation human embryos. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;24:621–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yatsenko SA, Kruer MC, Bader PI, Corzo D, Schuette J, et al. Identification of critical regions for clinical features of distal 10q deletion syndrome. Clin Genet. 2009;76:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plaisancié J, Bouneau L, Cances C, Garnier C, Benesteau J, et al. Distal 10q monosomy: new evidence for a neurobehavioral condition? Eur J Med Genet. 2014;57:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orendi K, Uhrig S, Mach M, Tschepper P, Speicher MR. Complete and pure trisomy 18p due to a complex chromosomal rearrangement in a male adult with mild intellectual disability. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161:1806–12. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]