Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, encodes an RpoS ortholog (RpoSBb) that controls the temperature-inducible differential expression of at least some of the spirochete's lipoprotein genes, including ospC and dbpBA. To begin to dissect the determinants of RpoSBb recognition of, and selectivity for, its dependent promoters, we linked a green fluorescent protein reporter to the promoter regions of several B. burgdorferi genes with well-characterized expression patterns. Consistent with the expression patterns of the native genes/proteins in B. burgdorferi strain 297, we found that expression of the ospC, dbpBA, and ospF reporters in the spirochete was RpoSBb dependent, while the ospE and flaB reporters were RpoSBb independent. To compare promoter recognition by RpoSBb with that of the prototype RpoS (RpoSEc), we also introduced our panel of constructs into Escherichia coli. In this surrogate, maximal expression from the ospC, dbpBA, and ospF promoters clearly required RpoS, although in the absence of RpoSEc the ospF promoter was weakly recognized by another E. coli sigma factor. Furthermore, RpoSBb under the control of an inducible promoter was able to complement an E. coli rpoS mutant, although RpoSEc and RpoSBb each initiated greater activity from their own dependent promoters than they did from those of the heterologous sigma factor. Genetic analysis of the ospC promoter demonstrated that (i) the T(−14) in the presumptive −10 region plays an important role in sigma factor recognition in both organisms but is not as critical for transcriptional initiation by RpoSBb as it is for RpoSEc; (ii) the nucleotide at the −15 position determines RpoS or σ70 selectivity in E. coli but does not serve the same function in B. burgdorferi; and (iii) the 110-bp region upstream of the core promoter is not required for RpoSEc- or RpoSBb-dependent activity in E. coli but is required for maximal expression from this promoter in B. burgdorferi. Taken together, the results of our studies suggest that the B. burgdorferi and E. coli RpoS proteins are able to catalyze transcription from RpoS-dependent promoters of either organism, but at least some of the nucleotide elements involved in transcriptional initiation and sigma factor selection in B. burgdorferi play a different role than has been described for E. coli.

All microorganisms must sense and respond to changes in environmental stimuli in order to survive. Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, encounters the osmotic, thermal, nutritional, and immunological milieus of two hosts, a tick vector of the Ixodes genus and a mammalian host, usually a small rodent (46, 78). While there is now a substantial body of evidence that the Lyme disease spirochete's transition between these two host environments is coincident with dramatic changes in the bacterium's proteome (reviewed in references 6, 40, 64, 71, and 74), the contribution of most of these gene products to spirochete physiology and/or virulence is poorly understood. Consequently, characterizing differentially expressed B. burgdorferi proteins, as well as dissecting the networks regulating their expression, has moved to the center stage of Lyme disease pathogenesis research. Norgard and colleagues (39, 90) recently described one such network in which the response regulator, Rrp2, acts through the alternate sigma factor RpoN to control rpoS expression. Under in vitro conditions that ostensibly mimic those that occur during tick feeding, B. burgdorferi RpoS (RpoSBb) mediates the temperature-dependent differential expression of the genes for at least two B. burgdorferi proteins, outer surface protein C (OspC) and decorin-binding protein A (DbpA) (39).

In Escherichia coli, RpoS (RpoSEc) accumulates during the stationary phase of growth or under a variety of environmental stresses, including starvation, high osmolarity, temperature shift, and acidic pH (35, 36), and is known to regulate the expression of at least 100 genes (38, 41, 52). Several parameters contribute to the specificity of RpoSEc for its dependent promoters, including reduced negative supercoiling, high osmolarity, modulation by trans-acting factors, the presence or sequence of the −35 region, and perhaps most importantly, the sequence of the “extended” −10 region (reviewed in reference 37). Although most of the B. burgdorferi promoters described to date (11, 19, 26, 27, 29, 33, 55, 56, 65, 76, 77, 88) appear to have the −35 and −10 elements recognized by members of the σ70 family, which includes both RpoS and the housekeeping sigma factor, σ70 (53), little is known about the molecular parameters that directly influence sigma factor selectivity or transcriptional initiation of B. burgdorferi genes. Defining the features that determine sigma factor specificity for select promoters may assist in our understanding of the role(s) of RpoSBb-dependent and -independent gene expression in the physiology and virulence of B. burgdorferi. Such studies also have the potential to expand our understanding of promoter recognition by sigma factors in general.

The use of reporters in evaluating borrelial differential gene expression has contributed significantly to characterizing B. burgdorferi promoters. Previously, the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene was used as a transient reporter in B. burgdorferi to study the net changes in transcription of ospA and ospC within a population of spirochetes (5, 76, 77). More recently, we developed a stable shuttle vector to introduce the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (gfp) under the control of the flaB promoter (PflaB) into B. burgdorferi (20). Using flow cytometry, we demonstrated the utility of this transcriptional reporter for studying gene expression by individual spirochetes within a population (20). Subsequently, Carroll et al. (15) introduced gfp under the control of the promoters for ospA (PospA) and ospC (PospC) into B. burgdorferi and found that these reporters accurately reflected the expected in vitro expression patterns of these genes in response to changes in temperature and pH. In this report, we have linked fluorescent transcriptional reporters to the promoters of several well-defined temperature-inducible B. burgdorferi lipoprotein genes to explore RpoSBb-dependent transcription by comparing the similarities and differences of RpoS recognition and selectivity in both B. burgdorferi and an E. coli surrogate. Our results suggest that, despite the ability of RpoS polypeptides from both E. coli and B. burgdorferi to catalyze transcription from ostensibly similar promoters, at least some of the nucleotide elements of RpoSBb-dependent promoters play different roles in sigma factor selectivity and transcriptional initiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

B. burgdorferi strain 297 clone c155 (20) and an isogenic strain 297 rpoS mutant, c174 (see below), were routinely cultivated in modified Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK-H complete; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) medium. Spirochetes were passaged no more than three times before experimental manipulations were performed. The plasmid contents of the B. burgdorferi strains used in this study were monitored by PCR as described previously (20). The protocol used for competent cell preparation and electroporation of B. burgdorferi strain 297 c155 or c174 has been previously described (20, 69). Transformations were carried out by using approximately 10 μg of plasmid DNA per reaction, and selection of transformants was done in the presence of 400 μg of kanamycin ml−1. All B. burgdorferi transformants were maintained in the presence of kanamycin. For temperature shift experiments, clones were grown to 1 × 107 to 5 × 107 cells/ml at 23°C and then inoculated at a density of 104 cells/ml and grown to 0.5 × 108 to 1 × 108 cells/ml at 37°C.

Routine cloning and plasmid propagation were performed with E. coli strain Top10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). ZK126 (W3110 ΔlacU169 tna-2) (18) and ZK1000 (ZK126 rpoS::kan) (10) were kindly provided by R. Kolter (Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.); MC4100 [F− araD139 Δ(argF-lacZYA)U169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR] (75) and LM5005 [MC4100 csi-5::lacZ (osmY::lacZ) rpoS379::Tn10] (30) were generously provided by H. Shuman (Columbia University, New York, N.Y). All strains were maintained in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) with the appropriate antibiotic, except when zeocin (50 μg−1 ml; Invitrogen) was required, in which case SOB medium (2% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.05% NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2) was used. Solid-phase selection was performed on LB agar plates (LB with 1.5% agar) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic or low-salt LB agar plates (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, 1.5% agar) supplemented with zeocin.

Construction of c174.

To generate a B. burgdorferi rpoS mutant in the clonal c155 background, a 3-kb region of total genomic AH200 DNA (39) (kindly provided by M. Norgard, University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, Tex.) including the rpoS::ermC cassette was PCR amplified using the upsRpoS-5′ and dwnRpoS-3′ primers (Table 1) and TaKaRa ExTaq (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) high-fidelity polymerase. The amplicon was purified, concentrated by ethanol precipitation, and used to electrotransform competent B. burgdorferi 297-c155 (20, 69). Electrotransformation reactions were recovered in 4 ml of BSK-H at 33°C overnight and then plated in two 96-well plates, each in a total 40 ml of BSK-H containing 0.06 μg of erythromycin ml−1. Plates were incubated at 33°C under 5% CO2 for 10 to 14 days.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Use |

