Abstract

Objective To examine the temporal relation between depression and cognitive impairment in old age.

Design Prospective, population based study with four years of follow up.

Setting City of Leiden, the Netherlands.

Participants 500 people aged 85 years at recruitment.

Main outcome measures Annual assessments of depressive symptoms (15 item geriatric depression scale), global cognitive function (mini-mental state examination), attention (Stroop test), processing speed (letter digit coding test), and immediate and delayed recall (12 word learning test).

Results At 85 years old, participants' depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment were highly significantly correlated (P < 0.001). During follow up, an accelerated annual increase of depressive symptoms was associated with impaired attention (0.08 points (95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.16)), immediate recall (0.17 points (0.09 to 0.25)), and delayed recall (0.10 points (0.02 to 0.18)) at baseline. In contrast, depressive symptoms at baseline were not related to an accelerated cognitive decline during follow up (P > 0.05).

Conclusion Caregivers should be aware of the development of depressive symptoms when cognitive impairment is present. However, the presence of depression only does not increase the risk of cognitive decline.

Introduction

Depression and cognitive impairment are among the most important mental health problems in elderly people. Both conditions have severe consequences, including diminished quality of life, functional decline, increased use of services, and high mortality.1 Late onset depression and cognitive impairment often occur together, suggesting a close association between them.2-4 It is not known, however, whether depression leads to cognitive decline or vice versa.4,5

Clinical practice and research evidence suggest that depression precedes cognitive decline in old age.5-10 However, inferring a relationship is hampered because most studies on this topic examined only the association between depression and the subsequent development of cognitive impairment.6-14 As depression may be an early sign rather than an independent risk factor for cognitive impairment, the temporal relation between depression and cognitive impairment in old age remains unclear.

Hitherto, only one study has investigated the temporal relation between depression and cognitive impairment in people aged 65 years and older.15 The study is limited, however, by its use of the clinical diagnosis of depression and dementia as a dichotomous endpoint. We therefore followed up 500 elderly people living in the community with annual assessments of depressive symptoms and cognitive function in order to determine their temporal relation.

Participants and methods

Participants

The Leiden 85-plus study is a prospective, population based study of all 85 year old inhabitants of Leiden. Between 1 September 1997 and 1 September 1999, 599 participants were enrolled (response rate 87%). They were visited annually from the age of 85 to 89 years at their home for face to face interviews, and all gave their informed consent to participate.16 For the present analysis, we included the 500 participants (83%) without severe cognitive impairment at baseline (mini-mental state examination score ≥ 19 points).

Cognitive function

We assessed

Global cognitive function with the mini-mental state examination17—scores range from 0 to 30 points, with lower scores indicating impaired cognitive functioning

Attention with the third chart of the 40 item Stroop test—time needed to name the ink colour of incongruously printed names of colours, with higher scores indicating poorer attention

Processing speed with the letter digit coding test—total number of correct digits assigned to letters according to a code key in 60 seconds, with lower scores indicating a slower speed

Immediate and delayed recall with the 12 word learning test—12 pictures are presented to the participant, who is then asked to recall them. This procedure is done three times. Outcome for immediate recall is the total number of words correctly recalled immediately after each procedure; outcome for delayed recall is the number correctly recalled after 20 minutes. Lower scores indicate impaired memory.

Parallel versions for the coding and memory tests, identical procedures but with different items, were available to prevent learning effects. These neuropsychological tests are sensitive to small differences in elderly people.18 We did not assess attention, processing speed, or immediate and delayed recall in participants with a mini-mental state exam score of ≤ 18 points because these tests lack reliability and validity in people with severe cognitive impairment.

Depressive symptoms

We assessed depressive symptoms with the 15 item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15), a questionnaire specifically developed for screening for depressive symptoms in elderly populations.19 Its use has been validated in the Leiden 85-plus study,20 and we have shown previously that it can detect longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms.21 We did not use it with participants with a mini-mental state exam score of ≤ 18 points because it lacks reliability and validity in people with severe cognitive impairment.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the cross sectional correlation between depressive symptoms and cognitive function with Pearson's correlation coefficient. To assess the temporal relation between depression and cognitive function, we used separate linear mixed models adjusted for sex and level of education. Mixed models use all available data during follow up, can properly account for correlation between repeated measurements, and can handle missing data more appropriately than traditional models. They allow for the use of time independent and time dependent covariates.22

Impact of cognitive function on depression

We examined the impact of cognitive function at baseline on the course of depressive symptoms, restricting the analysis to participants without significant depressive symptoms at baseline (geriatric depression scale score ≤ 2 points). Our models included cognitive function at baseline, time, and the interaction of cognitive function at baseline and time. The estimate for “cognitive function at baseline” reflects the cross sectional impact of cognitive function on depressive symptoms averaged across all time points. The estimate for “time” reflects the annual change in depressive symptoms. The estimate for “interaction” of cognitive function at baseline and time reflects the additional annual effect per standard deviation of the mean of cognitive function at baseline on the course of depressive symptoms. The impact of cognitive function at baseline on the course of depressive symptoms is reflected by the estimate for “interaction” of cognitive function and time.

