Abstract

Human galectin-3 binds to the surface of Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes and human coronary artery smooth muscle (CASM) cells. CASM cells express galectin-3 on their surface and secrete it. Exogenous galectin-3 increased the binding of T. cruzi to CASM cells. Trypanosome binding to CASM cells was enhanced when either T. cruzi or CASM cells were preincubated with galectin-3. Cells stably transfected with galectin-3 antisense show a dramatic decrease in galectin-3 expression and very little T. cruzi adhesion to cells. The addition of galectin-3 to these cells restores their initial capacity to bind to trypanosomes. Thus, host galectin-3 expression is required for T. cruzi adhesion to human cells and exogenous galectin-3 enhances this process, leading to parasite entry.

Trypanosoma cruzi, the protozoan that causes Chagas' disease and infects 16 to 18 million people, uses host molecules to promote adhesion and entry into host cells to establish infection (13, 16). The elucidation of molecules that mediate T. cruzi infection will facilitate the understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of infection.

Human galectin-3 is a member of a growing family of β-galactosidase-binding animal lectins (18, 19). Recent evidence has implicated galectin-3 as a master regulator of inflammation, cell growth, signaling, chemotaxis, cell-matrix interactions, tumor progression, and metastasis (14, 19). Galectin-3 is expressed in a variety of tissues and cell types (3, 4, 6) and is localized in the cytoplasm, nucleus (12), or on the cell surface (5, 22) or is secreted in the extracellular environment by phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells (10, 22, 23). Because galectin-3 is secreted and is known to mediate cell adhesion of some immune cells (25), we have investigated the role of galectin-3 in the process of T. cruzi trypomastigote adhesion to coronary artery smooth muscle (CASM) cells. Here, we report a new mechanism by which T. cruzi uses galectin-3, which is secreted by human CASM cells, to mediate adhesion to these cells.

Galectin-3 binds to the surface of human cells and T. cruzi trypomastigotes in a lectin-like manner.

Highly purified endotoxin-free human recombinant galectin-3, expressed as a histidine-tagged protein (15, 26), was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (20) for binding assays (27). FITC-labeled galectin-3 (2 μg/ml of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was incubated with either 1% paraformaldehyde-fixed 30% confluent human CASM cell monolayers (Clonetics, San Diego, Calif.) or fixed cultured trypomastigotes (2 × 106) (9), in the presence or absence of lactose (5 mM) or a 100× excess of unlabeled recombinant galectin-3 in PBS supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at 37°C (27). Figure 1A shows that FITC-labeled galectin-3 binds to the surface of CASM cells. This binding is granular, distributed around the cellular membrane, polarized, and more pronounced at the cellular ends (Fig. 1A). These findings suggest that the receptors for human galectin-3 are distributed in patches on the surface of the cells and are more abundant at the terminal regions of the cells. The binding is specific, since a 100× excess of unlabeled galectin-3 completely inhibited the binding of labeled galectin-3 (Fig. 1B). The binding of labeled galectin-3 to the surface of CASM cells is completely inhibited by 5 mM lactose (Fig. 1C) but not by 5 mM sucrose (Fig. 1D), indicating that galectin-3 binds to the surface of CASM cells in a lectin-like manner. FITC-labeled galectin-3 also binds to the surface of trypomastigotes (Fig. 2A); this binding is inhibited by a 100× excess of unlabeled galectin-3 (Fig. 2B), indicating that it is specific. Lactose (Fig. 2C), but not sucrose (Fig. 2D), inhibited this binding, indicating that galectin-3 binds to the surface of trypomastigotes in a lectin-like manner. The binding of galectin-3 to trypomastigotes is also seen as granular, restricted to some areas of the membrane of trypanosomes, and polarized (Fig. 2A).

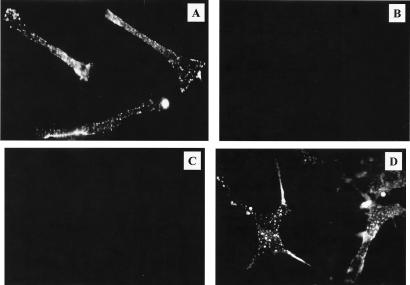

FIG. 1.