|---|---|---|

| BbPflaB-5′ (SphI) | GCGCATGCTGTCTGTCGCCTCTTGTGG | Bb PflaB |

| BbPflaB-3′ (SalI) | GCGTCGACATATCATTCCTCCATGATAAAATTT | Bb PflaB |

| BbPdbpBA-5′ (SphI) | GCGCATGCCTATATTTGCATAAAACAAATTCAC | Bb PdbpBA |

| BbPdbpBA-3′ (SalI) | GCGTCGACCATTTTTTCCTCCTTCTATTAAATTTAG | Bb PdbpBA |

| BbPospC-5′ (SphI) | GCGCATGCGCCTGAGTATTCATTATATAAGTC | Bb PospC |

| BbPospC-3′ (SalI) | GCGTCGACTAATTTGTGCCTCCTTTTTATTTATG | Bb PospC |

| BbPospCtrunc-F (SphI) | GAGCATGCTAAAAAATTGAAAAACAAAATTGT | Bb PospCtrunc |

| BbPospE/F-5′ (SphI) | GGCTTCTCATTGCATGCAAAATTTGG | Bb PospE, PospF |

| ospE spec-3′ | CTTTATTGTTTTCTTCAACACCCT | Bb ospE internal |

| ospF spec-3′ | CATCTATAACTTTGTTTGCCAATTCATTGC | Bb ospF internal |

| PospE prom-3′ (BamHI) | GGGATCCAAGTTACTCCTAAAGTACTAATAGTAC | Bb PospE |

| PospF prom-3′ (BamHI) | GGGATCCAAGTTACTCCTAAAATCCTTAAGTCTA | Bb PospF |

| PosmY-5′ (SphI) | GCGCATGCCTGGCACAGGAACGTTATCCGG | Ec PosmY |

| PosmY-3′ (EcoRI) | CGAATTCCGATTTATTCCTGTATGTTTGCTC | Ec PosmY |

| GFPmut1-5′-R seq | ATCACCTTCACCCTCTCCACTGAC | Sequencing |

| PospCmutT→A-F | CAAAATTGTTGGACAAATAATTCATAAAT | PospCTA |

| PospCmutT→A-R | ATTTATGAATTATTTGTCCAACAATTTTG | PospCTA |

| PospCmutC→G-F | CAAAATTGTTGGAGTAATAATTCATAAAT | PospCCG |

| PospCmutC→G-R | ATTTATGAATTATTACTCCAACAATTTTG | PospCCG |

| BBB18-F | AGAAGCAGGACTTCCACTTAG | Upstream ospC |

| BBB19-R | ACTTTCTGCCACAACAGGG | ospC internal |

| RpoS-5′ (SacI) | GTGAGCTCTAAAAACTTAATCACAATATTCAAGA | pBAD-rpoSBb |

| RpoS-3′ (Xbal) | ACTCTAGATTAATTTATTTCTTCTTTTAATTTTTTA | pBAD-rpoSBb |

| UpsRpoS-5′ | AACTTATCTTGGAGGAAATTGATG | Constructing CE174 |

| DwnRpoS-3′ | CTTGCAAATGCCTGAGTTATTGCA | Constructing CE174 |

Restriction sites are underlined; nucleotides altered to introduce desired mutations are shown in bold.

Fluorescent reporter constructs.

Table 1 lists all primers used for this study. Upstream regions from the genes of interest were amplified by PCR and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen). Primer locations were chosen to encompass each gene's promoter as identified by primer extension (26, 29, 33, 55). The upstream regions of the flaB (PflaB) and dbpA (PdbpBA) genes were amplified by PCR from B. burgdorferi strain B31-MI genomic DNA, using specific primers based on the published sequences (16, 23). The 245-bp PospC was amplified from B. burgdorferi strain 297 DNA, using primers based on the B31-MI sequence (23). A truncation of PospC (PospCtrunc) also was PCR amplified from B. burgdorferi strain 297 DNA, using the BbPospCtrunc-F and BbPospC-3′ primers. To clone the upstream regions of the ospE (PospE) and ospF (PospF) genes, which are located on largely redundant 32-kb circular plasmids (13), PCR amplification from strain 297 genomic DNA was first performed using a forward conserved primer (BbPospE/F-5′) located 319 bp upstream of the translational start site and an internal reverse primer specific for each locus (ospEspec-3′ and ospFspec-3′), and subsequently cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO. PospE and PospF were then amplified from purified plasmid DNAs, using the BbPospE/F-5′ and either the PospE prom-3′ primer or the PospF prom-3′ primer, respectively. The promoter of the RpoSEc-dependent osmY gene (PosmY) (47, 92) was amplified from E. coli strain LM5005 DNA by using the PosmY-5′ and PosmY-3′ primers.

Shuttle vectors containing a gfp allele (60, 61) under the control of the various B. burgdorferi promoters (PBb) were constructed as follows. The ClaI-BglII fragment of pWM1015 (20), containing four upstream terminators, a ribosomal binding site, and a consensus Campylobacter promoter (Pcampy) cloned directly upstream of a gfp gene (60), was subcloned into the ClaI and BamHI sites of pBluescript II SK(+) (Ampr; Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), creating pBS(gfp)-Pcampy. Each of the PBb described above was excised from its respective pCR2.1-TOPO construct by using SphI and EcoRI and subcloned into pBS(gfp)-Pcampy upstream of the ribosomal binding site within the gfp cassette, replacing the consensus Pcampy. For most of the promoters, the entire PBb-gfp cassette was then cloned into the SacI and XhoI sites of the B. burgdorferi shuttle vector, pCE320 (20). The gfp gene under the control of PosmY (92) was cloned into pCE300, the pCE320 precursor lacking the B. burgdorferi replication origin (20), using the same scheme as described above. To create a promoterless gfp cassette to serve as a negative control, pBS(gfp)-Pcampy was digested with SphI and EcoRI, treated with mung bean nuclease (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and religated. The promoterless gfp cassette was then subcloned into pCE320, as described above. For complementation with either pBAD-rpoSBb or pBAD-rpoSEc (see below), the PBb-gfp cassettes, as well as PosmY-gfp, were digested out of the pBS(gfp) intermediate by using ClaI and XbaI and cloned into the corresponding sites of the low-copy-number vector, pACYC184 (New England Biolabs). Promoter sequences for all constructs were confirmed by sequencing with the GFPmut1-5′-R primer (Table 1).

Site-directed mutagenesis of the putative RpoS-binding sites of PospC.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the predicted RpoS-binding site of PospC was performed using the overlapping forward and reverse primers, PospCmutT→A (for PospCTA) or PospCmutC→G (for PospCCG) (Table 1). Briefly, two overlapping fragments were amplified by PCR using the BBB18F primer or the BBB19R primer and the appropriate downstream or upstream mutation primer, respectively. The products were purified using the CONCERT PCR rapid purification kit as instructed by the manufacturer. The two purified products were diluted to 100 ng μl−1, and 1 μl of each product was subsequently used as a template in a second PCR, which was amplified without primers for four cycles of 92°C for 15s, 60°C for 15s, and 72°C for 2 min before the flanking BBB18F and BBB19R primers were added, and the PCR was continued for 25 more cycles. This product was again gel purified, and the PospC was amplified using the PospC-5′ and PospC-3′ primers and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO. Each mutated PospC was cloned into pBS(gfp)-Pcampy and pCE320 as described above. The presence of the mutation was confirmed by sequencing with the internal gfp primer, GFPmut1-5′-R.

Testing the RpoS dependence of B. burgdorferi promoters in an E. coli surrogate.

Cultures of either ZK126 (wild-type rpoS) or ZK1000 (rpoS::kan) containing the various pCE320(gfp)-PBb vectors were grown overnight at 25°C, diluted to 0.01 A600 units in SOB supplemented with 50 μg of zeocin ml−1, and then incubated at 37°C. The RpoS dependence of PospCtrunc, PospCTA, and PospCCG cloned into pBS(gfp) was compared to that of the full-length PospC in the same vector in the MC4100 (wild-type rpoS) and the LM5005 (rpoS::kan) backgrounds in SOB supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin ml−1. For each assay, the optical density at 600 nm was determined at hourly intervals; beginning 2 h after inoculation, 0.5 ml of sample was fixed with paraformaldehyde and analyzed by flow cytometry, as described below.

Flow cytometry.

Samples containing ≥107 cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Palo Alto, Calif.) with a 15-mW 488-nm air-cooled argon laser and an ≈635-nm red diode laser as previously described (20). Staining of B. burgdorferi cells with the nucleic acid stain SYTO59 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Ore.), was done as described previously (20), with the addition of STE (10 mM Tris · Cl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl) washes prior to and after staining. Cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in FA buffer (final concentration, 0.8%; Difco). For each B. burgdorferi sample, data were collected for 25,000 to 50,000 SYTO59+ events. Because of the uniformity of the E. coli cultures, SYTO59+ staining was not necessary; samples were fixed directly, and data were collected for 50,000 events. Flow cytometry data were analyzed by using either CELLQUEST version 3.3 (Becton Dickinson) or WinMDI version 2.8 (http://facs.scripps.edu).

Construction of the RpoSBb-complementing plasmid.

A plasmid containing E. coli rpoS under the control of the araBAD promoter (pBAD-rpoSEc) (85) was kindly provided by F. C. Fang, University of Washington, Seattle, Wash. The B. burgdorferi rpoS gene was amplified from B. burgdorferi strain 297 DNA using the RpoS-5′ (SacI) and RpoS-3′ (XbaI) primers (Table 1). The resulting product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO and then directionally subcloned into pBAD18 (28) by using SacI and XbaI, generating pBAD-rpoSBb.

Complementation of an E. coli rpoS mutant.

Cultures of LM5005 transformed with pBAD-rpoSEc, pBAD-rpoSBb, or pBAD were started as for the growth curves described above and then split after 3 h, and one aliquot was induced with 0.2% arabinose. After 1 h, aliquots of both uninduced and induced cultures were removed, and β-galactosidase activity was measured spectrophotometrically using o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside as a substrate (59).

