Abstract

Glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), the principal constituent of the Cryptococcus neoformans capsule, modulates the inflammatory response of human monocytes in vitro. Here we examine the efficacy of GXM as a novel anti-inflammatory compound for use against experimental septic arthritis. Arthritis was induced in mice by the intravenous injection of 8 × 106 CFU of type IV group B streptococcus (GBS). GXM was administered intravenously in different doses (50, 100, or 200 μg/mouse) 1 day before and 1 day after bacterial inoculation. GXM treatment markedly decreased the incidence and severity of articular lesions. Histological findings showed limited periarticular inflammation in the joints of GXM-treated mice, confirming the clinical observations. The amelioration of arthritis was associated with a significant reduction in the local production of interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), and MIP-2 and an increase in systemic IL-10 levels. Moreover, peritoneal macrophages derived from GXM-treated mice and stimulated in vitro with heat-inactivated GBS showed a similar pattern of cytokine production. The present study provides evidence for the modulation of the inflammatory response by GXM in vivo and suggests a potential therapeutic use for this compound in pathologies involving inflammatory processes.

Glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) is the principal constituent of the capsular material of Cryptococcus neoformans (7) and exerts many immunoregulatory effects (40). Soluble GXM has numerous biological activities that may contribute to the pathogenesis of infection, and high levels of GXM have been found in sera from patients with cryptococcosis (4). After systemic administration, GXM is retained for an indefinite period in tissues containing mononuclear phagocytes (11, 18, 24), and macrophages serve as a long-term reservoir for GXM storage (13). It was recently demonstrated that GXM is continuously accumulated by macrophages for longer than 1 week in vitro and is retained inside these cells, altering their biological functions (23). The binding and internalization of GXM affect monocyte/macrophage effector and secretory functions. In particular, a secretion of interleukin-10 (IL-10) (41) and an inhibition of the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (42), are observed after in vitro treatment of monocytes/macrophages with GXM. In addition, GXM inhibits the migration of neutrophils in response to IL-8 (19) and delays the translocation of leukocytes across the blood-brain barrier in an animal model of acute bacterial meningitis (20).

Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, group B streptococci (GBS) are still a leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality and are also an emerging public health problem for nonpregnant adults (3, 8, 9, 33). Invasive neonatal GBS infections have either an early (usually the first 24 h after birth) or late (7 days after birth) onset. Common manifestations of GBS disease in neonates include pneumonia, septicemia, meningitis, bacteremia, and bone or joint infection (3). Septic arthritis is one of the clinical manifestations of GBS infection in neonates (3) and is often associated with aging and serious underlying diseases in adults (16, 30, 31, 33). Articular lesions in GBS-infected mice are similar to those observed for human disease, making the mouse an excellent model for studying GBS arthritis (35, 36). Mice inoculated with serotype IV GBS show clinical signs of arthritis that are characterized by an early onset and by evolution from an acute exudative synovitis to permanent lesions with irreversible joint damage and/or ankylosis (36). In this model, the production of proinflammatory cytokines, in particular IL-6 and IL-1β, increases in sera and joints in response to GBS infection, and a direct correlation was observed between IL-6 and IL-1β concentrations in the joints and the severity of arthritis (37). Additional evidence for the detrimental role of proinflammatory cytokines was obtained by use of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. The administration of exogenous IL-10 produced a decrease in pathology that was associated with a significant local reduction in IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α levels (28), while the administration of neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibodies resulted in a deleterious effect. Recently, a pivotal contribution of macrophages to GBS-induced arthritis was demonstrated with monocytopenic mice, which showed a less severe development of arthritis associated with a decrease in IL-1β and IL-6 production in joints (27).

Since GXM displays anti-inflammatory activity, we postulated the possibility that GXM may act as an anti-inflammatory agent in this model of GBS-induced septic arthritis. For the present study, we investigated the effect of this microbial compound on the course of GBS-induced arthritis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Eight-week-old female outbred CD-1 mice were obtained from Charles River Breeding Laboratories (Calco, Italy).

Microorganism.

