Abstract

Objectives. To examine the association between exposure to breastfeeding television spots and exclusive breastfeeding (EBF).

Methods. We performed face-to-face interviews with 11 722 mothers of infants younger than 6 months using 5 cross-sectional surveys 6 or more months apart between 2011 and 2014 in Vietnam. Sample sizes were 2065 to 2593, and approximately 50% of participants lived in areas with (Alive & Thrive [A&T]-intensive [I]) and approximately 50% without (A&T-nonintensive [NI]) facilities offering counseling services. We analyzed data at individual and commune levels separately for A&T-I and A&T-NI areas.

Results. Exposure to television spots was associated with higher EBF in A&T-I (odds ratio [OR] = 3.33; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.70, 4.12) and A&T-NI (OR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.03, 1.67) areas. In A&T-I areas, mothers who could recall at least 1 message were more likely to report EBF. In A&T-NI areas, only recall of at least 3 messages was associated with higher EBF. In communes, 1 message recalled (mean score range = 0.3–2.4) corresponded to 17 (P = .005) and 8 (P = .1) percentage points higher EBF prevalence in A&T-I and A&T-NI communes, respectively.

Conclusions. Mass media should be part of comprehensive programs to promote EBF.

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) of children younger than 6 months prevents child deaths and contributes to achieving optimal growth, cognitive development, and health.1–5 Despite global efforts in recent decades, the prevalence of EBF remains suboptimal: 38% globally, 30% in the East Asia and Pacific region, and 17% in Vietnam in 2011.6,7 In Vietnam, the national EBF prevalence remained stagnant between 1997 and 2011.6,8

Social and behavior change communication can have large-scale impacts on behaviors related to child survival9 and optimal nutritional status.3,9–12 A 2014 review identified 45 peer-reviewed studies that used social and behavior change communication to address EBF, 33 of which showed statistically significant results.11 The most frequently used approach was interpersonal communication alone; some had mass media components.11 The advantages of using mass media include its reach and frequency, control over message content and delivery, consistency, and relatively low cost per person exposed.13 Mass media is viewed as especially important for promoting EBF to counter the overwhelming advertising and promotion of infant formula through a variety of channels, including mass media.14 The infant formula industry was among Vietnam’s top 5 advertisers in 2009; it spent more than US $10 million that year on advertising.15

We examined the associations between exposure to the television spots and the key outcomes—EBF, behavioral beliefs, perceived social norms, self-efficacy, and knowledge related to breastfeeding—and studied whether the associations are different in districts with versus without branded interpersonal counseling services. We also estimated the costs per woman exposed to the television spots.

METHODS

Alive & Thrive (A&T) is an international initiative whose goal is to scale up nutrition to save lives, prevent illness, and ensure healthy growth and development through the first 1000 days of life, with a focus on maternal nutrition, exclusive breastfeeding, and complementary feeding.16 The 4 components of A&T are (1) advocacy, (2) interpersonal communication and community mobilization, (3) mass communication, and (4) strategic use of data.16,17 In Vietnam, A&T aimed to increase EBF by implementing a comprehensive behavior change program, which included interpersonal counseling through branded social franchise services and a nationwide mass media campaign (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

The government health facilities in Vietnam are set up within the administrative structure of 63 cities or provinces, 644 districts, and 11 161 communes.18 A&T Vietnam supported the creation and implementation of almost 800 social franchises in existing government health facilities, most at the commune level, in 15 provinces in Vietnam. Each franchise offered a branded, brightly painted, welcoming, child-friendly space dedicated to counseling on infant and young child feeding. Trained health staff of the social franchises provided clients with 8 standardized sessions relating to EBF: 3 during the third trimester of pregnancy, 1 at the time of delivery, and 3 during the first 4 months of infancy.19

The A&T mass communication in Vietnam included (1) 4 television spots, (2) print materials (posters, booklets, leaflets, and newspaper articles), (3) out-of-home advertising (on billboards, screens in supermarkets and hospitals, bus advertisements, and loudspeakers), and (4) digital materials and communication (Web site, online forum, online counseling, a Facebook fan page, television spots online, and a mobile telephone application; Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Of the 4 television spots, 2 addressed EBF: one by focusing on the behavior of not giving water and the other by encouraging mothers to nurse more to produce more breastmilk. Our focus was on the 2 breastfeeding television spots. The television spots, developed through extensive formative research, concept testing, and pretesting and professionally produced,20,21 were broadcast in intensive bursts from December 2011 through January 2015 on national and provincial television channels.