To test the ability of pBAD-rpoSBb or pBAD-rpoSEc to restore promoter activity to B. burgdorferi RpoS-dependent promoters, MC4100 and LM5005 were transformed with both a pACYC184(gfp)-PBb vector and either pBAD-rpoSEc, pBAD-rpoSBb, or the pBAD control plasmid. Double transformants were selected on agar plates containing both 100 μg of ampicillin ml−1 and 25 μg of chloramphenicol ml−1. Cultures grown at 25°C were inoculated at a density of 0.01 optical density units per ml into LB supplemented with both antibiotics. Cultures were induced with 0.06% arabinose after 6 h of growth at 37°C, and samples were collected for flow cytometry and β-galactosidase assays 2 h postinduction.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis.

B. burgdorferi whole-cell lysates of 297-c155 and 297-c174 were prepared from spirochetes cultivated in BSK-H to a density of 5 × 107 cells ml−1 at either 23 or 37°C following a temperature shift from 23°C. Cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 8,500 × g, and the resulting pellets were washed twice with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline. Equivalent amounts of cells were resuspended, boiled in reducing Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), and separated through 2.4% stacking and 12.5% separating polyacrylamide minigels. Separated proteins were visualized by silver staining according to the method described by Morrissey (62). For immunoblotting, proteins were transferred to a nylon-supported nitrocellulose membrane (Micron Separations, Inc., Westborough, Mass.) and incubated with 1:1,000 to 1:5,000 dilutions of previously described rat polyclonal antisera directed against DbpA (29), OspE (1), and OspF (3). Blots were then probed with a 1:45,000 to 1:60,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antirat (or antimouse) antibody (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) and developed using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce, Rockford, Ill). B. burgdorferi lysates were assessed for loading and electrotransfer uniformity by immunoblotting using a monoclonal antibody (1H6-33) directed against FlaB (1).

Nucleotide sequencing and computer analyses.

Nucleotide sequencing was performed by the UCHC Molecular Core Facility, using an Applied Biosystems Inc. model 373A automated DNA sequencer and PRISM ready reaction DyeDeoxy Terminator cycle sequencing kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.). Routine sequence analysis and multiple sequence alignments were performed by using MacVector version 7.1 software (Accelrys Bioinformatics). Open reading frames were analyzed for potential conserved domains by using ScanProsite (25).

Statistical analyses.

To determine the statistical significance of observed differences, matching data points (n ≥ 3) were compared within GraphPad Prism v3.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.) by using an unpaired t test with two-tailed P values and a 95% confidence interval. Asterisks indicate a level of significance where P values are ≤0.01. Error bars in figures represent the standard errors of the means.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of PospC from B. burgdorferi strain 297 was submitted to GenBank under accession no. AY370509.

RESULTS

Use of fluorescent reporters to monitor temperature-dependent gene expression in both wild-type and rpoS mutant clones of B. burgdorferi strain 297.

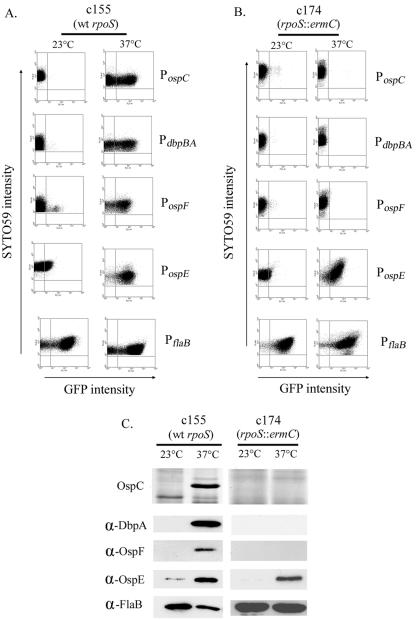

In a previous study (20), we used gfp under the control of the constitutive PflaB (26) to demonstrate the feasibility of using fluorescent reporters for studying gene expression in B. burgdorferi. To extend these techniques to the study of differential gene expression, we constructed a series of pCE320-based vectors (20) containing gfp under the transcriptional control of PospC, PdbpBA, PospE, and PospF. These promoters were chosen, in part, because the transcriptional start site of each had been previously identified by primer extension (29, 33, 55) and each had a well-characterized expression pattern (1, 3, 5, 6, 33, 72, 79, 89). Isolates of the virulent B. burgdorferi strain 297 clone c155 (20) transformed with each of the fluorescent constructs, as well as pCE320(gfp)-PflaB, were cultivated at 23 and 37°C, the temperatures used in vitro to mimic the arthropod and mammalian host environments, respectively. The results for samples analyzed by flow cytometry are shown in Fig. 1A and Table 2. Consistent with previously published protein and/or RNA data (1, 3, 5, 6, 33, 72, 79, 89), the activities of the temperature-inducible promoters were markedly higher after temperature shift, while the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of spirochetes containing PflaB-gfp increased only modestly (Table 2). The combination of GFP and flow cytometry has been employed previously to demonstrate transcriptional heterogeneity in E. coli populations (54). Thus, we also noted that with each promoter at 37°C, there were spirochetes (one SYTO59+ event = one spirochete) that did not express appreciable levels of GFP, suggesting a marked transcriptional variability among individuals within a population. Our results are consistent with published reports demonstrating considerable variability in expression of the corresponding proteins within a population of spirochetes (22, 32, 33, 63). When these same constructs were introduced into the rpoS mutant, 297-c174, we found that PospC, PdbpBA, and PospF fluorescence was low at 23°C, but unlike in the wild-type clone, showed no significant increase following a temperature shift to 37°C, demonstrating their RpoS dependence (Fig. 1B and Table 2). We also found that similar to that of PflaB, the expression of PospE was RpoSBb independent. These results were consistent with the protein expression profiles of the parent and rpoS mutant (Fig. 1C), further validating the use of fluorescent reporters for studying differential gene expression in B. burgdorferi. In a parallel study (12), we found that complementing 297-c174 with plasmid-borne RpoS restored wild-type levels of OspC, DbpBA, and OspF expression.

FIG. 1.

GFP reporters of ospC, dbpA, ospF, and ospE transcription reflect the temperature dependence (A) and RpoS dependence (B) of the native B. burgdorferi genes. Flow cytometry was performed by using samples taken from cultures grown at either 23 or 37°C. The y axis indicates the level of the SYTO59 nucleic acid stain used to selectively gate on spirochetes. The x axis represents the intensity of GFP fluorescence (transcriptional strength) of the SYTO59+ events (spirochetes). (C) Results of the reporter studies were confirmed by either silver staining or immunoblot analysis of cell lysates from B. burgdorferi strain 297-c155 or 297-c174 (rpoS::ermC) cultivated at 23 and 37°C following temperature shift. Lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and either silver stained or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblot analysis using antisera directed against DbpA, OspF, OspE, and FlaB.

TABLE 2.

Data from Fig. 1A and B

| Strain (genotype) | Promoter | MFI (%a)

|

Fold increase in MFI (37°C over 23°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23°C | 37°C | |||

| 297-c155 (wild-type rpoS) | None | 1.7 (0.05) | 1.8 (0.22) | 1.1 |

| PospC | 1.5 (0.03) | 50.3 (52.2) | 34 | |

| PdbpBA | 1.9 (0.23) | 63.7 (56.6) | 34 | |

| PospF | 2.5 (3.3) | 29.7 (64.6) | 12 | |

| PospE | 7 (37.2) | 75.5 (87.7) | 11 | |

| PflaB | 166.9 (78.7) | 223 (83.5) | 1.3 | |

| 297-c174 | None | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.49) | 0.9 |

| (rpoS::ermC) | PospC | 2.0 (0.89) | 1.7 (0.04) | 0.9 |

| PdbpBA | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.02) | 1 | |

| PospF | 1.8 (0.64) | 1.9 (0.22) | 1.1 | |

| PospE | 3.7 (7.0) | 33.0 (88.3) | 8.9 | |

| PflaB | 208.7 (94.2) | 240 (95.2) | 1.2 | |

Percentages are given as 100 × (number of events with a GFP fluorescence intensity greater than 8)/(total number of SYTO59+ events).

RpoS dependence of B. burgdorferi genes in an E. coli surrogate.