A type IV GBS reference strain, GBS 1/82, was used throughout the study. For experimental infections, the microorganism was grown overnight at 37°C in Todd-Hewitt broth (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) and then was washed and diluted in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Life Technologies, Milan, Italy). The inoculum size was estimated by observations of turbidity, and viability counts were performed by plating the cells on tryptic soy agar-5% sheep blood agar (blood agar) and then incubating them overnight under anaerobic conditions at 37°C. A bacterial suspension was prepared in RPMI 1640 medium. Mice were inoculated intravenously via the tail vein with 8 × 106 GBS in a volume of 0.5 ml. Control mice were injected by the same route with 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium.

Cryptococcal polysaccharide.

GXM was isolated from the culture supernatant of a serotype A strain of C. neoformans (CN 6) that was grown in liquid synthetic medium (7) in a gyratory shaker for 4 days at 30°C. GXM was isolated by differential precipitation with ethanol and hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) (6). The isolation procedure was described previously in detail (14). GXM was diluted in saline and injected intravenously in a 0.3- ml volume at a dose of 50, 100, or 200 μg/mouse 1 day before and 1 day after GBS infection. Control mice received saline according to the same experimental schedule.

Clinical evaluation of arthritis and mortality.

Mice injected with GBS and treated with GXM or saline as described above were evaluated for clinical signs of arthritis and for mortality. Mortality was recorded at 24-h intervals for 30 days. After the challenge, the mice were examined daily under blinded conditions by two independent observers for 30 days to evaluate the presence of joint inflammation, and scores for arthritis severity (macroscopic scores) were given as previously described (28, 36, 37). Arthritis was defined as visible erythema and/or swelling of at least one joint. The clinical severity of arthritis was graded on a scale of 0 to 3 for each paw, according to changes in erythema and swelling (0 = no change, 1 = mild swelling and/or erythema; 2 = moderate swelling and erythema; 3 = marked swelling, erythema, and/or ankylosis). Thus, each mouse could have a maximum score of 12. The arthritis index (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) was constructed by dividing the total score (cumulative value for all paws) by the number of animals used for each experimental group.

Histological assessment.

Groups of mice infected with GBS and treated with GXM or saline were examined 7 days after infection for histopathological features of arthritis. Arthritic hind paws (one per mouse) were removed aseptically, fixed in 10% (vol/vol) formalin for 24 h, decalcified in 5% (vol/vol) trichloroacetic acid for 7 days, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 3- to 4-μm-thick sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The samples were examined under blinded conditions. Tibia-tarsal, tarsus-metatarsal, and metatarsus-phalangeal joints were examined, and the extents of infiltrate (presence of inflammatory cells in the subcutaneous and/or periarticular tissues), exudate (presence of inflammatory cells in the articular cavity), cartilage damage, bone erosion, and loss of joint architecture were evaluated. The arthritis severity was classified as mild (minimal infiltrate), moderate (presence of infiltrate, minimal exudate, and integrity of joint architecture), or severe (presence of massive infiltrate and/or exudate, cartilage and bone erosion, and disrupted joint architecture).

GBS growth in blood, kidneys, and joints.

Blood, kidney, and joint infections in GBS-infected mice treated with GXM or saline were determined by evaluations of CFU at different times after inoculation. Blood samples were obtained by retro-orbital sinus bleeding before the mice were sacrificed. Tenfold dilutions were prepared in RPMI 1640 medium, and 0.1 ml of each dilution was plated in triplicate on blood agar and incubated under anaerobic conditions for 24 h. The numbers of CFU were determined, and the results were expressed as numbers of CFU per milliliter of blood. Kidneys were aseptically removed and homogenized with 3 ml of sterile RPMI 1640. All wrist and ankle joints from each mouse were removed, weighed, and homogenized in toto in sterile RPMI 1640 medium (1 ml/100 mg of joint weight). After homogenization, all tissue samples were diluted and plated in triplicate on blood agar, and the results were expressed as numbers of CFU per whole organ or per milliliter of joint homogenate.

Sample preparation for cytokine assessment.

Blood samples from the different experimental groups were obtained by retro-orbital sinus bleeding at different times after infection before the mice were sacrificed. Sera were stored at −80°C until analysis. Joint tissues were prepared as previously described (37). Briefly, all wrist and ankle joints from each mouse were removed and then homogenized in toto in 1 ml of lysis medium (RPMI 1640 containing 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and a 1-μg/ml final concentration [each] of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin A)/100 mg of joint weight. The homogenized tissues were then centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant fluids were sterilized through a Millipore filter (0.45-μm pore size) and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 ml of 10% thioglycolate (Sigma) and treated intravenously with GXM (100 μg/mouse) or saline the same day and 2 days after thioglycolate injection. After 3 days, peritoneal exudate cells were harvested by lavage with RPMI 1640 medium. The cells were washed with medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 50 μg of gentamicin/ml (complete medium), counted in a hemocytometer, and plated in 24-well plates (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, N.J.) at a density of 2 × 106/ml. After 2 h, nonadherent cells were removed by washing with medium, and adherent cells were stimulated with heat-inactivated GBS (10 CFU/macrophage) for 6 or 24 h. After culturing, the supernatant fluids were removed and stored at −80°C until they were used for assays.

