Abstract

The 3D7 form of the merozoite surface protein 2 (MSP2) of Plasmodium falciparum was one of three subunits of the malaria vaccine Combination B that were tested in a phase I/IIb double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial, which was undertaken with 120 Papua New Guinean children of 5 to 9 years of age. Because only one variant of the highly polymorphic MSP2 was used for vaccination, we examined whether the elicited response was directed against conserved or strain-specific epitopes. Postvaccination (week 12) titers of antibody against recombinantly expressed individual domains of MSP2 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and compared to baseline values. We found that vaccination with the 3D7 form of MSP2 induced a significant strain-specific humoral response directed against the repetitive and semiconserved family-specific part. The conserved N- and C-terminal domains were not immunogenic. Titers of antibody against the alternate FC27 family-specific domain showed a tendency to increase in vaccinated children, but there was no increase in antibodies against FC27-type 32-mer repeats. These results indicate that vaccination with one MSP2 variant mainly induced a strain-specific response, which can explain the selective effect of vaccination with combination B on the genotypes of breakthrough parasites. These findings support the inclusion of both family-specific domains (3D7 and FC27) in an improved vaccine formulation.

The antigenic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum represents a significant challenge for the development of a malaria vaccine. The merozoite surface protein 2 (MSP2) has been considered a candidate antigen despite being highly polymorphic. The different msp2 alleles, which differ in number and sequence of intragenic repeats, can be grouped into two allelic families, FC27 and 3D7, according to the central dimorphic domain (18).

The 3D7 allelic type of MSP2 formed one of three subunits of the malaria vaccine Combination B, which is one of the few malaria vaccines tested in a field trial so far. This subunit vaccine, consisting of the three recombinant proteins MSP1 (190LCS.T3), MSP2, and ring-infected erythrocyte surface antigen, was assessed in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase I/IIb trial (natural challenge) using 120 Papua New Guinean (PNG) children of 5 to 9 years of age (12). Montanide ISA720 was used as an adjuvant. The placebo doses consisted of adjuvant alone. Vaccination reduced parasite densities (the primary outcome) by 62%. It remains unclear which of the three vaccine components is responsible for this protection, but molecular monitoring provided evidence that this effect was at least partly due to the efficacy of the MSP2 component (6). The parasites in all blood samples collected during the trial in fortnightly intervals over 18 weeks were genotyped at the msp2 locus. When the effect of vaccination on parasite prevalence was assessed, the prevalence of parasites with a 3D7-type msp2 genotype was found to be significantly reduced, while the vaccine made no difference in the prevalence of parasites with an FC27-type msp2 genotype (12). Also, the vaccine effects on preventing new infections were significantly different for the two allelic families. Genotyping blood samples, collected from these 120 children over a period of 1 year following the trial during morbid episodes, revealed that vaccination led to an increase in incidence of morbid episodes with FC27-type MSP2 alleles. This was the first report of a selective effect exerted by vaccination with a polymorphic malaria vaccine (6, 12). The demonstration of a specific effect of the vaccine against the development of infections of the 3D7 type indicated that the activity of Combination B is due, at least in part, to the MSP2 component, which seems to protect children against homologous parasites.

This finding of vaccine-induced selection targeted at MSP2 prompted us to analyze the anti-MSP2 humoral immune response elicited by vaccination. By analyzing in great detail the effect of Combination B on (i) msp2 genotypes detected in trial participants and (ii) the strain-specific anti-MSP2 response, we hope to elucidate the effects observed in this field trial in PNG and gather important information for a future MSP2-based vaccine or for other polymorphic vaccines in general.

Of particular interest was the immunogenicity of the conserved N- and C-terminal domains, which could potentially confer immunity across all strains, in contrast to a strain-specific response indicated by antibodies against the intragenic repeats of the 3D7 allele. Immunogenicity of the 3D7 family-specific region could protect against all infecting parasites with an MSP2 of this family. We also investigated whether responses against different regions of the family-specific domain of the alternative FC27 allelic family were elicited. To quantify immune responses against the conserved, variable, or repetitive domains of MSP2, the corresponding fragments of the gene were cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli.

