Abstract

The effects of variations in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK) medium on the infectivity and pathogenicity of Borrelia burgdorferi clinical isolates were assessed by retrospective and prospective studies using a murine model of Lyme borreliosis. Thirty of 35 (86%) mice infected with any of six virulent B. burgdorferi clinical isolates grown in a BSK-H medium developed clinically apparent arthritis. By contrast, arthritis was observed in only 25 of 60 (42%) mice inoculated with two of these B. burgdorferi strains grown in a different lot of BSK-H medium (P < 0.001). In a prospective study, mice inoculated with a B. burgdorferi clinical isolate grown in a BSK medium prepared in-house produced significantly greater disease than those injected with the same isolate cultured in BSK-H medium (P < 0.05). The attenuated pathogenicity is not due to the loss of plasmids during in vitro cultivation. The data suggest that variations in BSK medium have a significant impact on the infectivity and pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi clinical isolates.

Borrelia burgdorferi, the etiologic agent of Lyme borreliosis, was first recovered from Ixodes scapularis ticks (3, 5) by using a modified Kelly medium that was originally developed for growing relapsing-fever spirochetes (11). This modified medium was designated Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK) medium and was subsequently employed to cultivate B. burgdorferi from patients with Lyme borreliosis (4, 25). Modifications of BSK medium have been reported and used routinely to grow B. burgdorferi sensu lato from different biological and geographic sources. These modifications include BSK-II (3), BSK-H (20), and modified Kelly medium (MKM) (21). Virtually all BSK formulations contain N-acetylglucosamine, yeast extract, amino acids, vitamins, nucleotides, and serum, but there is variation in several other chemical components among these alternative formulations of BSK medium (3, 20, 21).

In 1993, a standardized BSK medium designated BSK-H, which contains bovine serum albumin (BSA) and rabbit serum, was described (20). It is commercially available (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and has been utilized widely for recovery of B. burgdorferi in epidemiological and clinical studies and for cultivation of B. burgdorferi isolates for various research purposes.

Previous studies have suggested that both the host factors and the pathogenic properties of virulent spirochetes contribute to the development and severity of Lyme disease (29). In the United States, several distinct genotypes of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto have been cultured from patients with erythema migrans, and these strains and have been found to vary substantially in their ability to disseminate in patients and laboratory animals (13, 27, 28, 31). Therefore, it appears to be essential to assess the pathogenicity of a given B. burgdorferi isolate. Presently, the infectivity and pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi strains can be determined only in laboratory animals (e.g., mice), and they require the prior growth of B. burgdorferi isolates or purified clones in BSK medium.

The recovery rates of B. burgdorferi from vector ticks and skin biopsy samples of patients with early Lyme borreliosis may be affected by the formulation of the BSK medium employed (15, 19). In a 2-year prospective study, Picken et al. demonstrated that cultivation of 758 specimens from the sites of erythema migrans on patients with Lyme borreliosis resulted in a culture positivity rate of 36% for modified Kelly-Pettenkofer medium and 24% for BSK-II medium (P < 0.05) (19). In addition, lot variations in components like BSA or components in the BSK formulation have been shown to have dramatic effects on the growth of B. burgdorferi and on the induction of differential gene expression (6, 33). Moreover, it has been reported that the virulence of the N40 isolate of B. burgdorferi increased following a change in growth medium; this increase in virulence was characterized by a 50-fold decrease in the number of B. burgdorferi isolates required for 50% infection and by an increase in severity of the disease (14). However, the effect of variations in BSK media on the pathogenicity of virulent B. burgdorferi isolates has not been assessed systematically. In this study, retrospective analyses and prospective experiments were carried out to evaluate the impact of variations in BSK media on the infectivity and pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi clinical isolates. A B. burgdorferi isolate or variant is considered to be infectious if it can be recovered by cultivation from tissue specimens of inoculated mice. Such an isolate or variant is further defined as pathogenic if clinically apparent or histologically confirmed arthritic or cardiac disease can be documented in a Lyme borreliosis-susceptible animal model (1).

