Abstract

A number of studies have investigated the role of serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in patients with Ewing's sarcoma, although these have yielded inconsistent and inconclusive results. Therefore, the present study aimed to systematically review the published studies and conduct a meta-analysis to assess its prognostic value more precisely. Cohort studies assessing the prognostic role of LDH levels in patients with Ewing's sarcoma were included. A pooled hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of overall survival (OS) or 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) was used to assess the prognostic role of the levels of serum LDH. Nine studies published between 1980 and 2014, with a total of 1,412 patients with Ewing's sarcoma, were included. Six studies, with a total of 644 patients, used OS as the primary endpoint and four studies, with 795 patients, used 5-year DFS. Overall, the pooled HR evaluating high LDH levels was 2.90 (95% CI: 2.09–4.04) for OS and 2.40 (95% CI: 1.93–2.98) for 5-year DFS. This meta-analysis demonstrates that high levels of serum LDH are associated with lower OS and 5-year DFS rates in patients with Ewing's sarcoma. Therefore, serum LDH levels are an effective biomarker of Ewing's sarcoma prognosis.

Keywords: lactate dehydrogenase, Ewing's sarcoma, prognosis, meta-analysis

Introduction

Ewing's sarcoma (EWS) is a highly malignant small round-cell tumor arising primarily from bone tissue, but which occasionally occurs in soft tissue. It is the second most common malignant bone tumor in children. With multimodality treatment, the 5-year survival rate for non-metastatic EWS is approximately 60–75%, depending on various factors (1,2). However, the 5-year survival rate for metastatic disease at diagnosis is <30% (3), and for recurrent or refractory disease it falls <20% (4). The prognosis remains dismal for metastasis or chemotherapy resistance. Therefore, there is an urgent requirement for markers to identify which EWS patients have a poor prognosis at the time of diagnosis, so that novel treatments may be initiated earlier in an effort to improve the survival rate.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a tetrameric enzyme that, along with the coenzyme, NAD+, catalyzes the interconversion of lactate and pyruvate. LDH is known to reflect tumor burden (5), and prognostic significance has been demonstrated in several tumor types, including lung (6), pancreatic (7) and prostate cancer (8), hematological malignancies (9), as well as in osteosarcoma (10).

Numerous retrospective studies have evaluated whether the levels of serum LDH may be a prognostic factor for survival in patients with EWS. However, the results of these studies are inconclusive. Serum LDH has been proposed as a prognostic factor in EWS in certain studies, although conflicting results still remain (11). It is unknown whether differences in these investigations have been predominantly due to their limited sample size or to genuine heterogeneity. Therefore, in the present study, a meta-analysis was performed of all available studies that associated the levels of serum LDH with the prognosis of EWS patients.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Cohort studies assessing the prognostic significance of serum LDH levels in EWS were searched in the PubMed, Embase and Web of Science databases. The search strategy was based on combinations of the following terms: ‘Lactate Dehydrogenase’ (OR ‘Lactate Dehydrogenases’ OR ‘LDH’) AND ‘Ewing's sarcoma’ (OR ‘Ewing sarcoma’ OR ‘Sarcoma, Ewing’). An upper date limit of October 10, 2015, was applied. Only studies published in English were included, and unpublished reports were considered. Studies eligible for inclusion in the present meta-analysis conformed with the following criteria: i) A prospective or retrospective cohort study, or randomized controlled trial; ii) tumors has been histologically confirmed as EWS; iii) the studies had examined the association between serum LDH levels and clinical outcome; and iv) the studies had provided sufficient information to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of overall survival (OS) or 5-year disease-free survival (DFS). When the identical authors had reported two or more publications on possibly the same patient populations, only the most recent or most complete study was included in this meta-analysis. Qing Yang and Zhuoying Wang performed the study selection, Suoyuan Li checking the other's work.

