Elderly people have a higher risk of completed suicide than any other age group worldwide.1 Despite this, suicide in elderly people receives relatively little attention, with public health measures, medical research, and media attention focusing on younger age groups.2 We outline the epidemiology and causal factors associated with suicidal behaviour in elderly people and summarise the current measures for prevention and management of this neglected phenomenon.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched Medline and the Cochrane database for original research and review articles on suicide in elderly people using the search terms “suicide”, “elderly”, and “older”.

Dispelling the myths (Greek and otherwise)

From time immemorial, suicidal feelings and hopelessness have been considered part of ageing and understandable in the context of being elderly and having physical disabilities. The Ancient Greeks tolerated these attitudes in the extreme and gave elderly people the option of assisted suicide if they could plead convincingly that they had no useful role in society. Such practices were based on the assumption that once an individual had reached a certain age then they no longer had any meaningful purpose in life and would be better off dead. Although not as extreme, ageist beliefs in modern, especially industrialised, societies are based on similar assumptions. Sigmund Freud echoed such views, while suffering from incurable cancer of the palate:

It may be that the gods are merciful when they make our lives more unpleasant as we grow old. In the end, death seems less intolerable than the many burdens we have to bear.

The burden of suicide is often calculated in economic terms and, specifically, loss of productivity. Despite lower rates of completed suicide in younger age groups, the absolute number of younger people dying as a result of suicide is higher than that for older people because of the current demographic structure of many societies.1 Younger people are also more likely to be in employment. Therefore the economic cost of suicide in younger people is more readily apparent than that in older people.

Recent developments

Elderly people have a higher risk of completed suicide than any other age group worldwide

The main psychological factors associated with suicide in elderly people include psychiatric illnesses, most notably depression, and certain personality traits

Physical factors include neurological illnesses and malignancies

The effects of physical health factors on suicide in elderly people are generally mediated by mental health factors

Social factors include social isolation and being divorced, widowed, or single

Those who have attempted suicide are at high risk of a subsequent completed suicide

The burden of suicide should not, however, be measured solely in such reductionist terms, and the extent of the real burden on families and communities from suicide in elderly people cannot be overemphasised. Furthermore, the ageing of populations worldwide means that the absolute number of suicides in elderly people is likely to increase.

Epidemiology of suicidal behaviours

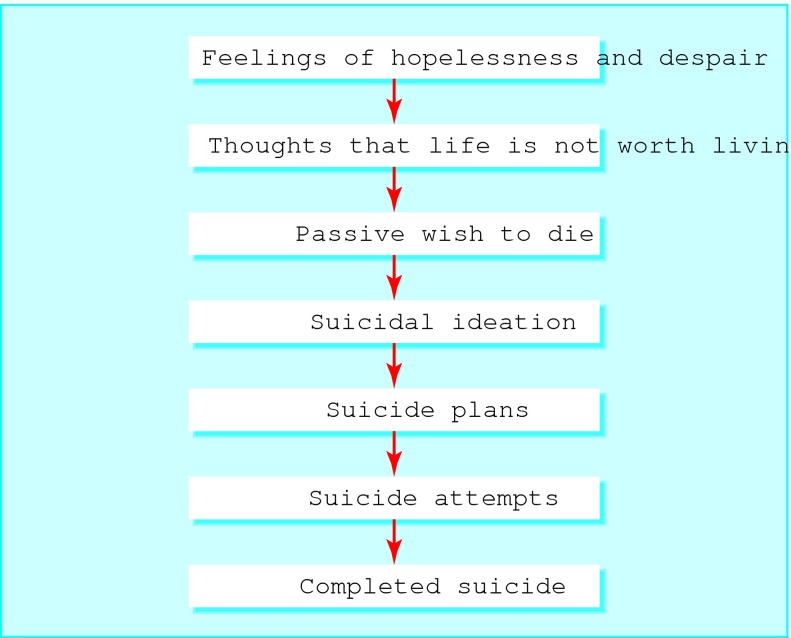

One model of the suicidal process is that suicidality exists along a continuum (figure). Following this model, the epidemiology of suicidal behaviours in elderly people can be described broadly under the headings of suicidal ideation, attempted suicide, and completed suicide.

Figure 1.

Model of suicidality

The prevalence of hopelessness or suicidal ideation in elderly people varies from 0.7-1.2% up to 17% in different studies, depending on the strictness of criteria used.3 w2 A universal finding is the strong association with psychiatric illness, particularly depression. The prevalence of suicidal feelings in mentally healthy elderly people has been reported to be as low as 4%.w3 These findings are therefore contrary to the ageist assumption that hopelessness and suicidality are natural and understandable consequences of the ageing process.

