Abstract

Objectives. To estimate the lifetime prevalence of official investigations for child maltreatment among children in the United States.

Methods. We used the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System Child Files (2003–2014) and Census data to develop synthetic cohort life tables to estimate the cumulative prevalence of reported childhood maltreatment. We extend previous work, which explored only confirmed rates of maltreatment, and we add new estimations of maltreatment by subtype, age, and ethnicity.

Results. We estimate that 37.4% of all children experience a child protective services investigation by age 18 years. Consistent with previous literature, we found a higher rate for African American children (53.0%) and the lowest rate for Asians/Pacific Islanders (10.2%).

Conclusions. Child maltreatment investigations are more common than is generally recognized when viewed across the lifespan. Building on other recent work, our data suggest a critical need for increased preventative and treatment resources in the area of child maltreatment.

Child maltreatment, including neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse, is a risk factor for myriad negative health outcomes in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Negative outcomes linked to child maltreatment include degraded neurologic capacity to deal with stress,1 worsened general physical health,2 elevated levels of risky health behaviors,2 mental health problems,2,3 impaired intellectual and cognitive development,3,4 increased violent and criminal behaviors5 and increased mortality through adulthood.2,6,7 A recent estimate of total lifetime cost for a single year of US children with investigated maltreatment reports was about $585 billion (in 2010 US dollars), which is equivalent to almost 4% of the US gross domestic product in 2010.8

Accurately assessing lifetime exposure to child maltreatment is a crucial first step in better understanding and responding to child maltreatment, but most large studies and existing data sets assess maltreatment during only a single-year time frame.9,10 There are 2 notable exceptions. Sabol et al. estimated that from birth to age 10 years within Cuyahoga County (Cleveland), Ohio, 31.0% of children were investigated by child protective services (CPS) for maltreatment concerns and 19.5% of children were found to have sufficient evidence to legally substantiate maltreatment from CPS investigations.11 Wildeman et al. estimated the lifetime child maltreatment prevalence for US children as 12.5% by age 18 years, but considered only child maltreatment reports substantiated by CPS.12 Substantiated reports are a small subset of all reports. In 2014, only 21.9% of investigated reports were substantiated.10 (Technically, “investigated” indicates “investigated or assessed” and “substantiated” indicates “substantiated or indicated” here and after.)

A large and growing literature demonstrates that many unsubstantiated reports involve high-risk situations.13 Many researchers assert that legal substantiation of investigated reports by CPS is unreliable.13,14 Research shows that children with substantiated investigations are virtually indistinguishable from those who are unsubstantiated in a wide range of subsequent negative outcomes ranging from child maltreatment re-report to school achievement to mortality.14,15 For these reasons, many recent studies use the “any investigation” metric exclusively16 whereas others have presented both substantiated investigations and total investigations as separate counts.8

Another key aspect of child maltreatment research is the timeframe used. Although very few administrative data studies have used long timeframes, there have been retrospective studies done in which older children or young adults are asked to recount their maltreatment experiences across several years. These retrospective studies are not without problems—most notably, issues with accurately recalling events from many years ago or before the offset of childhood amnesia.2 This is problematic given the hypothesized serious neurologic and health impacts of very early maltreatment.1 The most recent wave of the 3 National Surveys of Children’s Exposure to Violence estimated that 38.1% of children had experienced maltreatment through age 17 years.17 The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health surveyed young adults in 2001–2002 and found a lifetime maltreatment prevalence of 41.5% for supervision neglect, 11.8% for physical neglect, 28.4% for physical assault, and 4.5% for sexual abuse.18

The purpose of this study is to provide a scientifically conservative estimate for lifetime cumulative risk of maltreatment investigations by CPS among US children. The current study extends previous work by Wildeman et al.12 by (1) including all maltreatment investigations rather than only substantiated investigations; (2) providing the first, to our knowledge, type-specific (i.e., neglect, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse) estimates; and (3) using a novel methodology to identify true first-time events. We estimate, for the first time to our knowledge, age-specific cumulative risks of maltreatment investigations from birth through age 17 years for US children. Cumulative risks of substantiated investigations (following Wildeman et al.12) are also estimated for purposes of comparison.

METHODS

We obtained maltreatment data from the 2003–2014 National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child Files,19 the national repository for child maltreatment reports to CPS in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories. The CPS agencies exist in every state and accept reports from professionals (mandated reporters) and nonprofessionals (nonmandated in most states). The annual Child File data releases include a range of descriptors about investigated maltreatment reports, including maltreatment type, date, perpetrator, family characteristics, and services provided. Reported but screened out (i.e., not accepted or investigated) cases are not included in the Child File. We obtained child population data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).20 Because maltreatment data were based on the federal fiscal year (FFY), we interpolated population data to the midpoint of each FFY (hereafter, all years are FFY).