Impact of depression on cognitive function

We examined the impact of depressive symptoms at baseline on the course of cognitive function, restricting the analysis to participants without serious cognitive impairment at baseline (mini-mental state exam score ≥ 24 points). Models included depressive symptoms at baseline, time, and the interaction of depressive symptoms at baseline and time. The estimate for “depressive symptoms at baseline” reflects the cross sectional impact of depressive symptoms on cognitive function averaged across all time points. The estimate for “time” reflects the annual change of cognitive function. The estimate for “interaction” of depressive symptoms at baseline and time reflects the additional annual effect per standard deviation of the mean of depressive symptoms at baseline on the course of cognitive function. The impact of depressive symptoms at baseline on the course of cognitive function is reflected by the estimate for “interaction” of depressive symptoms and time.

Results

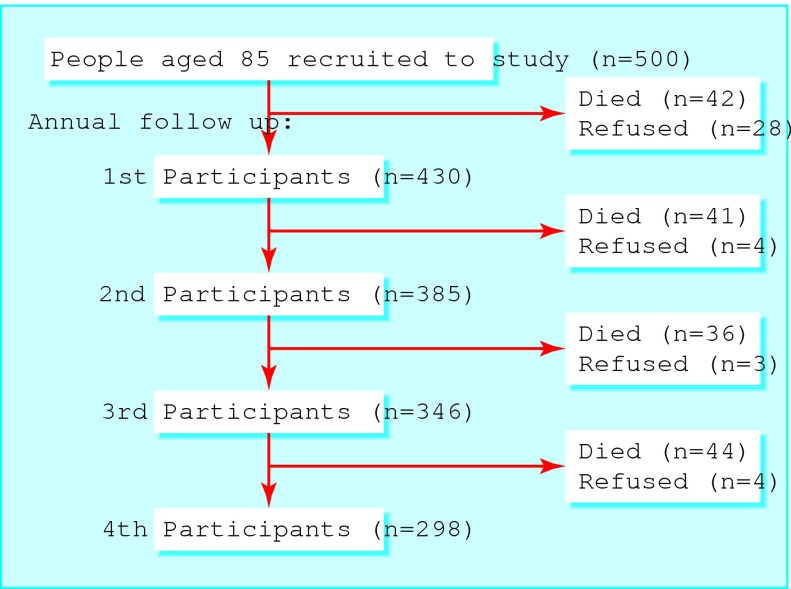

The figure shows the annual follow up visits for the 500 participants included in our study. During 1459 person-years of follow up (mean per person, 2.9 years), 39 people (8%) refused to participate in the repeated annual measurements, most of them at the first follow up visit. Of the 334 participants without significant depressive symptoms at baseline (geriatric depression scale score ≤ 2 points), 97 (29%) died and 28 (8%) declined to participate during follow up. Of the 415 non-demented participants at baseline (mini-mental state examination score ≥ 24 points), 124 (30%) died and 32 (8%) declined to participate during follow up.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through study

Table 1 shows the 500 participants' demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline. Of these participants, 184 (37%) were men, 303 (61%) had only a low level of education (≤ 6 years of schooling), 334 (67%) had no significant depressive symptoms (geriatric depression scale score ≤ 2 points), and 415 (83%) had no serious cognitive impairment (mini-mental state exam score ≥ 24 points).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 500 people aged 85 years living in the community. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Men |

184 (37) |

| Low level of education |

303 (61) |

| Living independently |

444 (89) |

| Depressive symptoms (15 item geriatric depression scale): |

|

| Median score (interquartile range) |

2 (1-3) |

| Score ≤2 points |

334 (67) |

| Cognitive function: |

|

| Mini-mental state examination: |

|

| Median score (interquartile range) |

27 (24-28) |

| Score ≥24 points |

415 (83) |

| Median (interquartile range) Stroop test score |

74 (60-97) |

| Median (interquartile range) letter digit coding test score |

16 (12-21) |

| Median (interquartile range) word learning test score, immediate recall |

25 (21-28) |

| Median (interquartile range) word learning test score, delayed recall | 9 (7-11) |

Table 2 shows the cross sectional correlation between depressive symptoms and cognitive function at baseline. Depressive symptoms were significantly correlated with lower scores for global cognitive function, attention, processing speed, and immediate and delayed recall and with higher test scores for attention (indicating reduced attention) (all P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Cross sectional correlation of depressive symptoms* with various measures of cognitive function in 500 people aged 85 years living in the community

| Cognitive function test | Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Global cognitive function |

−0.296 |

<0.001 |

| Attention |

0.182 |

<0.001 |

| Processing speed |

−0.238 |

<0.001 |

| Immediate recall |

−0.194 |

<0.001 |

| Delayed recall | −0.182 | <0.001 |

Depressive symptoms assessed with the 15 item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15).

