Abstract

Anguibactin, a siderophore produced by Vibrio anguillarum, is synthesized via a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) mechanism. We have identified a gene from the V. anguillarum plasmid pJM1 that encodes a 78-kDa NRPS protein termed AngM, which is essential in the biosynthesis of anguibactin. The predicted AngM amino acid sequence shows regions of homology to the consensus sequence for the peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) and the condensation (C) domains of NRPSs, and curiously, these two domains are not associated with an adenylation (A) domain. Substitution by alanine of the serine 215 in the PCP domain and of histidine 406 in the C domain of AngM results in an anguibactin-deficient phenotype, underscoring the importance of these two domains in the function of this protein. The mutations in angM that affected anguibactin production also resulted in a dramatic attenuation of the virulence of V. anguillarum 775, highlighting the importance of this gene in the establishment of a septicemic infection in the vertebrate host. Transcription of the angM gene is initiated at an upstream transposase gene promoter that is repressed by the Fur protein in the presence of iron. Analysis of the sequence at this promoter showed that it overlaps the iron transport-biosynthesis promoter and operates in the opposite direction.

Iron is an essential element for nearly all microorganisms, and bacteria have evolved systems, such as siderophores, to scavenge ferric iron from the environment and in particular from the iron-binding proteins of their hosts (11, 12, 40). Siderophores are low-molecular-weight iron chelators (17, 25, 40), and the systems include the biosynthetic machinery to assemble the siderophores and the specific membrane receptors and transport protein complexes that recognize the ferric siderophore (11, 23). These systems are tightly regulated in their expression by the concentration of free iron in the environment. Thus, once synthesized under conditions of iron limitation, secreted siderophores act as extracellular solubilizing agents for organic compounds or minerals.

Vibrio anguillarum is the causative agent of vibriosis (3), a terminal hemorrhagic septicemia in salmonid fishes, and many isolates of this bacterium possess a plasmid-mediated iron uptake system that has been shown to be essential for virulence (18, 58). Our laboratory has recently reported the complete sequence of the 65-kb virulence plasmid pJM1 of V. anguillarum strain 775(18). This plasmid harbors most of the genes encoding the proteins for the biosynthesis of the 348-Da siderophore anguibactin as well as those involved in recognition of the ferric-anguibactin complex and transport of iron into the cell cytosol (2, 4, 21, 48). Anguibactin belongs to a unique structural class of siderophores that possess both a catechol and a hydroxamate group, and it has been characterized as a ω-N-hydroxy-ω-N[(2′-[2",3"-dihydroxyphenyl]thiazolin-4′-yl)carboxy]histamine by crystal X-ray diffraction studies and chemical analysis (1, 28). We predict that anguibactin is synthesized from 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid, cysteine, and histamine. Indeed, recent investigations demonstrated that both 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid and histamine are required for the biosynthesis of this siderophore (15, 49, 55).

Proteins belonging to the nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) family are a hallmark in the biosynthesis of peptide siderophores (20, 22, 35, 36). NRPSs synthesize peptide siderophores or antibiotics in the absence of an RNA template via a multistep process (32, 37, 51). Diverse peptide structures are derived from a limited number of catalytic domains of NRPSs. Sets of catalytic domains constitute a functional module containing the information needed to complete an elongation step in peptide biosynthesis. Each module combines the catalytic functions for activation by ATP hydrolysis of a substrate amino acid, for transfer of the corresponding adenylate to the enzyme-bound 4′-phosphopantetheinyl cofactor, and for peptide bond formation. A classic module thus consists of an adenylation (A) domain, a peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) domain, and a condensation (C) domain, with additional domains that could lead to modification of the substrates if required in the synthesis of the peptide (34, 47, 52). In V. anguillarum, we have already characterized two of the anguibactin biosynthetic proteins, AngR and AngB, as NRPSs (55, 57).

A mutant was isolated from a transposon insertion collection that did not produce anguibactin. In this work, we characterized the mutated gene, designated angM, revealing that it encodes a novel NRPS that harbors only PCP and C domains. Mutagenesis and complementation studies demonstrated that AngM is essential for the biosynthesis of anguibactin and for the virulence of V. anguillarum in the fish host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. V. anguillarum was cultured at 25°C in either Trypticase soy broth or agar supplemented with 1% NaCl (TSBS and TSAS, respectively). For experiments determining iron uptake characteristics, the strains were first grown on TSAS supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and passaged to M9 minimal medium (43) supplemented with 0.2% Casamino Acids, 5% NaCl, appropriate antibiotics, and either various concentrations of ethylenediamine-di-(o-hydroxyphenyl acetic acid) (EDDA) for iron-limiting condition or 2 μg of ferric ammonium citrate per ml for iron-rich conditions. The antibiotic concentrations used for V. anguillarum were ampicillin at 1 mg/ml, tetracycline at 5 μg/ml, rifampin at 100 μg/ml, chloramphenicol at 10 to 15 μg/ml, and gentamicin at 10 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Vibrio anguillarum | ||

| 775(pJM1) | Wild type | 19 |

| H775-3 | Plasmidless derivative of 775 | 19 |

| 775MET11(pJM1) | Fur-deficient mutant of 775(pJM1) | 56 |

| CC9-16(pJHC9-16) | Anguibactin deficient, iron transport proficient | 53 |

| CC9-8(pJHC9-8) | Anguibactin deficient, iron transport deficient | 53 |

| 775(pJM1::63) | 775 carrying pJM1 with Tn3::Ho-Ho1 insertion in angM | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| XL1 Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA46 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA lac F′ [proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| HB101 | supE44 hsd20 (rB− mB−) recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 | 10 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJM1 | Indigenous plasmid in strain 775 | 19 |

| pJHC-T7 | Recombinant clone carrying a 17.6-kb region of pJM1 cloned in pVK102, Tcr | 48 |

| pJHC-T7::63 | pJHC-T7 with a Tn3::Ho-Ho1 insertion in angM, Tcr, Apr | 48 |

| pJHC9-8 | pJM1 derivative carrying only the TAF region | 48 |

| pJHC9-16 | pJM1 derivative carrying TAF and transport genes | 48 |

| pPH1JI | Plasmid with RP4 ori, incompatible with pJHC-T7, Gmr | 27 |

| pRK2073 | Helper plasmid for conjugation, Tpr Tra+ | 24 |

| pBluescript SK+ | Cloning vector, Apr | Stratagene |

| pCR®-BluntII-TOPO® | Cloning vector, Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pBR325 | Cloning vector, Tcr Cmr Apr | 9 |