In communes without a social franchise, referred to as A&T nonintensive (A&T-NI) areas, it was thought that mothers would benefit mostly from the television campaign. In communes where the social franchises operated, referred to as A&T-intensive (A&T-I) areas, it was thought that mothers would benefit from interpersonal counseling services; the broadcast television campaign and other mass media, such as billboards, posters, and other print materials; information broadcast through village loudspeakers; and screening the television spots at the social franchises. In both A&T-NI and A&T-I areas, women are eligible for standard antenatal checkups and benefit from national nutrition strategies and interventions, strengthened marketing regulations of breast milk substitutes, and expanded paid maternity leave (Table A).

Participants

We collected data during 5 repeated cross-sectional surveys in a 3-year time span across 4 provinces of Vietnam (Hai Phong, Quang Nam, Dak Lak, and Tien Giang), separately in A&T-I and comparable A&T-NI communes. At baseline, using systematic sampling, we recruited mothers using 3-stage cluster sampling that selected (1) intervention and comparison districts, (2) primary sampling units on the basis of a population proportionate to size method (equivalent to an average-sized village), and (3) mother–infant dyads.22,23 In the following 4 rounds, we used a similar sampling strategy with an attempt to revisit the same communes. As a result, we surveyed 118 communes in all 5 waves.

We replaced mothers who were not at home (< 5%) with preselected alternatives. The response rate was approximately 98% for the final sample sizes of 2353 in August 2011, 2065 in October 2012, 2321 in April 2013, 2593 in October 2013, and 2390 in April 2014. In each round, approximately 50% of participants were from A&T-I and the other 50% from A&T-NI. The sample size for each monthly age cohort of infants was about one sixth of the total sample.

We administered a structured questionnaire through face-to-face interviews with mothers of infants younger than 6 months. Because the surveys were 6 months apart, and Vietnamese women have average fertility of 2 children and average birth spacing of between 3 and 5 years,24 we assumed that we interviewed a negligible number of women more than once.

Variables

The main outcome was EBF, defined as the percentage of infants younger than 6 months fed only breastmilk, meaning no other foods, water, or liquids (except medications) in the 24 hours before the survey.25,26 We also examined a no-water outcome—the percentage of infants younger than 6 months who were not given water the previous day—because it was a small doable action promoted by one of the television spots.

The secondary outcomes were 4 behavioral determinants: EBF knowledge, behavioral beliefs, perceived social norms, and self-efficacy. We developed the questions used to measure these behavioral determinants on the basis of the theory of change and adjusted after cognitive testing (Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We generated a knowledge score by summing the number of correct responses across 6 knowledge questions about breastfeeding. We measured other behavioral determinants on a 6-point Likert scale by asking mothers the extent to which they disagreed or agreed with statements about EBF. We constructed the scales for behavioral beliefs (8 items), social norms (2 items), and self-efficacy (3 items) by averaging responses to all items for each category. The Cronbach alpha for each of the scales was between 0.925 and 0.933, meaning that the behavioral determinant scales were internally consistent.

The 2 measures of exposure were (1) reported exposure to either of the 2 breastfeeding television spots, and (2) the number of messages recalled. We created a recall score, ranging from 0 to 6, on the basis of the number of distinct messages mothers recalled from the television spots. We collapsed these further into 3 categories: unexposed or did not recall any message, recalled 1 to 2 messages, and recalled 3 or more messages.

Covariates included maternal characteristics such as age, ethnicity, education, and occupation. We asked mothers about the location and mode of delivery, whether they received breastfeeding advice or support from a health worker during their pregnancy and in the 3 days after birth, and whether they received counseling at social franchises. Infant-level variables included gender and age at the time of interview.

Statistical Analysis

We performed analyses separately for A&T-I and A&T-NI areas using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). With the exception of the commune-level analysis, we used complex survey commands to account for clustering.

First, to examine the trends of EBF and one of its component behaviors—no water—we compared the prevalence at each follow-up round with that at baseline. Within each round, we compared the prevalence of EBF by exposure to the breastfeeding television spots (e.g., recalled 1–2 or ≥ 3 messages vs unexposed or did not recall). We also compared the mean for each behavioral determinant with those at baseline and by exposure level. We used nonoverlapping 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to define the difference of proportions or means.