Human galectin-3 binds to the surface of human CASM cells in a lectin-like manner. Human CASM cell monolayers at 30% density were washed with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS), fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, and incubated with FITC-labeled galectin-3 (2 μg/ml) (A), 100× unlabeled galectin-3 plus FITC-labeled galectin-3 (B), 5 mM lactose plus FITC-labeled galectin-3 (C), or 5 mM sucrose plus FITC-labeled galectin-3 (D) for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed and examined under fluorescence microscopy. The results shown are from a representative experiment of three experiments performed with the same results.

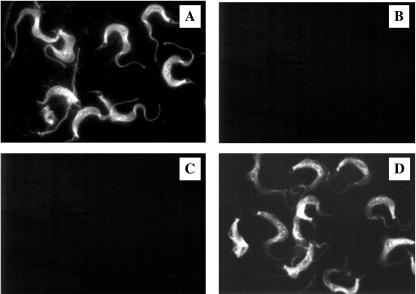

FIG. 2.

Human galectin-3 binds to the surface of T. cruzi trypomastigotes in a lectin-like manner. Culture trypomastigotes (2 × 106) were washed with HBSS, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, and incubated with FITC-labeled galectin-3 (2 μg/ml) (A), 100× unlabeled galectin-3 plus FITC-labeled galectin-3 (B), 5 mM lactose plus FITC-labeled galectin-3 (C), or 5 mM sucrose plus FITC-labeled galectin-3 (D) for 1 h at 37°C. Parasites were washed and examined under fluorescence microscopy. The results shown are from a representative experiment of three experiments performed with similar results.

Galectin-3 is expressed on the surface of CASM cells and is secreted.

We performed immunoprecipitation of biotinylated surface proteins of CASM cells with antibodies to galectin-3 as described previously (28). Figure 3A (left panel) shows that antibodies to human galectin-3 immunoprecipitate biotinylated surface galectin-3, whereas preimmune antibodies do not. To investigate whether galectin-3 is released into the cellular medium, we analyzed immunoblots of supernatant cultures of CASM cells incubated in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) for 6 h or in DMEM alone as described previously (2, 26, 28). Figure 3A (right panel) shows that antibodies to galectin-3 detect galectin-3 on the culture supernatant of CASM cells, whereas anti-galectin-3 antibodies did not react with medium alone, indicating that galectin-3 is released by CASM cells into the culture supernatant.

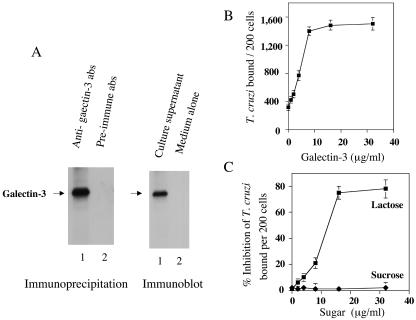

FIG. 3.

Galectin-3 is expressed on the surface of human CASM cells and is secreted, and exogenous galectin-3 enhances T. cruzi trypomastigote binding to human CASM cells. (A) Galectin-3 is expressed on the surface of human CASM cells and is secreted. Left panel, biotinylated surface proteins of human CASM cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-galectin-3 antibodies (abs) (lane 1) or with preimmune antibodies (lane 2), separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL). Right panel, immunoblots of culture supernatants of human CASM cells incubated in DMEM for 6 h (lane 1) or medium alone (lane 2), probed with anti-galectin-3 antibodies, and developed by ECL. (B) Galectin-3 enhances T. cruzi trypomastigote binding to human CASM cells. Triplicate monolayers of human CASM cells were exposed or not exposed to several concentrations of human galectin-3 free of endotoxin and to T. cruzi trypomastigotes at a ratio of 20 parasites per cell for 2 h at 37°C. Unbound parasites were washed out, and trypanosome binding was evaluated by using an immunofluorescence assay as described above. (C) Lactose, but not sucrose, inhibits T. cruzi trypomastigote binding to human CASM cells. Trypomastigote binding assays were performed as described for panel B in the presence of HBSS, with several concentrations of lactose or sucrose, at the ratio of 20 parasites per cell. Unbound trypanosomes were washed out, and binding was evaluated by immunofluorescence as for panel B. The results presented in panels A to C are from one respective representative experiment of three independent experiments performed with similar results. Each point in panels B and C is the mean of results for triplicate samples in one representative experiment (± 1 standard deviation). For panel B, the P value was <0.05 for differences between 0 (control) and ≥1 μg of galectin-3/ml. For panel C, the P value was <0.05 with Student's t test for differences between lactose and sucrose at all points except 0 μg of sugar/ml.

