Abstract

Objectives To review current practice in the analysis and reporting of epidemiological research and to identify limitations.

Design Examination of articles published in January 2001 that investigated associations between risk factors/exposure variables and disease events/measures in individuals.

Setting Eligible English language journals including all major epidemiological journals, all major general medical journals, and the two leading journals in cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Main outcome measure Each article was evaluated with a standard proforma.

Results We found 73 articles in observational epidemiology; most were either cohort or case-control studies. Most studies looked at cancer and cardiovascular disease, even after we excluded specialty journals. Quantitative exposure variables predominated, which were mostly analysed as ordered categories but with little consistency or explanation regarding choice of categories. Sample selection, participant refusal, and data quality received insufficient attention in many articles. Statistical analyses commonly used odds ratios (38 articles) and hazard/rate ratios (23), with some inconsistent use of terminology. Confidence intervals were reported in most studies (68), though use of P values was less common (38). Few articles explained their choice of confounding variables; many performed subgroup analyses claiming an effect modifier, though interaction tests were rare. Several investigated multiple associations between exposure and outcome, increasing the likelihood of false positive claims. There was evidence of publication bias.

Conclusions This survey raises concerns regarding inadequacies in the analysis and reporting of epidemiological publications in mainstream journals.

Introduction

Observational epidemiology generates a plethora of publications across numerous epidemiological and medical journals. Many texts tackle the quality of epidemiological studies,1-8 but few directly focus on epidemiological publications.9-14 We reviewed the quality and methodological acceptability of research epidemiology published in January 2001. We concentrated on analytical epidemiology—that is, studies that used observational data on people from the general population to quantify relations between exposures and disease.

Methods

We selected three types of English language journals: public, environmental, and occupational health journals15 with impact factor > 2, plus the International Journal of Epidemiology and the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health to enhance international representation; general and internal medicine journals with impact factor > 2 and Circulation and the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, being the highest impact journals in cardiovascular disease and cancer. We then identified eligible articles published in January 2001. Eligible epidemiological articles analysed observational data in individuals to quantify associations between risk factors and disease outcomes. We excluded randomised controlled trials; observational studies of treatments; studies of people with disease, which do not relate to general population risk; and ecological studies, time trends, etc, that did not investigate individual associations.

For each article two authors independently completed a standard proforma, each author evaluating 25% of articles. Items were extracted using precoded boxes and open text fields (box). Minor inconsistencies were resolved by consensus, while a few disagreements were resolved via a third party.

Results

Journals and participants

We identified 73 eligible epidemiological articles in 20 journals: 54 were in epidemiology journals (table 1). North American and European populations were studied in 39 and 28 articles, respectively. Only six articles studied populations in developing countries. Authors and participants tended to be from the same country, with eight exceptions.

Table 1.

The 73 epidemiological publications in January 2001 by journal and country of participants

| No of articles | |

|---|---|

| Epidemiological journals: |

|

|

Am J Epidemiol |

13 |

|

Epidemiology |

9 |

|

Ann Epidemiol |

6 |

|

Int J Epidemiol* |

6 |

|

Am J Public Health |

5 |

|

Occupat Environ Med |

5 |

|

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev |

4 |

|

Cancer Causes Control |

3 |

|

J Epidemiol Cancer Health |

2 |

|

J Clin Epidemiol |

1 |

| General medical journals: |

|

|

Am J Med |

2 |

|

Ann Intern Med |

2 |

|

BMJ |

2 |

|

JAMA |

2 |

|

Lancet |

2 |

|

Arch Intern Med |

1 |

|

J Gen Intern Med |

1 |

|

N Engl J Med |

1 |

| Specialist medical journals: |

|

|

Circulation |

4 |

|

J Natl Cancer Inst |

2 |

| Country of study subjects† |

|

| United States |

37 |

| Canada |

3 |

| United Kingdom |

9 |

| Rest of Europe |

20 |

| South and Central America |

1 |

| Africa |

2 |

| Asia | 6 |

This journal is bimonthly, so we chose a random half of articles published in February 2001.

Three studies had participants from more than one continent.

Study designs and outcomes

There were 37 cohort studies, 25 case-control studies, 10 cross sectional studies, and one case-cohort study (table 2). Twenty eight articles, mostly case-control studies, investigated cancers, and 16, mostly cohort studies, investigated cardiovascular disease. Even after we excluded the specialist cancer and cardiology journals, only 31% of articles studied other diseases. Most disease outcomes were binary: non-fatal events or deaths, or both. Seven articles investigated quantitative disease markers, and four studied multiple category outcomes (for example, disease severity).