Second, to control for potential confounding factors, we used multiple logistic regression models to examine the association between EBF prevalence and our 2 measures of exposure—any exposure to television spots and the number of messages recalled. We used multiple linear regression models to estimate the associations between the exposure variables and each of the behavioral determinant scales. We pooled data from rounds 2 through 5 because the association between exposure and outcome variables was similar across rounds. All models controlled for birth history; breastfeeding advice or support received during pregnancy or at the time of birth; maternal age, education, ethnicity, and occupation; and infant’s age and gender. Models for A&T-I areas also controlled for receiving counseling at social franchises.

Third, to strengthen the plausibility that observed associations resulted from neither reverse causality nor changes in unmeasured confounders, we conducted a geographic longitudinal analysis. We collapsed EBF prevalence and messages recalled by commune and round. Then we used a bootstrapping (with 10 000 replications) linear regression model at the commune level to regress EBF prevalence in rounds 2 through 5 on exposure to television spots, adjusted for EBF prevalence at baseline.

Fourth, we estimated the adjusted population attribution fraction on the basis of the cross-sectional association between exposure and EBF in A&T-NI areas, with a hypothetical scenario that all mothers with infants younger than 6 months were exposed to the breastfeeding television spots and recalled at least 1 message.

Finally, to arrive at the cost per woman reached, we estimated (1) the number of women aged 15 to 35 years on the basis of Vietnam population structure,18 (2) the number of women exposed to the breastfeeding television spots on the basis of the prevalence obtained from surveys conducted in rounds 2 through 5 in A&T-NI areas, and (3) the cost per woman reached by dividing the total expenditure for the 2 television spots from the costing study27 by the number of women reached. Similarly, we estimated the number of infants younger than 6 months in Vietnam and estimated the cost per woman with an infant younger than 6 months reached.

RESULTS

In general, mothers and infants at baseline and subsequent rounds in both A&T-NI and A&T-I areas had similar characteristics: mean age of infants was 3.3 months; the mean age of mothers was approximately 28 years; approximately 90% of mothers belonged to the majority ethnicity (Kinh); and approximately 40% had some high school education (Table 1). Cesarean deliveries were more prevalent in rounds 2 through 5 than at baseline in both areas (nonoverlapping 95% CI). In A&T-NI areas, the prevalence of mothers who received breastfeeding support at birth was higher in rounds 2 through 5 than at baseline (40% vs 33%; nonoverlapping 95% CI). In A&T-I areas, more mothers received breastfeeding advice during pregnancy and breastfeeding support at birth in rounds 2 through 5 than at baseline, and 25% of mothers received franchise counseling services. In addition, mothers in A&T-I areas reported greater exposure to the breastfeeding television spots and recalled more messages than did those who lived in A&T-NI areas (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Key Maternal and Infant Characteristics and Exposure to Breastfeeding Television Spots by Intervention Area: Vietnam, 2011–2014

| A&T-NI Area, % or Mean (95% CI) |

A&T-I Area, % or Mean (95% CI) |

|||

| Characteristic | Round 1, Baseline (n = 1170) | Rounds 2–5 (n = 4648) | Round 1, Baseline (n = 1183) | Rounds 2–5 (n = 4721) |

| Mother | ||||

| Age, y | 27.3 (26.9, 27.7) | 27.7 (27.5, 27.9) | 27.3 (26.9, 27.7) | 27.9 (27.6, 28.2) |

| Of majority Kinh ethnicity | 88.4 (82.3, 92.6) | 88.8 (84.0, 92.3) | 90.5 (84.8, 94.3) | 90.8 (87.1, 93.5) |

| Has ≥ 9 y of education | 37.8 (34.1, 41.6) | 43.1 (40.6, 45.6) | 39.1 (35.7, 42.6) | 45.0a (42.7, 47.2) |

| Is a farmer | 40.7 (37.0, 44.5) | 26.8a (23.5, 30.3) | 39.3 (34.8, 44.0) | 28.8a (25.4, 32.4) |

| Delivery modes | ||||

| Vaginal births outside hospitals | 14.7 (12.1, 17.8) | 8.7a (6.8, 10.9) | 20.5 (15.5, 26.8) | 12.0a (9.3, 15.3) |

| Vaginal births in hospitals | 62.7 (59.5, 65.7) | 62.7 (60.5, 64.8) | 60.3 (54.8, 65.5) | 63.6 (60.5, 66.6) |