Retrospective analyses.

Since September 1999, several experiments were carried out with C3H/HeJ mice to assess the infectivity and pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi clinical isolates representing distinct genotypes. All B. burgdorferi clinical isolates examined were grown in BSK-H medium supplemented with 6% rabbit serum (Sigma Chemicals). C3H/HeJ mice were inoculated intradermally with 104 organisms with a low passage number in phosphate-buffered saline buffer as previously reported (27, 28). It was found that B. burgdorferi RST1 clinical isolates are highly pathogenic. All C3H/HeJ mice (35 of 35) inoculated with any of six B. burgdorferi RST1 isolates examined were infected, and 30 of the 35 (86%) infected mice developed clinically apparent joint swelling (27, 28).

However, attenuated infectivity and pathogenicity was observed when two of these pathogenic B. burgdorferi clinical isolates, BL206 and B515, were examined in several subsequent experiments. As summarized in Table 1, all 15 C3H/HeJ mice inoculated with isolates BL206 and B515 grown in a particular lot of Sigma BSK-H medium (BSK-H1) were infected and developed Lyme arthritis. By contrast, only 32 of 60 (53%) mice were infected after inoculation with the same strains grown in a different lot of BSK-H medium (BSK-H2) during the period of May 2001 to November 2002 (15 of 15 versus 32 of 60, P < 0.001, Fisher's exact test). A significant decrease in pathogenicity was also noted when these two strains were grown in BSK-H2 medium. Only 25 of 60 (42%) mice inoculated with either isolate cultured in BSK-H2 medium showed apparent joint swelling compared to those inoculated with either isolate passaged in BSK-H1 medium (15 of 15, P < 0.0001, Fisher's exact test).

TABLE 1.

Retrospective analysis of the infectivities and pathogenicities of B. burgdorferi RST1 clinical isolates after growth in different BSK culture media

| Mediuma | Borrelia isolate | Passageb/ infected-mouse isolate | Infectivityc (%) | Patho- genicityd (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSK H-1 | BL206 | p3 | 10/10 (100) | 10/10 | 27 |

| BL203 | p4 | 5/5 (100) | 1/5 | 28 | |

| BL268 | p2 | 5/5 (100) | 4/5 | 28 | |

| B479 | p4 | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 | 28 | |

| B491 | p4 | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 | 28 | |

| B515 | p4 | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 | 28 | |

| Total | 35/35 (100) | 30/35 (86) | |||

| BSK H-2 | BL206 | p2 | 1/3 (33) | 1/3 (33) | This study |

| p5 | 8/10 (80) | 3/10 (30) | This study | ||

| mp1 | 5/10 (50) | 3/10 (30) | This study | ||

| mp1/E187 | 1/4 (25) | 1/4 (25) | This study | ||

| mp3 | 2/8 (25) | 2/8 (25) | This study | ||

| B515 | p3 | 10/10 (100) | 10/10 (100) | This study | |

| p4 | 3/11 (27) | 3/11 (27) | This study | ||

| mp1/B110 | 2/4 (50) | 2/4 (50) | This study | ||

| Total | 32/60 (53) | 25/60 (42) | |||

| BSK-S | BL206 | mp1/E187 | 2/2 (100) | 2/2 (100) | This study |

| mp4/E187 | 10/10 (100) | 10/10 (100) | This study | ||

| B515 | mp1/B110 | 3/3 (100) | 3/3 (100) | This study | |

| Total | 15/15 (100) | 15/15 (100) |

BSK-H1 and BSK-H2 refer to different lots of BSK-H medium (Sigma); BSK-S is a BSK medium prepared in-house.

The number of times that individual isolates were passaged in BSK medium since their recovery from patients (p followed by a number) or experimentally infected mice (mp followed by a number).

Number of mice infected/number of mice examined between days 14 and 28 postinoculation.

Pathogenicity was determined by measurement of the ankle joint swelling and/or histopathology of one ankle joint for each mouse (histological analysis was performed only for isolates cultured in BSK-H1 medium).

Prospective studies.