Table 2.

Principal study outcomes by type of design in 73 epidemiological publications

| Principal outcome | Cohort | Case-control | Cross sectional | Case-cohort | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer |

10 |

17 |

— |

1 |

28 |

| Cardiovascular disease |

12 |

2 |

2 |

— |

16 |

| All cause mortality |

8 |

— |

— |

— |

8 |

| Gynaecological |

1 |

4 |

— |

— |

5 |

| Mental health |

2 |

— |

2 |

— |

4 |

| Neurological |

1 |

1 |

— |

— |

2 |

| Liver function |

1 |

— |

1 |

— |

2 |

| Lung function |

1 |

— |

1 |

— |

2 |

| Other |

1 |

1 |

4 |

— |

6 |

| Total | 37 | 25 | 10 | 1 | 73 |

Cohort studies varied in size from 317 to 1.5 million participants (median 5072), the largest studies using official databases. Most exceeded 10 years' follow up, though in two studies it was one year. Eight cohort studies gave no information on drop outs. Twenty four cohort study articles gave no information on refusals to participate, perhaps relying on earlier publications. Follow up entailed monitoring for disease outcomes (30 studies), planned visits (13 studies), and questionnaires (five studies). The number of principal outcome events ranged from 44 to 28 795 (median 414). Five studies had fewer than 100 events.

Case-control studies mostly used some matching of controls to cases (21 of 25 studies). Five were nested within a cohort study. Fifteen studies had more than one control per case. Cases were mostly from hospitals or clinics (11 studies) or population surveillance (eight studies). Controls were commonly from the general population (13 studies) or hospitals or clinics (seven studies). The number of cases varied from under 100 to over 8000 (median 347).

Cross sectional studies—Half of these selected random samples from the general population. Study size varied from under 100 to over 10 000 participants (median 1500).

The case-cohort study investigated alcohol consumption and bladder cancer, with 594 cases and a random subcohort of 3170 participants from a large total cohort.16

Exposure variables

Lifestyle and dietary factors received much attention (19 articles), most concerning cardiovascular outcomes (table 3). Eleven articles, mainly on cancer, looked at environmental exposures; 13 looked at biochemical and physiological markers. Nine articles looked at the influence of one disease on another (for example, diabetes and heart disease). Other variables examined were socioeconomic factors (six articles), fetal growth markers (six articles), and genetic markers (five articles).

Table 3.

Types of exposure variable investigated in 73 epidemiological publications

| No of articles | |

|---|---|

| Nature of principal exposure variable: |

|

| Lifestyle |

11 |

| Environmental |

11 |

| Pre-existing condition |

9 |

| Diet |

8 |

| Biochemical |

7 |

| Physiological |

6 |

| Socioeconomic |

6 |

| Fetal |

6 |

| Genetic |

5 |

| Other |

4 |

| Statistical type of exposure variable*: |

|

| Continuous quantitative measure |

15 |

| Ordered categorisation of quantitative |

42 |

| Binary categorisation of quantitative |

9 |

| Binary (yes/no) indicator |

34 |

| Ordered categorical item |

11 |

| Unordered categorical item | 4 |

Some authors analysed principal exposure variable in more than one way.

Information collected from eligible epidemiological publications

General

Country of participants

Country of authors

Type of study design

Outcomes and exposures

Main outcomes

Specialty (for example, cancer)

Type (for example, continuous, binary)

Main risk factors

Nature (for example, lifestyle, biochemical)

Type (for example, continuous, binary)

Whether categorised

Study design

Size of study

How participants were chosen

Information on refusals

Other details for cohort studies

Length of follow up

Losses to follow up

Other details for case-control studies

Case-control ratio

Whether matched

Whether nested

Types of statistical result

Estimate (for example, odds ratio, hazard ratio)

Whether confidence intervals were given

Whether P value was reported

P value for summary's first main result (if P value was not reported it was derived from the confidence interval or the data themselves)

Adjustment for potential confounders

Reported effect modifiers/subgroup analyses

Conclusions

Study's main conclusions

Study's deficiencies

Study's strengths

Fifty articles studied quantitative exposure variables. They were commonly grouped into several ordered categories (42 articles), with the number of categories and cut points justified in 22 articles. Nine articles reported one cut point—that is, two categories. Fifteen articles used linear associations to model effects of continuous exposure: only two reported checking for linearity. Some articles presented results in two ways—for example, 11 articles analysed exposures both as continuous variables and ordered categories. Binary (yes/no) exposures were reported in 34 articles, while 15 articles reported exposures naturally in several categories, 11 with evident ordering.