| Cesarean deliveries in hospitals | 22.7 (20.5, 25.0) | 28.7a (26.8, 30.5) | 19.2 (16.9, 21.8) | 24.4a,b (22.8, 26.1) |

| Infant | ||||

| Is a boy | 53.1 (50.4, 55.7) | 52.1 (50.6, 53.6) | 51.8 (48.7, 55.0) | 53.1 (51.7, 54.4) |

| Age, mo | 3.3 (3.2, 3.4) | 3.3 (3.2, 3.3) | 3.3 (3.2, 3.4) | 3.4 (3.3, 3.4) |

| Breastfeeding counseling and support | ||||

| Advice during pregnancy | 48.8 (45.2, 52.4) | 48.7 (46.4, 50.9) | 47.7 (44.1, 51.3) | 66.2a,b (63.6, 68.7) |

| Support in the first 3 d after birth | 33.0 (30.2, 35.9) | 39.8a (37.4, 42.2) | 36.6 (33.6, 39.7) | 50.4a,b (47.3, 53.5) |

| Advice and support at social franchises | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 24.7b (21.3, 28.5) | ||

| Exposed to the television spots | 72.4 (70.2, 74.6) | 79.1b (77.4, 80.7) | ||

| Recall of exposure to the television messages, no. | ||||

| 0 or unexposed | 42.2 (39.8, 44.5) | 31.2b (29.4, 33.1) | ||

| 1–2 | 35.4 (33.6, 37.2) | 37.3 (35.9, 38.8) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 22.5 (20.7, 24.4) | 31.5b (29.7, 33.4) | ||

Note. A&T-I = Alive & Thrive-intensive; A&T-NI = Alive & Thrive-nonintensive; CI = confidence interval.

Nonoverlapping 95% CI compared with baseline.

Nonoverlapping 95% CI compared with corresponding rounds of A&T-NI area.

Exclusive Breast Feeding in Alive & Thrive-Nonintensive Areas

In A&T-NI areas, the EBF prevalence after the launch of the television campaign (i.e., pooled across rounds 2–5) of 36% was similar to that at baseline (32%; overlapping 95% CI; Table D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Compared with baseline, exposure to the television spots in rounds 2 through 5 (using pooled data) was associated with higher prevalence of EBF (model 1: odds ratio [OR] = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.03, 1.67; Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Adjusted Associations Between Exposure to Breastfeeding Television Spots and Study Outcomes by Intervention Area: Vietnam, 2011–2014

| A&T-NI Area (n = 5818) |

A&T-I Area (n = 5904) |

|||||||||

| Model | Exclusive Breastfeeding, OR (95% CI) | Knowledge, b (95% CI) | Behavioral Beliefs, b (95% CI) | Social Norms, b (95% CI) | Self-Efficacy, b (95% CI) | Exclusive Breastfeeding, OR (95% CI) | Knowledge, b (95% CI) | Behavioral Beliefs, b (95% CI) | Social Norms, b (95% CI) | Self-Efficacy, b (95% CI) |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||

| Baseline (Ref) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unexposed | 0.90 (0.69, 1.18) | 0.12 (–0.10, 0.35) | 0.21 (0.04, 0.39) | 0.21 (0.02, 0.39) | 0.22 (0.08, 0.36) | 2.66 (2.02, 3.51) | 0.74 (0.61, 0.87) | 0.70 (0.60, 0.79) | 0.93 (0.75, 1.11) | 0.50 (0.40, 0.60) |

| Exposed | 1.31 (1.03, 1.67) | 0.47 (0.28, 0.67) | 0.42 (0.28, 0.56) | 0.55 (0.38, 0.71) | 0.34 (0.24, 0.45) | 3.33 (2.70, 4.12) | 0.99 (0.88, 1.09) | 0.89 (0.79, 0.98) | 1.15 (1.00, 1.31) | 0.67 (0.58, 0.76) |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||

| Baseline (Ref) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unexposed or did not recall | 0.89 (0.70, 1.15) | 0.09 (–0.13, 0.31) | 0.18 (0.01, 0.34) | 0.19 (0.02, 0.36) | 0.19 (0.07, 0.32) | 2.42 (1.86, 3.14) | 0.71 (0.59, 0.84) | 0.65 (0.56, 0.75) | 0.89 (0.71, 1.07) | 0.49 (0.40, 0.59) |