The present study was approved by the institutional review board of Shanghai General Hospital (Shanghai. China), and it conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data extraction

Each paper was analyzed for extraction of the relevant data, including first author, publication year, country of the patients, age and gender of the patients, the number of cases, site of the primary tumor and follow-up time. The cutoff of a high level of LDH was also extracted. When the studies involved time-to-event data, the most appropriate statistics to use were log hazard ratio (logHR) and its variance; however, these were not always stated explicitly in each study. Thus, the logHR and standard error of each study were obtained through the following methods: i) Directly extracting the unadjusted HR and 95% CI from each article; ii) estimating HR using the log-rank test, P-values, total events, high level and control group figures (12); and iii) estimating HR using data from the Kaplan-Meier survival curves read by the Engauge Digitizer software (http://markummitchell.github.io/engauge-digitizer/), as well as the minimal and maximal follow-up times (13). Again, Qing Yang and Zhuoying Wang performed the study selection, Suoyuan Li checking the other's work.

Quality assessment

The quality of each included study was assessed by two independent reviewers using the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOQAS) (14). These scales were used to allocate a maximum of nine points for the quality of selection, exposure, comparability and outcome of study participants.

Statistical analysis

HR with 95% CI was used to assess the prognostic role of LDH expression. A heterogeneity test, with inconsistency index (I2) and Q statistical values, was performed. The random effects model was used when significant heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I2 >50%). The fixed-effects model was used for the analysis when there no significant heterogeneity was observed across the included studies (I2 ≤50%) (15). According to the convention, an observed HR >1 implies worse survival rates for the group with high LDH levels. If the 95% CI did not overlap with 1, the impact of LDH on the survival rate was considered to be statistically significant. To validate the credibility of outcomes in the present meta-analysis, sensitivity analysis was performed by the sequential omission of individual studies. The possibility of publication bias was evaluated by visually assessing the symmetry of Begg's funnel plots and Egger's test, where P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant value (16). Statistical analyses were performed using the software STATA version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A two-tailed value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant value.

Results

Study characteristics and quality assessment

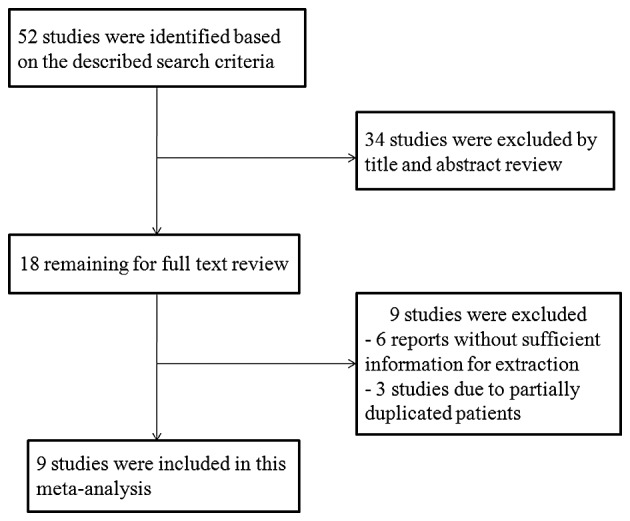

By searching the PubMed, Embase and Web of Science databases, a total of 52 studies were initially identified. Fig. 1 shows a flow diagram of the selection process for defining the relative studies. Following the process of selection, nine studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (17–25). The major characteristics of the nine eligible publications are shown in Table I. These studies were performed in seven countries and published between 1980 and 2014. The total number of patients included the present meta-analysis was 1,412, ranging from 27 to 596 patients per study (median, 157). Six studies with a total of 644 patients used OS as the primary endpoint, whereas four studies with a total of 795 patients used 5-year DFS (one study contained data for OS and 5-year DFS). Quality assessments revealed average NOQAS scores from the two reviewers of 7.0 and 7.5, indicating that all nine eligible studies were of moderate quality.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram to illustrate the study selection procedure.

