Short abstract

Patients would be safer if drug companies disclosed adverse events before licensing

The history of the development and marketing of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is both fascinating and frightening. It offers a strange combination of stunning commercial successes and dramatic calamities, the latest concerning the recently withdrawn drug rofecoxib (Vioxx).1

In the 1960s research showed that salicylates were good for pain relief in rheumatoid arthritis, but as with steroids, their use was limited by toxicity.2 So the major pharmaceutical companies developed non-salicylate, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Over the subsequent 40 years we have seen a procession of new agents come and go, each one being heralded as either more efficacious or less toxic than its competitors. As new NSAIDs appeared, the indications steadily broadened from inflammatory diseases to almost any painful condition. Each time a new drug was launched the market expanded, resulting in annual estimated sales of more than $20bn (£11.1bn; €16.1bn) worldwide.2

The first big problem with a new NSAID occurred in the 1980s with benoxaprofen (Opren).3 This drug, developed by Eli Lilly, was marketed on the basis of a unique mode of action. But it soon became clear that its use was associated also with novel adverse events, including photosensitivity and hepatotoxicity. The company went on actively marketing the drug until forced to withdraw it when several older people had died of liver failure after using benoxaprofen.4

Now we confront a similar, but arguably more serious, problem with new NSAIDs. In the early 1990s two isoforms of cyclo-oxygenase were discovered, with distinct patterns of expression, COX-1 and COX-2.2 The anti-inflammatory properties of NSAIDs were said to be related to inhibition of COX-2, whereas gastrointestinal adverse effects occurred because of a COX-1 inhibition5—giving remarkable emphasis to the gastrointestinal toxicity of NSAIDs, while largely ignoring other adverse events.6

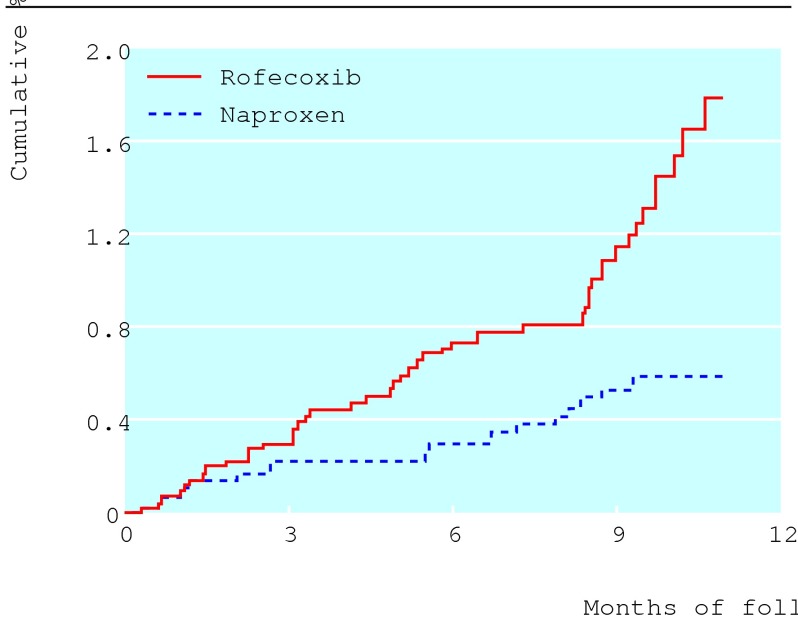

One of the first NSAIDs to be heavily marketed as a COX-2 selective inhibitor, capable of efficacy without serious toxicity, was celecoxib (Celebrex). Pfizer still promotes this agent on the basis of the CLASS study,7 despite the fact that this pivotal trial has been discredited,8 and that doubts have been cast on the selectivity of celecoxib.2 A subsequent agent was rofecoxib (Vioxx) produced by Merck Sharp & Dohme. While the corresponding landmark trial, VIGOR,9 provided robust evidence for rofecoxib's gastrointestinal safety, it raised concerns about its cardiovascular toxicity (figure), including a particularly worrying increase in the risk of myocardial infarction (relative risk 5.00, 95% confidence interval 1.72 to 14.29).2,10

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for serious thrombotic cardiovascular adverse events observed in the VIGOR trial (reference 9), which was published in 2000 (relative risk for rofecoxib versus naproxen 2.37, 95% confidence interval 1.39 to 4.06; reference 2). Adapted from Li Q. Statistical reviewer briefing document for the advisory committee, 2001. www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3677b2_04_stats.pdf (accessed 30 Sep 2004)