| Recalled 1–2 messages | 1.20 (0.92, 1.56) | 0.42 (0.22, 0.62) | 0.35 (0.20, 0.49) | 0.48 (0.30, 0.65) | 0.30 (0.19, 0.41) | 3.14 (2.48, 3.98) | 0.91 (0.80, 1.03) | 0.83 (0.73, 0.93) | 1.09 (0.92, 1.25) | 0.64 (0.54, 0.73) |

| Recalled ≥ 3 messages | 1.95 (1.50, 2.55) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.05) | 0.76 (0.62, 0.90) | 0.92 (0.74, 1.10) | 0.55 (0.43, 0.66) | 4.69 (3.76, 5.84) | 1.25 (1.14, 1.36) | 1.13 (1.03, 1.22) | 1.41 (1.26, 1.56) | 0.81 (0.72, 0.90) |

Note. A&T-I = Alive & Thrive-intensive; A&T-NI = Alive & Thrive-nonintensive; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Models controlled for birth history (cesarean delivery and delivery in hospital, breastfeeding advice or support during pregnancy and at birth), maternal characteristics (age, completion of ≥ 9 y education, being of Kinh ethnicity, and being a farmer), and infant characteristics (age and gender). In A&T-I areas, the model also adjusted for receipt of counseling services at social franchises. We defined exclusive breastfeeding as feeding breastmilk exclusively in the previous 24 h (i.e., no foods or liquids except medications such as drops and syrups).

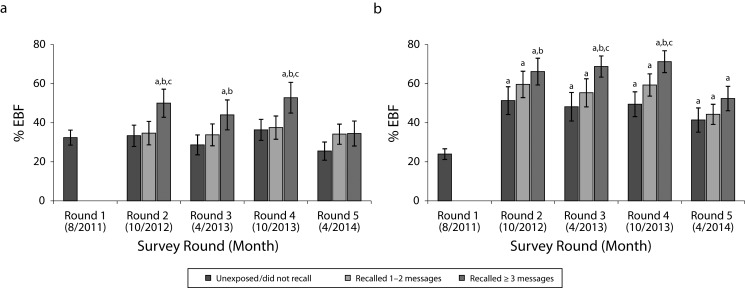

Mothers who recalled 3 or more messages reported higher EBF prevalence than did those who were unexposed or did not recall any message in rounds 2 through 4 (nonoverlapping 95% CI; Figure 1). Logistic regression models controlling for covariates showed consistent findings (OR = 1.95; 95% CI = 1.50, 2.55; Table 2). We observed similar results for the association between the exposure to the television spots and withholding water (Table D). On the basis of the population-attributable fraction from model 2 (Table 2), if all mothers with infants younger than 6 months were exposed to the breastfeeding television spots and recalled at least 1 message, the EBF prevalence would be 13.5% points higher.

FIGURE 1—

Prevalence and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) of Exclusive Breastfeeding (EBF) of Children Younger Than 6 Months in Alive & Thrive by Exposure Level to Breastfeeding Television Spots in (a) Nonintensive Areas and (b) Intensive Areas: Vietnam, 2011–2014

Note. We defined exclusive breastfeeding as feeding breastmilk exclusively in the previous 24 h (i.e., no foods or liquids with the exception of medications such as drops and syrups).

aNonoverlapping 95% CI compared with baseline.

bNonoverlapping 95% CI compared with unexposed or did not recall.

cNonoverlapping 95% CI compared with recalled 1–2 messages.

Exclusive Breast Feeding in Alive & Thrive-Intensive Areas

In A&T-I areas, the EBF prevalence, pooled across rounds 2 through 5 (56%), was higher than baseline (24%; nonoverlapping 95% CI; Table D). Compared with baseline, EBF prevalence was statistically higher at each follow-up round. Furthermore, at each follow-up round, mothers who recalled 3 or more messages reported significantly higher EBF prevalence than did those who were unexposed or did not recall any messages (Figure 1).

Logistic regression models controlling for covariates supported this association (Table 2). We found similar trends in the association between the exposure to the television spots and withholding water (Table D).

Television Spots and Exclusive Breast Feeding Determinants

The scores of knowledge, behavioral beliefs, social norms, and self-efficacy scales were statistically higher in rounds 2 through 5 than at baseline in both areas (Table E, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

In each round, the scores were higher for mothers who could recall 3 or more messages than for those who were unexposed or did not recall any messages (nonoverlapping 95% CI; Table E). Consistently, in multiple linear regression models compared with baseline, exposure to the television spots was associated with higher scores of knowledge, behavioral beliefs, social norms, and self-efficacy (Table 2).