Cytokine assays.

IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), and MIP-2 concentrations in the biological samples were measured by the use of commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The results were expressed in picograms per milliliter of serum or supernatant from joint homogenates. The detection limits of the assays were 1.6 pg/ml for IL-6, 3 pg/ml for IL-1β, 4 pg/ml for IL-10, 1.5 pg/ml for MIP-1α, and 1.5 pg/ml for MIP-2.

Statistical analysis.

Differences in the arthritis indexes, numbers of CFU, and cytokine concentrations between the groups of mice were analyzed by Student's unpaired t test. The log-rank test was used for paired data analyses of Kaplan-Meier survival curves. The incidence of arthritis was analyzed by Fisher's exact text, and histological data were analyzed by the χ2 test. Each experiment was repeated three times. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P values of <0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of GXM administration on clinical course of arthritis.

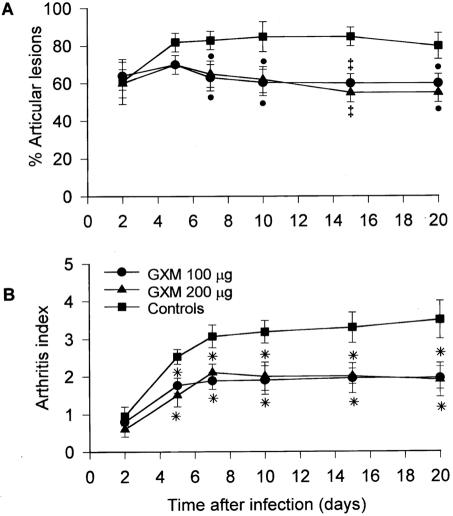

Clinical signs of joint swelling were observed in 35% of the mice as early as 24 h after the injection of 8 × 106 CFU of GBS. The incidence of arthritis increased to 80% by day 5, and 85% of the animals had articular lesions on day 10 after infection (Fig. 1A). Similarly, the arthritis index progressively increased and reached its maximum value 10 days after the GBS challenge (mean value, 3.2 ± 0.3) (Fig. 1B); most of the animals had articular lesions in both the hind paws and front paws. Twenty percent of the mice died during the course of infection. GXM was administered 1 day before and 1 day after infection at a dose of 50, 100, or 200 μg/mouse. Treatment with 100 or 200 μg of GXM resulted in a smaller number of animals with articular lesions than that for controls; differences between GXM-treated mice and controls were significant starting 7 days after infection. Similarly, the arthritis indexes for GXM-treated mice were significantly lower than those for controls from day 5 on, reaching maximum values of 1.9 ± 0.4 and 2.0 ± 0.2 for mice given doses of 100 and 200 μg of GXM, respectively, compared to 3.2 ± 0.3 for controls. The dose of 50 μg had no effect on the incidence or severity of GBS arthritis (data not shown). The survival rates of GXM-treated mice did not differ from those of controls at any dose employed (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of GXM treatment on incidence and severity of arthritis in mice infected with GBS. GXM (100 or 200 μg/mouse) was administered 1 day before and 1 day after infection with 8 × 106 CFU of GBS/mouse. Ten mice were used for each experimental group. (A) Incidence of arthritis. Values represent the means ± SD of three separate experiments, each consisting of 10 animals per experimental group. •, P < 0.05; ‡, P < 0.01 (for GXM-treated versus control mice, according to Fisher's exact test). (B) Arthritis index. Values represent the means ± SD of three separate experiments, each consisting of 10 animals per experimental group. *, P < 0.01 (for GXM-treated versus control mice, according to unpaired Student's t test).

