CASE

A 61-year-old male with relapsed multiple myeloma presented to clinic with fatigue and chills. The patient had undergone two rounds of autologous stem cell transplantation in 2012 and was undergoing chemotherapy with pomalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone. He was admitted for neutropenic fever (absolute neutrophil count of 1.4 × 109/liter, temperature of 38.4°C). His physical exam was normal, and he denied any other symptoms. Two sets of blood cultures were obtained (VersaTREK Redox; Trek Diagnostic Systems), and the patient was started on levofloxacin, vancomycin, and cefepime. His fever subsided after 24 h, and he was discharged home to complete a 30-day course of oral levofloxacin.

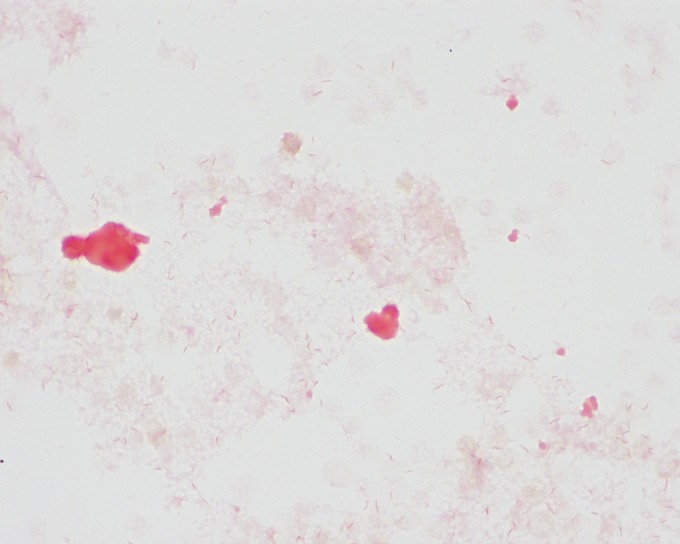

After 2.5 days of incubation, aerobic bottles from both blood culture sets were positive for growth of a curved Gram-negative bacillus with a morphology resembling “gull wings” (Fig. 1). Subculture to Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood (TSA-B) and chocolate agar was performed, and media were incubated at 35°C with 5% CO2. Subculture to brucella agar (with blood, hemin, and vitamin K) was also performed, and the culture was incubated anaerobically (all media from Remel). Because of the Gram stain morphology, subculture to Campylobacter CVA blood agar (Hardy Diagnostics) was performed, and the culture was incubated at 42°C under microaerobic conditions (6% O2, 7.2% CO2, 7.2% H2, and 79.7% N2 in an Anoxomat jar). All four media were negative for growth after 7 days of incubation. To establish the etiology of infection, broad-range 16S rRNA gene PCR and sequencing were performed directly on the positive blood culture broth (1). The bacterium was identified as Helicobacter cinaedi with 100% identity to multiple H. cinaedi sequences, including the type strain (ATCC strain BAA-847), by a standard nucleotide BLAST search (NCBI).

FIG 1.

Gram stain of H. cinaedi grown in aerobic blood culture broth (VersaTREK).

Once the identification was established, subculture was repeated using buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE), brain heart infusion with sheep blood (BHI-B), and brucella agars incubated under microaerobic conditions at 35°C. Pinpoint growth was observed on all three types of media after 48 h of incubation. There are no interpretive criteria for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Helicobacter cinaedi. However, MICs were determined by gradient diffusion on BHI-B agar using Etests (bioMérieux) incubated under microaerobic conditions for 48 h. The observed MICs were 16 μg/ml for levofloxacin, 2 μg/ml for clarithromycin, and 0.25 μg/ml for tetracycline, with testing for these specific antimicrobials performed at the request of the treating physician.