Television Spots and Exclusive Breast Feeding at Commune Level

In the longitudinal analysis at the commune level, a difference of 1 message recalled (mean score range = 0.3–2.4) corresponded to 8 (P = .1) and 17 (P = .005) percentage points higher prevalence of EBF in A&T-NI and A&T-I communes, respectively (Table 3).

TABLE 3—

Longitudinal Association Between Exposure to Breastfeeding Television Spots and Exclusive Breastfeeding Practice at Commune Level by Intervention Area: Vietnam, 2011–2014

| A&T-NI Communes (n = 61), b (95% CI) |

A&T-I Communes (n = 57), b (95% CI) |

|||

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| Constant | 13.3 (4.1, 22.5) | 20.4 (14.8, 26.0) | 17.2 (–3.6, 38.0) | 41.1 (33.3, 48.9) |

| Baseline EBF prevalence | 0.349 (0.135, 0.563) | 0.344 (0.132, 0.555) | 0.493 (0.249, 0.737) | 0.510 (0.269, 0.752) |

| Messages recalled, no. | 7.97 (–1.49, 17.40) | 16.70 (5.01, 28.50) | ||

| Message recalled, tercile | ||||

| 2nd | 2.49 (–4.40, 9.39) | −0.71 (–11.20, 9.80) | ||

| 3rd (highest) | 8.65 (–0.12, 17.40) | 13.50 (4.00, 23.00) | ||

Note. A&T-I = Alive & Thrive-intensive; A&T-NI = Alive & Thrive-nonintensive; CI = confidence interval; EBF = exclusive breastfeeding. Bootstrapping (with 10 000 replications) linear regression models at the commune level regressed EBF prevalence in rounds 2–5 on exposure to the television spots, adjusted for EBF prevalence at baseline. We defined EBF as feeding breastmilk exclusively in the previous 24 h (i.e., no foods or liquids except medications such as drops or syrups).

In the parallel analysis using terciles of messages recalled, communes in the highest recall tercile (compared with the lowest) had 9 (P = .05) and 14 (P = .005) percentage points higher prevalence of EBF in A&T-NI and A&T-I communes, respectively (Table 3).

Cost per Woman Exposed to Television Campaign

On the basis of the population structure, we estimated that there were 16 148 057 women aged 15 to 35 years in Vietnam between 2011 and 2014,18 and 9 349 725 women had seen the breastfeeding television spots, because 58% of mothers in A&T-NI areas could recall 1 or more message. From a separate costing study, we estimated the total expenditure for the mass media campaign—including the cost of development, design, and testing; production of the 2 television spots; and the purchase of airtime on national and provincial stations—at US $1 258 529.27 Consequently, the cost per woman of reproductive age reached was US $0.13.

During the 3.5-year period, we estimated that Vietnam had a total of 4 998 000 infants younger than 6 months on the basis of the 2012 annual births and neonatal mortality rate.7 Among them, an estimated 2 893 842 infants younger than 6 months had mothers exposed to the television spots (applying the reach of 58%). The estimated cost per woman with an infant younger than 6 months reached was US $0.43.

DISCUSSION

In both nonintensive and intensive areas, mothers’ exposure to breastfeeding television spots and message recall was associated with higher EBF. This association was paralleled by an association between exposure and message recall and the behavioral determinants of EBF as well as withholding water from babies younger than 6 months. The longitudinal commune-level analysis provides evidence for the hypothesized causal order from exposure to changes in behavioral determinants and EBF behaviors. The upward trend in EBF prevalence and mean scores of behavioral determinants that dropped in round 5 may be explained by a decreased budget for airing and increased fatigue with the 3-year-old television spots.

Our results show a stronger association between the television spots and EBF behavior in areas with additional interventions than in those with television spots alone, which is consistent with previous studies. For example, in Jordan, the combination of mass media with training for health providers and changes in delivery practices in health facilities, such as rooming-in and decreased use of prelacteals, increased prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding.28 In Armenia, mass media and community-based peer health educators improved EBF prevalence.29 Conversely, a multichannel mass media campaign without interpersonal counseling provided marginal effects on EBF in Uganda,30 Brazil,31 and Burkina Faso.32

Because of the television spots’ theory-based design, high production values, and broadcast frequency similar to that of commercial television campaigns, one might expect that the associations between exposure to the television spots and EBF would be comparable in both areas. Instead, there was a stronger association between mass media and EBF in A&T-I areas than in A&T-NI areas, which had television spots only. We posit numerous possible explanations for the differences between nonintensive and intensive areas.

