Achieving universal health coverage (UHC) ranks high on the global health agenda, and its inclusion as a target under the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has ensured policymakers’ attention until 2030 and beyond. However, although it represents a historic landmark, the commitment to UHC leaves unsettled what role public health interventions will play.1 Going forward, three steps are key: to clarify how public health ought to be conceptualized relative to UHC, to improve data on public health spending, and to expand the scope of evaluations.

Both clinical services and public health interventions—understood as population-based, preventive measures—are critical to health systems and population health. However, the relationship between UHC and public health interventions in the current discussion is an uneasy one. Some prominent definitions of UHC are explicitly restricted to health care,2 and the SDG target on UHC explicitly focuses on “health-care services.” Even though some other prominent definitions of UHC do include public health interventions in the concept (http://bit.ly/1gEMiw6 and http://bit.ly/1BdUjnW)—and the first global monitoring report included improved water and sanitation—major publications share a near-exclusive emphasis on clinical services (http://bit.ly/1gEMiw6 and http://bit.ly/1BdUjnW).2 The focus on clinical services is evidenced—and supported—by the UHC vocabulary. “Access to services” and financial risk protection related to “out-of-pocket expenditures” align poorly with public health interventions, such as tobacco taxes, regulation of alcohol, informational campaigns on healthy diets, and public health capacities for epidemic preparedness and response.

With public health interventions playing such a marginal role in the current pursuit of UHC, there is a real risk that the momentum of UHC will push these interventions further into the periphery of global and national efforts to improve health. So what is the best way of ensuring parity and complementarity between UHC and public health?

POSITIONING PUBLIC HEALTH STRATEGICALLY

A key question is whether stakeholders should push for subsuming public health interventions under UHC or whether they should pursue a “parallel wheel” strategy. The first option has some obvious advantages. In particular, given UHC’s popularity, piggybacking onto UHC may increase the attention paid to public health interventions. However, in view of the common focus on a narrowly construed UHC, public health interventions are likely to remain UHC’s poor cousin.

Public health advocates may therefore prefer the opposite strategy: to stress that the concept of UHC does not fully incorporate public health interventions. From this perspective, UHC includes some preventive efforts aimed at the entire population, such as vaccinations (which indeed are part of the SDG target on UHC), but is primarily concerned with individual-level services. Even if public health lacks the professional, commercial, and patient lobbying that pushes much of the UHC agenda, we believe that this approach will be most effective at securing attention to population-level public health interventions in the long term. It is likely to also benefit the pursuit of UHC. For if UHC is used to cover everything, it will lose distinctiveness and coherence as a concept and goal. By not shoehorning all public health interventions into UHC, clarity and focus in policy and practice can be secured.

To make progress in this direction, there are multiple avenues that global institutions steering the debate and setting the agenda can explore. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank can structure their landmark reports into two parts—one on UHC and one on public health interventions—where no part is subordinate to the other. The message inherent in such a structure could be reinforced by the same reports having both UHC and public health in their titles. At the national level, governments and other key actors can pursue a similar approach.

IMPROVING DATA ON SPENDING

Whichever strategy one pursues, it is crucial to have a clear understanding of what relative priority is assigned to public health. Although data on clinical services expenditure also have limitations, they are far more developed than the corresponding data for public health interventions, partly because of challenges with definitions and coding as well as the multiplicity of actors and sectors involved.3