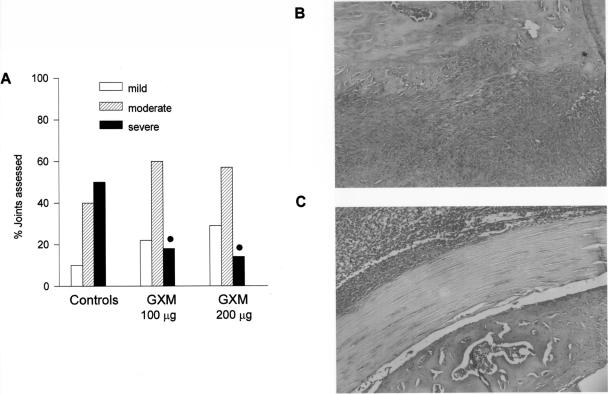

Arthritic hind paws were removed for histologic examination on day 7 after infection. For controls, >50% of the examined joints were classified as severely affected (Fig. 2A), with the presence of a massive periarticular infiltrate and evidence of cartilage degradation (Fig. 2B). In contrast, most of the joints examined from GXM-treated mice were classified as moderately affected (Fig. 2A), with the inflammatory infiltrate limited to subcutaneous and muscular tissues (Fig. 2C). Only 18% (with 100 μg of GXM) and 14% (with 200 μg of GXM) of the joints were classified as severely affected.

FIG. 2.

Histopathological evaluation of GBS-induced arthritis after systemic administration of GXM. (A) Histopathological severity of arthritis (for 100 μg of GXM, 10 paws and 24 joints were assessed; for 200 μg of GXM, 10 paws and 22 joints were assessed; for saline treatment, 10 paws and 28 joints were assessed). •, P < 0.05 (for GXM-treated versus control mice, according to χ2 test). (B) Severe arthritis in a control mouse, with presence of massive infiltrate and evidence of cartilage degradation. (C) Upon GXM treatment, the presence of infiltrate was limited to subcutaneous and muscular tissues, with a maintenance of cartilage integrity (original magnification, ×10).

GBS growth rates were assessed for blood, kidneys, and joints of mice that were treated or not treated with GXM. No significant differences were observed between the experimental groups, regardless of the treatment used (data not shown).

Effect of GXM administration on cytokine production.

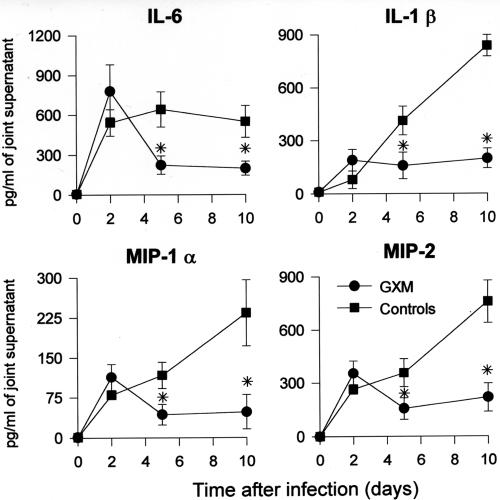

Plasma and joint specimens from mice that were treated with GXM (100 μg) or saline were collected on days 0, 2, 5, and 10 after GBS infection for assessments of cytokine (IL-6 and IL-1β) and chemokine (MIP-1α and MIP-2) production.

A rapid increase in IL-6, IL-1β, MIP-1α, and MIP-2 production was observed for the joints of GBS-treated mice, with sustained levels still present 10 days after infection (Fig. 3). GXM treatment significantly affected these cytokine and chemokine levels. In fact, although similar concentrations of the inflammatory products were present 2 days after infection for the two experimental groups, a marked decrease was observed in the subsequent days for GXM-treated mice. The phenomenon was still evident at the end of the experimental period (Fig. 3). A down-regulation in the production of IL-6 and IL-1β following GXM treatment was also observed for systemic levels in the first week after infection (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Effect of GXM treatment on cytokine and chemokine production in joints of GBS-infected mice. Mice were treated with GXM (100 μg/mouse) 1 day before and 1 day after infection with 8 × 106 CFU of GBS/mouse. Day 0 represents uninfected mice. Data represent the means ± SD of three separate experiments. Three mice per group were sacrificed at each indicated time point. *, P < 0.01 (for GXM-treated versus control mice, according to unpaired Student's t test).