In the PNG trial, antibody responses were elicited against all three antigens included in the vaccine (11). A significant increase in the anti-MSP2 antibody level was observed in response to vaccination. The serological analysis was performed using the full-length 3D7 type of MSP2 antigen, which was included in the Combination B vaccine. These tests did not permit delineation of the response with respect to the different domains of MSP2.

In anticipation of further vaccine trials of MSP2, there is a need to analyze what effects could have been responsible for the protection observed in the recent trial and why these effects did not protect completely. We were particularly interested in exploring whether vaccination induced an immunological response against the conserved parts of the molecules or specifically against the 3D7 family-specific domain. In light of the limited natural recognition of the conserved domains of MSP2 (14), performing such analyses with samples from immunized children becomes crucial for deciding the composition of the next generation of an MSP2 vaccine. We also investigated whether antimalarial pretreatment led to increased immunogenicity of the vaccine, as has been proposed previously (3, 10).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area and study design.

The study was conducted in four villages of the Wosera District of the East Sepik Province of PNG. The study area shows intense and perennial malaria transmission. Entomological inoculation rates were estimated to be 35 infectious bites per year for P. falciparum. One hundred twenty children from ages 5 to 9 years were enrolled in the double-blind, block-randomized (within age groups), four-arm, placebo-controlled trial to assess safety, immunogenicity, and pilot efficacy of the Combination B vaccine. Since it has been debated whether preexisting infections should be cleared before immunization, half the children were pretreated with sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) (Fansidar; Hoffmann LaRoche, Basel, Switzerland) at baseline (week −1). Injections were given twice, at weeks 0 and 4.

Blood samples were collected at baseline and every 2 weeks from weeks 4 to 18. The primary outcomes of the trial were the rate of adverse events and the geometric mean P. falciparum parasite density (assessed for all positive samples from weeks 8 to 18).

Ethical clearance was obtained from the PNG Medical Research Advisory Committee. Detailed study procedures were described previously (11).

Cloning of recombinant msp2 constructs.

The different MSP2 domains were PCR amplified and cloned in the pQE30 expression vector (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.), providing an N-terminal His6 tag. The primers and msp2 alleles used as a template for amplification are given in Table 1. A recombinant FC27 family-specific domain was generated by ligating two PCR products representing the region upstream of the 32-mer repeats and the region downstream of the 12-mer, respectively. The restriction sites necessary for ligating the two PCR fragments gave rise to three additional residues, arginine, asparagine, and serine, which are not found at this position in wild-type MSP2 variants. Cloning of N- and C-terminal constant domains was described previously (8). All constructs cloned in E. coli were confirmed by DNA sequencing on an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin-Elmer). Accession numbers are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequences and accession numbers of MSP2 constructs

| Antigen | Primer sequence (restriction site)a | Accession no. (allele) | Recombinant protein sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D7 family-specific domain | 5′-cgggatcccgTGGTAATGGTGCT-3′ (BamHI) | M60188 (FCR3) | MRGS-HHHHHH-GSR-(FCR3 aab 109-214)-GYPGSTCSQA |

| 5′-ggggtaccccAGATTGTAATTCG-3′ (KpnI) | |||

| FC27 family-specific domain | |||

| 5′ part | 5′-cgggatcccgTAAGAGTGTAGGTG-CAAATGCTCCAAAAggaattcc-3′ (BamHI/EcoRI) | M59766 (K1) | MRGS-HHHHHH-GSRKSVGANAPK-GIP-(FC27 fsp)-APQEP |

| 5′-ggaattcc (EcoRI) | |||

| Fused to 3′ part | 5′-gggattccAGAAAGTTCAAGTT-3′ (EcoRI) | MS9766 (K1) | QTAENENPA-GYPGSTCSQA |

| 5′-ggggtaccccAGCAGGATTTTCA-3′ (KpnI) | |||

| FC27-type repeat (32aa)4 | 5′-cgggatcccgTGCTCCAAAAGCT-3′ (BamHI) | AY532388 (lfa 45) | MRGS-HHHHHH-GSR-APK-(32-aa repeat)4-ADTP-GYPGSTCSQA |

| 5′-ggggtaccccAGGGGTATCAGCA-3′ (KpnI) |

Lowercase nucleotides indicate mismatches with respect to the msp2 nucleotide sequence; underlined nucleotides indicate restriction sites used for cloning.

aa, amino acid.