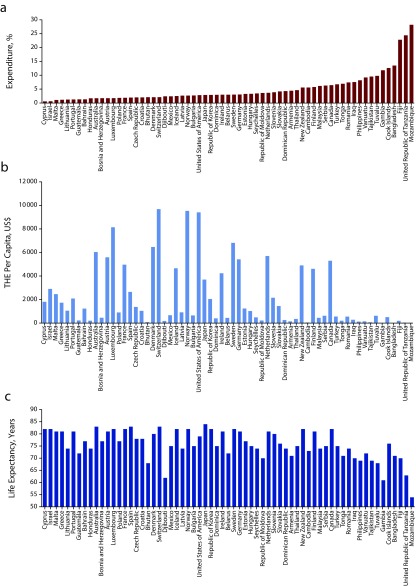

Figure 1 shows the share of total health expenditure (THE) going to prevention and public health services, THE per capita, and life expectancy at birth for every country with 2012–2014 data on that share. Three things stand out. First, only 65 of 194 WHO member states have data on the proportion of THE allocated to prevention and public health services for any year in that period. Second, the proportions vary widely. They range from around 0.6% to more than 28%, with the 14 countries with the largest shares all being low- or middle-income countries. Part of the explanation for these two points is likely to be that expenditures on public health interventions can be particularly difficult to code. The most recent System of Health Accounts seeks to address this, but it acknowledges that major challenges remain.3 Third, many of the countries with the highest proportion of THE dedicated to prevention and public health services are among the countries with the lowest THE per capita as well as the lowest life expectancy at birth. These complex relationships, however, have generally received little scrutiny—again, probably because of limited data. Taken together, this suggests that our current understanding of spending on public health interventions is severely incomplete.

FIGURE 1—

Graphic Representation of (a) the Expenditure on Prevention and Public Health and Services as a Percentage of Total Health Expenditure, (b) THE Per Capita, and (c) Life Expectancy at Birth

Note. Expenditures are given in US dollars as calculated with the official exchange rates at the time. Estimates of expenditure on prevention and public health are not fully restricted to population-based interventions. We used the most recently available data from the World Health Organization’s Global Health Expenditure Database (2012–2014). For Guatemala, we used life expectancy for 2014 from the World Bank.

Intensified efforts to ensure robust data on public health spending are therefore needed. As is well known, it is hard to make progress without measurement. Accurate data on spending on public health vis-à-vis clinical services are essential for understanding, debating, and improving the balance between the two. Moreover, reliable measurements are required for monitoring change over time and for making informative comparisons across countries.

EXPANDING THE EVALUATION OF INTERVENTIONS

Directly related to the issue of spending is a need to improve evidence on the value of public health interventions. Although several interventions of this kind have a solid evidence base,4 simply assuming that prevention is better than cure and that these interventions thus provide value for the money will only go so far. Greater use of cost-effectiveness analyses in both public health and clinical care is critical, but it is just as important to broaden evaluations beyond the narrow focus on total health outcomes. Many public health interventions provide economic or educational benefits alongside health benefits, and this can render these interventions far superior to clinical services overall. School feeding programs, for example, tend to improve energy intake and micronutrient status but also school attendance.5 Likewise, in addressing the social determinants of health and other factors, public health interventions often have a unique impact on health inequalities. Increases in tobacco prices, for example, tend to have a proequity effect on socioeconomic disparities in smoking.6 All of this shows that to get priorities and spending right, nonhealth outcomes and distributional impacts need to be systematically incorporated in the appraisal of public health interventions.

TOWARD 2030

Public health interventions are critical for ensuring healthy lives and promoting sustainable development. The three steps we set out for making public health thrive alongside UHC are relevant for all countries now charting out their course to the SDGs. Early action is likely to affect both the speed and direction toward the new global goals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schmidt H, Gostin LO, Emanuel EJ. Public health, universal health coverage, and Sustainable Development Goals: can they coexist? Lancet. 2015;386(9996):928–930. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotlear D, Nagpal S, Smith O, Tandon A, Cortez R. Going Universal: How 24 Developing Countries Are Implementing Universal Health Coverage Reforms From the Bottom Up. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Eurostat, World Health Organization. A System of Health Accounts. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation [erratum in Lancet. 2014;383(9913):218] Lancet. 2013;382(9908):1898–1955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jomaa LH, McDonnell E, Probart C. School feeding programs in developing countries: impacts on children’s health and educational outcomes. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(2):83–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill S, Amos A, Clifford D, Platt S. Impact of tobacco control interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in smoking: review of the evidence. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e89–e97. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]