Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease pathogen, cycles between its Ixodes tick vector and vertebrate hosts, adapting to vastly different biochemical environments. Spirochete gene expression as a function of temperature, pH, growth phase, and host milieu is well studied, and recent work suggests that regulatory networks are involved. Here, we examine the release of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 proteins into conditioned medium. Spirochetes intrinsically radiolabeled at concentrations ranging from 107 to 109 cells per ml secreted Oms28, a previously characterized outer membrane porin, into RPMI medium. As determined by immunoblotting, this secretion was not associated with outer membrane blebs or cytoplasmic contamination. A similar profile of secreted proteins was obtained for spirochetes radiolabeled in mixtures of RPMI medium and serum-free Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK II) medium. Proteomic liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of tryptic fragments derived from strain B31 culture supernatants confirmed the identity of the 28-kDa species as Oms28 and revealed a 26-kDa protein as 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase (Pfs-2), previously described as Bgp, a glycosaminoglycan-binding protein. The release of Oms28 into the culture medium is more selective when the spirochetes are in logarithmic phase of growth compared to organisms obtained from stationary phase. As determined by immunoblotting, stationary-phase spirochetes released OspA, OspB, and flagellin. Oms28 secreted by strains B31, HB19, and N40 was also recovered by radioimmunoprecipitation. This is the first report of B. burgdorferi protein secretion into the extracellular environment. The possible roles of Oms28 and Bgp in the host-pathogen interaction are considered.

Lyme disease, caused by at least three species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, is the most prevalent vector-borne disease in the United States (56). Acute symptoms are flu-like, including headache, fever, myalgia, and fatigue, often accompanied by a distinct, ring-shaped erythema migrans rash at the bite site. The chronic phase is characterized by persistent arthritis and neurological compromise and may be associated with cardiac complications (49).

Gene regulation and the synthesis of B. burgdorferi proteins in response to the natural cycling between Ixodes species vectors and vertebrate hosts have been investigated on the global level with DNA microarrays (5, 37, 38). The manipulation of in vitro culture conditions approximating the host environment has revealed regulatory networks and patterns of protein expression relevant to the host-pathogen interaction (1, 7, 23-25, 43, 44, 51). Some findings suggest that the onset of stationary phase in the tick and the accompanying slowing of replication in response to an altered biochemical environment may be related to cell density-dependent signaling. Under in vitro conditions, lipoproteins P35 and P7.5 are upregulated at the onset of stationary phase (43), and a broader investigation identified the growth phase-dependent expression of 13 additional proteins (44). Following infection, B. burgdorferi also induces proteins that facilitate interaction with host proteins, cells, or tissues (10, 18, 31). OspE family proteins protect the spirochete by binding to factor H, which inhibits complement activation, therefore interfering with the innate immune response (22, 27, 28, 34, 35). More fundamentally, the spirochete can also modify its plasmid profile when changing hosts (47), with a resultant alteration in de novo purine synthesis (32).

An unresolved issue regarding the response of B. burgdorferi to its changing environment is that of quorum sensing mediated by autoinducer 2 (AI-2). AI-2 synthase, encoded by the luxS gene, was first discovered in Vibrio harveyi, and luxS homologues are known in a number of bacteria, including B. burgdorferi (16, 17, 36, 37, 50). The functionality of the B. burgdorferi luxS homologue was confirmed by demonstrating that conditioned medium derived from Escherichia coli DH5α transformants harboring borrelial luxS signals differential protein expression in the spirochete (57). Moreover, B. burgdorferi preferentially expresses its luxS gene and a sensory transduction histidine kinase while resident in the gut of engorging ticks (37). However, other findings indicate that B. burgdorferi does not need a functional LuxS/AI-2 system gene to infect mice by intradermal needle inoculation and that it is not essential for adaptation and survival in mammals (24).

The secretion of proteins into the extracellular environment is a common feature of microbial pathogens, and while outer membrane-associated proteins of B. burgdorferi have been studied extensively, exoprotein release by the spirochete has not been reported. B. burgdorferi contains homologues of the essential sec proteins of the general secretory pathway, which is thought to be the mechanism for lipoprotein transport to the outer membrane (17). Related spirochetes secrete proteins into the extracellular environment. Leptospira interrogans exports SphH, a pore-forming hemolysin that is cytotoxic to mammalian cells (30), and the major surface protein (Msp) of Treponema denticola is a pore-forming cytolysin with hemolytic activity (14).

Since B. burgdorferi responds to changes in the host environment, we investigated whether the spirochete is capable of extracellular protein secretion and if the release of proteins into conditioned medium is influenced by the growth phase. The presence of the borrelial porin Oms28 and the 26-kDa glycosaminoglycan-binding protein Bgp in RPMI conditioned medium was determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) microsequencing. Oms28 secretion as a function of spirochete growth phase was also monitored by intrinsic radiolabeling and immunochemistry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

B. burgdorferi low-passage strains B31, N40, and HB19 were provided by Steven Barthold (University of California, Davis). Strain B313 is OspA and -B deficient and was kindly provided by Jorge Benach (State University of New York, Stony Brook, N.Y.). Spirochetes were maintained in either BSK II medium (2) containing 6% (vol/vol) rabbit serum or in a serum-free modification that contained 26 μM cholesterol, 12 μM palmitic acid, 12 μM oleic acid, and bovine serum albumin (Fraction V; Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.) at 2.5% (wt/vol). Lipids were delivered as an ethanolic solution at a final concentration of 0.1% (vol/vol). Spirochete density at harvest was determined using dark-field microscopy and a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber.

Intrinsic radiolabeling experiments.