| pBR325-M200 | Cloning vector derived from pBR325, Tcr Cmr Aps | This study |

| pKK232-8 | Cloning vector carrying a promoterless cat gene Apr | Pharmacia |

| pMDL4 | 2.5-kb PCR fragment from pJM1 cloned in pCRBluntII-TOPO | This study |

| pMDL4-S215A | pMDL4 with mutation S215A in PCP domain | This study |

| pMDL4-H406A | pMDL4 with mutation H406A in C domain | This study |

| pMDL21 | BstEII-NheI fragment from pMDL4 cloned in pBR325-M200 | This study |

| pMDL21-S215A | BstEII-NheI fragment from pMDL4-S215A cloned in pBR325-M200 | This study |

| pMDL21-H406A | BstEII-NheI fragment from pMDL4-H406A cloned in pBR325-M200 | This study |

| pECO13 | 1.9-kb EcoRI fragment from pJM1 cloned in pBluescript SK+ | This study |

| pKKE13 | BamHI-HindIII fragment from pECO13 cloned in pKK232-8 | This study |

| pKKE13-1 | PstI-AatII deletion of pECO13 cloned in pKK232-8 | This study |

| pKKE13-2 | PstI-BstEII deletion of pECO13 cloned in pKK232-8 | This study |

| pKKE13-3 | PstI-HpaI deletion of pECO13 cloned in pKK232-8 | This study |

| pSC25 | 421-bp SalI-PvuI fragment of fatB cloned in pBluescript SK+ | This study |

| pMN5 | 102-bp BamHI-BstXI fragment of angM cloned in pBluescript SK+ | This study |

| pQSH6 | 415-bp SalI-ClaI fragment of aroC cloned in pBluescript SK+ | This study |

Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium in the presence of the appropriate antibiotics. The antibiotic concentrations used for E. coli were ampicillin at 100 μg/ml, tetracycline at 10 μg/ml, chloramphenicol at 30 μg/ml, gentamicin at 10 μg/ml, and trimethoprim at 10 μg/ml.

General methods.

Plasmid DNA was prepared with the alkaline lysis method (8). Sequence-quality plasmid DNA was generated with the Qiaprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen) and Wizard Plus SV minipreps (Promega). Restriction endonuclease digestion of DNA was performed under the conditions recommended by the supplier (Invitrogen, Roche, and New England Biolabs). Transformations in E. coli strains HB101 and XL1 Blue and other cloning strategies were performed according to standard protocols (43). DNA sequencing reactions were carried by the OHSU-MMI Research Core Facility (http://www.ohsu.edu/core) with an Applied Biosystems Inc. model 377 automated fluorescence sequencer. Manual sequencing was performed by the dideoxy chain termination method with the Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (U.S. Biochemicals) with appropriate primers. Sequencing primers were designed with Oligo 6.8 primer analysis software and purchased from the OHSU-MMI Research Core Facility (http://www.ohsu.edu/core) and Invitrogen. DNA and protein sequence analyses were carried out at the NCBI with the BLAST network service and also with the Sequence Analysis Software Package of the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group (GCG). The GCG programs Pileup and Bestfit were used for comparisons of amino acid sequences.

Construction of the complementing clone.

A 2.5-kb fragment containing the angM gene was amplified by PCR with the AngM-F (5′-TAACGGAGTGGAAATCTGAGTC-3′ ) and AngM-NheIR (5′-GACTCAATGCCACATGCAACTGTAC-3′) primers and pJM1 as a template. Reactions consisted of 4 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 3 min at 72°C, followed by a single cycle at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR product was cloned in the pCR-BluntII-TOPO vector with the Zero Blunt TOPO PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen), resulting in plasmid pMDL4. A BstEII (blunt)-NheI fragment from pMDL4 was subcloned into the ClaI (blunt) and NheI sites of pBR325-M200 to generate plasmid pMDL21 carrying the angM gene. After recloning in pBR325-M200, the entire angM gene was sequenced to verify that no mutation was generated in the angM gene during amplification or cloning. The pBR325-M200 cloning vector was derived from pBR325 by digestion with PstI, filling in of the ends with Klenow (Roche), and religation, resulting in inactivation of the ampicillin resistance gene.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Plasmids pMDL4-S215A and pMDL4-H406A were generated with the Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The template used in this experiment was pMDL4, which contains the angM gene. Primers S215A-F (5′-GATTCTTGTTGCTAATAACGCGTGACCACCCATTTC-3′) and S215A-R (5′-GAAATGGGTGGTCACGCGTTATTAGCAACAAGAATC-3′) were used for the mutation in the PCP domain, and primers H406A-F (5′-AGTTTTATCTTTCCTAATCCATGCAATGATTATTGATGAATG-3′) and H406A-R (5′-CATTCATCAATAATCATGCATGGATTAGGAAAGATAAAACT-3′) were used for the mutation in the C domain. The whole procedure was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations, with 16 cycles that consisted of 30 s at 95°C, followed by 1 min at 55°C and 12 min at 68°C. For the amplification, Pfu polymerase was used, and after the PCR, the mixture was treated with DpnI to cleave the parental DNA. Then 1 μl of the mixture was transformed into the XL1 Blue chemically competent cells provided with the Quickchange kit. Site-specific mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing with the appropriate primers. Once mutated, a BstEII (blunt)-NheI fragment from each derivative was subcloned into the ClaI (blunt) and NheI sites of pBR325-M200 to generate plasmids carrying angM derivatives with mutations in the PCP and C domain listed in Table 1. After recloning in pBR325-M200, the entire angM mutant genes were sequenced to verify that no other region of angM was affected during mutagenesis or cloning.

Construction of promoter fusions in pKK232-8.

The 1.9-kb EcoRI fragment from pJM1 harboring the transposase (tnpA1) gene of the ISV-A1 sequence and the beginning of the angM gene was cloned in the EcoRI site of pBluescript SK+, generating plasmid pECO13. Plasmid pECO13 was used to generate nested deletions, and the full-length EcoRI fragment as well as each deletion were subcloned from pECO13 and derivatives by BamHI-HindIII digestion and ligation in the corresponding sites in pKK232-8. Each construct in pKK232-8 was sequenced to verify the sequence of the insertion.

Construction of V. anguillarum strains by conjugation and allelic exchange.

Plasmids were transferred from E. coli to V. anguillarum by triparental conjugation as previously described (48).