Table I.

Main characteristics and results of the eligible studies.

| Study, year | Country | No. of patients (M/F)a | Age (years) (< >) | Site of primary tumor (no. of patients) | LDH cutoff (IU/l) (< >)b | HR estimation (OS or 5 year DFS) | P-value | Follow-up (months) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luksch et al, 1999 | Italy | 73 (48/25) | 12 (33/40) | Osseous (73) | 460 (29/35) | 1.76 (0.91–3.41) (OS) | 0.0915 | 35 | (24) |

| Da Costa et al, 2003 | Brazil | 105 (54/51) | 10 | Extremity/axile (57/48) | 370 (56/16) | 2.20 (1.43–6.26) (OS) | 0.003 | 75 | (20) |

| Biswas et al, 2014 | India | 60 (42/18) | 15 (29/31) | Head and neck, chest, limb/spine and pelvis, abdomen (37/23) | NA (25/18) | 5.98 (1.19–30.08) (OS) | 0.03 | 80 | (19) |

| Leavey et al, 2008 | USA | 262 (159/103) | <9 (55) 10–17 (155) ≥18 (52) | Extremity/pelvic/skeletal (56/46/40) | 250 (86/161) | 1.40 (1.05–1.86) (OS) | 0.02 | 96 | (23) |

| Glaubiger et al, 1980 | USA | 117 (NA) | NA | Distal/proxima1/central (30/20/24) | 200 (45/31) | 3.97 (1.98–7.94) (OS) | <0.0001 | 105 | (22) |

| Tural et al, 2012 | Turkey | 27 (18/9) | 23 (range 17–54) | Extremity/axile (11/16) | 240 (10/8) | 5.07 (1.47–17.43) (OS) | 0.01 (OS) | 76 | (25) |

| 4.76 (1.27–17.73) (DFS) | 0.02 (DFS) | ||||||||

| Bacci et al, 2006 | Italy | 596 (379/217) | 13 (264/332) | Extremity/axile (375/221) | 460 (371/193) | 2.20 (1.76–2.87) (DFS) | 0.0005 | 180 | (18) |

| Farley et al, 1987 | England | 56 (NA) | NA | NA | 230 (32/13) | 2.40 (1.15–5.01) (DFS) | 0.003 | 48 | (21) |

| Aparicio et al, 1998 | Spain | 116 (82/34) | 14 (range 1–34) | Extremity/axile/extraosseous (71/34/11) | 300 (61/29) | 4.00 (1.99–8.06) (DFS) | <0.0001 | 128 | (17) |

M/F, the number of males/females.

< > signifies the total no. of patients with an LDH lower than the LDH cutoff/total no. of patients with an LDH higher than the LDH cutoff. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; IU, international units; OS, overall survival; DFS, diseasefree survival; NA, not available; HR, hazard ratio.

