Abstract

There is convincing evidence that abnormalities of regional brain function exist in Parkinson’s disease (PD). However, many resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) studies using amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF) have reported inconsistent results about regional spontaneous neuronal activity in PD. Therefore, we conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis using the Seed-based d Mapping and several complementary analyses. We searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science databases for eligible whole-brain rs-fMRI studies that measured ALFF differences between patients with PD and healthy controls published from January 1st, 2000 until June 24, 2016. Eleven studies reporting 14 comparisons, comparing 421 patients and 381 healthy controls, were included. The most consistent and replicable findings in patients with PD compared with healthy controls were identified, including the decreased ALFFs in the bilateral supplementary motor areas, left putamen, left premotor cortex, and left inferior parietal gyrus, and increased ALFFs in the right inferior parietal gyrus. The altered ALFFs in these brain regions are related to motor deficits and compensation in PD, which contribute to understanding its neurobiological underpinnings and could serve as specific regions of interest for further studies.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder associated with progressive disability and chronic suffering that lead to a great social burden1,2. PD is traditionally defined as a movement disorder resulting from a prominent loss of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway, but more recently it has been demonstrated that widespread non-motor symptoms, such as cognitive impairment and mood disorders, are also prevalent, which involve extensive brain regions3,4,5,6. PD is clinically and etiologically heterogeneous and its complex neurobiological underpinnings remain to be fully elucidated3.

During the last decade, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) has become an established approach for exploring functional neuroanatomy in vivo and numerous studies have sought to unravel the key abnormalities of brain function involved in the pathophysiology of PD7. Amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF), an index to measure changes in resting-state blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signals, has been shown to reflect regional spontaneous neuronal activity8. ALFF has been widely used to explore regional changes of brain function in neuropsychiatric disorders9,10,11,12,13,14. Aberrant ALFF patterns in PD have been shown to be related to motor subtypes15, motor severity16,17, disease progression17,18, apathy16, depression16,19,20,21, and visual hallucinations22. These studies indicate that PD pathophysiology is involved in widespread abnormalities of regional spontaneous neuronal activity beyond those within the motor network. Although ALFF studies have substantially enhanced our understanding of the neural substrates underlying PD, conclusions from these studies have not been entirely consistent, raising questions about their replicability and reliability. Widespread and heterogeneous ALFF abnormalities in many brain regions, such as the motor cortices, striatum, cerebellum, and brain stem, as well as frontal, temporal, parietal, occipital, and cingulate cortices (see Supplementary Table 1)13,15,17,18,19,22,23,24,25,26,27, were observed across studies in patients with PD in comparison with healthy controls. Differences in sample size, disease severity, disease duration, medication status, and imaging methodology may partially contribute to these inconsistencies. For example, ALFF differences about effect of therapy were observed in patients with PD23,25. Thus, to overcome the inconsistences across single ALFF studies is very timely and necessary.

We aimed at conducting a quantitative and voxel-based meta-analysis of ALFF changes in patients with PD. In addition, we set out to perform meta-regression analyses to examine the confounding effects of demographics and clinical variables on ALFF changes in PD. Furthermore, several complementary analyses of jackknife sensitivity, heterogeneity, and publication bias were performed to explore the most consistent and reliable findings. Here, we used Seed-based d Mapping (SDM), a well validated meta-analytic tool for coordinate-based neuroimaging data28,29,30,31,32,33. SDM has already been applied to identify reliable brain anatomical or functional alterations in many neuropsychiatric disorders including Alzheimer’s disease34,35, PD36, multiple sclerosis37,38, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis29,39, depression30,40, and others28,33.