First, in A&T-NI areas, the only mass media activity was broadcasting the television spots on national and provincial stations. In A&T-I areas, the mass media campaign itself was more intensive than in A&T-NI areas because campaign messages were also echoed via television spots on screens at franchises, take-home materials (e.g., leaflets and booklets), posters, billboards, and short dramas about infant feeding broadcast on village loudspeakers. Women who had visited a franchise were more likely to remember exposure and to recall messages. It is also possible that the mass media campaign motivated women to visit franchises.

Second, exposure to the television spots and message recall were associated with shifting knowledge, behavioral beliefs, social norms, and self-efficacy in both A&T-NI and A&T-I areas. The translation from improved behavioral determinants into EBF behavior may have been potentiated by additional support, such as interpersonal counseling services in A&T-I areas.

Finally, the media campaign may have enhanced the effects of the franchise counseling in 4 ways. First, the television spots may have improved counselors’ motivation or performance. Second, the highly emotional tone of the television spots may have added a new dimension to the content of messages that were also delivered through interpersonal counseling. Third, mothers may have been more persuaded to adopt a behavior when exposed to messages through more than 1 channel. Fourth, the television spots may have helped to shift social norms related to EBF, meaning that mothers perceived that others like them or others who influence them support EBF.

Limitations and Strengths

This study has several limitations. In Vietnam, access to television is high and the national channels on which the television spots were aired to maximize reach were seen all over the country, making it difficult to identify a control group that would not have been exposed to the campaign. This is a common limitation in evaluations of nationwide mass media campaigns. Reverse causation associated with cross-sectional design might be an issue. For example, those who engage in EBF and have more positive EBF behavioral beliefs, perceived social norms, self-efficacy, and knowledge may better recall the television spots and campaign messages. In addition, it was difficult to determine the temporal relationship between exposure to television spots, other mass media materials, franchise use, and behavior change in A&T areas.

The study has several strengths as well. The large sample sizes and repeated measures allowed us to conduct analyses that were unprecedented in evaluations of mass media campaigns to promote EBF. This is among few studies examining the association between mass media and precursors of behaviors other than knowledge, such as beliefs, social norms, and self-efficacy. Finally, multiple analytic approaches, including the longitudinal analysis at the commune level, have allowed us to mitigate some of the weaknesses we have described.

Public Health Implications

Our study supports a growing literature showing that mass media can make a valuable contribution to behavioral beliefs, social norms, self-efficacy, and knowledge, which in turn prepares mothers to adopt exclusive breastfeeding behaviors. At US $0.13 per woman of reproductive age reached and US $0.43 per woman with an infant younger than 6 months reached, a commercial-grade television campaign was a sound investment for extending the program’s reach.

Our findings may persuade practitioners to use theory-based and emotion-focused television spots for social and behavior change, especially as part of comprehensive programs. Furthermore, our findings may aid people in fields beyond nutrition as they consider mass media for similarly complex behaviors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, through Alive & Thrive, managed by FHI 360.

A part of our findings was presented at Experimental Biology 2016; April 22–26, 2016; San Diego, CA.