Confounders

In 67 articles (92%) statistical analyses were adjusted for potential confounders. The extent of adjustment varied enormously: the median number of variables was seven, and two studies adjusted for over 20 confounders. How confounders were chosen (that is, pre-declared, selected post hoc, or statistical algorithm) was mostly unclear. Eleven articles used stepwise regression to select variables for final analysis. Twenty one case-control studies matched on other factor(s), commonly matching on two or three variables. Five articles contained no control for confounders.

Statistical estimates and inferences

Odds ratios were estimated in 38 articles, including all case-control studies (table 4). Rate ratios or hazard ratios were estimated in 22 cohort studies. Methods included proportional hazard models, Poisson models, and person years analyses. Six cohort studies reported odds ratios: two were really rate ratios, two used pooled logistic regression for time updated variables,17 and two lacked event times.

Table 4.

Principal statistical estimates for associations between exposure and outcome in 73 epidemiological publications according to study design

| Type of result | Cohort | Case-control | Cross sectional | Case-cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio |

6 |

25 |

7 |

— |

| Hazard/rate ratio |

22 |

— |

— |

1 |

| Risk ratio |

2 |

— |

1 |

— |

| Regression coefficient |

2 |

— |

— |

— |

| Other | 5 | — | 2 | — |

All but five articles used confidence intervals; 35 articles contained no P values and only 15 gave P values for all primary results. Papers in the journal Epidemiology contained no P values, according to editorial policy at the time18,19 which has since changed.20 Two articles presented neither P values nor confidence intervals, while 10 articles gave both throughout.

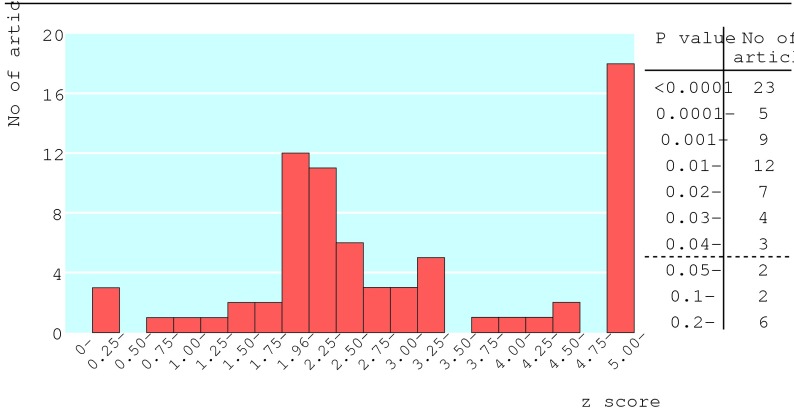

The figure shows the distribution of P values for the first reported result in each article's abstract. P values were stated in 38 articles, derived from the confidence interval in 33, and calculated from the raw data in two. Ten articles had P > 0.05, and 23 articles had P < 0.0001. Twenty six articles had 0.01 < P < 0.05—that is, their first result achieved modest significance.

Figure 1.

Distribution of P values for first primary result in each article and corresponding absolute values of standardised normal deviates z (two sided P=0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001 correspond to z=1.96, 2.58, 3.29, and 3.89, respectively)

Effect modifiers

Forty three articles contained subgroup analyses, 34 of which claimed possible effect modification. Only eight articles gave statistical tests for interaction. In one paper the result of the interaction test was not significant but the authors still claimed a synergistic interaction.21

Multiple analyses

One problem is that some articles investigated many associations between exposure and outcome,22 which are often hard to interpret as few authors predefine all study hypotheses and many selectively report “interesting” associations. Ten articles each reported over 100 estimates of the effect of exposure and outcome (the highest was 264). Some articles selectively emphasised the most significant associations, inflating the risk of false positive results through multiple hypothesis testing.

Refusals

Thirty four studies (47%) gave no information on the number of participants who refused to participate.

Discussion

Our survey into the current state of epidemiological publications in high impact journals raises concerns regarding aspects of study design, analysis, and reporting that could lead to misleading results in some publications.

Our focus on high impact epidemiological and general medical journals has by design under-represented epidemiology in the many specialist medical journals. Our sample articles may be better quality as journals that publish only occasional epidemiological articles may be less discriminating.23

We focused on epidemiological studies in general populations. We excluded studies on clinical epidemiology in people with disease and studies in pharmacoepidemiology, although they raise similar issues. The quality of published randomised controlled trials24,25 and non-randomised intervention studies26,27 have been evaluated. The corresponding paucity of surveys into epidemiological studies motivated our work.