Antigen preparation.

Five recombinant antigens corresponding to different MSP2 domains were expressed as His6-tagged proteins in E. coli strain M15 (QIAGEN) and purified under denaturing conditions (8 M urea) by use of a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid column in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (QIAGEN). The reactivities of the antigens were assessed by immunoblot analysis using a serum pool of 20 semi-immune adults from PNG. The concentrations of purified antigens were determined with a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce). The recombinant proteins correspond to the conserved N-terminal part, the conserved C-terminal part, the 3D7 family-specific part, the FC27 family-specific part, and an FC27-type 32-amino-acid sequence repeated four times. We failed to recombinantly express the 4-mer repeat glycine-glycine-serine-alanine (GGSA) of the 3D7 strain. Therefore, a synthetic peptide (molecular size, 1,379 Da) corresponding to (GGSA)5 was used. This peptide was kindly provided by Giampietro Corradin, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Determination of antibody titers.

Titers of antibody against the above-mentioned antigens were determined by a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Immulon 2HB plates (Thermo Labsystems, Franklin, Mass.) were coated overnight with 50 μl of antigen at a concentration of 2 μg/ml (recombinant proteins) or 10 μg/ml (synthetic peptide). Plates were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% nonfat milk powder. Antibody reactions were carried out in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% milk powder and 0.05% Tween 20. Serum samples were serially diluted threefold starting from a 1:50 dilution. A pool of serum from 20 adults from PNG was used as an internal standard at a dilution specific for each antigen to give an optical density of about 1. Dilutions of the serum pool were 1:10,000 for the 3D7 family-specific domain and for the FC27-type repeat, 1:1,200 for the FC27 family-specific domain, and 1:100 for the two conserved domains and for the 3D7-type repeat.

The plates were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Plate washing was performed with an ELISA washer with water containing 0.05% Tween 20. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) was used as a secondary antibody at a 1:4,000 dilution and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After extensive washing, ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid)] peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry) was added. The reaction was stopped after 30 min with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and the optical densities of the plates were read at 405 nm. Antibody titers were determined from the last dilution giving an optical density above 0.1 after standardization and background subtraction (same serum dilution on the uncoated plate).

PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism genotyping.

IsoCode STIX PCR template preparation dipsticks (Schleicher & Schuell, Inc., Keene, N.H.) were used for transport and storage of blood pellets after removal of serum from all blood samples collected during the study. Isolation of P. falciparum DNA and msp2 genotyping were performed as previously described (7). Genotyping of FC27-type alleles was done by a HinfI restriction digestion. To identify each 3D7-type allele unequivocally, additional DdeI and ScrFI digestions were done.

Statistical analysis.

For each child, the ratio of the titer at week 12 to that at baseline (week −1) was computed. Two sample t tests were used to test the statistical significance of the difference in this ratio between the placebo and vaccine groups. To evaluate whether the diversity of infecting parasites modified the level of antibody, Spearman correlations were computed between the mean multiplicity of infection (MOI) from weeks 4 to 12 and the specific antibody titers at week 12. To ascertain whether any specific antibody appeared to be protective, the correlations were computed between the mean MOI from weeks 14 to 18 and the antibody titers at week 12.

RESULTS

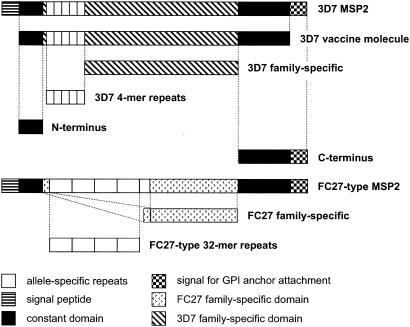

The different MSP2 domains used for ELISA are depicted schematically in Fig. 1. We failed to express the 3D7 repeats in E. coli; therefore, a synthetic peptide was used.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of recombinant and synthetic MSP2 antigens used for ELISA. The constructs are aligned with full-length MSP2 alleles representing the two allelic families of MSP2. The 3D7 vaccine molecule included in Combination B is also shown.

Effect of vaccination.