We thank Robert C. Hornik, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, for guidance in the original design of this evaluation and comments and suggestions to improve the analysis and documentation of this study. We thank Nadra Franklin, FHI 360, for guidance on study design, sampling plan, and the instruments. We thank Nguyen H. Giang for overseeing creative development, pretesting, and producing the television spots; buying managed media; and contributing to campaign monitoring. We thank Pearl Ang for valuable comments and suggestions for the formative research and creative development of the television spots. We are grateful to Ann Hendrix-Jenkins and Laura Itzkowitz from Alive & Thrive as well as anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions, which helped to improve this article.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The study protocol was approved by the Institute of Social and Medical Studies institutional review board and FHI 360’s Protection of Human Subjects Committee. We obtained written informed consent from all participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haschke F, Haiden N, Detzel P, Yarnoff B, Allaire B, Haschke-Becher E. Feeding patterns during the first 2 years and health outcome. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;62(suppl 3):16–25. doi: 10.1159/000351575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Children’s Fund. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387(10017):491–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet. 2013;382(9890):452–477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60996-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Vietnam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2011. Hanoi: Vietnam; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The State of the World’s Children 2015: Reimagine the Future. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Committee for Population Family and Children. Vietnam Demographic and Health Survey 1997. Hanoi, Vietnam: Statistical Publishing House; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox E, Obregón R. Population-level behavior change to enhance child survival and development in low- and middle-income countries. J Health Commun. 2014;19(suppl 1):3–9. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.934937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabrizio CS, van Liere M, Pelto G. Identifying determinants of effective complementary feeding behaviour change interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10(4):575–592. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lamstein S, Stillman T, Koniz-Booher P, et al. Evidence of effective approaches to social and behavior change communication for preventing and reducing stunting and anemia: findings from a systematic literature review. Arlington, VA: US Agency for International Development; 2014.

- 12.Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. 2010;376(9748):1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naugle DA, Hornik RC. Systematic review of the effectiveness of mass media interventions for child survival in low- and middle-income countries. J Health Commun. 2014;19(suppl 1):190–215. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.918217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global Packaged Food: Market Opportunities for Baby Food to 2013. London, UK: Euromonitor International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stocking B. Baby-formula firms test law in Vietnam. 2009. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/09/19/AR2009091902417.html. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- 16.Alive & Thrive. Program components. 2016. Available at: http://www.aliveandthrive.org. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- 17.Baker J, Sanghvi T, Hajeebhoy N, Martin L, Lapping K. Using an evidence-based approach to design large-scale programs to improve infant and young child feeding. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34(3 suppl):S146–S155. doi: 10.1177/15648265130343S202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Statistical data: population and labor. 2014. Available at: http://www.gso.gov.vn. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- 19.Overview of the Social Franchise Model for Delivering Counseling Services on Infant and Young Child Feeding. Hanoi, Vietnam: Alive & Thrive; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alayón S, Naugle D, Jimerson A . Using Behavioral Theory to Evaluate the Impact of Mass Media on Breastfeeding Practices in Vietnam: Evaluation Plan and Baseline Findings. Washington, DC: Alive & Thrive; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanghvi T, Jimerson A, Hajeebhoy N, Zewale M, Nguyen GH. Tailoring communication strategies to improve infant and young child feeding practices in different country settings. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34(3 suppl):S169–S180. doi: 10.1177/15648265130343S204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Secondary Baseline Survey Report. Hanoi: FHI 360. Hanoi, Vietnam: Alive & Thrive; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuan NT, Nguyen PH, Hajeebhoy N, Frongillo EA. Gaps between breastfeeding awareness and practices in Vietnamese mothers result from inadequate support in health facilities and social norms. J Nutr. 2014;144(11):1811–1817. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.198226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United Nations Children’s Fund. Vietnam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2014. Hanoi, Vietnam: General Statistics Office of Vietnam; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daelmans B, Dewey K, Arimond M Working Group on Infant Young Child Feeding Indicators. New and updated indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30(2 suppl):S256–S262. doi: 10.1177/15648265090302S210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Conclusions of a Consensus Meeting Held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington DC, USA. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoang VM, Nguyen HP, Rawat R. Vietnam Alive & Thrive Costing Study: Total Expenditure, Costs and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Hanoi, Vietnam: Alive & Thrive; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDivitt JA, Zimicki S, Hornik R, Abulaban A. The impact of the Healthcom mass media campaign on timely initiation of breastfeeding in Jordan. Stud Fam Plann. 1993;24(5):295–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson ME, Harutyunyan TL. Impact of a community-based integrated management of childhood illnesses (IMCI) programme in Gegharkunik, Armenia. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(2):101–107. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta N, Katende C, Bessinger R. An evaluation of post-campaign knowledge and practices of exclusive breastfeeding in Uganda. J Health Popul Nutr. 2004;22(4):429–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rea MF. The Brazilian national breastfeeding program: a success story. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1990;31(suppl 1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(90)90082-V. discussion 83–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarrassat S, Meda N, Ouedraogo M et al. Behavior change after 20 months of a radio campaign addressing key lifesaving family behaviors for child survival: midline results from a cluster randomized trial in rural Burkina Faso. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(4):557–576. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]