B. burgdorferi strains passaged in the laboratory fewer than 10 times at 34°C were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min, washed once gently with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and recovered by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min. The washed spirochete pellet was resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium (pH 7.5) (Sigma Chemical Co.) lacking cysteine and methionine. For intrinsic labeling, 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine (Trans label; Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, Mass.) was added at concentrations ranging from 250 to 800 μCi/ml (depending on the experiment), and the spirochetes were incubated at 34°C for 30 to 180 min. Following labeling, the spirochetes were recovered by centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 × g. The conditioned medium was removed and centrifuged again in the same manner. Most conditioned medium samples were concentrated by ultrafiltration (Centricon YM-3; Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) and either used immediately or stored at −20°C. Conditioned RPMI medium and whole spirochetes were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Bio-Rad), and exposed to XAR-5 photographic film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, N.Y.). Intrinsic radiolabeling experiments and experiments involving detection of borrelia proteins by immunoblotting with specific antiserum were conducted a minimum of three times.

The effect of growth phase on protein induction and secretion was examined by harvesting spirochetes at the mid-logarithmic, late-logarithmic, and stationary phases of growth (5 × 107 to 1 × 108 cells per ml). Spirochetes were resuspended, concentrated approximately 25-fold in RPMI-1640 medium, and radiolabeled for 60, 120, and 180 min.

SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, and RIP.

Borrelia samples were resolved by discontinuous SDS-PAGE as described by Laemmli (29). Whole spirochetes and conditioned media were examined by immunoblotting and radioimmunoprecipitation (RIP) for specific borrelia proteins. Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane at 100 mA for 3.5 to 4.5 h as described previously (8). Protein transfer was confirmed by reversible Coomassie staining, prestained molecular mass markers (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.), or with radiolabeled proteins by autoradiography after abatement of the chemiluminescent signal. Most immunoblots employed 5 × 107 to 1 × 108 whole spirochetes, and the conditioned medium corresponding to 1 × 108 to 2 × 108 spirochetes. Membranes were processed according to the Western-Light Plus chemiluminescent detection system (Tropix, Bedford, Mass.) and probed for 1 h with a 1:5,000 dilution of mouse monoclonal antibodies to OspA (H5332) and OspB (H6831) (obtained from Alan Barbour, University of California, Irvine). A goat antimouse alkaline phosphatase conjugate secondary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:15,000.

A rabbit antiserum specific for Oms28 (kindly provided by Jonathan Skare, Texas A&M University, College Station, Tex.) was used at a dilution of 1:5,000. Immunoblots with α-Oms28 were carried out according to the Amersham ECL system (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) with the donkey antirabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate used at a dilution of 1:5,000. For RIP of conditioned RPMI medium, spirochetes were radiolabeled at 5 × 108 cells per ml with 35S Trans label at 500 uCi/ml for 90 min at 34°C. Whole spirochetes and conditioned medium were processed as described above. Fifty microliters of conditioned medium was reacted with 2 μl of antiserum overnight at 4°C. Antigen-antibody complexes were recovered with protein A-agarose beads (Sigma), washed according to established protocols (21), and resolved by SDS-PAGE.

Monoclonal antiserum directed against the B. burgdorferi DnaK homologue was provided by Michael Kramer (LA-3) and was used at a dilution of 1:50. A mouse polyclonal antibody against Bgp was a generous gift from Nikhat Parveen (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Mass.) and used at a dilution of 1:2,000. A monoclonal antiserum against OspC (33) was provided by Robert Gilmore (Centers for Disease Control, Fort Collins, Colo.), and antiflagellin (H9724), originally produced by Alan Barbour (3), was kindly provided by Brian Stevenson (University of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky.).

Protein sequencing by LC-MS/MS.

B. burgdorferi strain B31 was harvested at a cell density of 6 × 107 spirochetes per ml, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in RPMI medium to 6 × 109 spirochetes per ml. Conditioned culture medium from the equivalent of 2 × 109 spirochetes was resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Two protein bands, at approximately 26 and 28 kDa, were extracted from the gel, washed with 50% high-performance liquid chromatography-grade acetonitrile in water, digested with trypsin, and microsequenced by high performance liquid chromatography coupled to an LCQ DECA ion-trap mass spectrometer (Finnegan) equipped with a nanospray source (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, Calif.). Sequencing was carried out at the Tufts University Analytical Core Facility (Boston, Mass.). Peptide fragments were evaluated using the Sequest database search program.

RESULTS

Intrinsic radiolabeling and the secretion of B. burgdorferi proteins.

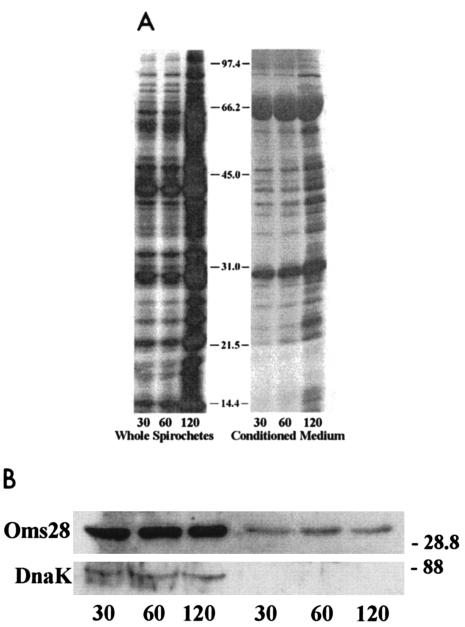

To determine if B. burgdorferi secretes extracellular proteins, strain B31 was cultivated in BSK-II medium, transferred to protein-free RPMI medium, and intrinsically labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine. Spirochetes were initially grown to mid- logarithmic phase (4 × 107 spirochetes per ml), washed gently with PBS, and radiolabeled at a density of 109 spirochetes per ml. Several borrelial proteins accumulated in the conditioned medium during the course of the labeling period, with the most prominent band at approximately 28 kDa (Fig. 1). Additional polypeptides appeared over time. The diffuse band at 66 kDa represents bovine serum albumin carryover from the BSK II medium and its reactivity with the Trans label. Similar radiolabeling experiments with spirochetes harvested at densities approaching 108 cells per ml released a similar profile of proteins into conditioned RPMI medium.

FIG. 1.