In 2014, the estimated child population in 50 states and District of Columbia was 73 590 265. The 2014 Child File includes 3 180 249 investigated maltreatment reports, representing 2 666 677 unique children. About 7 in 1000 investigations were missing child age. We dropped these cases from the analysis. The following 7 states have missing year observations between 2004 and 2014—Connecticut, Idaho, Maryland, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Oregon—making it possible that first or subsequent investigations would be missed. We therefore excluded those states, resulting in a loss of about 9% of the US child population.

Measures

We used child age (in years), gender, race/ethnicity, and maltreatment type from the NCANDS Child Files. Race/ethnicity is coded as follows: first, Native American is coded whenever indicated; second, Hispanic is coded when indicated among non-Native Americans; and finally, a child is coded as Black, White, or Asian/Pacific Islander when such is uniquely indicated. We extracted race/ethnicity–specific child populations from the CDC data in a manner corresponding to this coding. About 4.5% of investigations indicated more than 1 racial group with no indication of Native American or Hispanic heritage and about 8.6% had missing information on race/ethnicity. These were excluded from race/ethnicity specific estimates (only). We measured 4 major types of maltreatment: neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. About 19% of investigations involved unknown or other types of maltreatment, and were excluded from type-specific estimates (only). Gender (i.e., male or female) was missing in 0.5% of investigations and we excluded these cases from gender-specific estimates (only).

We applied a period (or “synthetic”) life table method.21 We estimated the probability of ever having a child maltreatment investigation during the lifetime (age 0–17 years) of a hypothetical birth cohort by assuming that the cohort lived through estimated age-specific risks by the period life table based on age-specific first-time investigation rates in a single year period (i.e., 2014). We computed the age-specific first-time investigation rates by dividing the age-specific number of first-time investigated children in 2014 (from NCANDS) by the age-specific population in 2014 (from CDC).

For greater accuracy, we employed 2 innovations. First, we made substantial efforts to locate children with a true first-time investigation among total investigated children in 2014. This process is important because inclusion of non–first-time investigations results in overestimation of the age-specific first-time risks and eventually leads to overestimation of cumulative risk (i.e., risk of ever having an investigation). We describe our approach to this problem in the following section.

Second, with regard to accurately determining what proportion of the population had had no previous investigation and was thus “at risk” for a first-time investigation, we reduced each age-specific population to reflect children investigated before the age in question. (A full life table is presented in Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.) We used Greenwood’s method to estimate standard errors of cumulative risks.22

A potential vulnerability of this period life table method is that its estimates would be unreliable if annual age-specific rates are unstable over time. Fortunately, annual age-specific rates were reasonably consistent among each of the 2003–2014 NCANDS Child Files. We therefore used the latest year’s data (i.e., 2014) to maximize the chance of locating true first-time investigated children among all investigated children in 2014 by utilizing previous years’ data. Type-specific first-time investigations were located on the basis of previous allegations of that particular type of maltreatment. Similarly, we counted first-time substantiated investigations among only substantiated investigations.

Locating First-Time Events

In previous work limited to substantiated cases, Wildeman et al.12 were able to locate first-time substantiated investigations from total substantiated investigations because the Child File includes the variable “CHPRIOR.” This indicates whether a currently investigated child had a previous substantiated investigation. Unfortunately, no similar variable exists for previous nonsubstantiated investigations. We therefore used the following approach to determine which children genuinely had a first-time investigation among total investigated children in 2014.

First, we linked all the annual files across time (2003–2014 NCANDS Child Files19) by unique child identifiers to form a single longitudinal database. We did not include earlier Child Files because of quality issues involving missing data. We located investigated children in 2014 with no previous investigation in the database (i.e., database-first-time investigated children). At this point, we were still vulnerable to left censoring for older children. That is, among the database-first-time investigated children, those aged 11 years or older could possibly have had investigations before 2003. This required us to adjust (i.e., reduce) the age-specific number of database-first-time investigated children by their age-specific probability of having database-unobserved previous investigations.

For this adjustment involving database-unobserved investigations, we used information from substantiated investigations in which database-unobserved previous substantiations were captured by the variable “CHPRIOR.” That is, we adjusted the age-specific number of database-first-time investigated children by the age-specific probability of CHPRIOR equal to 1 (i.e., having a previous substantiation) among the database-first-time substantiated children in 2014. We estimated this age-specific probability for each type–gender–race/ethnicity combination (e.g., Hispanic females with neglect concerns) to conduct the best possible adjustment for each combination (see Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for details).