Meta-analysis

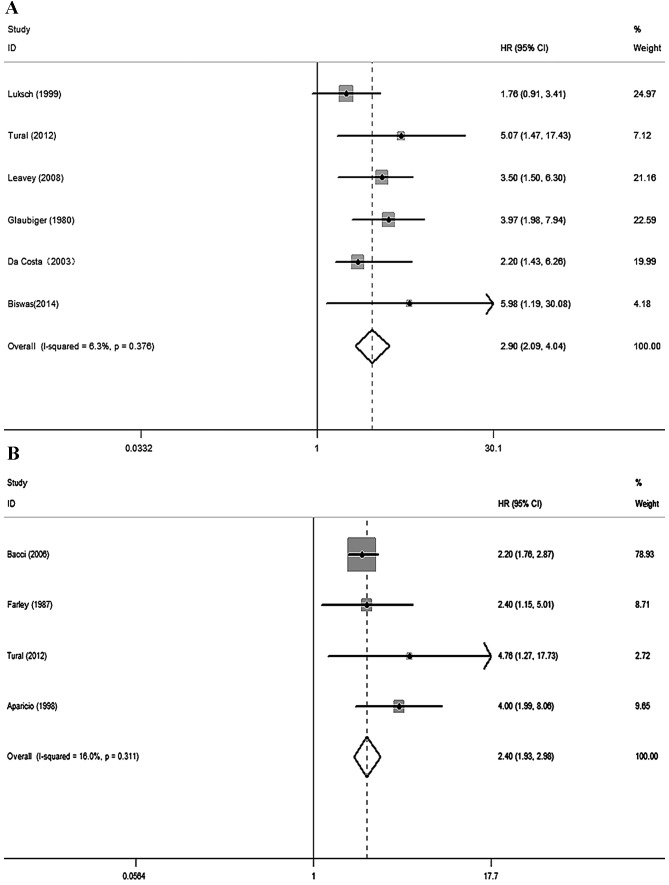

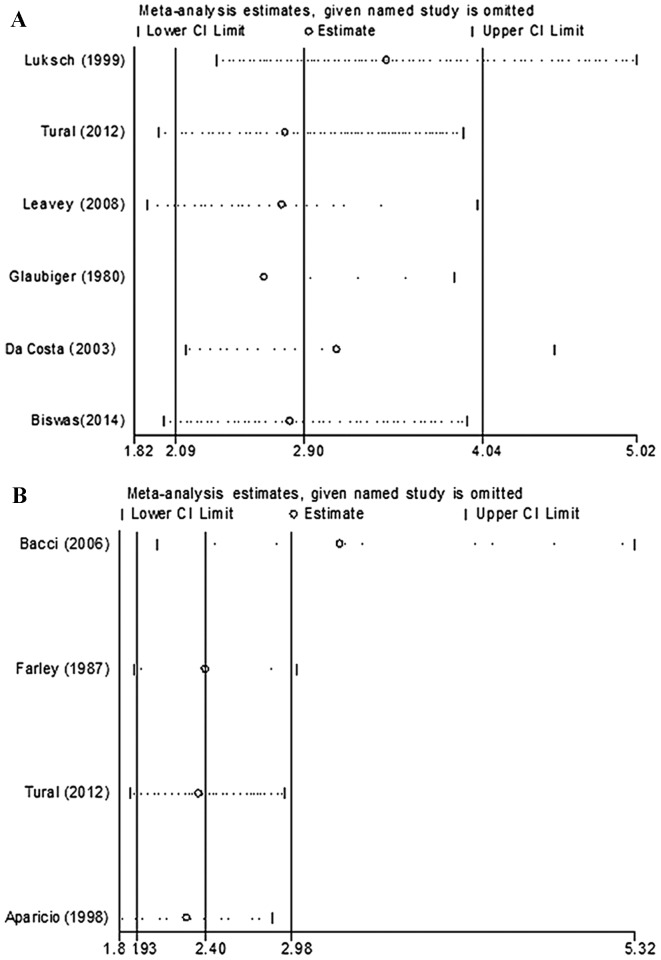

No significant heterogeneity existed across the OS (I2=6.3%, P=0.376) or the 5-year DFS (I2=16.0%, P=0.311) studies; therefore, the fixed effect model was used. Overall, elevated levels of LDH expression were associated with poor prognosis in patients with EWS during the follow-up (OS studies: HR=2.90, 95% CI 2.09–4.04, P<0.001; 5-year DFS studies: HR=2.40, 95% CI 1.93–2.98, P<0.001) (Fig. 2). Sensitivity analysis suggested that the pooled HR was stable, and omitting a single study did not change the significance of the pooled HR (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot analyses. Forest plots of the meta-analysis of the (A) overall survival and (B) 5-year disease free survival of high serum LDH levels in patients with Ewing's sarcoma. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis. Forest plots for the sensitivity analysis in the meta-analysis of (A) the overall survival and (B) the 5-year disease free survival of high serum LDH levels in patients with Ewing's sarcoma. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