In order to examine whether the observed attenuation in pathogenicity is a consequence of growing spirochetes in different lots of BSK-H media, two clinical isolates that had been evaluated in the above-mentioned studies, BL206 and B515, were cultured for one to four passages in a BSK medium prepared in-house (BSK-S) (30) and evaluated for their infectivity and pathogenicity. The differences in formulation between BSK-H and BSK-S media are the final concentration of BSA (50 g per liter in BSK-H versus 26 g per liter in BSK-S), the amount of TC yeastolate (2 g in BSK-H versus 3.54 g in BSK-S), and the type of supplemented rabbit serum (R7136 [Sigma] in BSK-H versus R4505 [Sigma] after heat inactivation at 56°C for 30 min in BSK-S).

In an initial experiment with 15 C3H/HeJ mice, all mice inoculated with isolate BL206 (n = 12) or isolate B515 (n = 3) grown in BSK-S medium were infected and developed apparent arthritis (Table 1). To investigate further the potential effects of variations in BSK media on the infectivity and pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi clinical isolates, prospective experiments were performed. Low-passage-number B. burgdorferi isolates B515 and BL206 were grown in different lots of BSK-H medium (BSK-H2 [lot 120K2369] and BSK-H3 [lot 62K2399]; Sigma) until mid-log phase (∼107 cells/ml). They were then subcultured in parallel by a 1:50 dilution into different lots of BSK-H or BSK-S medium for one to two passages. Spirochetes (104) from each culture were subsequently inoculated intradermally into five to six C3H/HeJ mice. The infectivities of the B. burgdorferi organisms cultured in different BSK media were assessed by culture of spirochetes from ear biopsy specimens, and the severity of arthritis was estimated by caliper measurement of increased ankle joint diameter (27). In addition, multiplex real-time quantitative PCR was employed to determine the spirochete burden in tissues of mice (26) and Western immunoblotting was used to detect B. burgdorferi-specific antibodies as previously described (28).

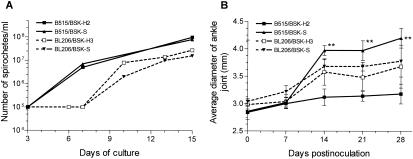

Different growth curves were observed between the two B. burgdorferi isolates when they were grown in either BSK-H or BSK-S medium (Fig. 1A). This is consistent with our previous observation that there is significant variation in the growth kinetics of individual, low-passage-number B. burgdorferi clinical isolates (I. Schwartz et al., unpublished data). However, no differences in the growth curves were observed for any cultures, regardless of medium composition (Fig. 1A), suggesting that variations in media had no major influence on the in vitro growth of the two B. burgdorferi clinical isolates examined.

FIG. 1.

Growth curves of B. burgdorferi isolates B515 and BL206 cultured in different BSK media (A) and the measured average diameters of ankle joints of C3H/HeJ mice inoculated with different variants of B. burgdorferi clinical isolates (B). B. burgdorferi was cultured in BSK-H medium until mid-log phase and passaged in either BSK-H or BSK-S medium. Numbers of spirochetes were enumerated on the indicated days by dark-field microscopy (28). The reported diameters are averages for ankle joints from five to six mice tested with each variant. **, P < 0.01.

However, in the first experiment, B. burgdorferi was recovered only from 1 ear biopsy specimen from mice inoculated with isolate B515 cultured in BSK-H2 medium, whereas 24 of 30 (80.0%) samples collected from mice infected with isolate B515 grown in BSK-S medium were positive by culture (Table 2) (P < 0.0001, Fisher's exact test). Overall, all mice (six of six) inoculated with isolate B515 passaged in BSK-S medium were infected, whereas only one of six (17%) mice injected with isolate B515 cultured in BSK-H2 medium showed evidence of infection (P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test). Moreover, the pathogenicity of this isolate was attenuated when it was grown in BSK-H2 medium; on days 14, 21, and 28, the average ankle joint diameters of mice infected with isolate B515 passaged in BSK-S medium were significantly greater than for those of mice infected with the same isolate grown in BSK-H2 medium (Fig. 1B) (P was <0.01 for all, as determined by the two-tailed Student t test).