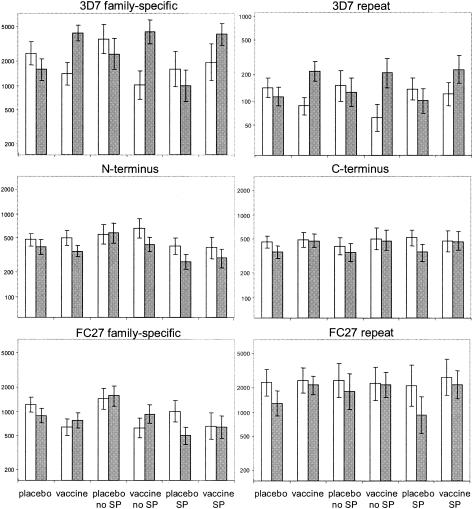

The responses against the MSP2 component of the Combination B vaccine were compared among the four study groups, i.e., those receiving either (i) vaccine with no SP, (ii) placebo with no SP, (iii) vaccine with SP, or (iv) placebo with SP. Serum samples analyzed were derived from the baseline survey of the vaccine trial at week −1 and from the parasitological survey at week 12 after vaccination. We chose sera collected at week 12 because titers of IgG against the full-length MSP2 vaccine molecule were found to peak in vaccinated children at this time (11). Figure 2 gives the average titers to all six antigens for the four treatment groups. To test for vaccine effects, the ratio of the antibody titers of the two time points was determined for each child. Table 2 shows the effect of vaccination on this ratio. A significant increase in anti-MSP2 antibody titers in vaccinated children was found for the 3D7-specific antigens. The increase was 4.9-fold (95% confidence interval, 2.72 to 8.83) for the 3D7 family-specific domain and 3.1-fold (95% confidence interval, 1.97 to 4.86) for the 3D7 repeats (P < 0.0001). The Combination B vaccine did not significantly increase the titers of antibody against the FC27 32-mer repeats or the conserved N- or C-terminal domains. In contrast, titers of antibody against the FC27 family-specific domain decreased in the placebo group but remained almost constant in the vaccine group, leading to an overall positive effect of vaccination (Fig. 2). Thus, this latter result must be viewed with care.

FIG. 2.

IgG responses of different treatment groups to recombinant and synthetic MSP2 constructs. Geometric means of titers are shown for each treatment group to all tested antigens: conserved N terminus, conserved C terminus, 3D7 family-specific domain, 3D7 4-mer repeat, FC27 family-specific domain, and FC27 32-mer repeat. White columns represent titers at baseline; gray columns represent titers at week 12 postvaccination with combination B. Standard errors are indicated. The numbers of tested sera at baseline and week 12, respectively, for the different groups were as follows: placebo, 56 and 57; vaccine, 56 and 58; placebo with no SP, 29 and 29; vaccine with no SP, 29 and 30; placebo with SP, 27 and 28; and vaccine with SP, 27 and 28.

TABLE 2.

Effect of vaccine and of SP pretreatmenta

| Antigen | Vaccine

|

SP pretreatment

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ψν | 95% CI | t | P | ψt | 95% CIb | t | P | |

| Conserved N terminus | 0.84 | 0.56 1.27 | −1.24 | 0.2 | NS | |||

| Conserved C terminus | 1.23 | 0.87 1.76 | 1.17 | 0.2 | NS | |||

| 3D7 family specific | 4.90 | 2.72 8.83 | 5.12 | <0.0001 | NS | |||

| 3D7 repeat | 3.10 | 1.97 4.86 | 4.88 | <0.0001 | NS | |||

| FC27 family specific | 1.57 | 1.04 2.37 | 2.11 | 0.037 | 0.59 | 0.39-0.89 | −2.49 | 0.01 |

| FC27 repeat | 1.42 | 0.90 2.23 | 1.5 | 0.14 | NS | |||

ψv = xv,12xp,−1/xv,−1xp,12, where xv,−1 is the geometric mean titer in the vaccine group at baseline, xp,−1 is the geometric mean titer in the placebo group at baseline, xv,12 is the geometric mean week 12 titer in the vaccine group, xp,12 is the geometric mean week 12 titer in the placebo group, and ψ, is the corresponding ratio testing the effect of SP treatment rather than of vaccination. A value of 1 for ψν or ψt corresponds to no effect.