To generate strain 775(pJM1::63), plasmid pJHC-T7::63 was transferred to V. anguillarum 775 by conjugation. In a second conjugation, plasmid pPH1JI, whose origin of replication is incompatible with the replicon of pJHC-T7::63, was transferred to the strain obtained from the first conjugation. By plating in the presence of gentamicin (the resistance marker of pPH1JI) and ampicillin (the resistance gene harbored by Tn3::HoHo1), it was possible to select cells in which the angM gene with the Tn3::HoHo1 insertion had replaced the wild-type gene on plasmid pJM1. The loss of pJHC-T7 was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization with the pVK102 vector sequence for probing (data not shown).

Growth in iron-limiting conditions and detection of anguibactin.

For mutant and wild-type strains, we determined the MIC of EDDA with liquid cultures at increasing concentrations of EDDA (1, 2, 5, and 10 μM) in M9 minimal medium at 25°C. From these analyses, we chose a concentration of 2 μM EDDA to assay for the ability of all the strains to grow in iron-limited conditions.

The siderophore anguibactin was detected by the chrome azurol S (CAS) assay and by bioassays with strains CC9-16 and CC9-8 as previously described (55, 57).

Fish infectivity assays.

Virulence tests were carried out on juvenile rainbow trout (Salmo gairdnerii) weighing ca. 2.5 to 3 g which were anesthetized with tricaine methane sulfonate (0.1 g/liter). A total of 50 anesthetized fish were inoculated intraperitoneally with 0.05 ml of each bacterial dilution, i.e., 50 fish per bacterial dilution. The dilutions were prepared with saline solution from 16-h cultures grown at 25°C in TSBS containing antibiotics for selection of the plasmids harbored by the strains. The dilutions were prepared to test a range of cell concentrations from 102 to 108 cells/ml per strain. Therefore, 350 fish were tested per strain. After bacterial challenge, test fish were maintained in fresh water at 13°C for 1 month, and mortality was checked daily. Virulence was quantified as the 50% lethal dose (LD50) (mean lethal dose; the number of microorganisms that will kill 50% of the animals tested) as determined by the method of Reed and Muench (41).

CAT assay.

V. anguillarum strains were cultured into either minimal medium supplemented with 0.5 μM EDDA (iron-limiting conditions) or minimal medium supplemented with 2 μg of ferric ammonium citrate (iron-rich conditions) per ml with the appropriate antibiotics and grown to an optical density of 0.3 to 0.5 at 600 nm (OD600). A commercial chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Roche) was used, and 1-ml samples of total proteins were prepared from each culture following the supplier's instructions. All samples were normalized for total protein levels prior to assay. All assays were repeated at least three times.

RNA isolation.

A 1:100 inoculum from an overnight culture was grown in minimal medium with appropriate antibiotics. Cultures were grown with 2 μg of ferric ammonium citrate (iron-rich) per ml or with EDDA (iron-limiting) added to achieve similar levels of iron-limiting stress for each strain tested (see the figure legends). Total RNA was prepared when the culture reached an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.5 with the RNAwiz (Ambion) isolation kit, following the manufacturer's recommendation.

Primer extension.

The primer extension experiment was carried out with the synthetic primer PEX-tnp (5′-CATCTATGGCTGAATCATCTATCC-3′), which is complementary to the 5′-end region of the tnpA1 gene. The primer was end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Life Technologies, Inc.) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and annealed to V. anguillarum 775 total RNA (50 μg). Reverse transcription from the primer with avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) and electrophoresis on a urea-polyacrylamide (6%) gel were carried out as previously described (14). Manual sequencing was performed by the dideoxy chain termination method with the Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (U.S. Biochemicals), plasmid pSC25 as the template, and primer Seq1762 (5′-GTGTACTATTGGTGCGAGC-3′).

RNase protection assays.

Labeled riboprobes were generated by in vitro transcription of 1 μg of the linearized DNA with T7 or T3 RNA polymerase (Maxiscript by Ambion) in the presence of [α-32P]UTP with pMN5 (linearized with XhoI) as a template for angM and QSH6 (linearized with RsaI) as a template for aroC. The probes were gel purified on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. For each probe, the amount corresponding to 4 × 105 cpm was mixed with each RNA sample (20 μg). RNase protection assays were performed with the RPA III (Ambion) kit following the supplier's instructions. The aroC riboprobe was used in each reaction as an internal control for the amount and quality of RNA.

RESULTS

Sequencing and analysis of a transposon insertion in the angM gene.

A collection of biosynthetic and transport mutants were generated by insertional mutagenesis with transposon Tn3::HoHo1 in the recombinant clone pJHC-T7 (48), which contains a stretch of DNA from plasmid pJM1 with iron uptake genes involved in anguibactin biosynthesis and transport. We sequenced one of these transposon mutants, pJHC-T7::63, that is deficient in anguibactin production and found that the site of Tn3::HoHo1 insertion is within the 2,145-bp open reading frame (ORF) that we named angM. The insertion occurred 438 bp from the 3′ end of angM, which is predicted to encode a polypeptide of 715 amino acids, with a calculated molecular mass of about 78 kDa (GenBank accession number AAA81775) (21).

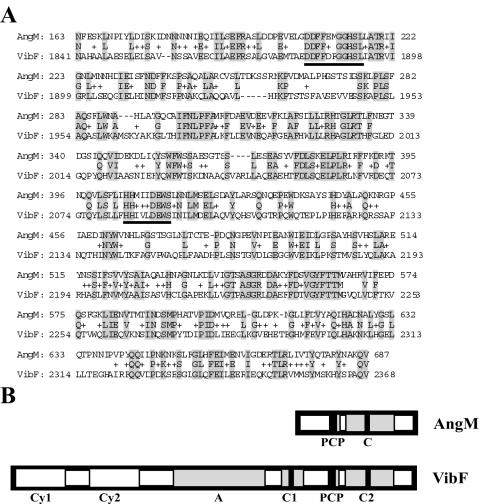

Homology searches of the DNA and the protein databases with the BLAST search engine (5) produced significant matches with other polypeptides involved in the biosynthesis of siderophores, such as VibF of Vibrio cholerae, PhbH of Photorhabdus luminescens, and DhbF of Bacillus subtilis. As shown in Fig. 1A, AngM shows 58% similarity and 39% identity with a stretch of 209 amino acids within the sequence of the V. cholerae six-domain NRPS VibF, which is required for vibriobactin biosynthesis (13). The AngM protein sequence possesses domains highly homologous to the PCP and C domains of NRPSs. However, no sequence corresponding to the A domain, which is usually found adjacent to the PCP domain, was identified in AngM (Fig. 1B). The PCP and C domains in AngM are located at positions 196 to 248 and 279 to 569, respectively.