B. burgdorferi strain B31 secretes proteins over time, including Oms28. Spirochetes were cultivated to a density of 6 × 107 spirochetes per ml, washed with PBS, resuspended in modified RPMI-1640 medium, and radiolabeled at a density of 109 spirochetes per ml with 250 uCi of 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine/ml for 30, 60, and 120 min. Whole-cell lysates and conditioned medium were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% acrylamide) and visualized by autoradiography. Whole-cell lysates represent 108 spirochetes, with CM from the equivalent of 2 × 108 spirochetes. A. The conditioned medium lanes were exposed to film three times longer than the whole-cell lysates. Molecular masses of protein standards appear in kilodaltons. B. Immunoblot of B. burgdorferi prepared as described above identifies the major band at 28 kDa as Oms28. Whole-cell lysates are to the left, and conditioned medium is to the right.

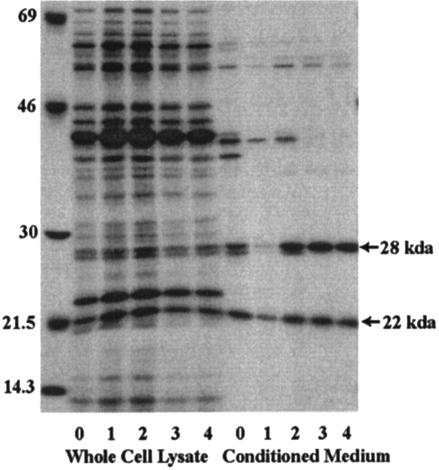

A series of pulse-chase experiments were conducted with the B31 type strain to better assess the dynamics of B. burgdorferi protein secretion. Following harvest, spirochetes were radiolabeled in RPMI medium at 34°C for 2 h. The cells were recovered by centrifugation, resuspended in RPMI medium without label, aliquoted, and incubated for up to 4 h. As seen in Fig. 1, a strong protein band is evident at 28 kDa, and this band persists throughout the chase (Fig. 2). A neighboring band at about 27 kDa was evident in the medium immediately after resuspension in RPMI but was not evident at 3 or 4 h. Additional minor proteins either were lost during the chase or were constitutively present over time. In comparison, a 22-kDa protein present immediately following resuspension of radiolabeled spirochetes in RPMI medium was detected in conditioned medium at roughly the same level throughout the chase.

FIG. 2.

Pulse chase of secreted proteins by strain B31 reveals that Oms28 is released with time and maintained in conditioned medium. Spirochetes were harvested from BSK II medium containing rabbit serum at a density of 3 × 107 cells per ml and were labeled at 34°C for 2 h and chased in cold RPMI medium for the number of hours indicated. Molecular mass markers are shown on the right in kilodaltons.

Identification of Oms28 and Bgp (Pfs-2) as B. burgdorferi secretion products.

Conditioned RPMI medium obtained from 2 × 109 spirochetes was concentrated and resolved by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Two bands at 28 and 26 kDa were extracted from the gel and digested with trypsin, and the peptide sequences were determined by nanospray LC/MS/MS. Oms28, a previously characterized outer membrane porin (54), was identified in the upper band with 41.2% of the amino acid sequence detected (data not shown). The 26-kDa band was identified from the genomic database as Pfs-2, a 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase, with 40.0% of the sequence detected (data not shown). Pfs-2 is more commonly known as Bgp (41), one of several glycosaminoglycan-binding proteins produced by the spirochete (9, 19, 20). Secretion of this GAG-binding protein was confirmed from another preparation of conditioned RPMI medium with 57% of the protein sequence determined (data not shown).

To confirm the identity of Oms28, a polyclonal antiserum was used to detect a band at 28 kDa that was recognized from both whole cells and conditioned medium (Fig. 1B). A monoclonal antiserum against DnaK did not recognize this cytoplasmic marker in the conditioned medium.

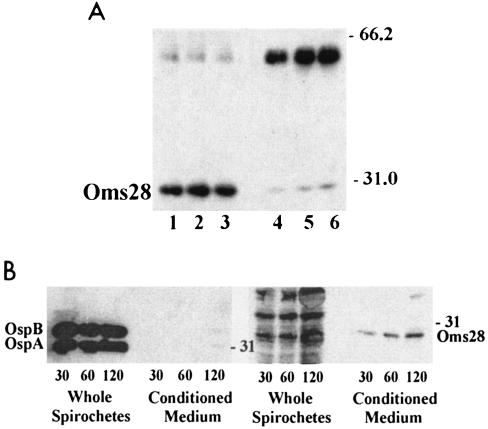

B. burgdorferi releases outer membrane vesicles (OMV) and membrane blebs (58), particularly under stressful conditions, such as metabolic depletion and changes in pH. OMV are known to contain OspA and -B (13), as well as Oms28 (52), and so the extracellular secretion of Oms28 and Bgp could be coincident with the release of OMV. We therefore used monoclonal antisera directed against outer membrane proteins OspA and -B in an immunoblot analysis as markers for OMV. Radiolabeled whole spirochete and conditioned medium fractions were prepared and resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and probed. As determined by immunoblotting, Oms28 was present in both whole spirochetes and conditioned medium (Fig. 3A). While OspA and -B were prominently detected in 108 whole spirochetes, these outer membrane proteins were only barely detectable in the 2-h sample of conditioned RPMI medium from the equivalent of 2 × 108 spirochetes (Fig. 3B, left panel). An autoradiograph of the membrane after abatement of the chemiluminescent signal confirmed the efficient transfer of spirochete proteins (Fig. 3B, right panel) and that the major secreted protein has an apparent molecular mass less than that of OspB or -A. Taken together with the results shown in Fig. 1B, these findings suggest that the extracellular secretion of Oms28 does not appear to be a primary consequence of OMV release or cell lysis.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot of B. burgdorferi B31 whole-cell lysates and conditioned RPMI medium confirms that the major secretory product is Oms28 and that secretion is not associated with outer membrane blebs. A. Samples were transferred to PVDF membrane and probed with polyclonal antibody specific for Oms28. Whole-cell lysates of 107 spirochetes and lanes containing conditioned medium were derived from 5 × 107 cells. Lanes 1 to 3: whole-cell lysates from spirochetes incubated for 30, 60, and 120 min, respectively. Lanes 4 to 6: conditioned medium from spirochetes incubated for 30, 60, and 120 min, respectively. Control incubations identified the strong signal at 50 to 55 kDa in the conditioned medium as the recognition of rabbit immunoglobulin G heavy chain by the donkey antirabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (data not shown). B. The left panel shows 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine whole-cell lysate and conditioned medium samples after 30, 60, or 120 min in RPMI medium that were resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto a PVDF membrane, and probed with monoclonal antibodies specific for OspA and -B. The right panel is an autoradiograph of the PVDF membrane from panel A, exposed to film following the abatement of chemiluminesence.