Since members of our laboratory recently pointed out a beneficial role of IL-10 in GBS arthritis (28), we also studied the effect of GXM administration on IL-10 production. As shown in Table 1, a dramatic increase in the systemic IL-10 concentration was evident for GXM-treated mice 2 days after infection. Although a gradual decrease in IL-10 levels in sera was observed in the subsequent days, significant differences were still evident between treated and untreated mice on day 10. In contrast, GXM treatment did not affect IL-10 levels in the joints, for which similar IL-10 levels were observed for the two experimental groups.

TABLE 1.

Effect of GXM treatment on systemic and local IL-10 production in GBS-infected micea

| Tissue | Treatment | IL-10 production (pg/ml) on indicated day after infection

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Serum | Saline | 22 ± 5 | 310 ± 50 | 280 ± 54 | 26 ± 8 |

| GXM | 25 ± 6 | 1,600 ± 230b | 460 ± 91b | 150 ± 12b | |

| Joints | Saline | 12 ± 3 | 56 ± 13 | 58 ± 10 | 55 ± 6 |

| GXM | 13 ± 2 | 53 ± 12 | 57 ± 10 | 51 ± 8 | |

Mice were treated with GXM (100 μg/mouse) or saline 1 day before and 1 day after infection with 8 × 106 GBS/mouse. Uninfected mice (day 0) received GXM or saline 1 day before infection. At the indicated times, three mice per experimental group were sacrificed. Values represent the means ± SD from three separate experiments.

P < 0.01 (for GXM-treated versus control mice, according to unpaired Student's t test).

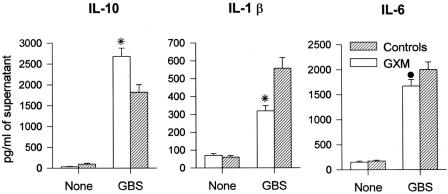

To further confirm the effect of GXM treatment on cytokine production, we performed in vitro experiments with peritoneal macrophages from GXM-treated or naive mice. GXM (100 μg/mouse) or saline was administered the same day and 2 days after thioglycolate injection. The cells were stimulated with heat-inactivated GBS (10 GBS/cell) for 6 or 24 h, and cell culture supernatant fluids were assessed for IL-10, IL-1β, and IL-6 production. As shown in Fig. 4, the in vivo GXM treatment significantly enhanced IL-10 production by peritoneal macrophages in response to GBS after 24 h of stimulation. Conversely, a significant inhibition of IL-1β and IL-6 secretion was observed under the same culture conditions. Similar results were obtained for a stimulation time of 6 h (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cytokine and chemokine production from peritoneal macrophages derived from GXM-treated mice and stimulated in vitro with GBS. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 ml of 10% thioglycolate and then treated with GXM (100 μg/mouse) or saline the same day and 2 days after thioglycolate injection. Peritoneal macrophages were then recovered and stimulated as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the means ± SD of three separate experiments. •, P < 0.05; *, P < 0.01 (for GXM-treated versus control mice, according to unpaired Student's t test).

DISCUSSION

The present paper documents the potential therapeutic benefits of GXM in an experimental model of septic arthritis. This experimental model was chosen based on the rapid progression and highly destructive joint disease induced by GBS (35). GXM treatment markedly decreased the incidence of arthritis. Moreover, it resulted in a smaller number of articular lesions that were classified as severely affected. Finally, low levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines were present in the joints of GXM-treated mice.

In vitro studies have found that the capsular polysaccharide of C. neoformans suppresses a variety of cellular functions (40). Here we demonstrated the ability of GXM to modulate inflammatory responses in an in vivo system of bacterial infection. In the first 2 days after GBS infection, the progress of the disease was similar regardless of GXM treatment; however, a beneficial effect of GXM administration became apparent with increasing times after infection. This differential effect of GXM on the early versus late development of joint lesions suggests that GXM, although it is unable to prevent the onset of arthritis, efficiently acts on the progression of the disease by hampering the worsening of articular lesions. Similar effects were observed by Mirshafiey et al., who used a culture filtrate of C. neoformans var. gatti with a rat model of Staphylococcus aureus-induced arthritis (21).