In this adjustment, we assumed that the unobserved age-specific probabilities for investigations were similar to those observed by CHPRIOR for substantiations. Given the higher recidivism risk of investigations than that of substantiations, one may question the credibility of this assumption. However, the difference in recidivism risk works in 2 opposite directions: (1) a larger chance of having an investigation 12 or more years earlier (i.e., outside the database coverage) than of having substantiation and (2) a larger chance of having a previous investigation within the database coverage than of having substantiation.

We checked our assumption by examining how these reversed functions were canceled out in our database. We compared investigations and substantiations with regard to the age-specific proportions having the closest previous event 10 or more years back (i.e., having a previous event in 2003–2004, but no previous event in 2005–2013) among older (aged 10–17 years) children with non–first-time events in 2014. If these proportions are similar between investigations and substantiations, our assumption becomes more credible. The proportions were, on average, 3.7% (SD = 0.5) for investigations versus 6.1% (SD = 0.7) for substantiations (see Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for detail). The slightly larger proportions for substantiations suggested that our adjustment might lead to slight underestimation of the age-specific number of true first-time investigated children rather than overestimation.

We further evaluated the accuracy of our adjustment method by various supplementary tests masking (omitting) early years’ data from the original 2003–2014 database (Figure B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). This evaluation showed that, when at least 7 years of data are included, the estimates become very stable (< 1-percentage-point variance from original estimate).

We explored 3 other estimation methods to be certain that the adjustment method we ultimately used was most appropriate. All alternative estimates were slightly higher (less conservative) than the estimates based on our adjustment method (see Figure C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for details).

RESULTS

In 2014, 4.57% of all US children had a maltreatment investigation (Table 1). Of these, about half (2.39%) had no previous investigation in the 2003–2014 database. After adjusting for database-first-time investigation rates as described in the preceding section, we estimate that 2.09% had a true first-time investigation (hereafter, “first-time” refers to the adjusted estimate). Annualized rates of first-time investigations in 2014 varied by race, being notably higher for Blacks (3.46%), and notably lower for Asians/Pacific Islanders (0.57%). Girls had a slightly higher rate of a first-time investigation (2.11%) than boys (2.04%). First-time investigation rates were highest for neglect (1.40%), followed by physical abuse (0.64%), sexual abuse (0.23%), and emotional abuse (0.20%). For substantiated investigations, 0.65% of all US children had a first-time event.

TABLE 1—

Demographics of US Children Aged 0 to 17 Years With Investigated and Substantiated Child Maltreatment, 2014

| Maltreatment Investigation, No. in 1000s (%) |

Substantiated Investigation, No. in 1000s (%) |

||||||

| Variable | Child Population, No. in 1000s | All | First Time | Adjusted First Time | All | First Time | Adjusted First Time |

| Total | 66 769 | 3 052 (4.57) | 1598 (2.39) | 1 398 (2.09) | 686 (1.03) | 496 (0.74) | 437 (0.65) |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 35 760 | 1 347 (3.77) | 656 (1.84) | 556 (1.55) | 292 (0.82) | 207 (0.58) | 176 (0.49) |

| Black | 9 896 | 652 (6.59) | 342 (3.46) | 297 (3.00) | 153 (1.55) | 110 (1.11) | 96 (0.97) |

| Hispanic | 16 209 | 618 (3.82) | 320 (1.98) | 294 (1.81) | 157 (0.97) | 112 (0.69) | 104 (0.64) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 783 | 32 (0.85) | 23 (0.60) | 21 (0.57) | 7 (0.19) | 6 (0.16) | 6 (0.15) |

| Native American | 1 122 | 45 (4.01) | 18 (1.58) | 15 (1.32) | 12 (1.03) | 8 (0.67) | 6 (0.56) |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 34 106 | 1 524 (4.47) | 798 (2.34) | 696 (2.04) | 338 (0.99) | 244 (0.72) | 215 (0.63) |

| Female | 32 664 | 1 511 (4.63) | 786 (2.41) | 688 (2.11) | 345 (1.06) | 249 (0.76) | 219 (0.67) |

| Subtype | |||||||

| Neglect | 66 769 | 1 868 (2.80) | 1 068 (1.60) | 937 (1.40) | 441 (0.66) | 331 (0.50) | 293 (0.44) |

| Physical | 66 769 | 656 (0.98) | 493 (0.74) | 427 (0.64) | 93 (0.14) | 85 (0.13) | 75 (0.11) |

| Sexual | 66 769 | 211 (0.32) | 177 (0.27) | 151 (0.23) | 44 (0.07) | 41 (0.06) | 35 (0.05) |

| Emotional | 66 769 | 194 (0.29) | 152 (0.23) | 131 (0.20) | 28 (0.04) | 25 (0.04) | 22 (0.03) |