TABLE 2.

Infectivities and pathogenicities of B. burgdorferi RST1 clinical isolates as determined with a C3H/HeJ murine model of Lyme borreliosis after isolates were grown in different BSK media in prospective experiments

| Borrelia isolate | Passage | BSK mediuma | No. of mice | Culture positivity of indicated specimensb

|

Infectivityc (%) | Pathogenicityd (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Ear | Heart | Bladder | ||||||

| B515 | mp3 | BSK-H2 | 6 | 0/12 | 1/12 | NT | 0/4 | 1/6 (17) | 1/6 (17) |

| BSK-S | 6 | 7/12 | 12/12 | NT | 5/6 | 6/6 (100)** | 6/6 (100)** | ||

| BL206 | p3 | BSK-H3 | 5 | 3/10 | 8/10 | 1/5 | NT | 4/5 (80) | 4/5 (80) |

| BSK-S | 5 | 2/10 | 10/10 | 2/5 | NT | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 (100) | ||

| B515 | mp4 | BSK-H3 | 4 | 3/3 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 (100) | 4/4 (100) |

| BSK-S | 2 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 (100) | 2/2 (100) | ||

BSK-H2 and BSK-H3 refer to different lots of BSK-H medium (Sigma); BSK-S is a BSK medium prepared in-house.

Number of positive cultures/number of cultured specimens that were collected between days 14 and 28 postinoculation. Contaminated cultures were excluded. NT, not tested.

Number of mice infected/number of mice examined in each group.

Pathogenicity was determined by measurement of the ankle joint swelling and/or by histopathology of one ankle joint for each mouse. **, P < 0.01 in comparison to data from variants grown in BSK-H2 medium.

In a second experiment, B. burgdorferi isolate BL206 was cultivated in parallel in BSK-S medium and a different lot of BSK-H medium (BSK-H3) and infectivity and pathogenicity in C3H/HeJ mice were evaluated. All five mice inoculated with isolate BL206 passaged in BSK-S medium and four of five mice inoculated with isolate BL206 cultured in BSK-H3 medium were infected and developed apparent ankle joint swelling (P > 0.05) (Table 2). Similar results were observed for B. burgdorferi isolate B515 grown in BSK-H3 and BSK-S media, suggesting that there is lot variation in BSK-H medium and that BSK-H3 is good for supporting in vitro growth and for assessing the infectivity of virulent B. burgdorferi clinical isolates. Taken together, the retrospective and prospective studies demonstrate that variations in BSK media can have significant effects on the infectivity and pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi clinical isolates, although these media are sufficient for supporting the in vitro growth of B. burgdorferi.

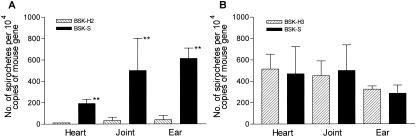

To determine if B. burgdorferi disseminated in culture-negative mice, the numbers of spirochetes in heart, joint, and ear biopsy specimens of mice were determined by a real-time quantitative PCR assay in 96-well microplates in an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.). The B. burgdorferi-specific fla and mouse-specific glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) genes were amplified simultaneously for each sample with the use of external standard sets for each gene as described previously (26). The numbers of spirochetes in each PCR were calculated by comparing the threshold cycle number of the sample with those of the standards with the ABI sequence detection systems software (SDS 2.0; Applied Biosystems) and were normalized to 104 copies of the mouse GAPDH gene. Significantly higher spirochete loads were observed in heart, joint, and ear biopsy specimens of mice infected with B. burgdorferi isolate B515 grown in BSK-S medium than in those inoculated with B515 passaged in BSK-H2 medium (Fig. 2) (P was <0.01 for all by the two-tailed Student t test).

FIG. 2.

Spirochete loads in heart, joint, and ear biopsy specimens of mice inoculated with B. burgdorferi clinical isolates B515 (A) and BL206 (B) cultured in different BSK media. Numbers of spirochetes are averages of results for five to six mice in each group as determined by a multiplex, real-time quantitative PCR assay as described in the text. **, P < 0.01.