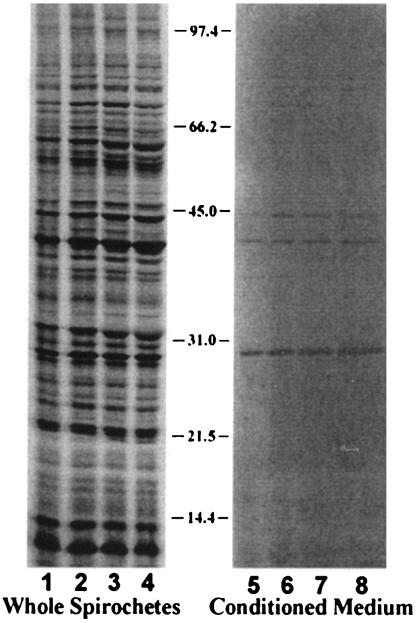

Spirochetes intrinsically labeled in BSK II medium and in BSK II medium diluted with RPMI medium yielded the same pattern of proteins in conditioned medium (Fig. 4), providing support that these extracellular proteins are not primarily released due to cell lysis or osmotic shock.

FIG. 4.

B. burgdorferi protein secretion into BSK II medium lacking serum and bovine serum albumin. Spirochetes harvested at a density of 7 × 107 cells per ml were radiolabeled at 35°C with 500 uCi of 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine/ml for 90 min in RPMI medium and in BSK II medium lacking serum and bovine serum albumin. Lanes 1 to 4 contain 2.4 × 106 cpm of whole spirochetes. Lanes 5 to 8 contain the conditioned medium equivalent to the corresponding whole-cell protein. Radiolabeled proteins shown in lanes 1 and 5 were derived from RPMI medium alone, those in lanes 2 and 6 were derived from 90% RPMI and 10% BSK II, those in lanes 3 and 7 were derived from 50% RPMI and BSK II, and those in lanes 4 and 8 were derived from BSK II alone. Molecular mass markers are shown in kilodaltons.

Effect of growth phase on protein secretion and induction.

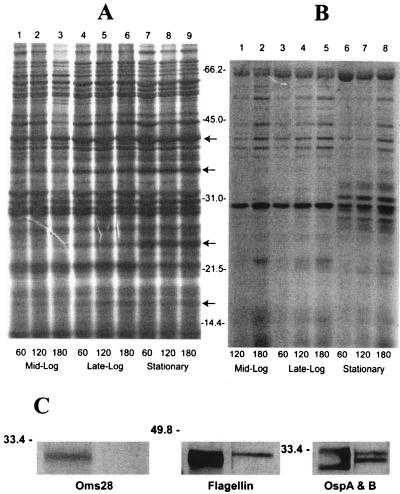

Several studies have demonstrated that B. burgdorferi expresses proteins differentially during growth in culture (25, 44), so it was important to investigate whether the physiological state of the spirochetes affects extracellular protein secretion. A series of experiments were performed, with the results of a single experiment shown in Fig. 5. Strain B31 cultures were harvested at different growth phases, resuspended to 1 × 109 to 2 × 109 spirochetes per ml in RPMI medium, and radiolabeled. As shown, B. burgdorferi selectively secretes Oms28 when spirochetes are in the mid- to late-logarithmic phase of growth (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 5). In contrast, the protein profile of the conditioned medium from stationary-phase cells contains a series of proteins between 25 and 35 kDa and considerably less Oms28. Also, a protein of 23 to 24 kDa seen following labeling of the mid- to late-logarithmic-phase spirochetes for 120 and 180 min is absent when the cells progress to stationary phase. The protein profiles of the whole-cell lysates (Fig. 5A) show that proteins of 42, 34, 24, and 17 kDa increase during stationary phase, in agreement with earlier findings (44). Immunoblot analysis of whole spirochetes and conditioned medium derived from stationary-phase cells demonstrated the presence of flagellin, OspA, and OspB in the conditioned medium, while Oms28 was not detected (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Extracellular protein release is affected by growth phase. Induction of protein release over time is shown for three different growth phases. Culture densities and pH at harvest were as follows: mid-log, 5 × 107 spirochetes per ml, pH 7.61; late-log, 9 × 107 spirochetes per ml, pH 7.44; and stationary phase, 8 × 107 spirochetes per ml, pH 7.20. Spirochetes were resuspended to 1 × 109 to 2 × 109 spirochetes/ml in RPMI-1640 medium and radiolabeled with 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine for 60, 120, or 180 min. Panel A contains whole-cell lysates with 6.4 × 106 cpm per lane. Panel B contains conditioned medium equivalent to the whole-cell protein in the corresponding lanes in panel A. The arrows indicate protein bands shown by others to be induced in whole cells with progression to stationary phase. Molecular mass protein standards are indicated in kilodaltons. Panel C. Immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates (108 spirochetes) and conditioned medium (from 2 × 108 spirochetes) from the stationary-phase cells shown above were probed with specific antisera against flagellin, OspA, OspB, or Oms28.