Galectin-3 enhances trypanosome adhesion to CASM cells in a lectin-like manner.

For binding assays, trypomastigotes were incubated with CASM cells at 30% confluence in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of galectin-3 (1 to 32 μg/ml) at the ratio of 20 parasites per cell for 2 h at 37°C in triplicate as described previously (9). Cells were stained with FITC-immunoglobulin G to the trypomastigote surface ligand (26, 27, 28) and DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole), and the numbers of bound fluorescent trypanosomes per 200 cells were determined. Galectin-3 enhances trypanosome binding to CASM cells in a concentration-dependent and saturable manner (Fig. 3B). The maximal enhancement effect of trypanosome binding to CASM cells was seen at 8 μg of galectin-3/ml. Galectin-3 increased the normal adhesion of trypomastigotes to CASM cells approximately five times; this effect is specific since it is inhibited by lactose in a concentration-dependent and saturable manner (Fig. 3C). Sucrose did not affect this interaction (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that the specificity of this effect is mediated by the β-galactoside-binding galectin-3. The increased binding of trypanosomes to CASM cells resulted in enhanced invasion under the conditions described previously (9, 27). Exogenous galectin-3 at a concentration of 8 μg/ml increased trypanosome entry by 319% ± 16% (P < 0.05) with respect to control CASM cells not exposed to galectin-3. This result is from a representative experiment of three experiments performed with the same results.

Preincubation of either trypomastigotes or CASM cells with galectin-3 enhances trypanosome adhesiveness to cells.

To determine which of the two cells, T. cruzi or CASM cells, is the primary facilitator of the galectin-3-mediated parasite-host interaction, the parasites and cells were preincubated with galectin-3 (4 μg/ml) followed by binding assays using a parasite-to-cell ratio of 10:1 (11). Figure 4 shows that the preincubation of either trypomastigotes or CASM cells with galectin-3 significantly enhanced the trypomastigote binding to cells with respect to mock-treated parasites or CASM cells. These results indicate that galectin-3 acts on either T. cruzi or CASM cells or on both types of cells in order to enhance parasite binding to host cells.

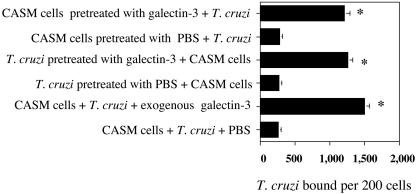

FIG. 4.

Trypanosome binding to CASM cells was enhanced when T. cruzi trypomastigotes or CASM cells were preincubated with galectin-3. Monolayers of human CASM cells or trypomastigotes were washed with HBSS and preincubated separately in PBS with 4 μg of galectin-3/ml. Parasites and cells were then incubated together at a ratio of 10 parasites per cell for 2 h at 37°C. Unbound trypanosomes were washed out, and trypanosome binding was evaluated by using an immunofluorescence assay as for Fig. 3B and C. Other controls included human CASM cells incubated with trypanosomes exposed or not exposed to galectin-3. Bars represent the means of results from triplicate samples in one representative experiment (± 1 standard deviation) selected from three experiments with similar results. *, significant difference compared to control values (P < 0.05).