It is not clear why the infectivities of previously pathogenic B. burgdorferi clinical isolates decreased as a result of brief passage in BSK-H2 medium, but several factors may contribute to the observed phenomenon. These include (i) the loss of a portion of the B. burgdorferi genome, particularly plasmids; (ii) differential gene and/or surface protein expression; (iii) selective overgrowth of clonal populations with a lower level of infectivity; and (iv) modulation of the spirochetal surface by differential binding with medium components.

Cultivation of B. burgdorferi in vitro can result in the loss of certain plasmids (23) and lead to a heterogeneous population with different plasmid profiles (8). Moreover, several studies reported a potential correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in B. burgdorferi (12, 22, 32), suggesting that the observed decrease in pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi isolates in the present study may be due to the loss of plasmids containing genes encoding proteins required for pathogenesis. The plasmid contents of the two variants of B. burgdorferi isolate B515 (i.e., grown in BSK-H2 and BSK-S) were analyzed using plasmid-specific PCR as previously described (10). The presence of 22 plasmids, including 10 linear plasmids (lp56, lp54, lp38, lp36, lp28-1, lp28-2, lp28-3, lp28-4, lp25, and lp17) and 12 circular plasmids (cp26, cp32-1 to cp32-9, cp32-11, and cp9), was evaluated. All plasmids analyzed except for cp9 were detected in both variants of B. burgdorferi isolate B515 regardless of growth medium, demonstrating that the decrease in pathogenicity of isolate B515 after cultivation in BSK-H2 medium was not due to the loss of plasmids.

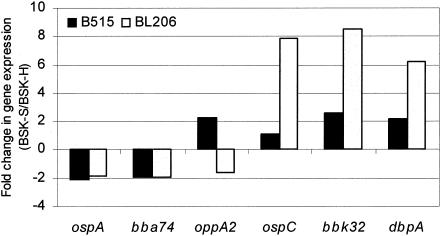

Differential gene expression of B. burgdorferi in response to a variety of environmental stimuli or during different stages of its life cycle has been reported (18, 24). B. burgdorferi isolate B31 maintained in a natural, zoonotic cycle or in culture showed clearly different levels of expression of a subset of antigens and a variation in infectivity (7). B. burgdorferi isolates with differential gene expression profiles may possess distinct pathogenic properties (2). Recently, several differentially expressed genes were identified in B. burgdorferi strain 297 variants cultivated in BSK-II or BSK-H (33). To investigate potential differences in levels of gene expression in our study, the relative levels of expression of six representative genes (ospA, bba74, oppA2, ospC, bbk32, and dbpA), whose expression levels changed during temperature shift experiments (18), was determined by real-time reverse transcription-PCR assays with primers described previously (9, 18) and with forward primer 5′-CCATTTTAATGTAAAATCTAAGTG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GTTAATTCTCCTTATTTAAAC-3′ for bba74. Differential expression between B. burgdorferi variants grown in distinct BSK media could be demonstrated (Fig. 3). It is likely that growth of B. burgdorferi clinical isolates in distinct BSK media triggers differential expression of virulence-related genes and/or proteins, resulting in the observed variability in infectivity and pathogenicity, although a correlation between the gene expression pattern of an isolate and its infectivity was not observed based on analysis of the mRNA levels for this limited number of genes.

FIG. 3.

Relative levels of gene expression of B. burgdorferi isolates grown in different BSK media as determined by real-time reverse transcription-PCR. The expression levels of representative genes were normalized to that of the flagellin gene and are expressed as the change in expression (n-fold) between B. burgdorferi isolates grown in BSK-S medium and those grown in BSK-H medium.