CI, confidence interval; NS, not significant.

Effect of SP treatment prior to vaccination.

Half of the children (30 vaccine treated and 30 placebo treated) were pretreated with SP in the week prior to the first immunization. To identify whether this pretreatment modified the antibody response, we carried out a comparison of the responses in the SP-treated and untreated groups. We found no significant effect of SP treatment on the ratio of week 12 titer to baseline titer for any of the antigens corresponding to the vaccine molecule, nor were the responses against the N- and C-terminal constant domains or to the FC27 32-mer repeat affected by prevaccine treatment. The only effect of SP treatment was observed for the FC27 family-specific domain. Children who did receive SP showed reduced titers of antibody against this FC27 domain (Table 2).

We also tested for a possible interaction between antimalarial treatment and vaccine effect. SP treatment did not significantly modify the effect of vaccination on any of the titers.

Effect of present or new infections.

In order to assess whether P. falciparum infections present during the trial period influenced the serological outcomes independently of the effect of vaccination, we calculated Spearman correlations between antibody titers and the mean MOIs determined by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism. This was done separately for the MOIs of FC27- and 3D7-type parasites. The MOI was chosen as the end point because it reflects the exposure during that period. The initial analyses considered only children who were not treated with SP (59 children in the placebo and vaccine groups), since SP-treated children remained largely uninfected. Among the untreated children, there were no significant relationships between the mean MOI from weeks 4 to 12 of either the 3D7 or the FC27 type of parasites and any antibody at week 12, suggesting that stimulation by recent infections had little effect on the antibody levels. In particular, titers of antibody against the 3D7 family-specific domain of MSP2, which were significantly increased by vaccination, showed no significant correlation to the MOI of 3D7-type parasites nor to the MOI of FC27-type parasites (correlation coefficients were −0.15 [P = 0.3] and 0.09 [P = 0.5], respectively).

When the SP-treated group was analyzed, no relationship was detected between the MOI and the levels of antibody against any of the antigens tested. However, when we determined the prospective effect of antibody levels measured at week 12 in all non-SP-treated children, irrespective of whether they had received placebo or vaccine, we found positive associations between antibodies against nonvaccine epitopes (FC27) and the mean MOI from weeks 14 to 18 (Table 3). This finding suggests that these antibodies reflect the long-term history of exposure of the host. There was little or no relationship between titers of antibody against vaccine epitopes (3D7) and post-week 12 MOIs, probably because the levels of these antibodies were modified by vaccination so that they no longer represented long-term exposure. This analysis included non-SP-treated children only in order to exclude the effects of this long-acting antimalarial drug on MOI.

TABLE 3.

Correlations between MOI (weeks 14 to 18) and antibody titer at week 12 irrespective of vaccinationa

| Antigen | 3D7 family

|

FC27 family

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman's ρ | P value | Spearman's ρ | P value | |

| Conserved N terminus | 0.41 | 0.001 | 0.27 | 0.04 |

| Conserved C terminus | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.04 |

| 3D7 family specific | 0.11 | 0.4 | 0.11 | 0.4 |

| 3D7 repeat | 0.14 | 0.3 | 0.09 | 0.5 |

| FC27 family specific | 0.38 | 0.003 | 0.35 | 0.007 |

| FC27 repeat | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.49 | <0.001 |

Results shown are for only the 59 non-SP-treated children with complete data. Calculation of MOI included samples with no infections. Mean MOI of 3D7-type infections, 0.24 (standard deviation, 0.40); mean MOI of FC27-type infections, 0.24 (standard deviation, 0.46).

DISCUSSION

The aim of including the conserved N- and C-terminal domains of MSP2 in a multicomponent vaccine was to elicit a strain-transcending immune response. We found that vaccination with Combination B did not induce an antibody response to either of the conserved termini of MSP2. This finding is consistent with generally low titers of naturally occurring antibodies to the conserved parts of MSP2 (14, 15, 20, 22, 24). Also, our recombinant constructs of the N- and C-terminal constant domains had been tested previously in immunoblots with a panel of sera of malaria-exposed adults and had shown only limited reactivities (8).