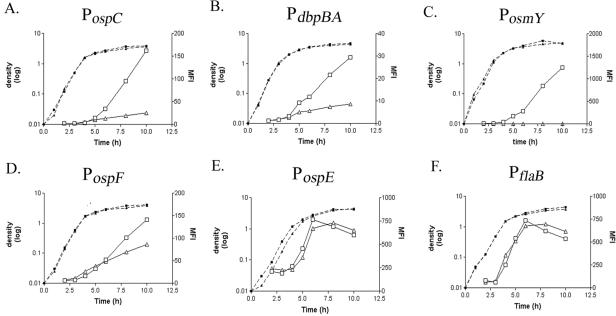

Consistent with other reports (39, 68, 91), the above-described results suggested that the temperature-dependent differential expression of B. burgdorferi genes occurs through both RpoS-dependent and -independent pathways. Nothing is known, however, about the molecular parameters that influence specificity for these genes in B. burgdorferi. Because the determinants of sigma factor selectivity have been best characterized for E. coli, we thought it would be of considerable interest to examine the activities of our panel of reporter constructs in an E. coli surrogate. In an rpoS mutant strain of E. coli, we found that transcription from PospC and PdbpBA, as measured by fluorescence intensity, was markedly reduced from that of the wild-type parent (Fig. 2A and B). Additionally, in the wild-type E. coli parent, the highest expression levels from these promoters were not reached until stationary phase, when RpoSEc-dependent expression is known to be maximal (36, 41). The behavior of these two borrelial promoters was consistent with the expression pattern exhibited by the promoter for the RpoS-dependent E. coli osmY gene (70, 92) (PosmY) (Fig. 2C). As with PospC or PdbpBA, we observed a low level of fluorescence from PosmY in the rpoS mutant. In the presence of RpoSEc, however, the maximal level of expression was ≥10 times that from either of the two RpoSBb-dependent promoters, suggesting that RpoSEc was able to more readily initiate transcription from the E. coli promoter. In contrast to the case with PospC and PdbpBA, the RpoS dependence of PospF was not as clear in the E. coli surrogate. Although this promoter was RpoS dependent in B. burgdorferi (Fig. 1), in the E. coli rpoS mutant, PospF was still transcribed to a level nearly 60% of the wild-type level (Fig. 2D), presumably reflecting the ability of another E. coli sigma factor to recognize this promoter. Unlike the RpoS-dependent promoters, the RpoS-independent PospE (Fig. 2E) and PflaB (Fig. 2F) were initially expressed at high levels, with expression continuing to increase during logarithmic growth and peaking at the onset of stationary phase in both the wild-type and rpoS mutant strains of E. coli. Similar phase-dependent increases in expression have also been noted for many RpoS-independent E. coli genes (70). Taken together, our results suggested that E. coli could discriminate between RpoS-dependent and -independent B. burgdorferi promoters, though not with the same degree of specificity as observed in the spirochete.

FIG. 2.

An E. coli surrogate can discriminate between RpoS-dependent and -independent B. burgdorferi genes. The activities of PospC (A), PdbpBA (B), the E. coli promoter, PosmY (C), PospF (D), PospE (E), and PflaB (F) in E. coli strains with either a wild-type rpoS gene (ZK126; boxes) or an insertionally mutated rpoS gene (ZK1000; triangles) were analyzed by flow cytometry. The cell density (dashed lines) and the MFIs (solid lines) were plotted against time on the representative graphs.

Complementation of an E. coli rpoS mutant with RpoSBb.

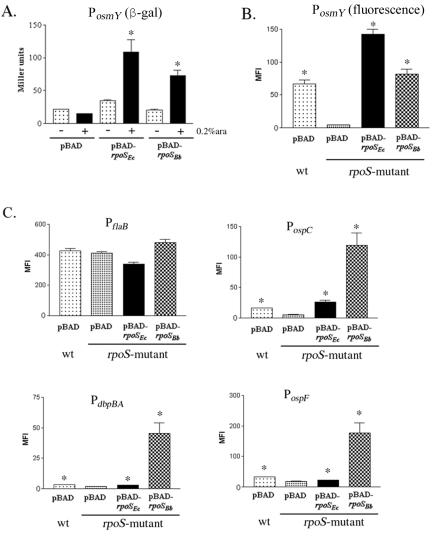

The findings that RpoSEc could initiate transcription from RpoSBb-dependent promoters, but not with the same specificity or to the same levels of activity as for its cognate dependent promoter(s), suggested to us that there are both conserved and species-specific elements determining RpoS selectivity and transcriptional initiation in the RpoS-dependent promoter sequences from B. burgdorferi and E. coli. To establish a model system for directly comparing the abilities of RpoSEc and RpoSBb to initiate transcription from RpoS-dependent promoters of either organism, we first needed to confirm that the B. burgdorferi RpoSBb subunit functioned within E. coli. For these studies, we took advantage of an E. coli rpoS mutant previously utilized to identify RpoS orthologs in both Legionella pneumophila (30) and Coxiella burnetti (73). This mutant, LM5005, contains a chromosomal lacZ reporter under the control of the RpoSEc-dependent PosmY (92); complementation of the E. coli rpoS gene with an RpoS homolog results in an increase in β-galactosidase activity (30). For these experiments, plasmids containing either RpoSBb (pBAD-rpoSBb) or RpoSEc (pBAD-rpoSEc) under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter were introduced into LM5005. To assess RpoSBb and RpoSEc activity, cells grown with or without arabinose were assayed for β-galactosidase activity 1 h postinduction. As shown in Fig. 3A, expression of either RpoS protein complemented the rpoS mutation, while the vector alone had no effect on β-galactosidase levels. As a key control for our plasmid-based reporter studies (see below), we wanted to establish that RpoSBb also was able to promote activity from a plasmid-borne gfp gene under the control of PosmY. For this assay, the PosmY-gfp fusion was first cloned into the low-copy-number pACYC184 vector, which is compatible with the pBR322 origin of the pBAD vector. Using this construct, we found that after arabinose induction, the level of gfp expression from the plasmid-encoded PosmY in LM5005 in the presence of RpoSBb was much greater than in the mutant containing pBAD alone (Fig. 3B). As would be expected, we also found that the expression levels from the lower-copy-number pACYC184 platform were significantly less than those observed in a previous experiment using the much higher-copy-number ColE1-based plasmid (Fig. 2C). We also noted that the activity levels from both the chromosomally and plasmid-encoded PosmY were higher in the presence of RpoSEc than they were in the mutant complemented with RpoSBb (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG. 3.

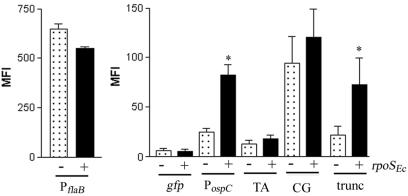

RpoSBb can transcribe both RpoSEc- and RpoSBb-dependent promoters in an E. coli surrogate. (A) Cell lysates from the rpoS mutant LM5005 transformed with pBAD, pBAD-rpoSBb, or pBAD-rpoSEc were prepared from either uninduced (−) cultures or induced (+) cultures 1 h following the addition of 0.2% arabinose (ara) and assayed for β-galactosidase activity (expressed as Miller units) from the chromosomal PosmY-lacZ fusion. (B) The parent strain, MC4100 (wild type), with pBAD or LM5005 containing the pBAD, pBAD-rpoSEc, or pBAD-rpoSBb vector was transformed with pACYC184(gfp)-PosmY or (C) with pACYC184(gfp)-PospC, -PdbpBA, -PospF, or -PflaB. Samples for analysis were collected 2 h following induction with 0.06% arabinose, and promoter activity as a function of gfp expression was measured by flow cytometry. Asterisks indicate significant levels of β-galactosidase activity (A) or fluorescence (B and C) in the presence of either RpoSBb or RpoSEc relative to the induced mutant carrying pBAD alone (P ≤ 0.01). Each graph represents the average for three trials.

The above-described results suggested that RpoSBb was capable of forming a functional chimeric polymerase with the E. coli core RNA polymerase (RNAP) subunits. To directly compare the transcriptional activities of RpoSBb and RpoSEc in identical backgrounds, the various borrelial promoter-gfp constructs in the compatible low-copy-number pACYC184 vector were transformed into both LM5005 containing pBAD, pBAD-rpoSEc, or pBAD-rpoSBb and the parent strain, MC4100, containing pBAD. As expected, the induction of RpoSBb and RpoSEc resulted in little change in the levels of promoter activity of PflaB (Fig. 3C), while no fluorescence was observed from the construct containing the promoterless gfp (not shown). In the presence of RpoSBb, however, the activity of each of the B. burgdorferi RpoS-dependent promoters (PospC, PdbpBA, and PospF) was induced 10- to 20-fold over that of the rpoS mutant containing the pBAD vector alone and 5- to 10-fold over either the wild-type strain containing pBAD or LM5005 containing pBAD-rpoSEc (Fig. 3C). These results, in combination with those from Fig. 2, indicated that RpoSEc and RpoSBb each preferentially recognize their cognate promoters and further supported the notion that there are different promoter elements or motifs (possibly including those at which a trans-acting factor other than RpoS could bind) that determine effective sigma factor selection and transcriptional initiation in the respective organisms.

Mapping the putative RpoS recognition motif of the ospC promoter.