Alternatively, the original uncloned clinical isolate B515 might contain mixed populations of various pathogenicities, of which one or more clones with lower pathogenicities are overgrown and become predominant in culture as a result of the variations in BSK medium (16, 17). Finally, there are 50 and 26 g of BSA per liter of BSK-H and BSK-S medium, respectively. Effects of BSA lot variation on the culture of B. burgdorferi have been reported (6). It is possible that variations in the components of different BSK media, or in the quality of certain chemicals in different lots of BSK-H medium, cause the medium to bind differentially to the spirochetal surface, thus modulating the surface structure and, thereby, the host responses. For example, a B. burgdorferi variant that is more readily recognized by the host immune system will be cleared by the host, whereas other variants with a different surface may evade the host immune response and establish infection in mice.

In conclusion, our data suggest that variations in BSK medium formulations have significant effects on the infectivity and pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi clinical isolates. The attenuated pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi variants cultured in BSK-H medium is not due to the loss of plasmids. Further studies are in progress to compare the differences in levels of gene expression and in the protein profiles of variants of B. burgdorferi clinical isolates grown in various BSK media.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by NIH grants AR41511 and AI45801.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, J. F., S. W. Barthold, and L. A. Magnarelli. 1990. Infectious but nonpathogenic isolate of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:2693-2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anguita, J., S. Samanta, B. Revilla, K. Suk, S. Das, S. W. Barthold, and E. Fikrig. 2000. Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression in vivo and spirochete pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 68:1222-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour, A. G. 1984. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J. Biol. Med. 57:521-525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benach, J. L., E. M. Bosler, J. P. Hanrahan, J. L. Coleman, G. S. Habicht, T. F. Bast, D. J. Cameron, J. L. Ziegler, A. G. Barbour, W. Burgdorfer, R. Edelman, and R. A. Kaslow. 1983. Spirochetes isolated from the blood of two patients with Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 308:740-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgdorfer, W., A. G. Barbour, S. F. Hayes, J. L. Benach, E. Grunwaldt, and J. P. Davis. 1982. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 216:1317-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callister, S. M., K. L. Case, W. A. Agger, R. F. Schell, R. C. Johnson, and J. L. Ellingson. 1990. Effects of bovine serum albumin on the ability of Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly medium to detect Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:363-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golde, W. T., and M. C. Dolan. 1995. Variation in antigenicity and infectivity of derivatives of Borrelia burgdorferi, strain B31, maintained in the natural, zoonotic cycle compared with maintenance in culture. Infect. Immun. 63:4795-4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimm, D., A. F. Elias, K. Tilly, and P. A. Rosa. 2003. Plasmid stability during in vitro propagation of Borrelia burgdorferi assessed at a clonal level. Infect. Immun. 71:3138-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodzic, E., S. Feng, K. J. Freet, and S. W. Barthold. 2003. Borrelia burgdorferi population dynamics and prototype gene expression during infection of immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice. Infect. Immun. 71:5042-5055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyer, R., O. Kalu, J. Purser, S. Norris, B. Stevenson, and I. Schwartz. 2003. Linear and circular plasmid content in Borrelia burgdorferi clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 71:3699-3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly, R. 1971. Cultivation of Borrelia hermsii. Science 173:443-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labandeira-Rey, M., and J. T. Skare. 2001. Decreased infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is associated with loss of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1. Infect. Immun. 69:446-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liveris, D., S. Varde, R. Iyer, S. Koenig, S. Bittker, D. Cooper, D. McKenna, J. Nowakowski, R. B. Nadelman, G. P. Wormser, and I. Schwartz. 1999. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme disease patients as determined by culture versus direct PCR with clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:565-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma, Y., K. P. Seiler, E. J. Eichwald, J. H. Weis, C. Teuscher, and J. J. Weis. 1998. Distinct characteristics of resistance to Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis in C57BL/6N mice. Infect. Immun. 66:161-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson, J. A., J. K. Bouseman, U. Kitron, S. M. Callister, B. Harrison, M. J. Bankowski, M. E. Peeples, B. J. Newton, and J. F. Anderson. 