This finding contrasts with previous results from immunizations of mice suggesting that the conserved parts are immunogenic. Both a recombinant fusion of the conserved N and C termini (14) and short synthetic peptides representing parts of the conserved MSP2 regions (13) were immunogenic in mice. Humoral responses were elicited against the immunogens, but both studies reported very little reactivity with the full-length MSP2 protein.

Despite not being immunogenic in response to vaccination with Combination B, the conserved domains of MSP2 were recognized to be highly prevalent but generally to exist at low titers in all study groups. Our findings suggest that the conserved domains are antigenic to some extent in naïve individuals. However, vaccination or continuous natural exposure does not boost the response, indicating some tolerogenic properties of these parts of the molecule. This finding is also supported by our observation (unpublished) that titers of antibodies to conserved regions are generally found to be higher in young children than in semi-immune adults.

The repetitive domain of MSP2 is allele specific, and repeat sequences differ considerably between individual 3D7-type alleles. At week 12 postvaccination, we found significantly increased titers of IgG against the central repeat region in vaccinees. But it remains unclear how much the observed antirepeat response has contributed to protection against other 3D7-type parasite infections via cross-protective epitopes. The repeat unit GGSA of the 3D7 vaccine molecule occurs only rarely in the study area (unpublished observation). This finding is reflected by low baseline titers of anti-GGSA antibodies as opposed to high titers of antibodies to the FC27-type repeat (mean titers of 107 and 2,479, respectively). It might be possible that we failed to measure the entire anti-GGSA response in our ELISA because we used a short synthetic peptide [(GGSA)5] which may present the repeat in a conformation different from that in the full-length vaccine molecule. However, using this synthetic peptide for measuring the anti-GGSA response seems adequate in view of the high titers (>12,000) found in some sera after vaccination.

The anti-3D7 responses were impressive, with a 4.9-fold increase in titers of antibody against the family-specific domain in vaccinated children irrespective of SP treatment. This result is consistent with the previously described 2.5-fold increase in antibody titers against the entire 3D7 vaccine molecule (11). The result is also in line with a significant reduction in the prevalence of 3D7-type infections in the non-SP-treated vaccinated children (12).

The immunogenicity result supports the inclusion of the 3D7 family-specific domain in further vaccine formulations. Our finding suggests, but does not prove, that vaccine-induced anti-3D7 antibodies specifically protect against infections with parasites of the same allelic family, consistent with findings of cross-reactivity within the allelic family (8, 9). Whether the specific anti-3D7 response accounted for the vaccine-induced reduction in parasite densities remains open.

In trials of malaria vaccines (1, 2), insecticide-treated mosquito nets (for examples, see references 16 and 19), and drugs (21), participants are often pretreated with antimalarials in order to clear parasitemia and to allow determination of time to infection. Such treatment also has been advocated because of the immunosuppression during immunization caused by acute malaria infections and asymptomatic malaria parasitemia (3, 23). But pretreatment does reduce the statistical power to determine the primary end point for efficacy (e.g., parasite density as in the Combination B trial) and molecular measurements by preventing infections for much of the follow-up period. The benefits of pretreating vaccine trial participants have also been questioned on the grounds of effects on immune responses (4), adverse events, or resistance of parasites (5, 17). Our results from the PNG trial of Combination B showed no interaction between SP treatment and vaccine effect on anti-MSP2 antibody titers but dramatically reduced the statistical power of the trial to detect the parasitological effects of the vaccine.

SP treatment had a small but significant effect in reducing titers of antibody against the FC27 family-specific domain, the antigen not represented by the MSP2 variant included in the Combination B vaccine, presumably due to the reduction in exposure caused by the clearance of FC27-type parasites at baseline.

Genotyping all blood samples gave important information on whether the immune response to the MSP2 vaccine was modified by the presence of parasites, which is a topic of considerable interest in malaria vaccine trial design. There was no indication that exposure of the children studied to naturally presented malaria antigen primed them for additional boosting by the 3D7 vaccine component because antibody titers were unaffected by SP treatment. Also, multiplicity of 3D7-type infections did not affect titers of anti-3D7 antibody titers. Our finding is in agreement with a previous indication that a particular infecting MSP2 variant was not associated with the boosting of a strain-specific antibody response in semi-immune adults from Vietnam (24).