The patient returned to the same clinic 8 days after discharge, reporting fatigue and dizziness. He was afebrile (36.8°C) but neutropenic and was given intravenous hydration. Two sets of blood cultures were obtained. Levofloxacin was discontinued, and both ceftriaxone and doxycycline were initiated at this time. Importantly, identification of the patient's blood culture isolate by 16S rRNA gene sequencing had been reported 1 day prior to the patient's re-presentation. The patient was managed in the outpatient setting, and the following day, he reported mild clinical improvement. He also received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) to stimulate the production of neutrophils. After 2.8 days, the aerobic bottles of both blood culture sets were again positive for gull-shaped Gram-negative bacilli. Pinpoint growth was observed on TSA-B and chocolate agar after 48 h of incubation at 35°C under microaerobic conditions, and the organism was identified as H. cinaedi by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry using the Bruker RUO database, with a score of 2.102 (Bruker Biotyper; Bruker Daltonics). Seven days after his second clinic visit, the patient had recovered clinically and denied further symptoms. He successfully completed his 2-week course of ceftriaxone and doxycycline with no recurrence of symptoms through 8 months of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Helicobacter cinaedi is an “enterohepatic” Helicobacter species, a group that also includes H. bilis, H. canadensis, H. canis, H. fennelliae, and H. pullorum (2). These organisms inhabit the intestinal and hepatobiliary tracts of various mammal and bird hosts and are thought to translocate across the intestinal barrier to cause invasive infections. Importantly, bacteremia is the most common human infection noted for enterohepatic Helicobacter species, although other infections have also been observed with this group (e.g., H. pullorum and gastroenteritis). While transmission is not fully understood, the primary hosts for these organisms may be rodents, dogs, and other primates. Human carriage of H. cinaedi was first discovered in 1984, where it was isolated from rectal cultures of men who have sex with men. Since then, a variety of infections with H. cinaedi have been described, including bacteremia, infected aortic aneurysm, cellulitis, proctocolitis, gastroenteritis, meningitis, and osteomyelitis (2). While H. cinaedi is generally considered to be an opportunistic pathogen of the immunosuppressed, infection of immunocompetent individuals has also been described (2).

Interestingly, cellulitis can often be observed among patients who are bacteremic with H. cinaedi, although no cellulitis was noted in our patient. The true frequency of H. cinaedi bacteremia globally is not well understood, with the majority of the literature assessing this issue originating from Japan; H. cinaedi accounted for 2.2% (126/5,769) of positive blood culture cases in one study (3), while a multicenter study from 13 hospitals in Tokyo reported H. cinaedi in 0.22% of positive blood cultures over a 6-month period (2). It is possible that bacteremia with H. cinaedi may go undetected in many cases, with 45% of bacteremic patients requiring a blood culture incubation period longer than 5 days in the largest case series published to date (3). There may be differences between commercially available blood culture systems in their ability to recover H. cinaedi. As reported by one laboratory in Japan, 23 blood culture samples were positive for H. cinaedi in a 2-year period using the Bactec system (Becton Dickinson), while no H. cinaedi was isolated in the preceding 3 years using the BacT/Alert system (bioMérieux) (4). A follow-up study demonstrated that the Bactec system was positive for growth following the inoculation of 102 CFU/ml or greater of H. cinaedi, while BacT/Alert was negative regardless of the inoculum used (1 to 107 CFU/ml). Another study suggested that the VersaTREK system may perhaps be more sensitive than either the BacT/Alert or Bactec system, with VersaTREK detecting growth of all five H. cinaedi isolates tested within 3 days of incubation, while other systems either needed additional incubation time or did not detect the organism (2). However, this observation has not been studied further. Our laboratory uses the VersaTREK system, and all four aerobic bottles from the patient were positive for growth after a mean of 2.5 days.

Helicobacter cinaedi, as well as a number of other enterohepatic Helicobacter species, can be misidentified as non-jejuni/coli Campylobacter species because of their Gram stain and colony morphologies, as well as by their oxidase-positive, catalase-positive, and urease-negative reactions. Like other Helicobacter species, H. cinaedi will not grow on subculture without use of a microaerobic atmosphere and an extended incubation period. We observed pinpoint growth after 2 days of incubation, with flat, spreading colonies evident after 4 days of incubation. Furthermore, H. cinaedi colonies can appear as a swarming thin film, making it difficult to appreciate growth of the organism (Fig. 2). In the case presented here, only the CVA plate was incubated under microaerobic conditions. However, non-jejuni/coli Campylobacter species and enterohepatic Helicobacter species are unable to grow on this selective medium and/or unable to grow at this increased temperature. Thus, when curved Gram-negative bacilli are observed from a positive blood culture, it would be prudent for laboratories to also include subculture to media incubated under microaerobic conditions at 35 to 37°C.

FIG 2.

Thin film of growth of H. cinaedi on TSA with 5% sheep blood after 4 days of incubation at 35°C under microaerobic conditions.

Neither commercially available biochemical identification systems (e.g., Vitek 2) nor traditional biochemical methods are reliable for the identification of H. cinaedi (2, 3). Identification of H. cinaedi can instead be achieved using 16S rRNA gene sequencing or species-specific PCR (2). The use of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to identify H. cinaedi has not been extensively evaluated. H. cinaedi is not included in the FDA-cleared Bruker Biotyper or Vitek MS (bioMérieux) databases as of the time of writing this article, although we identified the isolate to the species level (score of >2.0) with the Bruker Biotyper RUO database. In addition, Taniguchi et al. showed that it is possible to use individual MALDI-TOF profiles to both identify and subtype H. cinaedi (5).