Radioimmunoprecipitation of Oms28 secreted by strains B31, HB19, and N40.

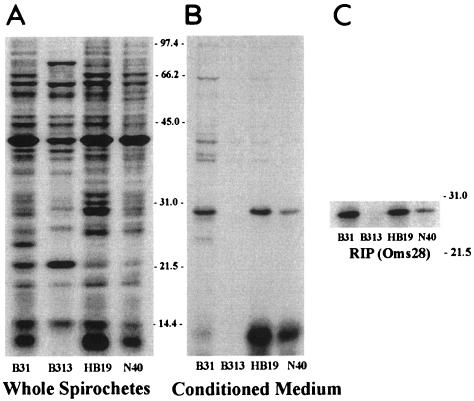

In the study first describing Oms28, Skare et al. demonstrated that a polyclonal antiserum produced against the porin from strain B31 recognizes membrane-associated Oms28 from other B. burgdorferi strains (54). To confirm that the extracellular secretion of Oms28 is not strain specific, we radiolabeled strains B31, HB19, B313, and N40 in RPMI medium as described above. Strains B31 and HB19 secreted large amounts of radiolabeled Oms28 into conditioned medium, whereas strain N40 released a smaller amount (Fig. 6B). The secreted form of Oms28 was recognized by RIP using polyclonal antiserum that was raised against a detergent-extracted Oms28 preparation (Fig. 6C). Strain B313 is reported to lack the 54-kb linear plasmid (lp54) that contains oms28 (48), and as expected, Oms28 was not observed by intrinsic labeling or RIP.

FIG. 6.

Radioimmunoprecipitation of Oms28 secreted by three B. burgdorferi strains. The autoradiogram in panel A contains [35S]methionine- and [35S]cysteine-labeled proteins of whole-cell lysates from 108 spirochetes. Each lane in Panel B contains the conditioned medium derived from the equivalent of 2 × 108 spirochetes. Panel C shows Oms28 recovery by RIP lanes from the conditioned medium equivalent of 5 × 108 spirochetes for three of the four strains examined.

DISCUSSION

The effective transfer and replication of B. burgdorferi between Ixodes species vectors and warm-blooded hosts demands an efficient and rapid adaptive response by the spirochete. Changes in transcriptional regulation (5, 32, 35, 43) and protein synthesis (1, 7, 42-45, 51) in response to factors such as temperature, pH, and host environment, both in vitro and in vivo, are well characterized. While these studies have described proteins localized to either the outer membrane or the protoplasmic cylinder, we demonstrate here that B. burgdorferi secretes proteins into the extracellular environment, including Oms28 and Bgp. The release of Oms28 and the profile of extracellular proteins are influenced by the growth phase of the spirochete.

The secretion of the Oms28 porin was monitored for up to 3 h by radiolabeling and immunoblot analysis. While Oms28 accumulated in the conditioned medium, pulse-chase experiments demonstrated that other radiolabeled proteins released immediately at the onset of the chase turned over with time. It is of interest to determine if this turnover is associated with proteolysis, and if so, whether proteolytic activity is spirochete or medium associated (55). Importantly, the pattern of secreted proteins in conditioned BSK II medium lacking serum and bovine serum albumin was identical to that obtained in RPMI medium. Spirochetes were also radiolabeled in serum-free BSK II medium containing a lipid supplement over a period of several days, but the albumin content of the conditioned medium prevented facile resolution of proteins by SDS-PAGE.

While the experiments reported here show extracellular protein secretion at spirochete densities of 4 × 108 spirochetes per ml and greater, secretion of Oms28 was also observed at spirochete densities of 107 per ml (data not shown). For mid- to late-logarithmic-phase cells, Oms28 is selectively released into the culture medium over time (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 5). However, when cells enter stationary phase (Fig. 5B, lanes 6 to 8), selective secretion of Oms28 decreases dramatically and a number of additional proteins appear in the medium, particularly between 21 and 33 kDa. In these whole cells, proteins of 42, 34, 29, 24 and 17 kDa in mass were induced as the spirochetes progressed to stationary phase. Some of these proteins correspond in size to proteins that are upregulated as spirochetes pass from logarithmic to stationary phase, including the band around 24 kDa that likely represents OspC, which has been detected in conditioned medium from mid-logarithmic-phase cells (data not shown).

Skare et al. established that Oms28 is a porin that contains a functional leader sequence, localizes to the B. burgdorferi outer membrane, and anomalously partitions with the aqueous phase following Triton X-114 extraction of whole spirochetes. While Oms28 was associated with OMV in these studies, the porin remained membrane associated even after incubation of OMV in salt-containing buffers (54). For the work described here, it was therefore important to determine whether the extracellular release of Oms28 occurs freely or whether it is OMV associated. Immunoblot analysis of the proteins recovered from conditioned medium (Fig. 3) suggests that the release of Oms28 under the experimental conditions employed in this study occurs by a vesicle-independent mechanism. The radiolabeling experiments support these findings, since conditioned medium derived from early- to mid-logarithmic-phase cells essentially lacks OspA and -B. OMV and membrane blebs are recoverable from culture medium at centrifugal forces of 25,000 × g and above (13). If the exoproteins described here were primarily associated with OMV or membrane blebs, then OspA and -B would have been more readily detected. However, OspA and -B lipoproteins were present in the conditioned medium of stationary-phase spirochetes along with flagellin, indicating that the physiological state of the spirochete influences exoprotein release. Also, serum starvation of B. burgdorferi induces changes in protein synthesis (1), so this nutritional stress could also be influencing the release of proteins from the spirochete.

The structure of native Oms28 has yet to be determined, but gram-negative bacterial porins are generally organized as trimers in their native form, with a secondary structure of amphipathic beta-pleated sheets spanning the outer membrane in a closed barrel conformation (11, 26). Oligomeric forms of Oms28 have been observed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels or associated with OMV preparations under native conditions (54). We also observed high-molecular-weight proteins in some of our radiolabeled preparations that may represent oligomeric forms of secreted Oms28 (data not shown). These studies need to be repeated under conditions that favor the resolution of oligomeric forms and then confirmed by immunoblotting. Importantly, the opportunity to obtain a detergent-free preparation of secreted Oms28 will simplify structural and biochemical characterization of the porin, and these preparations can be used directly in assays to test for pore-forming activity against cellular targets.