During the 1-year follow-up period after the trial of Combination B, an increase in morbidity associated with FC27-type alleles was observed, suggesting that the vaccine caused a selective effect favoring the allelic family not represented in the vaccine (12). Here we showed that the vaccine had only a small effect on specific anti-FC27 antibody titers, consistent with evidence that there is a limited degree of cross-reactivity between the two allelic families (8). However, by reducing the stimulus caused by 3D7-type infections, the vaccine may have reduced immune stimulation against other malaria epitopes and hence made the hosts more vulnerable to FC27 infections. Our results strongly encourage inclusion of both variants of the central dimorphic region in a future MSP2 vaccine.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study subjects and their families, the staff of the PNG Institute of Medical Research, and S. Märki and S. Steiger of the Swiss Tropical Institute for technical assistance.

This study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 31-062951).

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, P. L., T. Smith, J. R. Schellenberg, H. Masanja, S. Mwankusye, H. Urassa, I. Bastos de Azevedo, J. Chongela, S. Kobero, C. Menendez, N. Hurt, M. C. Thomas, E. Lyimo, N. A. Weiss, R. Hayes, A. Y. Kitua, M. C., Lopez, W. L., Kilama, T. Teuscher, and M. Tanner. 1994. Randomised trial of efficacy of SPf66 vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children in southern Tanzania. Lancet 344:1175-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bojang, K. A., P. J. Milligan, M. Pinder, L. Vigneron, A. Alloueche, K. E. Kester, W. R. Ballou, D. J., Conway, W. H., Reece, P. Gothard, L. Yamuah, M. Delchambre, G. Voss, B. M. Greenwood, A., Hill, K. P. McAdam, N. Tornieporth, J. D. Cohen, T. Doherty, and RTS,S Malaria Vaccine Trial Team. 2001. Efficacy of RTS,S/AS02 malaria vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum infection in semi-immune adult men in The Gambia: a randomised trial. Lancet 358:1927-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley-Moore, A. M., B. M. Greenwood, A. K. Bradley, A. Bartlett, D. E. Bidwell, A. Voller, J. Craske, B. R. Kirkwood, and H. M. Gilles. 1985. Malaria chemoprophylaxis with chloroquine in young Nigerian children. II. Effect on the immune response to vaccination. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 79:563-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bygbjerg, I. C., N. Odum, and T. G. Theander. 1986. Effect of pyrimethamine and sulphadoxine on human lymphocyte proliferation. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 80:295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulibaly, D., D. A. Diallo, M. A. Thera, A. Dicko, A. B. Guindo, A. K. Kone, Y. Cissoko, S. Coulibaly, A. Djimde, K. Lyke, O. K. Doumbo, and C. V. Plowe. 2002. Impact of preseason treatment on incidence of falciparum malaria and parasite density at a site for testing malaria vaccines in Bandiagara, Mali. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 67:604-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felger, I., B. Genton, T. Smith, M. Tanner, and H.-P. Beck. 2003. Molecular monitoring in malaria vaccine trials. Trends Parasitol. 19:60-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felger, I., A. Irion, S. Steiger, and H.-P. Beck. 1999. Genotypes of merozoite surface protein 2 of Plasmodium falciparum in Tanzania. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93(Suppl. 1):3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felger, I., S. Steiger, C. Hatz, T. Smith, and H.-P. Beck. 2003. Antigenic cross-reactivity between different alleles of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 2. Parasite Immunol. 25:531-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franks, S., L. Baton, K. Tetteh, E. Tongren, D. Dewin, B. D. Akanmori, K. A. Koram, L. Ranford-Cartwright, and E. M. Riley. 2003. Genetic diversity and antigenic polymorphism in Plasmodium falciparum: extensive serological cross-reactivity between allelic variants of merozoite surface protein 2. Infect. Immun. 71:3485-3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fryauff, D. J., S. J. Cryz, H. Widjaja, E. Mouzin, L. W. Church, M. A. Sutamihardja, A. L. Richards, B. Subianto, and S. L. Hoffman. 1998. Humoral immune response to tetanus-diphtheria vaccine given during extended use of chloroquine or primaquine malaria chemoprophylaxis. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1762-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genton, B., F. Al-Yaman, I. Betuela, R. F. Anders, A. Saul, K. Baea, M. Mellombo, J. Taraika, G. V. Brown, D. Pye, D. O. Irving, I. Felger, H.-P. Beck, T. A., Smith, and M. P. Alpers. 2003. Safety and immunogenicity of a three-component blood-stage malaria vaccine (MSP1, MSP2, RESA) against Plasmodium falciparum in Papua New Guinean children. Vaccine 22:30-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genton, B., I. Betuela, I. Felger, F. Al-Yaman, R. F. Anders, A. Saul, L. Rare, M. Baisor, K. Lorry, G. V. Brown, D. Pye, D. O. Irving, T. A. Smith, H.-P., Beck, and M. P. Alpers. 2002. A recombinant blood-stage malaria vaccine reduces Plasmodium falciparum density and exerts selective pressure on parasite populations in a phase 1-2b trial in Papua New Guinea. J. Infect. Dis. 185:820-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones, G. L., H. M. Edmundson, R. Lord, L. Spencer, R. Mollard, and A. J. Saul. 1991. Immunological fine structure of the variable and constant regions of a polymorphic malarial surface antigen from Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 48:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence, G., Q. Q. Cheng, C. Reed, D. Taylor, A. Stowers, N. Cloonan, C. Rzepczyk, A. Smillie, K. Anderson, D. Pombo, A. Allworth, D. Eisen, R. Anders, and A. Saul. 2000. Effect of vaccination with 3 recombinant asexual-stage malaria antigens on initial growth rates of Plasmodium falciparum in non-immune volunteers. Vaccine 18:1925-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metzger, W. G., D. M. Okenu, D. R. Cavanagh, J. V., Robinson, K. A. Bojang, H. A. Weiss, J. S. McBride, B. M., Greenwood, and D. J. Conway. 2003. Serum IgG3 to the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 2 is strongly associated with a reduced prospective risk of malaria. Parasite Immunol. 25:307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Msuya, F. H., and C. F. Curtis. 1991. Trial of pyrethroid impregnated bednets in an area of Tanzania holoendemic for malaria. Part 4. Effects on incidence of malaria infection. Acta Trop. 49:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owusu-Agye, S., F. Binka, K. Koram, F. Anto, M. Adjuik, F. Nkrumah, and T. Smith. 2002. Does radical cure of asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum place adults in endemic areas at increased risk of recurrent symptomatic malaria? Trop. Med. Int. Health 7:599-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smythe, J. A., M. G. Peterson, R. L. Coppel, A. J., Saul, D. J., Kemp, and R. F. Anders. 1990. Structural diversity in the 45-kilodalton merozoite surface antigen of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 39:227-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stich, A. H., C. A. Maxwell, A. A. Haji, D. M. Haji, A. Y. Machano, J. K. Mussa, A. Matteelli, H. Haji, and C. F. Curtis. 1994. Insecticide-impregnated bed nets reduce malaria transmission in rural Zanzibar. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 88:150-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor, R. R., D. B. Smith, V. J., Robinson, J. S. McBride, and E. M. Riley. 1995. Human antibody response to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 2 is serogroup specific and predominantly of the immunoglobulin G3 subclass. Infect. Immun. 63:4382-4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor, W. R., T. L. Richie, D. J., Fryauff, H. Picarima, C. Ohrt, D. Tang, D. Braitman, G. S. Murphy, H. Widjaja, E. Tjitra, A. Ganjar, T. R. Jones, H. Basri, and J. Berman. 1999. Malaria prophylaxis using azithromycin: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Irian Jaya, Indonesia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:74-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas, A. W., D. A. Carr, J. M., Carter, and J. A. Lyon. 1990. Sequence comparison of allelic forms of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface antigen MSA2. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 43:211-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Usen, S., P. Milligan, C. Ethevenaux, B. Greenwood, and K. Mulholland. 2000. Effect of fever on the serum antibody response of Gambian children to Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19:444-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weisman, S., L. Wang, H. Billman-Jacobe, D. H. Nhan, T. L., Richie, and R. L. Coppel. 2001. Antibody responses to infections with strains of Plasmodium falciparum expressing diverse forms of merozoite surface protein 2. Infect. Immun. 69:959-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]