The beneficial effect of GXM was confirmed by histopathological studies. A fivefold reduction in the number of lesions that were classified as severely affected was observed for GXM-treated mice. In addition, a limited cellular influx of inflammatory cells was present in the joints of treated animals, likely due to the decreased production of MIP-1α and MIP-2 at the joint level. These data are in agreement with previous studies showing the abilities of GXM to limit chemotaxis (19, 20) and to suppress the expression of a chemotactic receptor such as C5aR on inflammatory cells (22). The facts that no effect was observed with 50 μg of GXM and that similar therapeutic effects were observed with 100 and 200 μg of GXM are consistent with the results of earlier in vitro studies (23) and suggest a sharp dose-response curve. In vitro experiments showed that the loading of GXM in macrophages and neutrophils occurred at doses of 50 to 100 μg/ml; higher doses (200 μg/ml) did not augment GXM internalization, suggesting a cell saturation or threshold effect (23). Thus, it is conceivable that the in vivo inoculation of 50 μg of GXM did not result in any effects because this concentration was not sufficient to produce the monocyte/macrophage saturation that is required to affect their functions. Conversely, the inoculation of 100 or 200 μg of GXM induced maximal loading, resulting in no significant differences between the two doses.

The clinical benefit mediated by GXM was accompanied by a marked reduction in local IL-6 and IL-1β production. Both cytokines are known to contribute directly to articular damage. IL-1β, together with TNF-α, induces the release of tissue-damaging enzymes from synovial cells and articular chondrocytes and activates osteoclasts (2, 38). IL-6 participates with IL-1 in the catabolism of connective tissue components at inflammation sites (15, 25) and activates osteoclasts, resulting in joint destruction (12). GXM treatment also resulted in a strong increase in the IL-10 concentration in the sera of GBS-challenged mice, although we failed to detect a GXM effect on IL-10 production in the joints. This may have been due to a prompt reutilization of locally produced IL-10 or, alternatively, to a lack of susceptibility of local cells such as synoviocytes, which are known to produce IL-10 (29), to GXM. In vitro experiments confirmed the in vivo results, since peritoneal macrophages from GXM-treated mice produced remarkably less IL-1β and IL-6 upon GBS stimulation in vitro, while increased IL-10 production was observed. It is noteworthy that the observed modification in local and systemic cytokine and chemokine production was not dependent on the number of microorganisms, since similar bacterial loads were present in the GXM-treated and untreated mice.

In this study, the anti-inflammatory effect of GXM was evident starting 2 days after infection. Keeping in mind that GXM accumulates in macrophages (23) and that this cell population reaches the joints 2 to 3 days after infection in bacterial arthritis (5, 10, 26), our results suggest that the beneficial effects observed at the local level are mediated by GXM-loaded macrophages. Indeed, GXM does not prevent the induction of inflammatory cytokines or chemokines, but rather limits their production, thus restraining pathological processes.