H. cinaedi typically exhibits low MICs to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and tetracycline, while elevated MICs are frequently observed for macrolides and/or quinolones. While there are no published guidelines for the treatment of H. cinaedi infection, the CDC recommends long-term treatment for 2 to 6 weeks (2). Combination therapy is often used and may include erythromycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, a fluoroquinolone, or a penicillin (6). Penicillins, tetracycline, and aminoglycosides tend to be more effective than cephalosporins, erythromycin, or ciprofloxacin (6). Similar to the patient in this case, recurrent bacteremia with H. cinaedi has been seen frequently in patients undergoing treatment with fluoroquinolones. In the case of our patient, ceftriaxone was chosen in addition to doxycycline because of the desire for combination therapy as well as the patient's continued neutropenia.

While the prognosis for H. cinaedi infection is generally favorable, 30 to 60% of patients have recurrent symptoms, and this organism is known to cause recurrent bacteremia (6). The reason for recurrent bacteremia is unknown, although one possibility is that organisms from the gastrointestinal tract may repeatedly translocate into the blood (3). Treatment failure, particularly if quinolones are used alone, may not eradicate H. cinaedi, which could also explain recurrent bacteremia associated with this organism (6).

In summary, clinical microbiology laboratories should be aware of the possibility of both Helicobacter and Campylobacter species when curved, gull-shaped Gram-negative bacilli are detected in blood cultures. Thus, subculture of positive blood culture broth should also include incubation of culture media in a microaerobic environment at 35 to 37°C for up to 5 days. Selective media or incubation at 42°C is neither required nor recommended for recovery of this bacterium. Given the apparent difficulty in recovering this pathogen from blood culture, laboratorians and clinicians alike should be mindful of the potential need for extended culture incubation periods depending on the blood culture system used. Due to the biochemical similarities between Campylobacter species and H. cinaedi, either MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, species-specific PCR, or 16S rRNA gene sequencing may be required for definitive identification.

SELF-ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS

- Which of the following are considered enterohepatic Helicobacter species?

-

A.Helicobacter pylori

-

B.Helicobacter cinaedi

-

C.Helicobacter canis

-

D.B and C

-

A.

- Which of the following is considered unreliable for identification of H. cinaedi?

-

A.16S rRNA gene sequencing

-

B.Biochemical methods

-

C.MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

-

D.Species-specific PCR

-

A.

- Based on published susceptibilities of H. cinaedi, which drug is most likely to have potent activity against this bacterium in vitro?

-

A.Ciprofloxacin

-

B.Levofloxacin

-

C.Tetracycline

-

D.Clarithromycin

-

A.

For answers to the self-assessment questions and take-home points, see page 347 in this issue (https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02935-15).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee SA, Plett SK, Luetkemeyer AF, Borgo GM, Ohliger MA, Conrad MB, Cookson BT, Sengupta DJ, Koehler JE. 2015. Bartonella quintana aortitis in a man with AIDS, diagnosed by needle biopsy and 16S rRNA gene amplification. J Clin Microbiol 53:2773–2776. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02888-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawamura Y, Tomida J, Morita Y, Fujii S, Okamoto T, Akaike T. 2014. Clinical and bacteriological characteristics of Helicobacter cinaedi infection. J Infect Chemother 20:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araoka H, Baba M, Kimura M, Abe M, Inagawa H, Yoneyama A. 2014. Clinical characteristics of bacteremia caused by Helicobacter cinaedi and time required for blood cultures to become positive. J Clin Microbiol 52:1519–1522. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00265-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyake N, Chong Y, Nishida R, Nagasaki Y, Kibe Y, Kiyosuke M, Shimomura T, Shimono S, Akashi K. 2015. A dramatic increase in the positive blood culture rates of Helicobacter cinaedi: the evidence of differential detection abilities between the Bactec and BacT/Alert systems. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 83:232–233. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taniguchi T, Sekiya A, Higa M, Saeki Y, Umeki K, Okayama A, Hayashi T, Misawa N. 2014. Rapid identification and subtyping of Helicobacter cinaedi strains by intact-cell mass spectrometry profiling with the use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol 52:95–102. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01798-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uçkay I, Garbino J, Dietrich PY, Ninet B, Rohner P, Jacomo V. 2006. Recurrent bacteremia with Helicobacter cinaedi: case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 6:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]