Short abstract

Chronic conditions require careful management in patients who develop a life limiting illness. Doctors need to consider both the physical and psychological effects of treatment

A 68 year old woman with extensive small cell lung cancer and rapid weight loss also has long term mild hypertension with no evidence of end organ damage. What would you do about her antihypertensive treatment?

Stop drug treatment because she has a terminal illness

Continue the drugs because you would not want her blood pressure to get worse (and the conversation about stopping them may be difficult because last year you told her she would be taking these drugs for the rest of her life)

Wait until she develops postural hypotension and then consider reducing her drugs

Reduce her drugs and watch carefully.

People with progressive life limiting illnesses are often also taking drugs for treatment or prevention of long term conditions.1 However, little guidance exists to help clinicians consistently and systematically manage chronic comorbidity. Some clinicians stop drugs for chronic conditions arbitrarily because the person has a progressive life limiting illness. At the other end of the therapeutic spectrum, some clinicians do not stop any long term treatments until the patient is unable physically to take them or suffers adverse effects. Competent care for people with life limiting illnesses requires careful management of their long term drugs. We outline some key considerations.

Patients with life limiting illness

Life limiting illnesses include advanced cancer, end stage organ failure, neurodegenerative disease, and AIDS. Common conditions that need active management at the end of life include hypertension, atrial fibrillation, hypercholesterolaemia, thromboembolic disease, dementia, osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, and arrhythmia. Patients may also be taking hormone replacement therapy, immunosuppressive therapy after transplantation, or drugs to prevent opportunistic infections in people who are immunocompromised. Both the life limiting illness and comorbidity change clinically over time and therefore need regular review. What is the best way to minimise the increasing risks of long term drugs as a person's body changes with advancing life limiting illness and the known risks of polypharmacy as additional drugs are introduced to control symptoms?2

Key considerations

Current and emerging evidence can help generate a framework to improve clinical decision making for the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of common chronic conditions in patients at the end of life. The knowledge base necessary for this includes an understanding of:

Metabolism of drugs in normal and disease states

The final common pathway of involution that characterises most deaths from life limiting illness

Prognosis and natural course of the life limiting illness and comorbidities

Measure of benefit for clinical interventions—for example, number needed to treat (NNT)

Aims of intervention for comorbidity (primary, secondary or tertiary prevention?)

Psychological effects of stopping drugs.

Metabolism

The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs can change unpredictably in patients at the end of life. These changes will often heighten the effects of the drug. For example, the net effect of an antihypertensive drug may be much greater as death approaches. This is complicated by the fact that patients are often given drugs to control symptoms as the life limiting illness progresses. Polypharmacy increases the risk of drug interactions causing morbidity and potentially premature death. The risk of a serious adverse drug interaction is greater than 80% when more than seven drugs are taken.3,4

Withdrawing long term drugs for comorbidities without considering the natural course of the illness can lead to serious problems. Rebound hypertension and tachycardia may occur when α and β adrenergic blockers are withdrawn. An increase in viral load has been reported in people with AIDS when antiretroviral therapy is stopped.5

Pathophysiology of death

An understanding of what causes death should also inform treatment. In most people with a life limiting illness, death is a consequence of systemic changes rather than failure of a single organ. Homoeostasis is lost despite increasing cytokine concentrations. Altered carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism leads to a catabolic state. Cytokines, including tumour necrosis factor, interleukins 1 and 6, and interferon γ, contribute directly to the trilogy of weight loss, anorexia, and fatigue that characterise end stage disease. Loss of both adipose tissue and muscle may be severe even with little evidence of primary disease.6

Figure 1.

Comorbidity in patients with terminal illness needs careful management

Credit: JOHN COLE/SPL

The result is an irreversible and progressive process of involution as death approaches. The intake, absorption, and bioavailability of drugs change because of altered protein binding, fat storage, and volumes of distribution. Hepatic dysfunction and reduced glomerular filtration rate also affect drug metabolism and excretion. Since cachexia is progressive, frequent review of patients' drugs is needed to optimise therapeutic benefits. As a correlate, data from healthier populations with mild hypertension show that modest weight loss can allow the long term cessation of antihypertensive drugs for most people.7

Prognostication

The natural course of the life limiting illness and comorbidity affects clinical treatment. Most importantly, how does this disease behave with and without intervention? How does the disease usually progress over time? How likely is it that the course of either the life limiting illness or the comorbidity is now being influenced by the current interventions? What is the likelihood of an acute deterioration in the chronic comorbidity if treatment is reduced or withdrawn?

Prognostication is important in the decisions about management of chronic comorbidity because it frames time and influences how we respond to data on number needed to treat. For example, median and 1 or 5 year survival figures give an indication of the behaviour of the illness. Studies of doctors treating patients with life limiting illness show that clinicians inconsistently predict the absolute life expectancy but are quite accurate at predicting the remaining time in days, weeks, or months.8 The rates of change in level of function and systemic measures (weight loss, anorexia, and fatigue) are good indices of the future disease trajectory if no reversible causes are evident.