Table 3 shows the impact of cognitive function at baseline on the course of depressive symptoms in the 334 non-depressed participants at baseline (geriatric depression scale score ≤ 2 points). An accelerated annual increase of depressive symptoms during follow up was associated with impaired attention (0.08 points (95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.16)), poorer immediate recall (0.17 points (0.09 to 0.25)), and poorer delayed recall (0.10 points (0.02 to 0.18)) at baseline. These estimates remained similar when we included participants with a geriatric depression scale score of ≥ 2 points (data not shown).

Table 3.

Impact of cognitive function at baseline on depressive symptoms from age 85 to 89 years in 334 people living in the community without depressive symptoms at baseline (GDS-15 score ≤2 points). Impact is additional annual increase of depressive symptoms score per SD of cognitive function test score at baseline (2.65 for global cognitive function, 31.59 for attention, 7.08 for processing, 5.72 for immediate recall, and 2.74 for delayed recall)

| Cognitive function test | Additional annual increase of GDS-15 score (SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Global cognitive function |

−0.06 (0.04) |

0.17 |

| Attention |

0.08 (0.04) |

0.05 |

| Processing speed |

−0.03 (0.04) |

0.42 |

| Immediate recall |

−0.17 (0.04) |

0.01 |

| Delayed recall | −0.10 (0.04) | 0.02 |

Associations were assessed by separate linear mixed models adjusted for sex and educational level. GDS-15 score increased highly significantly over time in all models (P<0.001). GDS-15=15 item geriatric depression scale.

Table 4 shows the impact of depressive symptoms at baseline on the course of cognitive function in the 415 non-demented participants at baseline (mini-mental state exam ≥ 24 points). Depressive symptoms at baseline were not associated with an accelerated cognitive decline during follow up (P > 0.05). These estimates remained similar when we included participants with a mini-mental state exam score ≤ 24 points (data not shown).

Table 4.

Impact of depressive symptoms at baseline (GDS-15 score) on cognitive decline from age 85 to 89 years in 415 people living in the community without cognitive impairment at baseline (MMSE score ≥24 points). Impact is additional annual impact on cognitive function per SD of mean GDS-15 score at baseline (2.11)

| Cognitive function test | Additional annual impact on cognitive function score (SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Global cognitive function |

−0.01 (0.04) |

0.79 |

| Attention |

−0.49 (0.38) |

0.20 |

| Processing speed |

−0.09 (0.06) |

0.14 |

| Immediate recall |

−0.08 (0.07) |

0.21 |

| Delayed recall | 0.001 (0.03) | 0.97 |

Associations were assessed by separate linear mixed models adjusted for sex and educational level. All measures of cognitive function showed highly significant decline over time (P<0.001).

GDS-15=15 item geriatric depression scale.

MMSE=mini-mental state examination.

Discussion

Depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment were highly significantly correlated cross sectionally, showing that they do co-occur in old age. Crucially, we found that cognitive impairment at baseline was associated with an accelerated increase of depressive symptoms, whereas depressive symptoms at baseline were not related to an accelerated cognitive decline. Thus our data show that cognitive impairment preceded the onset of depressive symptoms but not vice versa.

How does cognitive impairment lead to depression in old age?

We found specifically that impairment of attention and memory preceded the development of depressive symptoms. The awareness of cognitive decline may cause depression as a psychological reaction to the loss of cognitive functioning. Indeed, memory complaints in old age may be an early sign of dementia and, as such, upset elderly people.23 Thus, adequate functioning of attention and memory may be especially important to elderly people, explaining why their loss is associated with an accelerated increase of depressive symptoms. A common aetiology or sharing of risk factors is less likely to explain the association between depression and cognitive impairment. In that case, we would have expected that depressive symptoms precede cognitive decline also.