Reduced expression of galectin-3 inhibits the attachment of T. cruzi to human cells, but the addition of exogenous galectin-3 restores the initial capacity of these cells to bind to trypanosomes.

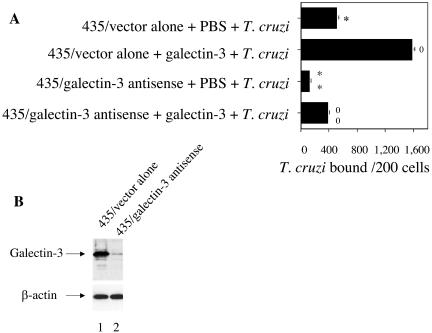

To investigate whether cell expression of galectin-3 plays a role in T. cruzi adhesion to cells, we used the 435 human breast epithelial cell line stably transfected with either pCNC10 vector alone or pCNC10-galectin-3 antisense selected as described previously (7). 435 cells transfected with the pCNC10 vector alone and with pCNC10-galectin-3 antisense were kindly provided by A. Raz. Results presented in Fig. 5 B indicate that cells stably transfected with galectin-3 antisense show a dramatically reduced expression of galectin-3 compared to cells transfected with vector alone, as indicated by immunoblot analysis. Blots stripped and probed with anti-β-actin antibodies indicated that the same amounts of protein were loaded in lanes 1 and 2 (Fig. 5B). Figure 5A shows that 435 cells transfected with galectin-3 antisense cells display a statistically significant reduction in the numbers of bound trypanosomes compared to cells transfected with the vector alone. The addition of exogenous galectin-3 to 435 cells transfected with galectin-3 antisense restores the initial capacity of these cells to bind to trypanosomes (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Reduced expression of galectin-3 inhibits the attachment of T. cruzi to human cells, but the addition of exogenous galectin-3 restores the initial capacity of these cells to bind to trypanosomes. (A) Blocking galectin-3 expression in human cells by transfection with galectin-3 antisense caused a reduction in T. cruzi adhesion to cells, and adding exogenous galectin-3 restores the initial capacity of these cells to bind to trypanosomes. Monolayers of human 435 cells transfected with vector alone or galectin-3 antisense were washed with HBSS and incubated separately with PBS or with 4 μg of galectin-3/ml in PBS and trypomastigotes at the ratio of 10 parasites per cell for 2 h at 37°C. Unbound trypanosomes were washed off, and trypanosome binding was evaluated by using an immunofluorescence assay as described for Fig. 3B. Bars represent the means of results for triplicate samples in one representative experiment (± 1 standard deviation) selected from three experiments with similar results. The difference between results labeled * and ** and the difference between results labeled 0 and 00 are significant (P < 0.05). (B) Human 435 cells transfected with galectin-3 antisense show significantly reduced expression of galectin-3 as evaluated by immunoblotting. Three μg of 435 cells transfected with either vector alone (lane 1) or galectin-3 antisense (lane 2) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, probed with anti-galectin-3 polyclonal antibodies, and developed by ECL. Loading controls were evaluated by stripping the same blots, probing them with anti-β-actin antibodies, and developing them by ECL. The results shown are from a representative experiment of three experiments performed with the same results. 435/vector alone, 435 cells transfected with pCNC10 vector alone; 435/galectin-3 antisense, 435 cells transfected with pCNC10-galectin-3 antisense.

Our results indicate that galectin-3 is expressed on the surface of and is secreted by human CASM cells and that exogenous galectin-3 enhances the binding of T. cruzi to human CASM cells. Our results also indicate that the cellular expression of galectin-3 is required for T. cruzi adhesion to human cells. The fact that exogenous human galectin-3 specifically binds to the surface of CASM cells and to T. cruzi suggests that galectin-3 bridges trypanosomes and cells, resulting in an enhancement of the binding of T. cruzi to human cells. Our results are consistent with the notion that galectin-3 can serve as an adapter for different types of molecules in other biological systems (8). Galectin-3 can bind glycoconjugates by means of its carbohydrate recognition domain region and can bind other molecules through its nonlectin half, therefore serving as a cross-linker between glycoconjugates and other molecules (8). Galectin-3 binds to the membrane of T. cruzi-containing surface glycoproteins. One such surface glycoprotein of invasive T. cruzi trypomastigotes that might play a role in this interaction is the gp83 ligand that mediates trypomastigote binding to different types of mammalian cells (27). Whether gp83 ligand binds to galectin-3 to enhance infection is presently unknown.