Types of study

We have confirmed that research on cancers and cardiovascular diseases dominates published epidemiology. The originality of some such efforts has been questioned,28 and epidemiological research is lacking in many other diseases. We found few articles concerned with developing countries, though they may be published in tropical medicine journals instead.

Cohort studies were common, especially regarding cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality. Major cohort studies produce many publications: our one month's survey unsurprisingly captured the nurses health study, the Framingham study, the national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES), and the multiple risk factor intervention trial (MRFIT). Case-control studies were the appropriate chosen design for rarer outcomes—for example, cancers. Other specialties (such as mental health and diabetes) used cross sectional designs. We found only one case-cohort study.16 In such studies29,30 cases are identified from a cohort during follow up. Controls are sampled from the whole cohort, including people who become cases. The case-cohort design is logistically simpler than for case-control studies, although its analysis must handle the potential duplication of cases as controls. Their popularity may increase especially when several outcomes are investigated with large data bases.

One important question is whether a study's design is appropriate for the topic addressed. We have concentrated here on analysis and reporting, but we encourage subsequent enquiry into this key design concern.

Exposure variables

The most commonly investigated issues were lifestyle and behavioural. Genetic studies were few, though genetic epidemiology is a growing discipline.31 Most exposures were quantitative, usually grouped into ordered categories rather than analysed as continuous variables. Methodologists have emphasised the importance of appropriate selection of categories and presentational methods32-35 but few articles gave reasons for the choice of categories and analyses, raising suspicions that alternative groupings might have also been explored. Furthermore, articles generally did not discuss the quality of the data. Ad hoc categorisations and measurement errors might explain many inconsistencies in published results.14

Measures of association and inferences

Overall, authors presented appropriate estimates of their associations. Case-control studies used odds ratios, and most cohort studies used some form of rate ratio. Hazard ratios from proportional hazards models appear more often than rate ratios from Poisson models, which are appropriate only when rates stay constant over time.7 Nomenclature and methods did not always match—for example, we had to check the results and methods sections carefully to identify what authors actually meant by “relative risk” or “risk ratio”.

Confidence intervals were usually presented as appropriate expressions of statistical uncertainty, but in some papers text and tables wee made unwieldy by their excessive use. Hypothesis testing appeared in about half of articles, indicating rehabilitation of P values in observational studies.20,36,37 None the less, conclusions should not rely on arbitrary cut offs such as P < 0.05.

The distribution of P values in the figure has a peak around 0.01 < P < 0.05, suggesting that publication bias affects epidemiology, as such significant findings are presumably more publishable.38 Randomised clinical trials and observational epidemiology have different research philosophies, which may affect publication bias. Trials are more decision oriented, often studying a single primary hypothesis with a (hopefully) unbiased design. As authors of epidemiological studies have more options on what to publish, publication bias is more complex and of potentially greater concern.

Adjustment for confounders

Most authors adjusted for potential confounders, though the extent varied greatly. Though techniques for such adjustment are established, their implementation seems inconsistent. For some topics—for example, coronary heart disease—past experience aids the choice of variables, but how confounding is tackled depends on the authors' disposition and the extent of data. Few explained how and why they chose variables for adjustment. A few were overenthusiastic and included too many variables in small studies. Some used stepwise regression to reduce the set of adjustment variables, a practice not without problems.39,40 Such procedures do not consider whether a variable's inclusion in the model affects the estimated effect of the exposure—that is, whether the variable is a confounder.

Some reported both unadjusted analyses and analyses adjusted for covariates, which appropriately informs readers of the role confounders had.

Effect modifiers

Subgroup analyses were common, and half of the articles claimed some effect modification. In clinical trials41,42 and epidemiology22 overinterpretation of subgroup analyses presents three problems: increased risk of false claims of effect modification when several subgroup analyses are explored; insufficient use of statistical tests of interaction, which more directly assess the evidence for an effect modifier, compared with misleading uses of subgroup P values or confidence intervals; and the need to exercise restraint, viewing subgroup findings as exploratory and hypothesis generating rather than definitive.

Multiplicity

Some studies explore many associations without considering the consequent increased risk of false positive findings.10,22 Such “data dredging”14 biases publications towards exaggerated claims. Investigators often focus on the most significant associations. This is accentuated in cohort studies with multiple publications, where what gets published can be highly selective. Particularly in small studies, apparently strong associations may be spurious and not supported by subsequent studies.