Note. Adjusted first time = adjusted first-time events; first time = database-first-time events; investigated = investigated or assessed; substantiated = substantiated or indicated. Totals may be not equal to sums of subcategories because of the rounding errors, missing values, and excluded categories. Among all maltreatment investigations, 0.55% were unknown for gender, 8.6% for race, and 13.0% for maltreatment type. Multiracial children (3.1%) and other type of maltreatment (5.9%) are not listed in subcategories. A sum of maltreatment subtypes can go over a total because a child may have multiple subtypes in an investigation.

Source. All maltreatment data are from the 2003–2014 National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System Child Files,19 and all population data are based on “bridged-race population estimates 1990–2014” data requested from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER online database, which draws from US Census data.20

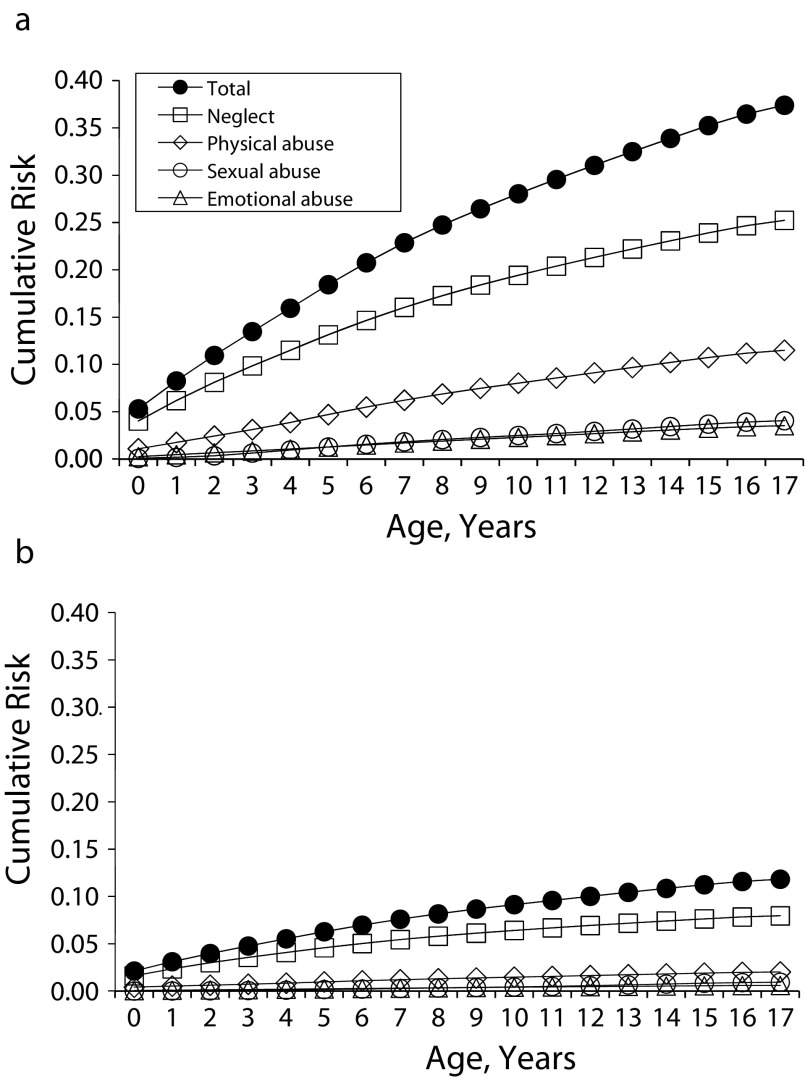

We estimated age-specific cumulative risks on the basis of the (adjusted) first-time events in 2014 and presented them in Figure 1. (They are also available as numbers in Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.) The cumulative rate of maltreatment investigations was 5.3% (99.9% confidence interval [CI] = 5.3%, 5.3%) at age 0 and increased to 37.4% (99.9% CI = 37.3%, 37.5%) at age 17 years. By subtype, the cumulative risk through age 17 years was 25.2% (99.9% CI = 25.2%, 25.3%) for neglect, 11.5% (99.9% CI = 11.4%, 11.6%) for physical abuse, 4.1% (99.9% CI = 4.0%, 4.1%) for sexual abuse, and 3.5% (99.9% CI = 3.5%, 3.6%) for emotional abuse. The cumulative risk for substantiated investigations was 11.8% (99.9% CI = 11.8%, 11.9%) at age 17 years. Sexual abuse risk tended to be proportionately higher in later childhood compared with other subtypes.