Results

Included studies and sample characteristics

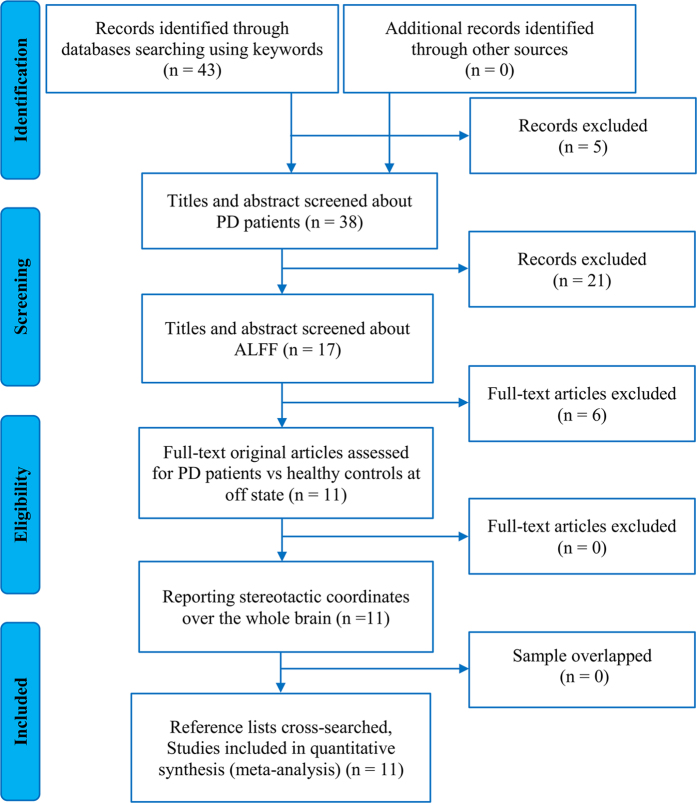

Figure 1 showed the flow diagram for inclusion/exclusion of studies in the meta-analysis. The systematic search yielded a total of 43 relevant documents. After initially screen of the titles and abstracts, 17 ALFF studies were potentially eligible for this meta-analysis. Of these, 6 studies were excluded because of the following reasons: one was an abstract41; one used a method of regions of interest42; one applied an approach of support vector machine training43; one did not perform a direct comparison between PD patients and healthy controls16; and two just reported findings from the on-state of PD patients22,44. The remaining 11 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Of these, two studies reported both on- and off-state results, only the latter datasets were included23,25. One study reported the baseline and follow-up findings, only the former dataset was included17. Two studies reported two datasets, respectively with non-depressed and depressed PD, and only the non-depressed datasets were included19,21. Another two studies reported two distinct15 and three distinct datasets18, respectively, and all of them were included. Totally, 11 original studies reporting 14 datasets were finally included in this meta-analysis13,15,17,18,19,21,23,24,25,26,27. These included datasets reported ALFF differences between 421 patients with PD (232 males and 189 females; mean age = 59.43 years) and 381 healthy controls (216 males and 165 females; mean age = 59.77 years). There were no significant differences between patients with PD and healthy controls regarding age (standardized mean difference = 0.018; 95% confidence interval = −0.114 to 0.151, z = 0.27, p = 0.786) or gender distribution (relative risk = 0.995, 95% CI = 0.925 to 1.070, z = 0.14, p = 0.891). Quality assessment indicated that the quality of these studies was acceptable because its score of each study was no less than 18 (total score = 20) (Table 1). The demographic, clinical, and imaging characteristics of each study included in this meta-analysis are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for inclusion/exclusion of studies.

Key: PD, Parkinson’s disease; ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations.

Table 1. Characteristics of ALFF studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Sample (female) | Mean Age (SD) | UPDRS-III (SD) | H&Y stage (SD) | Duration (SD) | Medication status | Scanner | Software | FWHM | Threshold | Quality scores# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwak et al.25 | PD 24 (2) HC 24 (5) | 64.3 (8) 63.3 (7) | 18.5 (8) | 2.2 (0.3) | 5.4 (3) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM5 | 8 mm | p < 0.001 uncorrected | 20 |

| Wen et al.19 | PD 16 (8) HC 21 (8) | 60.7 (18.7) 55.4 (16.4) | 33.8 (24.2) | 1.5 (1) | 5.6 (7.4) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM8, REST | 5 mm | p < 0.005 uncorrected | 20 |

| Possin et al.23 | PD 12 (9) HC 15 (11) | 73.9 (5.9) 72.9 (5.2) | 30.8 (14.5) | NA | 9 (7) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM8, REST | 4 mm | p < 0.05 corrected | 19 |

| Skidmore et al.13 | PD 14 (3) HC 15 (6) | 62 (9) 65 (13) | 37 (13) | NA | NA | Off-state | 3.0 T | AFNI | 6 mm | p < 0.005 uncorrected | 18 |

| Zhang et al.24 | PD 72 (37) HC 78 (32) | 59.7 (11.9) 58.6 (8.5) | 20.24 (8.44) | NA | 7.05 (6.01) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM8, REST | 8 mm | p < 0.05 corrected | 19 |

| Hou, et al.26 | PD 101 (42) HC 102 (42) | 59.84 (7.15) 59.91 (7.09) | 25.54 (11.51) | 1.87 (0.71) | 7.23 (4.42) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM8, DPARSF | 3 mm | p < 0.05 corrected | 20 |

| Luo et al.21 | PD 30 (15) HC 30 (15) | 53.64 (10.18) 51.9 (7.70) | 26.83 (12.44) | 1.73 (0.38) | 2.12 (1.30) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM8, REST | 8 mm | p < 0.001 corrected | 20 |

| Hu et al.17 | PD 17 (7) HC 20 (9) | 60.29 (12.03) 58.48 (6.89) | 17.11 (6.12) | NA | 3.94 (2.57) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM8, REST | 8 mm | p < 0.005 uncorrected | 19 |

| Chen et al.15 | PD1 12 (8) PD2 19 (7) HC 22 (10) | 62.6 (8.71) 64.8 (8.34) 65.1 (5.00) | 19.1 (11.5) 21.6 (11.6) | 1.87 (0.607) 2.13 (0.984) | 6.38 (4.01) 6.68 (4.85) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM8, REST | 4 mm | p < 0.05 corrected | 20 |

| Luo et al.18 | PD3 28 (14) PD4 28 (14) PD5 24 (11) HC 30 (15) | 52.45 (9.18) 54.12 (8.24) 54.41 (10.59) 53.53 (10.45) | 14.11 (6.45) 29.68 (8.22) 43.54 (12.65) | 1.0 (NA) 2.0 (NA) 3.0 (NA) | 1.56 (1.42) 3.78 (2.87) 5.31 (4.77) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM5, REST | 8 mm | p < 0.001 uncorrected | 19 |

| Xiang et al.27 | PD 24 (12) HC 24 (12) | 62.7 (7.4) 65.6 (6.9) | 22.0 (7.0) | 2.2 (0.9) | 7.0 (3.3) | Off-state | 3.0 T | SPM8, REST | 8 mm | p < 0.01 corrected | 20 |

Key: ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; PD, Parkinson’s disease; HC, healthy controls; SD, standard deviation; UPDRS-III, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, Part III; H&Y, Hoehn and Yahr disability scale; FWHM, full width at half maximum; NA, not available; AFNI, Analysis of Functional NeuroImage software; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; SPM, statistical parametric mapping; REST, the Resting-State fMRI Data Analysis Toolkit; 1postural instability/gait difficulty subtype of PD; 2tremor-dominant subtype of PD; 3PD patients at H&Y stage I; 4PD patients at H&Y stage II; 5PD patients at H&Y stage III; #a maximum score of 20 for each study.