FIG. 1.

A. Amino acid sequence alignment of AngM from V. anguillarum and VibF from V. cholerae. The consensus sequence of the highly conserved motifs of the PCP and C domains is underlined. B. Alignment of AngM domains with the domains of VibF.

Construction of an angM mutant in plasmid pJM1 and complementation with the cloned angM gene.

To discard any possible effect of the copy number of the recombinant clone pJHC-T7 (8 to 10 copies per cells) originally used to generate mutant 63, the 63 insertion mutant was integrated by allelic exchange onto the angM gene on plasmid pJM1, resulting in V. anguillarum 775(pJM1::63). The site of Tn3::HoHo1 insertion in pJM1::63 was confirmed to correspond to the same site of insertion in pJHC-T7::63 by sequencing. Strain 775(pJM1::63), harboring the insertion in the angM gene on plasmid pJM1, was tested for its ability to grow in iron-limiting conditions. The results shown in Fig. 2 demonstrated that this strain was indeed impaired in its growth under iron-limiting conditions, behaving like the plasmidless strain derivative of V. anguillarum 775, H775-3 (18).

FIG. 2.

Ability of V. anguillarum strains to grow under iron limitation is expressed as a percentage of the growth in 2 μM EDDA normalized to the growth in iron-rich conditions (2 μg of ferric ammonium citrate per ml) for each strain. The results are the means of five independent experiments, with the error bars showing standard deviations. Anguibactin production for each of these strains, as detected on CAS plates, is shown below the graph.

For complementation analyses, expression of the angM gene was placed under the control of the tetracycline resistance gene promoter of the pBR325 vector by cloning a PCR product encompassing the complete angM gene as a BstEII (blunt)-NheI fragment in the ClaI (blunt) and NheI restriction sites in pBR325-M200 to generate plasmid pMDL21. Plasmid pMDL21 was introduced by triparental mating into V. anguillarum 775(pJM1::63), and growth of the mutant strain and its complemented derivative was determined in the presence of the iron chelator EDDA at a concentration of 2 μM with the wild-type strain harboring pJM1 and the empty vector (pBR325) as a positive control.

Figure 2 shows that the mutant strain, V. anguillarum 775(pJM1::63/pBR325-M200), did not grow at this EDDA concentration, while the complemented strain, 775(pJM1::63/pMDL21), grew to wild-type levels under these conditions. Therefore, the presence of an intact angM gene is required for growth under iron-limiting conditions. Consistent with the results of the growth experiment, the mutant strain did not produce anguibactin, as determined by CAS plate assays (Fig. 2) and bioassays (data not shown), while complementation resulted in a level of anguibactin that was comparable to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2).

It is clear that the ability conferred by angM on V. anguillarum to grow under iron-limiting conditions is due to an essential role in anguibactin biosynthesis.

PCP and C domains of AngM are essential for anguibactin biosynthesis.

During siderophore biosynthesis, the PCP domains of NRPSs undergo covalent phosphopantetheinylation prior to attachment of the assembling siderophore. Phosphopantetheinylation occurs at a specific serine residue within the highly conserved motif (DxFFxLGGDSL) of this domain (44, 45, 54). A homologous motif including the specific serine residue (DDFFEMGGHSL) is present in the PCP domain of AngM. Therefore, we decided to replace the serine residue with an alanine to assess its influence on anguibactin production. By site-directed mutagenesis, a serine-to-alanine (S215A) mutation was generated in angM, resulting in plasmid pMDL21-S215A. This plasmid was conjugated into the 775(pJM1::63) strain. Figure 2 shows that the S215A mutation in plasmid pMDL21-S215A completely abolished the ability of this construct to complement insertion mutant 63, as determined by growth ability and CAS plate assays.

The highly conserved motif (HHxxxDGWS) of the C domain of NRPSs possesses two histidine residues, of which the second one has been shown to be essential to catalyze peptide bond formation (7). The C domain of AngM possesses this conserved motif (HHMIIDEWS). Therefore, to determine whether the second histidine residue also played an important role in anguibactin biosynthesis, we mutated it to an alanine (H406A) by site-directed mutagenesis. The mutant angM gene in pMDL21-H406A was then tested for its ability to complement the angM null mutant V. anguillarum 775(pJM1::63). As was the case for the site-directed mutation in the PCP domain, this mutation also affected the ability to complement insertion mutant 63 for anguibactin production and growth in iron-limiting conditions (Fig. 2). Analysis, by Western blot with an AngM polyclonal antibody, of the proteins synthesized by V. anguillarum 775(pJM1::63) harboring the clones containing the wild-type angM, the PCP domain S215A mutant, and the C domain H406A mutant identified a 78-kDa protein in all three strains, suggesting that the mutations did not affect the integrity of the AngM protein (data not shown).

Effect of angM mutations on the virulence phenotype of V. anguillarum 775.

Since angM mutations affected anguibactin production and growth under iron limitation, we predicted that they would also affect virulence. To determine whether expression of AngM is correlated with the virulence phenotype of V. anguillarum in the fish model of infection (18, 19), we carried out experimental infections of rainbow trout with the 775(pJM1::63) mutant and this mutant complemented by either pMDL21, pMDL21-S215A, or pMDL21-H406A. The results in Table 2 show that mutant 63, the AngM PCP domain mutant, and the AngM C domain mutant were all attenuated in virulence compared to the wild type. The LD50s for these mutants are of the same order of magnitude as the LD50 obtained with the plasmidless strain H775-3 (Table 2). Plasmid pMDL21 carrying the wild-type angM gene could complement the transposition mutant, resulting in an LD50 of the same order of magnitude as that of the V. anguillarum strain carrying pJM1.

TABLE 2.

Virulence as assessed by LD50 and relative attenuation

| V. anguillarum strain | LD50 | Attenuationa (fold) |

|---|---|---|

| 775(pJM1/pBR325) | 4.2 × 103 | 1 |

| H775-3(pBR325) | 1.9 × 105 | 44 |

| 775(pJM1::63/pBR325-M200) | 0.5 × 105 | 12 |

| 775(pJM1::63/pMDL21) | 5.2 × 103 | 1.2 |

| 775(pJM1::63/pMDL21-S215A) | 0.8 × 105 | 19 |

| 775(pJM1::63/pMDL21-H406A) | 1.1 × 105 | 26 |

Attenuation is calculated by the LD50 of each strain normalized to the LD50 of the wild- type strain.

Transcription and regulation of the angM gene.