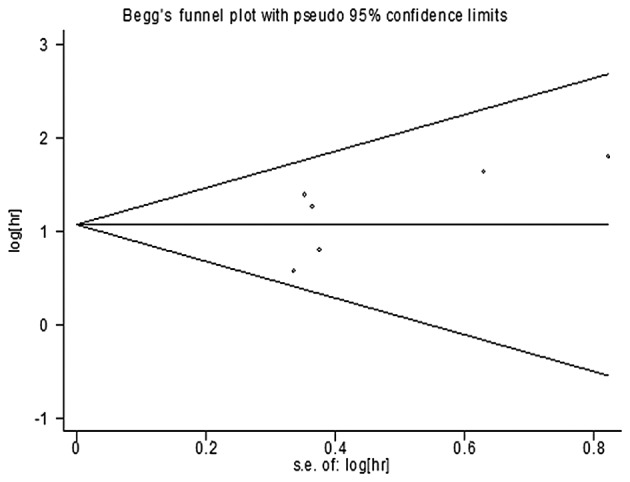

Publication bias

The assessment of publication bias in the selected literature was performed using Begg's test and Egger's test (19,20,22–25). The funnel plot for this meta-analysis revealed evidence of symmetry, and the P-value from the Egger's test was 0.707 in the OS studies (Fig. 4). Thus, there was no significant publication bias risk in the meta-analysis.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of the meta-analysis of the overall survival. hr, hazard ratio; s.e., standard error.

Discussion

Numerous studies have investigated a possible relationship between high serum LDH levels and poor prognosis of patients with EWS, although they have yielded inconsistent and inconclusive results. Meta-analysis is a quantitative approach that integrates all possible studies of an identical topic, and it has been applied to evaluate cancer prognostic markers. Therefore, the present study aimed to systematically review the published studies, and consequently a meta-analysis was performed to assess the prognostic value of high levels of serum LDH more precisely.

Overall, the present meta-analysis combined nine studies including 1,412 patients to yield statistics, indicating that high serum levels of LDH correlate with poor OS and 5-year DFS in patients with EWS during the follow-up. Therefore, our meta-analysis suggests that EWS patients with high serum levels of LDH have a poorer prognosis compared with those with normal serum LDH levels. The findings from our data are conducive for obtaining a more accurate estimate of the prognostic role of the level of serum LDH in patients with EWS.

In recent years, meta-analyses have demonstrated significant associations between various biomarkers and prognosis in patients with tumors. Similarly, several prognosis biomarkers for EWS have been identified, including six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 1 (STEAP1) (26), baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis repeat-containing 5 (BIRC5) (27), nucleophosmin (NPM) (28), CXC-chemokine ligand (CXCL) 16 (29), CXC-chemokine receptor (CXCR) 6 (29), and so forth (30). LDH is released from various organs and tissues when cells are attacked by neoplasms. The first evidence of the prognostic value of LDH levels on prognosis was published in 1975, when Brereton et al (31) and Pomeroy et al (32) demonstrated that the pretreatment pathological level of LDH enabled predictions of the development of metachronous metastases in patients with localized EWS to be made. Recently, Crane et al (33) demonstrated that elevated levels of LDH induced natural killer group 2, member D (NKG2D) ligands on myeloid cells, thereby subverting antitumor immune responses.

The results of the present meta-analysis appear to be fairly robust. On the one hand, the sensitivity analysis suggested that the pooled HR is stable, and omitting a single study did not change the significance of the pooled HR. On the other hand, the regression analysis described by the Egger's test and the funnel plots did not suggest the presence of substantial publication bias. Conversely, several limitations of this meta-analysis are acknowledged. First, the included studies were restricted to studies published in English, and so several published studies in other languages that may have been eligible may have been missed. Secondly, several relevant unpublished studies that could have met the inclusion criteria may have been missed, since only published studies were included. Thirdly, there were only nine published studies with a total of 1,412 EWS patients in our meta-analysis. Such a modestly sized sample of studies may have increased the risk of bias in the present meta-analysis., Well-designed prospective studies, multivariate risk factor analyses, standardized assessment of prognostic markers and using larger sample sizes would help to further explore the association between high serum levels of LDH and the survival of patients with EWS.