ALFF differences of the voxel-wise meta-analysis

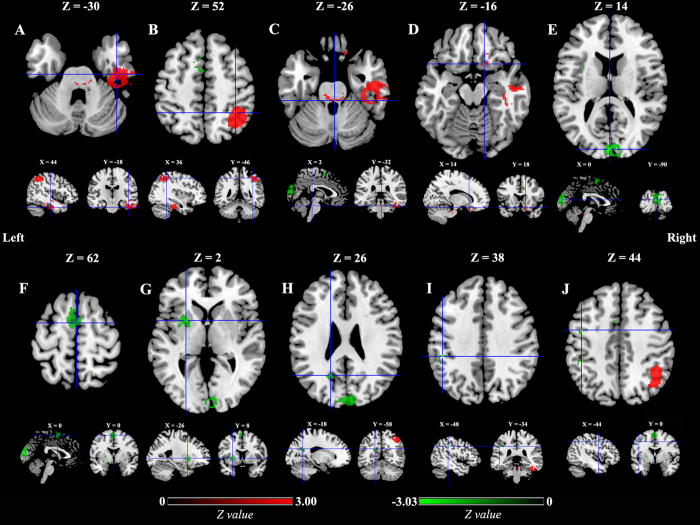

As shown in Figure 2, the voxel-wise meta-analysis identified increased ALFFs in the right inferior temporal gyrus extending to the middle temporal, fusiform, and parahippocampal gyri, right inferior parietal gyrus, right inferior parietal gyrus, brainstem (pons extending to midbrain), and right orbitofrontal cortex in patients with PD compared to healthy controls. In contrast, decreased ALFFs were observed in the bilateral cuneus cortices, bilateral cuneus cortices, bilateral supplementary motor areas (SMAs), left putamen, left inferior parietal gyrus, and left lateral premotor cortex. The details of the results are presented in Table 2.

Figure 2. ALFF differences in patients with PD compared to healthy controls.

Key: Red and green colors indicate increased and decreased ALFFs in patients with PD compared to healthy controls, respectively. ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; (A), Right inferior temporal/middle temporal/fusiform/parahippocampal gyri; (B), Right inferior parietal gyrus; (C), Brainstem (pons and midbrain); (D), Right orbitofrontal cortex; (E), Left/Right cuneus cortices; (F), Left/Right supplementary motor areas; (G), Left putamen; (H), Left cuneus cortex; (I), Left inferior parietal gyrus; (J), Left lateral premotor cortex.

Table 2. ALFF differences in patients with PD compared to healthy controls.

| Cluster | Anatomical label | Peak MNI coordinate (x, y, z) | No. of voxels | SDM-Z value | p value | Heterogeneity | Egger’s test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD > HC | |||||||

| A | Right inferior temporal/middle temporal/fusiform parahippocampal gyri (BA 20) | 44, −18, −30 | 790 | 3.00 | 0.000015 | Yes | <0.001 |

| B | Right inferior parietal gyrus (BAs 39, 40, and 7) | 36, −46, 52 | 740 | 2.81 | 0.000062 | No | 0.172 |

| C | Brainstem (pons and midbrain) | 2, −32, −26 | 51 | 2.16 | 0.0011 | Yes | 0.046 |

| D | Right orbitofrontal cortex (BA 11) | 14, 18, −16 | 46 | 1.92 | 0.0029 | No | 0.018 |

| PD < HC | |||||||

| E | Left/Right cuneus cortices (BAs 18, 17, and 19) | 0, −90, 14 | 641 | −3.03 | 0.000040 | No | 0.002 |

| F | Left/Right supplementary motor areas (BA 6) | 0, 0, 62 | 352 | −2.44 | 0.00080 | No | 0.500 |

| G | Left putamen | −26, 8, 2 | 187 | −2.45 | 0.00078 | No | 0.186 |

| H | Left cuneus cortex (BA 23) | −18, −58, 26 | 43 | −2.21 | 0.0018 | Yes | 0.140 |

| I | Left inferior parietal gyrus (BAs 40 and 2) | −48, −34, 38 | 30 | −2.07 | 0.0030 | No | 0.065 |

| J | Left lateral premotor cortex (BA 6) | −44, 0, 44 | 26 | −2.07 | 0.0029 | No | 0.058 |

Key: ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; PD, Parkinson’s disease; HC, healthy controls; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; BA, Brodmann area; No., number; SDM, Seed-based d Mapping.

Analyses of jackknife sensitivity, heterogeneity, and publication bias

The jackknife sensitivity analysis (Table 3) revealed that regions of ALFF differences in the right inferior temporal gyrus extending to the middle temporal, fusiform, and parahippocampal gyri, right inferior parietal gyrus, and bilateral cuneus cortices (BAs 18, 17, and 19) were replicable in all 14 datasets. Regions of ALFF differences in the brainstem, right orbitofrontal cortex, bilateral SMAs, left putamen, left inferior parietal gyrus, and left lateral premotor cortex were replicable in at least 12 datasets. While a brain region in the left cuneus cortex (BA 23) was only replicable in 10 datasets. The heterogeneity analysis revealed significant unexplained between-study variability of ALFF changes in widespread brain regions, including the left superior temporal gyrus extending to the middle temporal gyrus and insula, right caudate nucleus, right fusiform gyrus extending to the inferior temporal gyrus, right cerebellum (lobule VI), brainstem (pons), left cerebellum (crus I), right striatum, right inferior frontal gyrus, left superior occipital gyrus, left cuneus cortex (BA 23), right inferior temporal gyrus, right cerebellum (lobule IV/V), and left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) (Supplementary Table 3). In addition, publication bias examined by the Egger’s test was detected in the regions of ALFF differences in the right inferior temporal gyrus extending to middle temporal, fusiform, and parahippocampal gyri (p < 0.001), brainstem (p = 0.046), right orbitofrontal cortex (p = 0.018), and bilateral cuneus cortices (p = 0.002). No publication bias was identified in other regions obtained from the voxel-wise meta-analysis (Table 2).