Comparison with other studies

Inferring causality in the relation between depression and cognitive impairment in old age has been hampered by the fact that most studies have examined only one direction of this relation. Some studies found that depression is a risk factor for the development of cognitive decline,6-10 whereas others could not confirm this finding.11-14 Examination of both directions of the relation between depression and cognitive impairment shows that depression in old age is a concomitant phenomenon of already existing cognitive impairment rather than an independent risk factor. Our findings, based on various measures of cognitive function instead of a dichotomous end point, are in line with those from a large population based study in people aged 65 and older showing that depression is an early manifestation rather than a predictor of Alzheimer's disease.15 Thus, in elderly people the presence of depressive symptoms does not mean that they are at increased risk of cognitive decline.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

The major strengths of this study are the annual assessments of depressive symptoms and various cognitive functions, the use of linear mixed models, and the population based sample of elderly people. A possible weakness is that depression was not formally diagnosed. However, depressive symptoms in old age have similarly serious consequences as do depressive disorders.24 Hence, depression may better be interpreted as a continuum of depressive symptoms rather than the mere presence or absence of a depressive disorder.

Conclusions

We found that cognitive decline preceded depression in old age—specifically impairment of attention or memory preceded the development of depressive symptoms. Depression seems to be a concomitant symptom of cognitive impairment rather than an independent risk factor. Therefore, caregivers should pay special attention to early detection and treatment of depressive symptoms in elderly people with cognitive impairment.

What is already known on this topic?

Depression and cognitive impairment often occur together in old age

The temporal relation between depression and cognitive impairment is unclear

What this study adds?

Impairment of attention or memory in old age precedes the development of depressive symptoms

Presence of depressive symptoms, however, is not related to accelerated cognitive decline

Contributors: All authors participated in the planning, conduct, and reporting of the study. JG, MLS, RGJW, and RCvdM supervised and commented on all drafts. All authors approved the final manuscript. DJV is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by unrestricted grants from the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research (ZonMw) and the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sports.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The medical ethics committee of Leiden University Medical Centre approved the study.

References

- 1.Macdonald AJD. Mental health in old age. BMJ 1997;315: 413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Migliorelli R, Teson A, Sabe L, Petracchi M, Leiguarda R, Starkstein SE. Prevalence and correlates of dysthymia and major depression among patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152: 37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zubenko GS, Zubenko WN, McPherson S, Spoor E, Marin DB, Farlow MR, et al. A collaborative study of the emergence and clinical features of the major depressive syndrome of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160: 857-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jorm AF. History of depression as a risk factor for dementia: an updated review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001;35: 776-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schweitzer I, Tuckwell V, O'Brien J, Ames D. Is late onset depression a prodrome to dementia? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;17: 997-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devanand DP, Sano M, Tang M-X, Taylor S, Gurland BJ, Wilder D, et al. Depressed mood and the incidence of Alzheimer's disease in the elderly living in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53: 175-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaffe K, Blackwell T, Gore R, Sands L, Reus V, Browner WS. Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in nondemented elderly women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56: 425-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paterniti S, Verider-Taillerfer M-H, Dufouil C, Alpérovitch A. Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in elderly people. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181: 406-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green RC, Cupples LA, Kurz A, Auerbach S, Go R, Sadovnick D, et al. Depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2003;60: 753-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Bennett DA, Bienias JL, Evans DA. Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in a community population of older persons. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75: 126-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dufouil C, Fuhrer R, Dartigues J-F, Alpérovitch A. Longitudinal analysis of the association between depressive symptomatology and cognitive deterioration. Am J Epidemiol 1996;144: 634-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson AS, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Jorm AF, Rodgers B, Jacomb P, et al. The course of depression in the elderly: a longitudinal community-based study in Australia. Psychol Med 1997;27: 119-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cervilla JA, Prince M, Joels S, Mann A. Does depression predict cognitive outcome 9 to 12 years later? Evidence from a prospective study of elderly hypertensives. Psychol Med 2000;30: 1017-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broday H, Luscombe G, Anstey KJ, Cramsie J, Andrews G, Peisah C. Neuropsychological performance and dementia in depressed patients after 25-year follow-up: a controlled study. Psychol Med 2003;33: 1263-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen P, Ganguli M, Mulsant BH, DeKosky ST. The temporal relationship between depressive symptoms and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56: 261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bootsma-van der Wiel A, van Exel E, de Craen AJM, Gusskloo J, Lagaay AM, Knook DL, et al. A high response is not essential to prevent selection bias: results from the Leiden 85-plus study. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55: 1119-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12: 189-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houx PJ, Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Ford I, Bollen EL, et al. Testing cognitive function in elderly populations: the PROSPER study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73: 385-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982;1: 37-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Craen AJM, Heeren TJ, Gussekloo J. Accuracy of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) in a community sample of the oldest old. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18: 63-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinkers DJ, Gussekloo J, Stek ML, Westendorp RGJ, van der Mast RC. The 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) detects changes in depressive symptoms after a major negative life event. The Leiden 85-plus study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19: 80-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61: 310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15: 983-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geerlings SW, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Smit JH, Schoevers RS, de Beurs E, et al. Duration and severity of depression predict mortality in older adults in the community. Psychol Med 2002;32: 609-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]