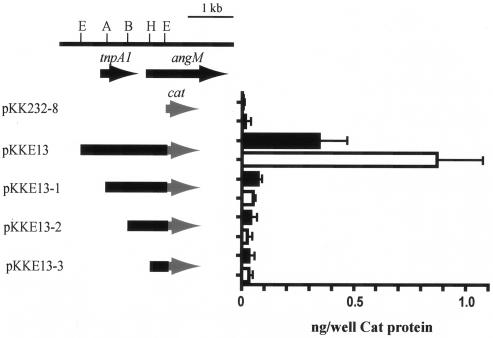

To determine the location of the promoter for the angM gene, we constructed several transcriptional fusions with the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene. The EcoRI fragment from plasmid pECO13 as well as various deletions (Fig. 3) of this fragment were cloned upstream of the promoterless cat gene of pKK232-8. Each construct was transferred by conjugation into the plasmidless derivative H775-3, and the amount of CAT protein produced by each construct in V. anguillarum was measured in iron-rich and iron-limiting conditions. The results in Fig. 3 indicate that one main iron-regulated promoter is located upstream of the transposase (tnpA1) gene of the ISV-A1 element (50). Other very weak promoters, as assessed by the level of CAT enzyme, could be identified in a region between the AatII restriction endonuclease site within tnpA1 and the beginning of angM, but these weak promoters do not seem to be iron regulated (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

CAT assay with fusions of DNA fragments spanning the region between angM and the transposase gene to a promoterless cat gene. The fragments cloned in plasmid pKK232-8 upstream of the promoterless cat gene are shown on the left-hand side of the figure. On the right-hand side of the figure, the production of CAT protein for each construct is shown as a histogram, with solid bars representing the level of CAT enzyme in iron-rich conditions (2 μg of ferric ammonium citrate per ml) and the open bars representing the level of CAT enzyme in iron-limiting conditions (0.5 μM EDDA). The CAT levels plotted are the means of three experiments, with the error bars showing standard deviations. Restriction endonucleases: E, EcoRI; A, AatII; B, BstEII; H, HpaI.

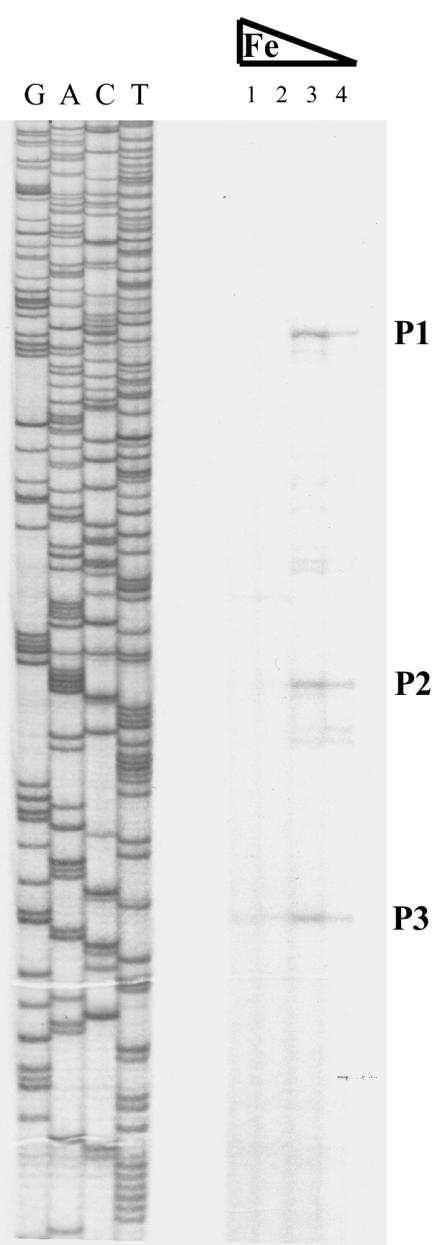

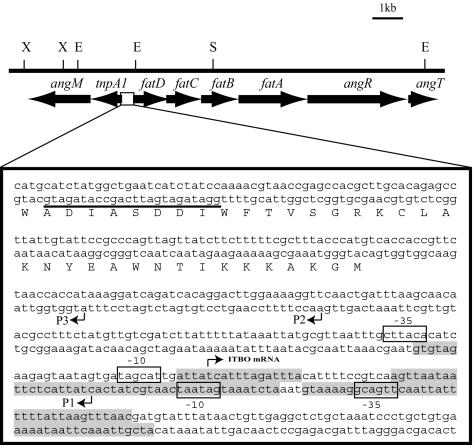

To determine the transcription start site of the tnpA1-angM mRNA, we performed a primer extension experiment with a primer (PEX-tnp) complementary to the beginning of tnpA1. The results showed three iron-regulated primer extension products (Fig. 4, P1, P2, and P3) initiated within a 121-bp region upstream of tnpA1, confirming the existence of an iron-regulated promoter for the tnpA1-angM operon. In a primer extension analysis carried out with a primer complementary to the 5′ end of the angM gene, numerous primer extension products could be identified (data not shown). These products could originate from processing of the larger mRNA encoding the tnpA1 and the genes transcribed from the transposase promoter, or they could be the result of initiation of transcription from the putative weak promoters identified in the transcriptional fusion experiments. As shown in Fig. 5, analysis of the sequence upstream of tnpA1 and of the P1 primer extension product revealed −10 and −35 sequences adjacent to the iron transport-biosynthesis operon promoter (pITBO) but in the opposite orientation (14).

FIG. 4.

Primer extension analysis with a primer at the beginning of the ISV-A1 element transposase gene and RNA obtained from cultures grown in various iron concentrations (lanes 1 to 4). Lanes G, A, C, and T represent the sequence of plasmid pCS25 with primer Seq1762. P1, P2, and P3 are putative transcription start sites for the transposase gene. Supplements to the medium: lane 1, 2 μg of ferric ammonium citrate per ml; lane 2, none; lane 3, 3 μM EDDA; lane 4, 6 μM EDDA.

FIG. 5.

Map of a 13-kb DNA region from plasmid pJM1 encoding the tnpA1 and angM genes and the pITBO. The nucleotide sequence of the region between the tnpA1 and the fatD genes is shown under the map, with the primer (underlined) used in the primer extension experiment of Fig. 4 and the locations of the putative transcription start sites (arrowheads labeled P1, P2, and P3). The −35 and −10 sequences for the P1 product and the opposite orientation −10 and −35 sequences for the ITBO mRNA are shown as open boxes, while the Fur binding sites are shown as shaded boxes. Restriction endonucleases: X, XhoI; E, EcoRI; S, SalI.