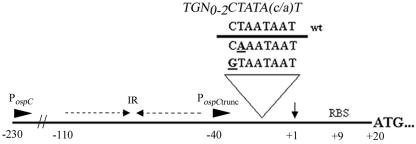

In a previous study by Marconi et al. (55), primer extension from the ospC gene of the Pko isolate of Borrelia afzelii identified a strong promoter (P1) containing both a consensus −35 and −10 box located within 60 nucleotides of the translational start site (diagrammatically presented in Fig. 4). An alignment of these regions from B. burgdorferi strain 297 and the Pko isolate suggested that the P1 promoter sequences are conserved in strain 297 (data not shown). We also noted that the sequence of the extended −10 region of the P1 PospC (TGGACTAATAAT) is similar to the consensus for RpoSEc-dependent promoters [TGN0-2CTATA(C/A)T] (8, 24, 48, 49, 82), although the core −10 motif of PospC contains one more nucleotide than does the E. coli consensus sequence (Fig. 4). To explore the differences in the nucleotides or nucleotide motifs used by RpoSBb or RpoSEc to recognize and initiate transcription from RpoS-dependent promoters, we used mutagenesis to examine the interaction between each RpoS and PospC. For the first set of experiments, we substituted an A for T(−14) of PospC (PospCTA) (Fig. 4), based on the presumption that this nucleotide was analogous to T(−12) of the E. coli consensus promoter, which has been shown to interact directly with conserved residues within the 2.4 region of the σ70 family (86). Consistent with this supposition, the level of activity from PospCTA in the E. coli parent decreased to that observed in the rpoS mutant (Fig. 5). We also observed a significant reduction in activity from PospCTA in the wild-type clone of B. burgdorferi (Fig. 6). This level of fluorescence was still 10-fold higher than that in the B. burgdorferi rpoS mutant, however, suggesting that unlike RpoSEc, RpoSBb was still able to initiate significant levels of transcription from PospCTA (Fig. 6). To further demonstrate the difference in the abilities of RpoSEc and RpoSBb to recognize PospCTA, we introduced pACYC184(gfp)-PospCTA into LM5005 with pBAD, pBAD-rpoSBb, or pBAD-rpoSEc and analyzed promoter activity after arabinose induction. As we had observed in B. burgdorferi, the induced RpoSBb in E. coli also was able to recognize and transcribe PospCTA, whereas the induction of RpoSEc resulted in no higher level of activity than did pBAD alone (Fig. 7). Taken together, these results confirmed that the extended −10 region of PospC was involved in RpoS recognition in both B. burgdorferi and E. coli but that T(−14) was not as essential for RpoSBb-dependent transcriptional initiation as it was for RpoSEc.

FIG. 4.

A diagram of the B. burgdorferi strain 297 PospC. A small arrow indicates the approximate location of the P1 transcriptional start site identified by primer extension of the ospC gene of the B. afzeleii strain Pko (55). Nucleotide position numbering is with respect to the transcriptional start site (+1). Arrowheads designate the primer sites used in generating the full-length (PospC) and truncated (PospCtrunc) upstream regions. Bold-faced and underlined nucleotides indicate mutated positions within the −10 region. The E. coli extended −10 consensus sequence is shown in italics. The dotted-line arrows indicate the approximate positions of the inverted repeats relative to the transcriptional start site (not to scale).

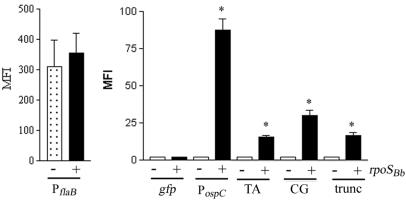

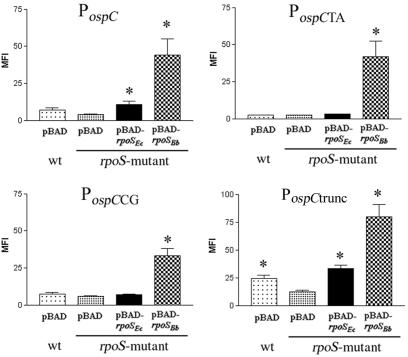

FIG. 5.

The RpoSEc recognition motif of PospC lies within a 65-bp core region. The activity levels of PospCTA (TA), PospCCG (CG), and PospCtrunc (trunc), and the full-length PospC, all cloned into pBS(gfp), were compared after 8 h of growth in either LM5005 (speckled bars) or MC4100 (solid bars). The level of expression from PflaB or gfp alone under the same conditions is shown for comparison. Asterisks indicate significant changes in the level of expression relative to that of the E. coli rpoS mutant transformed with the same fluorescent construct (P ≤ 0.01). Results shown are an average of ≥3 trials.

FIG. 6.

Mutations in PospC modulate activity in B. burgdorferi but do not affect RpoSBb dependence. Samples from 37°C cultures of c155 (+) and c174 (−) transformed with pCE320(gfp)-PospC, -PospCTA (TA), -PospCCG (CG), or -PospCtrunc (trunc), were stained with SYTO59 and analyzed for activity by flow cytometry. The level of expression from PflaB or promoterless gfp under the same conditions is shown for comparison. Asterisks indicate significant changes in the level of expression relative to that of the B. burgdorferi rpoS mutant transformed with the same fluorescent construct (P ≤ 0.01). Each graph represents an average of ≥3 trials.

FIG. 7.

The activity levels of PospCTA, PospCCG, and PospCtrunc in the presence of inducible RpoSBb or RpoSEc highlights differences between their recognition of RpoS-dependent promoters. The parent strain MC4100 with pBAD, or LM5005 containing the pBAD, pBAD-rpoSEc, or pBAD-rpoSBb vectors, was transformed with pACYC184(gfp)-PospC, -PospCTA, -PospCCG, or -PospCtrunc. Samples for analysis were collected 2 h after induction, and promoter activity was measured by flow cytometry. Asterisks indicate significant changes in the level of expression relative to that of the E. coli rpoS mutant transformed with both pBAD and the indicated fluorescent construct (P ≤ 0.01). Graphs represent an average of ≥3 trials.

Determining the role of C(−15) in RpoS selectivity of PospC.

Becker et al. (8) demonstrated that the nucleotide at position −13 of an E. coli promoter plays an important role in RpoS- or σ70-dependent gene expression, with RpoSEc favoring a C and σ70 favoring a G. To determine if C(−15) played an analogous role in the RpoSBb dependence of PospC, we mutated this nucleotide from C to G, generating PospCCG (Fig. 4). In E. coli, this promoter demonstrated a clear switch from RpoSEc to σ70 dependence, with levels of promoter activity observed in both the wild-type and rpoS mutant that were higher than those for native PospC (Fig. 5). In B. burgdorferi, however, PospCCG remained RpoSBb dependent, although with significantly less activity than the native promoter in the parental clone (Fig. 6). We also found that induced RpoSBb was able to significantly increase the amount of expression from the PospCCG promoter in the E. coli rpoS mutant (Fig. 7), demonstrating that the selectivity of RpoSBb for this promoter is stronger than that of E. coli σ70. In contrast, even induced levels of RpoSEc did not enhance expression from PospCCG. These results clearly indicated that the nucleotide at −15 of PospC does not play the same role in B. burgdorferi sigma factor selectivity as it does for E. coli.

Evaluating the role of the region upstream of the strong PospC promoter in RpoSBb recognition and initiation of transcription.

For a subset of RpoSEc-dependent promoters, sequences downstream of the −35 region play an important role in sigma factor selectivity and transcriptional initiation, either by interacting directly with a core subunit of RNAP or by providing binding sites for trans-acting regulatory factors (37). Carroll et al. (15) had previously demonstrated that a 179-bp PospC was sufficient for the temperature-dependent transcription of an ospC reporter but had not investigated the transcription levels from shorter promoter fragments. To determine if sequences upstream of the −35 region of the strain 297 PospC were required for temperature-dependent RpoSBb transcription, we generated PospCtrunc, which contained only the 65 bp upstream of the ospC translational start site (Fig. 4). When PospCtrunc was introduced into E. coli, we found that this promoter had activity levels equal to those of full-length PospC in the parental strain and that maximal expression was still RpoSEc dependent (Fig. 5). Furthermore, transcription from PospCtrunc was increased over that of the full-length promoter in the presence of either inducible RpoSBb or RpoSEc in the E. coli rpoS mutant (Fig. 7). When introduced into B. burgdorferi, however, PospCtrunc exhibited significantly less activity than the full-length PospC in the parental 297-c155 at 37°C, although the activity levels were still well above those observed in the RpoS mutant (Fig. 6). These findings suggested that the region upstream of the 65-bp “core” PospC is not essential for the temperature- and RpoSBb-dependent transcription of ospC but might contain an as-yet-unidentified B. burgdorferi-specific transcriptional enhancer element that is required for maximal expression of this gene.

DISCUSSION

A survey of the B. burgdorferi genome yields homologs to only three known transcription factors: σ70, RpoN, and RpoS (23). With this small number of sigma factors, B. burgdorferi must tightly coordinate the differential expression of the genes necessary for its physiological adaptation to, and maintenance within, two markedly different hosts. One of the keys to this coordination is likely to be the presence of specific promoter elements for determining sigma factor selectivity. In this report, we have used a combination of fluorescent transcriptional reporters and mutagenesis to compare and contrast RpoSBb-dependent transcription within B. burgdorferi and an E. coli surrogate with that of RpoSEc within E. coli. These studies have not only allowed us to begin dissecting the molecular determinants of the interaction between B. burgdorferi sigma factors and their dependent promoters, but they also have provided new insight into promoter recognition by sigma factors in general.

Because of the inherent complexities of conducting genetic studies with B. burgdorferi, the development of E. coli systems to augment the study of specific molecular and/or biochemical processes within the spirochete has been an attractive option for Lyme disease researchers (5, 50, 51, 66, 76, 87, 88). Furthermore, E. coli rpoS mutants have been used to identify RpoS orthologs from a number of organisms, including L. pneumophila (30), C. burnetii (73), and Pseudomonas putida (67). In this report, we have extended the use of such a surrogate not only to assess the ability of RpoSBb to complement an E. coli rpoS mutant but also to compare promoter recognition and transcriptional initiation by RpoSBb with that of the better-characterized RpoSEc. The availability of such a system will undoubtedly expedite future analyses of the interactions between RpoSBb and its dependent promoters within the Lyme disease spirochete.