1991. Isolation and characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi from Illinois Ixodes dammini. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:1732-1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris, D. E., B. J. B. Johnson, J. Piesman, G. O. Maupin, J. L. Clark, and W. C. Black IV. 1997. Culturing selects for specific genotypes of Borrelia burgdorferi in an enzootic cycle in Colorado. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2359-2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norris, S. J., J. K. Howell, S. A. Garza, M. S. Ferdows, and A. G. Barbour. 1995. High- and low-infectivity phenotypes of clonal populations of in vitro-cultured Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 63:2206-2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ojaimi, C., C. Brooks, S. Casjens, P. Rosa, A. Elias, A. Barbour, A. Jasinskas, J. Benach, L. Katona, J. Radolf, M. Caimano, J. Skare, K. Swingle, D. Akins, and I. Schwartz. 2003. Profiling of temperature-induced changes in Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression by using whole genome arrays. Infect. Immun. 71:1689-1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Picken, M. M., R. N. Picken, D. Han, Y. Cheng, E. Ruzic-Sabljic, J. Cimperman, V. Maraspin, S. Lotric-Furlan, and F. Strle. 1997. A two year prospective study to compare culture and polymerase chain reaction amplification for the detection and diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Mol. Pathol. 50:186-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollack, R. J., S. R. Telford III, and A. Spielman. 1993. Standardization of medium for culturing Lyme disease spirochetes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1251-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preac-Mursic, V., B. Wilske, and G. Schierz. 1986. European Borrelia burgdorferi isolated from humans and ticks: culture conditions and antibiotic susceptibility. Zentbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. Ser. A 263:112-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Purser, J. E., and S. J. Norris. 2000. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13865-13870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwan, T. G., W. Burgdorfer, and C. F. Garon. 1988. Changes in infectivity and plasmid profile of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, as a result of in vitro cultivation. Infect. Immun. 56:1831-1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwan, T. G., and J. Piesman. 2000. Temporal changes in outer surface proteins A and C of the Lyme disease-associated spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, during the chain of infection in ticks and mice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:382-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steere, A. C., R. L. Grodzicki, A. N. Kornblatt, J. E. Craft, A. G. Barbour, W. Burgdorfer, G. P. Schmid, E. Johnson, and S. E. Malawista. 1983. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 308:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, G., Y. Ma, A. Buyuk, S. McClain, J. J. Weis, and I. Schwartz. 2004. Impaired host defense to infection and Toll-like receptor 2-independent killing of Borrelia burgdorferi clinical isolates in TLR2-deficient C3H/HeJ mice. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, G., C. Ojaimi, R. Iyer, V. Saksenberg, S. A. McClain, G. P. Wormser, and I. Schwartz. 2001. Impact of genotypic variation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto on kinetics of dissemination and severity of disease in C3H/HeJ mice. Infect. Immun. 69:4303-4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, G., C. Ojaimi, H. Wu, V. Saksenberg, R. Iyer, D. Liveris, S. A. McClain, G. P. Wormser, and I. Schwartz. 2002. Disease severity in a murine model of Lyme borreliosis is associated with the genotype of the infecting Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto strain. J. Infect. Dis. 186:782-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wooten, R. M., and J. J. Weis. 2001. Host-pathogen interactions promoting inflammatory Lyme arthritis: use of mouse models for dissection of disease processes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:274-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wormser, G. P., S. Bittker, D. Cooper, J. Nowakowski, R. B. Nadelman, and C. Pavia. 2000. Comparison of the yields of blood cultures using serum or plasma from patients with early Lyme disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1648-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wormser, G. P., D. Liveris, J. Nowakowski, R. B. Nadelman, L. F. Cavaliere, D. McKenna, D. Holmgren, and I. Schwartz. 1999. Association of specific subtypes of Borrelia burgdorferi with hematogenous dissemination in early Lyme disease. J. Infect. Dis. 180:720-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu, Y., C. Kodner, L. Coleman, and R. C. Johnson. 1996. Correlation of plasmids with infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto type strain B31. Infect. Immun. 64:3870-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang, X., T. G. Popova, M. S. Goldberg, and M. V. Norgard. 2001. Influence of cultivation media on genetic regulatory patterns in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 69:4159-4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]