From the primer extension and cat fusion experiments, it was obvious that the transcription of angM is negatively regulated by iron at the transposase promoter. To confirm that iron regulates the expression of angM, we performed RNase protection assays with total RNA obtained from V. anguillarum 775 cultures grown under iron-rich and iron-limiting conditions. To quantify the amount of angM-specific mRNA, we used an internal fragment of the angM gene as a probe. An aroC-specific riboprobe was included in each reaction to provide an internal control for the quality of the RNA and the amount of RNA loaded onto the gel, since the aroC housekeeping gene is expressed independently of the iron concentration of the cell (15). The results shown in Fig. 6, lanes 1 and 2, demonstrated that angM gene transcription is indeed dramatically reduced under iron-rich conditions.

FIG. 6.

RNase protection assay with a probe specific for the angM gene and total RNA isolated from cultures of wild-type V. anguillarum (lanes 1 and 2) and a Fur-deficient V. anguillarum strain (lanes 3 and 4). RNA was obtained under iron-rich conditions (2 μg of ferric ammonium citrate per ml, lanes 1 and 3) or iron-limiting conditions (1 μM EDDA. lanes 2 and 4). The aroC-specific riboprobe was included in both RNase protection assays to provide an internal control for the quality of the RNA and the amount of RNA loaded onto the gel, since the aroC gene is expressed independently of the iron concentration of the cell.

To determine whether iron repression of angM gene expression is mediated by Fur, we also performed an RNase protection assay with a V. anguillarum 775 strain (775MET11) that has a null mutation in the fur gene (56). Inspection of Fig. 6, lanes 3 and 4, indicates that the angM gene is constitutively expressed in the Fur-deficient strain under both iron-rich and iron-limiting conditions, although the level of transcription appears to be reduced compared to the wild type under iron-limiting conditions (Fig. 6, lane 2). As shown in Fig. 5, the tnpA1-angM operon promoter is located within the already identified Fur binding sites that regulate expression of the pITBO (14); therefore, Fur regulates the expression of these two divergent promoters by binding to common sequences.

DISCUSSION

The iron uptake system mediated by plasmid pJM1 is an important virulence factor for the fish pathogen V. anguillarum (18). This system is composed of anguibactin, a 348-Da siderophore, and a membrane receptor complex specific for ferric anguibactin (4, 33). Besides the genes encoding the transport proteins, many genes on the virulence plasmid are part of a biosynthetic circuit in which NRPSs and tailoring enzymes result in the production of anguibactin (21).

In this work we characterized one of these essential genes, angM. Knockout of this gene dramatically affected anguibactin production and also resulted in a very significant decrease in virulence. The amino acid sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence of angM revealed a 78-kDa polypeptide harboring the PCP and C domains of NRPSs. Curiously, the A domain that is usually associated with these two domains in other NRPSs (29, 31, 34, 35, 39, 42, 46) was not identified in this protein. The amino-terminal end of the AngM protein shows no homology with any of the domains of NRPSs or any ATP-binding domain of any protein family (16, 26, 38). Although the possibility that AngM contains an atypical adenylation domain at its amino terminus cannot be discarded, the lack of any homology of the first 162 amino acids with motifs found in proteins that bind ATP strongly suggests otherwise.

Site-directed mutagenesis of S215 in the PCP domain and of H406 in the C domain of AngM resulted in an anguibactin-deficient phenotype, underscoring the importance of these two domains in the function of this protein. It is of interest that although the LD50 for mutant 63, the AngM PCP domain mutant, and the AngM C domain mutant were all of the same order of magnitude as the LD50 obtained with the plasmidless derivative H775-3, the attenuation in virulence resulting from lack of a functional AngM was about half that obtained with the cured derivative (Table 2). This difference in attenuation might be explained by considering that the cured derivative H775-3 does not produce any of the intermediaries that are produced by the angM mutants and that these products could participate in the pathogenesis of V. anguillarum. One of the products that the plasmidless derivative fails to produce is histamine (6, 49), which could play a role in amplifying the inflammatory response of the fish to the bacterial infection and result in septic shock with a smaller number of infecting bacteria.

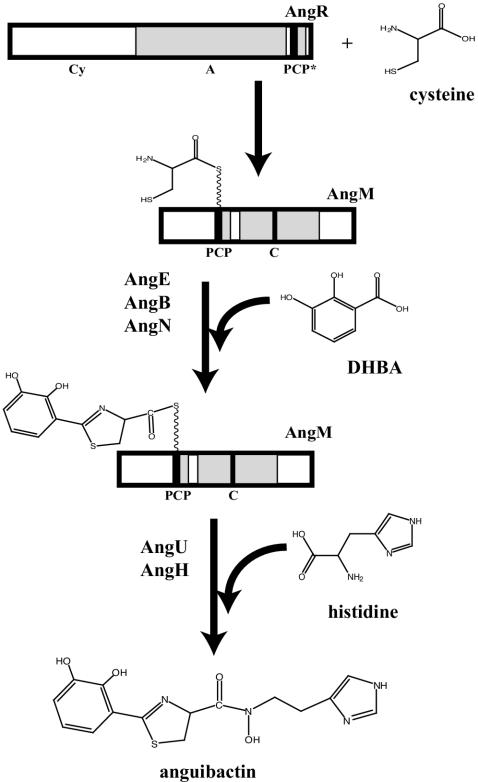

Several genes, including angM, encoding NRPSs, and tailoring enzymes were identified on plasmid pJM1 (21). It is of interest that one of them, AngR, which plays a role in regulation of the expression of iron transport genes as well as in the production of anguibactin, possesses a cyclization (Cy) domain, an A domain, and a PCP domain (57). However, in this PCP domain, the highly conserved serine present in most PCP domains (44) is replaced by an alanine. The serine residue in PCP domains is necessary for the attachment of a phosphopantetheine group for thioester formation during the process of biosynthesis. Therefore, an attractive possibility is that AngM provides an operational PCP domain, while AngR provides the A domain required to activate a substrate amino acid, possibly cysteine, prior to tethering it on the PCP domain of AngM (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Model of the biosynthetic step catalyzed by AngM. The A domain of AngR activates the cysteine, which is then tethered to the PCP domain of AngM. The C domain of AngM catalyzes peptide bond formation between the dihydroxyphenylthiazol (DHPT) group loaded on the PCP domain of AngM and the secondary amine group of hydroxyhistamine. AngE, AngB, AngN, AngU, and AngH are other NRPSs and tailoring enzymes that intervene in anguibactin biosynthesis. PCP* indicates the nonfunctional PCP domain of AngR.

