Abstract

We previously reported that mRNA expression of the unique alternatively spliced OPRM1 isoform μ-opioid receptor-1K (MOR-1K), which exhibits excitatory cellular signaling, is elevated in HIV-infected individuals with combined neurocognitive impairment (NCI) and HIV encephalitis (HIVE). It has recently been shown that the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) chaperones MOR-1K, normally localized intracellularly, to the cell surface. Here, we found mRNA expression of the adrenoceptor beta 2 (ADRB2) gene is also elevated in NCI-HIVE individuals, as well as that β2-AR protein expression is elevated in HIV-1-infected primary human astrocytes treated with morphine, and discuss the implications for MOR-1K subcellular localization in this condition.

Keywords: β-Adrenergic receptor, μ-Opioid receptor, Splice variant, Central nervous system, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders, HIV encephalitis

Introduction

While numerous splice variants of the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) have been identified (reviewed in (Pan 2005)), a 6-transmembrane isoform of MOR, termed MOR-1K, has also been discovered (Shabalina et al. 2009). The characterization of MOR-1K has revealed unique properties compared to the 7-transmembrane canonical MOR-1 such as excitatory cellular signaling with morphine stimulation and that the truncated receptor is mainly localized to intracellular compartments (Convertino et al. 2015; Gris et al. 2010).

As excitatory cellular signaling by opiates such as morphine could be a mechanism underlying opiate-driven enhanced HIV-related neuropathogenesis (El-Hage et al. 2005; Gurwell et al. 2001; Hauser et al. 2012), we previously examined MOR-1K mRNA expression levels in brain tissue from groups of HIV-infected individuals with varying levels of neurocognitive impairment (NCI) ± HIV encephalitis (HIVE) (Dever et al. 2014), many of which had a history of polysubstance use including opiates (Dever et al. 2015, 2012). We found MOR-1K mRNA was significantly elevated in the group of individuals that were most severely impaired with combined NCI-HIVE. Furthermore, in this same study, networking analysis revealed the product of the FLNA gene, filamin A, as a potential interacting protein with MOR in the NCI-HIVE condition, and we found FLNA mRNA expression levels were also significantly elevated in these individuals as well as that filamin A expression trafficked MOR-1K to the cell surface in vitro.

Although the consequences of MOR-1K cell surface localization were not known at the time our study was published, a recent report has shown expression of the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR), but not β1-AR or β3-AR, also chaperones MOR-1K to the plasma membrane and that the MOR-1K/β2-AR heterodimer mediates the excitatory cellular signaling effects of this MOR variant (Samoshkin et al. 2015). The purpose of the current study was therefore to expand on the findings of Samoshkin et al. by examining expression of the β1–3-AR genes in the context of HIV infection. Elevated levels specifically of the β2-AR subtype may be another mechanism that could result in MOR-1K trafficking to the surface of cells in NCI-HIVE individuals and lead to enhanced neuropathogenesis in this condition from opiate exposure.

Materials and methods

Human brain tissue

Human brain tissue was obtained from a subset of samples used in the National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium (NNTC) Gene Array Project (Gelman et al. 2012; Morgello et al. 2001). Briefly, individuals examined were either HIV-negative (n = 6) or HIV-positive with combined neurocognitive impairment (NCI) and HIV encephalitis (HIVE) (n = 5) with post-mortem tissue taken from the frontal lobe white matter and/or frontal cortex. Details on the individual samples analyzed for each group in this study have been described previously (Dever et al. 2014, 2015, 2012).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA, USA) and used to generate cDNA templates by reverse transcription of 1 μg RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems; Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 μL containing SensiMix SYBR qPCR reagents (Bioline; Taunton, MA, USA) using a Corbett Rotor-Gene 6000 real-time PCR system (Qiagen). PCR conditions consisted of an initial hold step at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 amplification cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. Sequences of the primer sets used were forward: 5′-CGGGAACAGGAACACACTAC-3′ and reverse: 5′-TTTGCCCTACACAAGGAAAG-3′ for ADRB1; forward: 5′-GAGCACAAAGCCCTCAAGAC-3′ and reverse: 5′-TGGAAGGCAATCCTGAAATC-3′ for ADRB2; forward: 5′-ACCATCCTCTTGCTCTCTGT-3′ and reverse: 5′-AGCCTGGAGAACACTAAGGT-3′ for ADRB3; and forward: 5′-GCTGCGGTAATCATGAGGATAAGA-3′ and reverse: 5′-TGAGCACAAGGCCTTCTAACCTTA-3′ for TATA-binding protein (TBP). The specificity of the amplified products was verified by melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. qRT-PCR data were calculated as relative expression levels by normalization to TBP mRNA using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

HIV-1 infection and treatment of astrocytes

Primary human brain astrocytes were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA, USA) and cultured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells grown to ~75–80 % confluency were infected with the CCR5-tropic HIV-1 SF162 strain (obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: HIV-1 SF162 Virus from Dr. Jay Levy (Cheng-Mayer and Levy 1988)) at a concentration of 1 ng HIV-1 p24/106 cells and cultured for 7 days in the presence or absence of 1 μM morphine sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO, USA).