Table 3. Jackknife sensitivity analysis.

| All studies but … | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwak et al.25 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wen et al.19 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Possin et al.23 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Skidmore et al.13 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zhang et al.24 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hou, et al.26 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Luo et al.21 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hu et al.17 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chen et al.a 15 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chen et al.b 15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Luo et al.c 18 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Luo et al.d 18 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Luo et al.e 18 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Xiang et al.27 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Total | 14 out of 14 | 14 out of 14 | 12 out of 14 | 12 out of 14 | 14 out of 14 | 13 out of 14 | 13 out of 14 | 10 out of 14 | 13 out of 14 | 12 out of 14 |

Key: A, Right inferior temporal/middle temporal/fusiform/parahippocampal gyri; B, Right inferior parietal gyrus; C, Brainstem (pons and midbrain); D, Right orbitofrontal cortex; E, Left/Right cuneus cortices; F, Left/Right supplementary motor areas; G, Left putamen; H, Left cuneus cortex; I, Left inferior parietal gyrus; J, Left lateral premotor cortex; Yes, the region reported; No, the region not reported; apostural instability/gait difficulty subtype of PD; btremor-dominant subtype of PD; cPD patients at H&Y stage I; dPD patients at H&Y stage II; ePD patients at H&Y stage III.

Meta-regression analyses

Meta-regression analysis revealed that the PD group with older mean age (available in all datasets) exhibited greater ALFFs in the right inferior temporal gyrus extending to the middle temporal, fusiform, and parahippocampal gyri, right inferior parietal gyrus and lesser ALFFs in the bilateral cuneus cortices. Higher average H&Y stage in the PD group (available in 10 datasets) was associated with greater ALFFs in the bilateral precuneus/PCC and right inferior parietal gyrus. Higher average UPDRS-III score in the PD group (available in all datasets) correlated with greater ALFFs in the right inferior parietal gyrus and bilateral precuneus/PCC, and lesser ALFFs in the bilateral SMAs. Regression analysis indicated that longer mean illness duration of PD patients (available in 13 datasets) was associated with greater ALFFs in the right fusiform/inferior temporal gyri. The results of these meta-regression analyses are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Meta-regression analyses.

| Anatomical label | Peak MNI coordinate (x, y, z) | No. of voxels | SDM-Z value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of age: ALFF changes in studies with older patients compared to younger patients | ||||

| Right inferior temporal/middle temporal/fusiform/parahippocampal gyri (BA 20) | 44, −16, −28 | 169 | 2.193 | 0.0000305 |

| Right/Left cuneus cortices (BAs 18 and 17) | 6, −98, 10 | 106 | −2.695 | 0.0000361 |

| Effects of motor severity: ALFF changes in studies with higher average UPDRS-III score | ||||

| Right inferior parietal gyrus (BAs 39, 40, and 7) | 40, −50, 48 | 811 | 3.567 | ~0 |

| Left/Right precuneus/PCC (BAs 23 and 30) | −16, −90, 38 | 61 | 2.759 | 0.0000439 |

| Right/Left supplementary motor area (BA 6) | 2, 10, 60 | 223 | −2.114 | 0.000150 |

| Effects of illness severity: ALFF changes in studies with higher average H&Y stage | ||||

| Left/Right precuneus/PCC (BAs 23 and 30) | −4, −46, 32 | 322 | 2.405 | 0.000214 |

| Right inferior parietal gyrus (BAs 39, 40, and 7) | 38, −54, 46 | 200 | 2.643 | 0.0000718 |

| Effects of illness duration: ALFF changes in studies with longer average illness duration | ||||

| Right fusiform/inferior temporal gyri (BA 20) | 40, −20, −28 | 125 | 3.830 | 0.0000279 |

Key: ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; PD, Parkinson’s disease; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; No., number; SDM, Seed-based d Mapping; BA, Brodmann area; UPDRS-III, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, Part III; H&Y, Hoehn and Yahr disability scale; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex.

Discussion

In the present study, we conducted a meta-analysis to identify the most consistent and reliable ALFF changes in PD. Besides the main voxel-based meta-analysis, several complementary analyses, such as jackknife sensitivity, heterogeneity, and publication bias analyses were performed to explore the robustness of the findings. These comprehensive analyses showed that decreased ALFFs in the bilateral SMAs, left putamen, left lateral premotor cortex, and left inferior parietal gyrus and increased ALFFs in the right inferior parietal gyrus were the most consistent and reliable findings in patients with PD compared to healthy controls. Further meta-regression analyses indicated an effect of motor severity on ALFF changes in the bilateral SMAs and right inferior parietal gyrus, and illness severity on ALFF changes in the right inferior parietal gyrus.

Cardinal motor impairments characterize PD and dysfunction of the cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical motor circuits is a fundamental model implicated in its pathophysiology45. Our meta-analysis consistently identified decreased ALFFs in the left putamen, bilateral SMAs, and left lateral premotor cortex. Decreased ALFFs are considered to reflect local spontaneous neuronal hypoactivity in these regions and indicate disease-related functional deficits secondary to degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal system45,46. Neuronal neurodegeneration, dopaminergic deficits, hypo-metabolism, and hypoactivation of the putamen have been convergently confirmed in PD45,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. The putamen has dense anatomical and functional connections with motor cortical areas in normal humans55,56,57. While less functional connectivity between the putamen and cortical motor areas was observed in PD patients58,59.