Rates of completed suicide in elderly people vary between cultures, but pooled international data published by the World Health Organization show a steady rise in prevalence of completed suicide with age. For men, the rate increases from 19.2 per 100 000 in the 15-24 year old age group to 55.7 per 100 000 in the over 75s. For women, the respective rates are 5.6 per 100 000 and 18.8 per 100 000.1 The male to female ratio for completed suicide in the elderly is 3 or 4:1, similar to that of other age groups.

Although the prevalence for completed suicide in elderly people does not at first suggest a major public health problem, completed suicides are likely to represent only the tip of the iceberg for psychological, physical, and social health problems in older people.

According to a comprehensive review of psychological autopsy studies, 71-95% of elderly people who completed suicide had a psychiatric illness, most commonly depression.4 Major depressive disorder has been found to be more common in completed suicides among older people than among younger counterparts and may affect as many as 83% of elderly people who die as a result of suicide.5 The prevalence of completed suicide is, however, relatively low among elderly people with primary psychotic illnesses, personality disorders, anxiety disorders, and alcohol and other substance use disorders.4

Data for suicidal behaviours, especially attempted suicide, between elderly and younger people suggests that different phenomena are involved.

The ratio of parasuicides to completed suicides in elderly people is much lower than that among younger people and among the general population (200:1 in adolescents, 8:1-33:1 for the general population, and 4:1 in elderly people).4 Suicidal behaviour among elderly people is therefore more likely to carry a higher degree of intent. This is further supported by the reported increased use of lethal means by older people, such as firearms and hanging.w4-w7

Factors associated with suicide in elderly people: re-examining the files of usual suspects

A wide variety of factors have been implicated in suicidal behaviour in elderly people. These can be described broadly as psychological, physical, and social factors. Such factors are either modifiable, such as physical and psychiatric illness, or non-modifiable, such as sex and social class. A description of modifiable and non-modifiable factors may provide insights into factors associated with suicidal behaviour in elderly people.

The case-control study, using psychological autopsies (information gathered after death from relatives, healthcare professionals, and medical records), is the most commonly used method for examining risk factors and associations for suicide in older people. Recent research has also focused on differences in risk factors for suicide between “young old” (under 75 years) and “old old” populations.6 w8 The importance of such research is reflected in the epidemiology of suicide in elderly people, in view of the increased risk for those aged over 75 years.1

Psychological factors

According to psychological autopsy studies of suicides in elderly people, 71-95% of the people had a major psychiatric disorder at the time of death.4 Depressive illnesses are by far the most common and important diagnoses. In the only prospective, non-clinical cohort study of older people to date in which completed suicide was the outcome, self rated severity of depressive symptoms was the strongest predictor of suicide.7 Those people in the poorest summary score category were 23 times more likely to die as a result of suicide than those with the least depressive symptoms. Other important psychological factors included drinking more than three units of alcohol a day and sleeping nine or more hours at night. The generalisability of these results is limited, however, because the people were living in a retirement community. A recently published retrospective case-control study found that alcohol use disorders predicted suicide in older people.8 A history of alcohol dependence or misuse was found in 35% of elderly men and 18% of elderly women who had died as a result of suicide, with corresponding rates in controls of only 2% and 1%.

A review summarised the findings of four psychological autopsy studies that examined the effect of psychiatric illness on completed suicide.4 Any axis I psychiatric disorder was associated with a substantially increased risk of completed suicide, with odds ratios ranging from 27.4 to 113.1. One of the studies found an odds ratio of 162.4 for recurrent major depressive disorder, with single episode major depression, dysthymia, and minor depression being important but less powerful predictors of completed suicide.9 Older people with psychotic depression may have a still further increased risk of completed suicide, although a recent study found no difference in the numbers of suicide attempts between psychotic and non-psychotic depressed elderly inpatients.w9

Other psychiatric illnesses, such as anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, and substance use disorders, have also been implicated as risk factors for suicide in elderly people, but seem to be significantly less important than depressive illnesses.4