FIGURE 1—

Cumulative Risk of Maltreatment That Was (a) Investigated and (b) Substantiated: United States, 2014

Source. All maltreatment data are from the 2003–2014 National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System Child Files,19 and all population data are based on “bridged-race population estimates 1990–2014” data requested from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER online database, which draws from US Census data.20

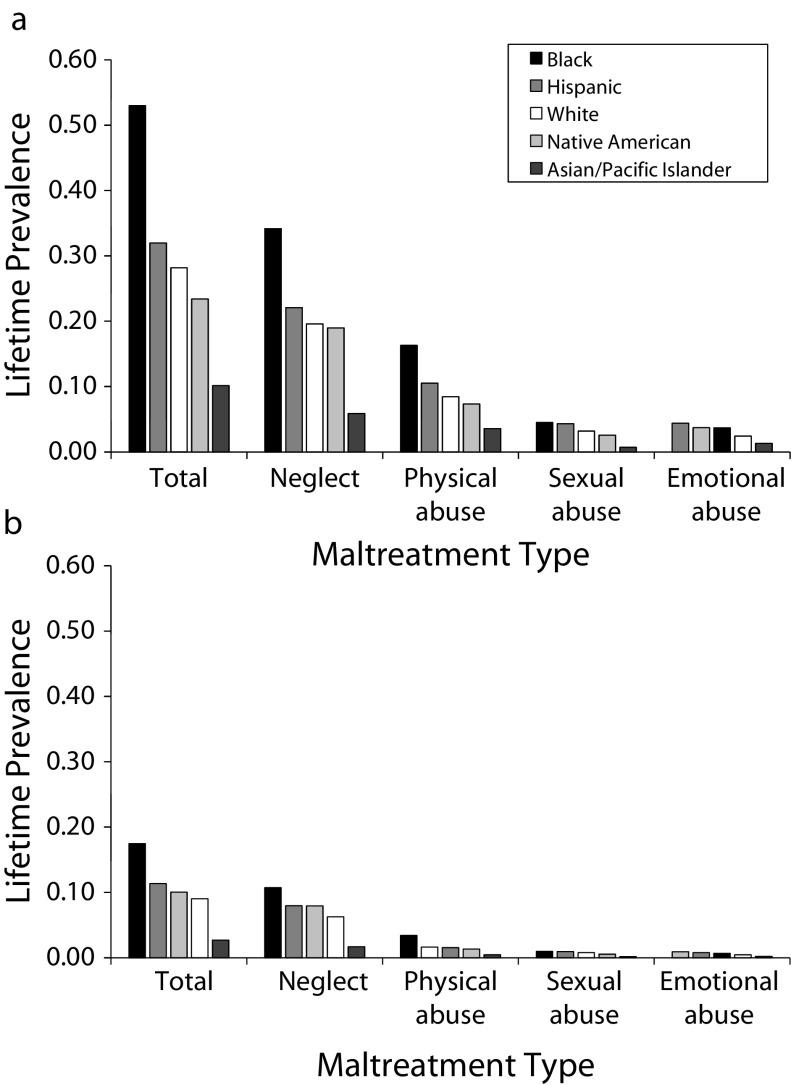

Age-specific patterns of cumulative risks by race/ethnicity and gender are available in Figures D–G (available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). For those who are interested in the onset of total and subtype maltreatment investigations and substantiations, we also provide age-specific risks (i.e., hazard functions) by race/ethnicity and gender (Figures H–K, available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Here, we present only cumulative risks at age 17 years (i.e., lifetime prevalence) by race/ethnicity (Figure 2) and gender (Figure 3). Black children had the highest lifetime prevalence of maltreatment investigations at 53.0% (99.9% CI = 52.8%, 53.2%), followed by 32.0% (99.9% CI = 31.8%, 32.1%) for Hispanics, 28.2% (99.9% CI = 28.1%, 28.3%) for Whites, 23.4% (99.9% CI = 22.9%, 24.0%) for Native Americans, and 10.2% (99.9% CI = 9.9%, 10.4%) for Asians/Pacific Islanders. By maltreatment types, this order was maintained and significant at P < .001 except for emotional abuse. Hispanic children showed the highest lifetime prevalence for investigated emotional abuse reports, followed by Native American, Black, White, and Asian/Pacific Islander children. All differences in emotional abuse were significant at P < .001 except that between Native Americans and Blacks.