Cryptococcal lesions are often characterized by the absence of an inflammatory response, which is mainly attributable to the negative signals provided by GXM during cryptococcosis (40). Although inflammation is an essential component of the host defense against infections, nonetheless an excessive inflammatory response can lead to a detrimental outcome, such as arthritis. Here we demonstrated that the negative properties of GXM may become positive for other pathologies. In conclusion, this study provides evidence for a beneficial effect of GXM in septic arthritis. Its effect is likely due to the ability of GXM to modulate macrophage activities, thus limiting local proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production and leukocyte recruitment. The advantages of this product, in contrast with others that have been proposed for arthritis therapy, such as cytokines or specific antibodies, are that GXM is readily produced in large amounts, has extended pharmacokinetics, and shows no overt signs of toxicity in vivo. The dose and timing of GXM administration used for this study seemed to be effective without producing side effects. Based on the detrimental role of macrophages (27, 39, 43) and proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in septic and aseptic chronic disease (1, 17, 25, 32, 34, 37), our results raise the possibility of the therapeutic use of GXM to cure or prevent articular pathologies induced by inflammatory processes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica, Italy, 2003-2004, Prot. 2003068044_005 and Prot. 2003068044_006, and by Public Health Service grant AI14209 from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank Maurizio Marangi for graphic support, Jo-Anne Rowe for dedicated editorial assistance, and Alessandro Braganti and Stefano Temperoni for their excellent technical assistance in histological processing and animal care.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Arend, W. P., and J. M. Dayer. 1990. Cytokines and cytokine inhibitors or antagonists in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 33:305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arend, W. P., and J. M. Dayer. 1995. Inhibition of the production and effects of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor α in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 38:151-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, C. J., and M. S. Edwards. 1995. Group B streptococcal infections, p. 980-1054. In J. S. Remington and J. O. Klein (ed.), Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, 4th ed. W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 4.Bennett, J. E., H. F. Hasenclaver, and B. S. Tynes. 1964. Detection of cryptococcal polysaccharide in serum and spinal fluid: value in diagnosis and prognosis. Trans. Assoc. Am. Physician 77:145-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bremmel, T., A. Abdelnour, and A. Tarkowski. 1992. Histopathological and serological progression of experimental Staphylococcus aureus arthritis. Infect. Immun. 60:2976-2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherniak, R., E. Reiss, M. E. Slodki, R. D. Plattner, and S. O. Blumer. 1980. Structure and antigenic activity of the capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A. Mol. Immunol. 17:1025-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherniak, R., and J. B. Sundstrom. 1994. Polysaccharide antigens of the capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 62:1507-1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper, B. W., and E. Morganelli. 1998. Group B streptococcal bacteremia in adults at Hartford Hospital 1991-1996. Conn. Med. 62:515-517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardam, M. A., D. E. Low, R. Saginur, and M. A. Miller. 1998. Group B streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome in adults. Arch. Intern. Med. 158:1704-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenberg, D. L., and J. L. Reed. 1985. Bacterial arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 312:764-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman, D. L., S. C. Lee, and A. Casadevall. 1995. Tissue localization of Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan in the presence and absence of specific antibody. Infect. Immun. 63:3448-3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green, J., S. Scotland, Z. Sella, and C. R. Kleeman. 1994. Interleukin-6 attenuates agonist-mediated calcium mobilization in murine osteoblastic cells. J. Clin. Investig. 93:2340-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grinsell, M., L. C. Weinhold, J. E. Cutler, Y. Han, and T. R. Kozel. 2001. In vivo clearance of glucuronoxylomannan, the major capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans: a critical role for tissue macrophages. J. Infect. Dis. 84:479-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houpt, D. C., G. S. Pfrommer, B. J. Young, T. A. Larson, and T. R. Kozel. 1994. Occurrences, immunoglobulin classes and biological activities of antibodies in normal human serum that are reactive with Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan. Infect. Immun. 62:2857-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito, A., Y. Itoh, Y. Sasaguri, M. Morimatsu, and Y. Mori. 1992. Effects of interleukin-6 on the metabolism of the connective tissue components in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 35:1197-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson, L. A., R. Hilsdon, M. M. Farley, H. Harrison, A. L. Reingold, B. D. Plikatis, D. Wenger, and A. Schuchat. 1995. Risk factors for group B streptococcal disease in adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 123:415-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasama, T., R. M. Strieter, N. W. Lukacs, P. M. Lincoln, M. D. Burdick, and S. L. Kunkel. 1995. Interleukin-10 expression and chemokine regulation during the evolution of the murine type II collagen-induced arthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 95:2868-2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lendvai, N., A. Casadevall, Z. Liang, D. L. Goldman, J. Makherjee, and L. S. Zuckier. 1998. Effect of immune mechanisms on the pharmacokinetics and organ dissemination of cryptococcal polysaccharide. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1647-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipovsky, M. M., G. Gekker, S. Hu, L. C. Ehrlich, A. I. Hoepelman, and P. K. Peterson. 