Western blotting

Whole cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer supplemented with a mixture of protease and phosphatase inhibitors and separated by SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting. Primary antibodies used were β2-AR (R11E1) at a 1:100 dilution and β-actin (C4) at a 1:200 dilution, both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). The addition of each primary antibody was followed by incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling Technology; Danvers, MA, USA) used at a 1:1000 dilution. Immunoblots were exposed to SuperSignal West Femto Substrate (Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) and visualized using a ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories; Hercules, CA, USA). Protein band intensity was quantified with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health (NIH); Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistics

Student’s unpaired, two-tailed t tests for paired data and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test for multiple comparisons were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software; La Jolla, CA, USA). A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

mRNA expression of β-AR genes in NCI-HIVE individuals

To determine whether the expression of β-AR genes might differ in a manner where corresponding protein increases could affect MOR-1K subcellular localization in the context of HIV infection, mRNA expression levels of the adrenoceptor beta (ADRB) genes ADRB1, ADRB2, and ADRB3 were examined between uninfected and HIV-infected individuals with combined NCI-HIVE using qRT-PCR. NCI-HIVE individuals were chosen for this analysis as we previously showed that expression of MOR-1K mRNA was significantly elevated in this condition compared to other groups of HIV-infected individuals with varying levels of NCI (Dever et al. 2014). Interestingly, out of ADRB1, ADRB2, and ADRB3 expression, only ADRB2 mRNA was found to be significantly elevated in NCI-HIVE compared to uninfected individuals (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ADRB2, but not ADRB1 or ADRB3, mRNA expression levels are elevated in HIV-infected individuals with combined neurocognitive impairment (NCI) and HIV encephalitis (HIVE). Expression of the indicated genes was measured by qRT-PCR for the indicated groups of individuals. Data are presented relative to HIV-negative individuals which were set to a value of 1. p = 0.1295 for ADRB1, p = 0.0264 for ADRB2, and p = 0.1298 for ADRB3 when HIV-negative and HIV-positive/NCI-HIVE groups were compared. *p < 0.05. Error bars show the SEM

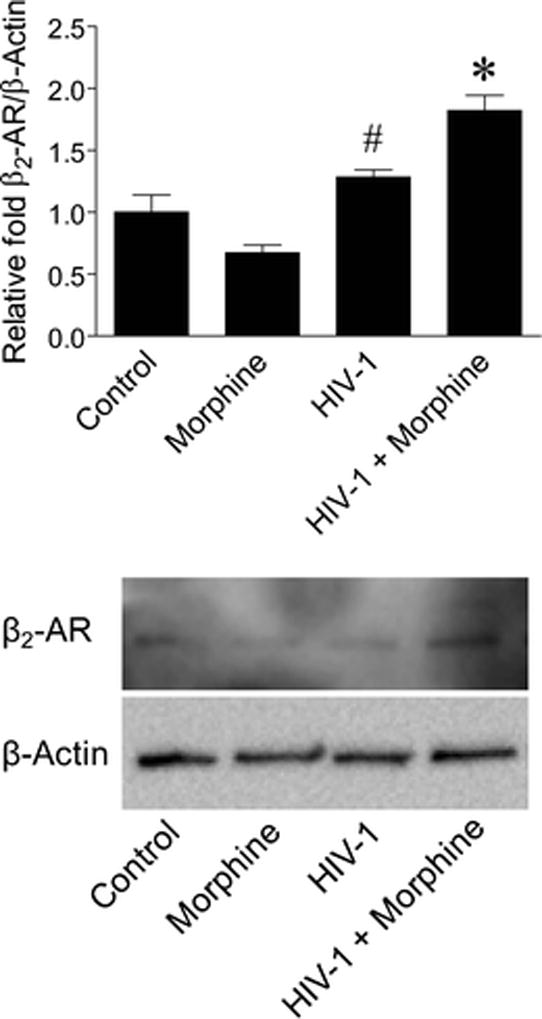

β2-AR protein expression in astrocytes following HIV-1 infection and morphine treatment