We propose that the C domain of AngM catalyzes the formation of the peptide bond (41) between the dihydroxyphenylthiazolinyl group, which is still tethered to AngM, and the secondary amine group of hydroxyhistamine (Fig. 7). As in the case of VibH during vibriobactin biosynthesis (29-31), the C domain of AngM does not interact with two carrier protein domains but rather with only one upstream (the PCP domain of AngM), while the downstream substrate is the soluble non-protein-bound hydroxyhistamine. The proposed biosynthetic pathway of anguibactin is shown in Fig. 7 with the additional enzymes required.

The expression of angM at the level of transcription was repressed by high iron concentrations, and this negative regulation required the Fur protein. In the Fur-deficient strain, the angM gene is constitutively expressed, although at a reduced level. We do not know if this is a peculiarity of angM mRNA expression in the Fur mutant strain or is a more general phenomenon. Experiments to identify the mechanism responsible for this reduced expression are being carried out.

The main iron-regulated transcript was initiated at the ISV-A1 transposase promoter (50), suggesting the existence of an operon encoding the transposase and angM genes, although minor transcripts could also be initiated in a region between the tnpA1 and angM genes. The fact that angM is expressed as part of an iron-regulated operon with the upstream gene encoding a transposase is intriguing because there is no clear reason why a transposase-like protein should be expressed with an NRPS involved in siderophore biosynthesis. This operon could just be the result of a modular acquisition by the plasmid of mobile elements containing genes involved in siderophore biosynthesis as well as genes necessary for transfer of the mobile element.

Analysis of the sequence at the tnpA1-angM operon promoter shows that it overlaps the iron transport-biosynthesis operon promoter pITBO and operates in the opposite orientation. Our previous work (14) identified the region on the pITBO sequence where the Fur protein binds and determined that this interaction causes a bending of the DNA in that stretch leading to DNase I-hypersensitive sites on the complementary strand. The region that Fur binds includes the −35 and −10 sequences of the promoter of the tnpA1-angM operon, strongly supporting the idea that Fur binding leads to concerted repression of the two divergent operons.

The possibility that angM is part of a mobile genetic element and its role in the virulence of V. anguillarum 775 not only underscore the importance of this gene in the establishment of a septicemic infection in the host vertebrate but also suggest possible mechanisms for the epizootic spread of this virulence factor.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, AI19018-19 and GM604000-01, to J.H.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Actis, L. A., W. Fish, J. H. Crosa, K. Kellerman, S. R. Ellenberger, F. M. Hauser, and J. Sanders-Loehr. 1986. Characterization of anguibactin, a novel siderophore from Vibrio anguillarum 775(pJM1). J. Bacteriol. 167:57-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Actis, L. A., S. A. Potter, and J. H. Crosa. 1985. Iron-regulated outer membrane protein OM2 of Vibrio anguillarum is encoded by virulence plasmid pJM1. J. Bacteriol. 161:736-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Actis, L. A., M. E. Tolmasky, and J. H. Crosa. 1999. Vibriosis, p. 523-557. In P. Woo and D. Bruno (ed.), Fish diseases and disorders. Viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, vol. 3. Cab International Publishing, Wallingford, England. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Actis, L. A., M. E. Tolmasky, D. H. Farrell, and J. H. Crosa. 1988. Genetic and molecular characterization of essential components of the Vibrio anguillarum plasmid-mediated iron-transport system. J. Biol. Chem. 263:2853-2860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barancin, C. E., J. C. Smoot, R. H. Findlay, and L. A. Actis. 1998. Plasmid-mediated histamine biosynthesis in the bacterial fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Plasmid 39:235-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergendahl, V., U. Linne, and M. A. Marahiel. 2002. Mutational analysis of the C-domain in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:620-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolivar, F. 1978. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. III. Derivatives of plasmid pBR322 carrying unique EcoRI sites for selection of EcoRI generated recombinant DNA molecules. Gene 4:121-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun, V., and H. Killmann. 1999. Bacterial solutions to the iron-supply problem. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:104-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bullen, J. J., and E. Griffiths. 1999. Iron and infection, 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons Ltd., West Sussex, United Kingdom.