Galectin-3 is implicated in the association of T. cruzi with laminin (11), is expressed in B cells from T. cruzi-infected mice (1), and is up regulated by T. cruzi infection of mice (29). The fact that galectin-3 is secreted by macrophages and by other cells, including human CASM cells, as indicated in this report, suggests that released galectin-3 modulates infection. The concentrations of galectin-3 that increase trypanosome adhesion to CASM cells in vitro (Fig. 3B) are similar to the concentrations of galectin-3 present in fluids in vivo (21). Furthermore, the concentrations of galectin-3 in fluids in vivo increase approximately 300-fold during microbial infection (24). These observations suggest that this parasite may have adapted to the host and that it takes advantage of a host inflammatory molecule, galectin-3, to bind to host cells. Furthermore, it has been recently reported that Chagas' disease cardiomyopathy is in part a vasculopathy (17). We also suggest that the findings described in the present study may contribute in part to determining the cause of this pathology. In summary, we report that the expression of galectin-3 is required for T. cruzi infection and that the parasite uses galectin-3 to adhere to and enter human cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants GM 08037, GM 020054, AI 07281, P20 MD 000551, and HL 007737.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta-Rodriguez, E. V., C. L. Montes, C. C. Motran, E. I. Zuniga, F.-T. Liu, G. A. Rabinovich, and A. Gruppi. 2004. Galectin-3 mediates IL-4-induced survival and differentiation of B cells: functional cross-talk and implications during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Immunol. 172:493-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander, A. D., F. Villalta, and M. F. Lima. 2003. Transforming growth factor α binds to Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes to induce signaling and cellular proliferation. Infect. Immun. 71:4201-4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crittenden, S. L., C. F. Roff, and J. L. Wang. 1984. Carbohydrate-binding protein 35: identification of galactose-specific lectin in various tissues of mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:1252-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flotte, T. J., T. A. Springer, and G. J. Thorbecke. 1983. Dendritic cells and macrophages staining by monoclonal antibodies in tissue sections and epidermal sheets. Am. J. Pathol. 111:112-124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frigeri, L. G., and F.-T. Liu. 1992. Surface expression of functional IgE binding protein, an endogenous lectin, on mast cells and macrophages. J. Immunol. 148:861-869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gritzmacher, C. A., M. W. Robertson, and F.-T. Liu. 1988. IgE-binding protein. Subcellular location and gene expression in many murine tissues and cells. J. Immunol. 141:2801-2806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honjo, Y., P. Nangia-Makker, H. Inohara, and A. Raz. 2001. Down-regulation of galectin-3 suppresses tumorigenicity of human breast carcinoma cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 7:661-668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasai, K., and J. Hirabayashi. 1996. Galectins: a family of animal lectins that decipher glycocodes. J. Biochem. 119:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lima, M. F., and F. Villalta. 1989. Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigote clones differentially express a cell adhesion molecule. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 33:159-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindstedt, R., G. Apodaca, S. H. Barondes, K. E. Mostov, and H. Leffler. 1993. Apical secretion of a cytosolic protein by Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Evidence for polarized release of an endogenous lectin by a nonclassical secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 268:11750-11757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moody, T. N., J. Ochieng, and F. Villalta. 2000. Novel mechanism that Trypanosoma cruzi uses to adhere to the extracellular matrix mediated by human galectin-3. FEBS Lett. 470:305-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moutsatsos, I. K., M. Wade, M. Schindler, and J. L. Wang. 1987. Endogenous lectins from cultured cells: nuclear localization of carbohydrate-binding protein 35 in proliferating 3T3 fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:6452-6456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noisin, E. L., and F. Villalta. 