In conclusion, high serum levels of LDH are associated with low OS and 5-year DFS rates in patients with EWS, and therefore it is an effective biomarker for the assessment of patient prognosis. These findings may allow physicians to more precisely identify patients with EWS who have a higher risk of relapse or metastatic spread, and to prescribe more appropriate therapies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NSFC (no. 81202115), the Key Project of Basic Research of Shanghai (no. 11JC1410101), the Innovative Frontier Technology Program of Shenkang (no. SHDC12013107) and the Excellent Young Talent Program of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (no. XYQ2013108).

References

- 1.Rodríguez-Galindo C, Liu T, Krasin MJ, Wu J, Billups CA, Daw NC, Spunt SL, Rao BN, Santana VM, Navid F. Analysis of prognostic factors in ewing sarcoma family of tumors: Review of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital studies. Cancer. 2007;110:375–384. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granowetter L, Womer R, Devidas M, Krailo M, Wang C, Bernstein M, Marina N, Leavey P, Gebhardt M, Healey J, et al. Dose-intensified compared with standard chemotherapy for nonmetastatic Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: A Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2536–2541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolb EA, Kushner BH, Gorlick R, Laverdiere C, Healey JH, LaQuaglia MP, Huvos AG, Qin J, Vu HT, Wexler L, et al. Long-term event-free survival after intensive chemotherapy for Ewing's family of tumors in children and young adults. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3423–3430. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker LM, Pendergrass TW, Sanders JE, Hawkins DS. Survival after recurrence of Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4354–4362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walenta S, Mueller-Klieser WF. Lactate: Mirror and motor of tumor malignancy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2004;14:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albain KS, Crowley JJ, LeBlanc M, Livingston RB. Determinants of improved outcome in small-cell lung cancer: An analysis of the 2,580-patient Southwest Oncology Group data base. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1563–1574. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.9.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tas F, Aykan F, Alici S, Kaytan E, Aydiner A, Topuz E. Prognostic factors in pancreatic carcinoma: Serum LDH levels predict survival in metastatic disease. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24:547–550. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smaletz O, Scher HI, Small EJ, Verbel DA, McMillan A, Regan K, Kelly WK, Kattan MW. Nomogram for overall survival of patients with progressive metastatic prostate cancer after castration. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3972–3982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terpos E, Katodritou E, Roussou M, Pouli A, Michalis E, Delimpasi S, Parcharidou A, Kartasis Z, Zomas A, Symeonidis A, et al. High serum lactate dehydrogenase adds prognostic value to the international myeloma staging system even in the era of novel agents. Eur J Haematol. 2010;85:114–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Sun MX, Hua YQ, Cai ZD. Prognostic significance of serum lactate dehydrogenase level in osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:1205–1210. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1644-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casadei R, Magnani M, Biagini R, Mercuri M. Prognostic factors in Ewing's sarcoma of the foot. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:230–238. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200403000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815–2834. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::AID-SIM110>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger M, Smith G Davey, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aparicio J, Munárriz B, Pastor M, Vera FJ, Castel V, Aparisi F, Montalar J, Badal MD, Gómez-Codina J, Herranz C. Long-term follow-up and prognostic factors in Ewing's sarcoma. A multivariate analysis of 116 patients from a single institution. Oncology. 1998;55:20–26. doi: 10.1159/000011841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacci G, Longhi A, Ferrari S, Mercuri M, Versari M, Bertoni F. Prognostic factors in non-metastatic Ewing's sarcoma tumor of bone: An analysis of 579 patients treated at a single institution with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy between 1972 and 1998. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:469–475. doi: 10.1080/02841860500519760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biswas B, Shukla NK, Deo SV, Agarwala S, Sharma DN, Vishnubhatla S, Bakhshi S. Evaluation of outcome and prognostic factors in extraosseous Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1925–1931. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.da Costa CM, Lopes A, de Camargo B. A simple cost-effective lactate dehydrogenase level measurement can stratify patients with Ewing's tumor into low and high risk. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:656. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farley FA, Healey JH, Caparros-Sison B, Godbold J, Lane JM, Glasser DB. Lactase dehydrogenase as a tumor marker for recurrent disease in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer. 1987;59:1245–1248. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870401)59:7<1245::AID-CNCR2820590702>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glaubiger DL, Makuch R, Schwarz J, Levine AS, Johnson RE. Determination of prognostic factors and their influence on therapeutic results in patients with Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer. 1980;45:2213–2219. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800415)45:8<2213::AID-CNCR2820450834>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leavey PJ, Mascarenhas L, Marina N, Chen Z, Krailo M, Miser J, Brown K, Tarbell N, Bernstein ML, Granowetter L, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with Ewing sarcoma (EWS) at first recurrence following multi-modality therapy: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:334–338. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luksch R, Sampietro G, Collini P, Boracchi P, Massimino M, Lombardi F, Gandola L, Giardini R, Fossati-Bellani F, Migliorini L, et al. Prognostic value of clinicopathologic characteristics including neuroectodermal differentiation in osseous Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors in children. Tumori. 1999;85:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tural D, Mandel N Molinas, Dervisoglu S, Dincbas F Oner, Koca S, Oksuz D Colpan, Kantarci F, Turna H, Selcukbiricik F, Hiz M. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors in adults: Prognostic factors and clinical outcome. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:420–426. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grunewald TG, Ranft A, Esposito I, da Silva-Buttkus P, Aichler M, Baumhoer D, Schaefer KL, Ottaviano L, Poremba C, Jundt G, et al. High STEAP1 expression is associated with improved outcome of Ewing's sarcoma patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2185–2190. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hingorani P, Dickman P, Garcia-Filion P, White-Collins A, Kolb EA, Azorsa DO. BIRC5 expression is a poor prognostic marker in Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:35–40. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haga A, Ogawara Y, Kubota D, Kitabayashi I, Murakami Y, Kondo T. Interactomic approach for evaluating nucleophosmin-binding proteins as biomarkers for Ewing's sarcoma. Electrophoresis. 2013;34:1670–1678. doi: 10.1002/elps.201200661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Na KY, Kim HS, Jung WW, Sung JY, Kalil RK, Kim YW, Park YK. CXCL16 and CXCR6 in Ewing sarcoma family tumor. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shukla N, Schiffman J, Reed D, Davis IJ, Womer RB, Lessnick SL, Lawlor ER. COG Ewing Sarcoma Biology Committee: Biomarkers in Ewing Sarcoma: The promise and challenge of personalized medicine. A Report from the Children's Oncology Group. Front Oncol. 2013;3:141. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brereton HD, Simon R, Pomeroy TC. Pretreatment serum lactate dehydrogenase predicting metastatic spread in Ewing's sarcoma. Ann Intern Med. 1975;83:352–354. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-83-3-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pomeroy TC, Johnson RE. Combined modality therapy of Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;35:36–47. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197501)35:1<36::AID-CNCR2820350106>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crane CA, Austgen K, Haberthur K, Hofmann C, Moyes KW, Avanesyan L, Fong L, Campbell MJ, Cooper S, Oakes SA, et al. Immune evasion mediated by tumor-derived lactate dehydrogenase induction of NKG2D ligands on myeloid cells in glioblastoma patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:12823–12828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413933111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]