Although three of the four studies that examined dementia diagnoses found no significant difference between people who died as a result of suicide and controls, more detailed examination of the nature and anatomical location of cerebrovascular disease is likely to provide clinically useful information in the future.4 Traditionally, an increased risk of suicide in patients after stroke was thought to be secondary to depression and functional impairment.w10 However, strategic infarcts specifically affecting frontal and subcortical circuitry have been associated with both depression and impulsivity, and the importance of cerebrovascular disease in suicidal thoughts and behaviour in older people has been argued.w11 In addition, a case-control study found that Alzheimer's disease was over-represented at autopsy in elderly people who had died as a result of suicide.w12

In keeping with findings in younger populations, significantly lower concentrations of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and homovanillic acid have been found in the cerebrospinal fluid of elderly people who died as a result of suicide compared with non-suicidal and normal controls.w13

The roles of personality type and traits have been studied in elderly people who died as a result of suicide. Clinical experience suggests that the effects of ageing on the brain, physical health problems, and life events such as bereavement may coarsen or accentuate pre-existing maladaptive personality traits in certain elderly people and make them more likely to engage in suicidal thinking or behaviour.

Elderly people who die as a result of suicide have been shown to have higher levels of neuroticism and lower scores for openness to experience, having a restricted range of interests and a comfort with the familiar.10 Interestingly, the only controlled study assessing personality disorder diagnosis, found that it was not over-represented in elderly people who died as a result of suicide.w14

A follow up study of 100 elderly people who had attempted suicide two to five years after the index attempt found that 42 had died, 12 being suspected suicides and five dying as a delayed result of the index attempt.11 Twelve women had attempted a further non-lethal attempt and five men had completed suicide after a further attempt. Recent case-control studies identified a history of a suicide attempt as a risk factor for suicide in older people.12 w15 These studies highlight the importance of secondary prevention strategies targeted at those who have attempted suicide.

Physical factors

Although problems with physical health and level of functioning are important in the cause of suicidal behaviours, controlled studies suggest that their effects are generally mediated by mental health factors, most notably depression. A recent psychological autopsy study of completed suicide in nursing home residents highlighted the complex interplay between physical and psychological factors.13

Having more than three physical illnesses and a history of peptic ulcer disease in a population sample of community dwelling residents aged over 85 years were predictive of increased suicidal feelings.w3 Physical health and disability seem to be associated independently of depression with the “wish to die.”w16 This death wish was also found to be associated with the highest comorbidity in a large sample of older patients attending their general practitioner for depression, anxiety, and at risk alcohol use.w17

Figure 2.

The Ancient Greeks had a different attitude to suicide

Credit: WOLFE COLLECTION, METROPOLITAN MUSEUM/ERICH LESSING/AKG

Based on a review of 235 prospective studies, physical disorders were associated with an increased risk of suicide, including HIV/AIDS, Huntington's disease, multiple sclerosis, peptic ulcer, renal disease, spinal cord injury, and systemic lupus erythematosus.w18 A retrospective case-control study, however, found that neither current serious physical illness nor a visit by a general practitioner in the previous month was significantly associated with completed suicide.w15 Two other retrospective case-control studies found the burden of physical illness and current serious physical illness to be significantly associated with completed suicide in elderly people.14,15 Depression was not accounted for in the first of these studies, however, and when included in the analysis in the second study, the effects of physical illness became non-significant.4 A retrospective case-control study did find that serious physical illnesses (visual impairment, neurological disorders, and malignant disease) were independent risk factors for suicide.9 The authors concluded that serious physical illness may be a stronger risk factor for suicide in men than in women, implying that elderly males may be more vulnerable to the effects of physical health problems. These findings have important implications for the detection and management of suicide in elderly people, highlighting the importance of psychiatric evaluation in people with physical disorders.

There are also important ethical implications; the fact that there is a high prevalence of potentially treatable psychiatric illness in those elderly people who have both physical illness and suicidal ideation should be central in any discussion on physician assisted suicide.

Social factors

As with other age groups, elderly people seem to have an excess of stressful life events in the weeks before suicide. The nature of these may differ in older people, with more emphasis on physical illness and losses, such as bereavement, and less emphasis on interpersonal discord, financial and job problems, and legal difficulties; these last four factors are more typically associated with suicide in younger populations.16 Some recent studies have, however, found an association between interpersonal discord and suicide, even in later life.17 w19

Decreased social support and social isolation are generally associated with increased suicidal feelings in elderly people.w17 w20 An influential study suggested that elderly people who had died as a result of suicide were more likely to have lived alone.18 More recent studies do not agree with these findings, but they did report that loneliness and low social interaction were predictive of suicide.12,17 w15