Hypoactivity in the SMA in our meta-analysis is well in line with previous task-related and resting-state fMRI, and positron emission tomography (PET) studies51,52,60,61,62 and could be modulated by dopaminergic treatment in patients with PD52,61,63. However, brain activation (hypoactivity or hyperactivity) in the lateral premotor cortex has not been always consistent in task-related fMRI or PET studies62,63,64,65,66. A recent meta-analysis including 24 fMRI and PET studies in PD patients with motor tasks even could not detect consistent cortical activation in the lateral premotor cortex67. The activation inconsistences may attribute to task-specific recruitment of cortical motor areas or heterogeneity in task performance performed in enrolled patients. Rs-fMRI avoids any confound of variable task performance and can be easily implemented to obtain relatively stable results. The SMA is well known to play a critical role in internal motor preparation and execution63,68, whereas the lateral premotor cortex is involved more with externally guided movements69. SMA is a therapeutic target for PD management and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over the SMA has been shown to be effective for improving motor symptoms70,71. Moreover, our meta-analysis revealed that severer motor deficits in the PD group correlated with lesser ALFFs in the bilateral SMAs. Whether ALFF changes in the SMAs could serve as a prognostic imaging marker merits further investigations. Our meta-analysis together with previous studies suggests that resting-state hypoactivation in the putamen, SMA, and premotor may contribute to the cardinal motor signs underlying PD.

Interestingly, the present study observed an asymmetrical activation in the inferior parietal cortex. Analysis of anatomical connectivity using probabilistic tractography shows that the rostral inferior parietal areas were predominantly connected to inferior frontal, motor, premotor, and somatosensory areas involved in higher motor functions, whereas the caudal areas are more strongly connected with posterior parietal, higher visual and temporal areas related to spatial attention and language processing72,73,74. Our meta-analysis identified hypoactivation in the left rostral inferior parietal cortex (BA 40) and hyperactivation in the right caudal inferior parietal cortex (mainly BA39) with a differential functional involvement. Previous task-related fMRI or PET studies also observed abnormal activation or connectivity of the rostral inferior parietal cortex (BA 40) in patients with PD65,66,69,75. In addition, rs-fMRI data in PD patients showed abnormal functional connectivity between the putamen and the inferior parietal cortex (BA 40)76. Whereas the caudal inferior parietal cortex (BA39) is an important hub of the default mode network (DMN), which is one of the most investigated resting-state networks, involved in higher cognitive processes77. Although heterogenous in the meta-analysis, other regions such as the right inferior temporal gyrus extending to the middle temporal, fusiform, and parahippocampal gyri, and precuneus/PCC observed were also the components of the DMN77,78. Tessitore et al. found a decreased resting-state functional connectivity of the right medial temporal lobe and bilateral inferior parietal cortex within the DMN even in cognitively unimpaired patients with PD79. Furthermore, they showed significant positive correlations between this decreased DMN connectivity and cognitive parameters such as memory test and visuospatial scores79. Regional spontaneous hyperactivation in the caudal inferior parietal cortex may reflect a compensatory way for the remote decreased functional connectivity. However, regional hyperactivation in this region may compensate more for the motor impairment in PD patients because our meta-analyses indicated that both increased motor severity and illness severity correlated with greater hyperactivation in this area.

Other regions are highly heterogenous or not robust detected in the meta-analysis. Besides the unexplained between-study variability of ALFF changes in the right inferior temporal gyrus extending to the middle temporal, fusiform, and parahippocampal gyri (BA 20), brainstem (pons and midbrain), and left cuneus cortex (BA 23), several moderator variables contributed to understanding the source of the heterogeneity. Of these, mean age in the PD group had a significant effect on the ALFF changes in the right inferior temporal gyrus extending to the middle temporal, fusiform, and parahippocampal gyri (BA 20), and bilateral cuneus cortices (BAs 18 and 17). In addition, we noted that the PD group with longer mean illness duration tended to have greater ALFF changes in the right fusiform extending to the inferior temporal gyri (BA 20). We also observed that decreased ALFFs in the left cuneus cortex (BA 23) were replicable only in 10 out of the 14 datasets as revealed by the jackknife sensitivity analysis. Unlike other coordinate-based meta-analytic methods for neuroimaging data, such as the activationlikelihoodestimation67,80 and multilevel kernel density analyses81,82, the SDM offers comprehensive information about robustness of the findings28,30,83. The present study suggests that future meta-analysis of neuroimaging data would benefit from complementary analyses to minimize the risk of false positives30,83.

Limitations and perspectives

Despite the strengths, several limitations of the present meta-analysis should be acknowledged. First, SDM is a coordinate-based rather than an image-based meta-analytic method, which might lead to less accurate results that is also inherent to other coordinate-based meta-analytic approaches28,80,82,83. However, it is more difficult to obtain original imaging data than reported peak coordinates from original studies. Second, some potential methodological heterogeneity, such as different image analytical procedures (frequency differences, ALFF and fractional ALFF analyses)17,23,24,26 existed across studies. We could not further conduct subgroup analyses because of the limited number of eligible studies for controlling these moderator variables. Third, the ALFF studies in our meta-analyses mainly included Chinese samples, which might limit the findings to other populations. Further studies with more efforts are warranted to apply the ALFF method to other samples. Fourth, although ALFF is thought to reflect regional spontaneous neuronal activity, its exact neurobiological basis remains to be fully elucidated84. Future studies with multimodal imaging techniques and analysis approaches may provide more insights about the function-structure associations of the PD brain85.

Conclusions

Using the comprehensive meta-analytic approach, we identified the most consistent and reliable ALFF changes, including decreased ALFFs in the bilateral SMAs, left putamen, left premotor cortex, and left inferior parietal gyrus, and increased ALFFs in the right inferior parietal gyrus in patients with PD compared to healthy controls. The altered ALFFs in these brain regions may be related to motor deficits and compensation in PD, which could serve as specific regions of interest for further studies. Other highly heterogenous or not robust regions, such as right inferior temporal gyrus extending to the middle temporal, fusiform and parahippocampal gyri, brainstem (pons and midbrain), right orbitofrontal cortex, and bilateral cuneus cortices merit further investigations.