We previously profiled for the presence of MOR-1K mRNA across various primary human central nervous system cell types and detected expression in astrocytes, but not microglia and neurons (Dever et al. 2014). To determine whether HIV-opiate drug interactions might affect MOR-1K subcellular localization in astrocytes, β2-AR protein expression levels were examined by western blotting analysis in this cell type after HIV-1 infection ± morphine treatment. Although β2-AR protein expression was significantly higher with HIV-1 infection compared to morphine treatment alone, the combined effect resulted in significantly elevated expression levels compared to all other groups of cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

β2-AR protein expression levels are elevated in HIV-1-infected primary human astrocytes with combined morphine treatment. Expression of β2-AR was detected by western blotting analysis for the indicated groups of cells. β-Actin was used as a normalization control. Data are presented relative to control cells which were set to a value of 1. F(3,4) = 22.53, p = 0.0057. #p < 0.05 when compared to morphine treatment and *p < 0.05 when compared to all other groups. Error bars show the SEM for two independent experiments. Representative blots are shown

Discussion

While the functional activity of MOR-1K may have been previously questioned due to its intracellular localization, it is now clear that this receptor can translocate to the cell surface by interactions with at least two different proteins, filamin A and β2-AR (Dever et al. 2014; Samoshkin et al. 2015). However, it appears that the heterodimerization of MOR-1K specifically with β2-AR, but not β1-AR or β3-AR, is the primary interaction responsible for mediating the excitatory cellular signaling effects this MOR variant exhibits upon opiate stimulation (Samoshkin et al. 2015). The complementary data presented in this study showing ADRB2, but not ADRB1 or ADRB3, mRNA expression levels are significantly elevated in NCI-HIVE individuals, along with simultaneous significant elevations in MOR-1K mRNA (Dever et al. 2014), suggests that in this condition corresponding β2-AR/MOR-1K protein increases could maximize trafficking of MOR-1K to the surface of cells in a manner which promotes its excitatory signaling activity in the presence of opiates. Therefore, our findings present a potential mechanism by which opiate exposure in NCI-HIVE individuals may trigger cellular signaling events that could lead to enhanced neuropathogenesis from HIV-opiate drug interactions (reviewed in (Hauser et al. 2012)). Furthermore, our results showing elevated levels of β2-AR protein expression in HIV-1-infected astrocytes with combined morphine treatment point to a cell type where these interactions via this mechanism may be of particular importance. As we were unable to perform other assays with human brain tissue due to the limited amounts available, future studies will be needed to confirm our findings with mRNA expression at the protein level by western blotting and immunohistochemical analyses, preferably using samples from uninfected and NCI-HIVE individuals with clear histories of opiate use/non-use.

Apart from β2-AR, the function of cell surface-localized MOR-1K in cellular signaling and non-canonical processes involving MOR such as HIV cellular binding and entry with chemokine receptors is an area needing future investigation. For example, MOR can form heterodimers and undergo cross-desensitization with the chemokine HIV co-receptor CCR5 (Chen et al. 2004), and we previously showed that the action of the CCR5-mediated viral entry inhibitor maraviroc was attenuated by morphine in a MOR-dependent manner (El-Hage et al. 2013). Therefore, given that the subcellular localization of MOR-1K appears not to be constitutive but mediated by the expression of interacting proteins, this isoform could uniquely affect cellular signaling and viral entry processes in a regulated manner compared to other MOR variants.