Study size

Few studies gave any power calculation to justify their size. One proposal is that cohort studies, specifically in coronary heart disease, require over 400 events to achieve sufficiently precise estimation.43 This is around the median number of events in our cohort studies, suggesting that many are underpowered, unless the associations with risk are pronounced. For instance, a cohort study relating bone mass to risk of colon cancer had only 44 incident cases.44 With authors seeking positive findings, small studies need inflated associations between exposure and outcome to achieve significance and get published. Selective timing of publication may also increase the risk of false positives.

The methods of power calculation for case-control studies are well established.45 As they have fewer controls per case compared with the ratio of subjects without and with events in cohort studies, the desired number of cases needs to be just as large, except for detecting strong associations. Our case-control studies had a median of 347 cases, suggesting that many could detect only large effects. For instance, one study with 90 cases and controls needed to observe a steep gradient of risk of breast cancer with birth weight to reach significance.46

Sample selection

A study's representativeness depends on the source of participants and the proportion participating.47 Information on refusals and drop outs is often lacking. Authors should document the sample selection process and participation rate.

Conclusions and key findings

We have identified issues of concern surrounding the design, analysis, and reporting of epidemiological research. We think primary responsibility for improvement rests with authors, though journals and peer reviewers need to be vigilant to enhance the quality of articles.

The following limitations merit particular attention:

The participant selection process—for example, information on exclusions and refusals—often lacks details

The quality of data collected, and any problems therein, are often insufficiently described

Some studies are too small and may be prone to exaggerated claims, while few give power calculations to justify their size

Quantitative exposure variables are commonly grouped into ordered categories, but few state the rationale for choice of grouping and analyses

The terminology for estimates of association—for example, the term “relative risk”—is used inconsistently

Confidence intervals are appropriately in widespread use but were presented excessively in some articles

P values are used more sparingly, but there is a tendency to overinterpret arbitrary cut offs such as P < 0.05

The selection of and adjustment for potential confounders needs greater clarity, consistency, and explanation

Subgroup analyses to identify effect modifiers mostly lack appropriate methods—for example, interaction tests—and are often overinterpreted

Studies exploring many associations tend not to consider the increased risk of false positive findings

The epidemiological literature seems prone to publication bias

There are insufficient epidemiological publications in diseases other than cancer and cardiovascular diseases and in developing countries

Overall, there is a serious risk that some epidemiological publications reach misleading conclusions.

What is already known on this topic

Papers in observational epidemiology vary greatly in quality, content, and style

There are no generally accepted reporting guidelines for epidemiological studies

What this study adds

This study presents a survey of recent epidemiological publications.

Critical evaluation concerns: types of study design, study size, sample selection, disease outcomes investigated, types of exposure variable, handling of confounders, methods of statistical inference, claims of effect modification, the multiplicity of outcome-exposure associations explored and publication bias.

There is a serious risk that some epidemiological publications reach misleading conclusions

We are grateful to Nicole Leong for her valuable contributions to getting the study underway. We thank Diana Elbourne, Stephen Evans, and John McKinlay for helpful comments on the draft manuscript.

Contributors: All authors jointly conceived the project, undertook the survey, and contributed to writing and revising the manuscript. SJP drafted and coordinated the article's content, TJC coordinated the survey's conduct and BLdeS substantially revised the article. SJP is guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern epidemiology. Boston: Lippincott-Raven, 1998.

- 2.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol 1. The analysis of case-control studies. Lyons: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1980. [PubMed]

- 3.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol 2. The analysis of cohort studies. Lyons: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1980.

- 4.dos Santos Silva I. Cancer epidemiology: principles and methods. Lyons: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1999.

- 5.Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in medicine. Boston: Little, Brown, 1987.

- 6.Schelsselman JJ. Case-control studies: design, conduct, analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- 7.Clayton D, Hills M. Statistical models in epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- 8.Grimes D, Schulz KF. Epidemiology series. Lancet 2002;359: 57-61, 145-9, 248-52, 341-5, 431-4.11809203 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epidemiology Work Group. Guidelines for documentation of epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol 1981;114: 609-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rushton L. Reporting of occupational and environmental research: use and misuse of statistical and epidemiological methods. Occup Environ Med 2000;57: 1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blettner M, Heuer C, Razum O. Critical reading of epidemiological papers: a guide. Eur J Pub Health 2001;11: 97-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwitz RI, Feinstein AR. Methodologic standards and contradictory results in case-control research. Am J Med 1979;66: 556-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomized and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52: 377-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davey-Smith G, Ebrahim, S. Data dredging, bias, or confounding. BMJ 2002;325: 1437-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Journal Citation Reports. http://wos.mimas.ac.uk/jcrweb (accessed May 2001).