Even though RpoSEc and RpoSBb share only limited overall sequence identity (28% identity, 20% similarity) (9, 23), the RpoSBb ortholog does contain a strong match to the most well-conserved region 2 domain, which includes both the −10 element recognition helix and the primary core RNA polymerase binding determinant (7, 14, 53) (data not shown). Based on the sequence homology of the RpoSBb and RpoSEc polypeptides, we predicted both that RpoSEc would be able to recognize RpoSBb-dependent promoters and that RpoSBb expressed in E. coli would form a functional holoenzyme. Indeed, these predictions were borne out by our findings with E. coli that RpoSEc was required for maximal expression of RpoSBb-dependent genes (Fig. 2) and that RpoSBb could initiate transcription from both RpoSEc- and RpoSBb-dependent promoters (Fig. 3). We did note, however, significantly higher levels of activity from either RpoSEc- or RpoSBb-dependent promoters in the presence of their cognate RpoS polypeptide compared to the levels in the presence of heterologous RpoS (Fig. 3). Based on these findings, we concluded not only that RpoSBb was able to interact with the other subunits of the E. coli RNAP holoenzyme but also that the presence of the heterologous subunit fundamentally altered the promoter recognition of the holoenzyme to reflect that of the B. burgdorferi sigma factor. In combination with our studies with B. burgdorferi, this surrogate system has allowed us to highlight key differences in the importance of certain nucleotides for RpoSBb and RpoSEc recognition and/or selectivity.

In addition to allowing us to compare the interactions between RpoSBb or RpoSEc and the extended −10 region of RpoSBb-dependent genes (discussed below), the use of this system also has given us insight into the possible importance of sequences upstream of PospC. We found that the region upstream of a core 65-bp promoter is necessary for maximal expression of the PospC transcriptional reporter in B. burgdorferi (Fig. 6) but not in E. coli with wild-type rpoS (Fig. 5), or in an E. coli rpoS mutant complemented in trans with RpoSEc or RpoSBb (Fig. 7). Although Marconi et al. (55) identified two very weak promoters upstream (P2 and P3) of the strong P1 PospC in B. afzelii strain Pko, these other promoter sequences are not conserved in B. burgdorferi strain 297 (data not shown). It seems likely that the reduction in activity from PospC observed in 297-c155 when the sequence upstream of the −35 element was truncated (Fig. 6) was a result of eliminating an as-yet-unidentified transcriptional enhancer(s) within this region. That a similar reduction in activity from PospCtrunc was not observed in E. coli (Fig. 5 and 7) furthermore suggested that any enhancer(s) eliminated by our truncation are likely B. burgdorferi specific. Based on our results, we might predict that this enhancement does not involve a direct interaction with the RpoSBb subunit but may, instead, stabilize B. burgdorferi RNAP holoenzyme-promoter interaction by providing either a cis element that directly interacts with a core subunit or a binding site for a trans-acting regulatory factor, such as one of the B. burgdorferi DNA-binding proteins (42, 43, 84). One notable feature of PospC is a pair of inverted repeats beginning approximately 75 bp upstream of the translational start site (23, 83; also data not shown) (Fig. 4), and Alverson et al. (5) have recently proposed that under increased levels of negative supercoiling, such as occurs at 23°C, these repeats could form an alternative secondary structure (i.e., a cruciform) that contributes to the repression of ospC. More work will be needed, however, to characterize what relationship, if any, exists between these inverted repeats and the enhancer(s) of ospC transcription at 37°C. Further investigation will also be required to determine if enhancer elements are found upstream of other RpoSBb-dependent genes or if this instead represents a specific layer of regulatory control for the differential expression of OspC.

While Hubner et al. (39) had previously established that the expression of OspC and DbpA was RpoSBb dependent, they did not examine whether this control was mediated by a direct interaction between the sigma factor and the promoters of these two genes. In our studies, the ability of an inducible RpoSBb to up-regulate expression from PospC, PdbpBA, and PospF in a heterologous E. coli surrogate (Fig. 3) argues in favor of such a direct interaction. In E. coli, the sequence determinants of RpoSEc selectivity for its dependent promoters seems to lie primarily within an extended −10 region (37). The core of this region consists of (i) a hexamer in which the most frequently conserved residues, T(−12), A(−11), and T(−7), are recognized by both RpoSEc and σ70 (21, 31, 48), and (ii) a C at position −13 that serves as a discriminator nucleotide for this sigma factor (8, 45) (Fig. 4). Our mutational analysis of PospC (Fig. 5 to 7) indicates that as with RpoSEc, the interaction of RpoSBb and this promoter also occurs through the extended −10 region, although the significance of certain nucleotides within this motif differs between B. burgdorferi and E. coli. In particular, we found that the substitution of an A for the nucleotide analogous to T(−12) weakens the interaction between RpoSBb and PospC (Fig. 6) but is not as critical for transcriptional initiation as is the corresponding nucleotide in E. coli promoters (Fig. 5 and 7). A previous study with E. coli (86) had found that members of the σ70 family had very low tolerance for an A at the analogous position in the −10 element of a σ70-like promoter. Our observation that RpoSBb can still recognize PospCTA suggests that the dynamics of promoter recognition and binding by RpoSBb may be different from that of RpoSEc. This idea was further supported by the finding that the C at the position analogous to −13 may be important for promoter recognition or binding of PospC but does not seem to have any role in RpoSBb or σ70 selectivity in B. burgdorferi (Fig. 6) as it did in E. coli (Fig. 5). This result was particularly interesting in light of the presence of a lysine at the position of the RpoSBb polypeptide that corresponds to K173 of the RpoSEc polypeptide (not shown). This residue in region 2.5 of RpoSEc has been shown to interact with the C(−13) in the E. coli RpoSEc-dependent promoter (8, 45). Taken together, these results suggest that the microenvironment at the site of RpoSBb-promoter interaction is likely very different from that of RpoSEc and its dependent promoters.

Important clues for eventually identifying determinants of sigma factor selectivity for a B. burgdorferi promoter may lie within the sequence differences of PospF and PospE. In B. burgdorferi, the evolutionarily (2, 13, 33, 56), and possibly functionally (4, 34, 44, 57, 58), distinct ospE and ospF genes are both transcriptionally up-regulated during tick engorgement and encode polypeptides that share a virtually identical lipoprotein signal sequence (2, 13, 17, 32, 33, 56, 79-81). Our analysis of gene expression in a B. burgdorferi rpoS mutant by using fluorescent reporters and immunoblotting has now provided important evidence that transcription from PospF in strain 297 is RpoS dependent, while that from PospE is not (Fig. 1). The 85 nucleotides upstream of the transcriptional start sites of the ospE and ospF genes differ by only 12 nucleotides (33). It seems likely that the determinants of RpoSBb selectivity for PospF are localized within these differences, all but one which is within, or downstream of, the predicted −35 region, with eight occurring between the extended −10 region and the transcriptional start site (33). The similarities of the −35 regions of PospE (TTGCAA) and PospF (TTGTAT) to each other and to the E. coli σ70 consensus sequence (TTGACA) further support the notion that, as for RpoSEc, promoter recognition and selectivity by RpoSBb is mainly mediated through interactions with the extended −10 region (reviewed in reference 37).

Of the three RpoSBb-dependent promoters that we examined with E. coli, the extended −10 sequence of PospF (TGCGTTAGACT) is the most dissimilar to that of the RpoSEc consensus sequence (Fig. 4). We were interested to find that RpoSEc was still able to recognize and initiate transcription from this promoter (Fig. 2 and 3C). This suggests that there may be as-yet-undefined elements of this promoter that interact with RpoSEc and that further study into this interaction may yield valuable insight into other recognition motifs utilized by this E. coli sigma factor. Unlike the case with B. burgdorferi (Fig. 1), another sigma factor also weakly recognizes PospF in E. coli. We presume that this other sigma factor is σ70, given both the σ70 dependence of PospE in B. burgdorferi and the similarities of the PospE and PospF promoters (33). That the E. coli σ70 also weakly recognizes PospF would suggest either that the recognition sequences for E. coli σ70 and RpoSEc overlap more than those for the B. burgdorferi sigma factors or that selectivity by the B. burgdorferi sigma factors for these two promoters is mediated by unknown motifs or factors that are not operative within the E. coli surrogate. The PospE and PospF promoters will be good candidates for future studies using the systems described in this report for increasing our general understanding of sigma factor recognition in both E. coli and B. burgdorferi and for identifying and characterizing the promoter elements that determine sigma factor selectivity in B. burgdorferi. Such studies will be critical for fully understanding the role that RpoSBb plays in the physiology, infection, transmission, and persistence of B. burgdorferi and in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Cynthia Gonzalez, Morgan LaVake, and André Dyer for technical assistance; Karsten Hazlett, Scott Samuels, and Xiaofeng Yang for useful discussions; and Scott Samuels and Karsten Hazlett for thoughtful and critical review of the manuscript. We thank Michael Norgard, Roberto Kolter, Howard Schuman, and Ferric Fang for providing strains and reagents.