On the basis of purely theoretical reasoning—and in the absence of any evidence from randomised controlled trialsw1—Merck proposed that the explanation for the observed difference in rates of myocardial infarction was the cardioprotective potential of the comparator drug used in VIGOR, naproxen.w2 A press release on 22 May 2001 was entitled “Merck reconfirms favorable cardiovascular safety of Vioxx.” Numerous publications by Merck's consultants and employees supported this notion.w2 Now, nearly four years after publication of VIGOR, Merck has withdrawn rofecoxib because of its cardiovascular toxicity, quoting the results of an as yet unpublished, placebo controlled, long term trial as their reason for taking this action.1

We have three concerns. Firstly, the “Vioxx story” indicates that we urgently need to determine whether the cardiovascular effects of rofecoxib are a class effect applicable to all COX-2 selective inhibitors—and if so, how selective the COX-2 inhibition needs to be to have this adverse effect. Secondly, we believe that the current widespread use of NSAIDs for non-inflammatory pain has to be reconsidered. Thirdly, we must find ways of preventing further similar episodes (box).

Suggested measures to ensure drug safety before definite licensing of a drug

Legal requirement for drug companies to register all randomised controlled trials prospectively

Legal requirement for drug companies to make all data on serious adverse events from clinical studies publicly available immediately after study completion

Continuously updated systematic reviews of adverse events based on published and unpublished data from randomised controlled trials and observational studies

Phased introduction of new interventions in independent, large scale, randomised trials before definite drug licensing

Clear cut financial firewalls between pharmaceutical companies and researchers performing systematic reviews and clinical studies

Single phase III drug trials are simply not big enough to detect relatively uncommon but important adverse events, which may affect large numbers of people in routine clinical use.6 The potential public health impact of previously undetected drug related adverse events is likely to be made worse if widely marketed new drugs are prescribed haphazardly and rapidly to large numbers of people. Within five months of the launch of rofecoxib, more than 42 000 patients had been prescribed the drug in England,11 even though newly marketed drugs carry a black triangle warning, indicating an incomplete safety profile. Unfortunately, postmarketing surveillance is not a panacea to determine safety, as methodological flaws may produce inaccurate results.

We therefore recommend that drug companies are legally required to make all data on serious adverse events from clinical studies available to the public immediately after completion of the research. This will allow independent, timely, and updated systematic reviews of serious adverse events. In addition, we advocate the phased introduction of new interventions through randomised trials, which are independent from the pharmaceutical industry and are large enough to study rare outcomes, together with systematic, more robust, and comprehensive approaches to pharmacovigilance.12 Although these measures will not be popular with pharmaceutical companies, they will limit the numbers of patients exposed unsystematically to unknown hazards and provide robust and unbiased evidence on adverse events before a drug is licensed fully.

Supplementary Material

Additional reference w1 and w2 are on bmj.com

Additional reference w1 and w2 are on bmj.com

Competing interests: SE is coordinating editor of the Cochrane Heart Group, which produces systematic reviews not funded by the pharmaceutical industry of the effects of interventions for heart diseases. RMM worked at the Drug Safety Research Unit between 1997 and 1999, during which time the unit received unconditional donations from pharmaceutical companies.

References

- 1.Merck announces voluntary worldwide withdrawal of VIOXX®. News release. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck, 2004. www.vioxx.com/vioxx/documents/english/vioxx_press_release.pdf (accessed 30 Sep 2004).

- 2.Jüni P, Dieppe P. Older people should NOT be prescribed “coxibs” in place of conventional NSAIDs. Age Ageing 2004;33: 100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith R. Medical journals and pharmaceutical companies: uneasy bedfellows. BMJ 2003;326: 1202-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taggart HM, Alderdice JM. Fatal cholestatic jaundice in elderly patients taking benoxaprofen. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284: 1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kargman S, Charleson S, Cartwright M, Frank J, Riendeau D, Mancini J, et al. Characterization of Prostaglandin G/H Synthase 1 and 2 in rat, dog, monkey, and human gastrointestinal tracts. Gastroenterology 1996;111: 445-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dieppe P, Bartlett C, Davey P, Doyal L, Ebrahim S. Balancing benefits and harms: the example of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. BMJ 2004;329: 31-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, Simon LS, Pincus T, Whelton A, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. The CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000;284: 1247-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jüni P, Rutjes AW, Dieppe PA. Are selective COX 2 inhibitors superior to traditional non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs? BMJ 2002;324: 1287-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Burgos-Vargas R, Davis B, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000;343: 1520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topol EJ. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective COX-2 inhibitors. JAMA 2001;286: 954-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Layton D, Riley J, Wilton LV, Shakir SA. Safety profile of rofecoxib as used in general practice in England: results of a prescription-event monitoring study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2003;55: 166-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waller PC, Evans SJ. A model for the future conduct of pharmacovigilance. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2003;12: 17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.