- 16.Zeegers MPA, Volovics A, Dorant E, Goldbohm RA, van den Brant PA. Alcohol consumption and bladder cancer risk: results from the Netherlands cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153: 38-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Agostino RB, Lee M-L, Belanger AJ, Cupples LA, Anderson K, Kannel WB. Relation of pooled logistic regression to time dependent Cox regression analysis: the Framingham heart study. Stat Med 1990;9: 1501-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothman KJ. Writing for epidemiology. Epidemiology 1998;9: 333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang JM, Rothman KJ, Cann CI. That confounded P-value. Epidemiology 1998;9: 7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinberg CR. It's time to rehabilitate the P-value. Epidemiology 2001;12: 288-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su LJ, Arab L. Nutritional status of folate and colon cancer risk: evidence from NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Ann Epidemiol 2001;11: 65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ottenbacher KJ. Quantitative evaluation of multiplicity in epidemiology and public health research. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147: 615-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KP, Schotland BA, Bacchetti P, Bero LA. Association of journal quality indicators with methodological quality of clinical research articles. JAMA 2002;287: 2805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. The CONSORT group. Lancet 2001;357: 1191-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff, F, Elbourne D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001;134: 663-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating nonrandomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess 2003;7: 1-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz, RI, Randomised, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Eng J Med 2000;342: 1887-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuller L H. Invited commentary: circular epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150: 897-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langholz B. Case-cohort Study. In: Gail M, Benichou J, eds. Encyclopedia of epidemiologic methods. Chichester: Wiley, 2000: 139-45.

- 30.Wacholder S. Practical considerations in choosing between the case-cohort and nested case-control design. Epidemiology 1991;2: 155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colhoun HM, McKeigue PM, Davey-Smith G. Problems of reporting genetic associations with complex outcomes: can we avoid being swamped by spurious findings? Lancet 2003;361: 865-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenland S. Analysis of polytomous exposures and outcomes. In: Rothman K J, Greenland S, eds. Modern epidemiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1998: 301-28.

- 33.Figueiras A, Cadarso-Suarez C. Application of nonparametric models for calculating odds ratios and their confidence intervals for continuous exposures. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154: 264-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao LP, Kolonel LN. Efficiency loss from categorizing quantitative exposures into qualitative exposures in case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol 1992;136: 464-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Altman DG, Lausen B, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher W. Dangers of using “optimal” cutpoints in the evaluation of prognostic factors. J Nat Cancer Inst 1994;86: 1798-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodman SN. Of P-values and Bayes: a modest proposal. Epidemiology 2001;12: 295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sterne J, Davey-Smith, G. Sifting the evidence—what's wrong with significance tests? BMJ 2001;322: 226-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higginson J. Publication of “negative” epidemiology studies. J Chron Dis 1987;40: 371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenland S, Rothman K. Introduction to stratified analysis. In: Rothman K J, Greenland S, eds. Modern epidemiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1998: 253-80.

- 40.Greenland S. Modelling and variable selection in epidemiological analysis. Am J Pub Health 1989;79: 340-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assmann SF, Pocock SJ, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis and other (mis)uses of baseline data in clinical trials. Lancet 2000;355: 1064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yusuf S, Wittes J, Probstfield J, Tyroler HA. Analysis and interpretation of treatment effects in subgroups of patients in randomized clinical trials. JAMA 1991;266: 93-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips AN, Pocock SJ. Sample size requirements for prospective studies, with examples for coronary heart disease. J Clin Epidemiol 1989;42: 639-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Felson DT, Curtis Ellison R, Kreger BE, Schatzkin A, Dorgan JF, et al. Bone mass and the risk of colon cancer among postmenopausal women. The Framingham study. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153: 31-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlesselmann JJ. Sample size. In: Case-control studies. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982: 144-70.

- 46.Kaijser M, Lichtenstein P, Granath F, Erlandsson G, Cnattingius S, Ekbom A. In utero exposures and breast cancer: a study of opposite-sex twins. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93: 60-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olson SH, Voigt LF, Begg CB, Weiss NS. Reporting participation in case-control studies. Epidemiology 2002;13: 123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]