Measure of benefit

Number needed to treat is one reliable measure of benefit and burden for a specific study population over a defined treatment time.9 It represents the inverse of the absolute risk reduction for a given treatment and defines the number of people who need to be treated to avoid one event. Although number needed to treat is used almost exclusively in decisions about starting treatment, it is an overall measure of benefit and should be a factor in the continuing review of all long term drugs.

The definition of number needed to treat is not standardised for time. Standardising number needed to treat with a time frame (patient/years or patient/days of treatment to avoid one event) would make it easier to compare interventions for the same condition. In the setting of life limiting illness, the number needed to treat for a given treatment for a comorbidity will increase as the prognosis decreases, although this relation is unlikely to be linear. You need to treat a larger number of people if the time in which you want to avoid a given adverse event is shorter. For example, consider a 10 year study of an antihypertensive drug that determined the number need to treat to prevent one stroke was 25. A person with advanced lung cancer and a life expectancy of six months is unlikely to reach the 10 year time point that predicted the number needed to treat of 25; the number needed to treat to prevent one stroke in six months will be much higher.

Aims of intervention

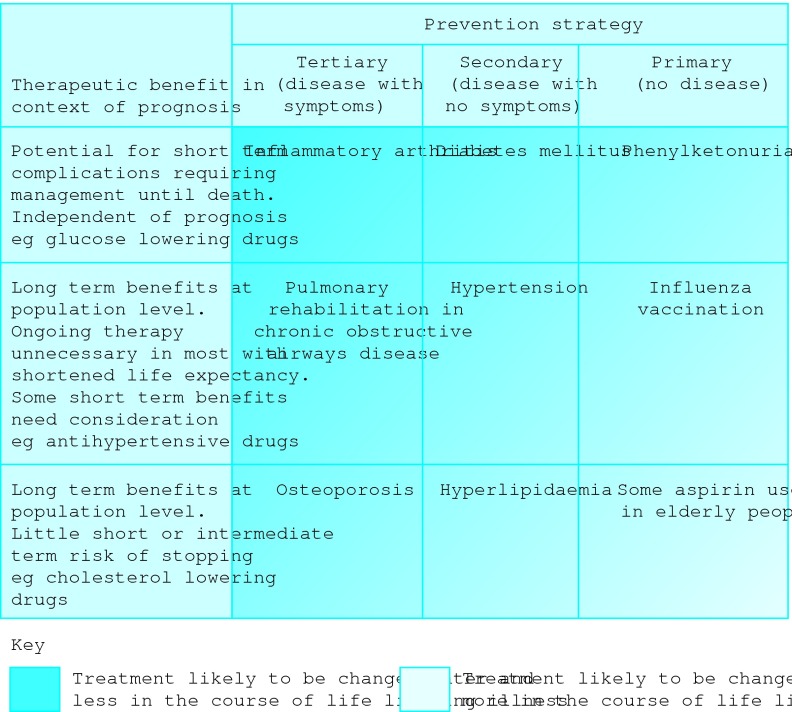

The therapeutic aim of treating comorbidities has to be clear to decide how aggressively to treat them. Very few people take long term drugs for primary prevention (no disease present). Many people are treated for secondary prevention (disease present but no symptoms). Tertiary prevention minimises the effect of a disease that is causing symptoms.10 Tertiary prevention tends to have a lower number needed to treat than primary prevention for the same clinical condition. For example, in diabetes, the number needed to treat with tight glycaemic control to prevent nephropathy over five years is 83. To limit the progression of asymptomatic, established nephropathy, it is 48.11 Tight glycaemic control increases the risk of adverse effects such as hypoglycaemia, and that can be reflected in the number needed to harm. About one in three people treated with tight glycaemic control will develop life threatening hypoglycaemia in five years.12,13 Similar data can be derived for other long term conditions such as hypertension.14-18 Drugs prescribed for tertiary prevention of a disease are likely to be continued further into the course of the life limiting illness than those prescribed for secondary prevention of the same disease (figure).

Figure 2.

Factors influencing the likelihood of continuing treatment for medical comorbidities in patients with life limiting illness, and examples of conditions in each category

Psychological concerns

The psychological sequelae of stopping long term treatments are not well researched. One third of patients completing adjuvant chemotherapy for stage 2 or 3 breast cancer felt sad that a “safety net ” had been lost, while 10-15% suffered depression.19 Stopping cancer therapy has also been described as a crisis similar to receiving the original diagnosis.20 Similar problems may occur when stopping treatments for other conditions. The effect of stopping drugs may be reflected in the difficult conversations encountered when this is discussed (table).

Table 1.