Methods

Identification, selection, and quality assessment of studies

We comprehensively searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science databases for studies published between January 1st, 2000 and June 24, 2016 using the following keywords “Parkinson” OR “Parkinson’s disease”, AND “amplitude of low frequency fluctuations” OR “ALFF”. Other resources, such as the reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles were additionally identified. Studies were included if they satisfied the following conditions: (i) they were published in English as an original article in a peer-reviewed journal; (ii) they reported ALFF results at the whole-brain level for direct comparison between patients with idiopathic PD and healthy controls; (iii) they reported negative results or three-dimensional coordinates in a standardized stereotaxic space for regions with significant differences; (iv) they reported significant results using thresholds for significance corrected for multiple comparisons or uncorrected with spatial extent thresholds. In order to reduce the heterogeneity, studies were excluded if they explicitly indicated patients with PD diagnosed with comorbid neurological or psychiatric disorders (i.e., depression, visual hallucinations, or cognitive impairment) or if they only reported the on-state results. The baseline result was included if the study was longitudinal. In cases where multiple articles were identified to use the overlapped patient datasets, the one with the largest sample size and the most comprehensive information was selected. The quality of each study included in this meta-analysis was assessed according to a 20-point checklist developed for rs-fMRI studies30 (see Supplementary Table 2). Literature search, study assessment and selection, and data extraction with a standard form were independently performed by two authors (P.L.P and Y.Z.). Any discrepancies were discussed with a third researcher for a final decision (Y.L.). The Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines were followed in this study86.

Data analysis

Voxel-wise meta-analysis

This voxel-wise meta-analysis was carried out using the SDM software package available at http://www.sdmproject.com. The details of the approach have been described elsewhere28,31,32,33 First, we extracted peak coordinates and effect sizes (t-values) of ALFF differences between patients with PD and healthy controls from each dataset. Second, an effect-size signed map of the ALFF differences was then separately recreated for each dataset. SDM calculates both positive and negative differences between datasets in the same map31,33. And third, the mean map was generated by voxel-wise calculation of the random-effects mean of the dataset maps, which was weighted by the sample size, intra-dataset variability, and additional between-dataset heterogeneity. Default SDM settings (full width at half maximum [FWHM] = 20 mm, p = 0.005, peak height Z = 1, cluster extent = 10 voxels), which were found to optimally balance false positives and negatives, were applied to the results31,33.

Analyses of jackknife sensitivity, heterogeneity, and publication bias

To assess the replicability of the results, a jackknife sensitivity analysis was performed by iteratively repeating the same analysis, excluding one dataset each time28,31.

In addition, a heterogeneity analysis was conducted using a random effects model with Q statistics to explore unexplained between-study variability in the results. These analyses were thresholded with the default SDM settings (FWHM = 20 mm, p = 0.005, peak height Z = 1, cluster extent = 10 voxels)31,33.

In order to evaluate possible publication bias, the Stata/SE 12.0 software for Windows (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used to perform the Egger’s test by extracting the values from the peak coordinates of the voxel-wise meta-analysis between patients with PD and healthy controls87. Statistical significance was thresholded at a p-value less than 0.05.

The Stata/SE 12.0 software was additionally used to meta-analyze mean age and gender distribution in the PD groups and control groups across studies with a random-effects model to test whether there is heterogeneity.

Meta-regression analyses

Meta-regression analyses were carried out to explore the effects of age, illness severity (Hoehn and Yahr [H&Y] stage), motor severity (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Part III [UPDRS-III] score), and illness duration, which could potentially influence the analytic results. P-value less than 0.0005 and cluster extent more than 10 voxels were considered statistically significant31,32.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Pan, P. L. et al. Abnormalities of regional brain function in Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis of resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Sci. Rep. 7, 40469; doi: 10.1038/srep40469 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the authors of the included studies. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81230026, 81171085, 81300924, 81601161), the Natural Science Foundation (BL2012013) and the Bureau of Health (LJ201101) of Jiangsu Province of China.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.X. conceived the project. P.L.P. and Y.Z. designed the protocol and wrote the main manuscript. P.L.P., Y.Z. and Y.L. obtained the data. P.L.P., H.Z. and Y.Z. analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript. D.N.G. and Y.X. revised the manuscript.