FIGURE 2—

Lifetime Prevalence by Race/Ethnicity of Maltreatment That Was (a) Investigated and (b) Substantiated: United States, 2014

Source. All maltreatment data are from the 2003–2014 National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System Child Files,19 and all population data are based on “bridged-race population estimates 1990–2014” data requested from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER online database, which draws from US Census data.20

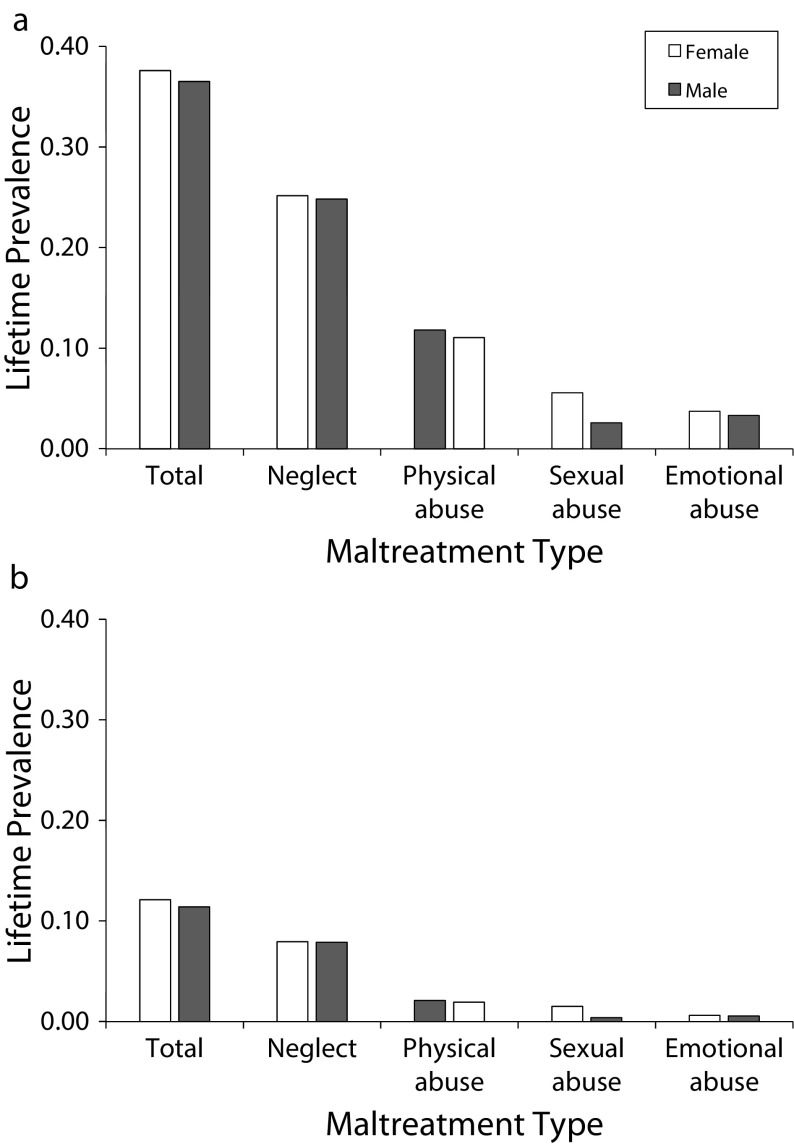

FIGURE 3—

Lifetime Prevalence by Gender of Maltreatment That Was (a) Investigated and (b) Substantiated: United States, 2014

Source. All maltreatment data are from the 2003–2014 National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System Child Files,19 and all population data are based on “bridged-race population estimates 1990–2014” data requested from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER online database, which draws from US Census data.20

The dynamics for substantiated investigations were generally similar to those found for all investigations, with some exceptions. For example, Native Americans had a slightly higher rate of substantiated investigations compared with Whites, whereas they had a slightly lower rate of all investigations compared with Whites.

Girls had a slightly higher lifetime prevalence of maltreatment investigations at 37.6% (99.9% CI = 37.5%, 37.7%) compared with boys at 36.5% (99.9% CI = 36.4%, 36.6%). Among specific maltreatment types, girls had higher lifetime prevalence for neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse, but lifetime prevalence of physical abuse was higher for boys.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first effort to estimate lifetime risk of maltreatment investigations and the first to provide NCANDS-based lifetime maltreatment rates parsed by type of maltreatment. Our estimates reveal that, before their 18th birthday, more than one third of all US children (37.4%) are the subjects of investigated child maltreatment reports, and more than half of Black children (53.0%) are the subject of such investigations. Our cumulative rate for experiencing a maltreatment investigation is therefore 3 times the rate previously established for substantiated investigations.12 Our investigation-based estimates (as compared with previous substantiated investigation-based estimates) are far closer to estimates based on retrospective data from nationally representative samples, which are generally in the 30% to 40% range, as discussed previously.