Two additional B. burgdorferi porins have been characterized; the P66 protein, also known as the Oms66 porin (53) and the P13 porin (39). The P13 porin is a surface-exposed integral outer membrane protein. Preliminary findings suggest that the P13 porin is not released into conditioned medium (data not shown).

The secretion of Bgp/Pfs-2 by B. burgdorferi is noteworthy, since this protein may be bifunctional; it serves as an adhesin by binding to glycosoaminoglycans and is predicted to exhibit a 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase activity. The enzymatic activity is also encoded by pfs-1, which is resident in an operon in B. burgdorferi containing metK and luxS (17, 24). Other bacteria that exhibit a quorum-sensing response have a similar operon, although the existence of a functional quorum-sensing response in B. burgdorferi is an ongoing point of debate. A third B. burgdorferi pfs paralogue, BBI06, located on lp28-4, has yet to be studied. BBI06 and Bgp/Pfs-2 have predicted signal sequences, while Pfs-1 does not, implying different cellular locations for these proteins. Since most bacteria encode only a single copy of pfs, this gene duplication in B. burgdorferi suggests an intriguing functional divergence for pfs, a notion that is supported by a likely bifunctional activity of Bgp/Pfs-2, the potential role of pfs-1 in quorum sensing, and the presence of a plasmid-encoded paralogue.

The GAG-binding activity of Bgp is well defined, a property shared with the decorin-binding proteins DbpA and -B (15, 19, 20). Bgp binds heparin and agglutinates erythrocytes, and recombinant protein blocks the attachment of spirochetes to target cells (28). Parveen et al. established that host-adapted spirochetes demonstrate enhanced binding to cultured endothelial cells and that DbpA and DbpB are expressed at higher levels on the spirochete surface (42). We have detected Bgp/Pfs-2 in several preparations of conditioned medium by sequencing but not by immunoblot analysis. Bgp/Pfs-2 is present in whole cells and conditioned medium in much smaller amounts than Oms28, which likely accounts for the difficulty in detecting Bgp/Pfs-2 with the antiserum currently available.

Whole-genome array studies reinforce the contention that secretion of Oms28 and Bgp/Pfs-2 may be significant in vivo. Two studies reveal that an increase in temperature leads to a threefold induction of oms28 expression. Of potential relevance, a number of hemolysins of the same paralogous family that are believed to comprise a holin-like system (12) were also induced by this temperature increase (37, 38). Bgp/Pfs-2 was also upregulated when the response to tick feeding was mimicked by altering the pH from 7.5 (at 23°C) to 6.8 (at 37°C) (44). In contrast, microarray analysis of host-adapted B. burgdorferi demonstrates that oms28 is strongly down-regulated in the host environment. However, in this same study (5), the P66 porin, (53), which is also an adhesin (9), was strongly induced.

Secretion of Bgp by B. burgdorferi could serve as a decoy to help the spirochete avert the immune response. Another intriguing model for the cooperative interaction of secreted forms of Bgp and Oms28 is suggested by the group A streptococci, which use an adhesin and the secreted pore-forming hemolysin, streptolysin O, to bind specifically to keratinocytes and stimulate a proinflammatory response (46).

More-thorough analysis of the borrelial secretome will likely reveal additional proteins of interest. The secretome of Helicobacter pylori contains 26 identified proteins, including a pore-forming vaculating toxin, serine protease, and three flagellar proteins (6). Similar pore-forming cytotoxins are produced by Staphylococcus species, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus species (4, 40), and it will be important to determine if Oms28 exhibits similar activity. A B. burgdorferi thiol-dependent hemolytic activity has been described (59), but efforts to identify the factor responsible have been elusive.

The secretion of the Oms28 porin and the GAG-binding Bgp adhesin by B. burgdorferi may be an important component of the host-pathogen interaction. Very recently, studies with mice show that isolates of B. burgdorferi that propagate to high levels in blood express significantly lower levels of Oms28 compared to isolates that are not disseminated (I. Schwartz, personal communication). Perhaps Oms28 is upregulated when the spirochete comes in contact with host cells or tissues, which may enhance navigation to new sites. Nutrient availability may also influence Oms28 homeostasis. In any event, the collective evidence suggests that the synthesis and outer membrane retention of at least one porin are regulated, in part, in response to host niche. Future experiments are planned to determine the oligomeric organization of secreted Oms28 and to assay these detergent-free preparations for hemolytic and cytotoxic activity.

In summary, we report the secretion of Oms28 and Bgp/Pfs-2 by B. burgdorferi into protein-free medium, the first description of extracellular protein secretion by the spirochete. A complete description of the B. burgdorferi secretome is in progress. The biochemical characterization of these exoproteins and characterization of the host response to these extracellular products will yield important new insights into the interaction of the spirochete with its hosts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH AREA grant AI29626-01 awarded to R.G.C. and institutional grants awarded to Middlebury College from The Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the American Association for the Advancement of Science/Merck Chemical Foundation, and the Vermont Genetics Network through NIH grant 1 P20 RR16462 from the BRIN program of the NCRR.