- 13.Butterton, J. R., M. H. Choi, P. I. Watnick, P. A. Carroll, and S. B. Calderwood. 2000. Vibrio cholerae VibF is required for vibriobactin synthesis and is a member of the family of nonribosomal peptide synthetases. J. Bacteriol. 182:1731-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chai, S., T. J. Welch, and J. H. Crosa. 1998. Characterization of the interaction between Fur and the iron transport promoter of the virulence plasmid in Vibrio anguillarum. J. Biol. Chem. 273:33841-33847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, Q., L. A. Actis, M. E. Tolmasky, and J. H. Crosa. 1994. Chromosome-mediated 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid is a precursor in the biosynthesis of the plasmid-mediated siderophore anguibactin in Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 176:4226-4234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conti, E., T. Stachelhaus, M. A. Marahiel, and P. Brick. 1997. Structural basis for the activation of phenylalanine in the non-ribosomal biosynthesis of gramicidin S. EMBO J. 16:4174-4183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crosa, J. H. 1989. Genetics and molecular biology of siderophore-mediated iron transport in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 53:517-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crosa, J. H. 1980. A plasmid associated with virulence in the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum specifies an iron-sequestering system. Nature 284:566-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crosa, J. H., L. L. Hodges, and M. H. Schiewe. 1980. Curing of a plasmid is correlated with an attenuation of virulence in the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Infect. Immun. 27:897-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crosa, J. H., and C. T. Walsh. 2002. Genetics and assembly line enzymology of siderophore biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:223-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Lorenzo, M., M. Stork, M. E. Tolmasky, L. A. Actis, D. Farrell, T. J. Welch, L. M. Crosa, A. M. Wertheimer, Q. Chen, P. Salinas, L. Waldbeser, and J. H. Crosa. 2003. Complete sequence of virulence plasmid pJM1 from the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum strain 775. J. Bacteriol. 185:5822-5830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehmann, D. E., C. A. Shaw-Reid, H. C. Losey, and C. T. Walsh. 2000. The EntF and EntE adenylation domains of Escherichia coli enterobactin synthetase: sequestration and selectivity in acyl-AMP transfers to thiolation domain cosubstrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:2509-2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faraldo-Gomez, J. D., and M. S. Sansom. 2003. Acquisition of siderophores in gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:105-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerinot, M. L. 1994. Microbial iron transport. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48:743-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guilvout, I., O. Mercereau-Puijalon, S. Bonnefoy, A. P. Pugsley, and E. Carniel. 1993. High-molecular-weight protein 2 of Yersinia enterocolitica is homologous to AngR of Vibrio anguillarum and belongs to a family of proteins involved in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 175:5488-5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirsch, P. R., and J. E. Beringer. 1984. A physical map of pPH1JI and pJB4JI. Plasmid 12:139-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jalal, M., D. Hossain, D. van der Helm, J. Sanders-Loehr, L. A. Actis, and J. H. Crosa. 1989. Structure of anguibactin, a unique plasmid-related bacterial siderophore from the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111:292-296. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keating, T. A., C. G. Marshall, and C. T. Walsh. 2000. Vibriobactin biosynthesis in Vibrio cholerae: VibH is an amide synthase homologous to nonribosomal peptide synthetase condensation domains. Biochemistry 39:15513-15521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keating, T. A., C. G. Marshall, C. T. Walsh, and A. E. Keating. 2002. The structure of VibH represents nonribosomal peptide synthetase condensation, cyclization and epimerization domains. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:522-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keating, T. A., D. A. Miller, and C. T. Walsh. 2000. Expression, purification, and characterization of HMWP2, a 229 kDa, six domain protein subunit of Yersiniabactin synthetase. Biochemistry 39:4729-4739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keating, T. A., and C. T. Walsh. 1999. Initiation, elongation, and termination strategies in polyketide and polypeptide antibiotic biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3:598-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koster, W. L., L. A. Actis, L. S. Waldbeser, M. E. Tolmasky, and J. H. Crosa. 1991. Molecular characterization of the iron transport system mediated by plasmid pJM1 in Vibrio anguillarum 775. J. Biol. Chem. 266:23829-23833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marahiel, M. A., T. Stachelhaus, and H. D. Mootz. 1997. Modular peptide synthetases involved in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Chem. Rev. 97:2651-2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall, C. G., N. J. Hillson, and C. T. Walsh. 2002. Catalytic mapping of the vibriobactin biosynthetic enzyme VibF. Biochemistry 41:244-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller, D. A., L. Luo, N. Hillson, T. A. Keating, and C. T. Walsh. 2002. Yersiniabactin synthetase: a four-protein assembly line producing the nonribosomal peptide/polyketide hybrid siderophore of Yersinia pestis. Chem. Biol. 9:333-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mootz, H. D., D. Schwarzer, and M. A. Marahiel. 2002. Ways of assembling complex natural products on modular nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chem. Biochem. 3:490-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogura, T., and A. J. Wilkinson. 2001. AAA+ superfamily ATPases: common structure—diverse function. Genes Cells 6:575-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quadri, L. E., T. A. Keating, H. M. Patel, and C. T. Walsh. 1999. Assembly of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa nonribosomal peptide siderophore pyochelin: In vitro reconstitution of aryl-4, 2-bisthiazoline synthetase activity from PchD, PchE, and PchF. Biochemistry 38:14941-14954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ratledge, C., and L. G. Dover. 2000. Iron metabolism in pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:881-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roche, E. D., and C. T. Walsh. 2003. Dissection of the EntF condensation domain boundary and active site residues in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Biochemistry 42:1334-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 44.Schlumbohm, W., T. Stein, C. Ullrich, J. Vater, M. Krause, M. A. Marahiel, V. Kruft, and B. Wittmann-Liebold. 1991. An active serine is involved in covalent substrate amino acid binding at each reaction center of gramicidin S synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 266:23135-23141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stachelhaus, T., A. Huser, and M. A. Marahiel. 1996. Biochemical characterization of peptidyl carrier protein (PCP), the thiolation domain of multifunctional peptide synthetases. Chem. Biol. 3:913-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stachelhaus, T., H. D. Mootz, V. Bergendahl, and M. A. Marahiel. 1998. Peptide bond formation in nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis. Catalytic role of the condensation domain. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22773-22781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stein, T., J. Vater, V. Kruft, A. Otto, B. Wittmann-Liebold, P. Franke, M. Panico, R. McDowell, and H. R. Morris. 1996. The multiple carrier model of nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis at modular multienzymatic templates. J. Biol. Chem. 271:15428-15435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tolmasky, M. E., L. A. Actis, and J. H. Crosa. 1988. Genetic analysis of the iron uptake region of the Vibrio anguillarum plasmid pJM1: molecular cloning of genetic determinants encoding a novel transactivator of siderophore biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 170:1913-1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tolmasky, M. E., L. A. Actis, and J. H. Crosa. 1995. A histidine decarboxylase gene encoded by the Vibrio anguillarum plasmid pJM1 is essential for virulence: histamine is a precursor in the biosynthesis of anguibactin. Mol. Microbiol. 15:87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tolmasky, M. E., and J. H. Crosa. 1995. Iron transport genes of the pJM1-mediated iron uptake system of Vibrio anguillarum are included in a transposonlike structure. Plasmid 33:180-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Dohren, H., R. Dieckmann, and M. Pavela-Vrancic. 1999. The nonribosomal code. Chem. Biol. 6:R273-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Dohren, H., U. Keller, J. Vater, and R. Zocher. 1997. Multifunctional peptide synthetases. Chem. Rev. 97:2675-2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walter, M. A., S. A. Potter, and J. H. Crosa. 1983. Iron uptake system mediated by Vibrio anguillarum plasmid pJM1. J. Bacteriol. 156:880-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weber, T., R. Baumgartner, C. Renner, M. A. Marahiel, and T. A. Holak. 2000. Solution structure of PCP, a prototype for the peptidyl carrier domains of modular peptide synthetases. Structure Fold Des. 8:407-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Welch, T. J., S. Chai, and J. H. Crosa. 2000. The overlapping angB and angG genes are encoded within the trans-acting factor region of the virulence plasmid in Vibrio anguillarum: essential role in siderophore biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 182:6762-6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wertheimer, A. M., M. E. Tolmasky, L. A. Actis, and J. H. Crosa. 1994. Structural and functional analyses of mutant Fur proteins with impaired regulatory function. J. Bacteriol. 176:5116-5122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wertheimer, A. M., W. Verweij, Q. Chen, L. M. Crosa, M. Nagasawa, M. E. Tolmasky, L. A. Actis, and J. H. Crosa. 1999. Characterization of the angR gene of Vibrio anguillarum: essential role in virulence. Infect. Immun. 67:6496-6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolf, M. K., and J. H. Crosa. 1986. Evidence for the role of a siderophore in promoting Vibrio anguillarum infections. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:2949-2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]