We would suggest that our estimate may be a useful adjunct to the previous estimate, which considered only substantiated events, for several reasons. Our data close the gap between self-report data and administrative estimates, which are limited in timeframe or restricted to substantiated events. From an epidemiological perspective, and as previously discussed, current research indicates that including only substantiated cases does little to improve specificity,13,14 whereas omitting unsubstantiated investigations clearly carries a high price relative to sensitivity.

Another finding that may strike readers as remarkable is that African Americans are almost twice as likely to be investigated as Whites. This is in no way a new finding, being virtually identical to estimates from the National Incidence Studies, the annual Department of Health and Human Services national reports, and the work of Wildeman et al.9,10,12 This level of overrepresentation for Black children within CPS is consistent with their overrepresentation relative to other negative outcomes (e.g., infant mortality) and is likely mainly attributable to their economically disadvantaged position in our society23 and the powerful relationship between poverty and maltreatment.9,24

Strengths and Limitations

This study draws upon the most recently available data. It is only because of the recent accrual of yearly entries in the NCANDS Child File (2003–2014) that this study became possible. The 12 years of merged data allowed better estimates of true first-time official investigated reports without being limited to substantiated cases. The present study is also able to add to previous work by breaking out prevalence by maltreatment type.

There are several limitations to our data and methods. Our data represent only 91% of the US population. This, along with small history effects, may account for the small differences in estimated substantiation rates between our work and that of Wildeman et al. We share the limitation with Wildeman et al. of being unable to track children who move across state lines because of the way the states create identifiers,12 resulting in potential double-counting. Because the most disadvantaged populations tend to make more moves but shorter moves than more advantaged populations,25 we see this as a relatively minor limitation.

Although the period life table method is a great strength enabling this study to estimate cumulative risks without an actual long-term following-up of a real birth cohort, the method is also a limitation because its estimates are inherently approximate. The relatively stable annual investigation rates with only minor fluctuations over a decade, however, suggest that our estimates may be comparable to those from a life table based on a real birth cohort. Although we expanded the consideration of maltreatment to unsubstantiated cases, we still excluded screened-out (i.e., not investigated) cases. This is attributable both to the lack of availability of data for these cases and the scant literature characterizing such cases. Any estimate of cumulative lifetime reporting will include some “false” cases reported because of error or, very rarely, as intentional harassment.10 This does not mitigate the established predictive value of child maltreatment reports (substantiated or not) relative to a range of future negative outcomes. We also cannot capture maltreatment that was not reported. However, this problem is reduced as study time frame lengthens.

We suggest caution in interpreting the data presented for Native Americans for 2 reasons. Inconsistencies in Native American racial self-identification in Census data26 cast doubt upon the validity of a Census-based population estimate serving as the denominator in any estimate of investigation rates for this population. A second issue relates to how well tribal child protection agencies cross-report to state agencies. Fox estimated that only about 42% to 61% of child abuse cases among American Indian/Alaska Native children reach federal reporting systems (i.e., NCANDS).27 Lifetime estimates based on small self-report studies exist, but vary widely by tribal location and gender. We therefore consider our present estimate for Native Americans to be both suspect and, most likely, a substantial undercount.

Conclusions

This article provides the first available estimate, to our knowledge, of the lifetime prevalence for maltreatment investigations and investigations by subtype of maltreatment in the United States. Given the increased scientific use of maltreatment investigations, rather than only substantiated investigations, this study provides a useful reference for researchers using official records as a proxy for maltreatment as an outcome measure. Our work will also, hopefully, call attention to the rarely quoted higher lifetime cost estimates based on including unsubstantiated cases in the frequently cited CDC cost study.8

Our findings reinforce findings from retrospective studies suggesting that, over the life course, it is relatively common to have someone report a concern for abuse or neglect. As aforementioned, the body of existing research linking officially reported maltreatment to adverse outcomes adds credence to this estimate. If a report for child maltreatment could be used as a warning sign of and trigger for preventative or ameliorative intervention, later adverse consequences might be averted. Pediatricians have nearly universal access to children and constitute a front line of the effort for early identification, but many studies show that the average pediatrician is not confident in his or her ability to respond to child maltreatment.28 The increasing attention paid to child maltreatment in the medical community is welcome, as evidenced by the recent creation of the child abuse pediatrics specialty as well as models for improving pediatric care response.29 It is important that medical school education views child maltreatment as a common public health threat that deserves the same coverage in training programs as childhood obesity or immunizations. Educational professionals represent another front line as children grow older, and it is similarly important that they be able to recognize and report child maltreatment when they encounter it.