Religiosity and life satisfaction were found to be independent protective factors against suicidal ideation in elderly African-Americans.w21 Similar findings have been reported in terminally ill elderly people, where higher spiritual wellbeing and life satisfaction independently predicted lower suicidal feelings.19

In general, widowed, single, and divorced elderly people have a higher risk of suicide, with marriage seeming to be protective. Bereavement is also associated with attempted and completed suicide in elderly people—men seem especially vulnerable after the loss of a spouse, with a relative risk three times that of married men. In contrast, widowed and married elderly women seem to have a similar risk.16 A recent study concluded that the protective effect of marriage was not apparent in those aged over 80 years, showing how risk factors for suicide may differ between young old and old old.w8

Although several social factors associated with suicide in elderly people are non-modifiable, they may give clues as to the underlying biological processes involved in suicidal ideation and behaviour. For example, the increased vulnerability of elderly men to bereavement and physical illness may be mediated by relatively higher levels of cerebrovascular disease and alcohol use disorders compared with elderly women.

Figure 3.

Social isolation in elderly people can have devastating consequences

Credit: COLIN GRAY/PHOTONICA

Additional educational resources

Websites

World Health Organization (www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide)—Useful information on the epidemiology, causes, detection, screening, and management of suicide across all age groups

Royal College of Psychiatrists (www.rcpsych.ac.uk)—Information for professionals on mental health issues of older people from the college's faculty of the psychiatry of old age

National Institute Mental Health (www.nimh.nih.gov)—Information for professionals on recent advances in mental health research

Information for patients

Royal College of Psychiatrists (www.rcpsych.ac.uk)—Useful information on mental health

National Mental Health Information Center (www.mentalhealth.samhsa.gov)—Information and links for mental health issues relating to older people

Detection

Despite the higher risk of completed suicide in elderly people compared with younger age groups, the low absolute prevalence rate does not justify screening of the entire elderly population. Screening for suicidal ideation should be opportunistic, with high risk subgroups defined and targeted, based on knowledge of psychological, physical, and social factors. High risk subgroups include those with depressive illnesses, previous suicide attempts, or physical illnesses, and those who are socially isolated. Elderly people with multiple such factors warrant special attention.

Older people are less likely to volunteer that they are experiencing suicidal feelings.w22 Moreover, these feelings may be present in patients with few depressive symptoms, and feelings might not be manifest unless asked about directly. Healthcare professionals should be trained and encouraged to ask such questions directly. The presence of suicidal feelings in depressed patients also predicts a lower response to treatment and an increased need for augmentation strategies, thereby identifying a group of patients who may need secondary referral.

Management

The estimated population attributable risk for mood disorder in elderly suicide is 74%.w15 This means that if mood disorders were eliminated from the population, 74% of suicides would be prevented in elderly people. “Elimination” of mood disorders is achieved not only by treatment of existing cases but also by the prevention of new cases and secondary prevention of subclinical cases. The level of detection and treatment of depression of all ages in the general population is low, and only 52% of cases that reach medical attention respond to treatment.20,21 Detection rates and treatment response are likely to be still lower in elderly people. Thus, although treatment of depression is vital in combating suicide in elderly people, preventive measures at an individual and population level are also essential. Improved physical and emotional health, exercise, and modification of lifestyle should promote successful ageing and lead to a decrease in the incidence of suicidal feelings.

Key ongoing research

The Dublin healthy ageing study (Mercer's Institute for Research on Ageing, St James's Hospital)—a community based study examining physical, psychological, and social health factors, including an assessment of suicidal ideation, in a sample of community dwelling elderly people in Dublin

Institute of Clinical Neuroscience, Section of Psychiatry, Sahlgrenska Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden—research on suicide in elderly people carried out at this institute has contributed greatly to knowledge of the topic

Interventions at population level that improve social contact, support, and integration in the community are also likely to be effective, especially considering that the population attributable risk factor for low social contact is 27%.w15 For example, telephone help lines have been associated with a significant reduction in completed suicide in elderly people.w23

Limiting access to the means of suicide (for example, over the counter medicines) or decreasing the chance of completed suicide (for example, reducing the lethality of car exhaust fumes with catalytic converters) have been shown to have benefits for the general population and are also likely to affect suicide rates in elderly people, particularly considering the increased use of lethal means by older people.22w4-w7

An appropriate strategy for the prevention of suicide might be the introduction of opportunistic screening for hopelessness and suicidal feelings in elderly people who visit their general practitioner. This is especially important because of the high level of contact found between elderly people and their general practitioner in the week before suicide (20-50% contact) and in the month before suicide (40-70% contact).16 The Gotland study highlighted the importance of training for general practitioners to lower the incidence of suicide in all age groups.w24 Such training is also likely to lead to improved detection and management of elderly people with suicidal tendencies. A study of depression in primary care highlighted the importance of increasing doctors' awareness of depression and suicide in elderly patients.23 Compared with young adults with depression, old old (over 75 years) patients were only 6% as likely to be asked about suicide, one fifth as likely to be asked if they felt depressed, and one fourth as likely to be referred to a mental health specialist.