Funding for this work was provided by grant AI-29735 from the Lyme disease program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (awarded to J.D.R. and M.J.C.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins, D. R., K. W. Bourell, M. J. Caimano, M. V. Norgard, and J. D. Radolf. 1998. A new animal model for studying Lyme disease spirochetes in a mammalian host-adapted state. J. Clin. Investig. 101:2240-2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akins, D. R., M. J. Caimano, X. Yang, F. Cerna, M. V. Norgard, and J. D. Radolf. 1999. Molecular and evolutionary analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi 297 circular plasmid-encoded lipoproteins with OspE- and OspF-like leader peptides. Infect. Immun. 67:1526-1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akins, D. R., S. F. Porcella, T. G. Popova, D. Shevchenko, S. I. Baker, M. Li, M. V. Norgard, and J. D. Radolf. 1995. Evidence for in vivo but not in vitro expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein F (OspF) homolog. Mol. Microbiol. 18:507-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alitalo, A., T. Meri, H. Lankinen, I. Seppala, P. Lahdenne, P. S. Hefty, D. Akins, and S. Meri. 2002. Complement inhibitor factor H binding to Lyme disease spirochetes is mediated by inducible expression of multiple plasmid-encoded outer surface protein E paralogs. J. Immunol. 169:3847-3853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alverson, J., S. F. Bundle, C. D. Sohaskey, M. C. Lybecker, and D. S. Samuels. 2003. Transcriptional regulation of the ospAB and ospC promoters from Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1665-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anguita, J., S. Samanta, B. Revilla, K. Suk, S. Das, S. W. Barthold, and E. Fikrig. 2000. Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression in vivo and spirochete pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 68:1222-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barne, K. A., J. A. Bown, S. J. Busby, and S. D. Minchin. 1997. Region 2.5 of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase σ70 subunit is responsible for the recognition of the ′extended-10′ motif at promoters. EMBO J. 16:4034-4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker, G., and R. Hengge-Aronis. 2001. What makes an Escherichia coli promoter σs dependent? Role of the −13/−14 nucleotide promoter positions and region 2.5 of σ s. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1153-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blattner, F. R. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohannon, D. E., N. Connell, J. Keener, A. Tormo, M. Espinosa-Urgel, M. M. Zambrano, and R. Kolter. 1991. Stationary-phase-inducible “gearbox” promoters: differential effects of katF mutations and role of sigma 70. J. Bacteriol. 173:4482-4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boylan, J. A., J. E. Posey, and F. C. Gherardini. 2003. Borrelia oxidative stress response regulator, BosR: a distinctive Zn-dependent transcriptional activator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:11684-11689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caimano, M. J., C. H. Eggers, K. R. O. Hazlett, and J. D. Radolf. RpoS is not central to the general stress response in Borrelia burgdorferi but does control expression of one or more central virulence determinants. Infect. Immun., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Caimano, M. J., X. Yang, T. G. Popova, M. L. Clawson, D. R. Akins, M. V. Norgard, and J. D. Radolf. 2000. Molecular and evolutionary characterization of the cp32/18 family of supercoiled plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi 297. Infect. Immun. 68:1574-1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell, E. A., O. Muzzin, M. Chlenov, J. L. Sun, C. A. Olson, O. Weinman, M. L. Trester-Zedlitz, and S. A. Darst. 2002. Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity σ subunit. Mol. Cell 9:527-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carroll, J. A., P. E. Stewart, P. Rosa, A. F. Elias, and C. F. Garon. 2003. An enhanced GFP reporter system to monitor gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology 149:1819-1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casjens, S., N. Palmer, R. van Vugt, W. M. Huang, B. Stevenson, P. Rosa, R. Lathigra, G. Sutton, J. Peterson, R. J. Dodson, D. Haft, E. Hickey, M. Gwinn, O. White, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 35:490-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casjens, S., R. van Vugt, K. Tilly, P. A. Rosa, and B. Stevenson. 1997. Homology throughout the multiple 32-kilobase circular plasmids present in Lyme disease spirochetes. J. Bacteriol. 179:217-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connell, N., Z. Han, F. Moreno, and R. Kolter. 1987. An E. coli promoter induced by the cessation of growth. Mol. Microbiol. 1:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobrikova, E. Y., J. Bugrysheva, and F. C. Cabello. 2001. Two independent transcriptional units control the complex and simultaneous expression of the bmp paralogous chromosomal gene family in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 39:370-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eggers, C. H., M. J. Caimano, M. L. Clawson, W. G. Miller, D. S. Samuels, and J. D. Radolf. 2002. Identification of loci critical for replication and compatibility of a Borrelia burgdorferi cp32 plasmid and use of a cp32-based shuttle vector for the expression of fluorescent reporters in the Lyme disease spirochaete. Mol. Microbiol. 43:281-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espinosa-Urgel, M., C. Chamizo, and A. Tormo. 1996. A consensus structure for sigma S-dependent promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 21:657-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fingerle, V., S. Rauser, B. Hammer, O. Kahl, C. Heimerl, U. Schulte-Spechtel, L. Gern, and B. Wilske. 2002. Dynamics of dissemination and outer surface protein expression of different European Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains in artificially infected Ixodes ricinus nymphs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1456-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraser, C. M., S. Casjens, W. M. Huang, G. G. Sutton, R. Clayton, R. Lathigra, O. White, K. A. Ketchum, R. Dodson, E. K. Hickey, M. Gwinn, B. Dougherty, J. F. Tomb, R. D. Fleischmann, D. Richardson, J. Peterson, A. R. Kerlavage, J. Quackenbush, S. Salzberg, M. Hanson, R. van Vugt, N. Palmer, M. D. Adams, J. Gocayne, J. Weidman, T. Utterback, L. Watthey, L. McDonald, P. Artiach, C. Bowman, S. Garland, C. Fujii, M. D. Cotton, K. Horst, K. Roberts, B. Hatch, H. O. Smith, and J. C. Venter. 1997. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390:580-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaal, T., W. Ross, S. T. Estrem, L. H. Nguyen, R. R. Burgess, and R. L. Gourse. 2001. Promoter recognition and discrimination by Eσs RNA polymerase. Mol. Microbiol. 42:939-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gattiker, A., E. Gasteiger, and A. Bairoch. 2002. ScanProsite: a reference implementation of a PROSITE scanning tool. Appl. Bioinformatics 1:107-108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ge, Y., I. G. Old, I. S. Girons, and N. W. Charon. 1997. The flgK motility operon of Borrelia burgdorferi is initiated by a σ70-like promoter. Microbiology 143:1681-1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ge, Y., I. G. Old, I. Saint Girons, and N. W. Charon. 1997. Molecular characterization of a large Borrelia burgdorferi motility operon which is initiated by a consensus σ70 promoter. J. Bacteriol. 179:2289-2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose pBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagman, K. E., P. Lahdenne, T. G. Popova, S. F. Porcella, D. R. Akins, J. D. Radolf, and M. V. Norgard. 1998. Decorin-binding protein of Borrelia burgdorferi is encoded within a two-gene operon and is protective in the murine model of Lyme borreliosis. Infect. Immun. 66:2674-2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hales, L. M., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. The Legionella pneumophila rpoS gene is required for growth within Acanthamoeba castellanii. J. Bacteriol. 181:4879-4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawley, D. K., and W. R. McClure. 1983. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:2237-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hefty, P. S., S. E. Jolliff, M. J. Caimano, S. K. Wikel, and D. R. Akins. 2002. Changes in temporal and spatial patterns of outer surface lipoprotein expression generate population heterogeneity and antigenic diversity in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 70:3468-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hefty, P. S., S. E. Jolliff, M. J. Caimano, S. K. Wikel, J. D. Radolf, and D. R. Akins. 2001. Regulation of OspE-related, OspF-related, and Elp lipoproteins of Borrelia burgdorferi strain 297 by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 69:3618-3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hellwage, J., T. Meri, T. Heikkila, A. Alitalo, J. Panelius, P. Lahdenne, I. J. Seppala, and S. Meri. 2001. The complement regulator factor H binds to the surface protein OspE of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8427-8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2000. The general stress response in Escherichia coli, p. 161-178. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 36.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Recent insights into the general stress response regulatory network in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:341-346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Stationary phase gene regulation: what makes an Escherichia coli promoter σs-selective? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:591-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2003. Regulation of gene expression during entry into stationary phase, p. 1497-1512. In E. M. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 39.Hubner, A., X. Yang, D. M. Nolen, T. G. Popova, F. C. Cabello, and M. V. Norgard. 2001. Expression of Borrelia burgdorferi OspC and DbpA is controlled by a RpoN-RpoS regulatory pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:12724-12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Indest, K. J., R. Ramamoorthy, and M. T. Philipp. 2000. Transcriptional regulation in spirochetes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:473-481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishihama, A. 2000. Functional modulation of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:499-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knight, S. W., and D. S. Samuels. 1999. Natural synthesis of a DNA-binding protein from the C-terminal domain of DNA gyrase A in Borrelia burgdorferi. EMBO J. 18:4875-4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobryn, K., D. Z. Naigamwalla, and G. Chaconas. 2000. Site-specific DNA binding and bending by the Borrelia burgdorferi Hbb protein. Mol. Microbiol. 37:145-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kraiczy, P., C. Skerka, M. Kirschfink, V. Brade, and P. F. Zipfel. 2001. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi by acquisition of human complement regulators FHL-1/reconectin and Factor H. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:1674-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lacour, S., A. Kolb, and P. Landini. 2003. Nucleotides from −16 to −12 determine specific promoter recognition by bacterial σS-RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 278:37160-37168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lane, R. S., J. Piesman, and W. Burgdorfer. 1991. Lyme borreliosis: relation of its causative agent to its vectors and hosts in North America and Europe. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 36:587-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lange, R., M. Barth, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1993. Complex transcriptional control of the sigma s-dependent stationary-phase-induced and osmotically regulated osmY (csi-5) gene suggests novel roles for Lrp, cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein-cAMP complex, and integration host factor in the stationary-phase response of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:7910-7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee, S. J., and J. D. Gralla. 2001. σ38 (rpoS) RNA polymerase promoter engagement via −10 region nucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 276:30064-30071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee, S. J., and J. D. Gralla. 2002. Promoter use by σ38 (rpoS) RNA polymerase: amino acid clusters for DNA binding and isomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47420-47427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin, B., S. A. Short, M. Eskildsen, M. S. Klempner, and L. T. Hu. 2001. Functional testing of putative oligopeptide permease (Opp) proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi: a complementation model in opp(−) Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1499:222-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liveris, D., V. Mulay, and I. Schwartz. 2004. Functional Properties of Borrelia burgdorferi recA. J. Bacteriol. 186:2275-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loewen, P. C., B. Hu, J. Strutinsky, and R. Sparling. 1998. Regulation in the rpoS regulon of Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:707-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lonetto, M., M. Gribskov, and C. A. Gross. 1992. The sigma 70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J. Bacteriol. 174:3843-3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Makinoshima, H., A. Nishimura, and A. Ishihama. 2002. Fractionation of Escherichia coli cell populations at different stages during growth transition to stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 43:269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marconi, R. T., D. S. Samuels, and C. F. Garon. 1993. Transcriptional analyses and mapping of the ospC gene in Lyme disease spirochetes. J. Bacteriol. 175:926-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marconi, R. T., S. Y. Sung, C. A. Norton Hughes, and J. A. Carlyon. 1996. Molecular and evolutionary analyses of a variable series of genes in Borrelia burgdorferi that are related to ospE and ospF, constitute a gene family, and share a common upstream homology box. J. Bacteriol. 178:5615-5626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDowell, J. V., J. Wolfgang, E. Tran, M. S. Metts, D. Hamilton, and R. T. Marconi. 2003. Comprehensive analysis of the factor H binding capabilities of Borrelia species associated with Lyme disease: delineation of two distinct classes of factor H binding proteins. Infect. Immun. 71:3597-3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Metts, M. S., J. V. McDowell, M. Theisen, P. R. Hansen, and R. T. Marconi. 2003. Analysis of the OspE determinants involved in binding of factor H and OspE-targeting antibodies elicited during Borrelia burgdorferi infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 71:3587-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. A laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria, p. 72-74. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 60.Miller, W. G., A. H. Bates, S. T. Horn, M. T. Brandle, M. R. Wachtel, and R. E. Mandrell. 2000. Detection on surfaces and in Caco-2 cells of Campylobacter jejuni cells transformed with new gfp, yfp, and cfp marker plasmids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5426-5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller, W. G., and S. E. Lindow. 1997. An improved GFP cloning cassette designed for prokaryotic transcriptional fusions. Gene 191:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morrissey, J. H. 1981. Silver stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels: a modified procedure with enhanced uniform sensitivity. Analyt. Biochem. 117:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ohnishi, J., J. Piesman, and A. M. Desilva. 2001. Antigenic and genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi populations transmitted by ticks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:670-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pal, U., and E. Fikrig. 2003. Adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the vector and vertebrate host. Microbes Infect. 5:659-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Porcella, S. F., C. A. Fitzpatrick, and J. L. Bono. 2000. Expression and immunological analysis of the plasmid-borne mlp genes of Borrelia burgdorferi B31. Infect. Immun. 68:4992-5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Putteet-Driver, A. D., J. Zhong, and A. G. Barbour. 2004. Transgenic expression of RecA of the spirochetes Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia hermsii in Escherichia coli revealed differences in DNA repair and recombination phenotypes. J. Bacteriol. 186:2266-2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ramos-Gonzalez, M. I., and S. Molin. 1998. Cloning, sequencing, and phenotypic characterization of the rpoS gene from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J. Bacteriol. 180:3421-3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roberts, D. M., M. Caimano, J. McDowell, M. Theisen, A. Holm, E. Orff, D. Nelson, S. Wikel, J. Radolf, and R. T. Marconi. 2002. Environmental regulation and differential production of members of the Bdr protein family of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 70:7033-7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Samuels, D. S. 1995. Electrotransformation of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Electrotransformation protocols for microorganisms. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:253-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schellhorn, H. E., J. P. Audia, L. I. Wei, and L. Chang. 1998. Identification of conserved, RpoS-dependent stationary-phase genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:6283-6291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schwan, T. G. 2003. Temporal regulation of outer surface proteins of the Lyme-disease spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:108-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwan, T. G., J. Piesman, W. T. Golde, M. C. Dolan, and P. A. Rosa. 1995. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2909-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seshadri, R., and J. E. Samuel. 2001. Characterization of a stress-induced alternate sigma factor, RpoS, of Coxiella burnetii and its expression during the development cycle. Infect. Immun. 69:4874-4883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seshu, J., and J. T. Skare. 2000. The many faces of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:463-472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Silhavy, T. J., M. L. Berman, and L. W. Enquist. 1984. Experiments with gene fusions, p. 107-112. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 76.Sohaskey, C. D., C. Arnold, and A. G. Barbour. 1997. Analysis of promoters in Borrelia burgdorferi by use of a transiently expressed reporter gene. J. Bacteriol. 179:6837-6842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sohaskey, C. D., W. R. Zuckert, and A. G. Barbour. 1999. The extended promoters for two outer membrane lipoprotein genes of Borrelia spp. uniquely include a T-rich region. Mol. Microbiol. 33:41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Steere, A. C. 2001. Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stevenson, B., J. L. Bono, T. G. Schwan, and P. A. Rosa. 1998. Borrelia burgdorferi Erp proteins are immunogenic in mammals infected by tick bite, and their synthesis is inducible in cultured bacteria. Infect. Immun. 66:2648-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stevenson, B., T. G. Schwan, and P. A. Rosa. 1995. Temperature-related differential expression of antigens in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 63:4535-4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stevenson, B., K. Tilly, and P. A. Rosa. 1996. A family of genes located on four separate 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 178:3508-3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tanaka, K., S. Kusano, N. Fujita, A. Ishihama, and H. Takahashi. 1995. Promoter determinants for Escherichia coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing sigma 38 (the rpoS gene product). Nucleic Acids Res. 23:827-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tilly, K., S. Casjens, B. Stevenson, J. L. Bono, D. S. Samuels, D. Hogan, and P. A. Rosa. 1997. The Borrelia burgdorferi circular plasmid cp26: conservation of plasmid structure and targeted inactivation of the ospC gene. Mol. Microbiol. 25:361-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tilly, K., J. Fuhrman, J. Campbell, and D. S. Samuels. 1996. Isolation of Borrelia burgdoreri genes encoding homologues of DNA-binding protein HU and ribosomal protein S20. Microbiology 142:2471-2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Volkert, M. R., L. I. Hajec, Z. Matijasevic, F. C. Fang, and R. Prince. 1994. Induction of the Escherichia coli aidB gene under oxygen-limiting conditions requires a functional rpoS (katF) gene. J. Bacteriol. 176:7638-7645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Waldburger, C., T. Gardella, R. Wong, and M. M. Susskind. 1990. Changes in conserved region 2 of Escherichia coli sigma 70 affecting promoter recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 215:267-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang, X. G., J. M. Kidder, J. P. Scagliotti, M. S. Klempner, R. Noring, and L. T. Hu. 2004. Analysis of differences in the functional properties of the substrate binding proteins of the Borrelia burgdorferi oligopeptide permease (Opp) operon. J. Bacteriol. 186:51-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang, X. G., B. Lin, J. M. Kidder, S. Telford, and L. T. Hu. 2002. Effects of environmental changes on expression of the oligopeptide permease (opp) genes of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 184:6198-6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang, X., M. S. Goldberg, T. G. Popova, G. B. Schoeler, S. K. Wikel, K. E. Hagman, and M. V. Norgard. 2000. Interdependence of environmental factors influencing reciprocal patterns of gene expression in virulent Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1470-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang, X. F., S. M. Alani, and M. V. Norgard. 2003. The response regulator Rrp2 is essential for the expression of major membrane lipoproteins in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1100-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]