References

- Findley L. J. The economic impact of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & related disorders 13 Suppl, S8–S12, doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.003 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringsheim T., Jette N., Frolkis A. & Steeves T. D. The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 29, 1583–1590, doi: 10.1002/mds.25945 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia L. V. & Lang A. E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 386, 896–912, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A. Q., Ahmed U. S., Chaudry Z. M. & Vasan S. Parkinson’s disease: a review of non-motor symptoms. Expert review of neurotherapeutics 15, 549–562, doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1038244 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W. & Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron 39, 889–909 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten C. P., Sundman M. H., Hickey P. & Chen N. K. Neuroimaging of Parkinson’s disease: Expanding views. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 59, 16–52, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodoehl J., Burciu R. G. & Vaillancourt D. E. Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging in Parkinson’s disease. Current neurology and neuroscience reports 14, 448, doi: 10.1007/s11910-014-0448-6 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Q. H. et al. An improved approach to detection of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) for resting-state fMRI: fractional ALFF. Journal of neuroscience methods 172, 137–141, doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.04.012 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren W. et al. Anatomical and functional brain abnormalities in drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry 170, 1308–1316, doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12091148 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W. B. et al. Alterations of the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in treatment-resistant and treatment-response depression: a resting-state fMRI study. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry 37, 153–160, doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.01.011 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P. et al. Altered amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in early and late mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer research 11, 389–398 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. et al. Frequency-dependent changes in the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a resting-state fMRI study. NeuroImage 55, 287–295, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.059 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore F. M. et al. Reliability analysis of the resting state can sensitively and specifically identify the presence of Parkinson disease. Neuroimage 75, 249–261, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.056 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. et al. Pathological uncoupling between amplitude and connectivity of brain fluctuations in epilepsy. Human brain mapping 36, 2756–2766, doi: 10.1002/hbm.22805 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. M. et al. Different patterns of spontaneous brain activity between tremor-dominant and postural instability/gait difficulty subtypes of Parkinson’s disease: a resting-state fMRI study. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics 21, 855–866, doi: 10.1111/cns.12464 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore F. M. et al. Apathy, depression, and motor symptoms have distinct and separable resting activity patterns in idiopathic Parkinson disease. NeuroImage 81, 484–495, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.012 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. F. et al. Amplitude of low-frequency oscillations in Parkinson’s disease: a 2-year longitudinal resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Chinese medical journal 128, 593–601, doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.151652 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C. et al. The trajectory of disturbed resting-state cerebral function in Parkinson’s disease at different Hoehn and Yahr stages. Human brain mapping 36, 3104–3116, doi: 10.1002/hbm.22831 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X., Wu X., Liu J., Li K. & Yao L. Abnormal baseline brain activity in non-depressed Parkinson’s disease and depressed Parkinson’s disease: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. PLoS One 8, e63691, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063691 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. et al. Apolipoprotein E4 affects topographical changes in hippocampal and cortical atrophy in alzheimer’s disease dementia: A five-year longitudinal study. Neurodegenerative Diseases 15, 463 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C. et al. Resting-state fMRI study on drug-naive patients with Parkinson’s disease and with depression. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 85, 675–683, doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306237 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao N. et al. Resting activity in visual and corticostriatal pathways in Parkinson’s disease with hallucinations. Parkinsonism & related disorders 21, 131–137, doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.11.020 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possin K. L. et al. Rivastigmine is associated with restoration of left frontal brain activity in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 28, 1384–1390 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. Specific frequency band of amplitude low-frequency fluctuation predicts Parkinson’s disease. Behavioural brain research 252, 18–23, doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.039 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak Y. et al. L-DOPA changes spontaneous low-frequency BOLD signal oscillations in Parkinson’s disease: a resting state fMRI study. Frontiers in systems neuroscience 6, 52, doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2012.00052 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y., Wu X., Hallett M., Chan P. & Wu T. Frequency-dependent neural activity in Parkinson’s disease. Human brain mapping 35, 5815–5833, doi: 10.1002/hbm.22587 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang J. et al. Altered Spontaneous Brain Activity in Cortical and Subcortical Regions in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson’s disease 2016, 5246021, doi: 10.1155/2016/5246021 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radua J. & Mataix-Cols D. Voxel-wise meta-analysis of grey matter changes in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry 195, 393–402, doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055046 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L. et al. Motor and extra-motor gray matter atrophy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: quantitative meta-analyses of voxel-based morphometry studies. Neurobiology of aging 36, 3288–3299, doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.08.018 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabuchi S. J. et al. Localized connectivity in depression: a meta-analysis of resting state functional imaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 51, 77–86, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.006 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radua J. et al. Anisotropic kernels for coordinate-based meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies. Front Psychiatry 5, 13, doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00013 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radua J. et al. A new meta-analytic method for neuroimaging studies that combines reported peak coordinates and statistical parametric maps. European psychiatry: the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists 27, 605–611, doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.04.001 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim L., Radua J. & Rubia K. Gray matter abnormalities in childhood maltreatment: a voxel-wise meta-analysis. The American journal of psychiatry 171, 854–863, doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101427 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H. I., Radua J., Luckmann H. C. & Sack A. T. Meta-analysis of functional network alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: toward a network biomarker. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 37, 753–765, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.03.009 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Pan P., Huang R. & Shang H. A meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies of white matter volume alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 36, 757–763, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.001 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan P. L., Song W. & Shang H. F. Voxel-wise meta-analysis of gray matter abnormalities in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. European journal of neurology 19, 199–206, doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03474.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welton T., Kent D., Constantinescu C. S., Auer D. P. & Dineen R. A. Functionally relevant white matter degradation in multiple sclerosis: a tract-based spatial meta-analysis. Radiology 275, 89–96, doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140925 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansley J., Mataix-Cols D., Grau M., Radua J. & Sastre-Garriga J. Localized grey matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies and associations with functional disability. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 37, 819–830, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.03.006 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. et al. A meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging studies in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiology of aging 33, 1833–1838, doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.04.007 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E., Fornito A., Pantelis C. & Yucel M. Gray matter abnormalities in Major Depressive Disorder: a meta-analysis of voxel based morphometry studies. Journal of affective disorders 138, 9–18, doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.049 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C., Song W., Guo X., Shang H. & Gong Q. The trajectory of disturbed resting-state cerebral function in Parkinson’s disease at different Hoehn & Yahr stages. Movement Disorders 30, S16–S17 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. et al. Abnormal amygdala function in Parkinson’s disease patients and its relationship to depression. Journal of affective disorders 183, 263–268, doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.029 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long D. et al. Automatic classification of early Parkinson’s disease with multi-modal MR imaging. PLoS One 7, e47714, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047714 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. et al. Altered Resting-State Brain Activity and Connectivity in Depressed Parkinson’s Disease. PloS one 10, e0131133, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131133 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A. & Wichmann T. Pathophysiology of parkinsonism. Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology 119, 1459–1474, doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.017 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbach D. & Bishop C. Critical involvement of the motor cortex in the pathophysiology and treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37, 2737–2750, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.09.008 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka M. et al. Differences in the reduced 18F-Dopa uptakes of the caudate and the putamen in Parkinson’s disease: correlations with the three main symptoms. Journal of the neurological sciences 136, 169–173 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonini A. et al. Complementary positron emission tomographic studies of the striatal dopaminergic system in Parkinson’s disease. Archives of neurology 52, 1183–1190 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrish P. K., Sawle G. V. & Brooks D. J. Regional changes in [18F]dopa metabolism in the striatum in Parkinson’s disease. Brain : a journal of neurology 119(Pt 6), 2097–2103 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. et al. Abnormal fronto-striatal functional connectivity in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience letters 613, 66–71, doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.12.041 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Sternad D., Corcos D. M. & Vaillancourt D. E. Role of hyperactive cerebellum and motor cortex in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroImage 35, 222–233, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.047 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. et al. Regional homogeneity changes in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Human brain mapping 30, 1502–1510, doi: 10.1002/hbm.20622 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruck A. et al. Striatal subregional 6-[18F]fluoro-L-dopa uptake in early Parkinson’s disease: a two-year follow-up study. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 21, 958–963, doi: 10.1002/mds.20855 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish S. J., Shannak K. & Hornykiewicz O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. N Engl J Med 318, 876–880, doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804073181402 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draganski B. et al. Evidence for segregated and integrative connectivity patterns in the human Basal Ganglia. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 28, 7143–7152, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1486-08.2008 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postuma R. B. & Dagher A. Basal ganglia functional connectivity based on a meta-analysis of 126 positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging publications. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991) 16, 1508–1521, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj088 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehericy S. et al. Diffusion tensor fiber tracking shows distinct corticostriatal circuits in humans. Annals of neurology 55, 522–529, doi: 10.1002/ana.20030 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. et al. Changes of functional connectivity of the motor network in the resting state in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience letters 460, 6–10, doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.05.046 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. et al. Effective connectivity of brain networks during self-initiated movement in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroImage 55, 204–215, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.074 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payoux P. et al. Motor activation in multiple system atrophy and Parkinson disease: a PET study. Neurology 75, 1174–1180, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d78f (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhmann C. et al. Pharmacologically modulated fMRI–cortical responsiveness to levodopa in drug-naive hemiparkinsonian patients. Brain: a journal of neurology 126, 451–461 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Wang L., Hallett M., Li K. & Chan P. Neural correlates of bimanual anti-phase and in-phase movements in Parkinson’s disease. Brain: a journal of neurology 133, 2394–2409, doi: 10.1093/brain/awq151 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslinger B. et al. Event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging in Parkinson’s disease before and after levodopa. Brain: a journal of neurology 124, 558–570 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Tang C., Spetsieris P. G., Dhawan V. & Eidelberg D. Abnormal metabolic network activity in Parkinson’s disease: test-retest reproducibility. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 27, 597–605, doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600358 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. et al. Metabolic brain networks associated with cognitive function in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroImage 34, 714–723, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.003 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini U. et al. Cortical motor reorganization in akinetic patients with Parkinson’s disease: a functional MRI study. Brain: a journal of neurology 123(Pt 2), 394–403 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz D. M., Eickhoff S. B., Lokkegaard A. & Siebner H. R. Functional neuroimaging of motor control in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Human brain mapping 35, 3227–3237, doi: 10.1002/hbm.22397 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. M., Chang K. H. & Roh J. K. Subregions within the supplementary motor area activated at different stages of movement preparation and execution. NeuroImage 9, 117–123, doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0393 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel M. et al. Evidence for lateral premotor and parietal overactivity in Parkinson’s disease during sequential and bimanual movements. A PET study. Brain: a journal of neurology 120(Pt 6), 963–976 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirota Y. et al. Supplementary motor area stimulation for Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled study. Neurology 80, 1400–1405, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828c2f66 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M., Ugawa Y. & Tsuji S. Effectiveness of rTms on Parkinson’s Disease Study Group, J. High-frequency rTMS over the supplementary motor area for treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 23, 1524–1531, doi: 10.1002/mds.22168 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S. et al. Probabilistic fibre tract analysis of cytoarchitectonically defined human inferior parietal lobule areas reveals similarities to macaques. NeuroImage 58, 362–380, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.027 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S. et al. Organization of the human inferior parietal lobule based on receptor architectonics. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991) 23, 615–628, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs048 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S. et al. The human inferior parietal lobule in stereotaxic space. Brain structure & function 212, 481–495, doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0195-z (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccini P. et al. Delayed recovery of movement-related cortical function in Parkinson’s disease after striatal dopaminergic grafts. Annals of neurology 48, 689–695 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmich R. C. et al. Spatial remapping of cortico-striatal connectivity in Parkinson’s disease. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991) 20, 1175–1186, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp178 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Hanna J. R., Reidler J. S., Sepulcre J., Poulin R. & Buckner R. L. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain’s default network. Neuron 65, 550–562, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.005 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner R. L., Andrews-Hanna J. R. & Schacter D. L. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1124, 1–38, doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessitore A. et al. Default-mode network connectivity in cognitively unimpaired patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology 79, 2226–2232, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827689d6 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff S. B., Bzdok D., Laird A. R., Kurth F. & Fox P. T. Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis revisited. NeuroImage 59, 2349–2361, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.017 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo S., Bianchi-Demicheli F., Frum C., Pfaus J. G. & Lewis J. W. The common neural bases between sexual desire and love: a multilevel kernel density fMRI analysis. The journal of sexual medicine 9, 1048–1054, doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02651.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager T. D., Lindquist M. A., Nichols T. E., Kober H. & Van Snellenberg J. X. Evaluating the consistency and specificity of neuroimaging data using meta-analysis. NeuroImage 45, S210–221, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.061 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radua J. & Mataix-Cols D. Meta-analytic methods for neuroimaging data explained. Biology of mood & anxiety disorders 2, 6, doi: 10.1186/2045-5380-2-6 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. et al. Anatomical and functional deficits in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. PloS one 7, e28664, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028664 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui J., Huster R., Yu Q., Segall J. M. & Calhoun V. D. Function-structure associations of the brain: evidence from multimodal connectivity and covariance studies. NeuroImage 102Pt 1, 11–23, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.09.044 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup D. F. et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama 283, 2008–2012 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radua J. et al. Multimodal voxel-based meta-analysis of white matter abnormalities in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 1547–1557, doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.