We thank Jonathan Skare, John Leong, and Ira Schwartz for valuable discussions and Grace Spatafora for helpful comments on the manuscript. The gifts of antisera from Jonathan Skare, Nikhat Parveen, Alan Barbour, Jonas Bunikis, Michael Kramer, Robert Gilmore, and Brian Stevenson were greatly appreciated.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

REFERENCES

- 1.Alban, P. S., P. W. Johnson, and D. R. Nelson. 2000. Serum-starvation-induced changes in protein synthesis and morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology 146:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour, A. G. 1984. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J. Biol. Med. 57:521-525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour, A. G., S. F. Hayes, R. A. Heiland, M. E. Schrumpf, and S. L. Tessier. 1986. A Borrelia-specific monoclonal antibody binds to a flagellar epitope. Infect. Immun. 52:549-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhakdi, S., H. Bayley, A. Valeva, I. Walev, B. Walker, U. Weller, M. Kehoe, and M. Palmer. 1996. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin, streptolysin-O, and Escherichia coli hemolysin: prototypes of pore-forming bacterial cytolysins. Arch. Microbiol. 165:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks, C. S., S. P. Hefty, S. E. Jolliff, and D. R. Akins. 2003. Global analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi genes regulated by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 71:3371-3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bumman, D., S. Aksu, M. Wendland, K. Janek, U. Zimny-Arndt, N. Sabarth, T. Meyer, and P. Jungblut. 2002. Proteome analysis of secreted proteins of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 70:3396-3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cluss, R. G., and J. T. Boothby. 1990. Thermoregulation of protein synthesis in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 58:1038-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cluss, R. G., A. S. Goel, H. Rehm, J. G. Schoenecker, and J. T. Boothby. 1996. Coordinate synthesis and turnover of heat shock proteins in Borrelia burgdorferi: degradation of DnaK during recovery from heat shock. Infect. Immun. 64:1736-1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coburn, J., W. Chege, L. Magoun, S. C. Bodary, and J. M. Leong. 1999. Characterization of a candidate Borrelia burgdorferi β3-chain integrin ligand identified using a phage display library. Mol. Microbiol. 34:926-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman, J. L., J. A. Gebbia, J. Piesman, J. L. Degen, T. H. Bugge, and J. L. Benach. 1997. Plasminogen is required for efficient dissemination of B. burgdorferi in ticks and for enhancement of spirochetemia in mice. Cell 89:1111-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowan, S. W., T. Schirmer, G. Rummel, M. Steiert, R. Ghosh, R. A. Pauptit, J. N. Jansonius, and J. P. Rosenbusch. 1992. Crystal structures explain functional properties of two E. coli porins. Nature 358:727-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damman, C. J., C. H. Eggers, D. S. Samuels, and D. B. Oliver. 2000. Characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi BlyA and BlyB proteins: a prophage-encoded holin-like system. J. Bacteriol. 182:6791-6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorward, D. W., T. G. Schwan, and C. F. Garon. 1991. Immune capture and detection of Borrelia burgdorferi antigens in urine, blood, or tissues from infected ticks, mice, dogs, and humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:1162-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenno, J. C., P. M. Hannam, W. K. Leung, M. Tamura, V. J. Uitto, and B. C. McBride. 1998. Cytopathic effects of the major surface protein and the chymotrypsinlike protease of Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 66:1869-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer, J. R., N. Parveen, L. Magoun, and J. M. Leong. 2003. Decorin-binding proteins A and B confer distinct mammalian cell type-specific attachment by Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7307-7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong, K. P., W. O. Chung, R. J. Lamont, and D. R. Demuth. 2001. Intra- and interspecies regulation of gene expression by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans LuxS. Infect. Immun. 69:7625-7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser, C. M., S. Casjens, W. M. Huang, G. G. Sutton, R. Clayton, R. Lathigra, O. White, K. A. Ketchum, R. Dodson, E. K. Hickey, M. Gwinn, B. Dougherty, J. F. Tomb, R. D. Fleischmann, D. Richardson, J. Peterson, A. R. Kerlavage, J. Quackenbush, S. Salzberg, M. Hanson, R. van Vugt, N. Palmer, M. D. Adams, J. Gocayne, and J. C. Venter. 1997. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390:580-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gebbia, J. A., J. L. Coleman, and J. L. Benach. 2001. Borrelia spirochetes upregulate release and activation of matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9) and collagenase 1 (MMP-1) in human cells. Infect. Immun. 69:456-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo, B. P., S. J. Norris, L. C. Rosenberg, and M. Höök. 1995. Adherence of Borrelia burgdorferi to the proteoglycan decorin. Infect. Immun. 63:3467-3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo, B. P., E. L. Brown, D. W. Dorward, L. C. Rosenberg, and M. Hook. 1998. Decorin-binding adhesions from Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 30:711-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Hellwage, J., T. Meri, T. Heikkilä, A. Alitalo, J. Panelius, P. Lahdenne, I. J. T. Seppälä, and S. Meri. 2001. The complement regulator Factor H binds to the surface protein OspE of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8427-8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodzic, E., S. Feng, K. J. Freet, and S. W. Barthold. 2003. Borrelia burgdorferi population dynamics and prototype gene expression during infection of immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice. Infect. Immun. 71:5042-5055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hübner, A., A. T. Revel, D. M. Nolen, K. E. Hagman, and M. V. Norgard. 2003. Expression of a luxS gene is not required for Borrelia burgdorferi infection of mice via needle inoculation. Infect. Immun. 71:2892-2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Indest, K. J., R. Ramamoorthy, M. Solé, R. D. Gilmore, B. J. B. Johnson, and M. T. Philipp. 1997. Cell-density-dependent expression of Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins in vitro. Infect. Immun. 65:1165-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koebnik, R., K. P. Locher, and P. Van Gelder. 2000. Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: barrels in a nutshell. Mol. Microbiol. 37:239-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraiczy, P., J. Hellwage, C. Skerka, H. Becker, M. Kirschfink, M. M. Simon, V. Brade, P. F. Zipfel, and R. Wallich. 2004. Complement resistance of Borrelia burgdorferi correlates with the expression of BbCRASP-1, a novel linear plasmid-encoded surface protein that interacts with human factor H and FHL-1 and is unrelated to Erp proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 279:2421-2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraiczy, P., C. Skerka, V. Brade, and P. F. Zipfel. 