In terms of preventive interventions, there are several promising approaches that have been found to improve family functioning and may have promise for reducing maltreatment.30,31 More research is needed to demonstrate definitively that these interventions will reduce rates of maltreatment across various populations and to a meaningful degree. These findings also support the idea of universal child maltreatment prevention programming as an attractive concept. We hope the present research, which highlights the breadth of the problem, can serve as a spur to increased research, program, and policy efforts in the area of child maltreatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The data were originally collected under the auspices of the Children’s Bureau. Funding was provided by the Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services.

The analyses presented in this publication were based on data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System Child Files. These data were provided by the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect at Cornell University, and have been used with permission.

Note. The collector of the original data, the funding agency, the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, Cornell University, and the agents or employees of these institutions bear no responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here. The information and opinions expressed reflect solely the opinions of the authors.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study used only de-identified data. The Washington University Human Research Protection Office reviewed this project and determined that it does not involve activities that are subject to institutional review board oversight.

Footnotes

See also Galea and Vaughan, p. 203.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCrory E, De Brito SA, Viding E. The impact of childhood maltreatment: a review of neurobiological and genetic factors. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: a convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(3):174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(8):824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, Kim J, Porterfield S, Han L. A prospective analysis of the relationship between reported child maltreatment and special education eligibility among poor children. Child Maltreat. 2004;9(4):382–394. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currie J, Tekin E. Understanding the cycle: childhood maltreatment and future crime. J Hum Resour. 2012;47(2):509–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jonson-Reid M, Chance T, Drake B. Risk of death among children reported for nonfatal maltreatment. Child Maltreat. 2007;12(1):86–95. doi: 10.1177/1077559506296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Putnam-Hornstein E. Report of maltreatment as a risk factor for injury death: a prospective birth cohort study. Child Maltreat. 2011;16(3):163–174. doi: 10.1177/1077559511411179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(2):156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M . Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4): Report to Congress. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services. Child maltreatment 2014. 2016. Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment. Accessed March 1, 2016.

- 11.Sabol W, Coulton C, Polousky E. Measuring child maltreatment risk in communities: a life table approach. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(9):967–983. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, Putnam-Hornstein E, Waldfogel J, Lee H. The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake B. Unraveling “unsubstantiated.”. Child Maltreat. 1996;1(3):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B. Time to leave substantiation behind: findings from a national probability study. Child Maltreat. 2009;14(1):17–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ et al. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: distinction without a difference? Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(5):479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaffee SR, Maikovich-Fong AK. Effects of chronic maltreatment and maltreatment timing on children’s behavior and cognitive abilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(2):184–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(8):746–754. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect. National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Child File), FFY 2003–2014. 2016. Available at: http://www.ndacan.acf.hhs.gov/datasets/dataset-details.cfm?ID=195. Accessed February 1, 2016.

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. CDC WONDER online databse. Bridged-race population estimates 1990–2014 request. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-v2014.html. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- 21.Preston SH, Heuveline P, Guillot M. Demography: Measuring and Modeling Population Processes. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwood M. A Report on the Natural Duration of Cancer: Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects, No. 33. London, England: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drake B, Jolley J, Lanier P, Fluke J, Barth R, Jonson-Reid M. Racial bias in child protection? A comparison of competing explanations using national data. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):471–478. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelton L. The continuing role of material factors in child maltreatment and placement. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;41:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coulton CJ, Theodos B, Turner MA. Residential mobility and neighborhood change: real neighborhoods under the microscope. Cityscape A J Policy Dev Res. 2012;14(3):55–90. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doyle JM, Kao G. Are racial identities of multiracials stable? Changing self-identification among single and multiple race individuals. Soc Psychol Q. 2007;70(4):405–423. doi: 10.1177/019027250707000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox KA. Collecting data on the abuse and neglect of American Indian children. Child Welfare. 2003;82(6):707–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane WG, Dubowitz H. Primary care pediatricians’ experience, comfort and competence in the evaluation and management of child maltreatment: do we need child abuse experts? Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(2):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubowitz H, Lane WG, Semiatin JN, Magder LS. The SEEK model of pediatric primary care: can child maltreatment be prevented in a low-risk population? Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(4):259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peacock S, Konrad S, Watson E, Nickel D, Muhajarine N. Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prinz R, Sanders M, Shapiro C, Whitaker D, Lutzker J. Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: the US Triple P System Population Trial [erratum Prev Sci. 2015;16(1):168] Prev Sci. 2009;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0538-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]