1998. Cryptococcal glucuronoxylomannan induces interleukin (IL)-8 production by human microglia but inhibits neutrophil migration toward IL-8. J. Infect. Dis. 177:260-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipovsky, M. M., L. Tsenova, F. E. Coenjaerts, G. Kaplan, R. Cherniak, and A. I. Hoepelman. 2000. Cryptococcal glucuronoxylomannan delays translocation of leukocytes across the blood-brain barrier in an animal model of acute bacterial meningitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 11:10-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirshafiey, A., M. Chitsaz, M. Attar, F. Mehrabian, and A. R. Razavi. 2000. Culture filtrate of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gatti (CneF) as a novel anti-inflammatory compound in the treatment of experimental septic arthritis. Scand. J. Immunol. 52:278-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monari, C., T. R. Kozel, F. Bistoni, and A. Vecchiarelli. 2002. Modulation of C5aR expression on human neutrophils by encapsulated and acapsular Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 70:3363-3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monari, C., C. Retini, A. Casadevall, D. Netski, F. Bistoni, T. R. Kozel, and A. L. Vecchiarelli. 2003. Differences in the outcome of the interaction between Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan and human monocytes and neutrophils. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:1041-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muchmore, H. G., E. N. Scott, and R. A. Fromtling. 1982. Cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide clearance in non immune mice. Mycopathologia 78:41-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nietfeld, J. J., B. Wilbrink, M. Helle, J. L. A. M. van Roy, W. den Otter, A. J. G. Swank, and O. Huber-Bruning. 1990. Interleukin-1-induced interleukin-6 is required for the inhibition of proteoglycan synthesis by interleukin-1 in human articular cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 33:1695-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters, K. M., K. Goberg, T. Rosendahl, B. Klosterhalfen, A. Straub, and G. Zwaldo-Klarwasser. 1996. Macrophage reaction in septic arthritis. Arch. Ortop. Trauma Surg. 115:347-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puliti, M., C. von Hunolstein, F. Bistoni, R. Castronari, G. Orefici, and L. Tissi. 2002. Role of macrophages in experimental group B streptococcal arthritis. Cell. Microbiol. 4:691-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puliti, M., C. von Hunolstein, F. Bistoni, C. Verwaerde, G. Orefici, and L. Tissi. 2002. Regulatory role of interleukin-10 in experimental group B streptococcal arthritis. Infect. Immun. 70:2862-2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritchilin, C., and S. A. Haas-Smith. 2001. Expression of interleukin 10 mRNA and protein by synovial fibroblastoid cells. J. Rheumatol. 28:698-705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schattner, A., and K. L. Vosti. 1998. Recurrent group B streptococcal arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 17:387-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schattner, A., and K. L. Vosti. 1998. Bacterial arthritis due to beta-hemolytic streptococci of serogroups A, B, C, F, and G. Analysis of 23 cases and a review for literature. Medicine 77:122-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrier, D. J., R. C. Schimmer, C. M. Flory, D. K. Tung, and P. A. Ward. 1998. Role of chemokines and cytokines in a reactivation model of arthritis in rats induced by injection with streptococcal cell walls. J. Leukoc. Biol. 63:359-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straus, C., D. Caplanne, A. M. Bergemer, and J. M. le Parc. 1997. Destructive polyarthritis due to a group B streptococcus. Rev. Rheum. Engl. 64:339-341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thornton, S., N. E. Duwel, G. P. Boivin, Y. Ma, and R. Hirsch. 1999. Association of the course of collagen-induced arthritis with distinct patterns of cytokine and chemokine messenger RNA expression. Arthritis Rheum. 42:1109-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tissi, L. 1999. Experimental group B Streptococcus arthritis in mice, p. 549-559. In O. Zak and M. Sande (ed.), Handbook of animal models of infection. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 36.Tissi, L., P. Marconi, P. Mosci, L. Merletti, P. Cornacchione, E. Rosati, S. Recchia, C. von Hunolstein, and G. Orefici. 1990. Experimental model of type IV Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus) infection in mice with early development of septic arthritis. Infect. Immun. 58:3093-3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tissi, L., M. Puliti, R. Barluzzi, G. Orefici, C. von Hunolstein, and F. Bistoni. 1999. Role of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6 in a mouse model of group B streptococcal arthritis. Infect. Immun. 67:4545-4550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van de Loo, F. A. J., L. A. B. Joosten, P. L. E. M. van Lent, O. J. Arntz, and W. B. van den Berg. 1995. Role of interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and interleukin-6 in cartilage proteoglycan metabolism and destruction. Arthritis Rheum. 38:164-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van den Berg, W., and P. L. van Lent. 1996. The role of macrophages in chronic arthritis. Immunobiology 195:614-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vecchiarelli, A. 2000. Immunoregulation by capsular components of Cryptococcus neoformans. Med. Mycol. 38:407-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vecchiarelli, A., C. Retini, C. Monari, C. Tascini, F. Bistoni, and T. R. Kozel. 1996. Purified capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans induces interleukin-10 secretion by human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 64:2846-2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vecchiarelli, A., C. Retini, D. Pietrella, C. Monari, C. Tascini, T. Beccari, and T. R. Kozel. 1995. Downregulation by cryptococcal polysaccharide of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1β secretion from human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 63:2919-2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verdrengh, M., and A. Tarkowski. 2000. Role of macrophages in Staphylococcus aureus-induced arthritis and sepsis. Arthritis Rheum. 43:2276-2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]