2001. Further characterization of complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 69:7800-7809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, S. H., S. Kim, S. C. Park, and M. J. Kim. 2002. Cytotoxic activities of Leptospira interrogans hemolysin SphH as a pore-forming protein on mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 70:315-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leong, J. M., H. Wang, L. Magoun, J. A. Field, P. E. Morrissey, D. Robbins, J. B. Tatro, J. Coburn, and N. Parveen. 1998. Different classes of proteoglycans contribute to the attachment of Borrelia burgdorferi to cultured endothelial and brain cells. Infect. Immun. 66:994-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margolis, N., D. Hogan, K. Tilly, and P. A. Rosa. 1994. Plasmid location of Borrelia purine biosynthesis gene homologues. J. Bacteriol. 176:6427-6432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mbow, M. L., R. D. Gilmore, Jr., and R. G. Titus. 1999. An OspC-specific monoclonal antibody passively protects mice from tick-transmitted infection by Borrelia burgdorferi B31. Infect. Immun. 67:5470-5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDowell, J. V., E. Tran, D. Hamilton, J. Wolfgang, K. Miller, and R. T. Marconi. 2003. Analysis of the ability of spirochete species associated with relapsing fever, avian borreliosis, and epizootic bovine abortion to bind factor H and cleave c3b. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3905-3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metts, S., J. V. McDowell, M. Theisen, P. R. Hansen, and R. T. Marconi. 2003. Analysis of the OspE determinants involved in the binding of factor H and OspE targeting antibodies elicited during infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 71:3587-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller, M. B., and B. L. Bassler. 2001. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:165-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narasimhan, S., F. Santiago, R. A. Koski, B. Brei, J. F. Anderson, D. Fish, and E. Fikrig. 2002. Examination of the Borrelia burgdorferi transcriptome in Ixodes scapularis during feeding. J. Bacteriol. 184:3122-3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ojaimi, C., C. Brooks, S. Casjens, P. Rosa, A. Elias, A. Barbour, A. Jasinskas, J. Benach, L. Katona, J. Radolf, M. Caimano, J. Skare, K. Swingle, D. Akins, and I. Schwartz. 2003. Profiling of temperature-induced changes in Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression by using whole genome arrays. Infect. Immun. 71:1689-1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Östberg, Y., M. Pinne, R. Benz, P. Rosa, and Sven Bergström. 2002. Elimination of channel-forming activity by insertional inactivation of the p13 gene in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 184:6811-6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papini, E., M. Zoratti, and T. L. Cover. 2001. In search of the Helicobacter pylori VacA mechanism of action. Toxicon 39:1757-1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parveen, N., and J. M. Leong. 2000. Identification of a candidate glycosaminoglycan-binding adhesin of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1220-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parveen, N., M. Caimano, J. D. Radolf, and J. M. Leong. 2003. Adaptation of the Lyme disease spirochaete to the mammalian host environment results in enhanced glycosaminoglycan and host cell binding. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1433-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramamoorthy, R., and D. Scholl-Meeker. 2001. Borrelia burgdorferi proteins whose expression is similarly affected by culture temperature and pH. Infect. Immun. 69:2739-2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramamoorthy, R., and M. T. Philipp. 1998. Differential expression of Borrelia burgdorferi proteins during growth in vitro. Infect. Immun. 66:5119-5124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Revel, A. T., A. M. Talaat, and M. V. Norgard. 2002. DNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1562-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz, N., B. Wang, A. Pentland, and C. M. Caparon. 1998. Streptolysin O and adherence synergistically modulate proinflammatory responses of keratinocytes to group A streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 27:337-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryan, J. R., J. F. Levine, C. S. Apperson, L. Lubke, R. A. Wirtz, P. A. Spears, and P. E. Orndorff. 1998. An experimental chain of infection reveals that distinct Borrelia burgdorferi populations are selected in arthropod and mammalian hosts. Mol. Microbiol. 30:365-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sadziene, A., D. D. Thomas, and A. G. Barbour. 1995. Borrelia burgdorferi mutant lacking Osp: biological and immunological characterization. Infect. Immun. 63:1573-1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salgers, A. A., and D. D. Whitt. 2002. Biochemical pathogenesis: a molecular approach, 2nd ed., p. 187-197. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 50.Schauder, S., K. Shokat, M. G. Surette, and B. L. Bassler. 2001. The LuxS family of bacterial autoinducers: biosynthesis of a novel quorum-sensing signal molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 41:463-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwan, T. G., J. Piesman, W. T. Golde, M. C. Dolan, and P. A. Rosa. 1995. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2909-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skare, J. T., E. S. Shang, D. M. Foley, D. R. Blanco, C. I. Champion, T. Mirzabekov, Y. Sokolov, B. L. Kagan, J. N. Miller, and M. A. Lovett. 1995. Virulent strain associated outer membrane proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Clin. Investig. 96:2380-2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skare, J. T., T. A. Mirzabekov, E. S. Shang, D. R. Blanco, H. Erdjument-Bromage, J. Bunikis, S. Bergstrom, P. Tempst, B. L. Kagan, J. N. Miller, and M. A. Lovett. 1997. The Oms66 (p66) protein is a Borrelia burgdorferi porin. Infect. Immun. 65:3654-3661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skare, J. T., C. I. Champion, T. A. Mirzabekov, E. S. Shang, D. R. Blanco, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, B. L. Kagan, J. N. Miller, and M. A. Lovett. 1996. Porin activity of the native and recombinant outer membrane protein Oms28 of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 178:4909-4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sohaskey, C. D., and A. G. Barbour. 1999. Esterases in serum-containing growth media counteract chloramphenicol acetyltransferase activity in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:655-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steere, A. C. 2001. Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevenson, B., and K. Babb. 2002. LuxS-mediated quorum sensing in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Infect. Immun. 70:4099-4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitmore, W. M., and C. F. Garon. 1993. Specific and nonspecific responses of murine B cells to membrane blebs of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 61:1460-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams, L. R., and F. E. Austin. 1992. Hemolytic activity of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 60:3224-3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]