Patients' potential perceptions and clinicians' potential responses when discussing changes to drugs for long term comorbidity in response to a life limiting illness.

| Patients' perceptions | Clinicians' potential response |

|---|---|

|

Inconsistent advice leading to difficulties with trust |

|

| “But my other doctor told me I should never stop this drug Are you saying (s)he was wrong? Do you know what you're doing?” |

“I am carefully monitoring the changes that are occurring in your body as a result of your life limiting illness. All drugs (even those for life) need to be reviewed regularly” |

|

Further conformation with mortality |

|

| “I was told to take this until I die. Are you saying I'm about to die?” |

“I am not making these changes because you are suddenly dying right now. However, there are lots of changes taking place in your body and your body is not going to tolerate this drug without more side effects” |

|

Feelings of abandonment by the medical world |

|

| “So it's not worthwhile treating me anymore.” |

“I am not going to abandon you. I will continue to treat you, focusing on maximising your comfort and independence, and minimising side effects from the drugs you are on” |

|

Exposure to the complications of the medical condition |

|

| “But won't I get sick without the tablet?” |

“The likelihood is that the tablet will now start to cause you more problems than it has in the past. Reducing the dose will keep pace with the changes you have noticed in your body” |

|

A sense of futility of previous efforts with compliance |

|

| “So why did I bother with jabbing my finger and eating rabbit food for the last twenty years?” | “The care and energy that you have put into managing your condition is an important reason for it not causing you more problems in the past. We are now focusing on a situation where there are changes in your body and the goals of managing your (comorbidity) need to change with that” |

Conclusions

Every clinician is responsible for the quality use of medications. In the face of life limiting illness, the combination of drugs for symptom control and long term comorbidities creates specific challenges for which little guidance exists. Decisions to adjust drugs should be taken actively as whole body changes occur in life limiting illness, rather than in response to adverse effects. Patients require ongoing clinical assessments that incorporate an understanding of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, pathophysiology, prognosis, number needed to treat, and the aims of treatment within the context of patient choices and best clinical practice (see bmj.com). Research is needed to explore the psychological effect of changing long term drugs or redefining long term care goals. We also need to develop a way of standardising number needed to treat over time, incorporating the non-linear aspects of this measure, to allow comparisons between the benefits and burdens of treatment for chronic conditions in patients with life limiting illness.

Summary points

Managing comorbid conditions in patients with life limiting illness requires active review to balance the problem of diminishing benefits with increasing side effects

Weight loss and other systemic changes reduce the need for many long term drugs or alter their metabolism

Some long term drugs should be continued until death while others should be ceased as systemic changes occur

Data on number needed to treat can be used to inform decisions about stopping long term treatments

As prognosis worsens for a given condition, number needed to treat increases

Supplementary Material

Illustrative clinical scenarios are presented on bmj.com

Illustrative clinical scenarios are presented on bmj.com

Contributors and sources: DCC and APA are currently leading a national project looking at the evidence base for clinical practice in palliative care. Their clinical practice includes people from a wide range of clinical backgrounds at the end of life(caresearch.com.au). CM is a general physician, much of whose practice deals with chronic complex illness. JS is a registrar doing advanced training in palliative medicine. DCC and APA were responsible for the conception and design of this article. CM and JS contributed to drafting the article and revising it critically. DCC is the guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Coebergh JW, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Post PN, Razenberg PP. Serious comorbidity among unselected cancer patients newly diagnosed in southeastern part of the Netherlands in 1993-1996. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52: 1131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, Anderson TE, Mitchell AA. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States. JAMA 2002;287: 337-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg RM, Mabee J, Chan L, Wong S. Drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in the ED: analysis of a high-risk population. Am J Emerg Med 1996;14: 447-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannesse CK, Derkx FHM, De Ridder MAJ, Man in't Veld AJ, Van der Cammen TJM. Contribution of adverse drug reactions to hospital admission of older patients. Age Ageing 2000;29: 35-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colven R, Harrington RD, Spach DH, Cohen CJ, Hooton TM. Retroviral rebound syndrome after cessation of suppressive antiretroviral therapy in three patients with chronic HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 2000;133: 430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotler DP. Cachexia. Ann Intern Med 2000;133: 622-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Applegate WB, Ettinger WH Jr, Kostis JB, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomised controlled trial of nonpharmacological interventions in the elderly (TONE). JAMA 1998;279: 839-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, Hidson M, Eychmuller S, Simes J, et al. A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 2003;327: 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Eng J Med 1988;318: 1728-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hensrud DD. Clinical preventive medicine in primary care: background and practice: 1. Rationale and current preventive practices. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75: 165-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993;329: 977-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Adverse events and their association with treatment regimens in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care 1995;18: 1415-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998;352: 837-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guidelines Subcommittee. World Health Organisation-International Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. J Hypertens 1999;17: 151-83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. Lancet 2000;355: 1955-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2000;342: 145-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Progress Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2001;358: 1033-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsen H, Klemstrud T, Stokke HP, Tretli S, Westheim A. Adverse drug reactions in current antihypertensive therapy: a general practice survey of 2586 patients in Norway. Blood Press 1999;8: 94-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward SE, Viergutz G, Tormey D, de Muth J, Paulen A. Patient's reactions to completion of adjuvant breast cancer therapy. Nursing Research 1992;41: 362-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnold EM. The cessation of cancer treatment as a crisis. Soc Work Health Care 1999;29: 21-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.