In conclusion, our past and present findings suggest that in NCI-HIVE individuals, elevated levels of mRNAs encoding proteins known to interact with MOR-1K could lead to localization of this receptor on the surface of cells by multiple protein-protein interactions. In addition, as β2-AR can chaper-one other G-protein-coupled receptors such as the CB1 cannabinoid and M71 olfactory receptors (Hague et al. 2004; Hudson et al. 2010), the results presented here have broader implications in that the cell surface complement of receptors may be dramatically altered in NCI-HIVE individuals which could negatively impact this condition in response to certain stimuli.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kurt F. Hauser for use of the human tissue samples that were analyzed in this study as well as for use of laboratory space and equipment from which part of the data were generated. We are also most grateful to the individuals who donated the tissue. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grants F32 DA033898 to S.M.D. and R01 DA036154 to N.E.H. The human tissue provided by the National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium (NNTC) for this publication was made possible from NIH funding through the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) by the following grants: Manhattan HIV Brain Bank: U01 MH083501, R24 MH59724; Texas NeuroAIDS Research Center: U01 MH083507, R24 NS45491; National Neurological AIDS Bank: 5U01 MH083500, NS38841; California NeuroAIDS Tissue Network: U01 MH083506, R24 MH59745; and Statistics and Data Coordinating Center: U01 MH083545, N01 MH32002. This publication’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the NNTC or endorsement by any other individuals.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen C, Li J, Bot G, Szabo I, Rogers TJ, Liu-Chen LY. Heterodimerization and cross-desensitization between the mu-opioid receptor and the chemokine CCR5 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;483:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng-Mayer C, Levy JA. Distinct biological and serological properties of human immunodeficiency viruses from the brain. Ann Neurol. 1988;23(Suppl):S58–S61. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convertino M, Samoshkin A, Viet CT, Gauthier J, Li Fraine SP, Sharif-Naeini R, Schmidt BL, Maixner W, Diatchenko L, Dokholyan NV. Differential regulation of 6- and 7-transmembrane helix variants of mu-opioid receptor in response to morphine stimulation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever SM, Costin BN, Xu R, El-Hage N, Balinang J, Samoshkin A, O’Brien MA, McRae M, Diatchenko L, Knapp PE, Hauser KF. Differential expression of the alternatively spliced OPRM1 isoform mu-opioid receptor-1K in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2014;28:19–30. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever SM, Rodriguez M, Lapierre J, Costin BN, El-Hage N. Differing roles of autophagy in HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment and encephalitis with implications for morphine co-exposure. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:653. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever SM, Xu R, Fitting S, Knapp PE, Hauser KF. Differential expression and HIV-1 regulation of mu-opioid receptor splice variants across human central nervous system cell types. J Neurovirol. 2012;18:181–190. doi: 10.1007/s13365-012-0096-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage N, Dever SM, Podhaizer EM, Arnatt CK, Zhang Y, Hauser KF. A novel bivalent HIV-1 entry inhibitor reveals fundamental differences in CCR5-mu-opioid receptor interactions between human astroglia and microglia. AIDS. 2013;27:2181–2190. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283639804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage N, Gurwell JA, Singh IN, Knapp PE, Nath A, Hauser KF. Synergistic increases in intracellular Ca2+, and the release of MCP-1, RANTES, and IL-6 by astrocytes treated with opiates and HIV-1 tat. Glia. 2005;50:91–106. doi: 10.1002/glia.20148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman BB, Chen T, Lisinicchia JG, Soukup VM, Carmical JR, Starkey JM, Masliah E, Commins DL, Brandt D, Grant I, Singer EJ, Levine AJ, Miller J, Winkler JM, Fox HS, Luxon BA, Morgello S. The national NeuroAIDS tissue consortium brain gene array: two types of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gris P, Gauthier J, Cheng P, Gibson DG, Gris D, Laur O, Pierson J, Wentworth S, Nackley AG, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. A novel alternatively spliced isoform of the mu-opioid receptor: functional antagonism. Mol Pain. 2010;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurwell JA, Nath A, Sun Q, Zhang J, Martin KM, Chen Y, Hauser KF. Synergistic neurotoxicity of opioids and human immunodeficiency virus-1 tat protein in striatal neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 2001;102:555–563. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00461-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hague C, Uberti MA, Chen Z, Bush CF, Jones SV, Ressler KJ, Hall RA, Minneman KP. Olfactory receptor surface expression is driven by association with the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13672–13676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403854101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser KF, Fitting S, Dever SM, Podhaizer EM, Knapp PE. Opiate drug use and the pathophysiology of neuroAIDS. Curr HIV Res. 2012;10:435–452. doi: 10.2174/157016212802138779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Hebert TE, Kelly ME. Physical and functional interaction between CB1 cannabinoid receptors and beta2-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:627–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgello S, Gelman BB, Kozlowski PB, Vinters HV, Masliah E, Cornford M, Cavert W, Marra C, Grant I, Singer EJ. The national NeuroAIDS tissue consortium: a new paradigm in brain banking with an emphasis on infectious disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2001;27:326–335. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2001.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan YX. Diversity and complexity of the mu opioid receptor gene: alternative pre-mRNA splicing and promoters. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24:736–750. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoshkin A, Convertino M, Viet CT, Wieskopf JS, Kambur O, Marcovitz J, Patel P, Stone LS, Kalso E, Mogil JS, Schmidt BL, Maixner W, Dokholyan NV, Diatchenko L. Structural and functional interactions between six-transmembrane mu-opioid receptors and beta2-adrenoreceptors modulate opioid signaling. Sci Report. 2015;5:18198. doi: 10.1038/srep18198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalina SA, Zaykin DV, Gris P, Ogurtsov AY, Gauthier J, Shibata K, Tchivileva IE, Belfer I, Mishra B, Kiselycznyk C, Wallace MR, Staud R, Spiridonov NA, Max MB, Goldman D, Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. Expansion of the human mu-opioid receptor gene architecture: novel functional variants. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1037–1051. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]