1989. Fibronectin increases Trypanosoma cruzi binding to and uptake by murine macrophages and human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 57:1030-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochieng, J., V. Furtak, and P. Lukyanov. 2004. Extracellular functions of galectin-3. Glycoconj. J. 19:527-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochieng, J., D. Platt, L. Tait, V. Hogan, T. Raz, P. Carmi, and A. Raz. 1993. Structure-function relationship of a recombinant human galactoside-binding protein. Biochemistry 32:4455-4460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouaissi, M. A., D. Afchain, A. Capron, and J. A. Grimaud. 1984. Fibronectin receptors on Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes and their biological function. Nature 308:380-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petkova, S. B., H. Huang, S. M. Factor, R. G. Pestell, B. Bouzahzah, L. A. Jelicks, L. M. Weiss, S. A. Douglas, M. Wittner, and H. B. Tanowitz. 2001. The role of endothelin in the pathogenesis of Chagas' disease. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:499-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabinovich, G. A., N. Rubinstein, and L. Fainboim. 2002. Unlocking the secrets of galectins: a challenge at the frontier of glyco-immunology. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71:741-751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabinovich, G. A., L. G. Baum, N. Tinari, R. Paganelli, C. Notoli, F.-T. Liu, and S. Lacobelli. 2002. Galectins and their ligands: amplifiers, silencers or tuners of the inflammatory response. Trends Immunol. 23:313-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raz, A., and R. Lotan. 1981. Lectin-like activities associated with human and murine neoplastic cells. Cancer Res. 41:3642-3647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sano, H., D. K. Hsu, L. Yu, J. Apgar, I. Kuwabara, T. Yamanaka, M. Hirashima, and F.-T. Liu. 2000. Human galectin-3 is a novel chemoattractant for monocytes and macrophages. J. Immunol. 165:2156-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato, S., and R. C. Hughes. 1994. Regulation of secretion and surface expression of Mac-2, a galactoside-binding protein of macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 269:4424-4430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato, S., I. Burdett, and R. C. Hughes. 1993. Secretion of the baby hamster kidney 30-kDa galactose-binding lectin from polarized and nonpolarized cells: a pathway independent of the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi complex. Exp. Cell Res. 207:8-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato, S., N. Ouellet, I. Pelletier, M. Simard, A. Rancourt, and M. Bergeron. 2002. Role of galectin-3 as an adhesion molecule for neutrophil extravasation during streptococcal pneumonia. J. Immunol. 168:1813-1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swarte, V. V., R. E. Mebius, D. H. Joziasse, D. H. Van den Eijnden, and G. Kraal. 1998. Lymphocyte triggering via L-selectin leads to enhanced galectin-3-mediated binding to dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:2864-2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villalta, F., Y. Zhang, K. Bibb, J. M. Burns, Jr., and M. F. Lima. 1988. Signal transduction in human macrophages by gp83 ligand of Trypanosoma cruzi: trypomastigote gp83 ligand up-regulates trypanosome entry through the MAP kinase pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 249:247-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villalta, F., C. Smith, A. Ruiz-Ruano, and M. F. Lima. 2001. A ligand that Trypanosoma cruzi uses to bind to mammalian cells to initiate infection. FEBS Lett. 505:383-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villalta, F., Y. Zhang, K. Bibb, S. Pratap, J. M. Burns, Jr., and M. F. Lima. 1999. Signal transduction in human macrophages by gp83 ligand of Trypanosoma cruzi: trypomastigote gp83 ligand up-regulates trypanosome entry through protein kinase C activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. Res. Commun. 2:64-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vray, B., I. Camby, V. Vercruysse, T. Mijatovic, N. V. Bovin, P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, H. Kaltner, and I. Salmon. 2004. Upregulation of galectin-3 and its ligands by Trypanosoma cruzi infection with modulation of adhesion and migration of murine dendritic cells. Glycobiology 7:647-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]