Conclusions

Suicide in elderly people is a complex and multifactorial phenomenon. Elderly people are frequently sidelined in discussions on suicide, perhaps as a result of factors such as a higher overall number and a higher economic burden associated with suicide in younger people and ageist beliefs about the elderly and ageing in modern, particularly industrialised, societies.

Screening, prevention, and management programmes should focus more on elderly people, in view of the inherent increased risk of suicide in this population. More specifically, there is a need for vigorous screening and aggressive treatment of depression and suicidal feelings in elderly people, especially in subgroups with additional risk factors such as those with comorbid physical illness and those who are socially isolated.

Supplementary Material

Web references w1-w24 are on bmj.com

Web references w1-w24 are on bmj.com

There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide

Albert Camus

See also Papers p 881

Contributors: HOC wrote the main body of the article under the supervision of BAL. AVC and CC provided advice on medical aspects. HOC is the guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, 2002. www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide (accessed 1 Aug 2004).

- 2.Uncapher H, Arean PA. Physicians are less willing to treat suicidal ideation in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48: 188-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirby M, Bruce I, Radic A, Coakley D, Lawlor BA. Hopelessness and suicidal ideation among the community dwelling elderly in Dublin. Ir J Psychol Med 1997;14: 124-7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry 2002;52: 193-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, Hermann JH, Forbes NT, Caine ED. Relationships of age and axis I diagnoses in victims of completed suicide: a psychological autopsy study. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153: 1001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waern M, Runenowitz E, Wilhelmson K. Predictors of suicide in the old elderly. Gerontology 2003;49: 328-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross RK, Bernstein L, Trent L, Henderson BE, Paganini-Hill A. A prospective study of risk factors for traumatic death in the retirement community. Prev Med 1990;19: 323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waern M. Alcohol dependence and alcohol misuse in elderly suicides. Alcohol Alcohol 2003;38: 249-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waern M, Runeson B, Allebeck P, Beskow J, Rubenowitz E, Skoog I, et al. Mental disorder in elderly suicides: a case-control study. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159: 450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Age differences in the personality characteristics of suicide completers: preliminary findings from a psychological autopsy study. Psychiatry 1994;57: 213-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hepple J, Quinton C. One hundred cases of attempted suicide in the elderly. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171: 42-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu HF, Yip PS, Chi I, Chan S, Tsoh J, Kwan CW, et al. Elderly suicide in Hong Kong—a case-controlled psychological autopsy study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004;109: 299-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suominen K, Henriksson M, Isometsa E, Conwell Y, Heila H, Lonnqvist J. Nursing home suicides—a psychological autopsy study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18: 1095-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conwell Y, Lyness JM, Duberstein P, Cox C, Seidlitz L, Di Giorgio A, et al. Completed suicide among older patients in primary care practices: a controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48: 23-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conwell Y, Olsen K, Caine ED, Flannery C. Suicide in later life: psychological autopsy findings. Int Psychogeriatr 1991;3: 59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cattell H. Suicide in the elderly. Adv Psychiatr Treatment 2000;6: 102-8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubenowitz E, Waern M, Wilelmson K, Allbeck P. Life events and psychosocial factors in elderly suicides—case-control study. Psychol Med 2001;31: 1193-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barraclough BM. Suicide in the elderly: recent developments in psychogeriatrics. Br J Psychiatry 1971;(suppl 6): 87-97.5576272

- 19.McClain, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual wellbeing on end of life despair in terminally ill cancer patients. Lancet 2003;361: 1603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, Wasserman D. Suicide and mental disorders: do we know enough? Br J Psychiatry 2003;183: 382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Mental health: new understanding, new hope. World health report 2001. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

- 22.Gunnell D, Frankel S. Prevention of suicide: aspirations and evidence. BMJ 1994;308: 1227-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer LR, Wei F, Solberg LI, Rush WA, Heinrich RL. Treatment of elderly and other adult patients for depression in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51: 1554-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.